INTRODUCTION

In the global history of sugar, early modern plantations are widely held to be a product of the expansion of the European capitalist system into the Atlantic World. An important paradigm suggests the following: the plantation method of sugar production emerged during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries alongside the expansion of European sugar frontiers across the Atlantic Ocean. A “sugar revolution” in the Caribbean around the time of the mid-seventeenth century created a highly exploitative, slave-driven capitalist agro-industry, which then experienced transformations from the end of the eighteenth century amid the Haitian Revolution and prompted by the Abolitionist Movement. The system eventually spread to the rest of the world during the nineteenth century.Footnote 1

However, that linear narrative marginalizes the early modern sugar plantations that existed outside the Atlantic World. Researchers of Southeast Asia have become increasingly aware that nineteenth-century sugar plantations in Indonesia and the Philippines were not only influenced by the “Atlantic” model, but also deeply enmeshed in local agricultural traditions.Footnote 2 Moreover, local traditions were not isolated and unchanging but interacted with an often-ignored expansion of Chinese sugar production during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Almost contemporaneously with the rise of the slave-driven sugar economy in the Caribbean, the Chinese took with them overseas their own package of sugar-making technologies, which had originally been developed in South China in the early seventeenth century. Those techniques then found their way to many locations in Southeast Asia, such as Siam (Thailand), Cochin-China (central and southern Vietnam), the Philippines, the north coast of Java, and Bengkulu (South Sumatra).Footnote 3 That expansion engendered various sugar plantations as they adapted to local circumstances.

It is regrettable that the history of early modern Southeast Asian sugar plantations and their use of Chinese technology has been insufficiently studied. In most cases, our knowledge is limited by a shortage of local archives, which leaves us unable to go beyond general questions such as their locations, sizes, and when precisely they were in operation. In that regard, the sugar plantations in rural Batavia (Jakarta) are an exceptional case, for they are well documented in rural archives generated by the Dutch United East India Company (the VOC) in Batavia. All the same, a deep study of these archives is wanting, with current scholarship in the field limited to a few general works, some of which are only tangentially related. For instance, the mid-seventeenth-century origin of Batavian sugar is discussed as the background to Chinese economic ascendency;Footnote 4 the mid-eighteenth-century crisis in Batavian sugar production is debated as an origin of the Chinese Massacre in 1740;Footnote 5 the late eighteenth-century transition of Batavian sugar production is presented and studied either as an expansion of a cross-border economy between Banten and Batavia, or as a precursor to the modernization of Javan sugar production in the early nineteenth century.Footnote 6 Further, Hendrik E. Niemeijer's definitive monograph on seventeenth-century Batavia and Bondan Kanumoyoso's dissertation on early modern rural Batavia each shed important light on the development of Batavia's sugar economy from the mid-seventeenth until the early eighteenth centuries. However, because sugar is dealt with only rather generally in their book-length works, neither engages critically with the subject.Footnote 7

This article aims to approach Batavia's sugar plantations from a micro-spatial perspective through archival work on a “perfect map” (perfecte caarte)Footnote 8 that belonged to a widowed Chinese sugar entrepreneur named Tan Hiamtse (?–1722).Footnote 9 The map was granted to Hiamtse on 19 May 1685 by the Dutch rural council of Batavia (College of Heemraden) and refers to an extensive plot of land encompassing a number of sugar plantations.Footnote 10 That decision was made at a critical stage while a major expansion of sugar production in Batavia was taking place, so that control of plantation space was therefore both highly desirable and contested. It should be no surprise, then, that a series of debates and surveys about the nature of landownership in rural Batavia soon began to revolve around Hiamtse's “perfect map”. Those debates reveal a colonial rural society that featured encounters between people and ideas from all across the early modern world. There were Chinese entrepreneurs who introduced sugar-making techniques from South China, JavaneseFootnote 11 labourers whose presence had originated from the expansion of the Mataram Empire in western Java, and Dutch colonial elites who imposed on the plantations of the tropics the landowning culture from the polders of the Low Countries.

Focusing on their interactions on the ground, this article aims to elaborate a basic question: How did a sugar plantation society take shape in a rural colonial space in early modern Southeast Asia? This article will first contextualize the significance of Hiamtse's perfect map in the sugar economy and rural administration of late seventeenth-century Batavia in order to understand how it gave rise to a distinctive plantation space. We shall then proceed to look at Hiamtse's Javanese neighbours, showing how Hiamtse's perfect map encroached on the land rights of a disenfranchised Javanese rural society around Batavia. By the end, we will have examined how a plantation labour regime grew from that disenfranchised rural society.

THE WIDOW HIAMTSE

Who was Hiamtse? And how, as a widow, did she become a sugar entrepreneur? In the document that mentions her “perfect map” she is recorded as “Njai Tan Hiamtse, widow and estate executor (boedelhouster) of the late Chinese Lieutenant Li Tsoeko”.Footnote 12 Whereas her title, “Njai” (nyai, nga), indicates that she was probably a Peranakan or even an indigenous woman, her Chinese surname, Tan (likely Chen 陳 in Mandarin), was different from her husband's surname Li (李), indicating that she already had a Chinese identity before marrying Tsoeko, either because her father was a Tan-surnamed Chinese, or because she had previously been adopted by a Tan-surnamed Chinese family.Footnote 13

