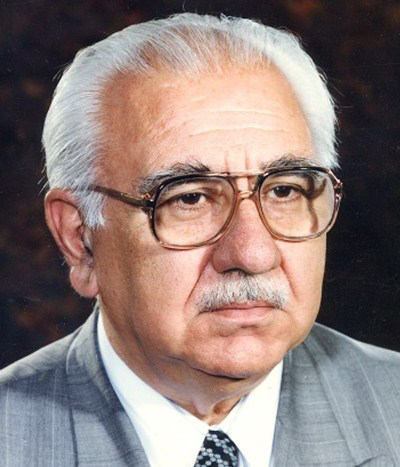

On 23 January 2017, renowned Georgian scholar of Iran, Doctor of Philology (Dr. Habilitatus), professor and author of over 200 scholarly publications in Russian, Georgian, Persian and other languages, Jamshid Shalvovich Giunashvili, passed away at the age of eighty-five. To lose a colleague is a blow in itself, but Dr. Giunashvili was also the last living representative of a golden age of outstanding Iran scholars from Georgia, which has produced experts on Iran of a caliber far out of proportion to its size.

Giunashvili's academic forebears and teachers were exponents of the older European Orientalist tradition in all its erudition and antiquarianism. Justin Abuladze (1874‒1962), one of the founders of the Georgian Orientalist school, had studied in St. Petersburg and conducted research in the libraries of Vienna and Paris. Georgian Orientalism in the twentieth century developed a strong reputation for philology, manuscript studies and—in large part thanks to Giunashvili—linguistics, and kept its distance from the “Red Orientalism” that took root in Moscow. While most of Giunashvili’s colleagues approached their subject through philological studies in Leningrad, Giunashvili himself came to know and love Iran by growing up there, spending his formative years in a nexus of several cultures. “I am an imported fruit,” he joked in an interview in Georgia later in life.Footnote 1 A recognized authority among Soviet Orientalists, Dr. Giunashvili was often called “a living encyclopedia” of Iran. Russian Iran scholar Yury Rubinchik dubbed him “the maestro” for his brilliant Persian.Footnote 2 Giunashvili leaves us a wide-ranging scholarly legacy that covers linguistics, literary criticism, manuscripts, historical source studies, anthologies and dictionaries.

No account of Jamshid Giunashvili's scholarly biography should be shorn of the context of his family biography, the contours of which resonate with the fates of many other Georgian intellectuals caught up in the turbulence of the times. Jamshid's father, Shalva Giunashvili (1908‒81), was the son of a priest who tended a church in the Kakheti Region of Georgia. Shalva eventually became an engineer, and his brother Giorgi graduated from Warsaw University to become a prominent physician. Jamshid’s uncle was politically active, however, and he was executed for supporting and providing medical assistance to an anti-Soviet uprising in 1924, led by guerilla leader Kaikhosro “Kakutsa” Cholokashvili. Giorgi's fate cast a long shadow, which would have both benefits and costs for the future scholar.

In 1928, Shalva Giunashvili was sent to Turkmenistan to work on irrigation projects. From there he slipped into Iran—knowing not a word of Persian. The Iranian border patrol promptly seized the illegal alien and dispatched him to a camp in Zahedan on the border with what was then India, whither he was to be deported. But here destiny smiled on Shalva: the local governor turned out to have been a classmate of his executed brother and had repeatedly been a guest in the home of the Giunashvili family. Expulsion to India thus avoided, Shalva was instead transferred to Tehran and soon freed. In the capital, he encountered another link from home: Elena Guliverdashvili. Elena had attended a school for girls in the small city of Telavi in Kakheti, where Shalva had studied in a theological seminary prior to his engineering training.Footnote 3 They married and started a family. Shalva Giunashvili's engineering knowledge proved to be in high demand during the railway construction boom in Iran in the 1930s, and he was able to provide for a comfortable existence.

