Article contents

The Right Path: A Post-Mongol Persian Ismaili Treatise

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2022

Abstract

The Epistle of the Right Path (Risāla-yi Ṣirāṭ al-Mustaqīm) is an anonymous treatise, possibly dating to the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century. It may be the earliest Persian Ismaili prose work of the post-Mongol period to come to light, and is here introduced, discussed, edited and translated. A clearly articulated, philosophically inclined treatment of numerous themes in Ismaili thought, the text draws frequently from Nasir al-Din Tusi's spiritual autobiography, The Voyage (Sayr wa-Sulūk). Its subject matter includes the correspondence between the exoteric and esoteric worlds, the concept of the divine command through which creation attains perfection, the role of the Imam and the esoteric hierarchy, and the fact that esoteric exegesis (ta 'wīl) of divine revelation must be compatible with the principles of the intellect.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The International Society for Iranian Studies 2010

Footnotes

I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Faquir M. Hunzai and Dr. Ahmad Mahdavi-Damghani, both of whom provided invaluable help in the preparation of this article.

This article is dedicated to the memory of the late Alijah Datoo Meru.

References

1 Cited in Daftary, Farhad, The Ismā‘īlīs: Their History and Doctrines, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, 2007), 15.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2 ‘Alā’ al-Dīn ‘Aṭā-Malik Juwaynī, Ta’rīkh-i Jahāngushāy, ed. by Qazwīnī, Muḥammad, 3 vols. (Leiden, 1912–37), vol. 3, 269–270Google Scholar, trans. by Andrew Boyle, John, The History of the World-Conqueror, 2 vols. (Cambridge, MA, 1958), vol. 2, 719.Google Scholar

3 Juwaynī, , Jahāngushāy, vol. 3, 186–187Google Scholar, 269–270, vol. 2, 666, 719.

4 Daftary, Farhad, Ismaili Literature (London, 2004), 59Google Scholar, Daftary, The Ismā‘īlīs: Their History and Doctrines, 403ff.

5 Daftary, Farhad, The Ismā‘īlīs: Their History and Doctrines (Cambridge, 1990), 435.Google Scholar He is preceded in this regard by Hamid Algar, “The Revolt of Āghā Khān Maḥallātī and the Transference of the Ismā‘īlī Imamate to India,” SI, 29 (1969): 55; Mujtaba Ali, Syed, The Origin of the Khojāhs and their Religious Life Today (Würzburg, 1936), 55Google Scholar; Howard, E. I., The Shia School of Islam and its Branches, Especially that of the Imamee-Ismailies: A Speech Delivered by E. I. Howard, Esquire, Barrister-at-Law, in the Bombay High Court, in June, 1866 (Bombay, 1866), 57–59.Google Scholar

6 In this regard, see, for example, Eboo Jamal, Nadia, Surviving the Mongols: Nizārī Quhistānī and the Continuity of Ismaili Tradition in Persia (London, 2002)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Virani, Shafique N., The Ismailis in the Middle Ages: A History of Survival, A Search for Salvation (New York, 2007).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

7 This treatise was first presented as “Risāla-yi Ṣirāṭ al-Mustaqīm,” in Seekers of Union: The Ismailis from the Mongol Debacle to the Eve of the Safavid Revolution, ed. by Virani, Shafique N. (PhD dissertation, Harvard University, 2001).Google Scholar Further references and discussion may be found in Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages, 26, 50, 56, 60–61, 94, 99.

8 The quotation attributed to “pīr-i Rūmī” is not found in the known oeuvre of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (d. 672/1273). It is not impossible that Shams-i Tabrīzī himself may have composed some odd bits of poetry, including the fragment found here.

9 In this regard, see Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages, 107, 121.

10 Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages, 120, 168–169, 176–178.

11 Muḥammad Riḍā b. Khwāja Sulṭān Ḥusayn Ghūriyānī Khayrkhwāh-i Harātī,Taṣnīfāt-i Khayrkhwāh-i Harātī, ed. Ivanow, Wladimir (Tehran, 1961), 78.Google Scholar

12 For more information on this transfer, see Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages, 124–126 and Shafique N. Virani, “The Voice of Truth: Life and Works of Sayyid Nūr Muḥammad Shāh, a 15th/16th Century Ismā‘īlī Mystic” (MA thesis, McGill University, 1995), 17–22.

