Persian remained one of the major literary and documentary languages of the Indian Subcontinent for over eight centuries.Footnote 1 We may distinguish between Persian texts that locate themselves within the larger domain of the Persianate world and elaborate on themes provided by the canons of Persian knowledge, and texts meant to broaden the scope of this inherited canon. When the Persian-knowing literati of the Subcontinent endeavored to explore unknown territory of the regional cultural traditions, it is in Persian that they conveyed this newly acquired knowledge. The effort to produce a body of texts on Indic culture started as early as the Ghaznawid period, and carried on throughout the Sultanate period, and up to the famous translation projects of the Mughals, and Akbar in particular, which was continued in some way by the British in the early colonial period. Indo-Persian works on Indic knowledge are often based on the study of texts and engage with learned traditions. This is the most visible part of this corpus constituted of translations of texts written in Sanskrit and other South Asian languages.Footnote 2 But access to Indic texts was often mediated orally, and, in many cases—as in the rendering of treatises on music and lyrical arts (saṅgīta), Persian tarjomehs also recorded updates based on the observation of the living tradition that surrounded the transmission of written treatises.Footnote 3 The Customs of the Magh should thus be considered within this longstanding Indo-Persian tradition to push further the boundaries of knowledge beyond the study of texts, through firsthand observation of living cultural practices.

The particular context that surrounded this report requires that we consider other major factors that conditioned its production. The text actually steps beyond the usual scope of Indo-Persian encyclopedism: it records the rites that punctuate the life of Buddhist Arakanese who lived in southeastern Bengal. This report, and the archive from which it was extracted, testifies to an attempt by the East India Company to gather information (intelligence?) regarding a threatening neighbor: the kingdom of Arakan until 1784, and after that date the emerging Burmese empire. This moment of the history of the EIC in Bengal is characterized by important changes in the modes of information gathering and the production of knowledge about India.Footnote 4 Those changes, which consisted in the combined approach of firsthand observation with a close study of languages and texts, apparently matched the Persianate approach that brought together translation per se and personal observation. The main difference though was that, in the European case, both textual sources and observations made on the ground ought to remain clearly distinct. This distinction quickly led to the creation of orientalist philology as a discipline separate from the study of contemporary forms of knowledge. In this early colonial context, Persian accounts on India and “India beyond the Ganges” (i.e. mainland Southeast Asia) became obsolete because of the mix of textual and observational knowledge that characterized those texts. Another related factor that accelerated the obsolescence of Persian texts on regional cultures was the densely mediated nature of such accounts. The gathering of information often involved oral interactions in one or more vernacular languages before the redaction of the Persian text.Footnote 5 What we end up reading is thus a palimpsest involving the use of several idioms with their specific conceptual and semantic constraints that was eventually laid down in a highly regimented Persian written idiom. As fascinating as it may be for the student of the cultural history of South and Southeast Asia today, such polyphony hardly matched the agenda of the East India Company. This is why Persian was soon relegated to the exclusive domain of administration and legal matters. As a result, the vast corpus of Persian texts on Indic traditions remained virtually unstudied for decades.Footnote 6

The Murray archive is a striking example of the general lack of interest for what was seen as secondhand sources for the study of South and Southeast Asia.Footnote 7 John Murray-MacGregor was not an orientalist and, despite his knowledge of Persian—and probably some Sanskrit and Bengali—and his vast manuscript collection, he did not publish any scholarly works on the history or religions of Bengal and the surrounding regions where he extensively traveled. His knowledge of “oriental languages” was primarily practical and his manuscripts were mostly copied for him by his monshis (Persian-knowing clerks), therefore these were not ancient or luxury manuscripts that were sought by erudite antiquarians involved in the making of orientalist knowledge.Footnote 8 The texts that he collected represented either the common literary culture of the time in Bengal, or they were the product of targeted surveys and projects linked to his activities at the service of the East India Company.Footnote 9

