Management Implications

Phenological and resource allocation patterns are useful in developing species-specific management plans. For Oxycaryum cubense (Cuban bulrush), the monocephalous form allocated more resources to total biomass production and had inflorescence biomass peak during summer. In Lake Martin (Louisiana) and Orange Lake (Florida) (polycephalous form), inflorescence biomass peaked during the winter months. The difference in peak inflorescence timing should be a focus for management to prevent seed production for both flower types of O. cubense. Management of the monocephalous form should occur in late spring before seed production, whereas management of the polycephalous form could occur later in the growing season if inflorescence biomass was the target. Across all sites, O. cubense continued to grow into winter months (November to February) when most plant species senesce, suggesting a broader temperature tolerance that may allow it to spread outside its current range. These data also provided evidence that O. cubense does not store starch in high concentrations; therefore, management should focus on overall biomass reduction and preventing seed head formation, especially in the polycephalous form.

Introduction

Cuban bulrush [Oxycaryum cubense (Poepp. & Kunth) Lye] is an epiphytic invasive perennial plant that exploits other aquatic plants or structures for habitat and does not directly rely on belowground biomass for most of its life cycle (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). It is native to the tropical Americas but is now found throughout the southeastern United States (Bryson and Carter Reference Bryson and Carter2008; Bryson et al. Reference Bryson, Maddox and Carter2008). In the United States, both the multiple-head or polycephalous (Oxycaryum cubense f. cubense) and single-head or monocephalous (Oxycaryum cubense f. paraguayense) inflorescences are found (Bryson and Carter Reference Bryson and Carter2008; Bryson et al. Reference Bryson, Maddox and Carter2008). Oxycaryum cubense is stoloniferous, which allows for rapid, vegetative, short-distance spread, and it also reproduces sexually through single-seeded buoyant achenes that allow for long-distance water dispersal (Bryson and Carter Reference Bryson and Carter2008; Grippo et al. Reference Grippo, Fox, Hayse, Hlohowskyj and Allison2014; Watson and Madsen Reference Watson and Madsen2014). Previous research suggests seed viability in O. cubense is low (Bryson and Carter Reference Bryson and Carter2008; Watson and Madsen Reference Watson and Madsen2014). It relies on floating plants like water hyacinth [Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms] and giant salvinia (Salvinia molesta Mitchell) to serve as a substrate for germination and early establishment and to structurally support accumulating biomass (Bryson et al. Reference Bryson, Maddox and Carter2008; McFarland et al. Reference McFarland, Nelson, Grodowitz, Smart and Owens2004). The phenology, or the seasonal timing of critical life stages such as biomass allocation in O. cubense, is relatively unique compared with most aquatic plants, as it peaks in the colder months of the year (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023).

During a plant’s life cycle, resources such as nonstructural carbohydrates produced from photosynthesis are stored or used for critical functions such as growth (Chapin et al. Reference Chapin, Schulze and Mooney1990; Pennington and Sytsma Reference Pennington and Sytsma2009). Resource allocation is a fundamental aspect of a plant’s life stage and can be used to describe distinct events in a plant’s life cycle (Wersal and Madsen Reference Wersal and Madsen2018). Knowing when and where resources are being stored can offer valuable insight into the timing and efficacy of management and the potential recovery of plants after implementation of management techniques (Wersal and Madsen Reference Wersal and Madsen2018). Studies have investigated resource allocation of parrotfeather [Myriophyllum aquaticum (Vell.) Verdec.] and common reed [Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud.] and have provided valuable information on management timing based on weak points in a plant’s life history (Wersal et al. Reference Wersal, Cheshier, Madsen and Gerard2011, Reference Wersal, Madsen and Cheshier2013). Plant life history and resource allocation will vary seasonally due to several environmental variables, including light availability and temperature (Wersal and Madsen Reference Wersal and Madsen2018).

