This article examines the socio-historical significance of ‘Irish’ involvement in the British Empire Games (B.E.G.) of 1930, 1934 and 1938. J. A. Mangan has argued that during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sport was ‘an imperial umbilical cord’ and ‘a means of propagating imperial sentiments’.Footnote 1 One cultural expression of this was the British Empire Games movement. The inaugural games, held in Hamilton in 1930, were clearly incepted as a form of imperial glue and the choice of host reflected Canada's growing assertiveness in imperial affairs. But some of the athletes and national sports associations involved were also ‘ambivalent about imperialism’Footnote 2 and they grasped the opportunity to be recognised as separate teams. The more the British used sports generally, and the Empire Games particularly, to forge an imperial bond, the more the colonies and dominions also employed sport to foster their own sense of distinct identity and nationhood. Ireland was one of several other examples of dominion nationalism within the empire,Footnote 3 and played a key role in raising fundamental questions of representation and power in imperial relations.Footnote 4 As much as the Irish Free State sought to loosen imperial bonds and alter its status as a dominion within the empire,Footnote 5 Northern Ireland sought to cement its distinctive place within the United Kingdom, politically and sportively. Ulster unionists sought to project themselves as ‘more reliable subjects of the empire than the English’.Footnote 6 This struggle was played out in the context of sport when international sports bodies took differing views about the rights of athletes to be selected for Ireland, Britain or Northern Ireland.

Drawing on extensive archival, documentary and newspaper research across several countries, as well as family histories and interviews, we consider Ireland's limited but significant association with the games. Following partition and the establishment of Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State, a lesser known ‘Irish question’ emerged about governance and jurisdiction over athletics. International sports bodies, like the International Olympic Committee (I.O.C.) and the International Amateur Athletics Federation (I.A.A.F.), were clearly steered by British interests in the interwar period. In the course of disputes over the right of a national athletics association to govern on an all-island basis, several incidents can be isolated as significant, and served to shape future Irish involvement in athletics and other sporting arenas. Decisions taken in the 1930s about participation in the B.E.G. were foreshadowed by the Stormont government's refusal on political grounds to contribute to the costs of the 1928 all-Ireland Olympic team, and the issues over flag and anthem that arose on that occasion.

Questions were increasingly raised subsequently around who was represented at the British Empire Games and for what purposes; who was attracted to this representation and why (not); and how identities were imposed or embraced. This article thus also looks at the politics underpinning the selection of an all-island team for the first British Empire Games held in Hamilton (Ontario) in 1930. However, all-island sporting bodies at the 1934 London Empire Games were obliged to protest the restriction by the British hosts of their jurisdiction to the Irish Free State. In a confidential letter, the ‘Irish question’ was acknowledged as one of the greatest difficulties experienced by the British Empire Games Federation at the 1934 games.Footnote 7 Irish involvement in the Empire Games thus changed significantly over the decade in question.

A final key focus of this article is how political and ‘ordinary’ unionists actively evoked the propaganda value attached to sport. This was reflected in the claiming of medals won in 1934 by boxers, as well as in a reversal of the decision not to release members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (R.U.C.) to compete at the 1938 Sydney Games. During this ‘period of rituals’, unionist newspapers and the B.B.C. actively promoted the image and status of Northern Ireland and sought to make this synonymous with a six-county Ulster.Footnote 8 Unionists sought to grasp the soft power and propaganda utility of sport to forge a distinctive separate identity, and confirm the bond to empire, but without either placing themselves on the footing of a dominion or through disassociation from Britain.Footnote 9 Hitherto overlooked, the participation of a separate team from Northern Ireland in 1934 and 1938 lessened the insecurity felt there, and gave unionists a place within the U.K. and the empire. The examination that follows also strengthens analytical and interpretive accounts of the British Empire Games themselves.

I

The International Olympic Committee (I.O.C.) espoused the idea that Olympism would foster internationalism, yet nationalism became written into their rituals and ceremonies. In May 1936, a leading Hungarian sporting official wrote of this issue that the Olympic Charter ‘admits to represent a country in the Olympic Games acquired from the said nation or the sovereign state of which that nation is a part. Now a man from Ulster is no longer Irish and Ulster is a constituent part of the British Kingdom.’Footnote 10 This position on Irish jurisdiction differed from that first adopted by the I.O.C. on accepting Ireland's membership. After stalling a request for membership at two previous meetings, the I.O.C. had accepted John J. (J. J.) Keane, president of the Irish Olympic Council, as the member for Ireland in the early 1920s. As early as 1920, and in the following year, British Olympic officials Colonel Reginald Kentish and Reverend Robert de Courcy Laffan raised concerns at the I.O.C. about the situation in Ireland, including relations between the Irish Free State and what I.O.C. members mistakenly termed Ulster, and were successful in thwarting the claim of Ireland to membership. Kentish subsequently approved Keane's election ‘in the interest of peace as of sport’ in June 1922 after Keane had declared that the Irish Olympic Council was ‘open to all without any religious or ethnic distinction’.Footnote 11 Thus, Ireland was accepted into the I.O.C. on a thirty-two-county basis in which sport was regarded as above politics. The subsequent contested trajectory of the ‘Irish question’ lay in the imposition of the 1934 political boundary rule by international sportive bodies, acting on British efforts. Over the course of the twentieth century, this boundary rule inflected sportive relations for the worse, on a north-south and east-west basis, between Ireland and Great Britain, and international bodies, and between the various athletic bodies on the island. It also came to be embodied at an interpersonal level where relations between people involved in athletics were tense and even rancorous.

Olympic archives reveal that the movement's founder, Pierre de Coubertin, had reservations concerning the right to change the status of all-island jurisdiction ‘so radically’Footnote 12 — that is, from thirty-two to twenty-six-county jurisdiction. But, the imposition of the political boundary rule was supported by Count de Baillet-Latour (I.O.C. President who replaced de Coubertin) and British executive members, including Lord Aberdare, the British representative from 1931 to 1951. The rule in question was interpreted by some international sports officials to mean that athletes from Northern Ireland had become ‘English because of the creation of a new state’.Footnote 13 But, such interpretations were strongly contested by Irish Olympic and other sporting representatives, notably the (Irish) National Athletic and Cycling Association (N.A.C.A.), which was founded in the early 1920s and, like the Irish Olympic Council, was accepted into the international athletics federation on an all-island basis. Like many other divided/dividing societies, identity was thus both claimed and imposed in Ireland.

