INTRODUCTION

States in the role of conquerors can and do resort to conscription, forced labour, and resettlement of their own subjects, and act as slave raiders and downright subjugators towards people of the areas conquered. The state can act as employer towards old and new subjects; and it can, as a redistributor, enforce labour services as taxation in kind, or the necessity to work in order to be able to pay taxes and fulfil their obligations towards the polities. Lastly, states provide legislation and adjudication and thus act as arbiter. This paper aims to present the Chinese state in the transition from the Ming to the Qing dynasties in all of those roles that impacted on the ways in which people were expected to extract, produce, and render service for themselves and their families, for private employers, and for the sector under direct dynastic control.

The present study will portray three salient points of political impact on labour relations: the formation of the Manchu Banners in the period roughly 1600 to 1650; the increase in unfree labour relations in the form of bond service in Central and Southern China, a process that continued between 1500 and 1650 and gradually waned in the eighteenth century; and finally, the most negative way a conquering state can influence labour relations: by annihilation or expulsion of a population from its territory, as demonstrated in the case of the Dzunghars in the 1750s and 1760s. This is where shifts in labour relations due to political activity can be shown most clearly. Numerically, these three processes involved a comparatively small segment of the population. The much greater part experienced, if anything, changes due to reasons that hinged on market mechanisms and especially on demography. The relatively peaceful period after the consolidation of the Qing dynasty in 1683 and, consequently, the population growth in the eighteenth century can be considered an achievement of Qing political rule that prepared the ground for changes in labour relations from more self-sufficient to more market-related forms. Yet, since this impact on labour relations was quite indirect, and ran counter to the professed Qing ideal of a calmly self-sufficient, rural populace, it will be treated here as a backdrop to more direct government and polity intervention in the three samples discussed. This evidence will be set into the capital-coercion paradigm outlined by Charles Tilly. Although this dichotomy was intended mainly as an explanatory tool for an interpretation of European historical experiences, Tilly also applied it to China, drawing on G. William Skinner’s analysis of administrative and economic centres.Footnote 1 Tilly transposed Skinner’s insights to his own framework by identifying the administrative centres as belonging to the realm of top-down coercion, while the markets and economic centres arose from the bottom-up and largely self-regulatory activities of local elites and merchants.Footnote 2 Yet, Skinner’s and, as a consequence, Tilly’s evidence was based largely on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when the interplay of coercive means and capital incentives differed from those during the period of dynastic decline in the Ming and the rise of the Qing studied in this article.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Manchus, who established the Qing dynasty and ruled China from 1644 to 1911, were a confederation of several groups who defined themselves as the descendants of the Jurchen, an earlier North Asian confederation that had once conquered North China in the twelfth century. Important steps in the formation of Manchu identity and political power were the unification of several Jurchen tribes by Nurhaci (1559–1626), who declared himself their leader (khan) around 1600, and the grouping of these people first into smaller units, the companies (niru), which, in turn, were subordinated to larger divisions, the banners (gusa).Footnote 3 The original Jurchen population was meant to be entirely included in those banners, thus breaking or superseding their previous affiliations to clans or tribes. Banners were socio-military units, in the sense that entire households belonged to them – not only fighting men, although the designations for these units are military.Footnote 4 At the end of the formative phase (until c.1615) the banners consisted of about 60,000 households.Footnote 5 In 1616, due to the increase in the number of people who belonged or were forced to affiliate, four more banners were added. Around 1642, the largest groups of non-Jurchens who had been incorporated into the banners, i.e. Han Chinese (the so-called Chinese armies or “Chinese-martial” hanjun) and Mongols, were separated from the Manchus, so that there actually existed twenty-four banners, organized along lines of ethnic affiliation.Footnote 6

In later conquests, companies of members of further ethnic groups, such as the Russians from the defeated border fort of Albazin on the Amur, Dzunghars who had capitulated, and Muslims from Turkestan, were added to the banners. The Jurchen under Nurhaci conquered the Liaodong region to the east of the Liao River (1621–1626), where conflicts with the Han Chinese arose. Several policies to appease and accommodate the Chinese were applied both by Nurhaci and his successor Hong Taiji (1592–1643). Since these strategies pertain to labour relations, they will be discussed separately.

