Introduction

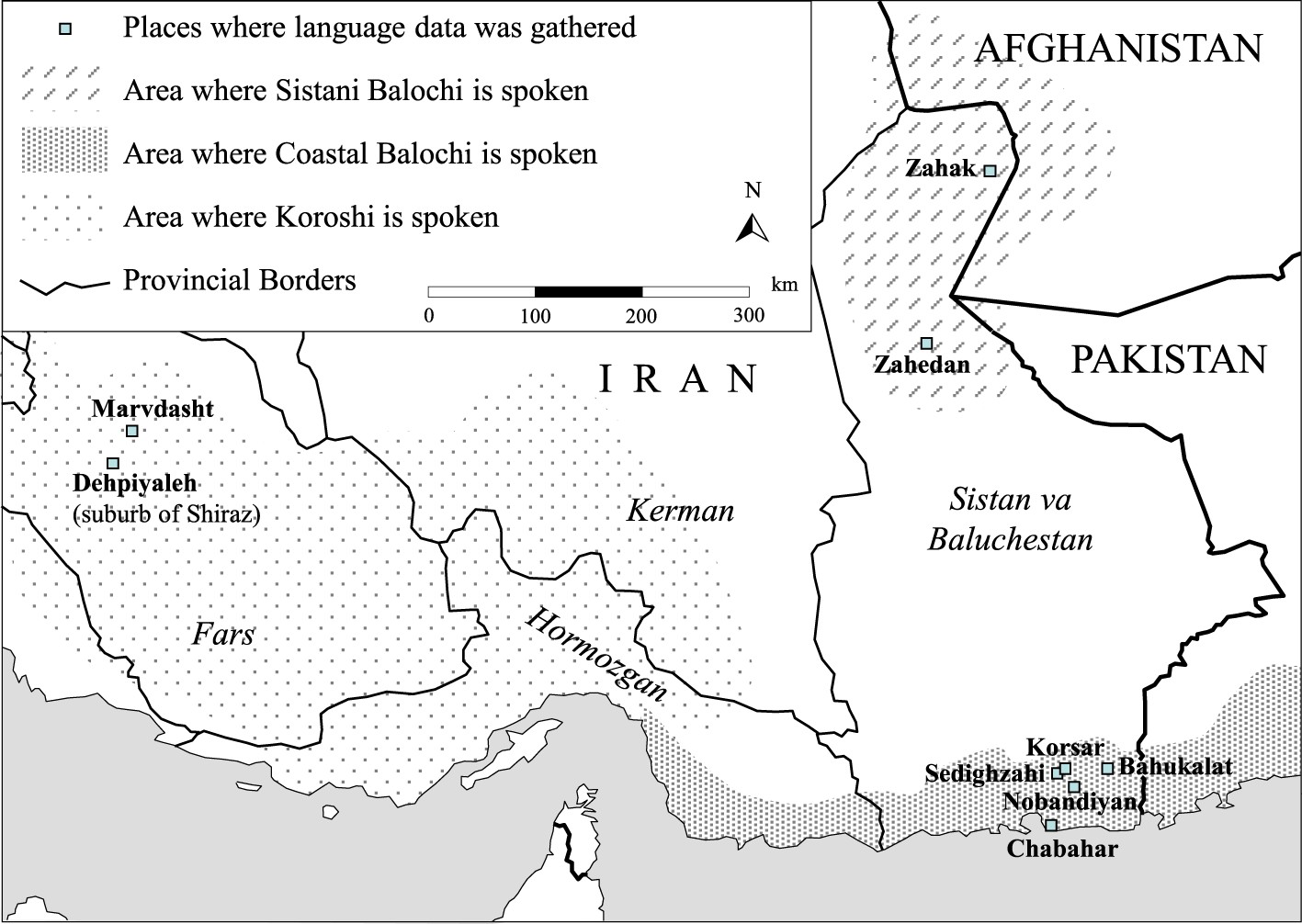

Balochi is a term for a collection of closely related northwestern Iranian languages spoken across a large region of eastern Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, with outliers in southwestern Iran and Turkmenistan.Footnote 1 This paper deals with three major dialects: Sistani Balochi (SisBal), Coastal Balochi (CoaBal) and Koroshi Balochi (KorBal). The approximate locations of these three dialect groups is indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The approximate locations of these three dialect groups.

Source: Taken from Nourzaei, Participant Reference in Three Balochi Dialect, 31.

Across all dialects, a suffix of the form -ok/ak/ek/lok/o is attested, primarily occurring with nouns but also with adjectives in some dialects. It has traditionally been classified as a “diminutive,” and is presumably cognate with a number of formatives containing a velar plosive [k], or reflex thereof, in other Iranian languages, and in Indo-Aryan. The original function of this suffix has yet to be established with certainty, but available accounts suggest a high degree of multifunctionality. There is often a semantic component “less than expected size,” but more frequently we find an evaluative component, expressing the speaker's empathy, familiarity and endearment, or conversely, disdain with respect to the diminutive-marked noun. Such evaluative connotations are cross-linguistically widely attested.Footnote 2 Given the salience of the evaluative components (and the lack of any reference to “size” in many contexts, see below), we follow Pakendorf and Krivoshapkina in referring to the function of this morphology as evaluative, rather than diminutive.Footnote 3 We follow Haig in referring collectively to the variants of the relevant suffixes in Balochi as K-suffixes.Footnote 4

The focus of this paper is what we term the definitizing function of K-suffixes in Balochi. It can be shown that in at least one dialect of Balochi, the K-suffix is systematically associated with definiteness, in a manner approximately comparable to better-researched definite articles of the languages of Europe, e.g. English. Given that almost all the previous literature on the history of definiteness marking assumes an origin from a demonstrative (see below), the Balochi definiteness marker has considerable implications for our understanding of definiteness systems and their emergence. For even though the precise function of the ancestor of Balochi—ok/ak/ek/lok/o—remains obscure, it can be stated with some certainty that it is not related to a demonstrative element. The Balochi case thus joins the small minority of definiteness markers with non-demonstrative origins, for example Ėven (Tungusic, Mongolia), discussed in Pakendorf and Krivoshapkina.Footnote 5

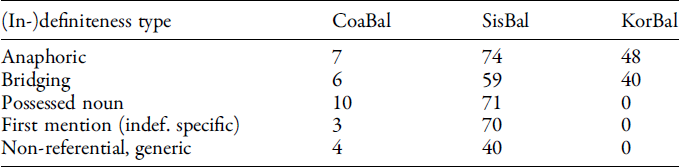

There is little previous research on (in-)definiteness in west Iranian languages.Footnote 6 The data for this study stem from an extensive corpus of spoken Balochi narratives from the three dialects, namely KorBal, CoaBal and SisBal, containing a total of 31,439, 47,889 and 12,877 words respectively (see Table 1 for an overview). We complement the quantitative data with a qualitative approach, illustrating the various functions with authentic examples and appropriate reference to context. We also make reference to the results of a questionnaire-based survey with Balochi speakers, based on the questionnaire used for Kurdish in Haig.Footnote 7

One of the most striking aspects of the narrative data is the high degree of inter-speaker and inter-text variability in the KorBal corpus. The definiteness function of the K-suffix in this dialect is systematically documented for very few, female speakers. This contrasts with the findings from the questionnaires, which exhibit a high degree of cross-speaker conformity and systematicity of the definiteness usage. We surmise that this situation may arise through very recent changes, affecting initially few speakers and non-traditional genres. In the narratives, on the other hand, many of which express traditionally transmitted, culturally emblematic content, these changes are not actualized, though this interpretation remains speculative.

Overall, the data do not lend themselves to interpretation in terms of a gradual continuum of grammaticalization of the kind commonly predicted for the emergence of definiteness marking.Footnote 8 Rather, the development appears to be fairly erratic, and sensitive to speech context (genre, speaker gender) rather than linguistic context. Given that the usage of evaluative morphology is, by definition, primarily determined by interactional context, this outcome is not surprising. We will also consider the possible role of language contact in shaping the outcome in Koroshi, and contrast the overall findings with received wisdom on the grammaticalization of definiteness.

The paper is organized as follows. First it deals with definiteness and types of definiteness contexts, followed by an overview of the Balochi language. Then it covers previous studies on the K-suffix in Balochi and illustrates the multifunctionality of the K-suffix. Subsequently, the evaluative function of K-suffixes in Coastal and Sistani Balochi are described, and then K-suffixes as definiteness markers in Koroshi dialect are demonstrated. Data is presented from an extensive text corpus, and from questionnaire data, and the findings are discussed in the light of a grammaticalization pathway from evaluative to definiteness marking.