Light availability is the most important factor regulating aquatic macrophyte growth and is often positively correlated with temperature (Barko et al. Reference Barko, Adams and Clesceri1986). Seasonal fluctuations and latitudinal changes in photoperiod influence aquatic plant growth and can cause biomass accumulation to differ among populations. For example, E. crassipes growth is positively influenced by both air and water temperatures (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Holst and Rees2005). In Minnesota, curlyleaf pondweed (Potamogeton crispus L.) biomass peaks in May to June, followed by peak turion production in June, then senescence in July (Woolf and Madsen Reference Woolf and Madsen2003). In Mississippi, P. crispus grows year-round, with peak biomass occurring in February when water temperatures are lower and photoperiod is shorter (Turnage et al. Reference Turnage, Madsen and Wersal2018). Additionally, water temperature influences plant performance, especially photosynthetic rates (Pilon and Santamaria Reference Pilon and Santamaria2002). In general, as water temperatures increase, overall biomass of submersed macrophytes increases (Barko et al. Reference Barko, Hardin and Matthews1982; van Dijk and van Vierssen Reference van Dijk and van Vierssen1991; van Dijk et al. Reference van Dijk, Breukelaar and Gijlsrta1992). However, prolonged exposure to high water temperatures (>25 C) reduces photosynthetic rates (Barko et al. Reference Barko, Hardin and Matthews1982; Madsen and Adams Reference Madsen and Adams1989; Pilon and Santamaria Reference Pilon and Santamaria2002; Spencer Reference Spencer1986), propagule germination (Scheffer Reference Scheffer1998), and shoot elongation (Madsen and Adams Reference Madsen and Adams1988; Spencer Reference Spencer1986). Oxycaryum cubense is an epiphytic emergent plant, so both air and water temperature are likely important, as well as temperature effects on the plants that O. cubense uses for colonization.

In Mississippi, O. cubense biomass peaked (309.0 g dry weight [DW] m−2) during months with colder temperatures (8.4 to 15.8 C) and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) of 450 to 758 µmol−2 s−1 (November to February; Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). Weak negative correlations were found between total, emergent, and submergent biomass and water temperature and PAR (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). Energetically, O. cubense stored very little starch (3.7% DW), with peak storage occurring from August to September (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). While the aforementioned study provided initial phenological and resource allocation data on the monocephalous form of O. cubense, it was spatially limited and did not include the polycephalous form. Geographic distribution may influence phenological and resource allocation through plants being adapted to localized environmental conditions.

To date there are no data on O. cubense phenology outside Mississippi or on the polycephalous form. With regard to differences in morphology, the polycephalous form may have different allocation strategies when compared with the monocephalous form. For instance, the cost of reproduction in plants is high and usually causes an inverse relationship between reproduction and vegetative activity when more reproductive tissue is present (Obeso Reference Obeso2002). Therefore, the objectives of this research were to (1) expand the spatial extent of the previous phenology study (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023) and (2) investigate the phenological differences in O. cubense forms (monocephalous and polycephalous) over a 1-yr period in Lake Columbus (Mississippi, monocephalous form), Lake Martin (Louisiana, polycephalous form), and Orange Lake (Florida, polycephalous form). It is hypothesized that (1) O. cubense biomass will increase as air temperatures decrease as reported by Clarke et al. (Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023); (2) starch storage will be similar between the two O. cubense forms; and (3) there will be differences in biomass allocation based on inflorescence type.

Materials and Methods

Biomass Data Collection

A field study was conducted using established O. cubense populations at Lake Columbus near Columbus, MS (33.5341N, 88.491W), Lake Martin near Lafayette, LA (30.223127N, 91.90619W), and Orange Lake between Gainesville and Ocala, FL (29.458997N, 82.173167W). Plots in Lake Columbus were established by placing polyvinyl chloride (PVC) posts into the lake bed at the corners of each plot. Plot corners were then geotagged in case natural events (e.g., flooding) removed PVC posts. Lake Martin and Orange Lake plots were marked with plot centers that were also geotagged. Sites were placed in secluded areas that were less likely to be affected by disturbance or management. From October 2021 to September 2022, O. cubense was harvested monthly from two 0.04-ha plots in each waterbody. Visual percent cover of O. cubense and co-occurring species was estimated during each sampling event based on the area of the plot. At each site, 12 random samples were collected using a 0.1-m2 (33 by 33 cm) quadrat to determine O. cubense biomass. Within each quadrat and before harvesting, O. cubense height was measured from the water surface to the tallest plant. All living plant material (emergent, submersed, and inflorescence) was harvested by cutting biomass from the floating mat within the quadrat. Harvested samples were placed in labeled 3.79-L plastic storage bags, and stored in a cooler. If samples were too large for a single bag, then multiple storage bags were used and labeled accordingly.