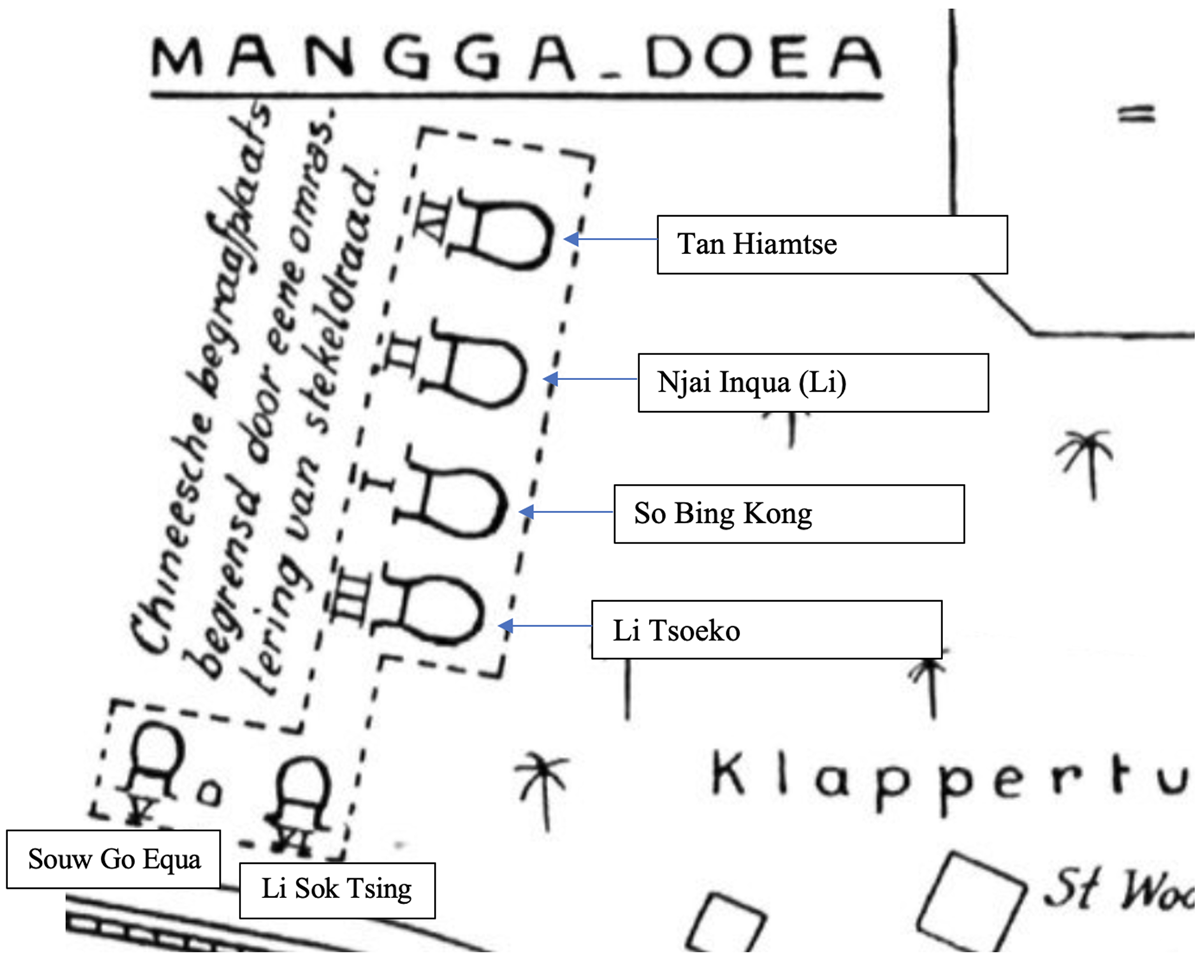

One advantage for Hiamtse as a woman entrepreneur with a Chinese identity in early modern Batavia was that her status enabled her simultaneously to manage business within a Southeast Asian milieu, where there was “a common pattern of relatively high female autonomy and economic importance”,Footnote 14 and within an elite Chinese circle in Batavia, which controlled enormous wealth.Footnote 15 An important material testimony to her social and family background was a graveyard, previously standing in the northern part of the centre of Jakarta, containing key members of two allied elite Chinese families.Footnote 16 In the 1920s, the Dutch Sinologist, B. Hoetink, drew a plan of it as follows (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The family graveyard of Tan Hiamtse.

Adapted from Hoetink, “So Bing Kong: Het eerste hoofd der Chineezen te Batavia (Eene nalezing)”, illustration between pages 40 and 41.

The two graves placed centrally, in the middle of the vertical row, held the remains of So Bing Kong (Su Minggang 蘇鳴崗, c.1580–1644, also known as Bencon) (Grave I), the first Chinese Captain of Batavia, and his wife Njai Inqua (Li Qinci 李勤慈, ?–1666/1667) (Grave II). The two graves on each side of them belonged to Li Tsoeko (Li Zuge 李祖哥 or Li Jiongcui 李烱萃, ?–1680/1681) (Grave III) and Tan Hiamtse (Tan Tsing Ie 陳?, ?–1722) (Grave IV). The two horizontally arranged graves belonged to their coupled offspring, namely Souw Go Equa (Su Zhongzheng 蘇中正, 1650?–1708) (Grave V), who was So Bing Kong's grandson, and Li Sok Tsing (Li Shuzhen 李漱貞, ?–1684) (Grave VI), who was Tsoeko and Hiamtse's daughter.Footnote 17

The founder of this familial union was Njai Inqua, who was also a wealthy female proprietor. Njai Inqua was married twice and widowed twice. After her first husband So Bing Kong died, in 1644, she married another wealthy Chinese merchant in Batavia, Conjock (?–c.1661).Footnote 18 Conjock died, too, in 1661,Footnote 19 but the now twice-widowed Njai Inqua lived for another few years. Shortly before her own death,Footnote 20 in 1666, Njai Inqua decided to entrust her property to Tsoeko and Hiamtse's family. She nominated the still teenaged Souw Go Equa – grandson of So Bing Kong – as her universal heir and pre-arranged a marriage between him and Li Sok Tsing, who was Tsoeko and Hiamtse's daughter. To secure their union, Njai Inqua appointed Hiamtse's husband Tsoeko executor of her estate (Figure 2).Footnote 21 As a result of this arrangement, much of the wealth from Njai Inqua and her two marriages was subject to Tsoeko's administration.

Figure 2. A familial alliance.

Njai Inqua's arrangement ultimately “benefited” Hiamtse in a rather tragic way, because of the early death of Tsoeko in 1680/1681. Tsoeko's death was a testimony to the chaotic and violent origin of Batavia's sugar frontier, which came about amid a mid-seventeenth-century global sugar crisis. From the 1630s–1650s, the Dutch West India Company (the WIC) invaded Brazil, which was then the principal sugar production area in the Atlantic World. The WIC's action caused a great disturbance to the global sugar trade, and, in response to the crisis, new sugar frontiers emerged in the Caribbean, on the north-eastern coast of South America (the “Wild Coast”), and in Asia.Footnote 22 In the mid-1630s, the English East India Company (the EIC) approached a number of Chinese entrepreneurs and contracted them to produce sugar in Banten, to the west of Batavia.Footnote 23 The VOC soon followed suit, supporting the Chinese in Batavia to turn part of the area around the city (the so-called Ommelanden) into plantation space from the end of the 1630s.Footnote 24

In the early stages, this nascent plantation space was fraught with violence and disorder, as it was situated on a battlefield between the Banten sultanate and the VOC.Footnote 25 In the late 1650s and the early 1680s, Bantenese armies pillaged Batavia's sugar plantations. The most disastrous among these conflicts was the invasion of 1656–1659, during which all the sugar plantations that lay outside the defensive line of Batavia were ruined. In 1662, the Company even developed a plan to replace the Chinese method of sugar production, which used buffalo-driven mills and tended to expand into the hinterland, with a water-driven sugar mill that was to be situated within the defence line and operated by a European entrepreneur.Footnote 26 That plan failed to materialize, and, as we will see from Hiamtse's case, Chinese sugar entrepreneurs expanded once again into the dangerous frontier region in the 1660s and 1670s.

The Company, moreover, contributed to new confusion by issuing varying types of documents to those who were willing to populate this frontier, either to turn it into cultivated fields, or to build a buffer zone between Batavia and its enemies. A notice of 9 December 1678 shows land documents issued by the Company for rural Batavia included title letters (erfbrieven), land letters (grontbrieven), donation letters (donatie brieven), purchase letters (coopbrieven), maps (kaarten), or “whatever could be identified” (hoedanigh die genaemt mochten zijn). The Company kept no centralized cadastral registry for such documents and the practice led to a complex variety of landholding practices.Footnote 27

Despite the violence and chaos, Hiamtse's husband Tsoeko belonged to a small group of adventurous Chinese, who, against the odds, attempted to open up a sugar frontier. Tsoeko himself established his sugar enterprise on some ruined plantations previously belonging to Bingam (Pan Mingyan, 潘明岩, ?–1663). As the Chinese Captain of Batavia from 1645–1663,Footnote 28 Bingam was among the first generation of Chinese sugar entrepreneurs in Batavia, and, by 1643, he had “planted many fields with sugar canes”.Footnote 29 In 1650, Bingam acquired the land of Tanah Abang from the Company to use for setting up sugar mills.Footnote 30 To connect the new property with Batavia City, he had already obtained permission from the Company in 1648 to dig a canal, which would be named after him, as the “Bingam Canal”.Footnote 31 However, Bingam's investments were to collapse into disaster when the war between Banten and the VOC broke out in 1656, for his plantations lay outside the defence line of the VOC and were destroyed by the Bantenese force.Footnote 32

After Bingam's death (1663), in 1664, his son Towasia transferred Bingam's land to the then Chinese boedelmeester (Estate Manager), Tsoeko, and another Chinese for just 440 rijksdaalders.Footnote 33 In 1666, Tsoeko asked the Company to prohibit unauthorized transport along a canal (most likely the Bingam Canal), in order to reserve it for the purpose of shipping firewood to his sugar mills on the land previously owned by Bingam.Footnote 34 In 1668, Tsoeko obtained his partner's share and became the sole owner of this land.Footnote 35 In 1679, Tsoeko further applied to acquire extra land near Fort Angke (Ankee) for his sugar plantations, which the Company acknowledged were “among the most prominent of this city”. The Company approved Tsoeko's request but was reluctant to issue a new title letter.Footnote 36 This request indicates that, by the end of the 1670s, Tsoeko had greatly expanded his operations westwards from the late Bingam's base in Tanah Abang to the Angke River (Figure 3).

Figure 3. From Tanah Abang to Angke River.

Adapted from a cadastral map of c.1706, NA, Verzameling Buitenlandse Kaarten Leupe, VEL. 1185.