Definiteness

Definiteness is defined here as a property of noun phrases that derives from their information status in a given linguistic context. We follow Lyons in considering the primary component of definiteness to be the notion of identifiability:Footnote 9 a noun phrase (NP) is considered definite if the speaker assumes that its referent is uniquely identifiable by the addressee. Languages differ in the extent, and in the means, by which they indicate definiteness systematically in morphosyntax. In English, French or Arabic, definiteness is marked fairly consistently through items generally referred to as “articles.” Other languages may mark definiteness by affixes, clitics, word-order properties or various combinations of these strategies, or they may have no regular means for indicating definiteness. A NP may have definite status by virtue of a number of possible contextual factors, which we broadly characterize as follows:Footnote 10

In contrast to the seven definiteness contexts outlined above, nouns may be indefinite (either specific or non-specific), or have generic or sortal reference. The correct analysis of generics is beyond the scope of this paper, but we note that in general, generic referents in Balochi are treated in a similar manner to non-specific indefinites, and we will not further distinguish them here.Footnote 12

The Balochi Language

Balochi belongs to the northwest Iranian branch of the Iranian languages, which belong to the Indo-Iranian branch of Indo-European. It is a verb-final language, but exhibits mixed adpositional typology (dialectally variable) as well as dialectally differentiated alignment systems (some version of ergativity in the past tenses in e.g. Coastal dialect, elsewhere accusative in e.g. Sistani Balochi dialect). It has three main dialects: Southern, Eastern and Western Balochi. Each of these dialects presents its own sub-divisions.Footnote 13 Balochi is mostly spoken in southeastern Iran and southwestern Pakistan, and also in Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Oman and the UAE. The area where Balochi is spoken is linguistically highly diverse, and almost all Balochi speakers are multilingual. Contact languages include four different language families, and different genera: Indo-European (Indo-Aryan and Iranian), Dravidian, Turkic and Semitic. The total number of Balochi speakers is uncertain. However, Jahani reports that the number of Balochi speakers is estimated as at least 10 million speakers.Footnote 14

The map in Figure 1 presents the location of the three dialects Coastal, Koroshi and Sistani Balochi.

The K-Suffix in Balochi: Initial Observations

Across Balochi a nominal suffix is found with the form -ok/ak/ek/lok/o. We assume that they are all reflexes of a middle-western Iranian suffix involving a final-K, but with differing vowel values according to the nature of the nominal stem to which it attached in Middle Iranian.Footnote 15 It is traditionally referred to as a “diminutive.” Jahani and Korn report that “The suffixes -ik(k), -uk, and -luk (to a certain extent also -ak(k) (also) have a diminutive function;Footnote 16 -uk is particularly productive also on names,”Footnote 17 However, Nourzaei and colleagues already point to a definiteness effect associated with this suffix in KorBal, to which we return below.Footnote 18

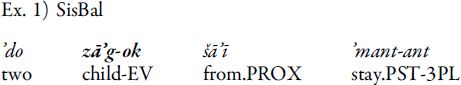

The term “diminutive” implies a descriptive content of “smaller than normally expected,” and this is evident in some usages of K-suffixes. However, even in these contexts, an evaluative connotation is often discernible, and we have therefore opted to gloss the suffix with ev, as the most general indication of function, regardless of actual context. Initial exemplification is provided from Sistani Balochi (SisBal). In example 1, the K-suffix adds a flavor of sorrow on the part of the speaker regarding the fate of the orphaned children, while in example 2, the speaker emphasizes her disapproval at the lack of respect on the part of the girl, who fails to give even a small bowl of water to her own mother:

“she [died and] left two small children [in this world]”Footnote 19

“this girl did not give her mother even a small bowl of water”Footnote 20

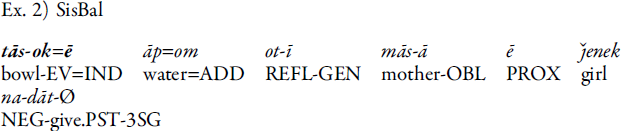

The evaluative component is more obvious in the following examples, where a mother refers to her daughter with a K-suffix, although the daughter is an adult married woman with two children of her own. This is obviously a signal of endearment and affection on the part of the speaker towards the daughter, rather than a description of physical size of the daughter:

“my lovely daughter came from Zahedan last night”Footnote 21

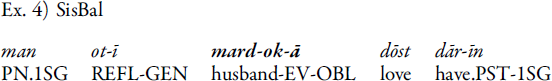

Example 4 is from a dialogue between a father and his daughter. The father attempts to persuade the girl to stay with him rather than follow her husband. The daughter rejects her father’s suggestion, and uses the K-suffix in referring to her husband, underscoring her affection towards him, with no connotation of small size involved:

“I love my dear husband”Footnote 22

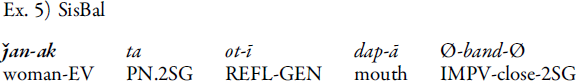

K-suffixes also occur with pejorative connotations. This can be observed in vocative contexts such as in example 5, taken from a dispute between a man and his wife. Here the K-suffix reflects his anger and disapproval towards his wife in the given context:

“woman shut up (lit. close your mouth)”Footnote 23

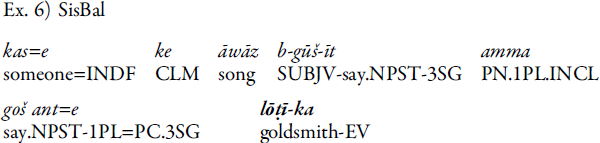

Example 6 is taken from a conversation with a Baloch speaker from Sistan. I had asked her to sing a folksong for recording, but she declined my request. In this context she uses the K-suffix to convey her negative attitude towards singing performances.

“whoever sings we call him/her lōṭī-ka”

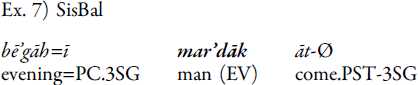

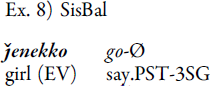

Finally, we should point out that there are certain words, typically indicating human referents, which seem to include the K-suffix as part of the word stem, e.g. ǰanak, “the woman,” mardak “the man,” ǰenekkō “the girl,” čorī”ka “the boy.” The suffix lacks any obvious semantic content. This is particularly frequent in Coastal Balochi.

“in the evening, the man returned back”Footnote 24

“the girl said”Footnote 25

“the wedding celebration of the man started”Footnote 26

This echoes similar developments in Middle West Iranian, where a high proportion of the nominal lexicon carries a semantically redundant reflex of a K-suffix.

In sum, the K-suffixes of Balochi are widely attested with some kind of evaluative semantics, but also as lexicalized and semantically empty elements, presumably remnants of high-frequency evaluative usage associated with certain words. We assume that the multifunctionality of the K-suffix is reasonably representative of earlier stages of Balochi, and is also compatible with what is known regarding K-suffixes in earlier stages of Iranian. However, in the three modern dialects of Balochi under investigation here, the functionality and frequency of K-suffixes have diverged quite considerably. In particular, the Koroshi dialect now exhibits quite regular marking of definiteness. We begin with an outline of K-suffixes in Coastal and Sistani dialects, before focusing on the definiteness marking usage in Koroshi Balochi, and then presenting frequency data from the corpora.

Coastal Balochi

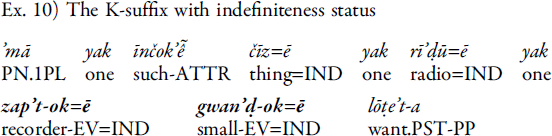

The data for this section is from eight spoken texts.Footnote 27 The K-suffix is attested with nouns, adjectives, adverbs and even a question word “četawrokā “what.” Functionally, it is generally confined to diminutive and evaluative contexts. It is also clearly compatible with indefiniteness status, as in example 10:

“we asked (lit. have asked) for something, a radio, a small recorder”Footnote 28

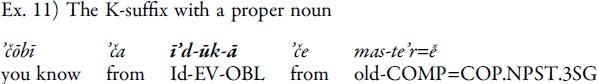

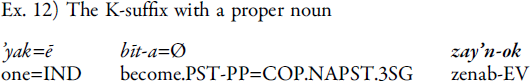

Examples 11–12 show the K-suffix is compatible with proper nouns, for example the person names “ī'dūk” and “zay'n-ok.” The frequency of the K-suffix with proper nouns is relatively high in this dialect. Note that it is not at all evident what the semantic content of the K-suffix in these contexts are; they appear to be relatively vacuous.

