To most observers, Rio de Janeiro’s labour movement after 1906 appeared clearly divided into two antagonistic factions: “revolutionary syndicalism” or followers of “direct action”, on the one hand, and “reformist” trade unions on the other. This division persisted at least up to the 1920s, when a third competing force, the Communist Party, entered the dispute. However, like in many other countries, these two currents continued to be major referents in the subsequent political disputes within the labour movement. Until today, these labels are among the best known in the history of labour movements: They are firmly established, even iconic attributions, apparently valid all around the world with a stable meaning. Furthermore, they have been perpetuated by historians, who use them to make sense of different actors and currents in the history of labour. Of course, to a high degree these labels refer to differences that were real (both in the sense of stemming from realities and of creating these realities through their discursive power), and such differences are most commonly defined along a spectrum of certain programmatic and strategic orientations. Yet, as has repeatedly been pointed out by both activists and academics, they are also deeply problematic: their meaning shifts over time and, within one period, is not the same in different locations; their boundaries are not clear cut, sometimes even fluid, even within or in relation to the same organizational and individual actors (especially over the course of a lifespan). In addition, this division, to the degree that it was real, was rendered in different terms. In the case of Rio’s labour movement, for instance, an observer in 1913 spoke of a dispute between “legalists”, i.e. all “movements submitted to political discipline – parliamentarism – organized in a great political party” and the “revolutionary column, which knows no political discipline and uses direct action as its sole means”.Footnote 1

The unclear boundaries between the “reformist” and “revolutionary syndicalist” spheres are further complicated by the fact that all labels involved are controversial in their own right, denoting more a spectrum of positions and practices than a stable phenomenon. Especially the interrelation (or not) between “syndicalism” sans phrase, “revolutionary syndicalism”, and “anarchism” haven been debated vigorously among scholars: Sometimes an identity is presupposed (“revolutionary syndicalism” being a specifically anarchist form of unionism), sometimes a much looser and often discontinuous affinity is envisioned, sometimes an independence of each current is insisted upon.Footnote 2 As this article will make clear, the case of Rio de Janeiro gives credence to those positions that see “anarchism” and “revolutionary syndicalism” as often interrelated, though not at all moments and under all circumstances.

The aim of this article is thus to explore how the boundaries between “reformist” and “revolutionary syndicalist” ideological currents and union practices were drawn in the case of Rio de Janeiro, and the way in which these were, at the same time, blurred from the beginning, becoming even more fluid over time, especially in the context of the long strike waves between 1917 and 1919.Footnote 3 The particularities of Rio de Janeiro (the capital of Brazil during this period) are highlighted by pointing to some differences with international trends and by comparison to other locations and regions in Brazil, especially São Paulo, where a different constellation of forces led to a different outcome. The argument is based on the research conducted in Brazil on the trajectories of revolutionary syndicalism and anarchism,Footnote 4 as well as on recent international debates, which both stress their transnational connectedness and their remarkable changeability according to different contexts and circumstances.Footnote 5

Who Were the Working Classes in Rio de Janeiro?

According to the 1920 Census of the Federal District, which encompassed the city of Rio de Janeiro and its environs, the city had 1,157,873 inhabitants, representing an increase of forty-three per cent over the 811,443 found in the previous Census of 1906.Footnote 6 Men formed 51.8 per cent of the population in 1920, slightly outnumbering women (48.2 per cent).Footnote 7 The preponderance of men in the population was attributed to mostly male immigration. Foreigners represented 20.6 per cent of the population (of which only thirty-five per cent were women), a proportion that had been rapidly decreasing since the beginning of the century.Footnote 8

Foreigners represented an important part of Rio de Janeiro’s population and of its workforce but, unlike in southern Brazil, Rio’s immigrant population was composed primarily of adult males. Hence, the formation of relatively closed immigrant communities was less frequent and integration easier (“integration” here meaning a more regular contact between the immigrant communities as well as between these and the wider Brazilian society). Another aspect of Rio’s particular demographics, which, in comparison with other Brazilian cities, smoothed over differences within the capital, was the fact that the Portuguese were by far the largest immigrant group (followed by Italians and Spanish), so language was no barrier between them and Brazilian-born workers. Despite their relatively limited participation in the total workforce, foreign-born workers formed the majority in certain trades, industries, and even whole sectors, such as wood processing (slightly over 50 per cent), the food industry (52 per cent), land and (curiously) air transportation (51 per cent) and commerce (57 per cent).Footnote 9 Women represented about 27 per cent of the industrial workforce, while they formed a clear majority of workers in the garment industry (62 per cent) and, as elsewhere, in domestic service (82 per cent). In comparison, the share of women among all industrial workers was slightly higher in the city of São Paulo (29 per cent), but there they made up 58 per cent of the workers in the textile industry (production of yarn and cloth), while in Rio women comprised no more than 39 per cent of this sector, for reasons that are not entirely clear.

Until the 1920s, Rio de Janeiro was the country’s principal industrial city. Of the ten most important cotton mills of Brazil in 1915, six were installed in the Federal District,Footnote 10 and textile mills were by far the most mechanized and employed one of the largest workforces. But other branches of industry and services exceeded the workforce employed in the production of yarn and cloth, such as construction, transportation, the garment industry, wood processing, and even metal works. Industries were, in general, predominated by small-size establishments with a mostly low level of mechanization. For instance, one post-World War I observer commented on the shoe industry:

The manufacture of shoes has been greatly stimulated by the war, although the industry has been well established for some time. There are over 4,000 shoe factories in Brazil, including the home industries, but there are only 116 establishments which employ more than twelve people, and only sixty-one have between six and twelve employees. The modern factory system, the piecework system, and the home industry are all competitors.Footnote 11

Of the 116 plants mentioned above, fifty-five were located in the Federal District. Although the shoe industry is an extreme case, this excerpt illustrates vividly the coexistence of different “stages” of production in Brazilian industry. Even the textile industry, in which, according to the aforementioned report, “many of the plants are equipped with the most modern machinery and are run by electricity, comparing favourably with the great New England mills”,Footnote 12 had a broad range of technological levels. In the Federal District, alongside the cotton mills employing thousands of workers, a wool manufacturing facility had only thirty employees.Footnote 13 The contrast was even more accentuated in the city of São Paulo, with numerous manufacturing facilities not having more than two to five workers.Footnote 14

The censuses show a significant number of adults (twenty-two per cent of the total population in 1920) classified under categories such as “ill-defined professions” or “undeclared professions”, which certainly encompassed not only the “dangerous classes” of vagrants, beggars, criminals, sex workers, etc., but also the casual labour force that was essential to the operation of the city’s port and various other activities.

During the 1980s, scholarly works, especially those influenced by sociology, typically tried to establish a correlation between nationality, profession, and ideological choices. In short, this scholarship implied that immigrant industrial workers were more likely to turn to direct action,Footnote 15 while Brazilian port or transportation workers would choose reformism. Workers employed in strategic sectors of a commodity-export economy would undeniably have more leverage to negotiate and to have their demands met. The exact opposite would happen to industrial workers who produced mainly consumer goods.Footnote 16 Nevertheless, there is substantial evidence that supplies counter-examples to this kind of premise, thus any automatic correlation between structural circumstances and ideological choices impedes our understanding of the multiple and complex factors, many of them conjunctural, that lead people to take a particular political stand.