Samples from all locations were then shipped to Mississippi State University, where the plants were separated into emergent (photosynthetically active ramets), submersed (stolons, roots, and non-photosynthetically active biomass below the water), and inflorescence tissues. Any visibly dead or decaying tissues were removed from the samples before drying and excluded from analyses. Sorted plant tissues were placed into labeled paper bags and dried at 70 C for 5 d in a forced-air oven. Once dried, biomass samples were weighed to determine biomass (g DW m−2) for each sample at each site for each month.

Environmental Monitoring

One Onset® HOBO® pendant (470 MacArthur Blvd., Bourne, MA 02532) was placed on a PVC pole 1 to 2 m above the water surface at each site to collect air temperature (C) and photoperiod every hour for the duration of the study. Any data that were unattainable due to weather events or equipment failure were supplemented with temperature data from nearby weather stations such as the MSU RR Foil Plant Science Research Station for Mississippi (33.470139N, 88.780028W), the Lafayette Regional Airport for Louisiana (30.203167N, 91.985831W), and the Gainesville Regional Airport for Florida (29.6917N, 82.276028W).

Starch Analysis

Oxycaryum cubense biomass was used to assess the seasonal allocation patterns of starch in emergent, submergent, and inflorescence tissues. Dried biomass samples from each site were composited into three groups of four (biomass samples 1 to 4 into tissue sample 1; 5 to 8 into sample 2; 9 to 12 into sample 3) to obtain three tissue samples for each plant at each sample location of every month (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023; Wersal et al. Reference Wersal, Cheshier, Madsen and Gerard2011, Reference Wersal, Madsen and Cheshier2013). Compositing samples ensured that there was enough tissue mass available for starch analysis.

Composited samples were milled using a Cyclone Sample Mill (UDY Corporation, Fort Collins, CO) and filtered through a #40 mesh screen (1 mm). Approximately 60 mg of ground sample was used for starch analysis. Starch extraction and determination were conducted via the amylase/amyloglucosidase method using a commercially purchased STA20 starch assay kit from Sigma Aldrich (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023; Haram and Wersal Reference Haram and Wersal2023; Wersal et al. Reference Wersal, Cheshier, Madsen and Gerard2011). Wheat and corn starch standards were included with the kits as 89% and 93% pure starch, respectively. Additionally, two sets of duplicate O. cubense samples were assayed per field site and per month to determine the reliability of starch data. Standard curves were developed to ensure that starch data were within the range of kit detection and to assess the relative accuracy of starch data. The precision of assays, as determined by the percent difference of duplicate samples, was 11.13% ± 1.23% standard error (SE). The standard curves had an average r2 = 0.98. Mean corn and wheat starch recovery was 94.75% ± 1.68% SE and 101.90% ± 2.24% SE, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Monthly averages for biomass, plant heights, and environmental variables (photoperiod and temperature) were computed for each plot. To better observe seasonal trends in biomass, a three-point moving average was calculated. A Kruskal-Wallis analysis was conducted on total, inflorescence, emergent, and submersed biomass and starch data to determine whether differences among locations existed. Linear regression analyses were used to determine relationships between environmental variables (photoperiod and air temperature) and plant metrics. All analyses were conducted at α ≤ 0.05 significance level using Statistix 10 (Analytical Software, 2105 Miller Landing Rd, Tallahassee, FL 32312 or SigmaPlot 12.5 (405 Waverley St, Palo Alto, CA 94301).

Results and Discussion

Total, inflorescence, and emergent biomass differed among the Lake Columbus, Lake Martin, and Orange Lake locations (P < 0.01). Submersed biomass also differed among states (P < 0.01), with Lake Martin (Louisiana) plant biomass greater than the other sites. Total biomass was greatest in Lake Columbus (Mississippi), where peak biomass was 600.71 g DW m−2 (± 37.76 SE) in October (Figure 1). Total biomass in Lake Martin peaked at 392.25 g DW m−2 (± 62.14 SE) in September (Figure 1), whereas Orange Lake total biomass peaked at 233.85 g DW m−2 (± 7.33 SE) in May (Figure 1). In a similar study on the monocephalous form in Mississippi, average peak total biomass was 309.0 g DW m−2, 290.0 g DW m−2, and 129.3 g DW m−2 in 2019, 2020, and 2021, respectively, and usually occurred in late fall or early winter months (November to January) (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). Low points of total biomass in Lake Columbus occurred from February to May (122.62 to 155.72 g DW m−2; Figure 1). The low point in total biomass from Lake Martin occurred between March and April (0 to 17.22 g DW m−2; Figure 1). Total biomass in Orange Lake was lowest from December to March (88.41 to 102.43 g DW m−2; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mean Oxycaryum cubense seasonal total biomass (g DW m−2) collected monthly from two sampling locations in Lake Columbus (Mississippi), Lake Martin (Louisiana), and Orange Lake (Florida) from October 2021 to September 2022.

