Introduction

In recent historical literature on social policy and the “welfare state” growing interest can be detected in what has been called “transnationalism”, meaning “contacts, coalitions and interactions across state boundaries that [are] not directly controlled by the central policy organs of government”.Footnote 1 In the literature on “transnational history”Footnote 2 it is claimed that social policy, like the policy made in many other fieldsFootnote 3 by national, regional, and local government officials in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was not, or at least not always, carried out in isolation, whereby solutions to social problems had simply to be dreamed up out of thin air. Rather, possible remedies for the “Social Question” were often widely exchanged, discussed, weighed, and compared in transnational networks of national experts, civil servants, and politicians from various countries before they were implemented in their national, regional, or local contexts.

Chris Leonards and Nico Randeraad, for example, identify an “epistemic community in the making” of transnational experts in the field of social reform, experts who in the second half of the nineteenth century “define[d] for decision-makers what the problems [were] and how they [were] to be solved”.Footnote 4 Pierre-Yves Saunier and colleagues observed that several decades later networks of municipal activists, scientists, civil servants, and the like from various European countries regularly met to discuss common social, political, and economic problems and their possible remedies.Footnote 5 Likewise, in the same period, Christian Topalov and Ingrid Liebeskind Sauthier identified the transnational development of labour statistics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries which – when it was thought that those statistics could be utilized to predict recurring cycles of unemployment – helped pave the way for the development of the first state-run or state-subsidized unemployment insurance schemes both in France and Great Britain.Footnote 6 Finally, Julia Moses noted the effects of international contacts between governments when, in the late 1890s and early 1900s, governments tried to adapt the national social insurance schemes they already had in place for compensating workplace accidents to accommodate one another so as to afford protection to their citizens in foreign countries.Footnote 7

Yet, while in the historical literature growing awareness of the importance of transnational and international “policy transfer” and “policy learning” can be observed, interest in transnational welfare schemes is largely missing. Perhaps its absence can be explained by the fact that in the mainstream literature on the history of European welfare states that history is usually interpreted as a process of “scaling up” the geographical level at which care for the needy was organized. According to that interpretation, until the end of the nineteenth century the local religious community, occupational group, and perhaps government authorities were responsible for welfare provision. From the 1880s, in many countries, that task was gradually transferred to actors at the national level – government, labour unions, and employers’ associations – as part of larger processes of centralization and nation-building.Footnote 8

While it is obvious that at least in most northern and western European countries the further development of the national welfare state meant the end of many local welfare institutions, that development should not be thought of simply as a “scaling-up” process. This article argues that in some cases the creation of the institutions of national welfare states meant quite the opposite of scaling up – that is, the “scaling down” of the geographical level at which welfare provision had been organized. It describes and analyses the development of the mutual unemployment insurance funds established by Dutch labour unions for their members, which until the 1930s were largely accessible to the numerous foreign workers employed in the Netherlands. Many foreign workers became fund members not by applying individually for membership, as their Dutch peers had done, but through arrangements whereby union insurance funds in various European countries granted benefit entitlements to each other's members by means of bilateral or multilateral agreements. Until the late 1910s such agreements were signed and effectuated without hindrance from national governments and in that sense were truly transnational social “policy” relations, or networks. They were continued into the 1920s despite growing interference by the Dutch government in the functioning of union funds, but during the 1920s and 1930s the bonds between Dutch and foreign insurance funds were gradually broken. This article investigates why.

The agreements between union insurance funds will be looked at primarily from the Dutch perspective, although analysis of them is based on data sources from various countries. The Dutch perspective is fruitful because the Netherlands was among the last European countries in which transnational alliances between union funds were actively terminated by the national government. While in the interwar period in many European countries the alliances were blocked by national governments’ attempts to “nationalize” the labour market,Footnote 9 the Dutch government continued to tolerate them until World War II, which opens the possibility of investigating fund alliances and the factors that facilitated and hindered them, both in the Netherlands and abroad, throughout the entire pre-war period.

The article unfolds into four sections. The first describes the rise and functioning of labour union insurance funds in the Netherlands and of the regulatory interventions by Dutch local and national governments in the 1910s and 1920s. The second section analyses the emergence of agreements on the exchange of benefit entitlements between Dutch and foreign union funds, their forms and significance, and the attempts by the Dutch government to regulate the phenomenon. The third section focuses on three branches of industry – diamonds, metallurgy, and textiles – in which, until the 1930s, the agreement route had some significant relevance. It will show that from the late 1920s the flow of new foreign members to union insurance funds gradually dried up. The various causes of that development are explored in the fourth section.

Labour Union Unemployment Insurance Funds In The Netherlands

As in many other European countries, in the Netherlands voluntary mutual funds were established by labour unions in the late nineteenth century to insure their members against all sorts of social risks. The funds, which were non-commercial and run by labour union officials exclusively, were successors to the local mutual insurance schemes of the guilds that had dominated the artisan crafts in most Dutch cities since the Middle Ages. After the legal abrogation of the guild system in the early nineteenth century and the entrance of commercial companies into the insurance market, many such insurance schemes had disappeared, but the rise of “modern” labour unions in the last three decades of the nineteenth century gave insurance a new impetus. By the end of the nineteenth century about 15 per cent of the Dutch labour force participated in one or more insurance arrangements against the financial risks of sickness, invalidity, old age, and death.Footnote 10

Until then, mutual insurance schemes to combat the financial risks of unemployment remained rare, especially since experts considered unemployment insurance too risky.Footnote 11 By 1906 only about 19,000 workers – about 17 per cent of all union members and hardly 1 per cent of the Dutch dependent labour force – had joined a union unemployment insurance scheme.Footnote 12 That changed in 1906 when the Amsterdam City Council decided to establish a special subsidy fund for the local labour union unemployment funds. Funds could in principle request a subsidy of 75–100 per cent of the benefits they provided if they fulfilled a number of conditions.Footnote 13 Over the next 6 years, 31 municipalities followed the example of Amsterdam, mostly in the densely populated western provinces of the country.Footnote 14 The municipalities’ efforts to preserve and stimulate labour union funds were on the whole successful. Not only did the number of fund members in the Netherlands rise from 19,000 to almost 80,000 in barely 6 years, municipal support encouraged many labour unions that had not yet established a fund to organize new ones. By 1914 the total number of unemployment funds had risen to more than 770, while by that time more than 40 per cent of the funds’ members belonged to municipally subsidized funds.Footnote 15

In those early years of local government interference, the subsidy schemes were particularly advantageous for the insurance funds of Social Democratic labour unions. They were better represented than their Roman Catholic and orthodox Protestant competitors in the urbanized regions of the country where most of the first subsidy schemes were established, and since, at the time, their national organization was far more advanced than that of the Roman Catholic and orthodox Protestant unions it was easier for the local Social Democratic unions to reinsure with a national sector fund in order to comply with municipal regulations concerning the solvency of their insurance schemes. As a result, in 1914 the number of Social Democratic union members insured against unemployment was more than twice as high as in Roman Catholic and six times higher than in the orthodox Protestant unions. In the “pillarized” Dutch society taking shape in the period – characterized by vertical divisions along denominational or ideological lines – the availability of a sound unemployment insurance fund would increasingly become an important “selling point” in the competition among the various unions to attract members.