“you know, he was older than Ido”Footnote 29

“one called (lit. has been) Zenab”Footnote 30

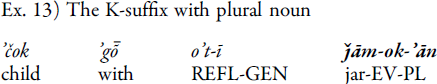

In CoaBal, there is no constraint against combining the K-suffix with the plural suffix (see below on this point). The following example illustrates a K-suffix with diminutive sense, followed by a plural marker.

“the children with their little jars…”Footnote 31

There are words where the K-suffix appears to have been reanalyzed as part of word stem, as in mardek “man,” lankok “finger,” čīpok “chick,” etc (see examples 7–9).

To sum up, the K-suffix in CoaBal lacks any obvious unified semantics, either evaluative or descriptive, and is not subject to structural constraints such as those that obtain for Koroshi Balochi. It rather resembles a sporadic remnant of now defunct morphology, which appears to have been incorporated into some items without any discernible change in meaning.

Sistani Balochi

Sistani Balochi (SisBal) is quite similar to CoaBal in that the K-suffix has a variety of functions, with few obvious structural constraints. However, there is one type of context that distinguishes SisBal from CoaBal, namely the combination of proximal demonstrative and K-suffix. The examples for this section are taken from Nourzaei and Barjasteh Delforooz’s studies.Footnote 32

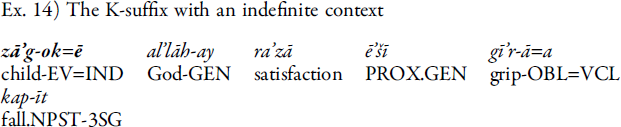

As in CoaBal, the K-suffix in SisBal is compatible with indefinite contexts:

“by God’s power; she found a little boy”Footnote 33

“he had a little donkey”Footnote 34

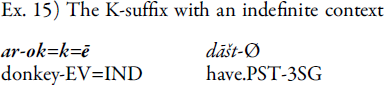

Unlike CoaBal, the SisBal corpus only contains a single example of the K-suffix with proper names, shown in example 16. However, in their daily speech, people frequently use the K-suffix with the proper nouns, e.g. tāǰ-ok “taj,” azīm-ok “azīm,” etc. The lack of such examples in the corpus is probably indicative of the strongly interactional nature of the K-suffix in SisBal, to which we return later.

“snake has beaten (lit. eaten) Khanbibi”Footnote 35

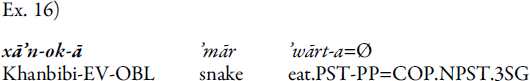

As in CoaBal, there is no restriction with the K-suffix in relation to the plural marker.

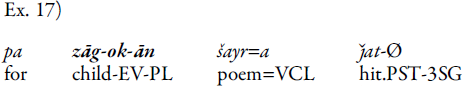

“he started reciting poems for the children”Footnote 36

K-suffixes as signals of proximity and mutual knowledge

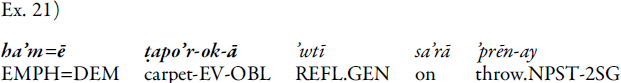

In SisBal, K-suffixes occur in what I will refer to as contexts of proximity, and mutual knowledge. Under “proximity,” I refer to contexts in which the referent concerned is an item in the immediate perceptual range of the interlocutors, and consequently will often be accompanied by a proximate demonstrative. Thus, we have the combination of proximate demonstrative determining a noun carrying a K-suffix as in examples 18–22:

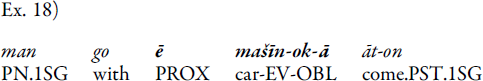

“I came with this car”Footnote 37

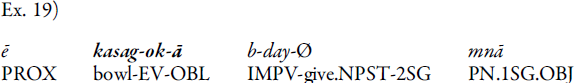

“give me this bowl”Footnote 38

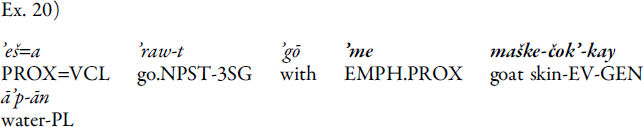

“He went with this water in the goat skin”Footnote 39

“you cover yourself with this carpet”Footnote 40

“[first, he put these very watermelons to pieces] in front of this donkey”Footnote 41

Notice that these examples lack any obvious evaluative connotations. Instead, they seem to be dependent on a deictic concept of proximity. Mutual knowledge on the other hand involves contexts where the identity of the referent is known by both speakers, through their shared world knowledge, even though the referent has not been previously introduced in the linguistic context. As such, this usage is typical for interactional contexts, rather than narratives. The following two examples are not from the text corpus, but stem from free speech recorded by the author during a field trip in Sistan region in 2017.

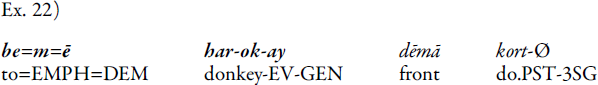

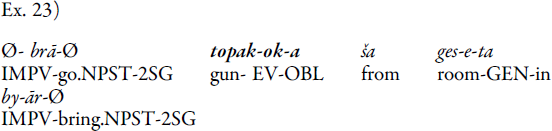

Example 23 is extracted from a dialogue between a man and his wife. The man comes from the outside and asks his wife to go and bring the gun, which is an item familiar to both speaker and addressee. The K-suffix on gun does not mean that the gun is a small gun.

“go and bring the gun from the room”Footnote 42

The following passage is extracted from free speech. A woman comes to her neighbor and says that she wants to take the bag, referring to a bag that both are familiar with. Again, the bag concerned is not of smaller size than would be expected of a bag generally, nor is it in the immediate proximate deictic space.

“I will take the bag”Footnote 43

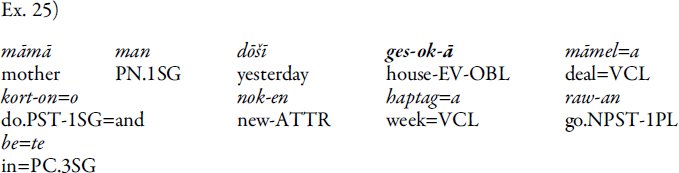

Similarly, in the following passage, the son comes to his mother and says that he bought the house, referring to a house that both are familiar with. Again, the house concerned is not smaller than would be expected of a house generally.

“mother, I have bought the house and we will move into it next week”Footnote 44

Summary

The corpus data for SisBal are on the whole quite similar to those of CoaBal, with evaluative connotations accounting for most usage. In SisBal, however, we also find nouns accompanied by proximal demonstratives, taking a K-suffix, with no obvious connotation of small size, or particular evaluative content. These examples provide some indication of how evaluative markers might evolve towards definiteness markers. One of the most striking findings for the cross-linguistic study of diminutives is that they are connected to some notion of endearment and familiarity.Footnote 45 In the case of the proximity and mutual knowledge contexts illustrated in examples 18–25, the concept of familiarity is reduced to physical proximity and shared common ground. It is thus not unreasonable to see an erstwhile evaluative marker becoming associated with proximity in a non-evaluative sense. The compatibility of K-suffixes with proximate demonstratives also turns out to be characteristic of K-suffixes in KorBal, where we find K-suffixes not only in proximate and shared knowledge contexts, but also in anaphoric and bridging contexts, i.e. those typically associated with definiteness cross-linguistically. The suggestion here is that the proximate and shared knowledge usage may have provided a bridging context for the transition from evaluative to definiteness marking.

K-suffixes as Definiteness Markers in Koroshi Narratives

As mentioned, in the Koroshi Balochi corpus (KorBal), the K-suffixes are both more frequent, but also (for some speakers at least), systematically associated with definiteness. In contrast to Sistani and Coastal Balochi, K-suffixes in Koroshi with evaluative or diminutive semantics have not been attested.

Before turning to the examples, it is necessary to briefly sketch the system of definiteness marking that broadly characterizes Balochi as a whole, and which is likewise found across most contemporary West Iranian languages. In all Balochi dialects, discourse-new, specific, singular NPs are overtly and consistently marked for indefiniteness. Definite NPs, on the other hand, are generally considered to lack any consistent signal of definiteness.

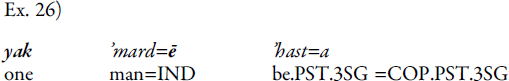

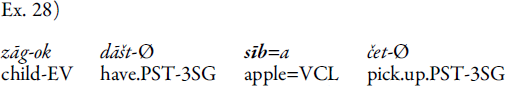

The marking of indefinites is illustrated from CoaBal, where the word yak “one” preceding the noun may be combined with a suffix =ī/=ē on the noun (yak mard=ē), or the noun may carry the suffix =ī/=ē without an additional yak. In example 28, we see a non-singular indefinite, sīb “apples,” which is simply left unmarked.