National field and track athletics championships were first organised in Trinity College Park in 1873.Footnote 14 Irish (male) athletes subsequently achieved notable international successes in the early modern Olympic games, winning twenty-five Olympic titles for Great Britain (officially the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland). The ‘Irish Whales’, a group of Irish-born athletes, also represented the United States and Canadian Olympic associations, and dominated the Olympic hammer throw and shot put events between 1896 and 1924.Footnote 15 Pat O'Callaghan won gold for Ireland in the hammer throw at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, saying on his return that: ‘I am glad of my victory, not of the victory itself, but for the fact that the world has been shown that Ireland has a flag, that Ireland has a national anthem, and in fact that we have a nationality.’Footnote 16

This was not the first case of Irish sportive nationalism on international athletics or Olympic stages. Harry Reynolds's complaint at the 1896 World Amateur Cycling Championships about the playing of ‘God Save the Queen’ and the flying of the Union Jack at his victory, and long- and triple-jumper Peter O'Connor's raising of an old Irish flag in 1906, were cases of Irish resistance to imperial rule.Footnote 17 Furthermore, national, political and cultural identities in Ireland were already entwined with questions concerning the organisation of sport on an all-Ireland basis, allegiance to national teams in international competition, and the right of Ireland to be represented in international sport, independent from Great Britain. Political leaders of the first unofficial Dáil met with the president of the Irish Olympic Council, Keane, in 1920 to seek international recognition for Ireland in the Olympic movement.Footnote 18 The Irish Olympic Council secretary also wrote to the secretary of the Dáil in June 1920, seeking its assistance from government officials based abroad ‘in obtaining independent recognition in athletics for “our nation”’.Footnote 19 The president of the Second Dáil, Éamon de Valera, and the Irish Ministers for Foreign Affairs (Arthur Griffith) and Finance (Michael Collins), approved funding for an ‘Irish Olympic Race’ meeting to be organised by James Joseph (J. J.) Walsh TD and held in 1922. Due to the War of Independence and Civil War, this meeting did not happen until 1924, when it was staged for ‘the organization, cohesion and solidarity of the Gaelic Race at home, and in particular abroad’.Footnote 20 In late 1922, the N.A.C.A. was formed from a merger of three other athletics bodies. Some two years later, a separate athletic and cycling group formed for Northern Ireland. This northern group became ‘masters of [their] own household, having [their] own local autonomy’Footnote 21 and affiliated to the (English) Amateur Athletic Association, becoming the Northern Ireland A.A.A. (N.I.A.A.A.) in late 1930.

Several unsuccessful attempts were made in the late 1920s to reintegrate the northern group into the all-island body. Relations between them in this period were generally pragmatic, if sometimes strained, but could become overtly protectionist and hostile as the ideological mortar hardened between them. Continual accusations were made by both sides that in asserting claims to jurisdiction each was bringing politics into sport. But politicians on the island were already actively involved in using sport for non-sportive ends — namely, the symbolism of sportive representation on the international stage as a means of projecting identity and/or asserting a right to independence.

Such jurisdictional and eligibility claims were part of a much greater political, diplomatic and cultural drama. First, what might be termed ‘British questions’ arose regarding how to recognise those in Northern Ireland who held greater affiliation to Great Britain in sport, and concerning the new Irish Free State and its claims to nationality and citizenship. ‘Irish questions’ arose about how to resolve internal tensions — sporting and political. Meanwhile, for the international athletic and Olympic worlds, questions emerged concerning claims to jurisdiction beyond political boundaries that challenged their preferred interpretation of ‘country’. In the international Olympic and athletics movements, the British view dominated on the primacy of British over Irish citizenship and national identity in the period under examination. Moreover, the actions of Stormont ministers affirmed that athletics was a means of promoting a separate identity and jurisdiction, thereby ensuring unionist political and sportive hegemony. During this period, the N.A.C.A. and the Irish Olympic Council could, and did, lay continued claim to thirty-two-county jurisdiction.

II

Ulster unionist control of the Northern Irish parliament was a safeguard against official unionism's enemies, internal and external.Footnote 22 The parliament was dominated by two influential ministers: Sir James Craig (who became Lord Craigavon in 1927) and Sir Richard Dawson Bates. Along with Thomas Moles, M.P. for Belfast South, who combined roles as Stormont speaker, managing editor of the Belfast Telegraph and President of the N.I.A.A.A., the trio engaged sports in the political advancement of the newly created Northern Ireland.Footnote 23 Their actions furthered the right of the N.I.A.A.A. to govern athletics in the six counties and, in so doing, hardened sportive partition. As noted above, a northern athletics group informally split from the all-Ireland body in July 1925, and they achieved recognition from the A.A.A. as an affiliate in 1930. However, many other sports retained all-Ireland jurisdiction.

Prompted by Moles and Dawson Bates, and supported by the finance minister, Hugh Pollock, and others in the fledgling Stormont civil service, the Northern Ireland government intervened directly in the question of athletic jurisdiction in the late 1920s. This was in response to a request from the Irish Olympic Council for funding towards the cost of sending an all-island team to the 1928 Olympics. Athletics, boxing and swimming were Olympic sports, and representatives of each were central to the formation of the Irish Olympic Council. There was ‘No thought of forming it on a territorial basis as between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland arose’.Footnote 24

Following a letter from Comdt John Chisholm, secretary of the Irish Olympic Council (and Irish national army), to Pollock in January 1928, Pollock's secretary, W. Duggan, wrote to the Irish Department of Finance, enquiring about their attitude towards funding the costs of sending an Olympic team. Robert Rowlette, an Irish Olympic Council member, personally assured Duggan that Ireland was ‘one country, and the teams in the different branches of sport will be representative of both north and south’. Rowlette also felt that if Pollock were to consider the request for a grant favourably, it would be reasonable for the Stormont Minister to nominate members to the council.

On 27 January 1928, Chisholm duly confirmed to the Stormont Ministry of Finance that the Irish Olympic Council was representative ‘of all Ireland without distinction or reservation’, and that two positions on their executive committee had been reserved for members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, which had active athletics and boxing associations, the R.U.C. Athletics Association having been formed in 1928 by Captain T. D. Morrison. This letter stated that the national all-island athletics, boxing and swimming associations were ‘the only Irish associations affiliated to, and recognized by kindred associations in England, Scotland, Wales and the other countries of the world’.Footnote 25 On 13 February 1928, Duggan noted in his own handwriting that Pollock ‘did not appear very sympathetic’ and, elsewhere in the same letter, an unidentified official in Finance at Stormont wrote that there were some grounds for help as long as the ‘flavour wouldn't be wholly green and gold’. Duggan wrote a personal reply to Rowlette on the same day, identifying two points of difficulty: the first was the growing tension between the (breakaway) northern athletics body and the all-island N.A.C.A. which had ramifications for the question of Royal Ulster Constabulary representation on the Irish Olympic Council. The R.U.C.'s Inspector General was ‘marking time in the hope that the two associations [would] compose their differences in view of the impending Olympic sports’. The second (political) point was whether and how the idea of there being two governments on the island would be conveyed if the team was ‘required to drape themselves in the Free State flag or otherwise parade themselves in such a way as to give the idea … that there is only one government in Ireland’.Footnote 26

Later that month, Rowlette, in his reply to Duggan, was (wrongly) of the view that the breakaway Northern Irish athletics body (then chaired by Moles) would not obtain recognition from England and Scotland. On the question of a team flag, he suggested that many members of the Irish Olympic Council would agree to a representative all-Ireland flag. Rowlette's various personal assurances were not matched in Duggan's official assessment, however. Duggan rightly predicted the potential for the Irish team to become an outlet for ‘European propaganda on behalf of the Free State’ and the claim for all-island sovereignty. Thus, Duggan recommended to Pollock that as a condition of any Northern Ireland grant, the Irish Olympic team be representative of ‘Protestant British interests’ by requiring that the Union Jack be flown in the procession of athletes and with the emblem of the shamrock badge. Moles and Pollock concluded that no useful purpose would be served either by seeing a deputation from the Irish Olympic Council in Belfast or making financial aid available to them. This decision was communicated to the Irish Olympic Council on 5 March 1928. A little over a year later, Northern Irish politicians intervened with the English A.A.A. and British members of the international Olympic and athletics movements to secure the official sanctioned right of the N.I.A.A.A. to govern athletics in the six counties and be affiliated to British (not Irish) sport.Footnote 27