The texts on Arakanese Buddhism collected by Murray represent a typical attempt to describe the fundamentals of a nation in late eighteenth-century Europe. After surveys on trade, agriculture, and goods produced in a given region, agents of the EIC tried to grasp the tenets of a nation’s institutions (i.e. its legal texts), its religious doctrine and practices, and its understanding of geography and natural sciences. In the present case, this approach is best encapsulated by the writings of Michael Symes (1761−1809) and Francis Buchanan (1762–1829) published after their embassy in Ava in 1795.Footnote 10 As a matter of fact, Murray’s texts were used in order for Symes and Buchanan to write their reports on the religion and customs of the “Burmas.”Footnote 11 In addition to this, they also gained access to the Latin writings of the Barnabite missionary Vicentius Sangermano (1758–1819), which included direct translations from Burmese and Pali texts as well as observations that he made over his extended stays in Pegu and Ava.Footnote 12 This moment constituted a watershed in the European knowledge of Burma and what would eventually be called Theravāda Buddhism.

The present document belongs to this formative moment of European studies of Buddhism. After Symes’ embassy to Ava and with the orientalist works on Sri Lanka and Tibet, the information contained in Murray’s text on Arakan must have seemed too “provincial” and unreliable due to the Persianate mode of information gathering that I mentioned above. Why would Arakanese Buddhism be provincial? The first reason is that already when Symes and Buchanan traveled to Burma, Arakan had ceased to exist as an independent political entity and was a province of the Burmese empire. The second reason is that those texts were collected from the region of Chittagong, where, according to Buchanan, the form of Buddhism that was practiced was corrupt in comparison with the orthodox Buddhism of Arakan proper and of Burma.Footnote 13

Because of the gradual erasure of the political and religious past of Arakan after the Burmese conquest and the reformist movements that were active in the region in the nineteenth century, we know very little about the specific features of Arakanese Buddhism. Therefore, Murray’s translations and this short report on the religious customs of the Magh in particular, are invaluable sources for the study of Arakanese Buddhism as it was practiced in Chittagong before the reformist period.

The text was written by a Hindu monshi, Rāy Jaganāth Sahāy, at the request of John Murray himself.Footnote 14 It is written in plain Persian prose and displays a clerical style typical of the documents found in his archive. I have divided the text into eleven sections. After the basmala the text opens on the praise of the commissioner of the text and indicates that Rāy Jaganāth Sahāy gathered his information on the basis of a written report provided by a monk (rāvali). The themes treated in the following sections are: (2) birth ritual; (3) naming and feeding of the infant; (4) temporary ordination around the age of twelve; (5) arrangement for the marriage; (6) wedding ceremony; (7) remarriage of widows; (8) miscellaneous customs and bodily hygiene; (9) funeral rites; and (10) ordination ceremony. The text ends with a colophon, in which the copyist provides the date the text was written down (1210/1796).