“there was a man”Footnote 46

“Once upon a time there was a king”Footnote 47

“the little child was picking up apples”Footnote 48

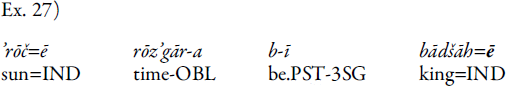

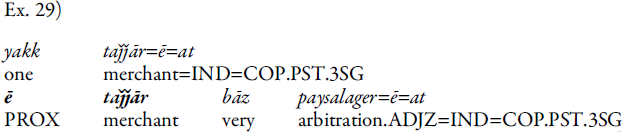

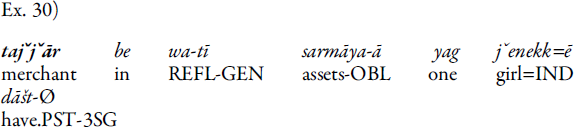

Once introduced, a referent has the status of definite (anaphoric definite). The two commonest strategies for indicating definiteness across Balochi (ignoring anaphoric pronouns and zero anaphora) are combining the noun with a proximate demonstrative, or using the bare form of the noun with no additional marking. The following examples from a SisBal narrative illustrate these two possibilities.Footnote 49 Following the introduction of the merchant, tajjār, as a singular indefinite, the second mention (anaphoric definite) takes the proximate demonstrative ē:

“there was a merchant, this merchant was a very wise person in arbitration”Footnote 50

After this introductory sequence, there are several lines of intervening text with zero anaphor referring to the merchant, before he is mentioned again as a bare noun:

“the merchant had one daughter as his (only) asset”Footnote 51

Similar examples with bare nouns in comparable contexts can be found in all dialects, and have been noted for Central Kurdish.Footnote 52 In sum, we can conclude that although discourse-new, singular nouns are consistently marked throughout Balochi, the marking of definiteness is not consistent. The two strategies most commonly mentioned are the use of the demonstrative, or the bare form of the noun.Footnote 53

However, Nourzaei et al and Nourzaei point out that in the Koroshi dialect there is a strong association of K-suffixes with definite NPs,Footnote 54 a fact that had hitherto not been observed. In the next section I illustrate the use of K-suffixes in KorBal. Examples for this section are extracted from published spoken texts.Footnote 55 There are, however, certain structural conditions that inhibit the use of the K-suffix in definiteness contexts, which are discussed below.

Anaphoric definiteness

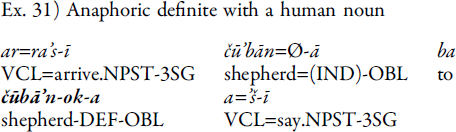

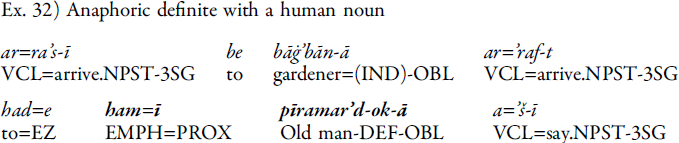

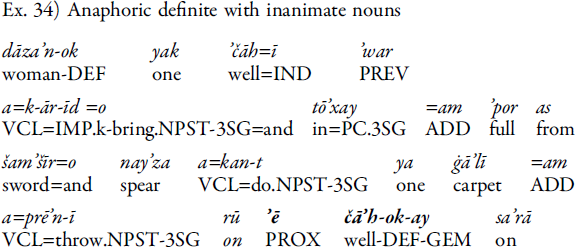

In KorBal, singular NPs that are anaphorically definite take a K-suffix, when the relevant structural conditions obtain. The following examples illustrate K-suffixes in anaphoric definite contexts, with both human and non-human nouns as in examples 31–4. Note that in example 31, the expected indefiniteness suffix may be elided before the oblique case marker.

“he arrived at [a place where there was a] shepherd, he said to the shepherd …”Footnote 56

The following examples illustrate anaphorically definite NPs which are accompanied by a proximate demonstrative, and marked with the K-suffix. This is a very frequent pattern for anaphoric definite contexts in KorBal:Footnote 57

“he came (lit. arrived) to a gardener. He went to this old man; he said…”Footnote 58

“the boy had a horse (lit. a horse was for the boy) which, every time this horse wanted to take…to give birth to her foal, she used to take it [and] throw it into the sea”Footnote 59

“the woman dug a well and filled it with swords and spears [and] she spread a carpet on this well”Footnote 60

Situational definiteness and the K-suffix

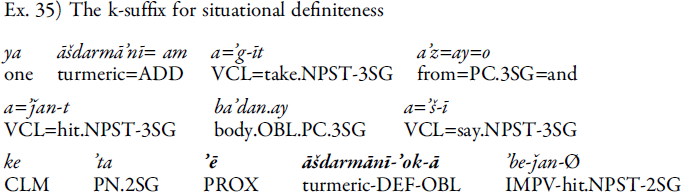

In situational definiteness contexts, Koroshi generally requires a demonstrative, usually combined with a K-suffix. Koroshi has a two-term system of demonstratives (ī/ē proximal and ā distal).Footnote 61 The combination of K-suffix with proximal ī/ē is more frequent then distal ā. There do not appear to be semantic constraints on the deictically modified nouns:

“so she got some turmeric from him and rubbed [it] on her body; he said /that/, ‘Rub this turmeric [on your body]’”Footnote 62

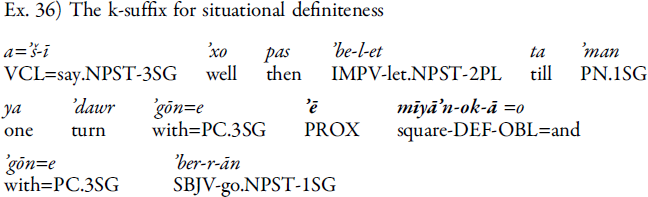

The following passage displays a situational definiteness context, where the demonstrative again combines with a K-suffix with mīyā'nokā “square.” The square has not been mentioned previously in the story. The king’s son points to the square and asks his father let him take a turn around this square.

“he said, ‘Alright, then let me take a ride around this square on it…’”Footnote 63

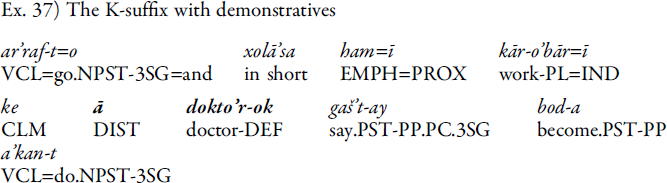

Example 37 shows a situational definiteness context, where a distal demonstrative combines with a K-suffix with dokto'rok “the doctor.” The doctor was previously introduced in the story in line 19. In the example below (line 24 of the narrative), the speaker refers back to the same referent.

“she went and, you know, did just what (lit. this very job that) that doctor told [her]”Footnote 64

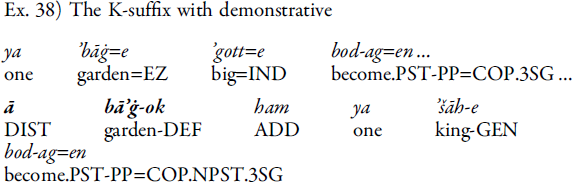

Similar to example 37, example 38 displays a situational definiteness context, where the demonstrative again combines with a K-suffix with bā'ġok “the garden.” The garden was introduced in the story previously in line 52. The narrator points to it in line 55 and says a king owned that garden.

“there was a big garden […] a king owned that garden”Footnote 65

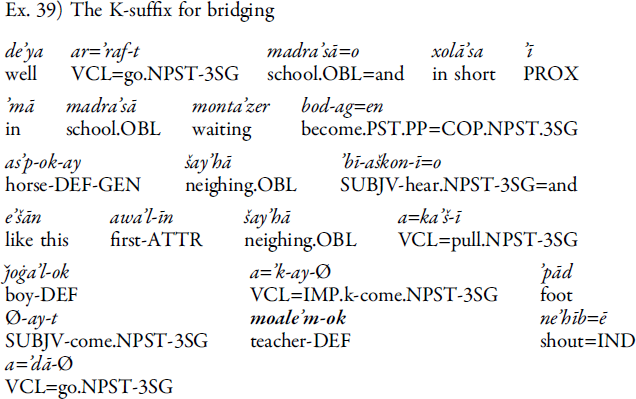

Bridging

Generally bridging contexts are signaled with a possessed noun (see “her foal” in example 33). There are some cases with K-suffix as moale'm-ok “the teacher” in example 39. The teacher has not been mentioned in the previous passage or even in the story. But it is familiar to the hearer from general knowledge, namely that a school has a teacher (note the lack of definiteness marking on the second mention of “school”).