The 1906 Labour Congress

The First Brazilian Workers Congress, which met in Rio de Janeiro from 15 to 20 April 1906, only became possible after a long organizing process in which different groups proposing the congress finally managed to agree. Despite all the effort and the twenty-eight delegates present (sixteen of which were from the Federal District, that is, the city of Rio de Janeiro), in fact they represented only five states. Nonetheless, this congress attempted to bring together different currents – in itself a remarkable fact in view of the already clearly established separation between anarchism (and its numerous tendencies) and socialists in many European countries at the time. The congress confronted a series of classical issues of political and strategical orientation (formation of a political party, participation in elections, relations between trade unions and political organizations, forms of struggle, etc.), and it established the defining characteristics of the labour movement for the next two decades.

Edgard Leuenroth (1881–1968), one of the main leaders of São Paulo’s anarchists, cunningly eliminated any discussion about the possible creation of a working-class political party, a point scheduled for debate by the congress, by proposing a resolution establishing that “the congress was composed of working-class associations organized on economic grounds, and it was not intended to discuss political opinions and actions of the members of those associations”.Footnote 17 Thus, the approval of Leuenroth’s resolution by a majority of delegates rendered any further discussion of political action meaningless. The congress decided to found the Confederação Operária Brasileira (COB; Brazilian Workers Confederation) as an umbrella organization, inspired by the French General Confederation of Labour (CGT) and thus of clearly syndicalist orientation. Years later, a report by the COB presented to the 1913 workers’ congress described what happened in 1906 in a way that is worth quoting at length as it makes clear how the identifications of “reformist” and “revolutionary syndicalist” were clearly becoming discernible, although not necessarily with these labels:

If it were not for the combative temperament of the delegates representing São Paulo’s workers, united with the representatives of Rio de Janeiro, already seasoned by previous fights, the 1906 Congress would have been useless for the working class of Brazil, since its main promoters were committed to extract from that magnificent clash of ideas a strong political party to serve the interests of the bourgeoisie.

[…] The struggle sustained in that memorable encounter of two currents of action, until then unknown, was one of the most exciting we have witnessed. On the one hand – the majority – highly organized in their efforts to make a compromised set of ideas prevail, a real denial of common interests; on the other hand – the minority – a phalanx of brave companions who are propagators of new ideals, tired of promises, full of ardour, bearing the torch of solidarity, fighting against prejudice, snatching the naïve worker from the darkness of ignorance, illuminating our camp with the light of their knowledge on the question that concerns us and that will inevitably lead us to the final destination of our aspirations, which is the abolition of this iniquitous regime, this dammed institution.

Reason, thus, has won against ignorance and wickedness.Footnote 18

It is remarkable how this quote presents those who, after all, managed to convince the majority to vote for this resolution as a struggling and somewhat heroic minority, and those defeated as an oppressive majority. Furthermore, it is striking how the partisans of direct action here consider their political project as one of “illumination” and education.

Whatever the numeric correlation of forces at the beginning of the congress (when it seemed that the reformist side had a majority), in its main resolutions the principles of revolutionary syndicalism held sway, especially in relation to two issues: the forms of action to be adopted and the way trade unions should be structured. Under the general principle of direct action, the resolutions prescribed that workers themselves should take action against employers without help from outsiders (such as politicians, government officials, lawyers), by means such as boycotts, sabotage, and strikes. For its part, the trade union organization had to be autonomous and as unbureaucratic as possible, with no paid officials, directed by an executive committee with no hierarchical distinction between its members, and dedicated exclusively to “economic” struggle, that is, to improving wages and working conditions. Activities such as cooperatives and those related to mutual aid, which where common in most Brazilian working-class associations by that period, were considered undesirable and should be avoided by unions. A number of trade unions based on these principles were founded in the aftermath of the congress, but very few survived the industrial crisis that bore a powerful impact on employment and working-class organization between 1908 and 1911.

Congenial Non-identity: Revolutionary Syndicalism and Anarchism

Revolutionary syndicalism was an international current in the labour movement, although it could assume quite different characteristics in the various national contexts in which it was present. In its original French version, revolutionary syndicalism was formed by labour activists, many of whom were former anarchists or socialists, into a third and quite distinct ideological current.Footnote 19 In Italy, it was the offspring of the anti-parliamentary left wing of the Socialist Party. A similar process occurred in the Argentinian case, where also it emerged from socialist ranks.Footnote 20 In the USA, and to a lesser degree in Canada, it can be associated with the organization of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which had its own particularities.Footnote 21

It is doubtful whether revolutionary syndicalism ever represented a consolidated political current in Rio de Janeiro. It was, rather, an ideological reference point and a conception of how trade unions should be organized, and it was a set of ideas adopted by anarchists in the trade union movement. In this sense, Rio de Janeiro was quite different from São Paulo, where in addition to anarchists adopting revolutionary syndicalist practices, a distinct revolutionary syndicalist current emerged under the leadership of Italian socialist militants such as Alceste De Ambris.Footnote 22 Other major differences between the two cities, which may help to understand certain political choices, are that the Brazilian capital had a middle-class opposition that eventually established alliances with the working class, while nothing of the sort existed in São Paulo. Also, repression of the labour movement in São Paulo tended to be far more brutal than in Rio. Nevertheless, it is quite likely that, in Rio, a number of trade union officials were more attracted to a revolutionary syndicalist stance than to an anarchist ideology proper.

Whether or not Brazilian revolutionary syndicalism ever became a coherent political project, one thing is certain: theirs was a moderate version of its European counterpart. The resolutions passed by the First Workers Congress in 1906, which endorsed direct action and other revolutionary syndicalist conceptions, never used the word revolutionary either as an adjective or as a noun.Footnote 23 This can be attributed, at least in part, to the need for partisans of revolutionary syndicalism to convince delegates of that congress to adopt their approach to labour organizing; in other words, to the fact that the results of the congress were a compromise. Yet, despite such constellations of opportunity and necessary compromise, Brazilian revolutionary syndicalism was certainly more syndicalist than revolutionary on its own terms, precisely because it had less affinity to the ideological horizon of a larger project (“revolution”) and more to the cornerstone of syndicalism, the limitation to the “economic” struggle. This does not mean the ideas of French or Italian revolutionary-syndicalists were unfamiliar to Brazilian activists: For instance, as advertised in the COB newspaper, A Voz do Trabalhador, the writings by the following were found on sale at the federation’s offices: Émile Pouget, Victor Griffuelhes, Marc Pierrot, Aristide Briand, Enrico Leone, alongside Marx and anarchists such as Malatesta, Kropotkine, Réclus, or Grave.Footnote 24 And translated articles written by Pelloutier, Pouget, Lagardelle, Yvetot, or Gustave Hervé (or at least quotes from them), were published not only by A Voz do Trabalhador, but also other papers of the labour press.Footnote 25

Whatever the proximity of the unions of syndicalist orientation and anarchist groups, as far as the leading persons promoting revolutionary-syndicalist principles in labour unions (which included philosophical, political and religious neutrality) were concerned, these were, in most cases, outspoken anarcho-communists – in other words, followers of the international anarchist current whose most famous representatives included Kropotkin in Russia and Malatesta in Italy. In Brazil, the principal theoretical defence of anarchists’ adoption of revolutionary-syndicalist practice within unions came from the São Paulo-based, Portuguese-born journalist, Gregorio Nazianzeno de Vasconcelos (1878–1920), better known as Neno Vasco.Footnote 26 Although this position managed, until 1920, to assure a solid majority among anarchists who supported participation in the trade union movement, it had to deal with contestation both from anarcho-communists who opposed trade union action altogether and from those who, in an opposite but similarly radical stance, sustained that unions should adopt anarchism in their programmes. Both views had some currency in the state of São Paulo, less so in Rio de Janeiro.