Meanwhile, the Social Democrats in Parliament made a determined effort to involve the national government in the support of union unemployment insurance. In 1908, during a fierce ideological debate on the causes of unemployment and the national government's role in combating its consequences, the Social Democrats, in collaboration with progressive Liberal and Confessional MPs in the Lower House, forced the Confessional coalition cabinet to install a Royal Commission to investigate the subject.Footnote 16 In its final report, published in 1914, the Royal Commission, chaired by the Progressive Liberal MP Willem Treub and in which the main labour unions, employers’ associations, and political parties were represented, advocated national government subsidies for unemployment benefits provided by union funds – the “Ghent system”.Footnote 17 The Royal Commission's advice would be adopted by the national government only a few months later as Word War I had started and the country faced peak unemployment rates – although, since the Netherlands remained neutral, it was not involved in the war.

In order to prevent union funds from collapsing under the huge influx of unemployed workers Treub, the former chairman of the Royal Commission and now Minister of Labour,Footnote 18 convinced his colleagues in the new Liberal coalition cabinet to support a huge rescue operation. In a circular of August 1914 Treub encouraged municipalities to establish a local subsidy fund and promised a 50 per cent national treasury reimbursement of local subsidies.Footnote 19 Two years later, this Treub Emergency Regulation (Noodregeling-Treub) was replaced by a permanent scheme, the 1917 Unemployment Benefits Decree (Werkloosheidsbesluit-1917), aimed at preserving union funds in the long run by stopping the subsidy of benefits but supporting members’ contributions – the “Danish system”.Footnote 20 Under the 1917 Unemployment Benefits Decree, total payments by the national government and the municipalities equalled 100 per cent of the contributions, and, again, each paid half the costs.

As a result of the establishment of the national subsidy schemes, over a period of 4 years the number of municipalities participating in those schemes rose from 33 to more than 700, or almost 70 per cent of the total number of Dutch municipalities. The increase in the number of insured workers was also spectacular, rising from 78,000 early in 1914 to 398,000 in 1918. By the end of 1919 almost 80 per cent of all Dutch union members, amounting to 19 per cent of the dependent labour force, were insured against the financial consequences of unemployment (see Figure 1). The national subsidy schemes caused the numbers of insured workers from all denominations to grow enormously, but those of the Roman Catholic and orthodox Protestant funds grew the most: between 1914 and 1920 membership in Social Democratic union funds increased fivefold, in Roman Catholic and orthodox Protestant circles the numbers grew almost tenfold.Footnote 21

Figure 1 Labour union unemployment funds in the Netherlands: number of fund members (n x 1,000), coverage of labour union membership (% of total membership), dependent labour force (% of total dependent labour force), and unemployment rate (% of labour force), 1900–1940. Sources: Labour union members in 1906 and 1910: Siep Stuurman, Verzuiling, kapitalisme en patriarchaat: Aspecten van de ontwikkeling van de moderne staat in Nederland (Nijmegen, 1983), p. 153; in 1914–1922 and 1924–1940: Ernest Hueting, Frits de Jong, and Rob Neij, Naar groter eenheid: De Geschiedenis van het Nederlands Verbond van Vakverenigingen 1906–1981 (Amsterdam, 1983), pp. 62 and 84. Membership of labour union unemployment funds in 1900 and 1902: estimates; in 1904–1940: Kuijpers and Schrage, “Squaring the Circle”, p. 97; registered unemployment: CBS, www.statline.cbs.nl, retrieved 1 July 2007.

For the union funds, government support had its price. In exchange for subsidies, the national government required the funds to fulfil a number of regulatory requirements and strengthened its supervision over them by means of a new bureaucratic apparatus. At the top of the hierarchy was the Minister of Labour, who as a rule interfered personally only when fundamental matters were at stake. The day-to-day implementation of unemployment insurance policy was delegated to a section of the Ministry of Labour, the State Authority for Unemployment Insurance and Employment Mediation (Rijksdienst der Werkloosheidsverzekering en Arbeidsbemiddeling [hereafter RWA]). Though the RWA was rather small it was very active in the regulation of union funds, especially after 1921. By means of circulars it imposed many regulations on them covering all kinds of matters – from the format they had to use to draw up their statistics to the stocks and shares they were allowed to invest their reserves in.Footnote 22 By doing so, the RWA forced the funds to adapt more and more to the national government's unemployment policy, “leading in the direction of uniformity and the centralization of unemployment insurance”.Footnote 23

In the course of the 1920s, the national government even made an attempt to transform the union fund “system” into a national and compulsory unemployment insurance scheme, administered and funded by the labour unions and employers’ associations. However, the attempt failed due to reluctance on the part of the labour unions to tolerate employers’ interference with what the unions considered “their” funds, and the employers’ refusal to contribute financially to the new insurance. Until after World War II employers would not be involved in any way in unemployment insurance. Meanwhile, in the economic crisis of the 1930s the financial and organizational involvement of the national government with the insurance system was expanded even further in order to prevent the labour funds from collapsing as ever more workers lost their jobs.Footnote 24

It might be expected that the growing interference of the Dutch national government with unemployment insurance in the interwar period would have been accompanied by a gradual exclusion of foreign workers from the national unemployment insurance systemFootnote 25 – but that was not so. In the same period, in countries like Great Britain and Germany, the “nationalization” of the labour market after World War I and national state intervention in welfare arrangements made it almost impossible for foreign workers to join the national unemployment insurance system.Footnote 26 However, the same process in the Netherlands did not prevent foreigners from joining the labour union unemployment insurance funds, at least not until the mid-1930s and then not for all categories of foreign workers. As will be shown in the following sections of this article, in the first three decades of the twentieth century many Dutch labour unions facilitated unemployment insurance fund membership for foreigners working in the Netherlands by making special arrangements with unions abroad. After World War I, such practices were regulated by the Dutch national government, but that does not seem to have hindered the special arrangements.