13 Some of the parallel passages are indicated in the notes.

14 Representative translations of selected poems may be found in Hunzai, Faquir M. and Kassam, Kutub, ed. and trans., Shimmering Light: An Anthology of Ismaili Poetry (London, 1996), 84.Google Scholar

15 Quran 6:73 and 7:54. This topic is dealt with extensively from an Ismaili perspective by al-Shahrastānī (d. 548/1153) in his majlis delivered at Khwarazm; see Muḥammad b. ‘Abd al-Karīm al-Shahrastānī, Majlis-i Maktūb-i Shahrastānī mun‘aqid dar Khwārazm, trans. by Steigerwald, Diane, Majlis: Discours sur l'Ordre et la Création (Saint-Nicholas, 1998).Google Scholar Al-Shahrastānī was the author of the well known Kitāb al-Milal wa-al-Niḥal on religions and Islamic sects.

16 Abū Ya‘qūb al-Sijistānī, Kashf al-Maḥjūb, trans. by Corbin, Henry, Kashf al-Maḥjūb: Le Dévoilement des Choses Cachées (Lagrasse, 1988), 33–45Google Scholar and partial English trans. by Landolt, Hermann as “Unveiling of the Hidden,” An Anthology of Philosophy in Persian, ed. by Nasr, S. H. and Aminrazavi, M. (Oxford, 2001), vol. 2, 80–124.Google Scholar

17 Al-Sijistānī, Kashf/Dévoilement, 13.

18 Abū Ya‘qūb Isḥāq b. Aḥmad al-Sijistānī, Kitāb al-Iftikhār, ed. Poonawala, Ismail K. (Beirut: 2000), 91Google Scholar, Abū Ya‘qūb al-Sijistānī, Kitāb al-Iftikhār, ed. Ghālib, Muṣtafā (Beirut, 1980), 29Google Scholar, trans. in Faquir M. Hunzai, “The Concept of Tawḥīd in the Thought of Ḥamīd al-Dīn al-Kirmānī” (PhD dissertation, McGill University, 1986), 65. Cf. Walker, Paul E., Ḥamīd al-Dīn al-Kirmānī: Ismaili Thought in the Age of al-Ḥākim (London, 1999), 83–89Google Scholar and de Smet, Daniel, La Quiétude de l'Intellect: Néoplatonisme et Gnose Ismaélienne dans l'Oeuvre deḤamīd ad-Dīn al-Kirmānī (Xe/XIe s.) (Leuven, 1995), 35–100.Google Scholar

19 Cited in Walker, Paul E., “An Ismā‘īlī Answer to the Problem of Worshiping the Unknowable, Neoplatonic God,” American Journal of Arabic Studies, 2 (1974): 13Google Scholar, cf. Early Philosophical Shiism: The Ismaili Neoplatonism of Abū Ya‘qūb al-Sijistānī (Cambridge, 1993), 75.Google Scholar

20 al-Sijistānī, Kashf/Dévoilement, 44–45.

21 Kashf al-Maḥjūb, translated in Kamada, Shigeru, “The First Being: Intellect (‘aql/khiradh) as the Link Between God's Command and Creation According to Abū Ya‘qūb al-Sijistānī,” The Memoirs of the Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo 106 (1988): 5.Google Scholar

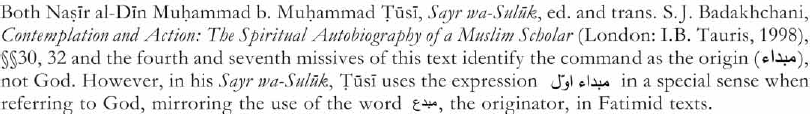

22 This and the discussion that follows draw upon the present treatise, Naṣīr al-Dīn Muḥammad b. Muḥammad Ṭūsī, Sayr wa-Sulūk, ed. and trans. by Badakhchani, S. J., Contemplation and Action: The Spiritual Autobiography of a Muslim Scholar (London, 1998)Google Scholar, which explains a number of presumptions made in the present treatise, and the excellent summary and analysis of Ṭūsī's philosophical arguments in Landolt, Hermann, “Khwāja Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (597/1201–672/1274), Ismā‘īlism, and Ishrāqī Philosophy,” in Naṣīr al-Dīn Ṭūṣī: Philosophe et Savant du XIIIe Siècle, ed. by Pourjavady, N. and Ž. Vesel (Tehran, 2000), 17–22.Google Scholar

23 With regard to some of the names found in the treatise, reference should be made to Ivanow, Wladimir, “Noms bibliques dans la mythologie ismaélienne,” Journal Asiatique, 237 (1949): 249–255.Google Scholar

24 Ṭūsī, Sayr wa-Sulūk, 1–22.