Tsoeko's expansion exposed him to grave danger. The area to the west stretching from the Grogol River to the Angke River was claimed by other landholders and directly faced Tangerang, which was then contested by Banten. It was in an armed skirmish with an invading Bantenese force towards the end of 1680 that Tsoeko lost his life.Footnote 37 Tsoeko's death left the entire sugar enterprise in the hands of his wife, Hiamtse, albeit now only the eastern tract between Tanah Abang and the Grogol River was still under their control. The vast area of land between the Grogol River and the Angke River was by then being contested by others.Footnote 38

PERFECT MAPS

Facing these rural administration problems, the High Government of the VOC in Batavia planned to solve them by introducing a typical Dutch rural institution. On 19 September 1664, the decision was taken to install a College of Heemraden, “in accordance with the mode customary in our fatherland”.Footnote 39 With its origins in the polder areas of the Low Countries, heemraden was originally the term for members of a water board (waterschap), but then, around the thirteenth century, certain regional water boards (hoogheemraadschap) began to assume administrative functions in the Dutch polder society, whereupon the heemraden began to evolve into a sort of rural government.Footnote 40 By the seventeenth century, the idea of rural administration through heemraden had become so deeply ingrained that a transfer to a tropical colonial area with hardly any polder seemed entirely reasonable to the Dutch colonial elites sitting in the Castle of Batavia.

This early College of Heemraden, however, left no archive and, in the 1670s, its function was absorbed by the College of Schepenen. A new College of Heemraden was established by the High Government on 13 October 1679, originally with the aim of raising funds to dig a “ring-ditch” (ringsloot) protecting the most valuable part of rural Batavia,Footnote 41 and then with further powers added on 23 July 1680 to take charge of the rural administration of Batavia.Footnote 42 On 21 November 1680, the Company made a division of responsibilities between two land surveyors, one who would specialize in measuring the land within the city of Batavia, and the other outside it.Footnote 43 In 1681, there had already been a land surveyor serving the College of Heemraden.Footnote 44 On 26 September 1684, the College was further reorganized and began to assume a proactive role in the rural administration.Footnote 45 On 23 October 1685, the Company specified that all rural land transactions had to be registered by the College.Footnote 46

This “typical Dutch” rural institution offered Hiamtse a legal path to securing and advancing her late husband's sugar enterprise. To expedite it, she learned to use the maps drawn up by the Dutch land surveyors within the Dutch colonial land system. Even before its approval by the College of Heemraden on 19 May 1685, Hiamtse had already asked an important Dutch surveyor, Jacob Verberkmoes (Verbergmoes), to survey her land and draw up a map of it.Footnote 47 However, Verberkmoes came up with a map covering only the eastern part of her land, because he was unwilling to venture to the western part, on the pretext that “it is not accessible”.Footnote 48 Hiamtse subsequently applied to the reformed College of Heemraden. The College decided to let its surveyor measure this land and from the findings make a “new, perfect map” for Hiamtse.Footnote 49

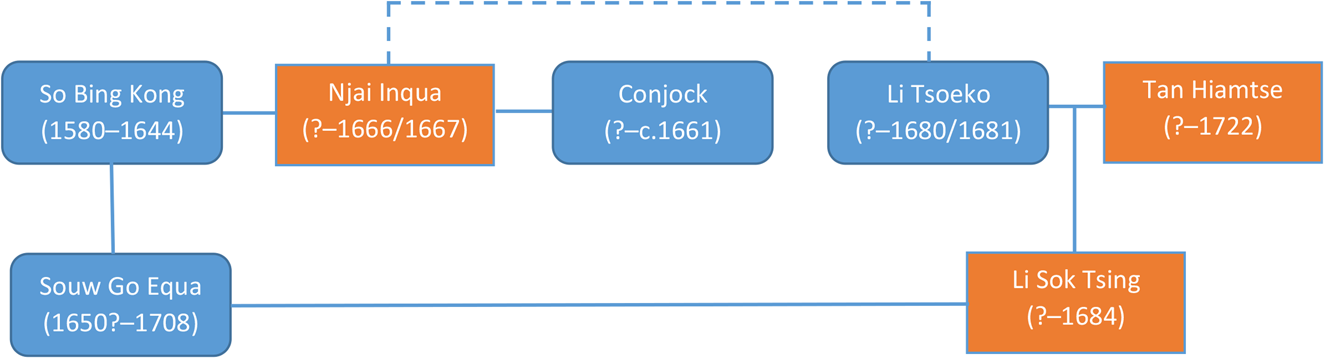

The concept of the “perfect map” stemmed from early modern Dutch land culture.Footnote 50 It saw its zenith in the large-scale drainage projects carried out in early seventeenth-century northern Holland, such as the impoldering of the Beemster (drained in 1612), which took place after a group of Amsterdam merchants, including two of the founders of the VOC, decided to transform the former Beemster Lake into a polder.Footnote 51 Comprehensive cadastral maps drawn up by land surveyors, known as “perfect maps”, featured prominently in the project from the outset, there being a printed map showing “the situation of Beemster, […] put on perfect (comprehensive) scale by Pieter Cornelisz. Cort of Alkmaar, sworn land surveyor, 1607” (Figure 4). Its cartouche depicts the surveyor carrying an astrolabe, implying a certain accuracy derived from the application of triangulation technology.Footnote 52 Thereafter, the lake was remeasured in 1611, leading to another perfect map (perfecte caerte).Footnote 53

Figure 4. Detail showing the land surveyor Pieter Cornelisz. Cort measuring the Beemster in 1607.

NA, 4.VTH, 2598.