“Well, he goes to school and, you know, at school he was waiting to hear the neighing of the horse, you know, when the foal neighs the first time, the boy is about to stand up, the teacher shouts at him”Footnote 66

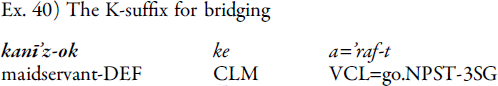

Similarly, in example 40 kanīz-ok “the maidservant” is marked with the K-suffix. Again, the referent has not been mentioned in the preceding clause and even in the story. But it is familiar to the hearer from general knowledge that a queen has a servant, or several.

“the maidservant went…”Footnote 67

Structural constraints on K-suffix

As mentioned, anaphorically definite nouns are generally marked with a K-suffix in Koroshi. However, the presence of the K-suffix is systematically inhibited under certain conditions, which are outlined below.Footnote 68

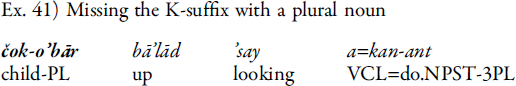

Plural

The nominal plural marker -obār/bār is unique to this dialect, and of uncertain origins. Nouns marked with this suffix never take a K-suffix, regardless of their definiteness status. For example, in example 41, “the children” is an anaphoric definite, but lacks a K-suffix due to the presence of the plural marker -obār.

“the children looked up”Footnote 69

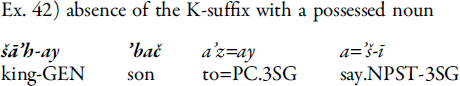

Possessed nouns

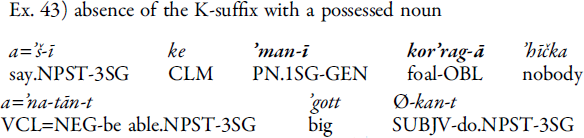

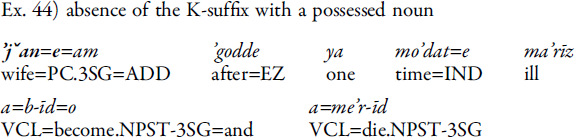

A noun can be possessed through an overt possessor NP or pronoun, or through a clitic possessive pronoun, or combination of an overt possessor NP plus a clitic possessive pronoun. The K-suffix is systematically absent from all possessed nouns, cf. “son,” foal, wife son and king in examples 42–45.

“The king’s son said to her”Footnote 70

“It said /that/, ‘No one can raise my foal’”Footnote 71

“after a while, his wife become sick and died”Footnote 72

“the king’s first son would die”Footnote 73

Certain prepositions

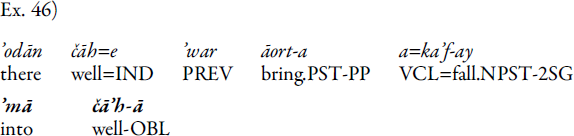

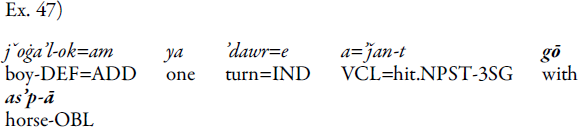

The data demonstrate that the K-suffix is absent in certain combinations with prepositions: mā “in(to)” and gō “with,” as in examples 46–47.

“dug a well there; you will fall into the well”Footnote 74

“the boy took a ride on horse”Footnote 75

Certain nouns

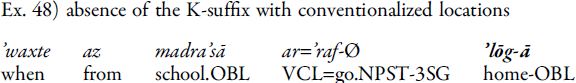

The data indicate that the K-suffix is always absent with certain nouns, especially those expressing conventionalized locations, such as lō'gā “home” and madrasā “school” in examples 48–49.

“when he went home from school”Footnote 76

“Well, he goes to school and, you know, at school he was waiting […]”Footnote 77

Titles and proper nouns

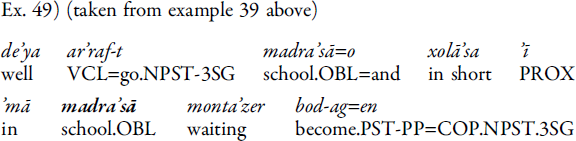

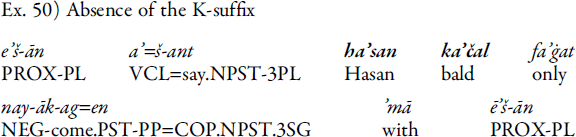

Generally, the K-suffix is absent from titles and proper nouns, an in examples 50–51. Note, king and mullah are considered proper nouns in Koroshi and also other Balochi dialects. The same holds for Central Kurdish narrative texts.Footnote 78

“they said, ‘Only Hasan the Bald has not come along with these’”Footnote 79

“so the king went and took another woman”Footnote 80

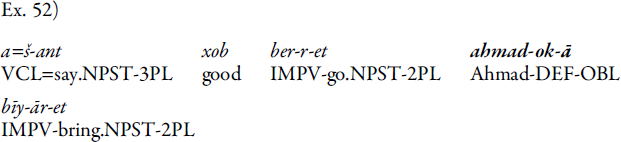

However, two examples are attested of the K-suffix with proper noun, as in the following example.

“They said, ‘Alright, go and bring Ahmad’”Footnote 81

Unexpected absence of the K-suffix

According to the analysis presented so far for Koroshi, a singular noun in a definiteness context should be marked with a K-suffix, unless the above-mentioned structural constraints obtain. However, there nevertheless remains a residue of nouns in definiteness contexts that lack the K-suffix, hence the term “unexpected absence” of K-suffix used. The number of such unmarked definite NPs varies considerably across different speakers in our corpus (see below), indicating considerable inter-speaker variation.Footnote 82

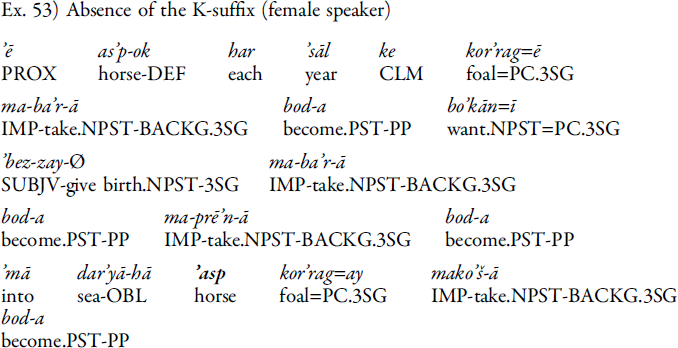

When NPs are anaphorically definite, but lack a K-suffix, the noun is in its bare form. In example 53 'asp “horse” in the first line is marked with the K-suffix, but in the last line the same noun occurs with the same reference, but without a K-suffix.

“every time this horse wanted to take…to give birth to her foal, she used to take it [and] throw it into the sea; the horse used to kill her foal”Footnote 83

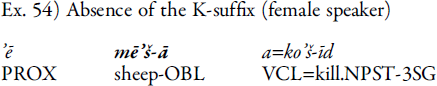

In example 54 mē'šā “the sheep” is a previously introduced referent but it appears as a bare noun without the K-suffix.

“he slaughtered the sheep”Footnote 84

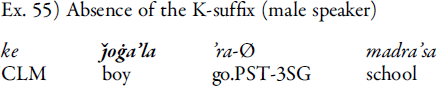

Similarly, ǰoġa'la “the boy” in example 55 is a previously introduced referent who is the main participant in the story but it appears as a bare noun without the K-suffix.

“when the boy went to school”Footnote 85

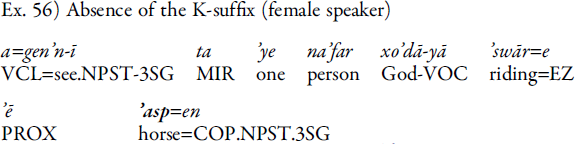

Example 56 below is somewhat different. The lack of the expected K-suffix on 'asp “horse” may be related to a shift in perspective in the narration: here the narration is presented from the perspective of the king’s daughter, who expresses surprise at the events unfolding before her:

“oh God, one person had mounted this horse”Footnote 86

Finally, there are examples of contextually definite nouns with general plural semantics, which lack the expected K-suffix, although the nouns concerned are not overtly plural marked. In example 57, noġ'lā “the candy”Footnote 87 is anaphoric definite, but notionally it consists of an indeterminate number of small items.