Foreign Workers and Union Unemployment Insurance Funds in The Netherlands

In about 1900, non-Dutch workers accounted for only 1.2 per cent of the dependent labour force in the Netherlands, yet from 1900–1930 that percentage almost tripled, to drop again to about 1 per cent in the 1930s and 1940s. In the period under consideration – the 1900s to 1940s – the great majority of foreign workers were German or Belgian. Many were cross-border workers, men and women working in the Netherlands, living in Germany and Belgium. They were employed in the coal mines of south Limburg or the ceramics factories in Maastricht in the south-east, the textile industry of Twente in the east and Brabant to the south, or in agriculture. In the early twentieth century many German women came to the Netherlands to work as domestic servants, while Poles, Italians, and Slovenes were recruited by mining companies having difficulty finding enough suitably skilled Dutch workers.Footnote 27

Until World War II membership of many labour union unemployment insurance funds was open to foreign workers, who could become members individually simply by applying for membership. Before the establishment of the national subsidy scheme in 1914, fund boards were largely free to set their own regulations concerning membership of foreigners, and many boards treated foreign workers just like any other applicant, which in some cases even meant that foreign workers who became union members were obliged to join the union's unemployment insurance fund. Even before World War I, some of the municipalities that had established subsidies for the local union funds required those funds to make an exception for cross-border workers from Germany and Belgium. In order to guarantee effective supervision of benefit recipients, those municipalities obliged fund members to live in the municipality or in one of the neighbouring Dutch municipalities, since local civil servants had no authority to supervise unemployed foreign fund members living in Germany or Belgium.Footnote 28

After the establishment of national subsidy schemes for union funds in 1914 and 1917, the exclusion of cross-border workers was gradually made obligatory for all union funds. The Treub Emergency Regulation (1914) had stated that only workers who “live outside, yet in the close vicinity of the municipality” were eligible for membership of funds, meaning that all long-distance cross-border workers were excluded. Four years later, however, the RWA issued an explicit guideline which stated that those “who work in this country but live abroad and regularly return to their country are not entitled to be accepted by a [subsidized] unemployment fund”.Footnote 29 Forced by the RWA, in subsequent years union funds one after another excluded cross-border workers from membership by changing their by-laws.Footnote 30 Indeed, cross-border workers remained ineligible for fund membership in the Netherlands until World War II, despite the fact that in 1932 the Dutch government signed the Unemployment Convention of the International Labour Organization (ILO), accepting the principle that member states which had signed the Convention should grant workers from other members of the Convention the same entitlements to unemployment provision as their own citizens, regardless of where they happened to live.Footnote 31

As well as applying individually for fund membership, foreign workers had a second option, although it was available only to those who had belonged to a union unemployment insurance fund in their home country immediately prior to arriving in the Netherlands. Such workers could become members of a Dutch fund if that fund had an agreement with the individual's fund in their home country to accept each other's members automatically. The great advantage of that option for foreign workers was that they retained benefit entitlements built up in their home country, and so did not have to endure as long a waiting period as other new members. In most branches of industry the agreements between Dutch and foreign union funds probably preceded Dutch national state intervention in union unemployment insurance and consequently they were very diverse. However, when in 1917–1918, by virtue of the new 1917 Unemployment Benefits Decree, the by-laws of labour union funds were required to be formally approved by the Minister of Labour in order to qualify for subsidy, a way had to be found to apply formal regulation to existing transnational practices. After some experimentation involving exchanges of multiple drafts among the Minister, the RWA, and the labour union boards, in 1918 the Minister came up with a standardized formula that read:

As for persons who, coming from abroad, have until four weeks prior to joining the [Dutch, subsidized] fund been a member of the unemployment fund of an organization with which the association [the Dutch union fund] has signed an agreement, and who by virtue of the agreement have become a member of the association, the length of time they have been a member of the unemployment fund of the foreign organization and the number of weeks they have paid contributions will count in calculating the duration [of the waiting period], provided they can sufficiently prove to the board that they have met all obligations towards the abovementioned fund.Footnote 32

This standard formula was subsequently imposed on the funds to be included in their by-laws, even on funds that did not yet have an agreement signed with any foreign fund. In the same year, the Minister issued a guideline stating that all agreements with foreign union insurance funds should be approved by him before they could become effective, which implied that the Dutch fund too had to provide him with a copy of the foreign funds’ by-laws. By so doing the Minister tried to prevent Dutch funds from signing agreements with foreign funds whose regulations were overly different from the Dutch ones.Footnote 33

Number and types of agreements

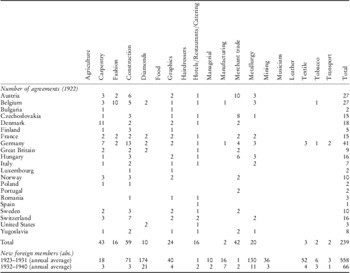

In 1922 the RWA published the first overview of the agreements (repeated only in 1927), which listed at least 239 agreements approved by the Minister between Dutch subsidized union funds and foreign funds in 26 different countries and in 12 branches of industry (see Table 1).Footnote 34 Two types of agreement can be identified in the list. The first type concerned agreements in which national labour unions belonging to an international union organization collectively recognized the entitlements of each other's unemployment insurance funds. In the early 1920s, seven such agreements existed between national members of international unions in the diamond, graphic, metallurgical, and construction industries. All the same, this type of agreement was problematic, since in many cases it was based purely on a collective declaration at an international union organization congress, while since 1918 the RWA had required insurance funds to produce exact details of their agreements and of their partners’ insurance regulations (see above). That is most likely why, by 1927, only one collective agreement was still recognized by the Minister.Footnote 35

Table 1 Number of agreements, by country and sector (1922), and foreign workers utilizing agreements, by sector (averages 1923–1931 and 1932–1940).

Note: The categorization of branches is derived from the official statistics of the RWA.

Sources: Agreements, by country and sector: RWA, Verslag, 1919–1922, pp. 150–160; number of foreign workers utilizing agreements: ibid., 1923–1940.