To mention just the landmark years of the Jurchen expansion into China, the ethnic self-designation “Manchu” was chosen in 1635, the dynasty was named Qing (“the pure”), and a Chinese-style capital with government institutions was established at Shenyang in 1636.Footnote 7 At least since about 1618, when Nurhaci declared war on the Ming, it had been the ambition of Jurchen/Manchu rulers and their Chinese councillors to force the Ming to accept Manchu dominance in the Manchurian home territory. In the course of a bloody conquest, Central and Southern China was first allotted as a kind of feudal territory to three military leaders affiliated with Chinese-martial banners. However, when these aspired to exclusive rule over all China, their fiefs were seized from them. The conquest of Taiwan and its incorporation into the Qing empire in 1683 marked the point of consolidation of Qing rule over China. From then on, until the mid-eighteenth century, expansionary wars were waged especially on the northern and western periphery. Among these, the struggle against the Dzunghars, a Mongolian confederation that wanted to establish an empire of its own, peaked in the 1750s and 1760s and resulted in a high death toll.Footnote 8

LABOUR RELATIONS IN THE FORMATIVE PROCESS OF THE MANCHU ETHNIC GROUP: JURCHENS BEFORE THE INTRODUCTION OF THE BANNERS

For the Jurchen/ManchuFootnote 9 people and the conquered Han Chinese, Mongolians, and Dzunghars, among many others, the expansion of the Qing brought about complex changes in social relationships – not least in labour relations .

Figure 1 Overview Jurchen-Manchu Territory.

As Crossley remarked, at the outset a khan was a “keeper of slaves”; regardless of their language, customs, or habitat, these slaves owed him total service and received protection and symbolic or real familiarity in return.Footnote 10 In this sense, the Jurchen population was expected to pledge allegiance to Nurhaci and, as such, to become formally his subjects in the sense of “servants” or even “slaves”. In theory, this would imply labour relations of the obligatory labour kind. For the entire population this type of “slavery” was formal rather than factual,Footnote 11 but real slavery in the sense of treating people as saleable commodities also occurred in Jurchen society.

Traditionally, the Jurchens lived in a combination of economic pursuits including hunting, fishing, plant gathering (especially ginseng), animal breeding (especially horses), and, since around 1500, increasingly also agriculture, which can be characterized as semi-nomadic or “limited nomadism”.Footnote 12 To be precise, three distinct zones of tribal activities can be defined. The “Wild Jurchens” in the north on the Amur and Ussuri rivers were mainly hunters and fishers, with additional pig-raising and non- or half-sedentary agriculture. The Haixi Jurchens east of the Nonni River and in the Sungari River region experienced the strongest Mongolian influence, practised agriculture in the east, and raised cattle in the west. The Jianzhou Jurchen in the south, on the Mudan River and next to the Changbaishan Mountains, bordering on Korea, were hunters and fishers, gathered freshwater pearls and ginseng roots, farmed, and produced textiles.

Material exchange with the Chinese had been organized since the early fifteenth century. Tribute to the Ming court was delivered in a system that foresaw that neighbouring peoples who had accepted Ming domination were to present particular natural products at certain intervals. They would receive gifts in return, often more valuable than those they had brought, and were allowed to trade along their itinerary. In the course of the fifteenth century, some of the Jurchen tributary missions appeared in the Ming capital in numbers bordering 800 or 900, or even 1,000.Footnote 13 This led to restrictions on the number of people entitled to engage in tribute trade, and to conflicts among those who wished to make the journey and enjoy the benefits of this type of trade.Footnote 14

Established in the early fifteenth century by the Chinese authorities, horse markets in the border region were another form of material exchange. Moreover, Jurchen local products were sold and exchanged for Chinese tea, silk, cotton, rice, salt, and agricultural tools. Unofficial trade was also conducted with Korean, Mongol, and Chinese merchants,Footnote 15 mostly to obtain weapons, ironware, and copper cash.

Elliott outlines a three-tier system of social relations, with elites (irgen) directly responsible to the tribal leaders, later the khan; semi-free Jušen, who were obliged to submit tax and perform obligatory work, including military duties, for the tribal leaders; and unfree serfs or slaves, who were dependants of household heads (aha, booi, or booi aha).Footnote 16 There was a certain ethnic fluidity in the system in that not all the Jušen (and certainly not all the unfree group) were Jurchens/Manchus; they also included Chinese, Mongols, and Koreans. Both the upper and middle strata could own serfs or slaves. During the early Ming, it was the enslaved captives taken during warfare on the Jurchen-Ming and Jurchen-Korean borders who mostly performed the agricultural work in the Jurchen villages.Footnote 17 The slave owners could dispose of them as they wished, resell and even kill them.Footnote 18 This points to a linkage of military engagement for raiding and acquisition of manpower, and the predominant delegation of agricultural activities to the captives, at least in the earlier phases of the polity. Although scholarly opinions about the exact period of transition to an economy based on stronger engagement in agriculture vary, the annexation in 1621 of the Liaodong area is most often considered a starting point for a system of agriculture supervised by the banners, where ordinary banner people would work in the fields.Footnote 19 Jurchen households typically consisted of five to seven members, and, in addition, a number of slaves who were not relatives, but people from other ethnic groups. Before the formation of the banners, the households would form units that hunted and gathered food together, and in the case of warfare they were grouped into larger temporary companies. After the introduction of the banners these sometimes very small communities were placed under a unified command that could eliminate previous loyalties and impose new ones.Footnote 20