“he saw that they were about to catch [him], so he threw (lit. into the air) the candy from above”Footnote 88

Similarly, in example 58 oš'torā “camel” refers to more than one camel, even though it lacks the plural marker -obār.

“she is giving the camels a hard time (lit. camel)”Footnote 89

These examples are suggestive of an individualizing function of the K-suffix: it is only compatible with nouns that are both grammatically singular (lack plural marking), and notionally individualized.

Summary Koroshi

K-suffixes in Koroshi are associated with definiteness contexts, most typically anaphoric and deictic. They are systematically excluded from indefiniteness contexts, and are not associated with obvious evaluative or diminutive semantics. It is in this sense that we speak of a definiteness function of the K-suffix in Koroshi, and in this sense, Koroshi is clearly distinct from Coastal and Sistani Balochi. However, in Koroshi definiteness is a necessary but not sufficient criterion for the K-suffix: there are still many notionally definite NPs in our corpus which do not take a K-suffix. First of all, we noted certain structural conditions that inhibit the presence of a K-suffix:

-

1. Plural marking of the noun.Footnote 90

-

2. In combination with possessors, either clitic pronouns or otherwise.

-

3. In combination with certain prepositions.

-

4. In combination with certain nouns indicating conventional locations.

-

5. When the noun can be construed as a title or proper noun.

The extent of the residue of definite but unmarked NPs varies from speaker to speaker, and according to genre and speech situation. In the next section, we explore the quantitative data from our corpus in order to shed light on the nature of the changes that have occurred in Koroshi Balochi.

The Emergence of Definiteness: Evidence from the Corpus and the Questionnaire

Work on the grammaticalization of definiteness marking has been dominated by studies on the languages of western Europe, most of which have definite articles which are clearly innovations when compared to the oldest attested forms of these languages. Across these languages, the source of the definite article is some form of deictic element (a “D-element” according to Himmelmann),Footnote 91 and this has become the main paradigm for understanding the diachronic development of definiteness marking cross-linguistically.

However, the Koroshi definiteness suffix has an entirely different source construction, namely from an evaluative suffix, and it remains an open question whether a similar pathway is to be expected. For one thing, as we have noted in examples 32–33 above, the K-suffix frequently co-occurs with demonstratives, which is ruled out for the development of demonstratives to articles.

While we lack historical records of earlier stages of Balochi, we do have extensive collections of spoken narrative texts from contemporary speakers, across all three dialects. Comparing the findings from these texts allows us to formulate some initial hypotheses regarding the developmental sequence that led to the current state. The corpus consists of spoken Balochi narratives from the three dialects, mostly from narrative genres, which were originally published in Nourzaei and colleagues’ studies.Footnote 92 Total narrative texts are thirty-three, thirty-nine and eight texts for Koroshi, Coastal and Sistani Balochi respectively. An overview of the corpus is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary overview of corpus

A second source of data is a questionnaire conducted in 2018 and 2019 with thirty-six Balochi speakers, which is treated below. But first we consider two metrics from the narrative corpus: overall frequencies of K-suffixes, and frequency of K-suffixes with highly topical referents.

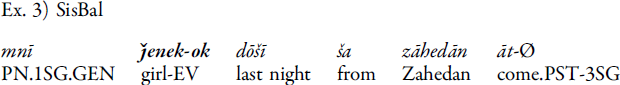

Overall frequency of K-suffixes

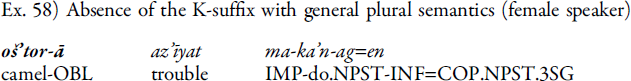

The first measure we consider is the overall number of K-suffixes across all texts in the corpus per orthographic word, normalized to a value of frequency per 1,000 words to enable comparison across texts of different length. Quite a large number of texts have fewer than 500 words overall, and in many of them the number of K-suffixes is zero. Given that a value for zero in a small text is not particularly significant, while zero occurrences in a larger text is much more significant, we excluded texts of fewer than 500 words for the purposes of this calculation. The results for these three dialects are shown in the box-plot in Figure 2; horizontal bars represent median values, the cross is the mean. The boxes cover the second and third quartiles of the data. Each data point represents a text.

Figure 2. Overall frequency of the K-suffixes per 1,000 words.

There are a number of points of interest here. First, the hypothesis that overall frequency would increase with a shift towards definiteness function is confirmed.Footnote 93 In KorBal, the mean value of K-suffixes per 1,000 words is 6.4, almost double that of CoaBal (3.9). However, it is also clear that the higher frequency of K-suffixes in KorBal is largely the result of two data outliers, with 41.3 and 30.3 K-suffixes per 1,000 words respectively, more than double the figure for any other texts. Thus, KorBal is not characterized by a consistently high level of K-suffixes that one would expect if the forms were uniformly grammaticalized as definiteness markers in this dialect.

However, overall frequency is at best a very crude measure of grammaticalization. Recall that the qualitative investigation of the three dialects showed that in Coastal and Sistani Balochi, K-suffixes are used with evaluative and diminutive senses. Given that K-suffixes in these dialects are not associated with a predictable and commonly recurring function, we would not expect a uniform frequency of use, and indeed, frequency of evaluative usage may simply be a matter of style and nature of interaction. In Koroshi, on the other hand, K-suffixes are not associated with evaluative and diminutive semantics, but are associated with definiteness.Footnote 94 However, the association is not fully regular; as mentioned, there are structural conditions that inhibit the K-suffix, and there are also instances of definite NPs that lack the expected K-suffix, for reasons that are not fully understood. Thus, we can expect in Koroshi on the one hand a drop in frequency of the K-suffixes, because they are no longer used in diminutive and evaluative functions. On the other hand, we can expect an increase, because they are associated with definiteness. How these two changes are weighted relative to one another is difficult to assess at present, especially given the somewhat unpredictable and context-sensitive use of evaluative.

The second confounding issue is massive inter-speaker differences. The two outliers in the Koroshi corpus both stem from the same speaker, a thirty-year-old female, and both are renderings of a traditional folk tale. Our corpus also includes another rendering of the same folk tale (“The King's Son”), by a male speaker, fifty-eight years old. The rate of K-suffixes in the male speaker's text is just 2.1, as opposed to 41.3 by the female speaker. This suggests that genre is not the decisive factor, as there are other folk tales in the corpus with very low levels of K-suffixes. Considering now the data from CoaBal, we likewise find three outliers. The two highest values (34.8 and 27.8) stem from the same female speaker, aged fifty, while the third (11.5) is from a twenty-five-year-old woman. The texts concerned are procedural and oral history, rather than traditional folk tales.

The overall picture thus suggests an idiosyncratic usage of K-suffixes, with a small number of female speakers using an overall higher frequency of K-suffixes, and presumably acting as innovators in a development towards definiteness usage. In Coastal Balochi, high rates of K-suffixes are found in procedural and oral history texts, as opposed to traditional narratives, and the high rates of K-suffixes in these texts are associated with evaluative and diminutive functions. Thus, the outliers in Coastal Balochi have a different underlying cause to those of Koroshi, where the high rates of K-suffixes are associated with definiteness marking. What we can provisionally state is that (a) high rates of K-suffixes, regardless of function, are characteristic for female speakers; (b) for Coastal Balochi, the evaluative and diminutive senses are found most frequently in non-conventionalized narratives, as opposed to conventional narratives (folk tales).

