At Persepolis, 2005

Italian Iranologist Gianroberto Scarcia left us on the first day of July 2018. He was a great scholar of Iran and beyond, devoting himself to the study of Persian culture and literature and producing a truly remarkable number of works, which essentially touched upon all fundamental cultural expressions of that vast and articulated world.

Gianroberto Scarcia was born in Rome on 11 March 1933, and, after attending the Liceo Classico Ennio Quirino Visconti, he enrolled in the Faculty of Law at the La Sapienza University of Rome. During this period, he began studying the Persian language under the guidance of Alessandro Bausani (1921–88), who was at the time a teacher of Persian at the Institute for the Middle and Far East (IsMEO, which later became IsIAO following the merger with the Italian–African Institute). In those years Scarcia perfected his knowledge of Persian after being awarded a scholarship for foreign students at the University of Tehran, financed by the Iranian government. He graduated cum laude in the summer of 1955, with a thesis dedicated to uṣūl in the jurisprudence of Jaʿfarī madhhab. Part of the results of his research merged into an important essay entitled “Intorno alle controversie tra Ahbārī e Uṣūlī presso gli Imāmiti di Persia” (On the disputes between Akhbārī and Uṣūlī within the Imāmites of Persia), that was published in Rivista degli Studi Orientali (33, no. 3–4, 1958, pp. 211–50), where the author must be given credit for having clearly identified what would only later become the main lines of inquiry in the field of legal studies relating to the Twelver Shiʿite world. In that same year, he also published an article dedicated to “Stato e dottrine attuali della setta sciita imamita degli Shaikhī in Persia” (Conditions and current doctrines of the Shiite Imamite sect of the Shaykhīs in Persia), which appeared in Studi e Materiali di Storia delle Religioni (29, 1958, pp. 215–41). Many years later, his research in this area of knowledge in the Muslim world became the stepping stone for his wide-ranging study, entitled Ripensare la Creazione: Il metodo del giurista islamico (Rethinking creation: the method of the Muslim jurist, Rome: Jouvence, 2001).

After graduation, Gianroberto Scarcia, with the plaudit and advice of Alessandro Bausani—who, as he would describe later, considered Scarcia a friend and a colleague with whom to dialogue and discuss, rather than as a student stricto sensu—devoted himself intensely to Islamic and Iranian studies (Per l’Undici di Marzo—Quaderni del seminario di Iranistica, Uralo-Altaistica e Caucasologia dell’Università degli Studi di Venezia, no. 21, Venice: La Tipografica, 1983). Thence, a rapid and brilliant career led him first to a job as librarian at the prestigious Fondo Caetani of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei—Italy’s Academy of Science—and, later (1967–98), to the position of Professor of Iranian Language and Literature and of History of Religions of Iran and Central Asia at the University of Venice Ca’ Foscari, where he was elected Dean of the Faculty of Foreign Languages and Literature for the four-year period 1973–76. In 1970 he also won a competition for a Chair in Islamic Studies at the University La Sapienza of Rome. In the years 1998–2008 he held the position of full Professor of the History of Arab-Islamic civilization at the University of Venice Ca’ Foscari, eventually receiving the title of Emeritus Professor.

The field in which Scarcia is perhaps best known is that of translation of poetry from the main languages of the Islamic world and from Persian in particular (see the very recent publication of his Divano Occidentale, Rome: Viella, 2017). Persian literature and its lyrical aspects is a passion which accompanied him throughout his life and which he formulated precociously in his work by engaging with the epistemological question imbued in the challenge of translation. His numerous publications bear witness to his engagement in this area, starting from a study dedicated to Ṣādeq Hedāyat “«Ḥağī Āqā» e «Būf-e kūr», i cosiddetti due aspetti dell’opera dello scrittore contemporaneo persiano Ṣādeq Hedāyat” (Ḥağī Āqā and Būf-e kūr, the so-called two aspects of the work of the contemporary Persian writer Ṣādeq Hedāyat) that was published in Annali dell’Istituto Universitario Orientale di Napoli (n.s. 8, 1958, pp. 103–23). Already in 1970 he had developed the Italian rendition of all the literary pieces cited in the Storia della Letteratura Persiana edited by A. Piemontese (Milan: Fratelli Fabbri, 1970). After a vast and varied scholarly production, part of which was merged into various numbers of the prestigious Italian magazine In forma di parole (In the form of words), in 2005, in collaboration with S. Pellò, he finalized a complete translation of Hāfez’s Divān (Milan: Ariele, 2006). This magnum opus bears the fruit of Scarcia’s epistemological reflection upon the intimate encounter—in the realm of sentient and ideal things—in poetic territories, borderless and intersubjective. Here, transposed in Italian language, Hāfez’s poesies encounter the sensual mysticism of Francesco Petrarca, the early Renaissance poet.