In May 1929, Dawson Bates wrote to the A.A.A. concerning the jurisdiction of the Northern Ireland athletics group. Separately, he also wrote to the R.U.C. concerning any association with the playing of the Soldier's Song (Amhrán na bhFiann) or the display of Free State emblems at sporting events. He claimed that the Northern Irish athletic association had for some years endeavoured to affiliate to the A.A.A. but that what he incorrectly termed the Irish Free State association had put obstacles in the way, and had ‘used as an argument the fact that Northern Ireland is part of the Irish Free State’. He also raised the question of the risk of possible suspension by the N.A.C.A. of any R.U.C. members involved in events held under Northern Ireland auspices. No evidence was supplied as to these issues. He also pointed out that members of the military forces stationed in Ireland were debarred from events held under the auspices of the Northern Ireland association.Footnote 28

Pollock also urged the A.A.A. to act on behalf of the Northern Ireland athletics group seeking affiliation. Stephen Williamson, sub-editor of the Belfast Telegraph, wrote to him about the issue of R.U.C. involvement with N.A.C.A. athletic events and said, ‘it is really too bad that a body of men under Ulster government auspices and paid by Six County ratepayers should thus openly proclaim their sympathies with a Dublin organization whose flag for Olympic Games purposes is the Tricolour and marching air “The Soldier's Song”’.Footnote 29 Williamson acknowledged that the minister responsible for the R.U.C. was the home secretary, but he was then communicating with Pollock in his role as acting prime minister. It appears that Williamson and Moles coordinated their efforts because a handwritten note from Moles to Pollock on 22 January 1930, also on Belfast Telegraph headed paper, included an annotated draft of the letter that was subsequently sent by Pollock, in his role as acting prime minister, to the A.A.A. Pollock was also urged by Dawson Bates to act in this way.Footnote 30 A month later, a copy of the attorney general's notes on legal jurisdiction was forwarded to the Stormont Ministry of Home Affairs. For Dawson Bates, there were now two athletic associations of comparable status on either side of the border. For others however, such as Charles Wickham, R.U.C. inspector general, the northern athletics group had constituted themselves before receiving any recognised status, they had tried to induce other clubs (such as the R.U.C. Athletics Association) to affiliate to them because of their weaker representation and he did not think that ‘the North would wish to sink its identity into the English team’.Footnote 31 Nevertheless, Sir James Craig pressed the case personally with Lord Desborough, British Olympic chairman and executive member of the I.O.C.,Footnote 32 to ensure the N.I.A.A.A. obtained British affiliate status. In this way, the case for separate athletic (and sportive) jurisdiction was pressed by leading unionist government politicians through official channels to British counterparts and onwards to international sports bodies. This sportcraft triggered a series of events in Britain, involving consultation with the Dominions Office, and that led to the production of a memo which favoured the claims of the Northern Ireland athletics association. It asserted that ‘when a new unit is created by political action, the authorities in that new unit are entitled to apply for membership of the I.A.A.F.’Footnote 33

This heightened ideological climate surrounding sportive jurisdiction, eligibility for national team selection and nationality was also manifest elsewhere. For example, the Finns used the 1908 Olympic Games to claim an independent nationality.Footnote 34 But in Northern Ireland, and the nine-county province of Ulster more broadly, the situation was even more knotty because of the forcible creation of a double minority. Not only was there a smaller population of Irish nationalists relative to the unionist majority but there were also sportive unionist enclaves in Ulster. Some of these were in individual athletic and cycling clubsFootnote 35 who felt that recognition by, and affiliation with, their British/English counterparts was preferable to all-island Irish bodies politically and sportively. The interests and actions of these sportive unionist enclaves in athletics generated more impetus for autonomy, separate from the N.A.C.A. The N.A.C.A. regarded these separatist moves as having been orchestrated by British athletic and cycling groups, who they believed sought to intervene in their jurisdiction. Moles's prominence in athletics assured political support for a separate athletics association, thus ensuring that the emerging ideological split over national identity and jurisdiction between ‘northern’ and ‘southern’ athletics became deeper and more enduring (and remains so today). In this way, articulations of sportive nationalism on the island used the same symbolic devices, of anthem, emblem and flag, but did so to express different identities. These competing sportive nationalisms would also find expression in the 1930s in the British Empire Games.

III

Ireland (via the N.A.C.A.) selected and sent an all-island team to the inaugural games, held in 1930. No evidence has yet been located to confirm whether this all-island selection, and the team's name — Ireland — was formally agreed with representatives of the breakaway northern body or if they were even consulted about this by the N.A.C.A., the A.A.A. or the organisers of the games. Some unionist newspapers claimed that the northern association was invited separately.Footnote 36 Scottish papers reported that Melville (Bobby) Robinson, Canadian representative of the 1930 organising committee, had addressed meetings in England and Ireland.Footnote 37 It was also reported that Irish Free State officials had told Robinson that they would be prepared to unite with Northern Ireland to send an Irish team, and that sporting officials in Northern Ireland had said they would meet their Free State colleagues on a joint team proposition, failing which they would consider sending their own team.Footnote 38

Even so, there were doubts about the participation of a team from Ireland. The N.A.C.A. were in a double bind owing to nationalist sensitivities and the changing face of international sport.Footnote 39 On 5 April 1930, the A.A.A. passed a resolution that the territory under N.A.C.A. jurisdiction extended to the Irish Free State only, thereby delegating to the N.I.A.A.A. full powers to control amateur athletics there.Footnote 40 Meanwhile, the N.A.C.A.'s central council debated at length the invitation to take part in the games.Footnote 41 Some in the N.A.C.A. did not want to send a team to the Empire Games because that would create further athletic discord ‘as a political significance might be attached’.Footnote 42 Others maintained the illusion that sport and politics did not mix at all. More in the N.A.C.A. saw participation in the games as an opportunity to brand Ireland on the empire stage, saying ‘it would be for the good of the country [emphasis added] … to send out … athletic ambassadors to these countries’, the ‘team would represent Ireland … if [they] did not receive such an assurance, then [they] might not send one’.Footnote 43 The assurance being sought was that the team name would be Ireland — in this demand they succeeded. A few others in the N.A.C.A., including Rowlette who (earlier) lobbied Stormont for funding for the Irish Olympic team, argued that they ‘should have nothing to do with any part of the British Empire’.Footnote 44 Following a vote — eight to four — it was agreed to send a team on condition of separate representation for Ireland.

During the build-up to the 1930 games (March to July), national and international developments overlapped and that reflected a burgeoning globalisation of sport. These developments included a visit to London by the aforementioned Melville Robinson to rally support for the games, the formal imposition of restricted twenty-six-county jurisdictional status for the N.A.C.A. by international athletics and the affiliation of the N.I.A.A.A. with the (English) A.A.A. Yet, the N.A.C.A. was intent on the selection of a thirty-two-county British Empire Games team, as was the Irish Amateur Swimming Association (I.A.S.A.) when they were invited to the second British Empire Games four years later.