K-suffixes in anaphoric definite contexts: marking VIPs

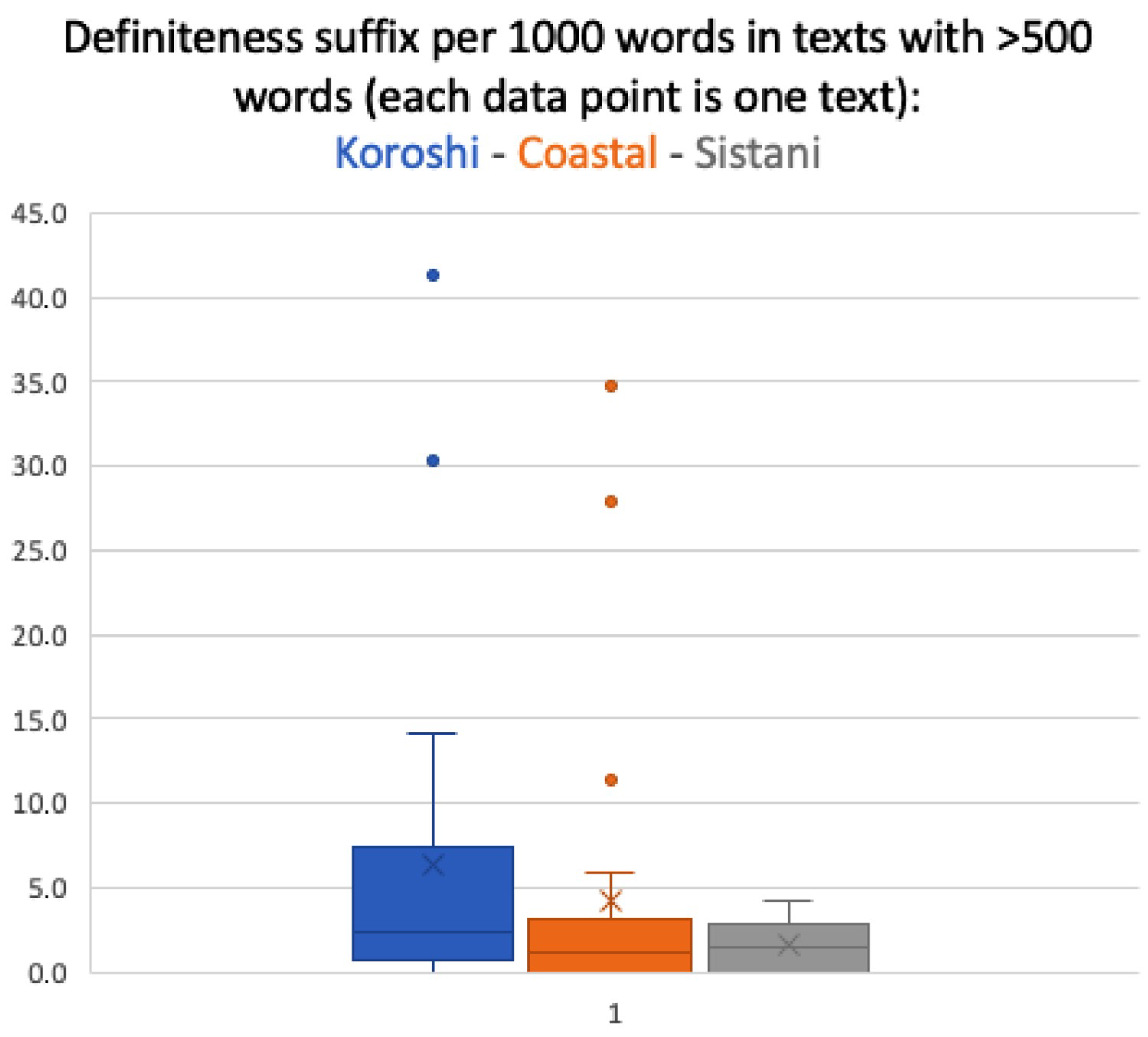

An alternative perspective on the data is to consider uncontroversially definite contexts, and to investigate how frequently different dialects realize K-suffixes in these contexts. For this purpose, I selected the most highly persistent referents (so-called Very Important Participants, VIPs)Footnote 95 in those folk tales for which several renderings were available. I selected one rendering by a male and one by a female speaker from each dialect, and coded all mentions of two to four VIPs in each folk tale. While this is only a small subset of possible definiteness contexts, it has the advantage of reducing the variables by focusing on anaphoric definite contexts with text-topical referents.

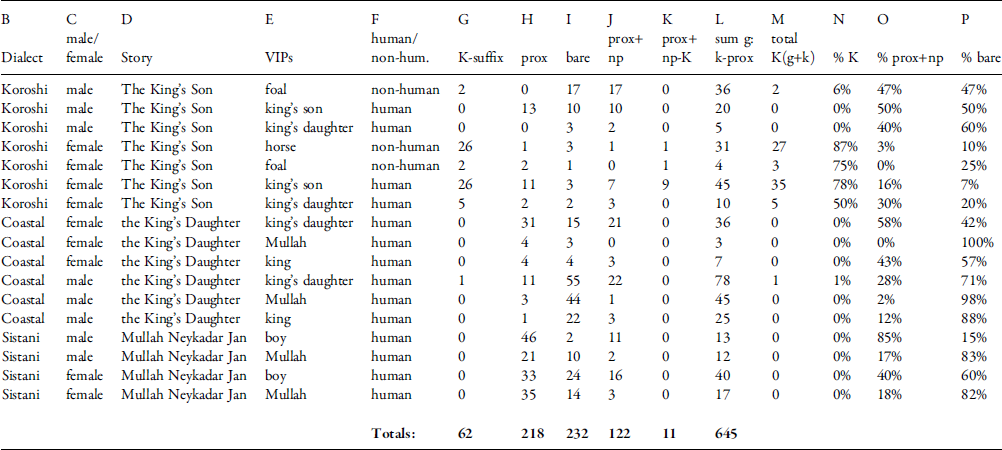

There are three folktales, entitled “The King’s Son,” “The King’s Daughter” and “Mullah Neykadar Jan” for Koroshi, Coastal and Sistani Balochi respectively. They are based on oral recordings, originally published in Nourzaei and colleagues’ studies.Footnote 96 The VIPs for “The King’s Son” folktale are foal, king’s son, king’s daughter and horse. The VIP for “The King’s Daughter” folktale are king’s daughter, mullah and king. The VIP for the “Mullah Neykadar Jan” folktale are boy and mullah. The raw figures for each text are provided in the Appendix 1.

Figure 3 visualizes the main results (we distinguish male and female speakers in Koroshi, while the differences between males and females in Coastal and Sistani are negligible and have been collapsed here). The figures provide the percentages of three form types: nouns with a K-suffix, bare nouns, and proximal demonstrative-plus-noun marked NPs.

Figure 3. Percentages of different forms used for VIPs in narratives.

It is evident that with these highly persistent referents, the use of K-suffixes is negligible outside of Koroshi. Within Koroshi, it is the female speaker that makes the most extensive use of K-suffixes (almost 80 percent of all mentions of a VIP included a K-suffix). For all other speakers, the normal means of referring to a VIP is either with a bare noun or with a prox-plus-noun. This is essentially the inherited system of definiteness marking, as was outlined above. We can see that this system still accounts for about 25 percent of the Koroshi female speaker's VIPs, i.e. this is the residue of definite NPs that lack a K-suffix which was discussed above, plus some instances where structural factors inhibit the K-suffix. The focus on this kind of anaphoric definite referents makes it possible to observe that largely systematic use of K-suffixes for definiteness in the speech of Koroshi female speaker. According to the criteria outlined in Becker this would probably qualify as an anaphoric definite article,Footnote 97 though this is to some extent a matter of how one wishes to define “definite article.”Footnote 98

Summary of narrative corpus data

The corpus data, combined with the qualitative analysis of the previous sections, reveal that in Sistani and Coastal Balochi, K-suffixes are largely restricted to evaluative contexts. Their overall frequency varies very considerably according to speaker, content and genre, which is what can be expected of evaluative as opposed to descriptive or inflectional morphology. The use of evaluative morphology is situationally sensitive, and can therefore be expected to adapt flexibly towards content, formality, speaker style, etc. In Sistani Balochi, however, we already find examples of K-suffixes combining with nouns in recognitional and deictic contexts, without any obvious evaluative or diminutive connotations. This type of usage is also shared by Koroshi. I consider this to be first stage in co-opting evaluative morphology into a marker of definiteness.

Koroshi differs from the other two varieties in its almost complete lack of evaluative functions, and also in having certain structural constraints on the use of the K-suffixes (incompatible with plural marking, for example). As in Sistani, K-suffixes in Koroshi are used together with demonstratives in recognitional and deictic contexts, as illustrated above. But in Koroshi, we find a female speaker who uses the K-suffix systematically without a demonstrative in anaphoric definite contexts. She appears to be a leader in this development. More recent questionnaire data (see below) suggests that this usage is, at least in non-traditional genres, now typical for Koroshi.

Questionnaire data

The questionnaire data stem from a questionnaire using a set of 102 items, built into six “mini-narratives,” each recounting short episodes of approximately ten sentences. Speakers were presented the narratives in Persian and asked to translate them orally into their dialect of Balochi. Their narratives were recorded with a mobile telephone, and the relevant NPs coded for presence vs. absence of K-suffix, and a number of other features.Footnote 99 This is part of a larger ongoing survey across West Iranian languages; the results here are from the initial pilot from Balochi, based on twelve speakers per dialect. I present here only a subset of the data, primarily to highlight the differences between these results and those based on the narrative texts.