According to Roth Li’s perceptive analysis, the border and tribute trade caused a clearer division between wealthy and poor people within the Jurchen tribes, especially in southern Manchuria, where more trading opportunities could be realized than in the north, where group hunting was still the major economic activity. With wealth, the political aspirations of group leaders became more evident, as did internal competition and warfare. It is highly plausible that in the course of the sixteenth century Jurchen merchants desired a stronger administration that could guarantee the security of their transactions.Footnote 21 This trend may well have led to the rivalry among Jurchen leaders, the emergence of Nurhaci, and the institution of the banners, which cut through previous tribal affiliations and connections among the Jurchen.

Before the introduction of the banners shortly after 1600, Jurchen labour relations can be characterized, in the terms of the Collaboratory, as reciprocal and tributary, with the first traces of commodification. For the reciprocal type of labour, labour relations 4a (leading household producers), 4b (household kin producers), and 5 (household kin non-producers) applied to the Jurchen hunters, fishers, and gatherers. The sources are not quite clear as to whether the produce traded at the markets and on the tribute missions was sold and bought by specialized merchants; at any rate, a certain degree of commodified labour (labour relations 12a, self-employed leading producers, and 12b, self-employed kin producers) can be assumed.Footnote 22 The enslaved agricultural workers mentioned above correspond to labour relation 6 (reciprocal household servants and slaves), which is defined as “subordinate non-kin (men, women, and children) contributing to the maintenance of self-sufficient households”.Footnote 23

LABOUR RELATIONS AMONG THE JURCHENS AFTER THE INTRODUCTION OF THE BANNERS (c.1600)

The banners formed the basic socio-military unit of the Jurchen people under the rule of Nurhaci and his successors. As to why this type of organization was introduced, the historiography points as a rule to the concentration of power in the person of Nurhaci. The new units gradually superseded the traditional smaller tribal or clan communities. Historical records of the foundation of Manchu rule do not spell out a clear causality of why the companies (and later the banners) were established, but it gives the context, “[Nurhaci] assembled the growing masses of adherents and grouped them into companies of 300 people […] earlier, when our people went on warfare or on a hunt, it was not calculated how many participants there were, but they all set out following their tribe or fortified settlement”.Footnote 24 According to this narrative, companies and banners were formed to optimize and professionalize military and hunting operations and to homogenize manpower into equal units. At the same time, like the previous clans and villages, they encompassed the entire population, including women, children, and dependants, and were permanent structures rather than hunting or raiding parties that dispersed after the spoils had been divided. Especially after the establishments of the first banners, the “adherents” – not all of them of their own volition – also encompassed subjugated Chinese, Mongolians, and Koreans, as well as Jurchen groups from the northernmost periphery that had been out of reach earlier, but now partly came into the expansionary orbit of Nurhaci and his followers. The number of people involved is estimated at about 100,000 taxed males before 1615, a figure that rose to at least several hundreds of thousands during the phase of western expansion between 1616 and 1625.Footnote 25 This is generally held to be the entire population.

After the banners were introduced, the middle strata (Jušen) formed their core. Basically, they were agricultural producers whose land was taxed, as well as hunters and gatherers. In peacetime, they essentially supported themselves and their households, working for a subsistence living and for the market. When taking part in campaigns, they were supported by the polity, especially in the period of Hong Taiji’s dominance (1626–1643).Footnote 26 This support came in the form of grain stipends, the so-called “walking grain provisions” (xingliang). The labour relations of the active fighters belong to the tributary mode, labour relation 8 (obligatory labourers: those who have to work for the polity). When not campaigning, the banner people relied on traditional ways of supporting themselves and their families, and on war booty.Footnote 27

The time span between 1618 and 1636 saw initiatives to make the Jurchens and the Chinese under their control adapt to each other, and this pertained, too, to labour relations. After a relatively relaxed relationship in the 1610s, when both parties viewed the other as more or less equal,Footnote 28 the situation following the first attempts of the Manchus to conquer Liaodong in 1618 grew tenser. Integrationist and separationist moves on the part of Jurchen rulers followed, and the Chinese rebelled. In the integrationist phase, Nurhaci ordered that in some regions Jurchen conquerors should live together with the Chinese in their households, on equal terms.Footnote 29 This policy was resented by the Chinese, and after a series of rebellions and the (alleged?) poisoning of resident Jurchens the Chinese were reorganized and distributed to Manchu officials in a status resembling slavery.Footnote 30 Nurhaci’s successor Hong Taiji, a usurper in need of Chinese support, placed the Chinese who had surrendered to his rule under their own officials, had them registered, and aimed at realizing equality between the Chinese and Jurchens.Footnote 31