Peak emergent biomass in Lake Columbus was 336.78 g DW m−2 (± 31.21 SE) in October (Figure 1). Peak emergent biomass in Lake Martin was 250.33 g DW m−2 (± 9.00 SE) in September, and peak emergent biomass in Orange Lake was 168.76 g DW m−2 (± 24.81 SE) and occurred in October (Figure 1). Peak submersed biomass differed among sites, with Lake Columbus, Lake Martin, and Orange Lake peaking at 258.79 g DW m−2 (± 71.62 SE), 76.63 g DW m−2 (± 1.78 SE), and 183.77 g DW m−2 (± 29.20 SE) in October, January, and May, respectively (Figure 1). Peak inflorescence biomass in Lake Columbus, Lake Martin, and Orange Lake was 19.53 g DW m−2 (± 0.68 SE) in August, 138.53 g DW m−2 (± 5.76 SE) in December, and 22.00 g DW m−2 (± 6.13 SE), in January, respectively (Figure 1).

Low points in emergent biomass from Lake Columbus occurred from February to April (53.43 to 88.99 g DW m−2), while emergent biomass in Lake Martin was lowest from March to April (0 to 12.00 g DW m−2), and emergent biomass was lowest in March to April (20.50 to 37.23 g DW m−2; Figure 1) from Orange Lake. Submersed biomass from Lake Columbus was lowest from April to May (35.23 to 41.00 g DW m−2; Figure 1), submersed biomass from Lake Martin was lowest from March to April (0 to 5.00 g DW m−2), and submersed biomass from Orange Lake was lowest (16.31 to 35.32 g DW m−2) from November to December (Figure 1). Inflorescence biomass was absent in Lake Columbus from February to April, whereas inflorescence biomass from Lake Martin was absent from April to July (Figure 1). Inflorescence biomass in Orange Lake was absent from February to September.

Oxycaryum cubense biomass observed in this study was generally lower than that of other common invasive aquatic plants. Eichhornia crassipes biomass typically ranges between 550 and 1,100 g DW m−2, with the main growth-limiting factor being freezing temperatures (Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Luu and Getsinger1993). Aboveground biomass in triploid flowering rush (Butomus umbellatus L.) peaked at just over 500 g DW m−2 (Marko et al. Reference Marko, Madsen and Sartain2015), and diploid B. umbellatus produced between 600 and 1,100 g DW m−2 (Gebhart Reference Gebhart2023). Total biomass of P. australis was recorded as being between 1,375 and 3,718 g m−2 (Wersal et al. Reference Wersal, Madsen and Cheshier2013). Total biomass of M. aquaticum was >500 g m−2 in a study conducted in Mississippi (Wersal et al. Reference Wersal, Cheshier, Madsen and Gerard2011). Although O. cubense biomass observed during the current study was, in general, greater than what was previously reported in Mississippi (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). Environmental factors such as air temperature and light availability influence plant biomass and can differ temporally.

Inflorescence biomass from Lake Columbus had a moderate and weak positive relationship with air temperature (r2 = 0.53) and photoperiod (r2 = 0.27; Table 1). There were no relationships between total biomass, emergent biomass, submersed biomass, and the environmental variables (photoperiod and air temperature) within the Lake Columbus population (Table 1). In a previous study on Lake Columbus, there were weak negative correlations found between total, emergent, and submergent biomass and water temperature and PAR in biomass samples collected from 2019 to 2022 (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). Plant height in Lake Columbus had a weak positive relationship with air temperature (r2 = 0.18; Table 1) which was similar to what was previously reported for O. cubense harvested in this lake (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023).