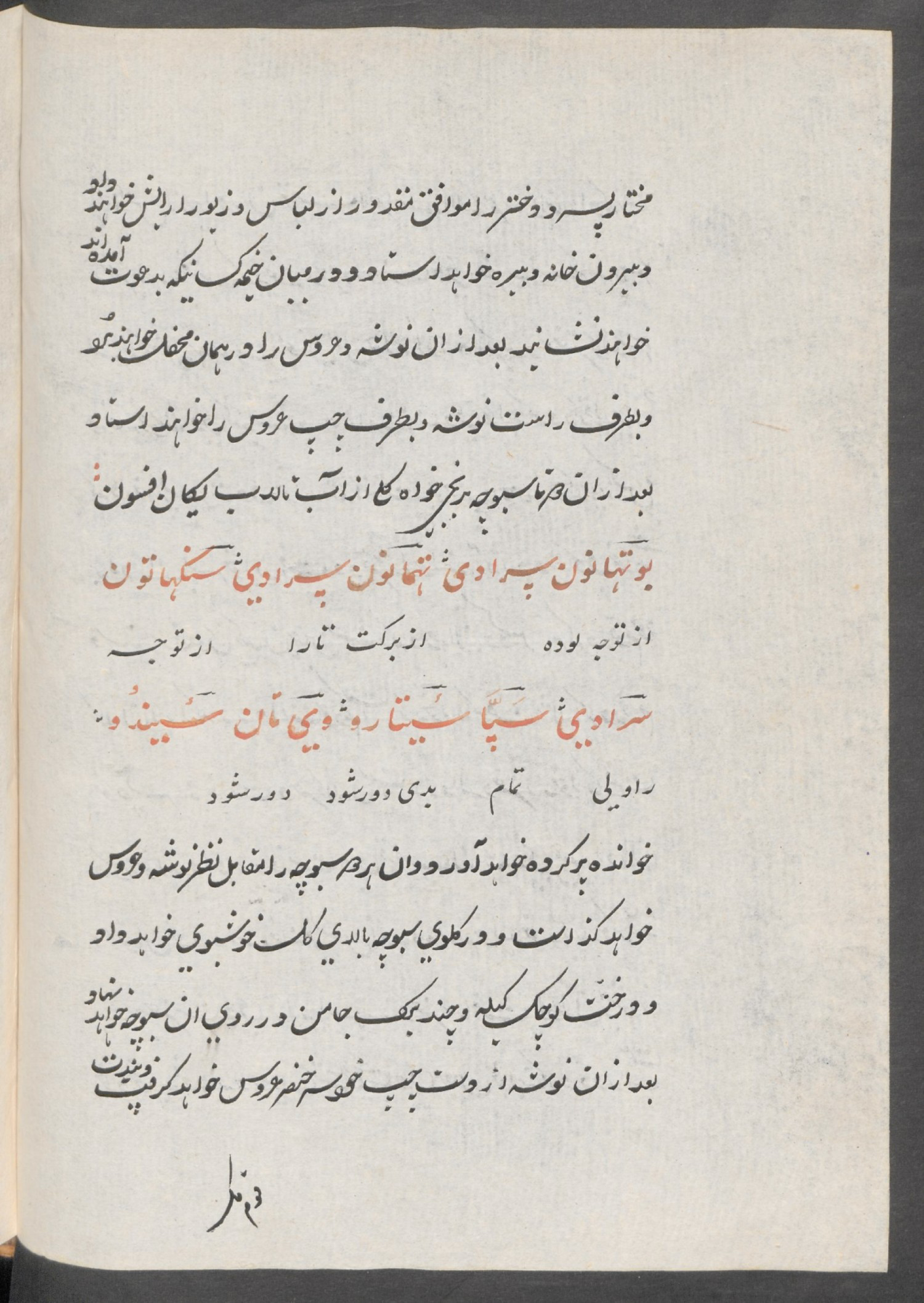

Figure 1. Rubricated transcription in nastaʿliq of an Arakanese prayer. STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Orientabteilung, Ms. orient Fol. 306, fol. 83b.