The historiography concerning the Brazilian labour movement, especially up to the 1990s, tended to use the term “anarcho-syndicalism” to designate anarchists acting in trade unions, despite the fact that this term did not appear in Brazilian labour vocabulary before mid-1920s, and even then usually with pejorative connotations. The term only began to appear more frequently in documents produced by the Communist Party (PCB) from 1928 onwards.Footnote 27 The popularization of this designation in labour history reaches back to the writings in the post-war years of militant historians, many of whom were members or former members of the PCB.Footnote 28 The use of this term, however, is by no means a Brazilian peculiarity. Such English-speaking historians as George Woodcock use it as a synonym for “revolutionary syndicalism” when speaking of France.Footnote 29 But this designation, as more recent labour history has shown, is both imprecise and problematic:Footnote 30 If the designation is controversial for the French case, where not all revolutionary syndicalists came from anarchism, it is completely preposterous when speaking of the Italian or the Argentinian case, where they came mostly from socialist ranks. In the Brazilian case, with its considerable regional differences in almost all matters related to the labour movement, at least until the mid-twentieth century, such an approach certainly does not aid understanding of the complex relationship between anarchism and revolutionary syndicalism, nor does it illuminate the specific contours that this relationship acquires in different places, such as Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

One final aspect to be considered are the individuals – more than one anarcho-communist changed position concerning trade union activity according to the shifting historical circumstances. José Elias da Silva, for instance, one of the future founders of the PCB, in 1913 served as the Secretary General of the Federação Operária do Rio de Janeiro – FORJ (Rio de Janeiro’s Workers Federation), the city’s most important revolutionary syndicalist organization. Three years later, at a moment when labour associations were experiencing a major crisis, he published, together with two other disillusioned anarchists, a pamphlet that harshly criticized the participation of anarchists in trade unions.Footnote 31 As the labour movement regained force in 1917, Silva returned to the syndicalist ranks. In other words, for many, revolutionary syndicalism was not a matter of principle, but rather a form of action to be adopted under favourable circumstances.

The Currency of Reformism and the Absence of a Socialist Party

Reformists in the labour movement were a similarly heterogeneous sphere of different positions, ranging from trade unionists seeking concrete improvements for their specific crafts or industries to socialists trying to establish links between unions and working-class parties; a number of other ideological orientations inhabited the wide space between these two extremes. Craft or class, political activism or neutrality, cooperation resp. negotiation or class confrontation were some of the issues that divided the heterogeneous reformist camp. In addition to socialism, other tendencies were present, one of the more significant being positivism. Positivism (in a local and, again, heterogeneous adoption of the French version) had been a guiding ideology for Brazil’s First Republic (1889–1930), informing various sectors of the state, the military and middle-class professionals, while also having some currency among wider layers of the population. One of the tenets of this positivism was to acknowledge and address the “social question”. Its adherents within the labour movement proposed that workers participate in elections and present their own candidates.Footnote 32

Unlike other South American cases, including Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile, no enduring, unified, and nationwide socialist party was established in Brazil before the 1940s, something that should be seen as one the main determinants of the country’s political history and which poses a major challenge for labour historians to explain.Footnote 33 One must recall that all Brazilian politics during the First Republic (1889–1930) was based on single states, thus political parties had a state and not a national organization (the first important exception would be the 1922 Communist Party). Even the few attempts to create ruling-class national parties failed. Furthermore, Brazilian socialists never had any solid connection with the Socialist International, among other reasons, because the many labour and socialist parties created from the 1890s to the 1930s did not last long enough for this connection to be established. All formal contact with the International was limited to two reports sent by German-speaking workers, members of São Paulo’s Allgemeiner Arbeiterverein (General Workers’ Association), in 1893 and 1896.Footnote 34 Nevertheless, the lack of organic links with the International did not mean other forms of contact with international socialism did not exist, such as correspondence, the exchange of periodicals, migrational links, occasional visits by militants, and so forth. Italo-Argentinian José Ingenieros and Portuguese social-republican Sebastião Magalhães Lima played a major role in the 1890s as correspondents of Brazilian socialist newspapers and in introducing various works and their authors to local socialists.Footnote 35 The works known to Brazilian socialists, mostly through French, Italian, and Argentinian editions, reflect an eclectic, mainly reform-oriented socialism. Authors made known to Brazilian activists in this way included Benoît Malon, Gabriel Deville, Filippo Turati, Enrico Ferri, Ferdinand Lassalle, August Bebel, or Friedrich Engels. Marx, although frequently quoted, was mainly known through the interpretations and didactic syntheses of his work then in circulation.Footnote 36

Local socialists not only mixed different authors, in a practice that was not uncommon in many parts of the world during the Second International, but also proposed a selective reading of these authors. For instance, Benoît Malon, who was one of the most popular among Brazilian socialists, was stripped of an essential aspect of his thinking, his defence of federalism. Likewise, Brazilian socialists’ selective reading of Malon disregarded his anti-Semitism (something many French socialists had also turned a blind eye to before the Dreyfus Affair).

The positivists or followers of what was known as the “Labour Cult” (Culto do Trabalho), under the leadership of Francisco Juvêncio Sadock de Sá, a mechanic who worked as a foreman at Rio de Janeiro’s Army Arsenal, were an ideological phenomenon that was specific to Rio de Janeiro (with limited presence in some other cities) and, although based on an interpretation of Auguste Comte’s writings, with no apparent links with international tendencies. Initially, during the early years of the twentieth century, Sadock de Sá and his followers held positions similar to those of other reform-oriented groups promoting working-class candidates in local and federal elections, demanding labour laws, supporting strikes (but only under certain circumstances), and making vague references to socialism.Footnote 37 By the end of the first decade of the century, with the creation in 1909 of the Círculo dos Operários da União (Federal Government’s Workers Circle), however, followers of this ideological tendency became a pressure group that primarily recruited its followers from the ranks of workers employed in state-owned firms. With their stance towards the state significantly softened, they proposed collaboration with government, “social harmony”, the adoption of an anti-strike stand, withdrawal from collective action with other workers, and a new focus on getting favourable laws passed by means of petitions and other forms of pressure on the National Congress as well as the government. It is thus not surprising that the associations that followed this tendency refused to participate in any of the working-class congresses after 1906.Footnote 38

A number of reform-oriented unions – probably the majority of them – had no particular ideological affiliation; they were “reformist” by default and aimed to obtain gains for the particular crafts and sectors they represented by whatever means they found suitable. This trend was particularly present among Rio’s dockworkers’ and stevedores’ unions, in which semi-professionalized and clientelistic leaders known as the “Colonels of the Port” (Coronéis do Porto) dominated for a long period.Footnote 39 In many respects, these unions had positions similar to those of the American Federation of Labor under Samuel Gompers, with its epitomized mix of confrontational action when necessary and negotiation whenever possible. Similarly, Rio’s port strikes were among the most violent during the period, and these unions did not hesitate to strike when necessary. At the same time, these unions and their leaders were often especially supportive of authorities and rushed to endorse government policies during World War I.Footnote 40

