Introduction

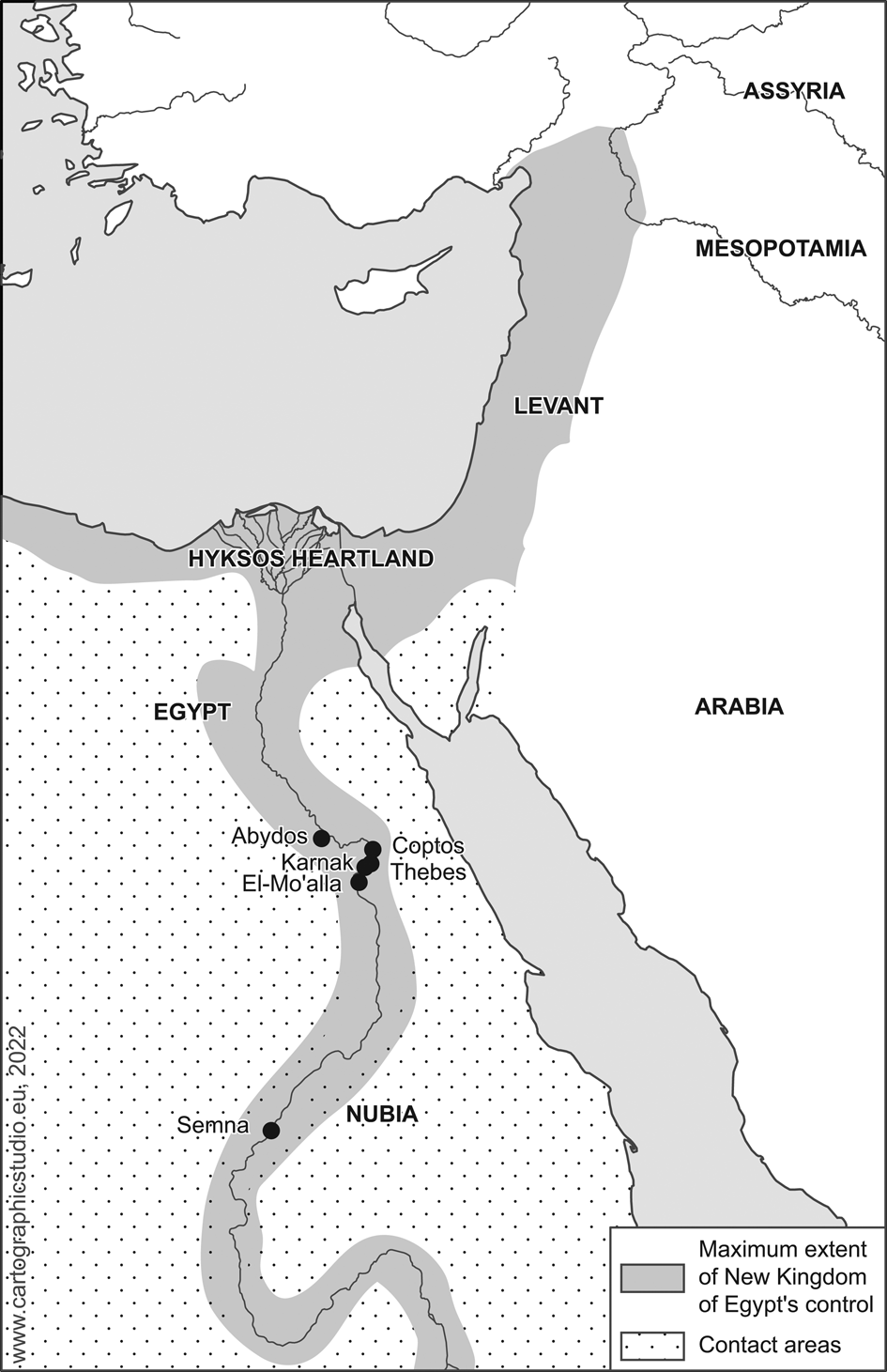

This paper looks at two texts of the Egyptian New Kingdom (c.1550–1069 BCE, Figure 1),Footnote 1 both concerned with questions of good government and, more specifically, labour regulation, including combating the unauthorized diverting of manpower and resources from state-sanctioned projects. These texts are two royal decree stelae: the Karnak Decree of Horemheb (c.1323–1295 BCE)Footnote 2 and the Nauri Decree of Seti I (c.1290 BCE),Footnote 3 which together represent the oldest Egyptian texts explicitly concerned with the legal dimension of managing the workforce. After providing a summary of the historical context, this paper will outline each text's key content and stylistic features before investigating their possible origins. As will be demonstrated, the predominant sentence structure in each text has Egyptian precursors of significantly greater age. The same cannot be said of the sanctions specified in the content. Instead, these align more closely with the contemporary punitive tradition of Mesopotamia, and such an alignment is unlikely to be coincidental given the close contact between Egypt and the broader Near East at that time. Hence, it will be shown that the texts imbue a native Egyptian structure – reflecting a broader underlying intellectual tradition – with meanings and regulations imported from elsewhere. In turn, this was likely central to their purpose of achieving more efficient labour regulation by enforcing stricter rules for non-compliance while simultaneously maintaining a veneer of Egyptian authenticity in line with official state ideology.