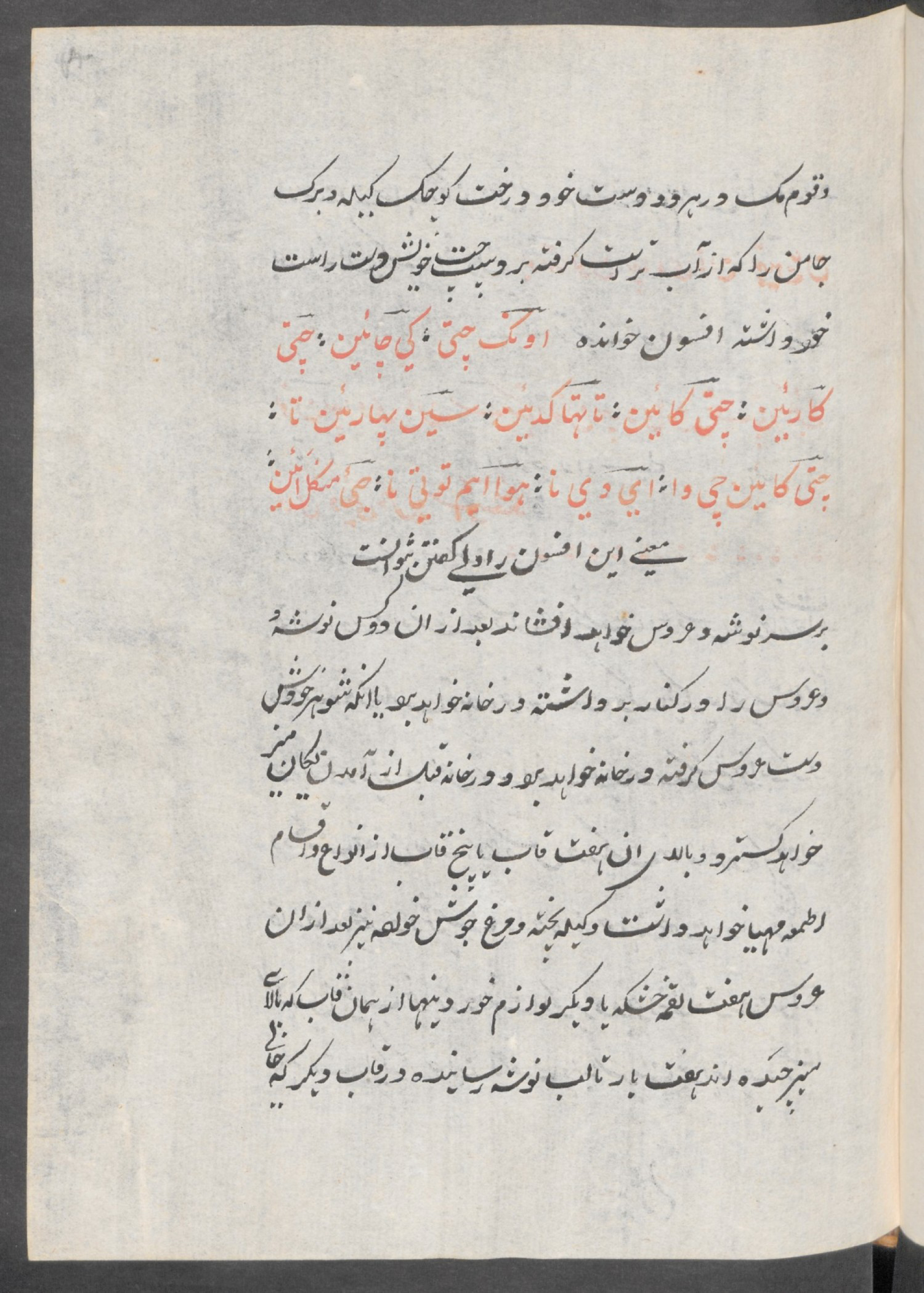

Figure 2. Rubricated transcription in nastaʿliq of an Arakanese prayer. STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Orientabteilung, Ms. orient Fol. 306, fol. 84a.

Source: Wilhelm Pertsch, Die Handschriften-Verzeichnisse der königlichen Bibliothek zu Berlin, 508 [MS no. 532.5; Ms. orient Fol. 306, fol. 83b and 84a].

Below, I give a complete translation of the text with annotations, in which I provide parallels from Sangermano’s description of the Burmese empire, as well as Buchanan’s survey of the Chittagong Hill Tracts and an article that he published in 1801 on “The Religion of the Burmas” in Asiatick Researches. Footnote 15

In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate

-

[1] The religious customs of the Magh according to the report (newisānideh) of a monk (rāvali),Footnote 16 which was committed to writing by the servant Rāy Jaganāth Sahāy on the order of the exalted and bountiful lord, the generous and benevolent to those in need, Mister Jān Mare (i.e. John Murray) sāheb—may the Exalted perpetuate his fortune!

-

[2] When a Magh has a son or a daughter, within three to five days after the birth, preserving some hair, they shave the rest and bathe [the baby]. Then, they feed their relatives, far and near, according to their means.Footnote 17

-

[3] They also give alms to the monks. On the same day they inquire from an astrologer about the good and bad omens of his horoscope and they name the infant. Five months after the birth, they start feeding him grain.Footnote 18 On this joyous occasion they serve food to their close and far relatives according to their means. Those who come to eat put some money in the baby’s hand to the extent of their ability.