Table 2 shows the percentage of nouns carrying a K-suffix in the respective contexts: anaphoric, bridging, possessed, first mention (indefinite) and non-referential/generic (as in negated existentials, such as “in those days there were no cars”). When we consider the Koroshi data, we find about half of the nouns in anaphoric and bridging contexts take K-suffixes. Other nouns in these contexts are accompanied by proximal demonstratives, or were in plural, and were thus not counted here. In general, and across all speakers of this dialect, we find a fairly systematic marking of anaphoric definiteness. Furthermore, we find consistent observance of the structural constraint against possessed nouns, and a complete absence of K-suffixes in the indefinite contexts. On the whole, this is the system found with the outlier female speaker discussed previously. Interestingly, it seems to be applied consistently by all speakers who responded to the questionnaire, suggesting that this system is now the norm, at least for non-traditional speech events.

Table 2. Percentage of the K-suffixes, based on questionnaire (twelve speakers per dialect, rounded mean percentages of all speakers’ responses)

Note that the raw figures will be made available for publication.

The biggest surprise is the staggering overall frequency of K-suffixes in Sistani Balochi, in all contexts. But note that this increase is not related to definiteness: first mentions (indefinites) and even generic nouns show high frequencies of K-suffixes, thus ruling out any systematic link to definiteness. Nor is there any structural constraint against the combination of K-suffix with a possessed noun. The use appears to be remarkably indiscriminate, with a scattering of K-suffixes across NPs in very different information-structural contexts, presumably linked to situational factors, or the lexical semantics of the nouns in question. In Sistani, then, we have an increase in frequency (at least for this text type), but it does not translate onto a development towards definiteness. Finally, in Coastal we find the overall levels of frequency are much less than for Sistani, with a possible, though weak, trend towards preference for definite contexts. While much remains to be explained from these data, they do confirm that the Koroshi dialect has diverged generally from the other two, in that the K-suffix is now firmly restricted to definiteness contexts, and is subject to structural constraints typical of inflectional, as opposed to evaluative, morphology.

Summary

Across Balochi we find the reflexes of presumably cognate and originally evaluative morphology, which has developed in different ways in different dialects. While two dialects maintain evaluative uses, which are not constrained by definiteness, and not subject to structural constraints, in Koroshi dialect, the evaluative usage is unattested, and the suffix is not compatible with indefinite contexts. In both Sistani and Koroshi Balochi, there are combinations of demonstrative marked nouns with a K-suffix, in deictic and recognitional contexts, although in Sistani overall evaluative usage prevails. In the narrative texts investigated, we find one female speaker of Koroshi who has taken this usage a step further and now uses the K-suffix as a distinct marker of anaphoric definiteness. This usage was confirmed by the investigation of the VIP contexts above. Questionnaire data suggest that in Koroshi this kind of usage is now the norm, at least for the (informal) situation evoked by the questionnaire response.

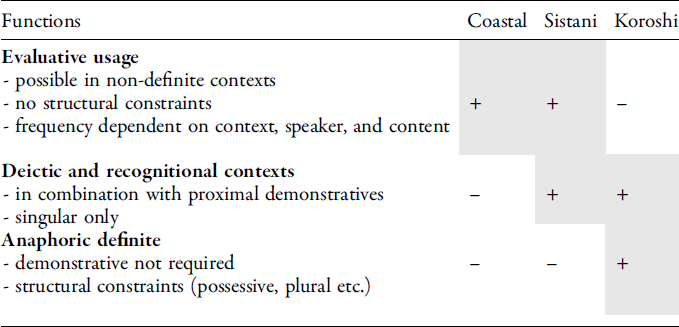

Overall, the distribution of different functions across the dialects are suggestive of a developmental pathway that is summed up in Table 3. Evaluative usage is compatible with deictic and recognitional usage, as the latter are anchored to a concrete and interactive speech context, involving some form of “attention direction” on the part of the speaker. Evaluative usages may then disappear entirely, while the deictic and recognitional usages extend to include non-deictic anaphoric tracking, which would be more independent of setting, and not necessarily dependent on immediate interaction. We further surmise that this development would initially be restricted to non-traditional contexts (procedural and other types) but possibly via the leadership of female speakers, can also be extended into traditional narrative domains.

Table 3. Summary overview of grammaticalization path of evaluative to definiteness

These findings, though currently still provisional, suggest that the development of definiteness marking can proceed down a pathway that is distinct from the one normally assumed for demonstrative-based definite marking, though the endpoint may be quite similar. The starting point here is an evaluative marker, typically used in interactional contexts, coupled with some diminutive connotations. This becomes associated with deictic marking, a kind of attention-seeking device, which presumably provides the bridging context for a further development towards a marker of anaphoric definiteness. In the final stages, the K-suffix is consistently associated with anaphoric definiteness contexts, though this system continues to coexist with the inherited system of bare-noun marking of definiteness (example 30 above). The basic system of definiteness marking with a K-suffix is thus similar to more familiar article-based systems, for which anaphoric definiteness is generally the core function.

Still, a number of differences can also be discerned, in particular the constraint against definiteness marking in combination with plural marking. Becker finds no typological evidence for the incompatibility of definiteness markers with plural number (though there is clear evidence for the incompatibility of indefinite markers and plural number).Footnote 100 The Balochi constraint thus remains something of a puzzle, particularly when compared to definiteness marking in Central Kurdish, likewise based on a K-suffix, for which no such constraint exists.Footnote 101 This is a topic for future research.

Finally, with regard to why only Koroshi should have gone down the pathway from evaluative to definiteness, there is no definitive answer, but I can point to possible areal considerations. Koroshi is the most westerly variety of Balochi, closest to the Mesopotamian/Zagros region where a number of other Iranian languages have definiteness marking (Central and Southern Kurdish, Hawrami, Bakhtiari, Shirazi Persian),Footnote 102 probably in response to the influence of Semitic languages such as Northeastern Neo-Aramaic and Arabic.Footnote 103 Even Turkic languages of west Iran have borrowed definiteness marking from neighboring varieties of Kurdish,Footnote 104 suggesting that areal influence is operative in the realm of definiteness marking, as other scholars have also suggested.Footnote 105 But dialect-internal features may also have played a role, for example the reduction of case marking in Koroshi as opposed to Sistani and Coastal, which may have favored the emergence of an additional nominal category such as definiteness. Again, this needs to be tested in a more comprehensive survey of Western Iranian languages, which is currently underway. The ongoing work suggests that several Western Iranian languages have developed some nascent form of definiteness marking, based on evaluative morphology. The Balochi case presented here is by far the most richly documented, and will provide a benchmark for further studies from Iranian, as well as broadening the database for our understanding the development of definiteness cross-linguistically.

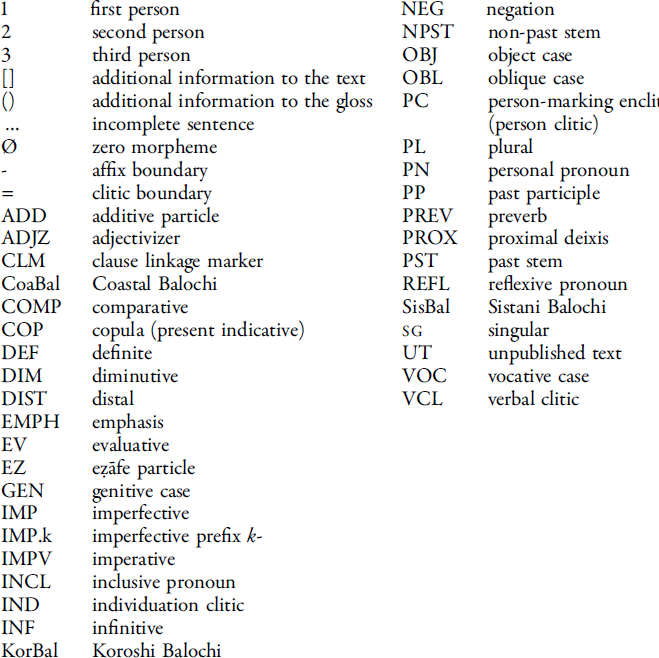

Abbreviations

Appendix 1: Raw data for VIP-referents, Figure 3 of main manuscript

Note: ʻProx' (Column H) refers to the use of a stand-alone proximal demonstrative as an anaphoric pronoun, which have been excluded from the counts.