Under Nurhaci, an effort was also made to attract Han Chinese people from the region west of the Liao River to settle in the newly conquered Liaodong, promising them a life as “free and equal landowners”, stressing that “All will equally be the khan’s subjects and will live and work the fields on an equal basis.”Footnote 32 Yet, in the process of conquest in Liaodong, there is clear evidence that some of the Chinese previously living there were enslaved, with a gradation from downright chattels (aha) to bondservants (booi niyalma). Roth points out that originally slaves were people captured in battle, but a document from 1624 also reveals a case in Liaodong where households with property of less than a certain amount of grain were enslaved, while those who possessed more were set free.Footnote 33

Until the Manchu established themselves as an imperial dynasty in Peking, large numbers of non-Manchu people were made soldiers for the conquerors, as a hereditary obligation. After the conquest, some of them rose to senior positions in the civilian ranks. This distinctive new rank and new type of labour relation emerged largely due to the fact that the ruling group of Manchus needed the administrative and linguistic skills of the Chinese and occasionally other non-Chinese people to govern China.

The period between Nurhaci’s rise around 1600 and the conquest of the Ming territory in 1644 thus brought about changes in tributary labour relations due to socio-political change in the organization of the banner people and their dependants. It was made possible by the Jurchen/Manchu appropriation of power due to military superiority and the ensuing prerogatives for recruiting unfree labour, first in a region considered peripheral by the Ming, and eventually in North China south of the Great Wall.

CHANGES IN LABOUR RELATIONS AFTER THE MANCHU CONQUEST OF CHINA

After the conquest of Peking, and subsequently of all of China, bannermen garrisons were established in the capital and in most provincial capitals. In these garrisons, the bannermen households, including their retainers (slaves and bondservants), received stipends and were thus no longer producers, but instead rendered hereditary military service. In the terminology of the Collaboratory, this still corresponds to tributary labour of type 8 (those who have to work for the polity), but with the difference that this was now remunerated on a permanent basis. The payment for the bannermen in the garrisons was mainly monetized, being paid monthly in silver, and in addition grain allowances were given in kind.Footnote 34 The banner people were also granted land in the newly conquered territories, to be tilled by dependants (bondservants or slaves). Yet, banner people as a rule opted not to till the land personally, but to sell it in order to pay for other expenses.Footnote 35 Since, due to fertility, the number of banner people and their dependants south of the Great Wall kept rising, to a degree the government could not afford, several campaigns were started to repatriate banner people to Manchuria. The idea was to have them earn their own living, opening up land for agriculture, but this was not greatly successful.

Research on the social history of the banners has also offered further estimates of their numbers and the level of state revenue necessary for their upkeep. Elliott quotes a figure of between 300,000 and 500,000 adult males, excluding bondservants, in the Eight Banners at the time of conquest (1644), with about forty-three per cent being Manchu, twenty-two per cent Mongol, and thirty-five per cent Chinese.Footnote 36 For the early eighteenth century this might have risen to between 850,000 and 1.6 million bannermen. Including women, children, and bondservants, this may have added up to between 2.6 million and 4.9 million people. At this time, about half of the active bannermen were employed in Peking to guard the capital, while twenty per cent were employed in Manchuria and thirty per cent in the garrisons in China proper and on the borders.Footnote 37 The ratio of active bannermen to dependants (family members, bondservants, and slaves) varied from garrison to garrison, with highs of ten and lows of five dependants to one salaried bannerman.Footnote 38 In the terms of the Collaboratory, by no means all people in the banners worked in tributary labour relations. On the contrary, the labour relations of family members and bondservants were reciprocal; bondservants and slaves belonged to labour relation 6 (reciprocal household servants and slaves: subordinate non-kin), and the family members of banner people and of the bondservants and slaves who did not work as servants themselves belonged to labour relation 5 (household kin non-producers) and 1 (non-working) (for the children and elderly).