-

[4] After he turns twelve years old he may pierce the lobes of his ears any year.Footnote 19 Sometimes, they begin when one turns thirteen. From that year, those who are favored by God become moyshāngs—that is to say a disciple (morid).Footnote 20 Whenever one becomes a disciple, he must wear a golden robe. Among their duties, according to the book of disciples (ketāb-e morid), during a period of seven days they must sustain themselves by begging food and other alms from the houses of the Magh. During these seven days, they must not light fires, or touch pieces of metal such as iron, silver, or gold. They must also abstain from eating fish or meat. These are among the duties of the disciple. On the eighth day someone takes off the golden robe from their body. Until someone reads the injunctions of his religion to the monk, he is given the above-mentioned robe and is free to study according to his ability. [Then,] he exchanges his golden robe for a white one. He hangs that golden robe to an Ashvattha tree (i.e. sacred fig) and does not give it to [another?] monk. After that, he learns another spell (afsun) from a monk, comes among the lay people of his community, and he is called a Magh (qowm-e mag).Footnote 21

-

[5] Because he became a lay person, he must get married.Footnote 22 There is no specific age for the Magh to get married. After they turn twelve, they can marry whenever they want. The custom regarding marriage among the Magh is as follows: When someone has a son, he appoints a person as a representative and sends him to the house of the girl he heard about. The representative goes there and finds out about the girl’s pedigree. To the girl’s father’s request, [the representative] presents the boy’s pedigree. If the pedigrees of both parties are compatible, the representative would present the intention of the person who appointed him (movakkel) to the girl’s father. If the girl’s father agreed, then they call an astrologer who verifies the compatibility of the boy and the girl’s horoscopes. When the stars agree in the calculation of a Brahman, then they inform the boy’s father. If the boy’s father is alive, he himself prepares ear-ornaments made of gold or silver and will hand them over to the representative. Some people among the close relatives will go along and give it to the girl. When they have given the ornaments to the girl, the wedding is set. If the boy’s father is not there anymore, the boy will himself arrange everything. If the girl's father wants the wedding to be at his house, the boy will organize it at his place. If it is decided that the wedding would take place at the boy’s house, according to a fixed rule, some brothers of the boy will go and bring the girl and the wedding would take place.

-

[6] Here is how a Magh wedding takes place: Of those two, the one whose status is superior will take gold from the one whose status is inferior. For instance, if in his own people the boy is of a superior status, he will take gold from the girl’s father, if not, he will have to give [gold]. On the day of the wedding, all the brothers and members of his community will be brought to his place and served food. If the wedding takes place at the girl’s father’s home, he will himself invite the brothers and members of the community. The wedding will be fixed in the middle of the night, and at the chosen time, the boy and the girl will be adorned with garment and jewels according to their means. They will go out of the house and stand on a by-road (bīrah?).Footnote 23 They will seat in a tent all the guests who came. After that, they will bring the groom and the bride into this gathering, and the groom will stand on the right side and the bride on the left side. Then, they will recite a spell:

They bring two pots filled with rice or flowers from the waters of the pond. They place both pots in front of the groom and the bride. In the neck of the pot, they will sprinkle perfume upon the flower. They would place small plantain trees (kela) and some leaves of jamunFootnote 25 in front of the pots. Then the groom would grasp the tip of the bride’s little finger with his left hand. The Magh pandit takes the small plantain and the jamun leaves, which are wet with water, with both hands and puts his right hand on his left hand and recites this spell:buthānun sarādi . thamā nun sarādi . sankhā nun sarādi . sappā sitā ru . wi tān soyndu Footnote 24

az tavajjoh-e budh[.] az barakat-e tārā[.] az tawajjoh-i rāvali[.] tamām badi dur shavad[.] dur shavad[.]