Figure 1. Map showing all ancient Egyptian sites mentioned in the text.

Historical Context: Socio-Political Turbulence Against a Backdrop of Imperial Expansion

The four decades preceding the reigns of Horemheb and his successor, Seti I, were characterized by political, religious, and dynastic tumult. The upheavals began with Egypt witnessing the abolition of its traditional pantheon under the rule of Akhenaten (r. 1352–1336 BCE), who introduced an exclusive focus on worshipping the sun disc instead and also saw the royal court relocated to a new capital city built at vast expense on a previously uninhabited desert site.Footnote 4 This new religion and capital both promptly collapsed during the subsequent reign of Tutankhamun (r. 1336–1327 BCE), who was throughout his reign a child king suffering from severe ill health and physical deformities, and whose pharaonic power was almost certainly wielded by others on his behalf.Footnote 5 Furthermore, he died childless, with the throne passing to an elderly royal advisor, Ay (r. 1327–1323 BCE). Ay himself was unable to secure the succession for his designated heir, Nakhtmin, and was instead succeeded by another leading courtier, Horemheb (r. 1323–1295 BCE), with whom Ay had endured a fractious relationship.Footnote 6 Under Horemheb's rule, the Egyptian government again altered its course, with Akhenaten, Tutankhamun, and Ay denounced as heretical for not breaking with the past in sufficiently radical fashion. To complicate matters further, all this political instability appears to have been exacerbated by malaria and plague outbreaks,Footnote 7 as well as famine.Footnote 8 All of this would almost certainly have negatively impacted the prestige of successive Egyptian kings, who faced an acute crisis of legitimacy.

At the same time, while individual kings struggled to assert themselves, Egypt as a polity was arguably “wealthier and more powerful than it had ever been before”.Footnote 9 Despite the internal chaos, the country was nearing its maximum territorial extent, comprising both a military and trading empire stretching from various vassal states in the Levant to south Sudan.Footnote 10 This presented rulers with both a challenge and an opportunity: on the one hand, internecine strife had made the monarchy weak; on the other hand, a king who could successfully restore stability and royal power had the prospect of ruling over what was at the time one of the world's largest and wealthiest states, while also complying with Egypt's long-standing ideological trope of a new monarch restoring order.Footnote 11 Effective regulation of labour and control of the workforce would inevitably have to be part of this.

Karnak Decree of Horemheb

The Karnak Decree of Horemheb is the older of the two texts addressed here and was found carved on a large stela at the Karnak temple complex in Thebes, Upper Egypt. After the upheavals described above, the reign of Horemheb represented a return to relative political and religious stability.Footnote 12 Thus, it is likely that – especially given his lack of royal descent and difficult relationship with the previous pharaoh, Ay – one of Horemheb's most pressing priorities upon acceding to the throne was to reassert the primacy of his royal authority. The Karnak decree was, therefore, most probably designed to shore up the legitimacy of both the royal office as an institution and of Horemheb specifically as its rightful holder.Footnote 13

The decree text provides a symbolic affirmation of the pharaoh's commitment to maintaining order in Egypt while also laying down practical rules for how this was to be done. It begins with a relatively short preamble describing how Horemheb possesses divine favour, and how he will use his royal status to establish justice in the land. This is followed by the main decree, consisting of provisions condemning a range of illegal practices perpetrated by royal officials abusing their power. Offences include seizing boats and wood belonging to private individuals (i.e. non-state property), seizing labourers working on private projects, seizing animal skins from the rural population, demanding unjustifiably high tax payments, and taking grain, fruit, vegetables, and linen from private estates. A key concern of the text is thus the protection of private wealth and property, and one form of such wealth is privately owned labour. The following passage illustrates the nature of the labour concerns raised in the decree:Footnote 14

nɜ n sd̠m.(w)-cš ỉt̠ pɜ ḥm tɜ ḥm.t n nmḥy mtw nɜ n sd̠m.(w)-cš hɜb.w m wp.wt r t̠ɜ kt̠ ḥr hrw-6 hrw-7 ỉw bw rḫ.tw šm.t m-dỉ=sn m wst̠n r-nty ḫn pw n ḥɜw pɜy m rdỉ ỉr.tw m-mỉt.t grw

The attendantsFootnote 15 grab the male and female servant(s) of the private party, and the attendants send them on assignments (wp.wt)Footnote 16 to gather saffron for six days or seven days, without them having permission to go freely. Thus, this is a matter of excess. Do not allow such action anymore.

