Article contents

Persian Progressive Tense: Serial Verb Construction or Aspectual Complex Predicate?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2022

Abstract

The present and past progressive tenses in Persian are the only tenses in which both the main verb and the minor verb dâštan “to have” receive agreement marking. Morpho-syntactically, Persian progressives show the similar properties of both Aspectual Complex Predicates and Serial Verb Constructions. The question that this paper addresses is: are Persian progressive tenses Aspectual Complex Predicates or Serial Verb Constructions? By presenting the morpho-syntactic and semantic analysis of Persian progressives, and highlighting the main properties of Aspectual Complex Predicates and Serial Verb Constructions, the paper shows that, despite the similarities between these verbal constructions and Aspectual Complex Predicates, Persian progressives are instances of Serial Verb Constructions where neither a complementizer nor a conjunction separates the two verbs and the complex describes a single conceptual event.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Iranian Studies , Volume 43 , Issue 5: On Persian Language and Linguistics , December 2010 , pp. 607 - 619

- Copyright

- Copyright © The International Society for Iranian Studies 2010

Footnotes

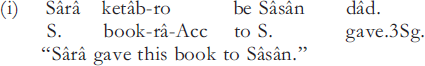

Abbreviations: Acc = Accusative, Ez = ezafe, F. = feminine, ImP = imperfect, Incl = Inclusive, N = name, Nom = nominative, Past = past, Pl. = plural, Pres = present, Sg. = singular, Stm = Stem.

References

1 Bybee, Joan, Perkins, L. Revere, and Pagliuca, William, The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect, and Modality in the Languages of the World (Chicago, 1994), 133.Google Scholar

2 Bybee et al., The Evolution of Grammar, 136.

3 Bybee et al., The Evolution of Grammar, 130.

4 Butt, Mariam, The Structure of Complex Predicates in Urdu (Stanford, CA, 1995), 102Google Scholar: e.g. 23.

5 Comrie, Bernard, Aspect (Cambridge, 1976), 33–35.Google Scholar

6 Comrie, Aspect, 25.

7 Holger, Tröbs, “Progressive and Habitual Aspects in Central Mande,” Lingua, 114 (2004): 126.Google Scholar

8 Bybee et al., The Evolution of Grammar, 128.

9 Schultze-Berndt, Eva, “Simple and Complex Verbs in Jaminjung. A Study of Event Categorization in an Australian Language” (PhD diss., University of Nijmegen, 2000), 36.Google Scholar

12 Butt, The Structure of Complex Predicates in Urdu, 224: e.g. 44b.

10 Butt, The Structure of Complex Predicates in Urdu, 222.

11 Butt refers to these SVCs as complex predicate constructions, but they are not the same as true Persian complex predicates.

13 Butt, The Structure of Complex Predicates in Urdu, 224.

14 Butt, The Structure of Complex Predicates in Urdu, 225.

15 Sebba, Mark, The Syntax of Serial Verbs (Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 1987), 2.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

16 Christaller, Johann Gottlieb, A Grammar of the Asante and Fante Language called Tshi (Basel, 1875, republished in 1964), 63–75.Google Scholar

17 Seuren, Pieter A. M.. “Serial Verb Construction” (Ohio State University Working Papers in Linguistics 39, 1990), 18–23.Google Scholar

18 Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. and Dixon, R. M., Serial Verb Constructions: A Cross-linguistic Typology (Oxford, 2006), 1–56.Google Scholar

19 Concordant marking means that each component of SVC takes the marker. For example, in the case of personal endings, each component of SVCs takes the personal ending.

20 Butt, The Structure of Complex Predicates in Urdu, 102: e.g. 23.

21 Folli, Raffaella, Harley, Heidi and Karimi, Simin, “Determinants of Event Type of Persian Complex Predicates,” Lingua, 115 (2005): 1365–1401.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

22 Kayne, Richard, Towards a Modular Theory of Auxiliary Selection (CUNY, Ms. 1993).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

23 Rosen, Sara Thomas and Ritter, Elizabeth, “The Function of ‘Have’,” Lingua, 101, no. 3/4 (1997): 295–322.Google Scholar

24 See Azita H. Taleghani, “Possessive Construction in Persian” (Unpublished paper, 2006), 16

25 Direct objects are marked by râ if they are specific. This is illustrated by the following example.

It is worth noting that the particle râ is a specificity marker that appears with nominal elements that receive accusative case. In spoken language, râ is employed as ro and o. See for detailed analysis: Karimi, Simin, “Specifically Effect: Evidence from Persian,” Linguistic Review, 16 (1999): 125–141CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Lazard, Gilbert, A Grammar of Contemporary Persian (Cosa Mesa, CA, 1992)Google Scholar; Ghomeshi, Jila, “Projection and Inflection: A Study of Persian Structure” (PhD diss., Department of Linguistics, University of Toronto, 1997).Google Scholar

26 See Hashimipour, Margaret, Pronominalization and Control in Persian (PhD diss., University of California, San Diego, 1989).Google Scholar

27 Karimi, Simin, A Minimalist Approach to Scrambling: Evidence from Persian (Berlin, 2005), 12CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Ghomeshi, Jila, “Control and Thematic Agreement,” Canadian Journal in Linguistics, 46 (2001): 9–40.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

28 See Karimi, A Minimalist Approach to Scrambling, 29.

29 Taleghani, Azita H., Modality, Aspect and Negation in Persian (Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 2008), 162.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

30 Butt, The Structure of Complex Predicates in Urdu, 102: footnote 7.

31 Seuren, “Serial Verb Construction,” 18–23.

32 Taleghani, Modality, Aspect and Negation in Persian, 177.

- 3

- Cited by