Thus Jamshid Giunashvili was born in Tehran, on 1 May 1931. He attended the “Alborz” High School (formerly the American College) in Tehran, where he distinguished himself as an outstanding student of Persian. Thanks to his parents' efforts, Jamshid also acquired fluent Georgian and Russian from childhood. Their home was filled with books in Georgian and Russian published by émigrés in Paris and sent to Tehran. In free time away from school, Jamshid interacted with Russian-speaking émigrés—Russians, Georgians and Armenians. The family's attitude toward the Soviet Union must have changed with time. In 1942, Jamshid became a member of the Soviet club recently opened in Tehran.Footnote 4 The homeland was clearly exerting its pull.

In November of 1947, the entire family—Shalva and Elena Giunashvili and Jamshid and his younger brother—was granted Soviet citizenship and repatriated. In Georgia, Jamshid graduated from a Russian school and was accepted into the Department of Oriental Studies at Tbilisi State University. But the homecoming was to be short-lived. In 1952, in the middle of his third year at university, Jamshid and his family were deported to southern Kazakhstan. This was a time when even those who had voluntarily re-immigrated to Georgia—“former wanderers outside the fence”—were suspected of ties to outside intelligence agencies, and only a few shades of suspicion away from those who had fought Soviet power, fled or refused to return.Footnote 5

From the “periphery” of rural Kazakhstan, where the authorities hoped the Giunashvilis would have little to no interaction with Soviet centers or foreigners, Jamshid posted a letter to the rector of Tbilisi State University, Professor Niko Ketskhoveli, requesting his academic transcript and high school diploma. A month later, the records of his excellent academic performance arrived. Giunashvili now put his plan into action, stealing away on a freight train headed to Tashkent, where he met with the dean of the Faculty of Oriental Studies at the University of Central Asia, Gregory Lvovich Bondarevsky, who was willing to take a risk in helping the aspiring scholar and confident that Giunashvili could cover four years of requirements in only one; he therefore encouraged Giunashvili to try to earn his diploma as soon as 1953. The only stipulation was that for the time being nobody should see him on campus—as an internal deportee, Giunashvili was not permitted to leave Kazakhstan. But Stalin's death changed the prevailing atmosphere and Giunashvili's deportee status was soon lifted. He officially became a Ph.D. student and then a lecturer at the university.Footnote 6

In 1956 in Tashkent, he began his Ph.D. thesis on “The Verbal Component of Determinative Nominal Forms in Literary Persian.” Soviet Iranian studies at the time could boast many scholars of literature, but despite a few key figures, there were far fewer linguists. The young scholar's natural aptitude for and interest in detailed linguistic analysis would be a major force in broadening the spectrum. In 1957‒58, Giunashvili published his first scholarly works, which were listed in a bibliography of noteworthy publications in The Middle East Journal.Footnote 7

Having experienced his share of the negative side of Soviet life, Giunashvili would also benefit from the largesse of the Soviet government in supporting scholarship. In 1958, he made his second “return” to Georgia from exile, this time at the invitation of the prominent Georgian Orientalist Giorgi Tsereteli. Giunashvili immediately began working as a researcher in the Department of Middle Eastern Languages at the Georgian Institute of Linguistics; and the same year, at Tbilisi State University, he defended the Ph.D. thesis he had written in Tashkent. Giunashvili had also married in Tashkent. His wife, Lyudmila Semyonovna—née Myrina—had to stay behind for a year in order to graduate from the University of Central Asia, but she joined her husband in 1959.Footnote 8

In 1960, a Georgian Institute of Oriental Studies was created under the aegis of the Georgian Academy of Sciences. The institute had a Department of Persian Philology, and Persian was also studied within the institute's Department of Indo-European Languages. These, combined with Tbilisi State University's Department of Persian Philology, made for three departments in Tbilisi offering advanced studies of the Persian language—a testament to the importance of Iran, and of Persian philology in particular, in Georgian humanities. At the new institute, Giunashvili soon became head of the Department of Indo-Iranian Languages and, in 1974, deputy director of the institute (a post he retained until 1994, when he was appointed ambassador to Iran). At the same time, he taught as a professor in the School of Oriental Studies at Tbilisi State University.

From 1960 onward, his contributions appeared regularly in The Proceedings of Tbilisi State University and publications of the Academy of Sciences of Georgia. The study of manuscripts was also an area of keen interest for the rising scholar, and Georgia's rich fund provided ample opportunity. Rediscovered manuscripts in Georgian archives allowed Giunashvili to decipher opaque passages in The History of Sistan that had eluded earlier scholars. This work eventually led to Giunashvili's publication of an authoritative text in Persian in 1971.