Regardless of their differences, the diverse reformist tendencies had much in common. Firstly, all conceived strikes were to be a last resort, used only when all other means of pressure had failed. In contrast with revolutionary syndicalism, any help to obtain their demands was welcome, so during labour conflicts they would frequently appeal to lawyers, politicians, government officials, the Chief of Police, ministers, and even the president of the Republic seeking mediation. Another distinctive quality of reformist unions was their view of working-class associations: to be strong, even during periods of crisis, they should be able to offer their associates modes of support beyond fighting for their labour demands, such as providing mutual aid and cooperatives. Furthermore, trade unions should be institutionally efficient and effective, for which hierarchical boards of directors and headquarters in the union’s own premises were required. In other words, institutional and financial stability were seen as essential for trade unions to reach their objectives.

Until the 1980s, “reformism” was completely misunderstood by Brazilian labour history. Based on their fundamental belief in liberal or orthodox Marxist presuppositions, historians tended, first, to conflate the broad and shifting spectrum of reform-oriented unions, non-confrontational currents, and socialist activism under one label and, second, to view reformists as manipulated either by the state or by employers, denying them any agency. At least in part, this view was inherited from Astrojildo Pereira, a former anarchist who later became Secretary General of the PCB and, later, one of the main exponents of militant labour history.Footnote 41 In the mid-1910s, still in his anarchist years, Pereira began to refer to reformists using the term sindicalismo amarelo (yellow unionism), which explicitly established a parallel with the French syndicalism jaune, a conservative, Catholic, and anti-socialist labour ideology sponsored by employers. The obvious differences between this French approach and the Brazilian reformists mattered little, what mattered was the political impact of such labelling. The relative success of this denunciation can be gauged by the long shadow this label was able to cast, including on historiographical assessments. Until recently, reformism, whatever terms it was described in, was either seen as negligibly small or altogether suspicious: While for some it was a phenomenon limited to Rio de Janeiro, for many others it was an early manifestation of the state-controlled unionism that existed from the 1930s onwards under the corporatist regime of Getúlio Vargas. A series of recent studies has revisited these received wisdoms, making clear that reformists had agency both during the First Republic and after, and that their role during the 1930s and under the Estado Novo (1937–1945) dictatorship was more complex than previously thought. Furthermore, these studies have also revealed that it was a much more widespread phenomenon, both numerically and regionally, that was present, in one way or another, in most of Brazil.Footnote 42

Labour Division between Two Congresses

The number of trade unions and of the workers they organized grew steadily between 1902 and 1908, in particular in the aftermath of the 1906 congress, which was accompanied by victorious strikes. Unionized workers at this time remained mostly male and belonged to the skilled trades. From 1907 onwards, the tide turned in Rio and wages, which had continuously increased since the earliest years of the century, began to decrease in some industrial sectors, while food and housing became more expensive. Government monetary and taxing policies benefitted the importation of manufactured goods, leading industries to slow down production and to fire their workers. To render the situation even worse for organized labour, in 1909 a number of important strikes were defeated. Under these circumstances, not surprisingly, many working-class societies ceased to exist or, at least, closed down temporarily.

By 1911, the labour movement began a slow recovery as old associations were reactivated and new ones created, while strikes increased once again. One year later, some of the reformist unions decided to organize their own congress, which they called the Fourth Brazilian Workers’ Congress (4ºCongresso Operário Brasileiro). The organizers of this gathering considered the 1906 Congress as the third of its sort and counted the socialist congresses of 1892 in Rio de Janeiro and of 1902 in São Paulo as the first two events.

At that time, Brazil’s president was Field Marshal Hermes da Fonseca (1910–1914), whose election has resulted from an alliance between the oligarchies of a number of states that had previously had relatively little power in national politics and the military. Hermes da Fonseca was one of the first presidential candidates to mention the existence of a social problem and, consequently, he received support from part of the labour movement. Thanks to these circumstances, the Congress managed to obtain some support from the government, such as free train tickets and the use of a government venue, the Monroe Palace in Rio, then the seat of the Brazilian Senate. The Congress was held from 7 to 15 November 1912 and was composed of seventy-four delegates (sixteen of whom were from Rio), representing thirteen different states.Footnote 43 Some of the resolutions approved did not differ greatly from the type of demands usually presented by the partisans of direct action, such as the eight-hour work day, weekly rest, indemnities for work accidents, regulation of women’s and child labour, and so forth. Yet, other proposals would immediately be met with opposition from revolutionary syndicalists, such as the approval of the creation of an umbrella organization named the Confederação Brasileira do Trabalho (Brazilian Confederation of Labour), which was simultaneously a political party and a confederation of trade unions. Following the contemporary critics of this Congress in the labour movement, especially anarchists who were excluded (with very few exceptions) from participation, the historiography has tended to view the Congress as an early expression of peleguismo. Footnote 44

It took the adherents of revolutionary syndicalism a little longer to give an appropriate response to the challenge represented by the reformists, because its main organization, the COB, founded in 1906 yet hibernating since 1909 (when a congress was supposed to take place but never actually happened), was only reorganized at the beginning of 1913. By September of this year, the confederation finally managed to hold a new congress. In comparison to the competing congress, the COB event had fewer delegates (sixty-two), but a superior number of states were represented (nineteen). At the same time, the Second Brazilian Workers’ Congress (whose very name showed their disregard for the reformist view of the legitimate lineage of congresses) had to deal with several problems: in addition to having to face a reinvigorated reformist camp, it saw an urgent need to launch campaigns to confront the growing increase in the cost of living and to oppose a new law mandating the expulsion of foreigners. As part of its mobilization against the law, the COB sent representatives to Europe to campaign against emigration.Footnote 45 Interestingly, the resolutions passed at this congress were largely similar to those approved in the one held in 1906. The main difference in 1913 was that the rhetoric of revolutionary syndicalism finally came to the fore; indeed, unlike in 1906, when the word “revolutionary” was never uttered, participants in this later gathering explicitly discussed the possibility of a “revolutionary general strike”.Footnote 46

The 1912 and the 1913 congresses where held at a moment when unions had just begun to reorganize, but instead of contributing to unity these events exacerbated division. This was a period that witnessed the brief rebirth of the labour movement, which soon after plunged into a new crisis that grew in intensity as World War I began. By mid-1915, the COB stopped the publication of its newspaper, A Voz do Trabalhador, and vanished from the scene shortly thereafter.