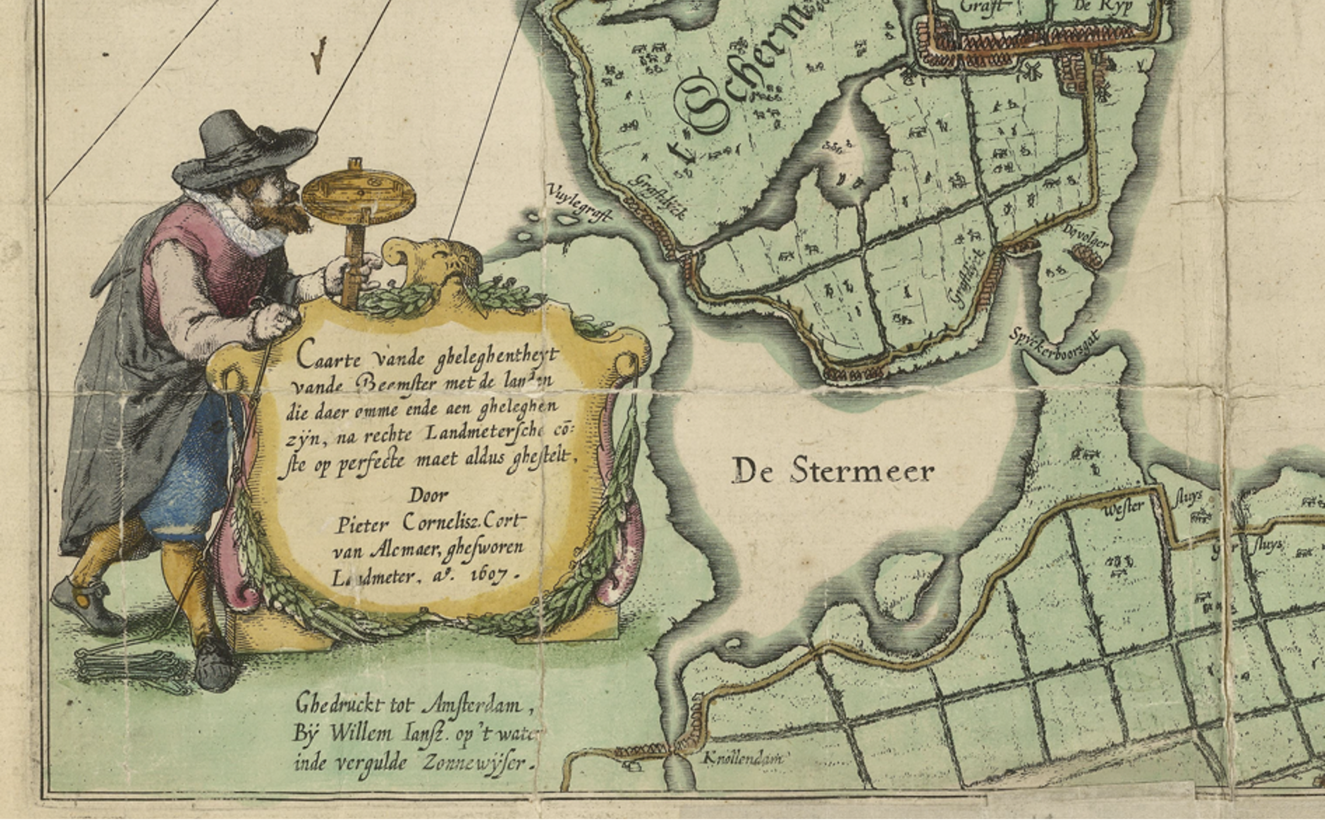

From polders to plantations, cadastral maps measured by European surveyors were recognized by the Company as primary evidence in the solving of land disputes like Hiamtse's. After an onsite measurement, the College's land surveyor, Ewout Verhagen, returned on 2 June 1685 with a map that showed a confused situation. The Company had initially ascribed an immense plot of land to Bingam in 1650, land that, as mentioned, was sold in 1664 to Tsoeko. Notwithstanding its grant of the land, the Company continuously made new allocations of land in the same area, which had the effect of creating many overlapping land claims. In order to honour the first donation letter (donatie brief) issued by the Company to Bingam in 1650, the College initially decided to make the above “perfect map” for Hiamtse and eliminate all overlapping claims.Footnote 54

The College's order still needed to be adapted on the ground. Right at the start, with its decision of 2 June 1685, the College had allowed the heirs of the late Balinese Captain, Mangus, to keep a plot of land in return for payment of compensation. Captain Mangus's family had been settled there for many years and had set up a sugar mill at great expense, and all their land lay within the boundary of the land claimed by Hiamtse. To avoid further disputes, therefore, the College decided to draw up a “perfect map” for them, too,Footnote 55 and further border adjustments followed. For instance, the land of the widow of Willem de Rover encroached on Hiamtse's land to the extent of 250 roeden.Footnote 56 Initially, the College decided that De Rover's land should be returned to Hiamtse, but on learning that De Rover's widow had already rented it to a Chinese sugar entrepreneur whose mill stood squarely on the disputed land, the College agreed to allow the Widow de Rover to retain the disputed land. Hiamtse would then receive compensation from elsewhere, although, as we shall see, that was to cause further problems.Footnote 57 As a result of the surveys and adjustments, this part of rural Batavia came to be clearly measured and registered in a cadastral map (Figure 5) of approximately 1706, which showed no further overlapping claims.

Figure 5. The contested land between Hiamtse (Njai Tsoeko), the heirs of the late Balinese Captain Mangus, and the widow of Willem de Rover.

Adapted from a cadastral map of c.1706, NA, Verzameling Buitenlandse Kaarten Leupe, VEL. 1185.

We can see from these disputes that Hiamtse was not the only sugar entrepreneur in the area. Her neighbours, too, were investing in sugar plantations, indicating that, although war-torn, this area was also becoming contested plantation space. The change was associated with the colonial expansion of the VOC in the early 1680s. Shortly after Tsoeko died, the VOC launched a military expedition against Banten, and in 1684 signed a treaty with Banten to annex Tangerang and make the Cisadane River the new border.Footnote 58 That action ended a decades-long military threat from Banten, and, also in the early 1680s, the Company sought to protect Batavian sugar from competition by imposing treaties on Banten and the Mataram to restrict sugar production in their territories.Footnote 59 These treaties ensured a strong demand for Batavian sugar, for other sugar production areas on the north coast of Java could no longer pose serious competition.

The favourable conditions induced a sugar boom. In 1696, the College of Heemraden surveyed all sugar mills in rural Batavia, revealing that there were 116 mills owned by ninety-four sugar entrepreneurs, of whom seventy-six were Chinese, five Europeans, five Mardijkers, and eight of undisclosed ethnicity. Most of the mills were new, seventy-seven of the 116 having been constructed fewer than five years earlier and eighteen mills between six and ten years before. Besides four mills of unspecified age, only seventeen were older than ten years, indicating that growth of the sugar economy, which had begun in the mid-1680s, accelerated greatly from about 1690.Footnote 60

Hiamtse, as one of the most firmly established sugar plantation owners, owned seven sugar mills. She herself operated five older mills, which had been standing for between twenty-four and thirty years, while her son (Li Gieko) operated a newer mill, which had been standing only three years. Another mill, also three years old, was rented to another Chinese.Footnote 61 About ten years later, the cadastral map of c.1706 shows that Hiamtse had further expanded her interests, for she and her children now held three large pieces of adjacent land along the Angke River downstream of their existing holding, their new property likely forming a new sugar frontier. Together with that of another important Chinese sugar entrepreneur, Li Tsionqua (Li Tsionco), Hiamtse's name also appears on two pieces of land along the Mookervaart Canal – constructed in the 1680s to connect Batavia City with an emerging sugar frontier in the recently annexed Tangerang region.Footnote 62

However, having joined the sugar boom only recently and operating sugar mills most of which stood on rented land, the majority of Chinese millers were less well established than Hiamtse. Their economic practice of renting land for setting up sugar plantations opened the door to certain high-ranking Dutch officials to become rentiers. The most notable among them was Joan van Hoorn, who presided over the reformed College of Heemraden from 1684–1687 and was therefore a major policymaker in the mid-1680s reorganization of Batavia's rural administration that dealt with Hiamtse's case.Footnote 63 Afterwards, Van Hoorn became the Director General of the VOC in 1691 and Governor General from 1704 to 1709.Footnote 64 According to the survey of 1696, Van Hoorn owned seven plots of land, which he rented to eight Chinese sugar entrepreneurs, who, within seven years, had constructed eleven sugar mills there.Footnote 65 Making use of his privileges, Van Hoorn continued to exploit the sugar boom right up to the end of his career. On 7 May 1709, just a few months before he retired to the Netherlands, he obtained a huge plot of land (c.2,790 morgens Footnote 66) in Tangerang, on which he was allowed to set up two sugar mills.Footnote 67 Within a few months, he had divided his new land into three pieces and sold each of them to Chinese buyers for a total of 10,690 rijksdaalders.Footnote 68