Moreover, tributary labourers for the polity did not only imply military labour for defence. The maidservants in the palaces, for instance, were drafted from the banners and worked between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five or thirty. This corresponds to labour relation 8 (those who have to work for the polity). Moreover, the palace in Peking had a certain number of positions for daily workers in casual jobs in palace or garrison maintenance (sula). The workers recruited as sula belonged to the banners and bondservant companies, and thus had a status that should have entitled them to receive lifelong state support for their subsistence. Yet if, in addition, they took on daily maintenance work in return for modest remuneration, this can be understood as commodified work since this type of work offered scope for extra income when funds were not sufficient to feed the worker and his family. For the palace institution employing these workers, the Imperial Household Department (Neiwufu), this arrangement allowed for flexibility in the event of immediate need, for major ceremonies for instance. Since there was a – restricted – market for labour of this type, it could be argued that this was of labour relation type 18.3 (wage earners employed by non-market institutions, time rate payment).Footnote 39 Outside the palace precincts, another group of workers for the banners were those who laboured on the imperial agricultural estates. The historiography refers to about 11,000 worker positions engaged on these domains in the vicinity of the capital, where grains, cash crops, fruit, and vegetables were grown, cattle were raised, and horses bred. More worked on estates in Manchuria. Their personal status was either one that resembled serfdom (labour relation 10), since they were forbidden to leave the estates, and the commitment was hereditary. These workers, mostly captives and convicts, owned no means of production. Other farmers had commended themselves to the imperial house, but retained the right to self-management and even to sublet their land. They had to pay rent and provide particular services in addition, such as gathering certain mushrooms, herbs, or ginseng. Yet, whereas the Imperial Household Department demanded mainly labour service from the serf-like workers, the main exigency from the farmers who had commended themselves, and who as a rule oversaw the performance of the others, was payment in silver rather than their labour in agriculture. The overseers were registered as bondservants and at least theoretically forbidden to return to their previous status as ordinary citizens.Footnote 40

Military campaigns were frequent during the expansionary phase. When not on campaign, the bannermen in their garrisons who were entitled to receive a stipend were supposed to guard the garrison and maintain their military preparedness. Formal collective drills were assigned in two three-month periods per year, and for the rest of the time soldiers were expected to train their skills, especially by bow-shooting from horseback, and by hunting, which was deemed the most befitting occupation (except warfare) for a bannerman.Footnote 41 In addition, banner people were entitled to a large share of lucrative military and civilian administrative positions. The number of these assignments was quite out of proportion to the actual proportion of the population whom the banner people represented.Footnote 42 Yet, with the banner population increasing over time, and despite the trend to create jobs for them by all means, a rising number of banner people were registered as “idle” (sula) and could receive only temporary work assignments. In the palace in Peking alone, between fifty and a hundred temporary assignments for the sula were envisaged per day.Footnote 43

In the context of the impact of state policies, it is important to note that estimates for 1730 based on both the historiography and archival records suggest that perhaps as much as between twenty-one and twenty-five per cent of the annual state budget was allocated to support the banner system, the constituents of which formed a strategically very important elite comprising just two per cent of the entire population of the Qing empire.Footnote 44 Moreover, according to Elliott’s calculation, most of the expenses for the banners were used to feed not the officers and soldiers but family dependants and horses.Footnote 45 Military tributary labour in the banners was thus unfree, but advantageous and privileged if the soldiers could obtain their wages. This was not always the case. Crossley mentions that most of the garrison populations “did not receive stipends, but lived as the dependents of those men between the ages of 15 and 60 who were eligible for, and lucky enough to actually secure, the payments”.Footnote 46

It was a political choice to maintain this elite group of fighters, who, until the restrictions on their occupations were lifted in 1863, were not supposed to work for subsistence or for the market.Footnote 47 The reasons for this were evidently the trust that the Qing rulers and the Imperial Household Department as the core court institution placed in persons of the same region of descent, often defined as enlarged family. In the case of the Han Chinese members of the banners, what counted was the proven loyalty at a certain critical period in the transition from the Ming to the Qing. Evidently, this was an uneconomic way of keeping an army, the dependants of which were continuously increasing due to demographic reasons, which led to poverty among many of its members. Like other contemporaneous states in the world where standing armies were maintained,Footnote 48 the Qing state had to shoulder a huge financial burden in order to maintain its privileged Eight Banner fighters. The intention of Qing rulers was to protect the distinction of the ruling elite, even if this did not seem to be economically rational. This was all the more the case since the banners were not the only Qing army.

LABOUR RELATIONS IN THE OTHER QING ARMY: THE GREEN STANDARDS

Apart from the political decision to support the Eight Banner Army, the Qing sustained an army of paid Han Chinese soldiers. This was, as Ulrich Theobald and I have shown, the second large shift in labour relations in the service of the state.Footnote 49 The Green Standard Army, which was recruited mainly from Ming divisions who had deserted, consisted of professional soldiers working in commodified labour relations. This employment was intended for a lifetime. Soldiers’ sons turning sixteen had the right, not the obligation, to serve in the army.Footnote 50 As to the size of the Green Standards compared with the Eight Banners, the rule-of-thumb figure is 600,000 and 200,000 men respectively.Footnote 51 The Green Standards commanded not only land, but also marine forces. As to combat power, the numerical ratio between banner and Green Standard soldiers serving on the battlefield was typically 1:10,Footnote 52 but in some wars, especially against the Dzunghars, banner troops were deployed in a larger proportion.