The second type of agreement concerned bilateral arrangements between Dutch and foreign funds on the mutual recognition of entitlements under each other's unemployment insurance funds, and they were far more common than the collective agreements just described. Of all Dutch unemployment funds active in 1922, about one-third had signed between two and eight such bilateral agreements. Clear concentrations can be observed in the bilateral agreements that Dutch funds signed with foreign funds. More than one-quarter of all bilateral agreements were signed with unions in neighbouring Germany and Belgium, about one-half with unions in a second ring of countries around the German and Belgian borders, and the rest with unions in more distant countries, ranging from Finland in the north to Bulgaria in the east and Spain in the south. Agreements were signed even with labour unions in the United States, and in the late 1920s with an Australian fund. In the period 1923–1930, on average three or four new agreements were signed between Dutch and foreign unemployment insurance funds each year.Footnote 36

The agreements were distributed by no means evenly among all Dutch labour union funds. More than three-quarters concerned agreements between a foreign and a Dutch Social Democratic fund (see Tables 2 and 3), and by 1922 the Social Democratic unions had signed agreements with unions in virtually all European countries in ten out of nineteen branches in which Dutch unions had unemployment insurance funds. Much more limited were the activities of the orthodox Protestant and Roman Catholic union funds, which had signed agreements with unions from a more limited number of European countries and in only six sectors. Interestingly, the orthodox Protestant and Roman Catholic unions had agreements with unions almost exclusively in countries where Christian Democratic unions played an important role, such as Austria, Belgium, France, and Germany. That probably explains, at least partially, the limited number of agreements orthodox Protestant and Roman Catholic unions had signed, since, unlike in Social Democratic circles where international labour union organizations had already been active since the 1890s, mature European networks of Christian Democratic organizations would not begin to develop until the 1920s.Footnote 37

Table 2 Orthodox Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Social Democratic union unemployment insurance funds: number of agreements with foreign funds (1922, absolute) and number of new foreign members using the agreement route (1929, absolute), by country

Sources: Number of agreements: RWA, Verslag, 1919–1922, pp. 150–160; number of new foreign members: ibid., 1929, p. 233.

Table 3 Orthodox Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Social Democratic union unemployment insurance funds: number of agreements with foreign funds (1922, absolute) and number of new foreign members using the agreement route (1929, absolute), by sector.

Sources: see Table 2.

Number of foreign workers using the agreements

The number of agreements did not necessarily reflect the number of workers who actually made use of any of the agreements to preserve their benefit entitlements. Unfortunately, in the period under consideration no records were kept of the total number of foreign members,Footnote 38 because clearly the funds themselves felt no need to discriminate between Dutch and foreign nationals in their membership records. When the national government began to interest itself in the subject in the early 1920s it succeeded in gathering information only on the annual number of new foreign members using the “agreements route”. However, when we compare those figures with the annual numbers of new Dutch fund members we might conclude that in the 1920s they followed more or less the same pattern (see Figure 2). If we further assume that the relative numbers of new foreign and Dutch union members reflect those of the total, we might even make a rough estimate of the average total number of foreign members who had used the agreements route to join a Dutch fund in 1923–1929: in fact it was about 2,500, or 0.8 per cent of total union unemployment fund members.Footnote 39

Figure 2 New membership of labour union unemployment funds: new Dutch and foreign members (n) and registered unemployment (% of labour force), 1923–1940.

Sources: New members: RWA, Verslag, 1923–1940; registered unemployment: www.statline.cbs.nl, retrieved 17 May 2010.

That number was not evenly distributed over the various branches of industry, countries, and labour union funds. If we take an average annual number of fifty new foreign workers using the agreements route in the 1920s as a threshold, in the 1920s only four branches of industry are relevant: diamonds, metallurgy, textiles, and construction. If we keep the same threshold, the number of relevant countries is similarly limited, for only Belgium and Germany “delivered” substantial numbers of new members. Finally, reflecting the number of agreements signed, Social Democratic union funds were the only ones that substantially used the agreements option to accept foreign members, although with one exception: the textile industry, in which the Roman Catholic union fund actively accepted foreign workers too (see Tables 2 and 3).

How did agreements between Dutch and foreign funds come about, and how did they function? To answer that question, in the next section I shall analyse three branches of industry in which the agreement route had some relevance at least until the 1930s, those being the diamond, metallurgical, and textile industries. For practical reasons, construction is left out of the analysis, since foreign workers using the agreements route in that sector were dispersed over many unions for specialized crafts, which allowed only a few isolated individuals annually to join their unemployment insurance funds. The analysis of the genesis and functioning of the transnational exchange of benefits in the three sectors is based on numerous sources, which for various reasons contain at best only fragments of information on the agreements and on the workers who used them. As a consequence, to various degrees the three reconstructions are incomplete, especially for the period after 1934.Footnote 40

Transnational Insurance in The Diamond, Metallurgical, and Textile Industries

Diamond industry

The labour union engaged in the most durable transnational partnership, at least as far as the Dutch were concerned, was the ANDB (Algemeene Nederlandsche Diamantbewerkers Bond), the General Dutch Diamond Workers’ Union, established in 1894.Footnote 41 The feasibility of benefit entitlements exchange in the sector was fostered by the fact that as early as about 1910 unemployment insurance had reached a relatively high level of development in the diamond industry, especially in Belgium and the Netherlands.Footnote 42

In addition, the viability of transnational partnerships was furthered by the highly globalized level of trade the diamond industry had attained by about 1900, with hotspots in Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, South Africa, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA. Labour mobility across borders was therefore quite common. For example, in the main Belgian diamond centre of Antwerp in 1910, 3,000 of the 14,400 local diamond workers were of foreign origin, most of them Dutch (1,700).Footnote 43 Finally, the feasibility of entitlement exchange was fostered by the relatively small size of the branch, a high union density, and the close family networks involved. At its pre-World-War-II peak in the early 1920s, there were about 22,000 diamond workers in the Western world, roughly 95 per cent of them union members, and the majority were almost certainly of Jewish origin. In the diamond world, jobs in the trade were often passed down within families.Footnote 44

Figure 3 Members of the Belgian union of diamond workers (ADB) and visiting foreign delegations. Photograph taken on the occasion of the ADB's thirtieth anniversary in front of the union's building in Antwerp.