Table 1. Regression analyses for Oxycaryum cubense plant metrics and environmental factors from two sampling locations in Lake Columbus (Mississippi), Lake Martin (Louisiana), and Orange Lake (Florida) from October 2021 to September 2022

Oxycaryum cubense inflorescence and submersed biomass from the plants collected in Lake Martin had a moderate and strong negative relationship with photoperiod (r2 = 0.53 and 0.78, respectively) and submersed biomass had a strong negative relationship (r2 = 0.64) with air temperature (Table 1). There was no relationship between emergent biomass or plant height and the environmental variables for O. cubense in Lake Martin (Table 1). Inflorescence biomass in Orange Lake had a weak negative relationship with photoperiod (r2 = 0.31; Table 1). Plants growing in Orange Lake had a weak positive relationship between submersed biomass, air temperature, and photoperiod (Table 1). There were no relationships between total biomass and emergent biomass with the environmental variables in Orange Lake. Oxycaryum cubense height in Orange Lake had a negative relationship with photoperiod (r2 = 0.33).

Starch was not predominately stored in any one tissue during the study (<1.4% DW per tissue) regardless of sample site or inflorescence form. Total starch in the current study ranged from 1.4% to 3.0% (Figure 2) and is comparable to what was previously reported (3.2% to 3.7% DW) from populations in Mississippi (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). Total starch storage was different (P < 0.01) between Lake Columbus and Orange Lake populations. Emergent starch also differed (P < 0.01) between Lake Columbus and Orange Lake populations. Total starch content was low among all populations (2.0% to 2.8% DW) and peaked between October and February (Figure 2). Low points in starch accumulation or content generally occurred from May to September for all populations (0.4% to 1.0% DW; Figure 2). Inflorescence and submersed tissue starch did not differ among populations (P = 0.57). Starch storage in inflorescence tissues sampled from Lake Martin and Orange Lake was higher in winter months, while starch storage in inflorescence tissues from Lake Columbus was higher in the late summer (Figure 2); although concentrations never exceeded 1.2%. This does highlight potential physiological differences between the monocephalous and polycephalous forms.

Figure 2. Mean Oxycaryum cubense starch (%DW) from two sampling locations in Lake Columbus (Mississippi), Lake Martin (Louisiana), and Orange Lake (Florida) from October 2021 to September 2022.

Emergent starch content of Lake Columbus specimens had a weak negative relationship with air temperature (r2 = 0.43); there were no relationships with total and inflorescence starch (Table 1). Total, inflorescence, and submersed starch in Lake Martin specimens had weak negative relationships with photoperiod (r2 = 0.21 to 0.40) (Table 1). Total starch in Lake Martin had a weak negative relationship with air temperature (Table 1). Emergent starch in Lake Martin specimens was not related to environmental metrics (P = 0.73 to 0.77; Table 1). Starch in Orange Lake samples had weak to strong negative relationships between air and photoperiod with all tissues (r2 = 0.17 to 0.66) (Table 1).

Light duration (photoperiod) can have a strong influence on phenological timing of aquatic plants. In the current study, O. cubense biomass had a negative relationship with temperature and light. In Lake Columbus, light availability was reduced in the fall and winter months, when photoperiod ranged from 10 to 12 h, and increases in biomass corresponded with this lower light period. Oxycaryum cubense growing in Lake Martin and Orange Lake also had negative relationships with photoperiod, with increases in biomass occurring between 11 and 12 h of light, although biomass was lowest in Orange Lake. The exposure to a more intense and consistent photoperiod would occur in more southern latitudes, which may saturate photosynthesis at a faster rate.

One factor that plays a role in plant physiology is the use of photosynthetic pathways, which are important in how plants respond to differences in environmental variables such as temperature and light availability. Taxonomically, O. cubense is in the Oxycaryum clade of Cyperus that uses the C3 pathway (Larridon et al. Reference Larridon, Reynders, Huygh, Bauters, Vrijdaghs, Leroux, Muasya, Simpson and Goetghebeur2011). In general, C3 plants are more efficient photosynthetically across a broad temperature range than C4 or CAM plants, especially in cooler climates (Yamori et al. Reference Yamori, Hikosaka and Way2014). In environments where temperatures are cooler and where CO2 is elevated, C3 plants have a greater photosynthetic ability because of reduced photorespiration and enhanced light-use efficiency (Ehleringer and Cerling Reference Ehleringer and Cerling2002). The use of the C3 photosynthetic pathway may explain why O. cubense grows well in cold temperatures. Additional ecophysiological research is needed on O. cubense to better quantify its photosynthetic efficiency.