Judging from content earlier in the decree, it is apparent that the “attendants” in question are state officials who have – at least in Horemheb's eyes – become overmighty and are threatening to strip the non-state sector of the Egyptian economy of its labour capacity. The provision of the decree, therefore, effectively amounts to a regulation of conscription. To counter the apparent threat of non-state actors carrying out such conscription for labour projects, the text decrees that these offenders should be dealt with as follows:Footnote 17

ỉr sd̠m.(w) nb n ct ḥnkt pr-cɜ cnḫ.(w) wd̠ɜ.(w) snb.(w) nty ỉw.tw r sd̠m r-d̠d st ḥr kfc r t̠ɜ kt̠ grw ḥnc nty ky ỉỉ.t r smỉ r-d̠d ỉt̠.(w) pɜy=ỉ ḥm tɜy=ỉ ḥm.t ỉn=f ỉr.tw hp r=f m swɜ fnd̠=f dỉ.w r T̠ɜrw ḥnc šd.(t) pɜ bɜk n pɜ ḥm tɜ ḥm.t m hrw nb ỉrr=f m-dỉ=f

As for every attendant of the chamber of offerings of Pharaoh (l. p. h.)Footnote 18 about whom one will hear that they are requisitioning (people) to gather saffron, moreover with somebody coming to report: “my male servant and/or my female servant have been seized by him”, the hp-lawFootnote 19 will be enforced against him in severing his nose, deporting him to Tjaru,Footnote 20 and confiscating the (fruits of) the work done by the male servant and/or female servant on every day that he worked for him.

The decree also deals with a series of related offences that are not strictly concerned with regulating the provision of manpower but do directly address the abuse of state-sanctioned authority and the misappropriation of resources associated with the labour regime. For instance, in the section on the extortion of animal skins, the following provision is made:Footnote 21

ỉr cnḫ nb n mšc ntw ỉw.tw r sd̠m r-d̠d sw ḥr šm.t ḥr nḥm dḥr.w grw šɜc m pɜ hrw ỉr.tw hp r=f m ḥw.(t)=f m sḫ-100 wbn.w-sd-5 ḥnc šd.(t) pɜ dḥr ỉt̠.n=f m-dỉ=f m-t̠ɜ.w

As for any soldier about whom one will hear that he is still coming to seize animal skins up to this day, the hp-law will be enforced against him in striking him with 100 stick blows and five open wounds, and confiscating the animal skin which he seized for himself through theft.

The final part of the text is a self-laudatory royal narrative reinforcing the themes set out in the introduction, wherein Horemheb recapitulates how he established justice in Egypt, appointed fair officials to judge cases, mercilessly crushed corruption, and ultimately caused the land to flourish. The king pledges to maintain good order and rule in accordance with the established custom in the future and sets out various ceremonial and administrative duties, which he intends to assign to his subordinates. The text ends with an affirmation of the king's divinity, likening his radiance to that of the sun and stressing the importance of his instructions being followed. The individual judicial provisions of the decree are therefore shown to effectively be a case study demonstrating the wide-ranging justice dispensed by the king – and labour regulation is part of that precept.

Nauri Decree of Seti I

Seti I promulgated his decree, carved into a monumental clifftop stela at the site of Nauri in Egyptian-occupied Nubia (Figure 2), perhaps only two decades after the Horemheb decree and almost certainly at a time when the release of the earlier text was still in living memory. The circumstances of his accession were also not dissimilar: while, unlike Horemheb, Seti I was the son of a king, his father, Ramesses I, had enjoyed an exceptionally brief reign of only one year and was not of royal blood. Therefore, Horemheb's concerns about royal legitimacy probably applied, to some extent, to Seti I's motives, too, even if he was inheriting a country after a period of rather more stable government compared to the environment that Horemheb had faced. Even so, given its overall temporal proximity to the Horemheb text, it is perhaps unsurprising that the Nauri decree is generally similar in content to the Horemheb decree, with the difference that it relates specifically to actions in and around the king's temple foundation (termed “Menmaatre, heart content in Abydos”). Like the Horemheb text, the Nauri decree begins with a preamble – this time of somewhat greater length – emphasizing the credentials of the king as the defender of the realm and pious servant of the gods. In particular, it stresses how these good qualities are brought out through the king's devotion to the temple he has constructed at Abydos. The text then moves to the main body of the decree, condemning a wide variety of practices, including the seizing of labourers working on the royal temple estate for unrelated purposes, the arbitrary detaining of boats, tampering with fields of the royal temple estate, seizing cattle and other animals belonging to the estate, and unspecified wrongful conduct against hunters, fishermen, and tenants of the estate.

Figure 2. Upper register of the Nauri decree stela, depicting Seti I offering to the gods an effigy symbolizing justice.

Its concerns about people – or, more specifically, workers with duties on the estate – being unfairly forced into unrelated labour are phrased in a similar way to the Horemheb decree. For instance, among the stated aims of the decree is:Footnote 22

r tm rdỉ.t ỉt̠ɜ.tw rmt̠ nb n pr pn m kfc.w m w n w m bryt m bḥw n skɜ m bḥw n cwɜy ỉn sɜ-nsw nb ḥry-pd̠.t nb ḥɜ.ty-c nb rwd̠.w nb rmt̠ nb hɜb.w m wp.t r Kɜš

To prevent any person of this estate being taken as a captive from district to district, by obligatory service (bryt)Footnote 23 or by forced labour (bḥw)Footnote 24 of ploughing, or by forced labour (bḥw) of reaping by any King's Son (i.e. viceroy), any troop-commander, any count, any agent or any person sent on an assignment (wp.t) to Kush.