The Growth of Labour Protest in 1917–1919

As World War I proceeded, industrial activity regained momentum, while competition from foreign industrial goods diminished with the sharp decrease in imports. The cost of living, however, kept rising as industrialists maintained wages at a stagnant level, a combination of factors that created favourable conditions for labour protest. From 1916 onwards, Rio de Janeiro’s labour movement began to reorganize itself as old unions reopened and new ones were created. One major change during the period was the creation of local industrial unions in sectors of production that, until then, had been divided into various craft unions, such as among metal and construction workers. This change also allowed for greater participation of unskilled workers in unions, where their presence had previously been quite limited. Another change was the creation of two federations that were less based on sectors than on similar jobs and activities: one was the Brazilian Maritime Federation (Federação Marítima Brasileira – FMB), combining port and maritime workers’ unions; the other was the Vehicle Drivers’ Federation, which gathered the land transportation unions. Both of these federations were considered as reformist, although, again, this meant quite different orientations and practices in each case.Footnote 47 By 1917, labour had regained and surpassed the force it had during the period from 1912 to 1913. As workers from various sectors of the economy went on strike, in particular to demand better wages and working conditions, they initiated a prolonged cycle of struggles that lasted until 1919. This cycle had its own local backgrounds (often greatly varying between its numerous locales in Brazil); yet, it was also connected to the international wave of labour, often revolutionary unrest at the end of World War I and in the wake of the Russian Revolution. In international comparison, it is a relatively sustained series of mobilizations, lasting much longer than in many other countries. At the same time, the mobilization’s ability to shatter the whole of society remained more limited in Brazil than in other places.Footnote 48

Although general strikes took place in 1917 in Rio and in other major Brazilian cities like São Paulo and Porto Alegre, each movement had a distinct dynamic. In Rio, strikes were carried out by trade unions and even if the Workers’ Federation of Rio de Janeiro (the Federação Operária do Rio de Janeiro, FORJ), the city’s major union federation of revolutionary syndicalist orientation, did present a common list of demands, negotiations with employers were conducted separately by individual unions, many of which did not recognize the Federation as their representative. Meanwhile, in São Paulo, where repression was more intense, the reorganization of unions did not occur as swiftly as in Rio, so strikes were not organized based on the workplaces or certain economic sectors, but through the workers’ communities by neighbourhood associations. These were then brought together in a city-wide body called Comitê de Defesa Proletária (Committee of Proletarian Defence). This phenomenon probably contributed to the greater unity of São Paulo’s strike movement. Thus, the negotiation of a common list of demands presented to employers and to the state administration by the Committee of Proletarian Defence led to strikers’ collective acceptance of the final agreement with their employers and the government. Nevertheless, despite their differences, labour movements in both cities during this time experienced what may be seen as a more flexible and more pragmatic turn. This also applied to unions adhering to revolutionary syndicalism. The list of demands in São Paulo was a mix of labour, consumer, and political requests that was strikingly different from the usual agenda of direct action, a tendency that supposedly dominated organized labour in that city. At the same time, albeit indirectly, São Paulo’s unions established channel of negotiation with the state government (something openly rejected in previous conflicts). As for Rio, trade unions affiliated to a revolutionary syndicalist tradition and their leadership also acted with a discernable degree of pragmatism. All this might seem, at first sight, paradoxical: Were these mobilizations, after all, not connected to the great, international wave of revolutionary unrest at the end of World War I and, subsequently, to “1917”, with all the principles and high political stakes that it involved? Was this not an epoch of an abundance of “ideology” and a lack of “pragmatism”? However, as the Brazilian case illustrates, the ascendancy of “ideology” and “pragmatism” were not mutually exclusive: “Revolution”, above all the fear of revolution by those in power, also bred opportunities for reform, while the momentum of the mobilizations led its leaders to grasp these opportunities and seize the moment with whatever means seemed appropriate to achieve them.

During a strike in August 1917, as part of the ongoing dispute between direct action and pragmatic reformist unionism, the Shoemakers’ Union, affiliated with the syndicalist FORJ, saw the birth of a dissident organization called the Shoe Workers’ League, which included only industrial workers but omitted craftsmen.Footnote 49 While it officially professed a syndicalist allegiance, the League managed to reach an understanding with employers, with the mediation of the Chief of Police, which established higher wages, a fifty-two-hour work week, and a rule that employers should give workers two days’ notice before their dismissal.Footnote 50 The most important part of the negotiation, and an entirely new consequence of these talks, was the intention to constitute a commission, composed in equal parts by employers and employees, to discuss ongoing and future industrial conflicts. But the correspondence that the League exchanged in the following months with the Chief of Police, who had been transformed into a kind of guarantor of the deal, shows that employers were not respecting the terms of the agreement.Footnote 51 Although the Chief of Police of the Federal District was occasionally called upon to mediate labour conflicts, this was probably the first time that he had taken on such an institutionalized role.

Pragmatism now not only reigned in matters of trade union work, it also started to characterize some of the more political interventions of the union’s leaders. In April 1917, Pascoal Gravina, who had been a delegate to the 1913 Workers’ Congress, became president of the newly created General Union of Metal Workers (União Geral dos Metalúrgicos – UGM), again, a union of revolutionary syndicalist orientation. A few months later, he publicly supported Evaristo de Moraes, a lawyer retained by several different labour unions, as a candidate for the Chamber of Deputies, running as part of the Brazilian Socialist Party (one of the many parties organized under this denomination during this period).Footnote 52 After the episode, however, the UGM published a note insisting on syndicalist principles and forbidding any of its members to speak on the union’s behalf on such matters.Footnote 53

Gravina, however, was not the only one to flirt with electoral politics. In October 1915, the Graphic Workers’ Association of Rio de Janeiro (Associação Gráfica do Rio de Janeiro – AGRJ) was created after several years during which these workers were unorganized or were divided into different craft unions. The AGRJ originated from a coalition of direct action and reformist militants, with João Leuenroth, former member of the COB board and brother of the well-known anarchist Edgard Leuenroth, as its president until 1918. After a short interlude, in which the board was dominated by anarchists who, however, soon resigned, João Leuenroth once again became the association’s president in 1919. In that same year, he failed to win a seat the City Council. Both João Leuenroth and the previously mentioned Gravina had been known as anarchists until the late 1910s, and yet they turned to or at least flirted with electoral politics. In 1920, when anarchists decided to quit the association for good and create a competing union of their own,Footnote 54 Leuenroth remained.

Yet another piece of evidence demonstrating the flexible and pragmatic stance that unions tended to adopt during those years are the relations they cultivated with certain politicians, especially those who tried to pass laws regarding working conditions. Even during the preceding period, when anarchists and reformists still coexisted in the AGRJ, this association maintained close ties with city councillor Ernesto Garcez.Footnote 55 Thanks to Garcez, the AGRJ received a symbolic subvention from the city to aid the Professional School (Escola Profissional) it intended to establish and a gold medal to offer as a prize for “the most artistic work” in the Graphic Exhibition it organized.

One might argue, of course, that the AGRJ’s relationship with Garcez can be understood in light of the composition of the Association’s leadership, which included both reformists and anarchists. Nonetheless, Garcez also had relations with the Centro Cosmopolita (Cosmopolitan Centre), a union of workers in hotels, restaurants, and bars, which was affiliated with the FORJ and hence more clearly identified with syndicalism and direct action.Footnote 56 Acting with the agreement of the Centre, Garcez presented a bill establishing a twelve-hour workday (ten hours for those who worked in kitchens) with a weekly day off for workers in that sector. In December 1917, the bill was approved by the City Council and enacted in January of the following year.Footnote 57 Although the intransigent demand for an eight-hour workday was present in the resolutions of all workers’ congresses and was part of various strikes, this episode shows that, under certain circumstances, unions, despite their revolutionary syndicalist rhetoric (which ruled out any compromise on such a central issue, especially when reached through outside intermediation), would pursue any possible gain, even if it meant settling for results that fell short of goals once considered indispensable.