Depending on the growth form of an aquatic plant (i.e., free-floating, emergent, etc.), the effect of air temperature can vary (Dhir Reference Dhir2015). Temperatures between 20 and 35 C are considered optimal for most aquatic plant species (Santamaria and van Vierssen Reference Santamaría and van Vierssen1997). Oxycaryum cubense growth and resource allocation were higher when average temperatures ranged from 9.4 to 18.4 C, which corresponded to early fall and winter months. In Mississippi O. cubense was growing with several other species, including E. crassipes, during the warmer months of the year (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). On average E. crassipes had biomass values of 300 to 560 g DW m−2 between June and September. During this same time period, O. cubense biomass was only 30 to 90 g DW m−2 (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). As air and water temperatures declined in fall and winter, the other plant species senesced, or died, and likely released O. cubense from competitive interactions, as O. cubense biomass during the winter months increased to 129.3 to 309.0 g DW m−2 (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Wersal and Turnage2023). Seasonal changes in environmental factors lead to shifts in species composition throughout a growing season.

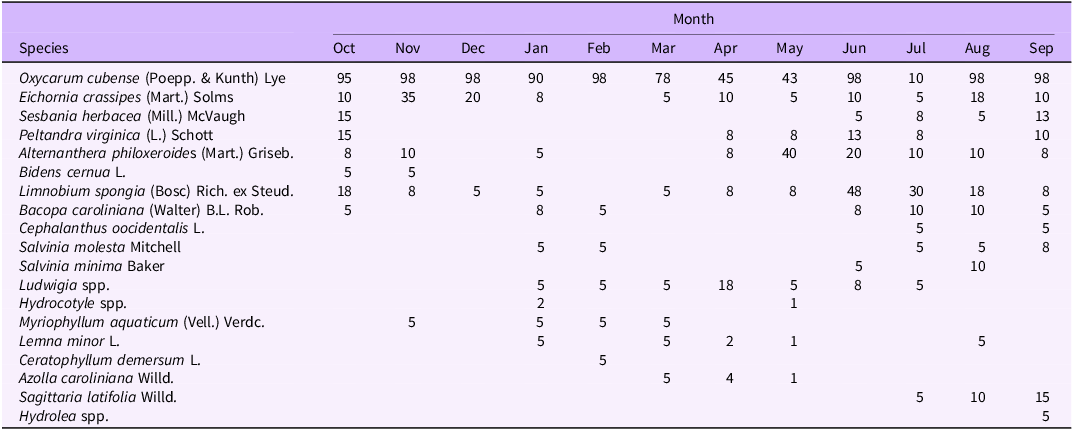

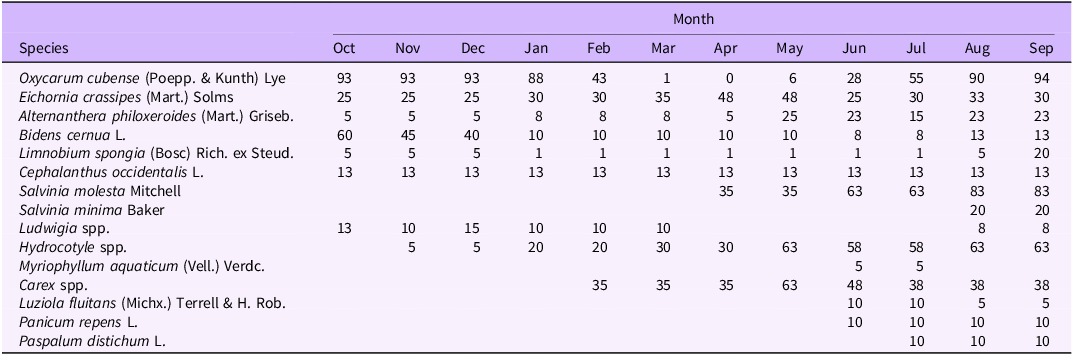

Oxycaryum cubense visual percent cover from October to February was 43% to 100%, which also corresponded to times of peak biomass (Tables 2–4). During this time period, the cover and species richness of other aquatic plant species were low. In general, O. cubense cover was lower when cover of other aquatic plants increased, typically March to August. In months when O. cubense percent cover was lower, floating species or creeping species such as alligatorweed [Alternanthera philoxeroides (Mart.) Griseb.], Ludwigia spp., American frogbit [Limnobium spongia (Bosc) Rich. ex Steud.], and E. crassipes were prevalent (Tables 2–4). In Orange Lake, O. cubense cover was 100% in 8 of the 12 mo, which is indicative of a longer, more stable growing season with a lack of seasonal cues to trigger phenological traits. Even though this study did not directly measure species interactions, it is possible that O. cubense is susceptible to shifts in species composition, ecophysiological differences, or the need for other species to reach a critical mass in order to support the O. cubense tussock.

Table 2. Average percent cover of plant species between both plots in Lake Columbus (Mississippi) from October 2021 to September 2022

Table 3. Average percent cover of plant species between both plots in Lake Martin (Louisiana) from October 2021 to September 2022

Table 4. Average percent cover of plant species between both plots in Orange Lake (Florida) from October 2021 to September 2022

Overall, the results from this study indicate that there are some phenological and resource allocation differences between the monocephalous and polycephalous forms of O. cubense. The polycephalous populations in Louisiana and Florida achieved peak biomass in November to January and had higher inflorescence biomass. The monocephalous form allocated more resources to total biomass production, demonstrating a difference in resource allocation between the two inflorescence types. The differing phenology and higher resource allocation to inflorescence biomass in Louisiana and Florida may be due to