When describing specific offences and punishments relating to illegal appropriation of labour, the Nauri decree goes into more detail than the Horemheb decree. The main block of text about this is as follows, characterized by lengthy clauses and a high degree of specificity in setting out the punishments due:Footnote 25

ỉrSIC sɜ-nsw n Kɜš nb ḥry-pd̠.t nb ḥɜ.ty-c nb rwd̠.w nb rmt̠ nb nty ỉw=f r ỉt̠ɜ rmt̠ nb n tɜ ḥw.t Mn-Mɜc.t-Rc ỉb hr.w m 3bd̠t m kfc.w m w n w m bryt m bḥw n skɜ m bḥw n cwɜy m m-mỉt.t pɜ nty iw=f r ỉt̠ɜ s.(t)-ḥm.t nb n rmt̠ nb n tɜ ḥw.t Mn-Mɜc.t-Rc ỉb hr.w m 3bd̠t m-mỉt.t nɜy=sn ḥm.w m kfc.w r ỉr.t wp.t nb nty m tɜ r d̠r=f m-mỉt.t kd̠n nb ḥry-ỉḥ.w nb rmt̠ nb n pr-nsw hɜb.(w) m wp.t nb n pr-cɜ cnḫ.(w) wd̠ɜ.(w) snb.(w) nty ỉw=f r ỉt̠ɜ rmt̠ nb n tɜ ḥw.t Mn-Mɜc.t-Rc ỉb hr.w m 3bd̠t m w n w m bryt m bḥw n skɜ m bḥw n cwɜy m-mỉt.t r ỉr.t wp.t nb ỉr.tw hp r=f m ḥw.t=f m sḫ-200 wbn.w-sd-5 ḥnc šd.(t) bɜk.w n pɜ rmt̠ n tɜ ḥw.t Mn-Mɜc.t-Rc ỉb hr.w m 3bd̠t m-c=f m hrw nb nty iw=f r ỉr.(t)=f m-c=f dd.(w) r tɜ ḥw.t Mn-Mɜc.t-Rc ỉb hr.w m 3bd̠t

As for any King's Son (i.e. viceroy), any troop-commander, any count, any agent or any person who will take any person of the FoundationFootnote 26 as a captive from district to district by obligatory service (bryt) or by forced labour (bḥw) of ploughing, or by forced labour (bḥw) of reaping, likewise the one who will take any wife of any person of the Foundation, and likewise their dependents, as captives to do any assignment (wp.t) which is in the entire land, and likewise any charioteer, any overseer of herds, or any person of the royal estate sent on any assignment (wp.t) of Pharaoh (l. p. h) who will take any person of the Foundation from district to district by obligatory service (bryt) or by forced labour (bḥw) of ploughing, or by forced labour (bḥw) of reaping, and likewise to do any assignment (wp.t), the hp-law shall be done (i.e. enforced) against him by beating him with 200 blows and five inflicted wounds, together with confiscating the (fruits of) the work of the people of the Foundation, from him with regards to every day which he will spend with him, it being given to the Foundation.

Other punishments prescribed in the decree include severing the ears and nose, impalement, and compulsory labour for both convicts and their families.Footnote 27 While not all of these are strictly related to violations related to the provision of human labour, all are in some way associated with resource management or the logistics thereof, and are thus directly related to the work environment. At the end of the decree, just as with the Horemheb text, there is a short epilogue stressing that the royal instructions provided earlier reflect the divine will and that they, therefore, evince the responsible nature of the king's rule.

Overall, the Horemheb and Nauri decrees are very similar, both in style and content. Stylistically, both have a tripartite structure, with the main body of the text – the decree proper, including the discussion of labour regulation – illustrating the justice, wisdom, and divine favour of the monarch, which is extolled explicitly in the prologue and re-emphasized by the ring composition achieved through these same themes being highlighted once more at the end. In terms of content, they share both a common set of behaviours, which they seek to curtail, namely, abuses in and around labour misappropriation, and similar sets of punishments marked by a violent, highly physical nature – although the later decree is more detailed and seemingly more brutal in its provisions.

