INTRODUCTION

The construction of infrastructure in Cuba, whether for imperial defense or private economic interests, was carried out by a shifting combination of state and local actors, often with motley crews of forced and free laborers. Because Cuba did not have a substantial indigenous population beyond the middle of the sixteenth century, many of the laborers for construction projects were involuntary migrants from Africa or from other regions of the Spanish Empire. In this sense, Havana's port was also the site of first arrival for many of the people who built and labored in the city and extended the empire's economic and political reach into the countryside. The port's infrastructure projects also served as a testing ground for different mixes of forced and free laborers in completing difficult, unskilled work. The consolidation of the social and economic structures of plantation slavery in the first third of the nineteenth century in Cuba framed all later experiments with labor. The experiences of Cuban officials in the road and rail projects from 1790 to 1835 informed their successors’ resort to indenture to supplement enslavement in both public and plantation work by the 1840s, and their insistence on maintaining the controls of slavery over workers who were legally freer.

As this brief summary suggests, freedom and unfreedom were not absolute opposites in theory or practice for workers in Cuba in the eighteenth and nineteen centuries. The levels of violence and constraint experienced by the laborers discussed in this essay in the areas of recruitment, compensation, and “control over the working body” demonstrate most clearly the range of coercion that employers applied to workers of varying status in Cuba, from the enslaved and indentured to convicts and to those who were legally free.Footnote 1 In the context of a society in which enslavement was deeply embedded and expanding, employers sought to extend the controls applied to slaves – shackles and chains, the lash, and the barracoon – to workers who were not enslaved by law, though workers’ resistance did limit the success of these efforts. At this time, Spanish law defined “free” persons as those not bound by the strictures of slavery, by which another person owned both the slave's body and labor, or by a judicial sentence or contract to labor for a given period. This essay seeks to illuminate the many ways that both the free, the enslaved, and those in between in colonial Cuba were subject to violence and coercion as part of their work for the state. Thus, the terms free and unfree highlight the contingent and broad nature of both categories in the work regimes imposed on laborers in road and rail projects of colonial Cuba.

FROM IMPERIAL SERVICE TO PLANTATION EXPORT

For the first two centuries of colonial rule, Havana's orientation and connections were largely maritime. Goods, capital, and labor arrived from other Spanish Caribbean ports such as Cartagena de Indias or Veracruz, or from the metropole across the Atlantic. The Spanish Crown sought to control imperial trade and migration to the island by funneling it through designated ports such as Seville and later Cádiz, and Veracruz. However, unlike many other colonial ports in Spain's American empire, initially Havana's primary function was not to be an outlet for goods produced in Cuba. Rather, as historian Alejandro de la Fuente has noted, “it was the port that made the hinterland”, though this process was a slow one.Footnote 2

Havana became the gathering site for the convoys returning to Spain in the 1550s and maintained that role into the late eighteenth century. Infrastructure investment around the port by the crown from the late 1500s to the 1700s focused on securing the city and its bay with forts and a wall to deter pirate or imperial rivals’ attacks from the sea. In addition, the vast majority of the people who built and sustained the city and its port also arrived by sea or were descended from those who had done so, making Havana a diverse and cosmopolitan place even in its first century as a Spanish colonial port.Footnote 3

Unlike other Caribbean colonies such as Barbados or Saint Domingue, the Havana region developed into a major producer of tropical products for export only after 1750, recasting the port's role in the empire and its infrastructure needs.Footnote 4 Though the port's maritime connections continued to be vital and expand throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, by the 1790s the orientation of infrastructure investment shifted inward to extend a network of roads, and later rails, to link Havana's widening plantation hinterland to its port to ensure the transport of sugar and coffee to overseas markets.