After the 1917 strike movement, which managed to attain a number of victories, repression became more intense, leading to the closure by police of the FORJ on the pretext of the need to preserve public order.Footnote 58 The following year, the number of strikes grew significantly againFootnote 59 and workers formed a new, equally revolutionary-syndicalist federation, the União Geral dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ General Union, UGT). News from international news agencies and greatly distorted by the local mainstream press offered limited knowledge of what was going in Russia, yet, as in other parts of South America, the idea of a revolution in which workers had actually taken power was received enthusiastically by many activists.Footnote 60 Especially anarchists tended to see the Revolution as their own (and did so, in view of the deep chasm dividing Bolsheviks and Anarchists, at the latest from the civil war on, for a remarkably long time). The journalist Astrojildo Pereira, by then an anarchist with a particular interest in Russian events, wrote that the Russian Bolsheviks’s programme, drafted already in 1905, was “in essence anarchist”.Footnote 61 Nevertheless, to some degree inspired by the Russian Revolution, in November 1918 an unlikely alliance of anarchists (including Pereira), trade union leaders linked to the UGT, and dissident politicians planned an insurrection (to start in Rio, but which they would spread to the whole country). The plan was to launch a general strike that would receive the support of military units. Strikers mainly included metal workers, textile workers (who had their own specific demands and remained on strike despite repression, even after the attempted uprising had failed), and a limited number of construction workers. The Army lieutenant who was supposed to serve as a liaison between the striking workers and military units proved to be an agent of the police who had infiltrated the workers’ movement. Consequently, the main leaders of the strike were arrested, the UGT and the three unions representing the sectors on strike were shut down, and the police applied further repressive measures to the entire labour movement.Footnote 62 For many labour activists, the insurrection was a government provocation to justify wide-scale repression.Footnote 63 Without doubt, several factors came together in this failed insurrection (which was partly planned as a putsch): Rio had a long tradition of popular revolts, the last one having taken place in 1904. At the same time, Brazilian anarchists had been rather reluctant to take up the local tradition and never assumed an insurrectionist stance (in sharp contrast with numerous partisans of Anarchism in Europe). Yet, the Russian experience and the powerful promises it seemed to carry might have led many of these activists to reconsider and see the moment come for such action.

Strikes were still numerous in 1919, but repression grew steadily and employers were more organized to resist workers’ demands. In place of the UGT, a new syndicalist federation named Labour Federation of Rio de Janeiro (Federação dos Trabalhadores do Rio de Janeiro, FTRJ) emerged, which proved to be even more pragmatic than previous federations by accepting affiliations with such trade unions as the AGRJ. The FTRJ even managed to launch a daily newspaper the following year, Voz do Povo.

The Decline of Revolutionary Syndicalism

In March 1920, a strike broke out at the Leopoldina Railways,Footnote 64 a strike which was to become a particular challenge to labour in many ways. Syndicalist principles were once again combined with pragmatism, and the strike became an arena in which the dispute between different tendencies seeking to influence the movement played out fully.

Initially, a list of demands containing points that ranged from wage increases and better working conditions to union control over conditions in railroad workshops was presented to the company by a workers’ association formed in the town of Além Paraíba (in the state of Minas Gerais), which was part of the railroad’s network. The company did not bother to respond to these demands and, shortly thereafter, workers in Rio formed another organization, the Leopoldina Employees’ Union (União dos Empregados da Leopoldina). The new union endorsed the existing list of demands and agreed on a date to strike. The resulting strike was not limited to the city of Rio de Janeiro, but rather reached the entire railroad network in different states. From the outset, the company refused to engage in direct talks with union representatives, so some kind of state mediation seemed inevitable, a task carried out by the Minister of Transportation and Public Works. Despite the minister’s proclaimed intention of an negotiated ending of the conflict, the government provided the company with military personnel to operate the trains. As negotiations stalled, the strike took on a new dimension when an impressive number of other trades and industries entered into solidarity action, backed by the syndicalist FTRJ as well as the particularly reformist Vehicle Drivers’ Federation. Rio was paralyzed as the strike extended from the city’s transportation to its bakeries, restaurants, etc., even including the street cleaners. Voz do Povo, the FTRJ’s daily, covered the events closely. After four days of what was nearly a general strike (and was the last great strike of the period), police and army launched a massive wave of repression, resulting in the arrests of over 2,000 strikers and the invasion of the headquarters of the unions involved. To justify the repression, the government alleged that a Bolshevik conspiracy lay behind the strike movement.Footnote 65

In the meantime, the Leopoldina Employees Union reached an agreement with the company, with the mediation of the FMB that had abstained from joining the strike. This Federation had, by its own initiative, from the beginning tried to reach an agreement to end the strike, securing from the President of the Republic, Epitácio Lindolfo da Silva Pessoa (1919–1922), the release of some of the arrested strikers before the strike ended. The final agreement, concluded with the President of the Republic acting as guarantor, did not obtain the wage increase that had been the main reason for the strike, but even under these difficult circumstances the workers did gain some concessions, such as the release of all imprisoned strikers, the re-employment of fired strikers, and the promise that nobody would be subject to punishment. Both the Drivers’ Federation and the FTRJ considered the agreement to be a form of treason and criticized the Leopoldina Employee’s Union for negotiating and agreeing to it. On its part, the railroad company never complied entirely with the terms of the agreement.Footnote 66

This strike not only represented a turning point in Rio de Janeiro’s labour movement, just some weeks before a new workers’ congress was held, but it also shows that reformist policies could present themselves in different ways and that certain groups, notwithstanding their identification with “revolutionary syndicalism” or “reformism”, were more eager than others to compromise with the government. It is necessary to stress, nonetheless, that during the Brazilian First Republic regional differences played a central role with considerable variation in the conditions under which these unions acted. And in Rio de Janeiro, despite the repressive policies that were similar to those in the rest of Brazil, possibilities for negotiation and mediation were greater than those found in São Paulo, where the authorities followed a repressive approach much more consistently. In part, this can be explained by the fact that the national government was installed in a port city with a long tradition of unruliness and conflict that could not be managed exclusively through force.

When the Third Brazilian Workers’ Congress met in April 1920 (here, again, the nomenclature followed the revolutionary syndicalist rather than the reformist mode of counting), participants had to deal with the changes that labour was undergoing during those years. Although reaffirming the resolutions passed at the two previous congresses, its own resolutions adopted a more pragmatic tone, recognizing the different situations encountered in various economic sectors. More remarkably, the Third Brazilian Workers’ Congress, while sustaining the principles of direct action, saw the adjective “revolutionary” disappear from its documents yet again. This congress was the most representative of all up to that time, with seventy-two delegations present, thirty-two of which were from the Federal District.Footnote 67 The opening session was attended by 103 delegates.Footnote 68 For the first time, different ideological tendencies were present, from reformist through revolutionary syndicalist to anarchist, although in key areas such as the port, dock, and maritime workers, not all unions sent representatives.