Previously, the Ming army had a corvée military service, and the transition to the professional Green Standard Army can be qualified as one from tributary to commodified labour.Footnote 53 Yet, already during the Ming era (1368–1644), powerful and resourceful private households, and even military and civilian officials, privately hired soldiers, so that this transition should be seen as gradual.Footnote 54 It hinged upon the weakening of state power in the latter half of the Ming dynasty and the increasing financial liquidity due to the silver influx during this period. In the expansionary phase of the Qing, military conscription was not inflicted upon the Han Chinese population, and apart from the Green Standard Army free wage labour was used also for transport workers and experts, especially for arms producers, who were not continuously employed in the army.Footnote 55 Thus, in contrast to the Ming, whose standing army consisted of military households entitled to land and which were supposed to feed themselves, in the case of the Han Chinese army the Qing resorted from their inception to commodified military labour.

In Tilly’s sense, the above setting points to a tendency towards the capital-intensive rather than coercion-intensive path for recruitment in the military sector in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In the Jurchen/Manchu case, in the pre-conquest era the government profited both from tributary military and agricultural labour in the new territories of Liaodong. Yet, after the rule of the Qing had been consolidated south of the Great Wall, although the labour of the banner soldiers was of a tributary nature, that of the Green Standard Army was not. Moreover, both constituted a small proportion of the population that was overwhelmingly engaged in agriculture in reciprocal and commodified labour relations.

WARFARE WITH THE DZUNGHARS: DESTRUCTION AND EXPULSION OF A LABOUR FORCE

During the period of Qing expansion between the 1690s and the 1780s, frequent wars were waged against adversaries north, west, and south of the empire. All of these battles involved high death tolls. The longest conflict was against the contenders for primacy in the huge steppe empire of the Dzunghars. These semi-nomadic groups of Oirat Mongols, whose power base lay in present-day Xinjiang (see Figure 2), had not accepted Qing supremacy. Like the Jurchen, and at about the same period, their leaders acquired weapons technology, and resettled in their own territory captives from ethnic groups well versed in agriculture (mostly those later referred to as Uighurs; that is, Muslim Turkic-speaking non-nomadic people), who were coerced to work in tributary labour relations. The Dzunghars exploited the mineral resources of the region, controlled trade revenues, and tried to combine various groups of the Oirat Mongols to consolidate their power.Footnote 56 The Dzungharian population worked mostly as animal herders, practising nomadic pastoralism. As such, their labour relations correspond to those of the Jurchen before the conquest, working in reciprocal labour relations 4a, 4b, and 5. Like the Jurchen, the Dzunghars employed war captives both for animal herding,Footnote 57 but also for agriculture.Footnote 58 This was unfree labour, and since the slaves had no right to leave, the corresponding labour relation is 11. The sources hardly warrant a quantification of the people engaged in commodified labour relations. Figures given in the literature quoting total sales from eight Dzungharian trade missions in 1752 suggest the possibility of a partly commodified economy.Footnote 59

Figure 2 Qing expansion into the Dzungharian territory.

The wars with the Qing empire were first fought between 1689 and 1696, when the Dzunghar leader Galdan (1644–1697) was defeated. The final conflict, between 1752 and 1758, was a retaliatory campaign for the insubordination of a potentially dangerous Dzungharian rival. As a result, a region corresponding to present-day Northern Xinjiang was depopulated. In an account published in 1842, the historian Wei Yuan quotes a figure of several hundred thousand households (600,000 people, according to Peter Perdue), of which forty per cent died of smallpox, twenty per cent fled to Russia and Kazakhstan, thirty per cent were killed by the Qing army in battle,Footnote 60 and the remaining women, children, and the elderly were enslaved and given over to serve in Manchu and Mongol banners.Footnote 61

The area was resettled with military farms, a pattern in use in Chinese empires since the Han dynasty (206 bce to ad 220). Here, at first, Chinese soldiers and exiled convicts, but also resettled Uyghurs from the Tarim Basin, worked mainly in tributary labour relations to secure the upkeep of the garrison forces, initially about 40,000 men (c.1760). Half of them were Mongols and Manchu banner people, and half were Chinese soldiers.

As a result of the escalating conflict between the Qing and the Dzungharian empires, a harsh cut in terms of the size of the labour force ensued. Decimation was an intentional policy, and the practice of subjugation of the remaining population had direct consequences on labour relations, causing an extreme shift from predominantly reciprocal to tributary relations. This could hardly have happened had it not been for the war and subjugation.