Differences can also be observed with regard to the type of labour being regulated: in the Horemheb text, emphasis is placed on curbing abuse of authority by royal officials appropriating private labour and the fruits thereof, while the Nauri text protects labour that is itself tied to a royal foundation, although the offenders are still royal officials. Given the slightly later date of the Nauri text, one might speculate that the shift in focus towards specifically protecting royal labour is linked to the crown having, by that point, accrued additional estates and resources that previously did not need protecting because they were not there. Horemheb inherited a crown weakened by decades of political chaos, and it would have been logical for him to rely on private labour as part of his rebuilding mission. Seti I may not have had to rely on the private sector as much, as he would have benefited from the relative stability of what had come before him. Nonetheless, such a hypothesis must not be overstated: first, the comparison is imperfect since neither text is perfectly preserved, with the Horemheb decree, in particular, missing many fragments, and second, the existing labour management differences might be down to the specific functions of the individual decrees rather than any broader socio-economic phenomenon: the function of the Nauri text was to protect a particular royal foundation and its workers, whereas the Horemheb text was more concerned with remedying labour management ills at large. The fact that these texts had different goals might suggest a change in the situation, but it cannot prove it. On the other hand, the similarities between the texts, as revealed by their common structure, the offences targeted, and the punishments deployed, cannot be subjected to similar doubt. Nor can the promulgation of such decrees so close to one another chronologically be convincingly attributed to coincidence, especially bearing in mind that no comparable text of labour regulation had ever been produced before.

Precursors: How Did These Forms of Labour Management Come About?

The Horemheb and Nauri decrees can be considered among the oldest records of tightly defined legislation relating to labour management in ancient Egypt. However, while they are certainly innovative – and, indeed, unique – in this regard, they contain numerous traits that are also evident in earlier documents. Of great significance here is the grammatical structure employed in setting out the legal provisions in the decrees: it is the protasis-apodosis conditional sentence, wherein the execution of the punishment laid out in the second clause (the apodosis) is dependent on the offence specified in the first clause (the protasis) on both a broader conceptual and a narrower syntactic level. Thus, the two texts are related not only in law but also in grammar.

The roots of the protasis-apodosis formulation can be traced to as early as the Old Kingdom, over an entire millennium earlier. We already see something stylistically and conceptually similar in a decree on a stela of King Neferirkare (r. 2475–2455 BCE), although – as will be discussed – the level of detail and legal sophistication provided is not quite comparable. The text, which is unfortunately not fully preserved, gives instructions about how certain classes of delinquent are to be treated, and its shorter clauses make the individual provisions easy to break down into their constituent protasis-apodosis components:Footnote 28

ỉr s nb n š.t ỉt̠.ty=fy ḥm.w-nt̠r nb nty.w ḥr ɜḥ.t nt̠rỉ wcb.t=sn ḥr=s m š.t tw r rɜ-c.wy ḥnc kɜ.t nb.t n.t š.t mɜc=k sw r ḥw.t-wr.t dỉ r kɜ.t… mɜt̠ skɜ ỉt bd.t

As for any man of the district who will take any ḥm-nt̠r-priests who are upon the sacred land upon which religious service is conducted in this district for corvée labour (rɜ-c.wy) together with any work of the district,

Protasis: offenders/offences committed

Protasis: offenders/offences committed

you shall lead him to the great enclosure (ḥw.t-wr.t) and put (him) to work […] granite and harvesting barley and emmer.

Apodosis: envisaged sanction

ỉr s nb n š.t ỉt̠.ty=fy mr.t nt.t ḥr ɜḥ.t nt̠rỉ n.t š.t r rɜ-c.wy ḥnc kɜ.t nb.t n.t š.t mɜc=k sw r ḥw.t-wr.t dỉ r kɜ.t…mɜt̠ skɜ ỉt bd.t

As for any man of the district who will take mr.t-people [tenants?] who are upon the sacred land of the district for corvée labour (rɜ-c.wy) together with any work of the district,

Protasis: offenders/offences

committed

you shall lead him to the great enclosure (ḥw.t-wr.t) and put [him] to work […] granite and harvesting barley and emmer.

Apodosis: envisaged sanction

The Neferirkare text, while perhaps the most explicitly connected to labour management, appears to have been part of a broader tradition of Old Kingdom rulers issuing decrees of this sort, intending to set out punitive consequences for various offenders operating on royal estates. Other examples, all dating to the twenty-third and twenty-second centuries BCE, include the Edicts of Pepi II (Coptos B), Neferkauhor (Coptos I), and Demedjibtawy (Coptos R).Footnote 29 However, in these much older attestations, the legal framework associated with the New Kingdom stelae has yet to develop. Instead of alluding to a concrete concept of hp-law as justification for punishment, the Neferirkare text and other decrees in its tradition make far more generic claims, such as that seizing parts of the workforce has consequences for the perpetrator, who is himself reduced to unfree labour. Instead of being framed as legislation – a set of provisions governed by law – these Old Kingdom clauses are royal instructions, probably not part of any wider corpus and designed for ad hoc use but nonetheless serving as important reminders of the significance of labour regulation even at this early time. It is, however, noteworthy that the New Kingdom decrees prescribe harsh corporal punishments alongside forced labour – providing a level of detail comprehensive enough to count individual blows and wounds – whereas the Old Kingdom text makes no mention of corporal punishments whatsoever and may indicate a more flexible approach to determining sanctions, which would be in keeping with an ad hoc style. On the other hand, the structure characteristic of the New Kingdom decrees is already fully formed, with clauses beginning with the same conditional construction (beginning with the introductory ỉr).