The way in which Gianroberto Scarcia looks at Persian poetry is not exclusivist. His approach travels beyond the contours, however ambiguous and transient, of what is classically conceived as expressed in Persian; it concentrates rather on the aesthetic phenomenon of a literature deriving from the Persian literary model that finds its expression also in other languages of the Muslim world, such as Turkish (see, for example, his Storia della letteratura turca, Milan: Fratelli Fabbri, 1971) and Urdu (see, for instance, his essay “Letteratura persiana d’India e indostana” [Persian literature in India and Hidostani literature], which was published in L’Islam indiano, Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 1990, pp. 35–58), and “Tredici poesie di Naẓīr Akbarābādī” (Thirteen poems by Naẓīr Akbarābādī) in Ex Libris Franco Coslovi (Venice: Il Poligrafo, 1996, pp. 103–18), to name just a few of the languages he mastered and from which he translated.

Scarcia’s approach leads us to the discovery of a poetic universe characterized by a continuum in its forms—and mannerisms—with that of the aesthetics of the Mediterranean tradition in late antiquity. Conveyed by Islam, which constituted the propelling factor, and mainly by a language, Persian, which was its main literary medium—this aesthetic and literary form has been able to reformulate itself over the centuries in a plurality of languages, to merge into what, according to Scarcia, are its main reference poles: the homoerotic canon of Greece; the Turkic world with its Sino-Mongol imagery; the Indian Persianate literature and the much closer experience of the Central Asian Soviet world. This extremely wide approach to the literary factor led him to translate also from other languages of Eurasia such as Russian, obtaining important recognitions including, in 2000, the National Award for Translation assigned to him by Italy’s Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities.