25 The parallel passage is found in Ṭūsī, Sayr wa-Sulūk, §31.

26 It is difficult to establish whether this entire passage is, indeed, a quotation from the Risālat al-Ḥuzn or whether the author of the Risāla-yi Ṣirāṭ al-Mustaqīm is merely alluding to the Imam ‘Abd al-Salām's having mentioned this matter in the treatise. In view of the anonymous author's extensive quotations of the Sayr wa-Sulūk, the former seems more likely.

27 Large portions of this missive are drawn from Ṭūsī, Sayr wa-Sulūk, §32.

28 An allusion to Quran 52:4.

29 An allusion to the fabulous goblet of the Iranian king Jamshīd, in which the entire world could be seen.

30 An allusion to Quran 23:20.

31 Cf. Ṭūsī, Sayr wa-Sulūk, the last few lines of §32.

32 I.e., the ḥujjat-i a‘ẓam, the highest rank of the da‘wa after the Imam, sometimes referred to as the bāb.

33 The full text of this poem can still be found in scattered manuscripts of the writings of Ra’īs Ḥasan. The first verse is:

![]()

34 As indicated in the notes to the Persian edition, this is also a poem of Ra’īs Ḥasan that is frequently quoted in Ismaili works. The full text of the poem is still extant in manuscript form. The first couplet is:

![]()

35 Cf. Genesis 1:26, “And God said: Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.”

36 For this translation of the verse, see Ṭūsī, Sayr wa-Sulūk, 69-70 n33. For the following sentences, cf. Sayr wa-Sulūk, §32.

37 Parts of this missive parallel Ṭūsī, Sayr wa-Sulūk, §§20–21.

38 The parallel passages are found in Ṭūsī, Sayr wa-Sulūk, §36, followed by §§33–35.

39 On the concept of “thingness,” see Arnaldez, R., “S hay,” Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. (online version) (Leiden, 2008)Google Scholar, Brill Online, University of Toronto subscription, http://www.brillonline.nl.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/subscriber/entry?entry=islam_SIM-6881 (accessed 6 October 2008). What the author may have in mind here is the Quranic dictum, “Indeed his command, when he intends a thing is only that he says to it: “Be!” And it is” (36:82).

40 The parallel passages are found in Ṭūsī, Sayr wa-Sulūk, §§36–37.

41 The translation of the preceding paragraph is tentative, as the text appears to be partially corrupt. The discovery of another manuscript may help solve the ambiguities.

42 The meaning of this verse is obscure, and it does not seem to appear in Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī's known oeuvre. A tentative translation is given. The word yarqū has been understood in the sense of yarghū.

43 ![]()

44 ![]()

45 ![]()

46 ![]()

47 ![]()

48 ![]()

49 ![]()

50 ![]()

51 ![]()

52 ![]()

53 ![]()

54 ![]()

55 ![]()

56 ![]()

57 ![]()

58 ![]()

59 ![]()

60 ![]()

61 ![]()

62 ![]()

63 ![]()

64 ![]()

65 ![]()

66 ![]()

67 ![]()

68 ![]()

69 ![]()

70 ![]()

71 ![]()

72 ![]()

73 ![]()

74 ![]()

75 ![]()

76 ![]()

77 ![]()

78 ![]()

79 ![]()

80 ![]()

81 ![]()

82 ![]()

83 ![]()

84 ![]()

85 ![]()

86 ![]()

87 ![]()

88 ![]()

89 ![]()

90 ![]()

91 ![]()

92 ![]()

93 ![]()

94 ![]()

95 ![]()

96 ![]()

97 ![]()

98 ![]()

99 ![]()

100 ![]()

101 ![]()

102 ![]()

103 ![]()

104 ![]()

105 ![]()

106 ![]()

107 ![]()

108 ![]()

109 ![]()

110 ![]()

111 ![]()

112 ![]()

113 ![]()

114 ![]()

115 ![]()

116 ![]()

117 ![]()

118 ![]()

119 ![]()

120 ![]()

121 ![]()

122 ![]()

123 ![]()

124 ![]()

- 2

- Cited by