It should also be emphasized that while the Old Kingdom decrees are comparatively rare examples of early protasis-apodosis texts that discuss labour regulation in some form, more generally, the protasis-apodosis style of formulation was common across multiple avenues of Egyptian thought. Prominent examples of its use are found in threats to potential tomb desecrators, as illustrated, for instance, in the tomb of the prominent local governor Ankhtifi at El-Mo'alla, dating to the First Intermediate Period (c.2100 BCE):Footnote 30

ỉr ḥḳɜ nb ḥḳɜ.t(y)=f(y) m Ḥfɜt ỉr.t(y)=fy c d̠w bỉn r dỉ tn r mn.w nb.w n.w pr pn sḫ.t ḫpš=f n Ḥmn

As for any ruler who will rule in Mo'alla and who will carry out a bad and evil act against this coffin and any monument of this tomb, his arm will be cut off for Hemen.

It is profoundly unclear whether the wrongdoer was actually expected to be punished by physical severance of the arm, as opposed to the sanction being an allusion to a divine curse.Footnote 31 Still, this is another illustration of cause and consequence being framed in protasis-apodosis terms as early as the third millennium BCE, and numerous curses of a similar structure persisted throughout the second millennium BCE.Footnote 32 These did not have to prescribe violent punishments. For instance, a famous example is the exhortation made by Middle Kingdom ruler Senusret III (r. 1870–1831 BCE) to his children on his Second Semna Stela demarcating the Egyptian border with Nubia, where unsatisfactory children face the threat of being disowned:Footnote 33

ỉr gr.t sɜ=ỉ nb srwd̠.t(y)=fy tɜš pn ỉr.n Ḥm=ỉ sɜ=ỉ pw ms.tw=f n Ḥm=ỉ tw.t sɜ nd̠.ty ỉt=f ỉr gr.t fḫ.t(y)=fy sw tm.ty=fy cḥɜ ḥr=f n sɜ=ỉ ỉs n ms.tw=f ỉs n=ỉ

Now, as for any son of mine who will strengthen this border which my Majesty made, he is my son; he was born to my Majesty. It is proper for a son to be an avenger of his father. Now, as for him who will lose it and will not fight over it, he is not my son; he was not born to me.

Curses of the protasis-apodosis variety also extended into the explicitly religious literature concerned with the afterlife, where even supernatural beings could be threatened. A representative example can be found in Coffin Text Spell 277 (c.2100 BCE), which offers protection to the deceased by singling out various potential wrongdoers for punishment:Footnote 34

ỉr nt̠r nb ỉr nt̠r.t nb.(t) ỉr ɜḫ nb ỉr mt nb mt.t nb.(t)

ns.wt rɜ=f ḫft=ỉ ḫr=f n šc.t ḥkɜ ỉmy n h̠t=ỉ

As for any god, as for any goddess, as for any spirit, as for any dead man or any dead woman, who will lick off his spell against me today, he shall fall to the execution blocks and the magic that is in my belly.

On the other hand, the same structural formula, albeit translated a little differently in English, could also be deployed just as effectively in healing contexts as those of punishment. It is standard in medical texts, as illustrated by this example from Papyrus Ebers (c.1550 BCE):Footnote 35

ỉr gm=k d̠bc sɜḥ r-pw mr=sn ph̠r mw ḥɜ=sn d̠w sty=sn ḳmɜ=sn sɜ d̠d.ḫr=k r=s mr ỉry=ỉ

If you find [lit. as for your finding] a finger or a toe and they are painful, and fluid circulates around them, and they smell bad and emit a worm, you should say: “a disease I must treat”.

The protasis-apodosis structure also entered the realm of Egyptian magical practice, enabling scribes to write down what the consequences caused by certain spells might be. A basic example is:Footnote 36

ỉr šnw.t rɜ pn r ḫfty nb n… ḫpr d̠w ỉm=f r hrw-7

If this conjuration of the mouth [is deployed] against any enemy of [name of whoever was being protected], badness will come to pass concerning him for seven days.

Thus, one can trace the protasis-apodosis structure across all manner of contexts. Such varied examples indicate that the stylistic aspect of regulating labour in the Horemheb and Nauri decrees of the New Kingdom is by no means novel: on the contrary, it is highly conventional, and fits into the broader Egyptian intellectual tradition of forming conditional clauses in settings ranging from justice and law enforcement to chthonic curses, protective magic, and medicine. Nevertheless, alongside the new concept of hp-law, there is one other highly significant modification: the deployment of harsh corporal punishment, the origin of which warrants additional investigation.

Corporal Punishment in the Horemheb and Nauri Decrees: Influence from Mesopotamia?