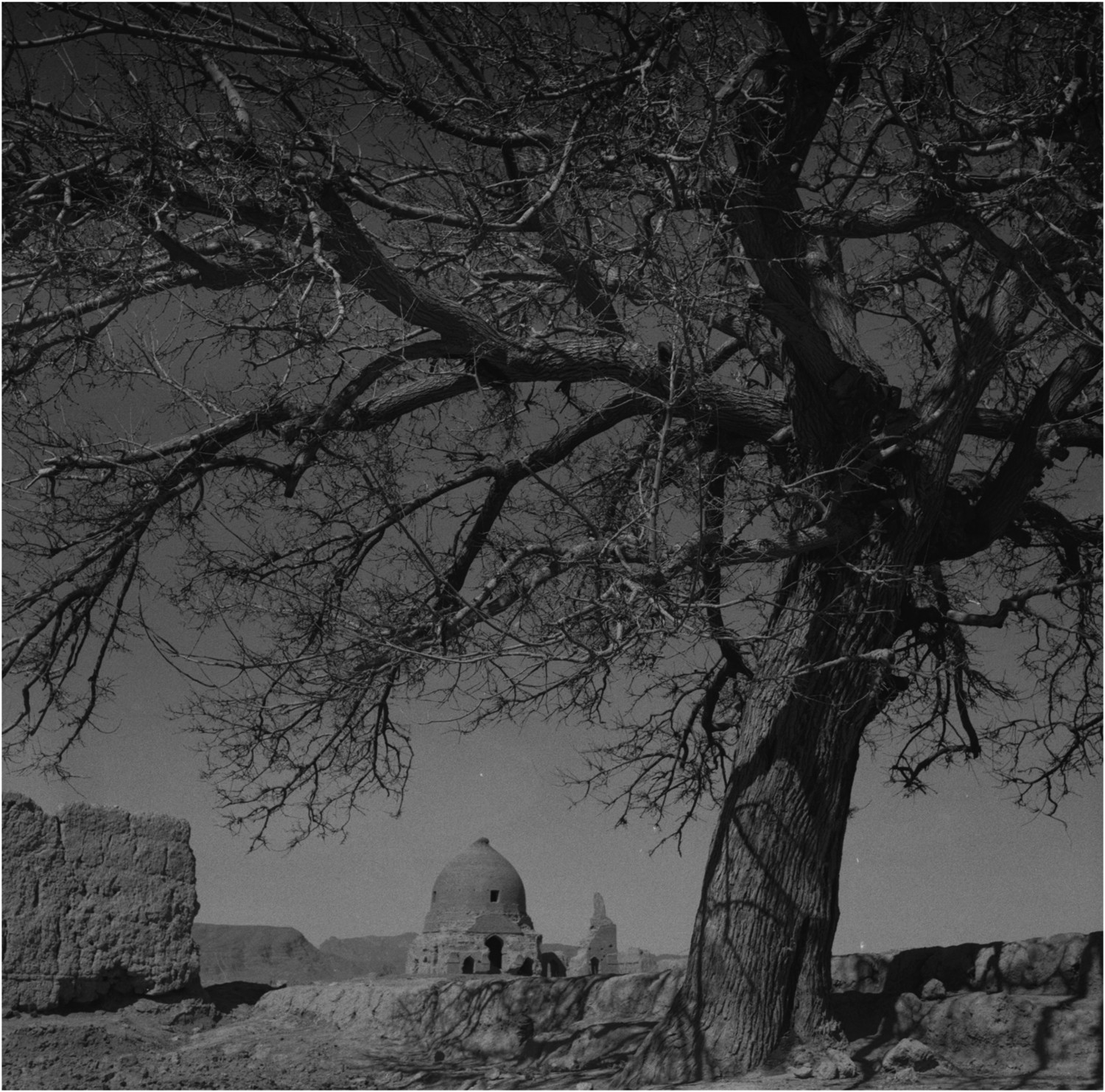

Scarcia’s interest in Persian literature and poetry was combined with an extremely refined sensitivity for the artistic phenomenon as a whole: architecture, painting, art history, and the overall aesthetics of the Persianate world. As Giovanni Curatola lucidly observed in his homage to Gianroberto Scarcia “Il giusrista e l’estetica” (The jurist and aesthetics) in L’Onagro Maestro (Venice: Cafoscarina, 2004, pp. 114–17), his intuitions, often far from jargon and technicalities which were instinctively alien to him, were dictated rather by the smooth and precise insertion of the observed object in an artistic perspective conscious of the Asian context, with an ability to see holistically the history and the taste, resulting from extraordinary knowledge and lucid analysis. The pages written by this eminent scholar are crammed with intuitions of this genre, often sown nonchalantly in a scattered fashion. And his many black and white photos from the 1950s and 1960s alone would be enough to do him justice as historian of Islamic architecture: his cut is always artistic, but every single frame is a declaration of how the monument was read in its entirety and understood in depth.

Figure 1. Kāj (Isfahan)—The Congregational Mosque.

Source: G. Scarcia archive.

Scarcia’s photography is one of the most important (and least known) chapters of his scientific production in the historical-artistic field. In an article on “Il paesaggio di Guillaume de Jerphanion” (The landscape of Guillaume de Jerphanion) in La Turquie de Guillame de Jerphanion S.J. (Actes du Colloque de Rome, 9–10 May 1997, réunis par Ph. Luisier, Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome 110, 1998, pp. 851–7), Scarcia labeled those photographs or photograms as rerum vulgarium fragmenta. These fragments of reality, after all, bear witness to an aesthetic actuality that was congenial to him as a literary scholar and translator—because, in his opinion, “the photographer’s affinity with the man of letters is perhaps greater than with the painter” (Il paesaggio di Guillaume de Jerphanion). A passion fueled by a tireless attitude to travel led Gianroberto to explore far and wide in much of Asia: it is a daunting task to find an Islamic monument (say, in Turkey or in Iran, but also in Central Asia, in Syria, in Egypt) that Gianroberto did not visit in person.