Collection IISH

In the diamond industry the idea of transnational unemployment insurance went back to 1894, when the Dutch ANDB and Belgian diamond unions agreed at the official International Diamond Workers’ Congress in Antwerp that the establishment of insurance schemes for their members should be a common endeavour.Footnote 45 Three years later, unions from Paris and the French-Swiss Jura Mountains joined the international network and its insurance plans, receiving official backing when in 1905 the Universal Alliance of Diamond Workers (UADW) was established. By then the Diamond Workers’ Protective Union of America (essentially New York City) had joined their ranks, while the German diamond workers’ unions, mainly from Westphalia, would join two years later. The new Alliance was thereby transformed into the representative of virtually all organized diamond workers in the Western world,Footnote 46 with as its central objective “to form some sort of labour cartel that, by means of international cooperation, had a decisive say in the determination of wages and labour conditions”.Footnote 47 The collective recognition of each other's members’ unemployment insurance entitlements was part of that strategy. Thus in the “Articles of Association” drawn up at the establishment congress in Paris Alliance members agreed that “it is necessary that members moving from one centre to another and provided with certificates to show that they were in good standing with the organization in the place where they came from, should immediately enjoy all rights and benefits in the new centre”.Footnote 48

In the following years, that engagement was maintained by the associated unions, at least those with a viable insurance fund, namely the ANDB and Antwerp unions, which together represented approximately 80 per cent of all Alliance members, and the diamond unions from Paris and New York. Until World War I the other unions were usually too small to maintain a viable insurance fund.Footnote 49 So it was that the Alliance declaration ensured an especially smooth transfer of benefit entitlements between Amsterdam and Antwerp. In 1909, about 70 per cent of all transfers went between those two cities (see Table 4).

Table 4 Number of diamond workers moving to Antwerp and Amsterdam from other cities, and vice versa, in October, November, and December 1909.

Source: Wereldverbond van Diamantbewerkers, “Driemaandelijks rapport van het bestuur aan de aangeslotene centra, over de maanden oktober, november, december 1909”, UADW archive, IISG, fo. 1909.

That smooth transfer of benefit entitlements between Amsterdam and Antwerp was facilitated by the close and long-standing connections between the diamond working communities of the two cities and by the manner in which the unemployment insurance schemes were organized. Since in both cities union membership automatically implied membership of the union's unemployment insurance fund, presenting one's union membership booklet to the board of the insurance fund in the new country of residence was enough to prove that one was “in good standing” and had been a member long enough to be entitled to benefit in case of unemployment.Footnote 50 Hence between 1910 and 1914 on average 270 workers per year, most of them Belgian, used the agreement route to preserve their benefit entitlements when moving to Amsterdam (see Figure 4; details for the other diamond centres after 1910 are not available).

Figure 4 Foreign diamond workers who moved to the Netherlands to work in the Dutch diamond industry and became union unemployment insurance members, 1910–1940.

Sources: 1910–1915: ANDB, Jaarverslag; 1923–1940: RWA, Verslag.

After World War I the unions in the English and German diamond centres and those in the French and Swiss Jura Mountains established their own compulsory unemployment insurance schemes for their members, insuring virtually all Alliance members, amounting to about 95 per cent of all diamond workers in the Western world, against the financial risk of job loss.Footnote 51 In 1920, the success of the de facto collective transnational unemployment insurance encouraged the Alliance to seek the cooperation of the Diamond Syndicate in London, the world cartel of diamond traders, to fulfil a decades’ old wish: the establishment of an official international unemployment insurance scheme, financed by a worldwide levy on the sale of all rough diamonds. However, the Alliance's proposal was rejected by the Syndicate's board.Footnote 52

That attempt by the Alliance to establish what would arguably have been the first formal transnational unemployment insurance scheme in history also signified the beginning of the end of the transnational exchange of unemployment benefit rights in the sector. One cause was the introduction of compulsory unemployment insurance in the UK in 1920 and in Germany in 1927, which did not allow the exchange of benefit entitlements without an agreement between national governments (more on this subject in the next section). Another cause of problems was the economic crisis of the 1930s. That crisis caused the French and Swiss diamond industries virtually to grind to a halt and terminated all contacts between the European and American diamond unions; indeed, only organized diamond workers from Belgium and the Netherlands still used the Alliance agreement to travel between their two countries without loss of benefit entitlements.Footnote 53 Yet in the course of the 1930s the number of diamond workers using the agreements route to move to the Netherlands dropped well below fifty per year (see Figure 4).

The final blow to the exchange of benefit entitlements in the diamond industry came during World War II, when thousands of Dutch Jewish diamond workers were sent to concentration camps by the German occupying forces, never to return, while many of their Belgian counterparts met the same fate if they were not lucky enough to escape to the UK, the USA, the future Israel, or South Africa. Meanwhile, both in the Netherlands and Belgium the Germans plundered and liquidated the diamond union insurance funds.Footnote 54 The Dutch diamond industry would never really recover from that blow, while in Belgium the surviving diamond community did succeed in rebuilding the industry, gradually turning Antwerp into the undisputed diamond centre of the world.Footnote 55 Just after the war, the Universal Alliance of Diamond Workers was re-established, now joined by unions from the new diamond-working centres in Israel and South Africa, where many diamond workers from western Europe had fled during the war. In the late 1940s the Alliance also revived its plan for an international unemployment insurance scheme financed by a worldwide rough diamond levy. As in the early 1920s, the plan was blocked by the diamond traders’ cartel in London.Footnote 56

Metallurgical industry

In the metallurgical industry, too, transnational agreements about the mutual recognition of benefit entitlements had their roots in the industry's international labour union, the International Metalworkers’ Federation (IMF, founded in 1893), which allied national unions from most of continental Europe, Scandinavia, the UK, and the USA, ultimately representing almost 900,000 metal workers by 1910.Footnote 57 At the IMF's fifth congress in 1907 full “reciprocity” between its national members was decided, providing for free admittance of each other's migrant members, who would thus retain all their benefit entitlements.Footnote 58

Yet while for some continental European IMF members the declaration seems to have been only the formalization of established practice, in the following years it remained largely a dead letter for British and American unions.Footnote 59 According to a Dutch union administrator, despite the IMF declaration, American unions continued to treat foreign workers – even members of IMF unions – “as non-members, sometimes even worse”, an attitude he attributed largely to the mass migration of labour from Europe to the USA at the time. He explained the reluctance of most British unions to admit foreign IMF members to full membership by their “terrible fragmentation […], bulky books of by-laws, and their melancholic, half-rusted association machinery”, whereas British union representatives themselves felt that the exchange of entitlements contravened “old English traditions”.Footnote 60

In the following years it was the resistance to reciprocity of the British unions particularly which prevented the IMF from materializing the promises of its declaration, until 1911 when the National Insurance Act was put into law in the UK. That act included in its provisions unemployment insurance in metal sectors such as shipbuilding, iron foundries, and the manufacture of motor vehicles; and consequently it blocked the exchange of benefit entitlements with many British union funds.Footnote 61 Therefore, at the Berlin congress of 1913, all IMF member unions accepted reciprocity concerning membership, but not concerning benefit entitlements, which was left for individual members to arrange in bilateral agreements.Footnote 62 However, the swift outbreak of World War I prevented the associated national unions from signing such agreements.