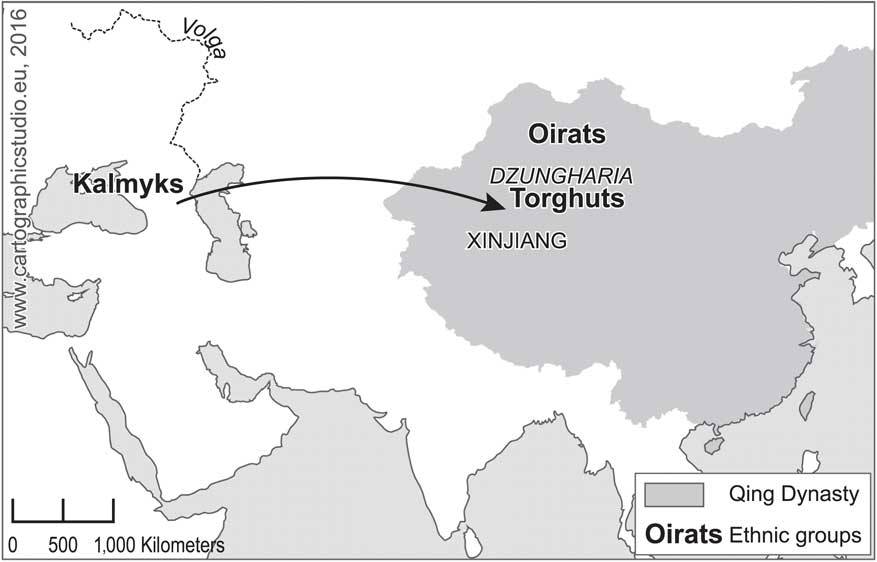

Interestingly, shortly after this culmination of Qing expansion into central Asia, ethnically related groups also resettled in what had previously been Dzunghar territory. As Dmitry Khitrov explains in his contribution to the present Special Issue, the Kalmyks had fled from Dzungharia in the first half of the seventeenth century. Like the Dzunghars, they belonged to the Oirat group, but formed a distinct subgroup, the Torghuts. These people searched for more open pastures in the north-west, their migrations in the 1620s and 1630s taking them as far as the Lower Volga. Yet, after the experience of being subjected to coerced military service in Russia, about 150,000 of them remigrated to Dzungharia in 1771, and between 50,000 and 70,000 were settled in Northern Xinjiang (Figure 3).Footnote 62

Figure 3 Kalmyk remigration.

UNFREE LABOUR SOUTH OF THE GREAT WALL IN THE LATE MING AND EARLY QING

While between the early 1600s and the mid-seventeenth century, the far north thus experienced a reconfiguration of labour relations depending upon status and ethnicity, and empire-wide the armed forces were converted from a corvée army in the Ming to the commodified Green Standard Army during the Qing, simultaneously in central China and in the south a change in labour relations emerged that can be characterized as an increase in unfree labour.Footnote 63 This trend started from about the 1550s in many regions in China, but it is especially well documented for the central and southern provinces. Among the reasons that led to the immiseration that brought about this particular turn, an increase in state expenditure on warfare and consequently higher taxation, bad harvests, and little state support for the destitute were most important.Footnote 64

In a recent article, Claude Chevaleyre cites the classic study by Ho Ping-ti,Footnote 65 who assumed that about one per cent of the Ming population were of a lower legal status than the commoner population. Chevaleyre concludes that this may have meant 700,000 to two million people around 1600, most of whom were probably bondservants, but more exact figures cannot be ascertained.Footnote 66

There was a variety of forms of this type of unfree labour: hereditary and non-hereditary; some of these servile labourers were more bound to the household of the masters, both in the countryside and in cities, others worked the fields. The service obligation tied them not to the land, but to the master, in whose household register the servants were usually included as dependants. Ownership of bondservants was not reserved for the nobility; as a rule, the masters were commoners. Harriet Zurndorfer has described the wide variety of possible arrangements, pointing out that although the bondservants belonged to the lowest legal category, they could own and dispose of land and exploit other bondservants.Footnote 67 Variegated as the category was, there were several ways in which people could become bondservants: through purchase, adoption, marriage (if a free man married a bonded woman, his status and that of their children would be commuted to that of bondservants), debt bondage, coercion, and self-commendation.Footnote 68 In spite of the negative consequences for personal freedom, in some cases people entered into bond service in order to escape criminal indictment or to garner the protection of an influential family for their own advancement. Not all types of bond service implied permanent servitude and completely forsaking one’s previous property.Footnote 69

Although the search for protection, and perhaps even the hope of working as a manager or overseer of agricultural estates or in wealthy households as a “luxury slave” or “brazen servant” (haonu), might have prompted some to commend themselves, in most cases bonded labour simply meant toil and exploitation. The recorded bondservant rebellions in Middle and South China confirm this assumption. Mixius has analysed these movements, which contributed to the upheaval at the end of the Ming dynasty. He assumes that the unrest was caused by the immediate great economic and social pressure on the bonded people.Footnote 70 There are records of about one hundred such incidents involving between several dozen and up to 5,000 participants between the 1620s and the 1660s.Footnote 71 It needs to be stressed that the Qing armies, when they met with rebellious bondservants on their conquest in 1644 and 1645, crushed these insurrections and for the time being opted to restore law, order, and the previous property and work relations rather than to propose and realize immediate change.Footnote 72