Identity politics were brought to life at the British Empire Games through the elements of anthem (‘God Save the King’), oath of allegiance to imperial rule, and emblems and flags (imperial and national). The oath, which was read aloud by one athlete at the opening ceremony on behalf of all competitors, said: ‘We declare that we are all loyal subjects of His Majesty the King Emperor, and will take part in the British Empire Games in the spirit of true sportsmanship, recognizing the rules which govern them and desirous of participating in them for the honour of our Empire and for the glory of sport.’Footnote 45 ‘Rule Britannia’ was also sung as teams retired from the opening parade.Footnote 46 These sporting rituals around citizenship and pageantry reinforced the imperial ethos.Footnote 47 The British Empire Games enabled competitors and spectators to portray their varied national and imperial ideals. But the Irish case had ramifications for understanding the growing nexus of state formation and sportcraft.

IV

By the 1920s, the British Empire was experiencing increasing strain across the globe. Several internal and external conflicting processes were at work. Countries such as Australia and Canada were seeking to establish their own independent status. The U.S.A. had also grown to such a degree as to pose a challenge to, and perhaps surpass, the empire, whose future then was less certain. Successive British governments sought various economic, political and cultural responses to these ongoing tensions. Two were the move to ‘imperial preference’ and the notion of a common citizenship across the empire.Footnote 48 The former was a mutual tariff reduction between members of the empire and the latter reflected the case pressed by dominions for expanded imperial citizenship rights for their constituents. Political leaders in London and across the Dominions recognised that stronger cultural bonds were needed to hold the empire together.Footnote 49 Sport was viewed as one means of achieving this.

Some in the executive of the Olympic movement (such as President de Baillet-Latour) regarded the Empire Games initially as calculated to challenge the success of the Olympics,Footnote 50 but diplomatic assurances were received from Canadian athletic and Olympic representatives.Footnote 51 Canada was chosen to host the inaugural Empire Games because they were holders of the Lonsdale Cup, ‘the symbol of Empire athletic supremacy’,Footnote 52 which was first presented at the Festival of Empire in 1911 that celebrated the coronation of King George V. Their diplomatic efforts to boost the event included a visit by a Canadian organising representative, Bobby Robinson, to London in May 1930. Robinson was also a well-known Olympic official. Also included in the organising committee were Hamilton city residents, and industrial and municipal leaders, such as the president of Canadian Pacific Railway and the city mayor.Footnote 53 This committee embodied English Canada's imperial connection and capitalised on the ‘pan-Britannic movement’ of the late nineteenth century whose proponents advocated periodic festivals to celebrate imperial relations and the athletic prowess of the ‘Anglo-Saxon race’.Footnote 54

But, given his Olympic experiences in 1928, where he was enraged about the perceived lack of respect shown to the Canadian team by some nationalistic German and American athletes and officials, Robinson was also motivated by a desire to promote friendlier relations between teams as a counterpoint to the growing competitiveness of the Olympic movement.Footnote 55 Thus, the moniker of the ‘friendly games’ was born. In London, he pressed the A.A.A.'s general committee to ensure the participation of the ‘motherland’. Based on a report in the Belfast Telegraph in May 1930, at their congress meeting in Berlin, the I.O.C. were also concerned that ‘England’ would ‘break away from the Olympic Games and devote herself to the development of British Empire Games’ because of the British desire to protect the amateur status of sport.Footnote 56

In this way, the Canadian hosts overcame suspicions from within international sport and the empire and, in so doing, attracted ten other dominion/empire teams to Hamilton. The principle of independent representation by a national teamFootnote 57 was a central issue for the N.A.C.A. On that condition, they responded favourably to the invitation from the Canadian hosts who also wanted a separate Scottish team.Footnote 58 The Irish Amateur Boxing Association declined the invitation, claiming that they were focussed on preparation for the 1932 Olympics.Footnote 59

Five Irish athletes — not three as is claimed in another sourceFootnote 60 — travelled to compete in athletics under the team title of Ireland: four on the track and one in field athletics. All were members of the N.A.C.A., including one from Belfast. The N.A.C.A. Council explored the selection of a team comprised of more than five representatives, but the timing of the International University Games in Darmstadt, Germany, from August 1–10, prevented those who competed there from travelling to Hamilton in sufficient time. Birth qualification criteria adopted by the B.E.G. organisers also ruled out those who did not possess an Irish passport.Footnote 61 Though the pro-unionist Belfast News Letter and the Northern Whig reported that the Hamilton organisers had been in touch with governing bodies in Northern Ireland and what they termed the Irish Free State,Footnote 62 and that ‘encouraging responses’ had been received from ‘many parts of the Empire, including Northern Ireland’, no official correspondence has been located to confirm whether a separate invitation was issued to the N.I.A.A.A. Connections to Northern Ireland were celebrated in local newspapers, such as the Ballymoney Free Press, which noted that ‘Jimmy’ Gordon (son of a local man, William Gordon) was ‘making a name for himself’ at the Canadian British Empire Games boxing trials.Footnote 63 But, the Irish team was all-island in composition. The Belfast Telegraph covered the opening day of these games on 15 August 1930, describing ‘a sporting spectacle which will go down in history as the Empire's first Olympiad’. ‘Eleven units of Empire’ sent teams, it said, that included ‘Ireland’ and ‘the Motherland’.Footnote 64 Bill Britton won silver for Ireland in the hammer throw event. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Britton was Aonach Tailteann winner and a leading field athlete. He also represented Ireland and Great Britain in invitational events, including bi-annual meets between the Empire and the USA (see figure 1).Footnote 65