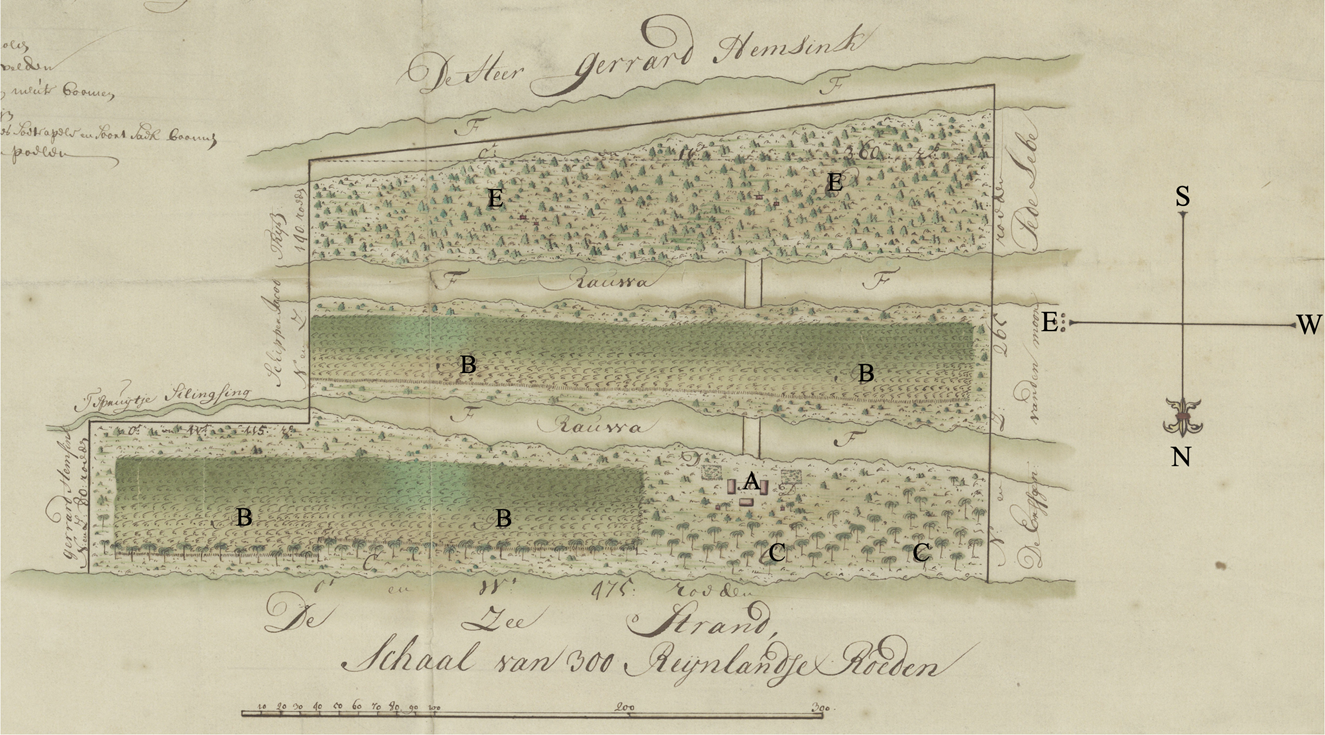

Moreover, the College of Heemraden also owned sugar plantations on behalf of the Company and rented them to Chinese entrepreneurs. The emergence of that type of landholding practice was linked to the “rebellion” of the Ambonese Captain Manipa Sanweru (Kapitein Jonker) in 1689.Footnote 69 The Company promptly killed Manipa Sanweru and confiscated his land, including a sugar plantation already constructed by some Chinese.Footnote 70 To ensure the ecological sustainability of the plantation, the Company added eight clauses stipulating a new rental contract, which included obligations to maintain land fertility and to replant firewood.Footnote 71 A plan drawn by a land surveyor of the College of Heemraden in 1732 comprehensively illustrates how the plantation was laid out (Figure 6). There was a sugar mill in the centre (Letter A) with two small cottages next to it. To the north-west, towards the sea, there was a small forest offering firewood (Letter C), while to the east and south of the sugar mill lay two long tracts of sugar cane field (Letter B). An orchard grew further to the south (Letter E), which was dotted with scattered cottages. With no paddy fields or any sizeable villages, this map represents a typical plantation space, lacking rural settlers but highly specialized in cash-crop production.

Figure 6. Detail showing a sugar plantation near Tanjung Priok (1732).

Adapted from NA, Verzameling Buitenlandse Kaarten Leupe, VEL. 1240.

DISENFRANCHISED JAVANESE

However, the comprehensively mapped plantations took up only part of Batavia's rural space. Surrounding them were many Javanese villages, but, with inferior land rights, they were vulnerable to the reformed colonial land system.Footnote 72 In Hiamtse's case, to the west of her plantations there was a Javanese settlement headed by Naija Gattij, who had been given a lease letter (leenbrief) by the Company in 1675 allowing him and his followers to settle there. Gattij's letter, however, failed to offer security, such as in early 1686 when the College of Heemraden was looking for compensation for Hiamtse's loss in the above-mentioned dispute with the widow of Willem de Rover. In that instance, the College decided to expropriate part of the land belonging to Naija Gattij and his followers and donate it to Hiamtse.Footnote 73

That event quickly alerted the Javanese community. On 16 April 1686, Naija Gattij appealed to the College of Heemraden, requesting a document more powerful than his lease letter of 1675, or at least as powerful as Hiamtse's landholding document.Footnote 74 On the same day, another Javanese neighbour of Hiamtse, Captain Soeta Wangsa, made a similar request for a piece of land occupied by his people.Footnote 75 The two requests presented the College with a dilemma. Both Naija Gattij and Soeta Wangsa had been allies of the VOC in the recently concluded war against Banten. Their settlements were on the front line and they had participated actively in the Tangerang Campaign in 1682.Footnote 76 However, an upgrade of their landholding documents would encourage all other Javanese commanders to follow their example and lead to a fundamental challenge to the landholding system of rural Batavia.Footnote 77 The College therefore submitted the case to the High Government of the Company in Batavia.Footnote 78