The loss of life due to the violence seen during the southern expansion did reduce the entire labour force. However, this was not a deliberate policy, in the sense of extermination, even if the consequences were accepted by the conquerors. In general, if appeasement and accommodation were actively sought after (and this was certainly not always the case), it was targeted at elites rather than at the population. In 1660, the banner people were forbidden by government order from accepting any further self-commendations of the Han Chinese population. The reason was most certainly not an emancipatory concern for those who were willing to serve in unfree labour conditions, but that the stipends of the banner people were not high enough to pay for an increasing number of servants.Footnote 73

During the eighteenth century, the broad tendency towards emancipation, and the rise of tenancy and wage labour in agriculture rather than unfree labour, has been discussed in the historiography.Footnote 74 Bond service gradually disappeared in most regions during the eighteenth century.Footnote 75 Demography and market forces may have played a more important role in this respect than state policies, since there was an available labour force in many Chinese regions due to the increase in population, and a labour market existed.Footnote 76 This becomes evident if legislation and legal cases are considered. Concerning the arbitration of the Qing state in labour issues, major turning points were the gradual acknowledgement that cases involving crimes committed by short-term hired labourers should be treated similarly to those of ordinary, free people.Footnote 77 Previously, the status of hired workers resembled that of a bondservant, because economic dependence implied legal inferiority. After 1735, the discrimination linked to the quasi-bonded status of long-term hired workers who were engaged for a year or longer was also gradually eased.Footnote 78 This means that status inequality expressed in legal codification as to the value of the life of a master versus a bonded servant no longer applied in its harshest form. In judicial practice, the proceedings for cases including homicide (when masters killed servants) had to be reported to the central government and appeared in the routine memorials presented by the provincial authorities to the Ministry of Justice.Footnote 79 This is not an example of active intervention in labour relations by the government. Rather, it can be interpreted as an acknowledgement of a change in the social valuation of labour; the government followed, and did not take the lead. Yet, the mere fact that the government did take it onto itself, even if formally (backlogs were great), to arbitrate cases between workers and employers, and later also dealt with issues of wage labour, shows a perspective of the functions that governments can and did take in mediating in labour disputes and labour relations.

At the same time, it is important to bear in mind that wage labour both in agriculture and in the production of commodities did not account for a large percentage of the population.Footnote 80 By far the largest economic sector, which covered the greatest part of the Chinese population, was self-sufficient agriculture, with slowly increasing commodification. Here, the impact of the state and tributary labour relations was slightest. As Tilly observed, below the level of the district governments “even the mighty Chinese Empire ruled indirectly via its gentry”.Footnote 81

CONCLUSION

How can the government actions outlined above be interpreted in the framework of Charles Tilly’s paradigm of capital and coercion? Looking at the larger picture, the implications of the capital-coercion nexus for labour relations consist of a clearly conceivable coercive element in the form of military recruitment by banner formation north of the Great Wall during the expansionist phase of Jurchen/Manchu rule. From the perspective of the Qing government, this also had a more paternalistic side of concern for the well-being of the ethnic core group and its dependants. Both the rebellious Dzunghars and the Kalmyks who had returned from the Volga region experienced more or less extreme forms of coercion by decimation or by resettlement and forced change of occupation and lifestyle. The factor of “capital”, if applied to labour relations, pertains to the commodified types. The trend to commercialization during the Qing proved to be irreversible, even if gradual: at least the rights of tenants and wage labourers were raised to the same level as those of commoners in the legal codes.

Returning to the question of which types of labour relations were actively shaped by the expanding Qing empire and which were subjected more to other influences, as defined by the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations (economic, demographic, social and geographic mobility, urbanization, technological), the formation of the banners stands out clearly. This type of state intervention related to a (post-conquest of China) small percentage of the population, but it changed the configuration of military labour relations in a distinct manner. The unfree labour relations of the bondservants in conquered China, and the status of hired workers (and tenants), were arbitrated and acknowledged ex post facto, rather than directly impacted. In this field, economic institutions and evolutionary change played a more important role.

Tilly’s ideas about the specific Chinese combination of capital and coercion derived from a relatively stable setting with a landowning gentry and merchants representing capital and state power embodying coercion. Looking at the period of the enormous upheavals in the course of the dynastic transition and consolidation renders a more dynamic view of a part of the world where the compounded capital-and-coercion mode had been in existence in different combinations but as least as long as in Europe.