Figure 1. Bill Britton's dual athletic representation

Credit: Britton family collection

Figure 2. 1930 Medal podium for hammer throw

Credit: Hamilton Public Library, Record 32022189115450

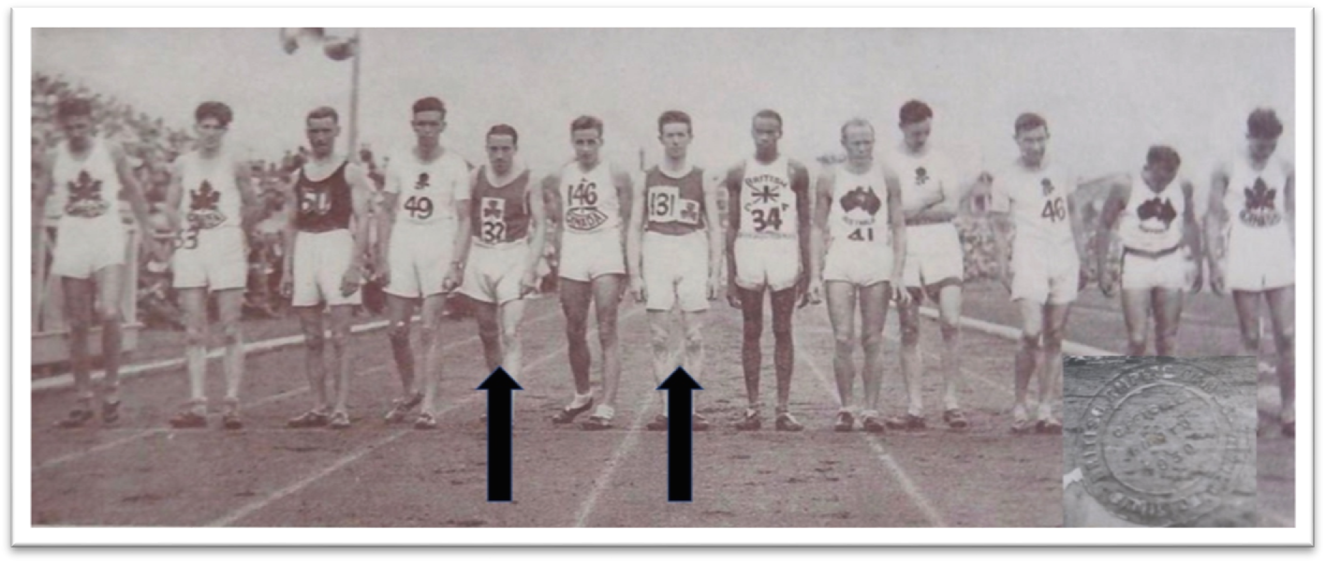

Four athletes represented Ireland on the track in 1930. Newspapers claimed that Mick O'Malley and Bill Dickson (North Belfast Harriers) missed their events due to the fog-delayed arrival of the team. O'Malley was listed (retrospectively and incorrectly) by a provincial Irish newspaper, the Western People, as a member of the British team, while Ireland's Saturday Night reported that Welsh and what they termed Free State representatives were detained by fog and, as a result, Eustace missed the 220 yards and Dickson and O'Malley the half mile.Footnote 66 B.E.G. historical records indicate that this claim was incorrect. Dickson's selection represented the N.A.C.A.'s continued all-island claim in the face of imposed restriction of their jurisdiction, as well as the agency exhibited by athletes from the north who sought to keep politics out of sport. Folklore within the N.I. Commonwealth Games Council today (gleaned via an interview with a leading official) suggested that Dickson may have deliberately missed an event for political reasons, because he was uncomfortable or disagreed with thirty-two-county Irish representation. However, an official stamped original photo of the 1930 B.E.G. (figure 3) was uncovered in a family collection, showing that O'Malley and Dickson started in the same qualifying round of the one-mile run. However, it is unclear whether one or both finished the race. A nephew of O'Malley recalled a family claim that ‘Mick was treated very badly because of the Games by the N.A.C.A.’ but he had not probed this further.Footnote 67

Figure 3. 1930 B.E.G. one-mile start showing O'Malley and Dickson.

Credit: O'Malley family collection

It does appear from B.E.G. historical records that Joe Eustace was late for another of his events. The fourth Irish track athlete, Jack O'Reilly, an emigrant living in Canada, wrote to the N.A.C.A. stating his availability for the marathon if selected. O'Reilly was winner of the Dublin–Navan marathon and medallist in the U.S. and Canada.Footnote 68 It is likely that he was the sole Irish representative pictured in film footage of the opening ceremony (see figure 4).Footnote 69 Reflecting the complexities of ‘Irishness’, a County Down runner, Sam Ferris, won silver for England in the same marathon event. He was in the Royal Air Force stationed in England and registered with an English athletics club. Ferris had previously represented Ireland in cross country running (1925–7) and earned silver for Great Britain at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. Ferris's medal was reported by the Belfast Telegraph under the headline ‘Free State Defeats’. These defeats referred to Eustace who placed third in his 100 yards heat, Britton's silver medal and Reilly.Footnote 70 All three were listed in the newspaper as representing the Irish Free State.

Figure 4. Ireland at 1930 opening ceremony

Credit: Still from 1930 Empire Games Film Footage, V1 8502-0086, Canadian National Archives

The complexity of Irish-imperial relations was reflected in protests, from within and outside the N.A.C.A., about the 1930 Ireland team. The president of the G.A.A., Sean O'Ryan, published an objection, as did the Cork County Board of the G.A.A.Footnote 71 Neither wished to be associated with empire, reflecting a strong nationalist ethos in Munster that prevailed throughout the N.A.C.A.'s prolonged struggle for all-island recognition during the twentieth century. The decision of the N.A.C.A. to send a team to Hamilton led to the voluntary disbandment of one of their clubs, Croke A.C., located in Dublin, who ‘viewed with deep concern the seriousness of any association claiming to be national participating in British Empire projects by consent, as it has no precedent in our long and trying history’.Footnote 72 On 15 August, the same newspaper also explained that the Dublin club had disbanded because their member, J. B. Eustace, was selected on the Irish team.

In discussions between the athletics bodies on the island of Ireland concerning an all-island team and a unified sports body, some common ground had been paved for the adoption of the old Irish flag — a golden harp on a blue background. This was the flag of azure or sky blue, also known as St Patrick's Blue, and worn by the team of the Irish Football Association (Belfast) from 1882 until 1931, and by the Football Association of Ireland Free State team as their change strip at the 1924 Olympics. This flag was adopted by the Irish B.E.G. team in 1930, though it is yet unclear whether the harp was displayed on a green or blue background.

At the conclusion of these games, standards were presented to each of the teams, including Ireland, for whom it appears Britton was the nominated captain/manager owing to his medal success.Footnote 73 These standards were to be ‘taken home (and) to be preserved until the next games’Footnote 74 in 1934, but it is unclear whether this happened given the increasing animosity between the N.A.C.A. and N.I.A.A.A. In any case, the Dublin government began to assert its preference for the use of the tricolour flag and the choice of Irish national anthem at international sporting events, such as rugby matches, and at other official functions abroad.Footnote 75

In the period between the first and second games, an international athletics commission was established, presided over by Swedish Consul General to Britain, Emil Sahlin, to adjudicate on the question of all-island jurisdiction. A seven-hour meeting was held in London in November 1931. Various accounts of this (from Irish and British perspectives) suggested that the A.A.A. would not object to Ireland competing as one geographical unit at the 1932 Olympics and that a genuine desire existed to permanently end the dispute. Yet, the A.A.A. and the British Olympic Association (B.O.A.) retained a durable interest in sporting jurisdiction on the island, going on to lay claim, unsuccessfully, to a G.B. and N.I. 1932 Olympic team. Discussions continued between the two Irish athletic associations and, by February 1932, the question of national flag was the principal sticking point in attempts at athletic unity between them. Agreement was reached on a flag that would show the arms of the four provinces on a field of St Patrick's Blue, but at their annual congress in April 1932, N.A.C.A. delegates insisted that the tricolour be used for all international events. This change of preference was unacceptable to several Belfast-based athletic clubs (Ulsterville, North Belfast, Duncairn Nomads, Albertville, 9th Old Boys and Queen's University) who seceded from the N.A.C.A.'s provincial council in Ulster and affiliated to the N.I.A.A.A.Footnote 76 This hardened the sportive boundary, in ideological and jurisdictional terms.