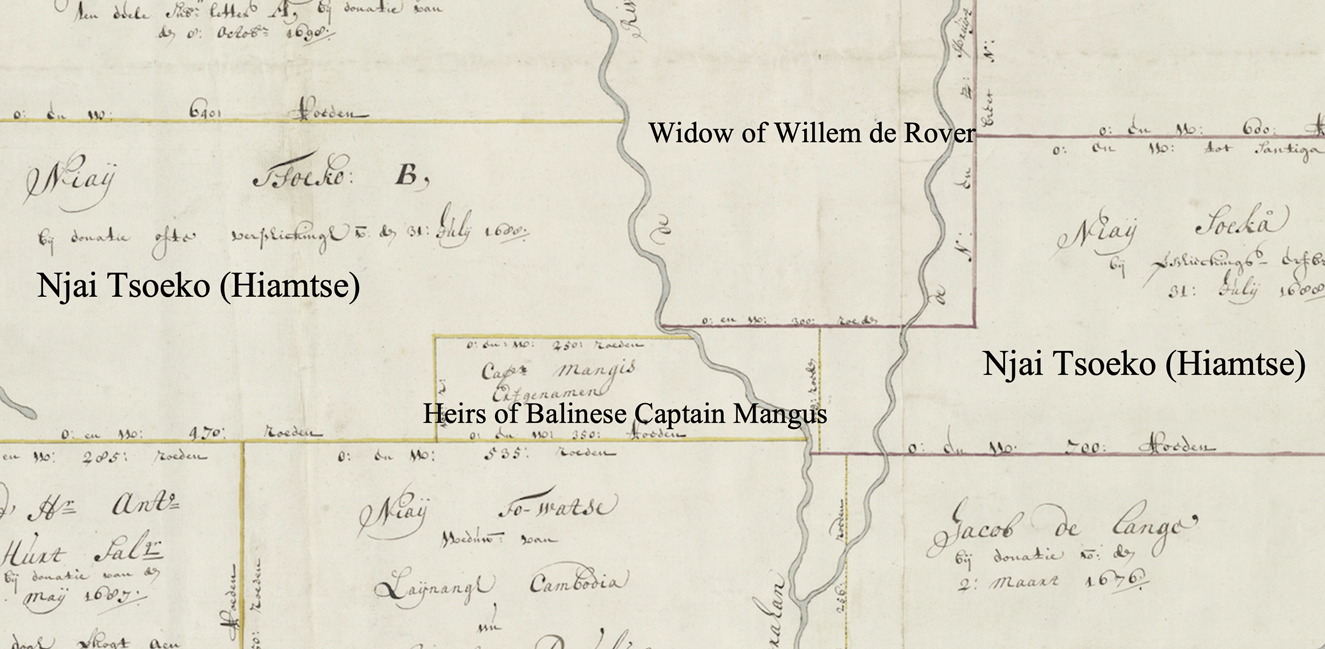

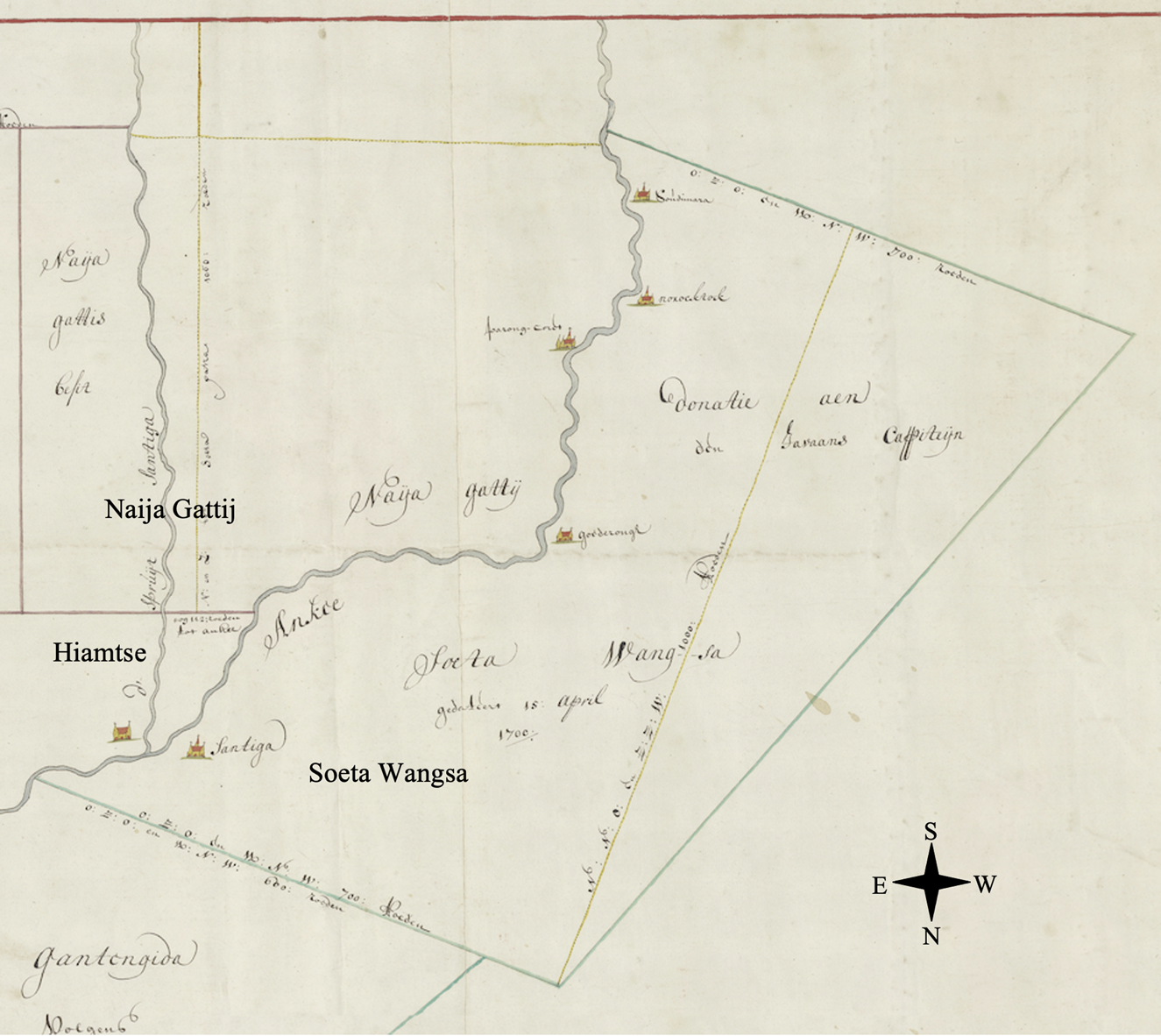

The High Government's response is intriguing. Approximately two months after the petition, on 18 June 1686, it decided to “qualify gentlemen Heemraden, according to findings, to give Javanese and some other indigenous people (inlanderen) some pieces of land in possession (besit), in order to properly cultivate it under the current conditions”.Footnote 79 Their seemingly positive reply in fact reinforced an old distinction between donated land or freehold on the one hand and “possessed” land or leasehold on the other, because the High Government merely agreed to give land into their “possession” (besit). The term “possession” (besit) gives an impression of full landownership, but in the context of early modern rural Batavia its meaning was closer to occupation (bezetting) or leasehold, for a possessor had no permanent landownership but merely occupied their land and had to pay tithes to the Company, which held ultimate ownership of the land and could revoke the possessory right. We should bear in mind that Naija Gattij and his followers lost part of their land to Hiamtse precisely because their land had the legal status of “being possessed” (wordt bezeten), while Hiamtse's land was registered as donated.Footnote 80 From the c.1706 cadastral map of rural Batavia (Figure 7), we can see that Naija Gattij eventually failed to obtain a donation letter as the land was still registered as “Naija Gattis besit” (in Naija Gattij's possession). Soeta Wangsa, too, failed in his petition of 1686, although he would later be rewarded with a donation letter, in 1700, for his good service to the Company.Footnote 81

Figure 7. The land of Naija Gattij, Soeta Wangsa, and Hiamtse.

Adapted from a cadastral map of c.1706, NA, Verzameling Buitenlandse Kaarten Leupe, VEL. 1185.

In spite of its reluctance to grant freehold ownership of land to Javanese commanders like Naija Gattij and Soeta Wangsa, the Company was meanwhile content to entrust them with authority over the rural Javanese population, authority that was linked to land tax. A crucial difference in rural Batavia between possessed land and donated land was that occupants of the former had to pay ten per cent of their agricultural output in tax while the latter was tax-free. As most Javanese rural dwellers lived on possessed land, they had to pay the tithe tax. All the same, the Company could not afford the enormous cost of dispatching its own personnel to collect such a relatively small tax from each Javanese household, many of which were in remote villages on the fringe of rural Batavia. The Company therefore relied on Javanese headmen to collect the tithes.Footnote 82 To make the system more efficient, on 12 March 1689, the College of Heemraden appointed two leading Javanese captains as chief collectors, namely Carsa for the east part of rural Batavia and Naija Gattij for the west, simultaneously authorizing them to nominate sub-collectors from the lower echelons of Javanese commanders.Footnote 83 On 2 April 1694, Soeta Wangsa replaced Carsa as the Javanese Captain accountable for the eastern tithes,Footnote 84 with the result that Hiamtse's two disenfranchised Javanese neighbours became the chief commanders of the entire Javanese community in rural Batavia.

The Javanese rural population they commanded was of very different origin from the highly commercialized Chinese community in Batavia. The diary of the Castle of Batavia shows that Captain Naija Gattij was from “Mataram” and Captain Soeta Wangsa was from “Pattij” (Pati), indicating that they were both originally from central or eastern Java.Footnote 85 The existence of these Javanese communities in rural Batavia was related to the expansion of the Mataram Empire onto formerly Sundanese land on western Java. After repeated failures in the wars targeting Banten and Batavia in the late 1620s, the Mataram ruler Sultan Agung (r. 1613–1645) launched a major campaign against his former Sundanese ally in the hinterland of Batavia in 1632, who, by then, had deserted and rebelled against the Mataram.Footnote 86 That campaign caused further depopulation of an already underpopulated region. Sultan Agung then sent immigrants from central and eastern Java to the region, and his successor Amangkurat I (r. 1645–1677) continued the policy.Footnote 87 A Javanese colony in Karawang, which was situated close to the east of Batavia, therefore expanded during the 1650s.Footnote 88 Amid this westward expansion of the Mataram Empire, many Javanese and Sundanese moved further into rural Batavia. The Company referred to them generally as “Javanese”, appointed commanders among them, and settled them as peasants in the hinterland, mainly to cultivate the rice that was in great demand by the urban population of Batavia and, occasionally, to be mobilized for military service.Footnote 89

These factors created a “Javanese” rural society consisting of many villages on the peripheries of rural Batavia, led by their own headmen, some of whom also served as military commanders for the Company and therefore held military titles.Footnote 90 Their settlement pattern can be identified with a specific section on the cadastral map of c.1706. It shows that the Company divided the land between the Small Cakung River and the Sunter River into many parcels, each corresponding to a Javanese settlement (Figure 8). Their land registry follows a standard format, such as “The honourable Company's (land) possessed by XX” (d’ E’ Comps beseten door XX) or “The honourable Company's (land) under XX” (d’ E’ Comps onder XX), indicating that the holders of the land were actually leasing it from the Company, which remained the land's ultimate owner. In 1685, Javanese headmen in this region had made a one-off attempt to challenge the situation by making a joint appeal for donation letters.Footnote 91 The College of Heemraden, however, noted that the land was merely provisionally (bij provisie) in their possession.Footnote 92

Figure 8. Javanese rural settlements.