“By the Buddha’s favor. By the blessing of Tārā (i.e Dharma). By the favor of the monk(s). May all ills be removed. May they be removed”

He would throw it on the heads of the groom and bride. After that, two people would take the groom and bride in a corner and bring them in the house or the husband would himself take the bride to the house. In the house, before they arrive, a table would be dressed and on it seven or five plates with various food items would be prepared, and they would also eat baked plantain and boiled chicken. After that, the bride brings seven handfuls of rice, or some other food from those plates that were gathered on the table, to the lips of the groom and throws them in an empty plate. The groom would then perform the same action. Then, they recite the spell:unak chati. ki chāʾin. chati kāraʾin. chati kāʾin kadaʾin. sin phāraʾin tā. chati kāʾin chi dā . ay di nā. hawā in tuti nā. jaʾi mankal aʾin. Footnote 26

––The monk could not tell the meaning of this spell––

After that, they wash the hands of the groom and the bride. The bride will enter the house. The groom will join the gathering and sit. He will feed the guests and they will watch a dance show. They will light up [the place]. When it is time to sleep, the groom and the bride are given a room where they will sleep, because the outside of an old house has no sign of renovation.Footnote 28 On their bed they will hang fragrant flowers. If they are both young and are overcome by bestiality, they will mingle and get intimate. In this way, they will sleep together for six days. On the seventh day, they will bathe and begin the householder life.buthā nun phāwi nān. thin mān nun phāwi nān. sankhā nun phāwi nān. sappā aʾin dari daʾi nān sayndu. Footnote 27

az tawajjoh-e budh[.] az barakat-e tārā[.] az tawajjoh-i rāvali[.] hameh dar doʿāguʾi dur shavad[.]

By Buddha’s favor. By the blessing of dharma. By the favor of the monk(s). In the recitation of prayers all [misfortunes?] should disappear.

-

[7] If the fire of the widow’s lust has been extinguished by the water of the loins (māʾ al-solb; i.e. semen) of her first husband, then she will not remarry. Otherwise, after seven days have passed since the passing of her husband, the widow is entitled to choose any man of her liking and will marry him. The marriage is arranged in such a way that the widow will bring [the man] to her house. On a table seven or five plates of the food mentioned when dealing with the wedding will be prepared. The pandit (i.e. learned brahman) will make both of them choose a spell. She will bring seven handfuls of food up to her husband’s lips. The husband will perform the same action. He will bring her in the house and extinguish the intense fire of her lust with the pure water of passion.

-

[8] Taken from the Akāsā dakāsā: māsāyān di amin. These are the formulas of their faith (kalemāt az imān-e khwod), which people from all origins can say to become Magh. Repeating these formulas twice as well as the ten precepts (tārās) is incumbent upon all Magh.Footnote 29 The Magh should not treat any person as an idol and worship him. They do not consider that bathing is a source of merit. If a limb is soiled by some dirt, or because of erotic dreams, or when making love, it is not necessary to bathe and they simply wash their hands and feet. There is a spell that they recite on water, which they sprinkle on their head and with which they wash their hands and feet, turn to the east and invoke creation (yād-e khalq konad) and are cleansed. After urinating they must wash the organ in question with water. In a year they fast for four months. Over the four months during which they will fast, they will go twice to the place of worship (konesht). They can visit the place of worship as often as they please, there is no constraint [in this regard]. They do not kill animals themselves to eat them. If they find one dead, they eat it, because in the Magh religion it is right to eat any dead animal. They do not have relations with courtesans [?].Footnote 30

-

[9] When someone dies, there are two prescribed ways regarding the body: they either burn it or they build a coffin.Footnote 31 When a Magh dies, a monk comes immediately and reads the precepts (tārā) next to him. They lay down the dead on a clean carpet, and they wash him and wrap him in a grave-cloth. They place him on a bed, smear him with fragrance, and hang a canopy above the bed. After this, they prepare a box of the size of his stature and they fix wheels under it. They set up a canopy and throw many fragrant flowers on the deceased, and the people who accompany him, bare headed, bring him to the cremation or the burial ground. If they want to, they may burn the dead with the box. After placing him on a heap of wood, the brother or son of the deceased takes fire seven times in his hand and set him aflame by circumambulating around the dead. Then, those who accompany set him on fire. In the case of an interment, they bury [the dead] with the box. According to their means, they put some iron, silver and gold in the dead’s coffin. After three days, the people who attended [the ceremony] shave, and they feed the monks. Seven days after the death they will feed the monks again and they will listen to the principles from the monks. They will invite and feed their own brethren and give alms according to their means. A year after the death, they will distribute food in the name of the deceased.