At first, the 1907 IMF declaration was largely without consequence for the ANMB (Algemeene Nederlandsche Metaalbewerkersbond, founded in 1886), the General Dutch Metalworkers’ Federation which was the Dutch representative in the IMF, because in the first few years following the declaration the ANMB had not set up any real unemployment insurance. In times of economic crisis unemployed members were supported on an ad hoc basis from the ANMB's contingency fund, until in 1912 the fund was split into a strike fund and unemployment insurance fund, both of which were compulsory for all ANMB members.Footnote 63 From that year on the ANMB signed agreements on the exchange of benefit entitlements with “several metalworkers’ unions aligned with the IMF”, although exactly which ones is unknown.

However, until the 1920s that seems to have been of limited relevance because, according to the ANMB board, foreign workers used the agreements route only if the economy in their home country was in depression while the Dutch economy was blooming, and that had not occurred until then. Moreover, foreign workers were accepted as ANMB fund members only after they had found a job in the Netherlands, a regulation which according to the board generally resulted in only “good craftsmen [who] rarely have recourse to the unemployment fund” joining the fund. All in all, the board considered the agreements advantageous to its own fund, since they encouraged Dutch members to search for positions abroad at times of high unemployment, which relieved the ANMB fund.Footnote 64

When in 1917–1918 the ANMB unemployment fund's by-laws had to be approved by the Dutch Minister of Labour in order to qualify for national government subsidies, the number of agreements between the ANMB and foreign funds seems to have been limited by the ANMB board. In 1922 the ANMB still had agreements with metal workers’ unions from Hungary, Belgium, Austria, and Germany; in practice, only the agreement with the German Metalworkers’ Federation (Deutscher Metallarbeiterverband) seems to have been of relevance. In 1929 about 90 per cent of all foreign workers using the agreements route to join the ANMB's unemployment insurance fund came from Germany. The nationalities of foreign workers in earlier years are unknown. In 1929, too, the total number of incoming foreign metal workers using the route peaked at more than 400, almost 5 times the annual average of the previous years (see Figure 5). After 1930 the number of incoming German workers decreased rapidly to zero, but that was not a result of deliberate action by the ANMB nor of action by the Dutch government to restrict membership, since the ANMB's by-laws and the Dutch government's regulations concerning foreign membership remained unchanged during the 1930s.Footnote 65 As will be shown later, in the course of the 1930s new government policies were introduced in Germany to block the exchange of benefit entitlements between the ANMB and its German counterpart.

Figure 5 New members in Dutch labour union unemployment funds: construction, diamond, metallurgical, and textile industries, and other sectors (n), 1923–1940 Source: RWA, Verslag, 1913–1940.

Textile industry

Compared to the two branches of industry analysed above, the exchange of benefit entitlements in the textile industry was even more limited. Whereas in the other two branches on average more than 100 foreign workers annually used the agreement route in the 1920s, in the same period only about half the number of textile workers did so. Yet the branch is of relevance here since it was the only one in which not only the Social Democratic union but also the Roman Catholic union actively used the agreement option, probably for two connected reasons.

First, Dutch textile factories tended to be in Roman Catholic areas – Twente in the east and north Brabant in the south of the country – while Münsterland across the German border was largely Roman Catholic and Belgium homogenously so. Second, especially in Twente, where union density in the interwar years was relatively high at 45–60 per cent,Footnote 66 the Dutch Roman Catholic Textile Workers’ Union (Nederlandsche Roomsch-Katholieke Textielarbeidersbond “St Lambertus”) was large enough to be a serious competitor to the Social Democratic General Dutch Textile Workers’ Union (Algemeene Nederlandsche Bond van Textielarbeiders “De Eendracht”). In the 1910s and 1920s the rivalry between St Lambertus and De Eendracht resulted in serious competition for members and bitter confrontations when there were strikes or lockouts.Footnote 67 Offering members the chance to work abroad without loss of unemployment benefit entitlements seems to have been part of the competition.

Figure 6 Banner of the Dutch union of textile workers “De Eendracht”, section Neede. Industriebond FNV, Collection IISH

In the textile industry, too, arrangements for the exchange of benefit entitlements preceded national government intervention in union unemployment insurances in the Netherlands. In 1910 De Eendracht signed an agreement with the like-minded German Textile Workers’ Union (Deutscher Textilarbeiter-Verband), whereby both unions promised to accept the entitlements of each other's members without reservation.Footnote 68 When in 1914–1918 the first national subsidy schemes were established in the Netherlands and the RWA further regularized the organization of the subsidized funds, De Eendracht – after encouragement by the Minister of Labour – requested a continuation of its cooperation with its German counterpart, which was granted after the RWA's approval of the agreement document.Footnote 69 In the next year St Lambertus signed its own agreements with the German Central Association of Christian Textile Workers (Zentralverband Christlicher Textilarbeiter Deutschlands) and the Belgian Central Alliance of Christian Textile Workers (Centraal Verbond der Christene Textielbewerkers van België).Footnote 70

A notable feature of St Lambertus's agreements with the Belgian and German unions was that they covered cross-border workers too. St Lambertus and the Belgian Centraal Verbond agreed to accept unreservedly each other's members living in one country while working in the other. However, evidently in an attempt to tackle the problem of “moral hazard” (was a benefit claimant who used to work across the border truly involuntarily unemployed?), the union fund boards decided to meet regularly “to exchange all relevant information”.Footnote 71 St Lambertus signed a rather more peculiar agreement with the German Zentralverband. The two unions agreed that if any of their members decided to accept a job across the border they could belong to each other's fund without loss of benefit entitlements, but it was also agreed that St Lambertus would reimburse all unemployment insurance benefit costs to the Zentralverband if a Dutch member became unemployed, but not vice versa.Footnote 72

It is unclear why St Lambertus's agreements with the Belgian and German unions concerning cross-border workers, which clearly contravened the 1918 RWA ban and which were denied in other cases, were approved by the Minister of Labour. The minister who actually approved the agreements, the Roman Catholic P.J.M. Aalberse (1918–1925), who in the past had been closely connected to the Roman Catholic labour union movement and had been an MP for the town of Almelo in Twente,Footnote 73 might have been trying to help St Lambertus in its rivalry with De Eendracht. That hypothesis is backed up by another special regulation in the agreement between St Lambertus and the German Zentralverband, which stated that the membership fee minus the compulsory insurance contribution paid by a St Lambertus member working in Germany would be transferred to the German union, but again not the other way around. Cross-border workers from Twente could therefore still be counted as St Lambertus members and did not need to join the Zentralverband, which would otherwise have been the most logical option.