The N.A.C.A.'s February 1934 congress voted to reject the I.A.A.F.'s political boundary rule, by twenty-seven votes to twenty-four. This congress was attended by P. J. O'Keefe, secretary of the G.A.A., who was quoted as saying ‘the G.A.A. had the same interest in athletics today as they had forty-nine years ago when the Association was first formed, primarily for the development of athletics in Ireland’.Footnote 77 At this congress, Pat O'Callaghan (representing Cork) also stated that while Ireland had secured the majority of support at the Los Angeles meeting of the I.O.C. in 1932 on the matter of all-island jurisdiction, one English delegate had remarked to him then that ‘we will get you in committee’.Footnote 78

The question of jurisdiction in Northern Ireland was subsequently tabled at the 1934 I.A.A.F. congress held in Stockholm on 28–29 August. There, after ten abstentions, a vote of nine to one supported the formation of the International (British) Board of the A.A.A., including Northern Ireland. President Sigfrid Edström, who had as early as 1920 sided with the British to prevent Ireland's application for I.O.C. membership, pushed for a vote on the I.A.A.F. council's interpretation of rule one (political boundary), which was passed by twelve votes to none, and in which seven members abstained. No documentation is available (yet) that explains these abstentions. In their 1946 pamphlet, Partition in Irish athletics, the N.A.C.A. claimed that ‘the main purpose of the Council in asking the I.A.A.F. Congress to sanction an interpretation of a longstanding rule, and passing a bye-law to define same, was to nullify the appeal of the N.A.C.A.(I) against the Council's ‘26 Counties decision and to justify and make legal that decision which would otherwise have been ultra vires’.Footnote 79

Just weeks before this, between 4–10 August, the second British Empire Games had taken place in London. There, the question of all-island representation became much more contentious than in Hamilton, owing to the hardening of ideological, political and sportive boundaries on the island in the ensuing period. But, an added dimension was the influence of the British hosts of these games. They imposed their views of restricted sportive jurisdiction on all-island bodies. In these ways, what British and international sport officials termed the ‘Irish question’ became more contentious and it also drew the attention of the wider Northern Ireland public by virtue of patriotic newspaper coverage given to British hosting of an international Empire sports event.

V

1934 official reports list sixteen members of an Irish team among 500 competitors. The treatment of entries from the island of Ireland by the hosts carried much symbolic weight, in terms of who was permitted to compete and for what recognised team — the Irish Free State, Northern Ireland or Ireland. The approach adopted by the British also had consequences for the organisation of later empire games. Being the host, and the ‘motherland’, gave the British scope to impose their preferred views on eligibility and jurisdiction in/on Northern Ireland. In his personal reflections on the 1934 games contained in confidential advice to James Eve for the 1938 games, Evan Hunter, secretary of the British Empire Games Federation (B.E.G.F.), said that the Irish question ‘wants very careful handling … The great difficulty [was] that some of the sporting associations cover[ed] the whole of Ireland and were unwilling to split their forces.’Footnote 80

By 1934, Lord Lonsdale was the B.E.G.F. president and Lord Burghley (who showed himself hostile to the quest for all-island recognition for decades subsequently) was joint treasurer.Footnote 81 The formation of this federation was first discussed in 1930 and again at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics,Footnote 82 and ‘Subsequently most of the dominions having formed their own national councils, a meeting was held in London and the parent federation was formed.’Footnote 83 N.I.A.A.A. minutes show that they had cemented their official status by 1934, thus claiming jurisdiction over athletics in the six counties and affiliation to the British Amateur Athletics Board. The chair of the B.E.G.F., Sir James Leigh Wood, wrote to the N.I.A.A.A. in January, inviting them to nominate a team.Footnote 84 This invitation to ‘a Northern Ireland team’ was also reported in the Belfast Telegraph one day later and in its weekend sports paper, Ireland's Saturday Night, that ran separate editions for the north and south.Footnote 85 But, there was disagreement within the N.I.A.A.A. as to whether the invitation extended to all-Ireland bodies or ‘clearly discriminated between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland’. Some N.I.A.A.A. members, notably its assistant secretary, Tom Ferguson, expressed doubts about communicating with other ‘kindred sporting organisations’ to enter a Northern Ireland contingent, because these might accept the invitation as all-Ireland bodies. Unionist press coverage in Northern Ireland concurred that difficulties would arise for the N.I.A.A.A. if other sports might select B.E.G. teams from all over Ireland and it also stressed that the letter from the Empire Games Committee specifically stated the intention to invite teams from Northern Ireland and the Free State.Footnote 86

The N.A.C.A. were invited to nominate a team, but the British hosts stipulated that the athletes be from within the Irish Free State. The N.A.C.A. declined the invitation on this basis at their annual congress. N.I.A.A.A. minutes in January 1934 note that ‘the Free State had intimated their intention to compete in the European Games only’.Footnote 87 Together, the Empire Games Council (of England) and the N.I.A.A.A. ensured that Northern Ireland had separate athletic representation in 1934. By April, the Belfast Telegraph reported that the Free State would probably be ‘the only dominion unrepresented’Footnote 88 and the Belfast News Letter and Northern Whig confirmed that Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales were to have independent representation after a meeting of the A.A.A.Footnote 89 In July 1934, the N.I.A.A.A. unanimously agreed to nominate athletes.Footnote 90 Attesting to this, a singlet, worn by triple jumper Eddie Boyce from North Belfast Harriers (figure 5), captures the official team title and crest: a crowned blue cross with a red hand of Ulster. The official 1934 programme (in the authors’ private possession)Footnote 91 also lists the athletics team entry. John/Jack Parker, a Brighton-registered runner, competed in the three-mile race, Bertie Shillington and Maurice Tait (also spelt Tate) in the long jump, Ian Bell in the 100/200 yards and D. J. Corr in a cycling time trial. Boyce, hop, step and jump, was reported as feeling unwell during the games,Footnote 92 and was placed third and fourth in this event by differing sources. N.I.A.A.A. minutes of September of that year note that they received much criticism for the selection of Tait,Footnote 93 who was reported by the Belfast Telegraph as unplaced in the long jump.Footnote 94

Figure 5. 1934 team title and crest

Credit: North Belfast Harriers Collection (photo by authors).

The 1934 lawn bowls team was titled ‘Ireland’ (in newspaper reports,Footnote 95 on the official scoreboard and in reports across the Empire) (see figure 6). Other accounts refer to Northern Ireland as the team title, most likely because, though it was an all-island body, the Irish Bowling Association selected a team from northern clubs.Footnote 96 They were runners-up, and their success was described in some detail under the byline ‘Ireland's Pluck’ in Ireland's Saturday Night, which stated: ‘Well played Ireland. This salutation, often heard at the Empire championship games this week, will find a warm echo in the hearts of all Irish bowlers. The Irishmen were making their debut, and happy and successful it was.’Footnote 97 Ireland's bowlers competed again in 1938 but were unsuccessful.

Figure 6. 1934 lawn bowls scoreboard

Credit: Still taken from British Pathé, Film ID 769.23 Body-line Barred, available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=NHKKlKlkaVw.