Cuba's shift to slave-based plantation production also transformed its demography as the white population was overshadowed by a rapidly growing enslaved and free population of African descent in the first third of the nineteenth century. Enslavement and other forms of forced labor were long-standing practices of conquest and colonization in the Spanish Empire. Though full-blown plantation economies were a late development, the execution of defense works for the key imperial ports such as Havana often relied on coerced laborers.Footnote 5 For example, by the eighteenth century, as the Spanish monarchy contended with growing French and English power in the Americas, the Spanish crown expanded its use of state-owned enslaved workers to better fortify Cuba after the British occupation of Havana ended in 1763. Over the next three decades, colonial officials on the island also experimented with ways of forcing legally free people to do defense and civil construction and to serve in the military through levies during the revolutionary era in the Caribbean.Footnote 6

For Cuba, militarization and state investment in defense were coupled with Crown concessions to liberalize trade and state-private efforts to foment economic development. By the time slave rebellion in nearby Saint Domingue had destroyed that island's booming planation sector, Cuba was poised to take its place. Hence, the period from 1790 to 1840 saw major transformations in Cuba as elites and colonial officials collaborated to foster plantation development and to better defend the island. At the heart of these transformations was the shift in the island's economy from imperial service to plantation production of coffee and sugar for export.Footnote 7 This transformation was demographic and geographic; plantations spread out from the Havana region into new parts of the island, creating explosive demand for enslaved workers. This demand for labor and the relaxation of imperial controls on the slave trade brought more than 536,000 enslaved Africans to Cuba over the fifty-year period.Footnote 8

These demographic transformations prompted concerns among the Cuban elite about the “Africanization” of the island's population, particularly in light of the revolutionary upheaval in Saint Domingue that culminated in the declaration of a black republic in 1804.Footnote 9 Proposals debated over the next forty years all sought to increase white migration to Cuba, though members of the elite differed over whether continuing the importation of African slaves was wise. The proponents of white immigration also differed on whether to recruit white families with offers of modest plots of land for farming or single white men to work for a wage on plantations.Footnote 10 How best to increase the numbers of available laborers in Cuba for both state-sponsored projects and agriculture remained a challenge throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, but there was little debate about the desirability of increasing sugar production to fill the void left in the world's supply after the collapse of Saint Domingue. The experiments to recruit labor for infrastructure projects informed and were informed by the consolidation of plantation slavery in Cuba. Elites were particularly concerned about where a given group of workers would fit in the racial hierarchy and whether the costs to recruit, maintain, and control those workers were sustainable.

In addition to recruiting labor, the geographic expansion of plantations necessitated the construction or repair of roads to ensure the efficient transport of export products to the port of Havana, especially for the more perishable export, sugar. Into the eighteenth century, road building and repair had been carried out by private householders in the countryside, employing local, free, and enslaved laborers. Many travelers to Cuba reported on the disastrous state of its roads, especially during the rainy season. The most famous traveler of the early nineteenth century, Alexander von Humboldt, noted from his visits in 1800–1801 and 1804 that the streets of Havana were “disgusting […] because one walked up to the knees in mud”. Roadways leading out of the capital were no better as “[t]he interior communications of the island [were] laborious and costly, in spite of the short distance […] between the northern and southern coasts”.Footnote 11 Decades of local efforts brought little progress in road repair and construction, as weather and wear took their toll. Von Humboldt favored the digging of a canal to improve north-south transport, but this project never came to pass.Footnote 12

After an intense period of the colonial state employing enslaved and other coerced workers to build and repair the defense works of Havana (1763–1790), Crown officials, many of whom had become planters themselves, began to intervene to speed road construction and repair to outlying plantation districts. Initially, the captains general tried to encourage, then force, free householders to do the work of road and bridge construction themselves, with scant success as many claimed their military service as grounds for an exemption from road work.Footnote 13 The failure to coerce local free people to extend the road network stimulated Cuban elites and colonial officials to explore other options. By the 1790s, wealthy creole planters petitioned the Spanish Crown for control of the labor of captured fugitive slaves to advance road construction, again with only limited success. Finally, the obstacles to transportation construction were overcome by recruiting contract laborers abroad and undermining the liberty of Africans freed by British anti-slave trade treaties to build the first rail line in Latin America, from Havana south and east to Güines; the line was finished in 1838.Footnote 14