The proposals presented tried to obtain a minimum agreement of the majority of the delegates, sometimes by simply adopting a rhetoric of the least common denominator that would seem acceptable for other delegates. The AGRJ, for instance, presented ideas that fell under the title “union neutrality”, proposing that unions should avoid all involvement in politics, including ideologies such as anarchism (which at first sight seemed a proposition following the traditional stance of revolutionary syndicalism), while, at the same time, proposing that workers engage in politics outside the unions. Even the references used to give credence to this proposition were inaccurate: The authors attributed the endorsement of such a policy to Félicien Challaye, a French philosophy professor who wrote a book on revolutionary and reformist syndicalism, when, in fact, the quotations, cited in Challaye’s work, came from a French socialist, Albert Thomas, who had been Minister of Armament during the war. Although Thomas’s name is never mentioned in the congress proceedings, it was his works that Challaye used to illustrate the reformist position, in the same way as he quoted revolutionary syndicalists to illustrate theirs. Even the title of the proposal that called for “union neutrality” came from an article by Thomas.Footnote 69

Apparently, the congress tried to carry out the impossible task of obtaining a minimum consensus among organized labour while reaffirming some of the main principles of revolutionary syndicalism, and while a pragmatic approach held sway in all major issues. The congress did not stop the erosion of the prestige that revolutionary syndicalism once had among anarchists. In the years that followed, they preferred to adopt the position that unions should assume an anarchist programme, a proposal that had been defeated in the past and which bore all the hallmarks of a self-isolating minority position. At the same time, those anarchists who had turned to other experiences, such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and particularly the Russian Revolution, ultimately formed the Communist Party (Partido Comunista do Brasil) in 1922.

A Shared Culture?

At first glance, the orientations, which are conventionally labelled as direct action and reformism, appear to have been completely incompatible with and clearly opposed to each other. Yet, they did share some common ground, starting with a number of more obvious commonalities, such as the importance attributed to working-class education, temperance, the demand for an eight-hour work day, and the celebration of May Day.

The shared appreciation for certain symbolic practices could lead to surprising, even amusing episodes: In April 1913, for instance, a dozen working-class associations, representing both major ideological tendencies present in Rio de Janeiro’s labour movement, sent a letter do the Chief of Police protesting against a carnival that the Club dos Fenianos (Fenians’ Club)Footnote 70 planned to hold on May Day, an act that was supposed to honour the working classes. The authors of this letter judged the celebration an affront to the day universally dedicated to the struggle against exploitation. Some days after receiving the protest letter, the Chief of Police invited a delegation of workers to discuss the matter and assured them he would not authorize the carnival.Footnote 71 Under other circumstances, one could hardly imagine anarchists or revolutionary syndicalists seeking the Chief of Police’s help; yet, this seemed a matter, despite its symbolical character, too important not to use all means at hand.

As this article has highlighted for Rio de Janeiro’s labour movement between the beginning of the twentieth century and 1920, the boundaries between the revolutionary syndicalist, anarchist, and reformist orientations could be quite porous. This not only applied to symbolical matters and shared demands, but also held true for those issues seen as absolutely divisive, such as the question of negotiation with and the intermediation through the state, the involvement in electoral politics, the achievement of concrete gains falling short of long-held sine qua non-demands, or the building of a professionalized organization. Here, the history of the labour movement of countries seen as “typical” (and where a clear-cut separation into different spheres is supposed to have happened in the 1890s at the latest) can obfuscate the degree to which the different currents in other world regions were densely interwoven for much longer. In the case of Rio, there are manifold moments when the revolutionary syndicalist and reformist stances intermingled, and when leading individual activists or whole organizations proceeded to change their practices (while often maintaining the rhetorical claims). This intermingling has seen a certain development over time: While in the years from the Congress in 1906 positions seemed to be entrenched, the recovery of the movement from 1917 onwards and a subsequent three-year cycle of struggles have witnessed all currents acting under more pragmatic and flexible auspices, swiftly reacting to the opportunities offered. Not coincidentally, this turn towards pragmatism, especially among adherents of revolutionary syndicalism, happened in a period considered in more traditional accounts as being under the signature of “revolution”. However, both dynamics – the revolutionary and the pragmatic – were not mutually exclusive, the former (or, more precisely, the threat of it) opening space for the latter. In Rio, it was those currents that had long borne the attribute “revolutionary” in their commitment as unionists that, in particular, grasped this accurately. This was favoured by a local version of revolutionary syndicalism that, in comparison to other Brazilian cities as well as internationally, had been relatively moderate from the beginning, and a political landscape that (compared to São Paulo) had always offered more opportunities for gradual gains.

Despite different interpretations, defenders of direct action could thus adopt reformist stances (and vice versa). Yet, the commonalities between the different currents had roots that were deeper than the issues of strategic orientation and political demands: Both currents shared certain beliefs and practices – a common culture – that, in most cases, were older than the division between the two currents of labour activism. As early as the mid-nineteenth century, working-class associations supported the importance of workers’ education, whether in the form of formal or professional education. Thus, it was quite common for trade unions, at least in their by-laws, to propose the creation of libraries, courses, and schools, as we have previously seen in the case of the AGRJ. In 1913, another union, the Sailors and Rowers’ Association, declared in its by-laws that it should establish basic educational classes, a library and, eventually, professional training for its associates, all these proposals being subject to the availability of financial resources.Footnote 72

May Day was a date that both direct action activists and partisans of reformism shared, and their speeches would refer to a common repertoire associated with the occasion: remembrance of the “Chicago martyrs”, a universal stoppage of work, the fight for the eight-hour work day, and so forth. This occasion simultaneously reinforced unity and made important differences visible in the way the day should be observed. Direct action preferred sober and clearly class-oriented meetings, even if plays, poetry reading, and musical presentations did occur, while reformism tended to prefer larger-scale public demonstrations and parades with military fanfare and the presence of politicians. Yet, even at moments when relations between the two currents were particularly tense, gestures of conciliation were made: In 1913, during the period between the two competing workers’ congresses, the socialist cigarette worker Mariano Garcia inaugurated a Workers’ Column in the daily newspaper A Epoca, which, on the occasion of Mayday, he also opened for anarchists to set out their ideas about the date.Footnote 73 Conversely, two days later, in Rio, anarchist leader Edgard Leuenroth, taking part in FORJ’s May Day activities, attended a session organized by the Workers’ League of the Federal District, the association that was directly responsible for the 1912 Congress so bitterly criticized by anarchists.Footnote 74 Thus, even before revolutionary syndicalist practice became so pragmatic by the end of the 1910s that it could barely be distinguished from reformism, it did, ultimately, share a common culture with the other currents of the labour movement.