In 1964, Giunashvili collaborated with Georgian linguist Shota Gaprindashvili, then head of the Experimental Linguistics Laboratory at the Institute of Linguistics of the Georgian Academy of Sciences, on the book The Phonetics of the Persian Language.Footnote 9 The two scholars became the first to carry out a detailed x-ray, oscilloscopic and spectrographic study of the phonetics of standard Persian. The work, with its interdisciplinary use of technology and an anthropological approach, was received enthusiastically and became an instant classic widely referenced in the Soviet Union and elsewhere. Professor Vladimir Ivanov, now head of the Department of Iranian Philology at Moscow State University, says of the book—which has stayed on his desk since his student days:

Even to this day, no one has performed such a detailed examination … Jamshid Shalvovich not only recorded speech, he evaluated the accepted theories and framework at the time for understanding the Persian language. With this book, he overturned several positions then current on Persian phonetics and provided material evidence for his divergence from what had been thought before. I want to emphasize that previous studies had not been conducted using a scientific experimental approach. They had relied on the ear, while Giunashvili employed x-ray imaging.Footnote 10

The following year, Giunashvili published a fifty-five-page addendum, “The System of Phonemes of the Persian Language,” in The Proceedings of Tbilisi State University, which again met with positive reviews at home and outside the Soviet Union.Footnote 11 In 1966, at the relatively young age of thirty-five, Giunashvili defended his habilitation thesis and was awarded a Doctorate of Science in Philology. In the 1970s, Giunashvili fulfilled earlier plans to produce two dictionaries: A Georgian‒Persian and Persian‒Georgian Pocket Dictionary (1971) and A Compact Russo-Persian Technical Dictionary (1974), the latter becoming the primary reference in the USSR for specialized terminology in Persian.

Numerous studies on various aspects of Persian vocabulary, terminology, textual criticism and source studies belong to the pen of Giunashvili, a testament to the breadth of his interests. A growing and important theme in his work was the influence of Persian literature on Georgia. Giunashvili closely followed publications by and about Georgian Iranian studies scholars, and he himself published a number of works on Georgian Iranian studies in Persian. He devoted special effort to developing a variety of materials for Persian language learners, preparing an anthology of historical texts and textbooks for university and elementary school students (there was an elementary school in Tbilisi where Persian was studied in the youngest grades). A large portion of his work examined the Fereydan Georgians, a group of ethnic Georgians in Iran, and their dialect, strongly influenced by Persian. He gathered comparative linguistic samples in order to analyze how the original Kakhetian Georgian dialect of the Fereydan Georgians was altered by exposure to Persian.

Giunashvili was an active participant in scholarly gatherings and never failed to command a lively interest among his audience when he spoke. The most productive period of his career spanned the 1960s to the first half of the 1980s, when he was publishing groundbreaking works on Iranian linguistics, lexicography, textual criticism, literary criticism, source study and even different aspects of Iranian history through the prism of lexica. In the 1990s, however, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, which brought freedom but took away the massive academic support apparatus that had been especially beneficial to the smaller republics, the scholar's research output diminished. Aside from the rare academic work, Giunashvili published mostly journalistic pieces in the Georgian media offering subjective views on modern Iranian history. He worked more as a popularizer and promoter of Iran, something undoubtedly connected to his tenure as Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Iran from 1994 to 2004 (the first ambassador from independent Georgia to Iran) but also to the general deterioration of scholarship in Georgia, now free of the old ideological shackles yet bereft of financing and faced with new problems. The Institute of Oriental Studies of the Georgian Academy of Sciences, whose founding had helped to spur Giunashvili's rise as a scholar, was merged with Ilya State University—which had no history of teaching Eastern languages—and thus greatly diminished; while at Tbilisi State University, the School of Oriental Studies was eliminated, although Eastern Studies are still offered within the Humanities Department.

With Jamshid Giunashvili’s passing, we not only bid farewell to a unique individual and irreplaceable scholar, but to one of the last representatives of a difficult yet exceedingly rich exceedingly rich intellectual epoch in the history of Georgia.