-

[10] Here is how one becomes a monk:Footnote 32 Here, a Magh cannot become a monk until he turns twenty. After twenty years, on any given year, if he wishes so and if God favors him, he may become monk. Eighteen monks are required for the ordination (dar shodan-e rāvali): one is the māthi chahrā, that is to say the elder monk; the others are six kāmi chahrā and eleven bhu chahrā aʾin. The eighteen monks will set up a gathering in the town. They will then inquire about who among the Magh people wishes to become monk. This news will be conveyed to everyone. Those who wish to become monks will present themselves to those eighteen monks with all the paraphernalia necessary for the ordination (asbāb va lavāzem-e rāvali shodan). They will dress according to their means and, with plenty of merriment and cheering, they will go along with those monks into a forest dense with trees. In the middle of the forest, if there is a stream, on its bank they will build an ordination hall at the time prescribed by the book of the monks (ketāb-e rāvali), and everyone will sit. After that, the monks will inquire about the pedigree, knowledge, and suitability of the each of them. On a sheet of paper, they will record the names of each according to their ability and status. The rule is that those who are higher in ability, status, knowledge, and suitability will be made monks first, and those who are lower will become monks later. They gather wood and build a kind of enclosure (hasr) next to a stream. Then, they install thirty-two pillars all around and ten in the middle, which makes a total of forty-two pillars. They provide shade with fabric or paper. After that, the elder and the seventeen other monks will go there. The elder himself will sit there and the seventeen other monks will stand behind him. The elder monk will summon four people and they will present themselves in front of him with simple, clean clothes, and they will bow to him. Then, the elder monk will ask three times: “You who are wearing robes and jewels and came in front of me, who are you?” They will stand and answer: “We have heard that the Buddha’s shade is very cool, this is why we came under his shade.” After that, the elder monk will say: “I act according to the order of Lord Buddha. The Lord prescribed that one will not give the formula (kalemeh) to a jenn or a pari or a div who presents himself taking the shape of a human. Speak truly and tell me if you came being a div or pari or a jenn?” They will answer: “We are human beings.” Then, the elder monk will say: “Are you a slave or are you indebted toward someone?” They will reply: “No.” Then, the elder monk will say: “Are you dependent on or in the service of a king?” They will answer: “No.” Then, the elder monk will ask: “Are you blind, or deaf, or have any major disease?” They will reply: “No.” Then, the elder monk will say: “Did your father, mother, son, and wife consent to allow you to become monk or did you come here without their approval?” They will answer: “We came with their consent and approval.” Then, the elder monk will ask: “Do you have relations with other people?” They will answer: “No.” Then, the elder monk will say that great and small will behave with one another according to their rank. They will answer: “Of course!” Then, the elder monk recites this formula to those same four people and they repeat it to him:

He recites it three times with rice in his hand. He recites it three times [on?] the garment that the monks wear on their shoulder. He recites the second spell seven times holding a razor in his hand and moves it under [their] ear lobe. After that, he will say the ten formulas that are recited when one becomes a Magh.chakādātā dukhāni saranthāyāni bān sācheh chi kartān thāyā ay daʾin kāsā dāʾin bhi tu apeh pājaʾi thāli nahi thi halā kisā nakhā daʾin dātājeh.Footnote 33

-

[11] The copy of The Customs of the Magh was completed on the eighteenth day of the month of Shawwāl of the Hijri year 1210, which corresponds to 1796 of the English, on a Wednesday.