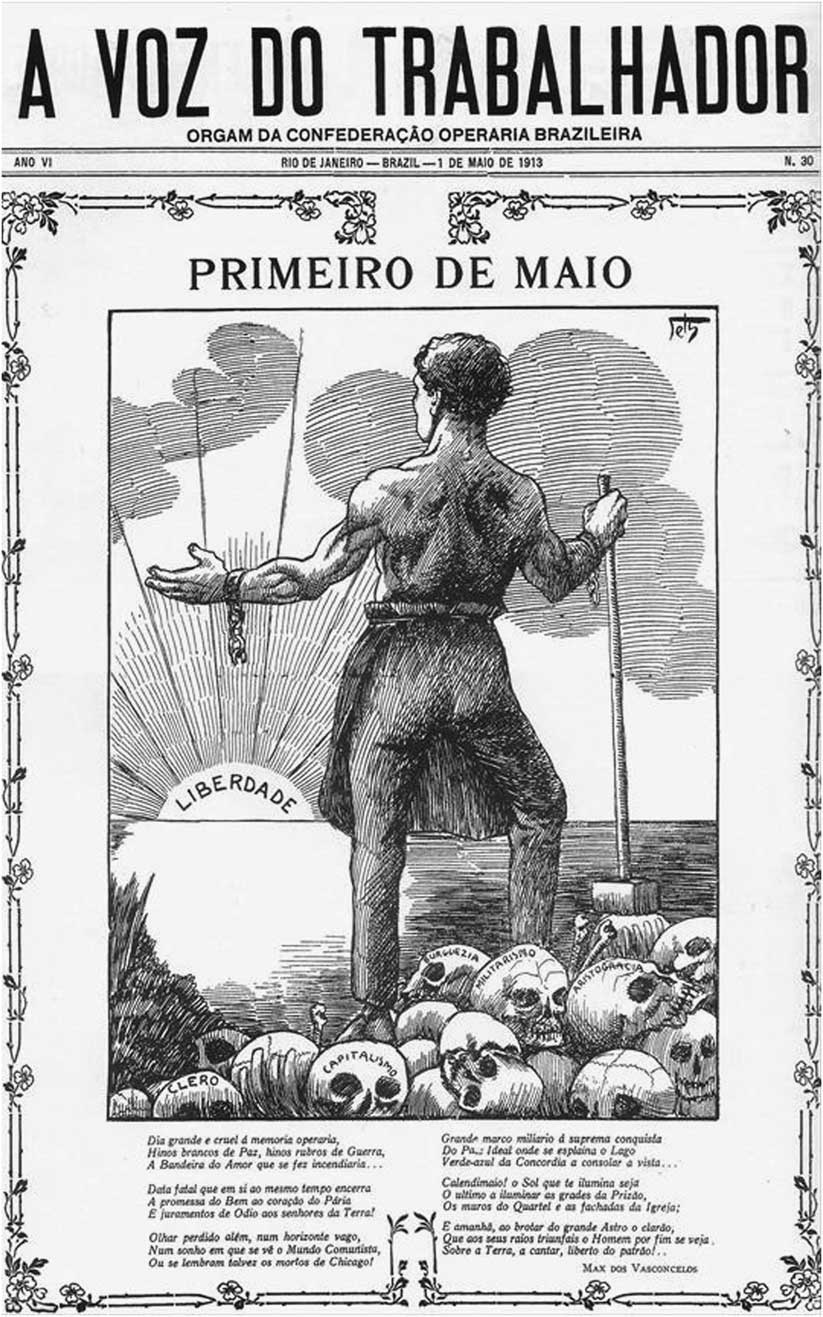

Figure 1 First page of May Day’s 1913 edition of A Voz do Trabalhador, newspaper of the revolutionary syndicalist Confederação Operária Brasileira [Brazilian Workers’ Confederation]. A Voz do Trabalhador, Rio de Janeiro, 1st May 1913, p. 1. Collection Arquivo Edgard Leuenroth/IFCH/UNICAMP, J/0013.

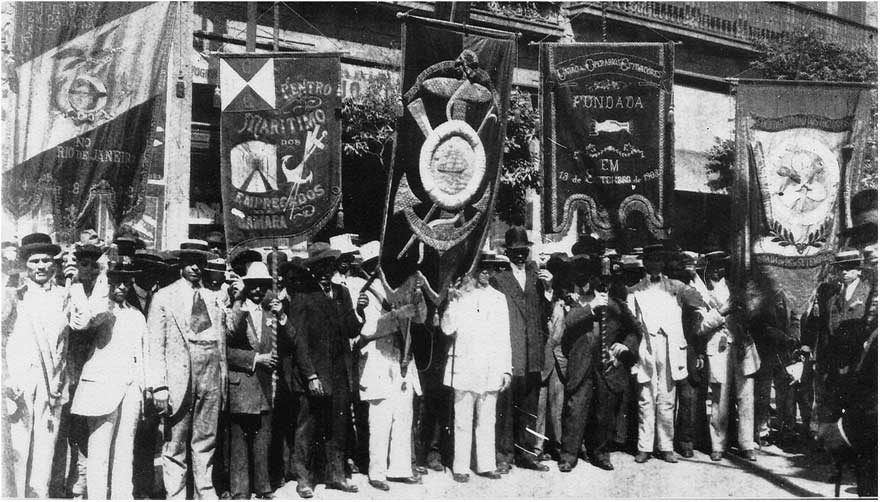

Figure 2 Members of reformist trade-unions on their way to the May Day 1913 demonstration. Fon-fon, Rio de Janeiro, 10 May 1913 [no page number]. Collection Arquivo Edgard Leuenroth/IFCH/UNICAMP, R/0359.

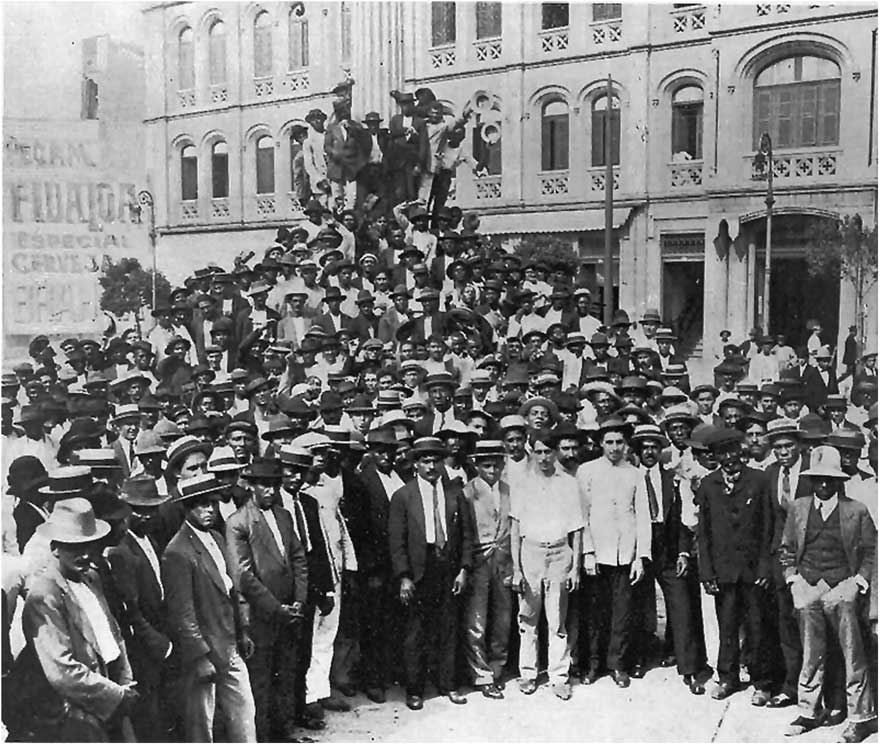

Figure 3 Maritime workers demonstration called by the Brazilian Maritime Federation against the lease of Brazilian Merchant ships. O Malho, Rio de Janeiro, 24 March 1917 [no page number]. Collection Arquivo Edgard Leuenroth/IFCH/UNICAMP, R/0363.