Thus, capitalist development of the export economy in Cuba was closely intertwined with the imperial state's policies and practices of labor recruitment and deployment in public works. The state and its contractors sought to hold down labor costs and exert control over workers’ mobility and pace of work by experimenting with a range of coercive labor forms, such as enslavement, penal labor, and apprehensions of vagrants and fugitive slaves. The analysis here shows that the experiments with varied types of forced labor that successfully completed road and rail networks shaped later labor experiments on plantations, when African slavery was disrupted by the long process of abolition in the Atlantic world.

COLONIAL PRECEDENTS IN LABOR RECRUITMENT BEFORE THE 1790s

Much of the colonial infrastructure of Havana was built with combinations of forced and free labor. The construction of the earliest forts to guard the port employed state- and privately owned slaves, prisoners, and free workers from the local population, Africa, and Europe.Footnote 15 By the mid-eighteenth century, as the city's strategic importance to the empire grew, the Spanish Crown subsidized Havana's defenses with Mexican silver and increasing numbers of forced laborers, both slaves and convicts, employed in defense works.

The height of the use of state slavery for Havana's defense works came immediately after the British occupation of Havana in 1762. The Spanish Crown purchased over 4,000 African slaves in the king's name to build and repair its fortifications. The costs of maintaining such a large cohort of state slaves quickly led the Crown to reduce their numbers and supplement them with more imperial prisoners, mainly those sent from Mexico to the forts of Havana as part of their sentence.Footnote 16

The Crown's efforts to better defend Havana and wage war over the eighteenth century brought more Spanish troops to the city, increasing concerns about the disorderly behavior and desertion of military men and others.Footnote 17 Colonial officials also faced the devastation of recurring hurricanes, which damaged roads and bridges with frustrating regularity.Footnote 18 The exigencies of wartime and environmental disasters resulted in greater state intervention in infrastructure projects, particularly in the recruitment and coercion of labor. With Crown support, colonial officials expanded the definitions of vagrancy and even resorted to forced levies to keep order and complete the port's defense works during the cycles of Caribbean warfare in the late 1700s.Footnote 19

In a series of royal orders over the eighteenth century, the Spanish Crown defined more clearly the category of vagrant and its negative connotations. A royal order from 1717 defined those who could be subject to levies of vagrants as “bad living people” with “no honor”.Footnote 20 By 1745, the Crown had issued another order that expanded its definition of vagrancy and delinquency to cover all who had no trade, home, or income, and lived “not knowing from what licit and honorable means their subsistence might come”.Footnote 21 The order included both the unemployed and the underemployed who did not find productive activities to occupy their time during dead seasons. The delinquent included gamblers, drunks, the sexually promiscuous or adulterous, pimps, and disobedient children. Crown officials also distinguished between “deserving” beggars, who merited compassion and charity, and “false”, able-bodied beggars, who were to be prosecuted as vagrants.Footnote 22

The metropolitan approach also revealed a growing effort to centralize the holding of captured vagrants under royal control and to harness their labor. In the 1730s and 1740s, the Crown ordered that vagrants be detained and held in jails, sending the able-bodied among them to army service or public works. In 1775, Charles III authorized annual levies to round up vagrants, and in the later 1770s shelters were established in Madrid to hold them. In 1779, when Spain joined France to intervene in the American War of Independence, the king set the term of service at eight years for captured vagrants sent to the army. The Crown continued to publish bans against vagrants, beggars, and foreigners every few years over the next two decades.Footnote 23