For the period before the Horemheb and Nauri decrees, there is no firm evidence of Egyptian labour being regulated by the threat of legally mandated corporal punishment. Indeed, while beatings were a common method of the ad hoc disciplining of subordinates by superiors as early as the Old Kingdom,Footnote 37 corporal punishment as a legal sanction is not even conclusively attested in any Egyptian context before the New Kingdom.Footnote 38 While such absence of evidence cannot be deemed conclusive evidence of absence, it is nonetheless striking given that there is no shortage whatsoever of evidence for corporal punishment in the period immediately following. Corporal punishment, in various forms, appears to have become prominent after the Hyksos occupation of the Egyptian delta (c.1650–1550 BCE), which is unlikely to be coincidental. Based on an analysis of personal names, it seems highly likely that the Hyksos were a Semitic-speaking people.Footnote 39 This is consistent with material culture finds that suggest an origin in the southern Levant.Footnote 40 If so, it is logical to postulate that their legal tradition was not dissimilar to that of other Semitic-speaking peoples, most notably that of Akkadian speakers. While it is important to note that the geographic distance between the original Hyksos heartland and the core of the Akkadian world, Mesopotamia, was considerable, it is widely accepted that the Akkadian influence on the scribal traditions, schools, and intellectual culture of territories to the west of Mesopotamia was significant.Footnote 41 In the Akkadian legal tradition, we find many instances of corporal punishment strikingly similar to those in the Nauri and Horemheb decrees. For example, in arguably the most famous Akkadian legal text, the Laws of Hammurabi (c.1810–1750 BCE), one may find the following clause (§282) providing a legal mandate for facial mutilation:Footnote 42

šumma wardum ana bēlišu ul bēlī atta iqtabi kīma warassu ukânšuma bēlšu uzunšu inakkis

If a slave has said to his lord: “you are not my lord”, when he has substantiated that he is his slave, his lord will sever his ear.

This is highly representative of the Hammurabi legal corpus as a whole, with other clauses granting similar legal justification for putting out eyes (§193, §196), breaking bones (§197), severing tongues (§192), breasts (§194), and hands (§195, §218, §226, §253), knocking out teeth (§200), whipping (§202), and impaling (§153).Footnote 43 This mutilatory tradition displayed considerable staying power, as Assyrian kings set out similar punitive provisions seven centuries later. For example, in Middle Assyrian Laws Tablet A (c.1100 BCE), the following provision is made:Footnote 44

A §4 šumma lu urdu lu amtu ina qāt aššat a’īle mimma imtaḫru ša urde u amte appēšunu uznēšunu unakkusu šurqa umallû a’īlu ša aššiti[šu] uznēša unakkas u šumma aššassu uššer [uz]nēša la unakkis ša urde u amte la unakkusuma šurqa la umallû

If either a male or female slave has received anything from the wife of a man, they will sever the nose and ears of the male or female slave. They will restore the stolen goods. The man [whose] wife it is shall sever her ears, and if he spares his wife (and) does not sever her [e]ars, they will not sever those of the male or female slave, (and) they will not restore the stolen goods.

There are many other examples of this sort in the text, including severing ears (§5, §24, §40, §44, §59), noses (§5, §15), fingers (§8, §9), genitalia (§15) and possibly breasts (§8), as well as various forms of beating (§57, §59), whipping (§44) and impalement (§53).Footnote 45 These sanctions are predominantly associated with theft and matters of domestic insubordination, and – both in the Assyrian examples above and in earlier legal documents from the Old Babylonian and Ur-III periods – it is striking that corporal punishment is generally reserved for slaves and other classes of unfree labourer.Footnote 46 Clearly, the topic of the Egyptian Horemheb and Nauri decrees is overall rather different, with these texts often being concerned with regulating and, if necessary, punishing relatively or even very senior officials. Still, the punishments themselves are nonetheless markedly similar and, in many cases, identical to their Mesopotamian counterparts. Bearing in mind that these decrees were published after the Hyksos period, when elements of Semitic law could conceivably have been imported into Egypt, a case can be made for influence from the Semitic legal tradition being directly present in the Egyptian decrees. This influence was clearly not a wholesale uptake, as the offenders targeted were a different social group. Instead, it appears that the Egyptians sought to mix and match, bringing in punishments from abroad to help regulate labour in line with the demands of their own socio-economic reality.

The case for such influence is strengthened further by the appearance of a substantial number of Semitic loanwords related to judicial administration, crime, and punishment in the Egyptian language, all of which date to the period after the Hyksos ascendancy. While many of these words occur only rarely or are only firmly attested after the New Kingdom, the number of items is nonetheless too large to ignore. Thus, this is, at the very least, explicit evidence of the uptake of judicial terminology, which – while it does not constitute categorical proof of an accompanying shift in legal practice – does make it appear highly likely. A summary of the key terms in question is given above (Table 1).

Table 1. Semitic loanwords connected to justice and related concepts appearing in the Egyptian language after Hyksos Rule (post-1550 BCE) and broadly coinciding with the rise of corporal punishment as a means of labour regulation in Egypt.