His gaze on the world through the photographic lens translated into sharp images which distinguished between what stood before and after the encounter with the object of inquiry, following an order that was already very clear to him by the end of the 1950s, a period of discovery of the beloved country. Here, in his words,

the camera is the mechanical instrument which, by too easy a definition, should always be truthful. Instead, it must pursue, for its technical unavoidability and according to a more intimate and cogent definition, a harmony which would be superfluous to a sketch drawing. Said harmony, however, must appertain—lest the photographer incur in an infidelity both intolerable and proscribed —to the object portrayed and to what is possible to see as its legitimate, exclusive core … And here the photographer mimics in his work the translator; he transmutes from a homogenous means to a homogenous means (from ear to ear, rather than from eye to eye), while ordering and creating hierarchies among the elements that he set out to transmit. (Il paesaggio di Guillaume de Jerphanion, p. 855)

Beyond the exquisitely aesthetic drive of Scarcia’s way of looking at the world, his photographic work has an undeniable value as historical testimony, as confirmed by his photography of the Seljuk mosque in the city of Damāvand, radically and irreparably remodeled by the pietas of devoted local patrons; the framework of the case is found in his article “Sulla distrutta moschea di Damāvand” (On the destroyed mosque of Damāvand), published in Annali di Ca’ Foscari (9, no. 3, Serie Orientale 2, pp. 135–7 + 4 tables.).

Although it is not our intention to outline here a complete profile of the figure of this great Italian scholar and intellectual,Footnote 1 we must mention his very important production in the field of the history of religions, a field that has seen the last monograph by Gianroberto Scarcia published in his lifetime. This book is dedicated to the materials that can be found in the Arab-Persian and Eastern-Christian literary, cultic and artistic traditions regarding the Seven Sleepers (see Nelle terre dei (Sette) Dormienti. Sopralluoghi, appunti, spunti, Perugia: Graphe.it, 2018).

Scarcia’s interest in this field dates back to his early years as a researcher—in 1958 he made a methodological contribution on “Iran ed eresia musulmana nel pensiero del Corbin (Spunti di una polemica sul metodo)” (Iran and Muslim heresy in Corbin’s thought (Sketches of a polemic on method), published in Studi e Materiali di Storia delle Religioni (29, pp. 112–27), and a review of E. A. Beljaev, Musul’manskoe Sektanstvo (Islamic sects) (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo vostočnoj literatury, 1957), published in Annali dell’Istituto Universitario Orientale di Napoli (Nuova Serie, vol. 8, pp. 213–16).

In 1962 Scarcia translated one of the most significant works of R. C. Zaehner, The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism, released in London in 1961 and published with the Italian title of Zoroastro e la fantasia religiosa (Milan: il Saggiatore), which brought him closer to the main problems posed by the reconstruction of the religious history of the Iranian world with a particular focus on what historically pertains to the eastern Iranian world, from the Sistanic kharijism to the nature of the so-called kafiri religion, from the reconstruction of the “religion of Zabul” to the historical-religious problem of the Zunbīl. In the 1970s and 1990s his perspective widened considerably, focusing on the phenomena of the encounter, sharing and passage between the eastern Christian world and Islam (see for example “Bastām e la stirpe dei draghi” [Bastām and the ancestry of dragons], in Transcaucasica II, Quaderni del seminario di Iranistica, Uralo-Altaistica e Caucasologia dell’Università degli Studi di Venezia, 7, Venice, pp. 82–107, and “Vent’anni di ricerche sui Magi evangelici” [Twenty years of research on Evangelical Mages], in Venezia e l’Oriente, edited by L. Lanciotti, Florence: Olschki, 1987, pp. 273–86).Footnote 2

Gianroberto Scarcia’s contribution to the study and understanding of the Islamic civilization—and of its encounters with the Mediterranean world—is colossal. Yet this monumental body of knowledge is also a nomadic science, moving across, transiting between, connecting, merging and setting free the historical and the humanistic cosmologies of East and West. Its legacy is a school that knows no frontier. After all, many in Iran and beyond remember him as Jānrobā-ye Shekārchi.