In 1934 the sport of swimming was highly contentious from an Irish perspective. In May 1934, the Irish Amateur Swimming Association (I.A.S.A.) referred the question of taking part to their emergency committee.Footnote 98 Some months later, they published a detailed statement in the Northern Whig on 4 August 1934, under the byline ‘Ireland not represented in swimming events — Entry refused — English Council introduces politics’. This revealed some of the contents of correspondence with the hosts (via Evan Hunter/Empire Games Council secretary and A.A.A.).Footnote 99 It was clear that relations had become quite barbedFootnote 100 because of the insistence of the I.A.S.A.'s claim to all-island jurisdiction and, thus, to the title Ireland. Hunter said ‘we must keep to the political style and title of the respective territories by which they are known within the British Empire’.Footnote 101 His interpretation mirrored official British government guidance three years previously, that the term ‘Ireland’ acknowledged the geographic actuality but, politically, the island comprised two governments and two territorial divisions. The I.A.S.A. regarded Hunter's opinion as ‘absurdly illogical and entirely unsustainable’ and ‘unnecessarily biased and inconsistent’, and, in response, the I.A.S.A. secretary (1930–36), Frank Cunningham, said that ‘we endeavour to keep sport and politics apart’.Footnote 102 The I.A.S.A. lobbied the Stormont government via Commander Oscar Henderson, who was then comptroller in the governor's household. Correspondence on the all-island jurisdiction of the I.A.S.A. and their right to admission at the Empire Games as representatives of ‘Ireland’ was sent onwards to C. G. Markbreiter in the Home Office, who then wrote to the king's secretary, Sir Clive Wigram, about the matter. However, no government official intervened on the record. The Department of Interior (at the Home Office) regarded the matter as outside their official remit, the Secretary of State for the Dominions, James Henry Thomas, having been consulted by Sir James Leigh-Wood, president of the B.E.G. Federation. Thomas took the line, somewhat disingenuously, that this was not ‘the sort of matter in which any form of government intervention’ was ‘at all desirable or even practicable’. This office also advised against an approach to the king's secretary on the matter.Footnote 103

The I.A.S.A. regarded the actions of the British hosts as an ‘intolerant interference’ that propagated disruption and discord rather than strengthening goodwill.Footnote 104 They maintained their right to all-island jurisdiction in the face of British pressure exerted elsewhere via the international swimming association, then known as Fédération Internationale de Natation (F.I.N.A.), but they did not secure an all-island entry in 1934 for a team that was slated to include three northern swimmers. As a result, the I.A.S.A. refused to send any team to London for the 1934 games. Fourteen years later, the I.A.S.A. was forced to withdraw its team from the 1948 London Olympic Games for similar reasons, having included two Northern Irish swimmers.

Another all-island body, the Irish Amateur Boxing Association (I.A.B.A.), took a different route in 1934. It declined an official invitation, based on what it said was the association's closed season, and granted exemptions to individual R.U.C. and Garda Síochána members to compete, possibly a decision taken in the interests of sport and individual boxers.Footnote 105 A report in the Midland Counties Advertiser claimed that two boxers from Birr Boxing Club had been entered for the games.Footnote 106

Dawson Bates resisted any all-island authority invested in the I.A.B.A. (as he had done previously with the N.A.C.A.). Having been asked by a Belfast unionist politician, William Grant, whether the R.U.C. boxing team could enter,Footnote 107 Dawson Bates considered it desirable ‘to send members of the force to represent them’. Medals were won by R.U.C. boxers, Willie Duncan and Jim Magill, at welterweight and middleweight respectively. These were officially credited by the British organisers to Northern Ireland despite the boxers having no official sportive status to that effect (figure 7).Footnote 108 Two years later, Magill (figure 8) was selected by the Irish Olympic Council for the 1936 Olympics. Not only did the R.U.C. authorities refuse him permission to compete for Ireland, but British Olympic officials exerted their right to select him. Following an official complaint from the I.A.B.A., Magill did not compete in the Berlin Olympics, which were also boycotted by the Irish Olympic Council. Thus, it can be seen that while activities were well underway to bolster the political status of Northern Ireland, the national eligibility of athletes within some sports was ambiguous and jurisdictional rights were still contested. Divisions in Irish athletics hardened further over the next four years, such that, by 1938, a third men's athletics body was formed on the island. The Amateur Athletic Union of Éire accepted 26-county jurisdiction and became the recognised body affiliated to international athletics. Though duly suspended from international athletics, the N.A.C.A. retained the support of most athletic clubs on the island.

Figure 7. 1934 boxing medal won by Jim Magill

Credit: R.U.C. Athletic Association memorabilia, Newforge, Belfast.

Figure 8. Constable Jim Magill

Credit: The Daily Mail, 27 June 1939

VI

The third Empire Games were held in Sydney in February 1938. This host city was decided at a meeting of the Empire Games Federation on 4 November 1935, at which it was reported that England, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, Canada, Scotland, South Africa and Wales were present, but not Northern Ireland.Footnote 109 By then, the I.A.A.F. had formally suspended the N.A.C.A. from international athletics for not accepting their political boundary ruling. After being lobbied by the British, de Baillet-Latour (I.O.C. president) and Edström (I.O.C. vice president) led the move to cement the adoption of the political boundary rule. But, some Olympic officials had expressed reservations. De Coubertin wrote that ‘Ireland in its new form … could not be properly split in two’ because the Irish Olympic Committee was first accepted as a member country, not as a state.Footnote 110 In February 1936, the N.I.A.A.A. recorded the consequences of the political boundary ruling and the international suspension of the N.A.C.A., which was that ‘no organized governing association could compete with or against the N.A.C.A. without also courting immediate suspension’.Footnote 111 A few months later, the Belfast News Letter, Northern Whig and Belfast Telegraph reported that provision had been made by the Australian organisers of the 1938 Empire Games to bring two athletes from Northern Ireland.Footnote 112 In March 1937, it was reported that the International Bowling Board were ‘holding back the arrangements for the British team they were sending to visit Australia until such time that the Australian Council could give a guarantee that none but official bowling teams would be recognized from the British Isles’.Footnote 113 At their annual congress in February 1938, the N.A.C.A. was addressed by former Irish Minister for Posts and Telegraphs, J. J. Walsh, who applauded the association ‘for keeping the national banner floating’.Footnote 114

Some months before the Sydney games, the Dominions Office clarified with its various representatives that for official British purposes the title Irish Free State was to be replaced by Éire or Ireland, and Downing Street also insisted that the title United Kingdom and Northern Ireland be used officially to ‘avoid referring to Ireland when references to Éire are intended’.Footnote 115 Likewise, under British prompting, the International Olympic Committee had by then moved to adopt Éire as the title of their member. Though Irish representatives wrote to them to affirm their official title was Ireland when using the English language and, if using Irish/Gaelic, then Éire, this was ignored by the I.O.C. Correspondence continued throughout 1938 on the name of the Irish Olympic team and concerning the new (and numerically smaller) Irish athletics association that accepted the political boundary rule. Reflecting their recognised status, N.I.A.A.A. minutes record that in February 1938 they were asked by the British Amateur Athletics Board (retitled so in November 1937)Footnote 116 for their viewpoint in relation to the international affiliation of this new Irish Free State body.Footnote 117 This was the same month as the third Empire Games were held.

These games were not as strongly supported across the empire. Lengthy travel to Australia, high costs, and the need for extended leave for competitors were explanatory factors. Even so, the diplomatic and propaganda benefits were recognised, however belatedly, by Dawson Bates who, having received representation from the N.I.A.A.A.,Footnote 118 sanctioned leave for R.U.C. athletes to compete. The official 1938 programme lists thirteen visiting teams including Northern Ireland but, as in 1934, ‘Ireland’ competed in lawn bowls.Footnote 119 The Irish Free State Bowling League was invited to participate but did not accept owing to prohibitive travel costs. It voted to change its title to the Bowling Association of Ireland, the alternatives Éire and the Southern Section having also been considered.Footnote 120 This sport was among a list of eight on the 1938 programme that included athletics, swimming, cycling, boxing, rowing, diving and wrestling.