This table cannot be deemed satisfactory proof of post-Hyksos Egyptian justice evolving along Semitic lines, and even less that the administration of labour was evolving under an imported influence. However, what it does show is that – at least to a certain extent – the language of penal administration was becoming permeated with a Semitic lexicon, which may point to a degree of intellectual closeness which, in turn, manifests itself in the growing tendency towards corporal punishment as a judicial sanction. As has been shown, the latter is of considerable importance to Egyptian labour management specifically.

It should also be noted that such emerging intellectual proximity between Semitic and Egyptian traditions of the later second millennium BCE already has known parallels in other fields of written culture. For instance, in the domain of divination, it has been illustrated that lecanomancy – a highly technical mantic practice originating in the Mesopotamian Old Babylonian Period (2000–1600 BCE), which generated omens by observing oil patterns on water – was adopted by the Egyptians in the New Kingdom.Footnote 48 Similarly, the typically Mesopotamian genre of disputation literature – stories involving verbal superiority contests between various living things or inanimate objects, attested there from the third millennium BCE – appears in Egypt for the first time and in multiple attestations during the New Kingdom.Footnote 49 Meanwhile, Semitic religious traditions from the Levant also percolated into Egypt, with quintessentially Levantine deities such as Anat, Ba'al, Qudshu, Astarte, and Reshep all appearing in the Egyptian written record at a time roughly contemporaneous to the Nauri and Horemheb decrees.Footnote 50 The evidence for such a wide range of influences from the Semitic world is further enhanced by archaeological findings of cuneiform Akkadian texts at New Kingdom sites, most notably the famous Tell el-Amarna cuneiform archive, which contains documents ranging from royal letters to mythological compositions.Footnote 51 In such a context, a degree of Semitic influence – emanating from Mesopotamia and its surrounding polities – seems entirely logical in the field of punitive and labour administration within New Kingdom Egypt. Indeed, it would be somewhat strange for such an influence to be absent, given its prominence in so many other textual genres of the period.

Conclusion

Labour regulation in the Nauri and Horemheb decrees relies on a mixture of native Egyptian and imported Semitic features, most likely associated with the Hyksos presence in Egypt and the continued links with Levantine and Mesopotamian intellectual culture thereafter. The phrasing of the decrees is characteristically Egyptian, and there is precedent for pharaohs issuing decrees in this style going back to the Old Kingdom an entire millennium earlier. However, the allusions to a broader concept of law (hp) – as opposed to just ad hoc provisions – and the provision of tough corporal punishments are new, both for Egyptian justice in general and for Egyptian labour regulation more specifically. While the new conceptualization of law (hp) might conceivably be an Egyptian innovation, the new punishments almost certainly point to some degree of foreign influence, especially given the extent of contact with the linguistic, religious, and broader intellectual traditions of Mesopotamia and the Levant at the time. However, it is interesting to note that the way these punishments are deployed is distinctly Egyptian. Unlike the Mesopotamian setting, they are not limited to slaves and other unfree labourers but can instead target high officials.

The underlying reasons for these changes most likely cannot be limited solely to an organic phenomenon of cultural assimilation based on the historical reality of contact between Egypt and the Semitic world. While such an unplanned diffusion of concepts may have played a part, with the fluid transmission of intellectual culture contributing to the hybrid nature of the legal changes, it is nonetheless probable that the uptake of foreign ideas into the sphere of Egyptian law and labour regulation was largely a deliberate decision. Such a choice would have been linked to efforts to further cement royal power at a crucial time: on the one hand, this was a phase when New Kingdom Egypt was nearing its greatest territorial extent, and a period when the crown of Egypt as an institution was arguably politically and militarily stronger than at any other point in its entire ancient history; on the other hand, this time also saw dynastic weakness and legitimacy crises, which could cast doubt on any given holder of the crown. By regulating labour through hp – imposed top-down from the pharaonic government – agency in interpreting vague regulations (and hence potential for abuse of power) was being stripped away from provincial officials (whom the royal decrees see as their main adversaries). The crown was saying exactly what had to be done, thereby transferring agency to itself, and it now had a specific term for it. Brutal penalties, borrowed from a foreign tradition that had assimilated into Egyptian legal culture, reinforced the point even further, presumably in the hope of attaining higher productivity as a result, and possibly with the additional aim of scaring other would-be offenders, including relatively high-ranking ones, into compliance. Given the vast infrastructural outputs of the New Kingdom, as evidenced by the many flamboyant and vastly labour-intensive pharaonic building projects emblematic of the period, it appears that, at least for several centuries, this strategy was not without success. In turn, these infrastructural outputs allowed the crown to materialize its power further, presenting itself as a force capable of dominating the land through monumentalism. Thus, the pharaoh could take physical action to shape both his country and the bodies of those who worked in it – or, rather, those who did not work to a required standard and therefore deserved mutilation or beating.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Master and Fellows of Christ's College, Cambridge, for generously providing financial backing for this work through the Lady Wallis Budge Fund. Funding was also gratefully received from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (project reference AH/V006711/1). Additional thanks are due to the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, and the HSE University Institute for Oriental and Classical Studies, Moscow, for providing supportive research environments during the unprecedented challenges of the global Covid-19 pandemic.