competitive stress. Both Florida and Louisiana are ranked first and second for introduced species, including aquatic species (USGS 2023). Many of the introduced plants are also rapid colonizers (Gérard and Triest Reference Gérard and Triest2018; USGS 2023). Interspecific competition can cause niche differentiation, such as differing phenology (Uchida et al., Reference Uchida, Fujimoto and Ushimaru2018). Additionally, sexual reproduction is also hypothesized to be more beneficial than clonal propagation for plants growing at high density, because it promotes dispersal; it is known that O. cubense utilizes sexual reproduction for a similar purpose (Zhang and Zhang Reference Zhang and Zhang2007).

Oxycaryum cubense does not store starch in high concentrations; therefore, management should focus on biomass reduction during spring with repeat management to deplete energy reserves and limit reproduction. It is important to prevent seed production in the polycephalous form, as this form of O. cubense allocates more resources to flower production earlier in the year compared with the monocephalous form. Monitoring programs will need to be developed for O. cubense based on its broad temperature range. Based on accumulated degree day modeling, O. cubense has base temperature thresholds of −6 C, −3 C, and −2 C for Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida populations, respectively (Squires et al. Reference Squires, Turnage, Wersal, Mudge and Sperry2024). The models suggest O. cubense has a tolerance to lower air temperatures, which could permit survival in moderate winter conditions, and the low base temperature thresholds suggest this species may be capable of expanding its invaded range to cooler climates beyond the southeastern United States (Squires et al. Reference Squires, Turnage, Wersal, Mudge and Sperry2024).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Nature Conservancy, and Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission for allowing access to some of the field sites. We also thank Josh Long, Walt Maddox, Esther St. Pierre, Garret Ervin, Anna McLeod, Bram Finkle, and Graham Lightsey from Mississippi State University for technical assistance in field sampling and sample preparation. We thank Michael Durham of the University of Florida Center for Aquatic Invasive Plants for technical assistance in Florida. We thank David Sexton of the Louisianna State University Ag Center and Daniel Hill of the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries for technical assistance in Louisiana. Finally, we thank Max Gebhart and Hunter Kelzenberg from the Aquatic Weed Science Lab at Minnesota State University for sample preparation and analysis. This article is a contribution of the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station and the Mississippi Cooperative Extension Service. The article was reviewed in accordance with U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center policy and approved for publication. Citation of trade names does not constitute endorsement or approval of the use of such commercial products. The content of this work does not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. government and no official endorsement should be inferred.

Funding

The research was supported by the Aquatic Plant Control Research Program, U.S. Army Engineer Research & Development Center (USAERDC) under cooperative agreement W912HZ2120036.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.