A photograph of the Northern Ireland athletics team was included in the official 1938 report (figure 9). This team included Shillington, also a 1934 competitor. He had first competed under the N.A.C.A. before being selected by the N.I.A.A.A.Footnote 121 Chairman of the B.E.G. Council for England, James Leigh-Wood, wrote to the N.I.A.A.A. ‘urging the desirability of having Northern Ireland represented at the games’.Footnote 122 He also wrote to Lord Craigavon on 13 August 1937 to seek his support for granting extended leave to two R.U.C. officers (Alex Haire and John Clarke),Footnote 123 who were to form part of the British travel contingent to Australia. Initially, the participation of R.U.C. members was not regarded by Dawson Bates as being ‘in the public interest’, given that their services would be lost for a prolonged period. He concluded that: ‘the representation from the R.U.C. could not be sufficiently numerous to be effective from the point of view of propaganda … their identity would be simply submerged in the very large number of competitors who will take part in these Games’. He did ‘not think it right that the public should be deprived of the services of these men for a period of perhaps more than four months’.Footnote 124

Figure 9. Northern Ireland athletics team 1938

Credit: British Empire Games Souvenir Programme

However, political pressure was exerted on him and on the prime minister. At question time in the Stormont House of Commons on 20 October, Dawson Bates was asked about his decision by Mr Midgley of the Northern Ireland Labour Party, who highlighted the ‘honour and prestige which would accrue through Northern Ireland's participation [that would] far outweigh the value of the services that the men might contribute in the interim period’.Footnote 125 And having replied to Leigh-Wood to explain that various reasons prevented the release of R.U.C. personnel, including the issue of extended leave, Craigavon's secretary wrote some weeks later to revise this view.Footnote 126 Between August and November 1937, Dawson Bates was also lobbied by the N.I.A.A.A.,Footnote 127 and it was finally agreed that the Northern Ireland team would travel to Australia with the English and Scottish teams.Footnote 128

This piece of sportcraft was reported in the Belfast Telegraph on 5 November 1937 under the headline ‘Police Athletes for the Empire Games — Decision of Ministry’ and in the Belfast News Letter on the same day. A message from the N.I.A.A.A. president, Major Baird, to the athletes was printed in Ireland's Saturday Night on 27 November 1937, which reaffirmed their symbolic representational value and read: ‘I have every confidence that the athletes selected from Ulster will do all they can to achieve it [success] and to uphold the proud prestige of the province … the honour of Northern Ireland is safe in their keeping.’ In the same paper it was also reported that ‘Northern Ireland will thus be able to participate in the Empire Games, and there is no doubt her representatives will worthily uphold the prestige and sporting traditions of the province’. The Prime Minister also sent a telegram to Leigh-Wood wishing good luck to ‘Ulster's contingent and the other representatives of the homeland on their departure for Australia’.Footnote 129

The 1938 souvenir programme records that the official flag of Northern Ireland was displayed on a flagstaff at the games village. In the opening ceremony, teams lined up behind flags and, as in previous games, the oath of allegiance was sworn to the monarch by one athlete on behalf of all. The ‘athletic form’ of the three members of the Northern Ireland team was outlined in one press report under the byline ‘Ulster competitors’.Footnote 130 Elsewhere in the same newspaper was a celebration of the ‘loyal sentiment of Ulster, which so much prizes its place within the Empire … Not one of the 500 Empire athletes now ready for the fray in Sydney represents Southern Ireland.’ The Larne Times reported the attendance of an Ulster representative, Lieutenant Colonel Gordon M.P., at the pageant to mark the opening of the 150th celebrations of New South Wales, held on the same day as the Empire Games finals.Footnote 131 Field athlete John Clarke was reported to have been ‘outclassed’ in the javelin and Alex Haire was forced to retire in the half-mile heat owing to ‘a recent indisposition’.Footnote 132

At the conclusion of the games, it was acknowledged by the athletics writer, ‘Spiked Shoe’, in Ireland's Saturday Night that the Northern Ireland representatives ‘were up against better men’.Footnote 133 This writer, however, lauded the ‘capable display’ of Shillington, who placed sixth in the final of the hop, step and jump. The outbreak of World War II led to the suspension of all international sport. But, the British Empire Games Federation, which was dominated by the A.A.A., had already expressed a disclination to participate in Olympic Games held in any country at war.Footnote 134 The London ‘Austerity’ Olympics in 1948 signalled the relaunch of the Olympic movement after this hiatus, the growing role of sport in international relations, and a new phase in statecraft and sportcraft.Footnote 135

VII

The British Empire Games of the 1930s were used to underline and reinforce empire solidarity. The choice of Canadian, British and Australian host cities reflected this. The games also reveal how centralised sports authorities often governed in their own interest, sharing beliefs, conventions, ideas and practices. At the heart of the actions of these bodies were questions of national identity that, in the Irish case, led to a hardening of the sportive border in athletics. These issues were signalled in official pronouncements from national and international sports bodies. But, Stormont leaders also intervened to cement both their identity and place within the United Kingdom, their right to sportive jurisdiction and their contribution to empire. National symbols such as flags and emblems also played a key role in these expressions of identity.Footnote 136

Such issues appeared in discussions concerning the 1930 Hamilton Games. Irish Olympic Council President, J. J. Keane, also an executive member of the I.O.C., saw ‘no reason why … a flag should make any difference to a man who wins for his country’.Footnote 137 Thus, the adoption of the harp flag (on either a blue or green background) for the 1930 Games can be seen as an attempt to project an inclusive vision. By 1938, however, clear lines had been drawn in terms of state formation such that the flag, emblem and title of Northern Ireland were clearly delineated in all Empire Games material. The B.O.A. adopted the team title ‘Great Britain and Northern Ireland’ at the 1948 Olympics to counter the continued claims of the N.A.C.A. and Irish Olympic Council to all-island jurisdiction.Footnote 138 This was not formally endorsed by the I.O.C. and the B.O.A. reverted to ‘Great Britain’ for the 1952 Olympics. Moving in a different direction, the Irish Rugby Football Union adopted a flag in 1925 which incorporated four provinces with the shamrock logo, they selected players from throughout the island of Ireland, and international matches were then played in both Dublin and Belfast.Footnote 139

This paper has explored the historical interconnected practices of state formation, national identity via consideration of Irish involvement in the British Empire Games, and the sportcraft practiced by politicians and sports officials north and south of the border. It is clear from the evidence presented here that by the late 1920s and into the 1930s, government officials and sports administrators had already recognised the propaganda functions and utility of sport to state formation in Ireland and Northern Ireland and to issues of political control, jurisdiction and territorial boundary-keeping. Sport played a propaganda role north and south of the border. While the beliefs of northern and southern male elites may have differed concerning the acceptance of partition — political and sportive — their actions were driven by similar motives of nationalism and nationhood. Throughout this period, sportive and political elites in Ireland resisted British and unionist pressure, and they continued to advocate for a thirty-two-county Ireland.Footnote 140