Adapted from a cadastral map of c.1706, NA, Verzameling Buitenlandse Kaarten Leupe, VEL. 1186.

The path to full landownership would be further blocked by a decision of the High Government on 16 December 1701.Footnote 93 That decision forbade further land donations in rural Batavia and allowed the College of Heemraden only to rent (verhuren) land for cash revenue or give it in possession (in besit te geven) against payment of tithes, so that “the Company will have the most benefit and profit”.Footnote 94 Then, from 1703, when “diverse applicants” asked for full ownership of land “that they have for a certain period in possession and have cultivated”, the High Government resolutely refused, repeating that “no more land shall be given out” and that the College of Heemraden should require those applicants to pay “proper rent (huur) or tithes (tienden)”.Footnote 95 In 1706, the College of Heemraden even planned to restrict the leasehold of land, with a proposal to let the government, instead of private leaseholders, keep lease letters (leenbrieven) in order to make sure that “no one, after the death of the endowed, will come to own such lands”. But the proposal was, in the end, rendered unnecessary when the High Government found that the lease letters had already stated that “those lands can be neither sold nor alienated, but [will] fall back to the honourable Company”. It recommended only that the College keep a separate registry of leased land.Footnote 96

PLANTATION LABOUR

Without full ownership of their land, the Javanese rural community would take a different path to participate in the booming sugar economy. Although invisible in the land archives, that path is richly documented in the labour-recruitment contracts in the notarial archives of Batavia.Footnote 97 An interesting example is a contract signed between a Chinese sugar entrepreneur, Lie Poanko, and a Javanese commander, Wangsa, on 22 June 1703. Under the terms of the contract, Wangsa promised to provide twenty-three servants (dienaren) to a sugar mill belonging to Lie Poanko for the milling season of 1703, with the following division of labour:

Six servants mill sugar [canes] by day and night, namely 8 passos Footnote 98 of sugar [juice] by day and 8 passos by night. In case they mill less than 8 passos of sugar [juice] during a day or night, that day or night will be counted as if they milled no sugar [canes].

Four servants stoke the fire when the sugar [juice] is cooked, namely with firewood and dried bagasse. No bagasse shall be abandoned.

Ten servants cut the sugar canes in the fields and bring them to the mill.

Two servants cut the leaves of canes for feeding buffaloes.

One servant carries water that is necessary for the mill.

In return, Lie Poanko was to pay sixty-six rijksdaalders monthly to Wangsa, of which forty-one rijksdaalders would be retained until all the sugar cane had been milled.Footnote 99

According to the contract, Wangsa was a Javanese living in Pondok Bamboe (Pondok Bambu). Pondok Bambu was on the Company's land between the Small Cakung River and the Sunter River, which, as introduced in the last section, the Company parcelled out for provisional possession by many Javanese settlements. We know from the cadastral map of c.1706 that there was a Javanese lieutenant named Wangsa living in Pondok Bambu (Figure 8),Footnote 100 and it is probable that he mobilized his own followers to serve the plantation of Lie Poanko for cash revenue.

Wangsa was not the only Javanese commander-turned labour recruiter. In the same month of June 1703, another Javanese headman, Tsipta Wangsa, who also lived in Pondok Bambu, agreed to deliver twenty-four labourers for sixty-eight rijksdaalders per month to a Chinese sugar entrepreneur called Tan Kinko, whose mill was in Tsakong (Cakung) to the east of the Small Cakung River.Footnote 101 Again in the same month, a Javanese headman Carta Soeta, living in a place next to Pondok Bambu called Pondok Clappa (Pondok Kelapa) (Figure 8), agreed to deliver twenty-one workers for seventy rijksdaalders per month to Chinese miller Lim Tsiako, whose plantation was in Jatijnagara (Jatinegara), likewise situated between the Small Cakung River and the Sunter River.Footnote 102 Both those cases originated in a small space where sugar plantations and Javanese settlements were very close to each other, probably following an established model by which sugar plantations could draw seasonal labour from nearby villages during the milling season, in return for payments to village headmen.

As labour was mobilized collectively, a number of Chinese entrepreneurs would even outsource the entire milling job to a Javanese headman, without specifying how many labourers should be involved. For instance, in a case dated 9 May 1703, Javanese headman Jaga Soeta agreed to provide Chinese miller Ong Lieko with “as many servants as it shall be strong enough to do the following services for the sugar mill”, including cutting the sugar cane in the fields, carrying them in buffalo carts to the mill, milling sugar day and night, cutting leaves from sugar canes to feed the buffaloes, stoking the fire to cook sugar, and carrying water for the mill. The contract stipulated that all the above-mentioned services should be overseen by a Javanese supervisor (mandadoor) for a package price of sixty-six rijksdaalders per month, of which thirty-six rijksdaalders would be withheld by the Chinese miller until all that year's cane had been milled.Footnote 103

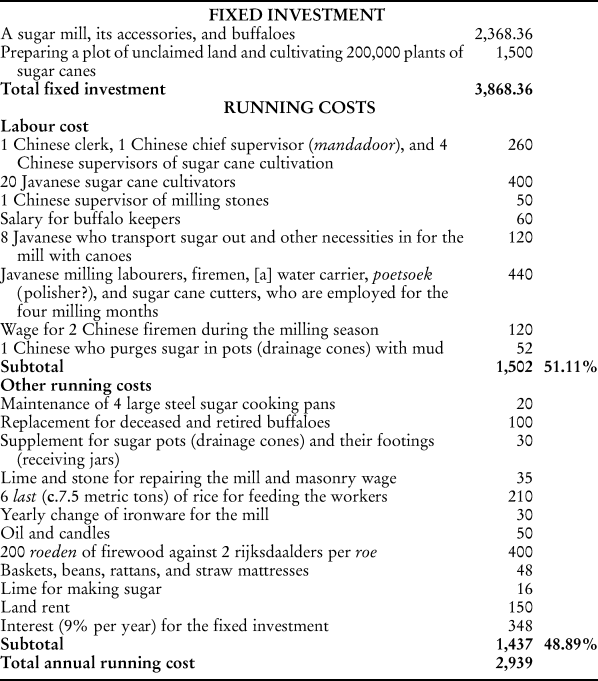

These notarized contracts reflect only part of the plantation labour regime, covering as they do only the milling season, which ran roughly from June to August, and which was also the high period of the dry season when sugar cane has its highest sucrose content.Footnote 104 Besides that, a sugar plantation in rural Batavia was a complex operation integrating milling and planting.Footnote 105 Sugar cane fields required year-round cultivation, which demanded permanent deployment of labour. A full account of the plantation labour regime is provided by a 1710 report (Table 1),Footnote 106 which reveals that more than thirty-six workers were employed year-round, including twenty-eight Javanese, eight Chinese, and an unknown number of buffalo keepers. A group of Javanese labourers and two Chinese firemen were recruited solely for the four milling months.

Table 1. Cost breakdown of a sugar plantation in rural Batavia (1710) (in rijksdaalders)

Source: Van Swoll and Van Zwaardekroon, “Uittreksel uit een rapport en uit de bijlagen over de suijkercultuur, in de ommelanden van Batavia”, pp. 158–160.

There was a notable ethnic division among the labourers. All the Chinese workers were identified with a certain skill and were paid much more than the Javanese.Footnote 107 The exclusively Chinese management team, consisting of a clerk, a general supervisor, and four supervisors of the sugar cane cultivation, collectively received 260 rijksdaalders per year, the equivalent of about 43.33 rijksdaalders per person. Wages for other Chinese technicians, such as the milling stone supervisor (sixty rijksdaalders), the two firemen (sixty rijksdaalders each), and the sugar-purging expert (fifty-two rijksdaalders), were even higher. By comparison, the twenty Javanese sugar cane cultivators received only 400 rijksdaalders per year collectively, or about twenty rijksdaalders each. The eight Javanese canoe crewmen earned as little as 120 rijksdaalders per year, or fifteen rijksdaalders each.