Until the early 1930s the agreement with the Zentralverband facilitated dozens of German union members annually accepting jobs in Dutch textiles without loss of benefit entitlements. The agreement with the Belgian Centraal Verbond largely remained redundant, since only a few sporadic Belgian individuals used it to keep their benefit rights while working in the Dutch textile industry (see Table 2). In the mid-1920s the board of St Lambertus signed agreements with unions in Austria, Czechoslovakia, France, and Switzerland, but they too seem to have been ineffective, for from 1929–1940 not a single worker used the agreements to work in the Dutch textile industry.Footnote 74 The agreements between the Dutch, German, and Belgian textile unions remained unchanged throughout the entire interwar period,Footnote 75 but their relevance diminished substantially after 1931 (see Figure 5). While at a peak in 1929 about ninety German textile workers used the agreements, half of them through the Social Democratic and half through the Roman Catholic union, there were none in 1934–1940. As in the case of the metallurgical industry, new German government policies were at the root of the development (see the next section).

The Exclusion of Foreign Workers From Dutch Unemployment Insurance Funds

In all three cases analysed in the previous section, the annual number of foreign workers using the agreements route to go to the Netherlands without loss of benefit entitlements dropped substantially after 1930 (see Figure 5), largely reflecting a general trend. From 1923–1930 an average of 560 foreign workers signed up annually for fund membership through the agreements route, but after 1930 the number quickly dropped below 100, never to recover to the figure seen in the 1920s (see Figure 2).

Moreover, in contrast, in subsequent years the number of new foreign members would cease to follow the trend in new Dutch fund members. In the first two years of the crisis the growth in the numbers of new Dutch members accelerated, the number of new foreign members already began to drop before unemployment really started to rise substantially (but with the exception of the textile industry, see Figures 2 and 4; for an explanation see below). Meanwhile, in the 1930s the composition of the new foreign fund membership underwent substantial changes. Before 1930 about two-thirds of new foreign members came from Germany, one-fifth from Belgium, and the rest from a wide variety of countries, but throughout the 1930s the number of new German fund members dropped to zero, while most of the few dozen foreign workers who still utilized the agreements route were Belgian diamond workers.Footnote 76

What had happened? The most obvious explanation for the sudden drop in foreign fund membership after 1930 is the economic crisis. We might expect the steep rise in unemployment to have curbed the flow of foreign workers going to the Netherlands and to have limited the number of foreign workers in employment (unemployed workers were not usually allowed to become fund members). The problem with that explanation is that the crisis itself initially did not result in a drop in the number of foreign workers moving to the Netherlands – on the contrary, in the first few years of the economic crisis the number of foreign workers there increased substantially, from about 86,000 in 1930 to 110,000 four years later, probably because during those years economic circumstances were deteriorating more rapidly outside than inside the Netherlands – especially true for Germany.Footnote 77 As Figure 2 shows, though, while in the years after the beginning of the economic crisis the number of incoming foreign workers increased, the number of new foreign union fund members began to drop substantially. However, in an indirect way the economic tide had a predominantly negative effect on the number of new foreign fund members, as a result of the actions of the Dutch and foreign governments.

Until the early 1930s there had been hardly any effective impediments to foreign workers wishing to go to the Netherlands to find a job, but that changed. In reaction to legislation abroad established in the 1930s and in some cases earlier, and after growing pressure in the Dutch Parliament from both the political left and right, in 1934 the Dutch government enacted the Foreign Labour Act (Vreemdelingenarbeidswet) prohibiting non-Dutch nationals from working in the Netherlands without a work permit. However, the act did not apply if there was a reciprocal agreement between the Dutch government and a foreign one whereby each authority promised not to hinder the labour migration of each other's citizens. Although in the 1930s negotiations were initiated with various countries, the Dutch government managed to reach agreements only with Belgium, Luxembourg, and Switzerland. Most far-reaching was the failure to come to a serious agreement with Germany, which until the early 1930s had been the main supplier of foreign labour. In 1936 both countries agreed to accept only a limited number of migrant workers. As a consequence of the introduction of the Foreign Labour Act, less than two years after its promulgation the total number of legal foreign workers in the Netherlands had dropped well below what it had been before the economic crisis began.Footnote 78

The introduction of the Foreign Labour Act might therefore explain the substantial drop in new foreign membership of Dutch union unemployment insurance funds from 1934 onwards, but it does not account for the earlier sharp drop between 1929 and 1934. An explanation for developments before 1934 – and perhaps subsequently – should be sought in the specific characters of the unemployment insurance systems abroad as much as that in the Netherlands. As long as systems in the union funds’ home countries had been more or less comparable, reaching and keeping to agreements was not especially difficult. Unemployment insurance funds in most European countries were administered by labour unions until the early 1920s, when government intervention in the unemployment provision system was still uncommon. In the course of the 1920s and 1930s, however, government interference in unemployment insurance increased in most of those European countries that had union unemployment insurance funds with pre-existing agreements with Dutch funds.

In those countries the insurance system was changed substantially either by the introduction of or alterations to national subsidy schemes, or through the replacement of voluntary systems by compulsory ones.Footnote 79 As has been shown in the previous section, union funds in the metallurgical industry were among the first to be affected by that development. When in 1911 the British government introduced compulsory national unemployment insurance for a number of sectors, including many metallurgical trades, agreements on the exchange of benefit entitlements between British and Dutch or other national metallurgical unions became impossible. With compulsory unemployment insurance in Britain being extended in 1920 to virtually all manual workers, the exchange of benefit entitlements between British and other national diamond union funds too was blocked.Footnote 80

Yet, from a Dutch perspective, most relevant were developments in Germany, in the 1920s the main “provider” of new foreign members for labour union funds. In 1927 a compulsory unemployment insurance scheme was introduced in Germany to cover the large majority of the dependent labour force. The scheme was administered by regional and local agencies, governed by boards composed of employers’ representatives, labour unions’ representatives, and by regional and local authorities under the supervision of a central state agency. The new act covered foreign workers living and working in Germany but excluded foreign cross-border workers, with the exception of those from countries that, in the opinion of the German Minister of Labour, had a “similar welfare system”. Unlike the Austrian and Polish unemployment insurance systems, the Dutch system was not deemed “similar” to the German scheme, so from 1927 all Dutch employees working in Germany but living in the Netherlands had no unemployment insurance.Footnote 81 In the years following the introduction of the new German scheme, the Dutch Ministry of Labour carried on negotiations with the German government to find a solution for Dutch cross-border workers, but no agreement was reached. The only result was that those workers were no longer obliged to pay premiums in Germany for unemployment benefits they were not entitled to anyway.Footnote 82