A preliminary observation is that Javanese plantation labour was paid less than contemporary urban unskilled labour but more than rural corvée labour. Considering that the cost of subsistence (barebones basket) in Batavia around 1710 was about twenty guilders (8.33 rijksdaalders),Footnote 108 the lowest paid of the Javanese – the canoe crews – with a wage of fifteen rijksdaalders (a subsistence ratio of 0.57 for keeping a family of a wife and two children)Footnote 109 were paid much less than free unskilled labourers in urban Batavia (subsistence ratio c.1.3) but slightly more than rural corvée labourers (subsistence ratio c.0.4).Footnote 110 It is, of course, worth noting that the watermen's work was less labour-intensive, for the milling season lasted only about four months and for the rest of the year they had no burdensome transport duties but merely supplied everyday necessities. The more intensive labour was done by the cultivators, whose wage (twenty rijksdaalders, subsistence ratio 0.76) was significantly higher than that of rural corvée labour. Moreover, given that the plantation workforce was given rice from the plantation they worked, their real subsistence ratio was actually much higher, for, according to the above-mentioned barebones basket model, food was an overwhelmingly important factor.Footnote 111

However, we should beware of over-interpreting these preliminary data, the sources of which were Chinese officers in Batavia.Footnote 112 Representing the interest of Chinese sugar entrepreneurs, they were lobbying for a higher sugar price through the report, and had probably overstated their cost. For instance, the reported cost of the Javanese milling team was 440 rijksdaalders for four months (Table 1), or 110 rijksdaalders per month, much higher than the wages in the above-mentioned contracts from the notarial archives, namely, approximately around 66–70 rijksdaalders monthly. It is, however, impossible to calculate the subsistence ratio of those seasonally employed milling labourers by merely referring to the contracts in the notarial archives, because they belonged to a rural society and were only seasonally mobilized as plantation labour by their headmen. For the rest of the year, they stayed with their families in the villages and lived as peasants.

Another question concerns how much money ended up in the hands of the workers. Each of the above-mentioned contracts was collectively signed by Javanese recruiters and Chinese sugar entrepreneurs and none made any reference to the actual incomes of individual labourers. The 1710 sugar report also provided only the collective Javanese labour costs. We therefore have no conclusive evidence to indicate whether or to what extent Javanese labourers were able to negotiate their wages individually with Chinese entrepreneurs. It might well have been the case that they received a different and discounted wage from their own commanders, who could charge an intermediary fee.Footnote 113 We shall bear in mind, too, that the commanders, as mentioned in the last section, were individuals authorized by the Company to collect tithes from their followers. Part of the cash income of Javanese labourers might have been withheld by their commanders to offset the costs of tithes or other taxation, and corvée.

Besides locally mobilized labourers, there were migrant labourers from villages outside Batavia, and they faced extra exploitation by inland rulers. A 1705 report by Cornelis Chastelein, an important Dutch official and landowner,Footnote 114 tells us that local rulers in Cirebon and Priangan (two partly Javanized regions in western Java) held the wives and children of Javanese migrant labourers who went to work for sugar plantations in rural Batavia as “bail” (borg), in order to ensure those labourers would return and pay the poll tax (hoofdgeld) for themselves, their families, and even their friends.Footnote 115 This poll tax, worth the equivalent of about a Spanish dollar (real) per cacah (corporate peasant household, unit of taxation) per year, was inherited from the Mataram period.Footnote 116 There were, therefore, complicated social factors that bound those particular plantation labourers to their native villages.

The involvement of migrant labourers indicates that the booming sugar economy was now mobilizing labour from beyond the border of rural Batavia. There is evidence that, as early as 1691, Wirabaja, a leader of a Javanese community in Karawang (Krawang), had made a contract with a sugar miller to send ten of his people to work for a year in return for 180 rijksdaalders.Footnote 117 Situated between Batavia and Cirebon, Karawang, as mentioned in the last section, hosted a Javanese colony established by the Mataram. In 1677, the Mataram ceded all its colonies in western Java to the Company. Amid this power transition, Wirabaja was one of the local rulers who shifted his allegiance to the VOC.Footnote 118 Perhaps he was quick to discover that he could benefit from Batavia's sugar economy if he mobilized his followers as plantation labour. Into the second half of the eighteenth century, former Mataram colonies outside the conventionally defined rural area of Batavia would become the major source of so-called bujang migrant labour, made up of unmarried boarders or farm servants, who, by then, had replaced villagers living within rural Batavia as the principal plantation workforce.Footnote 119

CONCLUSION

In 1710, there were 131 sugar mills in rural Batavia, each with a capacity of about 800 piculs Footnote 120 and with a total annual output of approximately 13,100,000 pounds, which was far more than the Company's approximately five-million-pound average annual order.Footnote 121 Wishing, therefore, to prevent a crisis of overproduction, on 10 October 1710, the Company introduced a restrictive sugar policy to halt further expansion.Footnote 122

The two and a half decades between the approval of Hiamtse's “perfect map” in 1685 and the restriction in 1710 were a definitive period in the formation of a Batavian sugar plantation society. Leaving behind a violent and tumultuous past, a unique plantation society emerged. This Batavian plantation society developed differently from the small-household sugar economy in South China where Chinese sugar production began.Footnote 123 Instead of being divided up for use by many peasants, its space was controlled by professional sugar entrepreneurs whose land rights were clearly defined by cadastral maps registered by the Dutch colonial company-state. It was different, too, from the slave plantations producing sugar in the Atlantic World, because the Batavian plantations drew their workforce from Javanese rural society. That society was deprived by the Company of full landownership and placed under Company-designated commanders, some of whom turned themselves into labour recruiters, mobilizing their own followers as plantation labour for which the recruiters signed collective wage contracts with Chinese sugar entrepreneurs.

Hiamtse's “perfect map” offers a unique angle from which to observe how such a plantation society took shape on the ground. It manifests a reconfiguration of land and labour in rural Batavia in the wake of the colonial expansion of the Dutch empire in the early 1680s. That expansion secured Batavian sugar from war and competition, on the one hand, thereby preparing the way for the industry to benefit from a sugar boom; on the other hand, it transferred Dutch land culture to Batavia, which gave a prominent role to the cadastral maps comprehensively measured by European land surveyors, known as “perfect maps”. Those changes were soon appropriated by plantation owners like Hiamtse, who actively negotiated with the reformed Dutch rural council (College of Heemraden) to acquire perfect maps to enable herself not only to secure the precarious sugar enterprise she had inherited from her late husband but, moreover, to expand it. Nevertheless, perfect maps also played a role in the marginalization of the Javanese rural community, whose leaders usually held only vaguely defined land documents. Without full land ownership but with many followers, they therefore joined the booming sugar economy as labour suppliers. Collective wage agreements with Chinese entrepreneurs enabled them to exploit their followers as plantation labour. As a result of this chain of interactions, a Batavian sugar plantation society emerged in early modern Southeast Asia combining comprehensively mapped space and villagers-turned-labourers.

Such a case should also encourage us to rethink plantations in early modern global history, for it serves as a healthy reminder to destabilize an overarching framework that ties early modern plantations with the Atlantic World, slavery, sugar, and European colonial expansion. It reminds us that beyond that framework lay different configurations of land, labour, commodities, and power, leading to multiple models of plantations related to different local interactions with different kinds of early modern globalizations. For instance, Batavian sugar plantations were merely one type of plantation among others in early modern Southeast Asia. In the perkenier system in Banda, from the early seventeenth century, the VOC assigned slaves and land to nutmeg planters (perkenier) for a monopolistic and restrictive model of production.Footnote 124 In late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Jepara and Kudus on the north coast of central Java, Chinese sugar entrepreneurs contracted the land and labour of entire villages from local Javanese rulers, and enjoyed “a share of the villagers’ corvée”.Footnote 125 Amid a new wave of Chinese overseas agricultural expansion beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, pepper and gambier plantations employing migrant labour from China appeared in Riau.Footnote 126 We may expect more scholarly attention being paid to such non-Atlantic early modern plantations to shed further light on the plurality of plantations in global history.