By excluding Dutch cross-border workers the newly introduced German insurance struck a blow to the exchange of benefit entitlements between Dutch and German labour unions, although it did not mean the end of it – at least not immediately. Though in principle the German scheme was administered by tripartite regional and local agencies under the supervision of a central state authority, under certain conditions workers could be exempted from the compulsory insurance if they were already insured with a union or employer's insurance fund at the time the new scheme was introduced.Footnote 83 However, not all German unions chose to continue their unemployment insurance. For example the Zentralverband Christlicher Textilarbeiter Deutschlands, which since 1918 had had an active exchange relationship with the Dutch textile union St Lambertus (see the previous section), discontinued its unemployment insurance, though for some years St Lambertus continued to recognize the benefit entitlements of Zentralverband members.Footnote 84 On the other hand the German Deutscher Metallarbeiterverband, which had signed an agreement with the Dutch ANMB (see the previous section), continued its work, which included insuring ANMB members working and living in Germany.Footnote 85 Nevertheless, after the rise to power of the Nazi party in 1933 the administration of unemployment insurance in Germany was rigorously centralized and all regional, local, and other agencies abolished, signalling the end of labour union involvement in the administration of insurance schemes. In any case, a few months later all free unions were outlawed altogether, and so the exchange of benefit entitlements between German and foreign unions came to an end.Footnote 86

After 1933, as a result of the termination of the exchange of benefit entitlements between Dutch and German unions, Belgium became de facto the only “provider” of new foreign members for Dutch union funds, apart from some isolated individuals from Czechoslovakia, France, and Switzerland – it was no coincidence that each of those countries had voluntary unemployment insurance systems run by labour unions – and from 1934–1940 all the foreign workers who came to the Netherlands using the agreement route were Belgians. Meanwhile the total number of foreign workers dropped substantially, most probably due to the introduction of the Foreign Labour Act in 1934. Hence, by 1940 the constant stream of foreign workers using the agreements route, which at its 1929 peak amounted to over 1,000 individuals, had dried up almost completely. In that year only 39 foreigners, more than one-half of them Belgian diamond workers, were granted fund membership without losing their benefit entitlements.Footnote 87

Concluding Remarks

The pre-war history of subsidized union unemployment insurance funds in the Netherlands presented in this article illustrates that transnationalism in social welfare in the period did not necessarily involve transnational policy transfer and policy learning alone, but also the building of transnational welfare schemes. In the case of union unemployment insurance, in the early twentieth century transnational relations were established which facilitated the transfer of benefit entitlements across national borders, largely without national or local government interference. In this article, the transnational exchange of unemployment benefit entitlements is described and analysed from the Dutch perspective and with particular focus on three sectors in which the exchange of benefit entitlements had practical relevance: the diamond, metallurgical, and textile industries. In those sectors the agreements that enabled the exchange of benefit entitlements came about and functioned in various ways. In the diamond industry a collective agreement signed by all members of the trade's international union lay at the heart of the exchange, in the textile industry it was bilateral agreements between unions, and in the metallurgical industry it was a combination of the two.

For the Dutch funds solidarity with foreign fellow craftsmen seems to have been the main reason for signing the agreements, but there were also more practical considerations such as international cartel formation against employers (in the diamond industry), the relief of one's own fund (in the metallurgical industry), and competition with other national labour unions (in the textile industry). In all three sectors the exchange relationships seem to have functioned on the basis of only a few regulations, and foreign members only had to prove to the Dutch union board that they had been union members in their home country for long enough to be eligible for benefit in the event they became unemployed. Obviously, the exchange relationships did not need extensive regulations and a supervisory apparatus to ensure good behaviour, for after all, as Marco van Leeuwen argues, the social control and trust that characterized social relations within the early labour unions was the best warranty against moral hazard and fraud.Footnote 88 Interestingly, the trust relations also encompassed befriended unions and their members in other countries.

It is hard to imagine how the de facto transnational insurance arrangements analysed in this article could have functioned if national governments, instead of labour unions, had been in charge of unemployment insurance. In a time of limited communication technologies, civil servants would have had to discuss the eligibility of dozens of workers for a type of social insurance that was considered at the time as one of the most complicated and risky ones, in cooperation with anonymous colleagues in distant countries. It should therefore come as no surprise that when unemployment insurance actually became the competence of national bureaucracies in the 1920s and 1930s in countries like Germany and the UK, foreign workers were excluded from eligibility – either directly and explicitly in the insurance regulations or as a result of the incompatibility of national systems. Exchange of benefit entitlements now required the conclusion of reciprocity agreements between states, which in the 1930s especially had to deal with populations distressed by unemployment and increasingly mistrustful of foreign workers competing for the same scarce jobs.

Yet, whereas in the 1920s and 1930s foreign states terminated transnational insurance relations, from the same period there is nothing at all to suggest that the Dutch government used its growing grip on union unemployment insurance funds to prevent them from signing transnational agreements or from terminating existing ones. On the contrary, in some cases the Minister of Labour even encouraged funds to seek transnational cooperation. One reason for the positive – or at least indifferent – official Dutch attitude to transnational cooperation might have been the fact that (at least in 1923–1926) many more Dutch than foreign workers were using the agreements, making them financially attractive to the Dutch government.Footnote 89 Another reason could well have been the preference for “laissez faire” and “private initiative” over state intervention in social security, which until deep into the 1930s was shared as enthusiastically by the civil servants of the Ministry of Labour as by all the major Dutch political parties – apart from the Social Democrats.Footnote 90

After World War II the links between the Dutch and foreign unemployment insurance schemes were finally severed, and since the Dutch union funds had been comprehensively raided by the German occupying forces during the war, unemployment insurance had to be rebuilt from scratch.Footnote 91 Under new national and compulsory insurance rules introduced in 1949 foreigners working and living in the Netherlands were automatically insured against the risk of unemployment, but benefit entitlements could be transferred only to or from countries that had signed special agreements with the Dutch government.Footnote 92 The transfer of unemployment benefit entitlements was thus no longer facilitated by transnational agreements between independent union funds but by international treaties between states.