In Cuba, colonial officials employed metropolitan directives to extend their authority out from Havana into the countryside. Before 1762, the deputizing of patrols to track down enslaved fugitives and military deserters had rested with the local town governments, but this power was appropriated in moments of crisis. For example, in 1765, Captain General Ricla created a rural police and judiciary force that reported directly to him and the captains of partidos (districts of the interior).Footnote 24 As the Captain General's representatives in the countryside, the captains of partidos were charged with maintaining good order and seeing to the needs of the local population. After a terrible hurricane in 1768, Captain General Bucareli also sent out groups of soldiers to round up escapees. The king ordered that those apprehended as vagrants be employed in Crown projects or on public works, or be exiled from Havana altogether.Footnote 25

Times of emergency allowed the colonial state to extend its power and create new corps to enforce that power. Once extended, the state rarely returned power to the localities. Still, as historian Sherry Johnson has argued, for several decades after the British occupation the governors in Havana maintained a reputation for good government, at least with the “better” classes, through their attention to the public welfare during disasters, which helped justify and control resistance to their extension of power.Footnote 26 The constant stream of desertions and reports of delinquency from the captains of partidos suggests that many of those pressed into military service or defense construction were less appreciative.Footnote 27

Bucareli's successor as Captain General, the Marqués de la Torre (1771–1777), enjoyed a brief respite from warfare and was able to perfect the mechanisms of capture and deployment of a range of transgressors to carry out a major program of urban renewal that included street paving in Havana and the building of bridges on thoroughfares out of the city. To stem the tide of military desertions and flight from work sites, De la Torre established both uniformed and plain-clothes (disfrazados) patrols to search for fugitives, centralizing some components of the apprehensions begun under his predecessors.Footnote 28 Captors notified the Captain General of an apprehension and requested reimbursement for maintenance costs, transport, and fees.Footnote 29 His office began keeping track of the deserters recaptured in 1775, reporting a total of sixty-four rounded up by the end of his term in 1777.Footnote 30 The growing size and complexity of Havana, in both its spatial and human dimensions, spurred De la Torre and his successors to expand the state's powers of coercion to control the swelling numbers of people trying to escape military service or the more restrictive norms of decent behavior, with the approval of Cuban elites.

When De la Torre turned over the reins of government to his successor Diego Navarro in 1777, he highlighted his efforts at improving policing to ensure the “tranquility and good order” of Havana and its benefits in recruiting labor for public works.Footnote 31 He claimed to have sent 8,263 people to jail in less than six years, though most spent little time behind bars because the usual punishment was to “send them to public works for more or less time according to the crime”.Footnote 32 Colonial officials scrambled to find labor for fort projects in the 1760s and had looked outside Cuba for forced labor – purchasing the king's slaves in the mid-1760s – and then shifted to requesting more imperial convicts from Mexico. While De la Torre continued to use both state slaves in smaller numbers and convicts to finish defense works, he turned the state's coercive power on the island population to find labor for civil construction projects in the 1770s. His successors continued to persecute and prosecute the “vice-ridden and evilly entertained”, but found diminishing returns with this policy for staffing road-building projects.

During the years of Spain's intervention in the American War for Independence (1779–1783), the captains general of Cuba resorted to levies on the free population to recruit troops for the army and navy and laborers for defense works.Footnote 33 Many free people, both white and of color, also volunteered for militia service during the war. The end of hostilities in 1783 found much of the Cuban population exhausted after the considerable sacrifices demanded by the war effort; this complicated the search by state officials for labor to build and repair roads.

PRESSURE ON FREE PEOPLE FOR ROAD WORK

The captains general who served from the mid-1780s to the mid-1790s found free Cubans less willing than they had been in the late 1760s and 1770s to volunteer for road construction. Of particular concern were the roads and bridges to the south and east of Havana toward Güines and Matanzas, where some of the greatest sugar and coffee expansion was concentrated. Even before the revolution in Saint Domingue in 1791 opened greater opportunities for Cuban planters in the world market, sugar production had begun to grow substantially. Sugar exports through Havana doubled in the decade from 1776 to 1785, then more than doubled again between 1785 and 1800. By 1840 sugar exports from Havana had reached 26.6 million arrobas, an almost twelvefold increase (Table 1).

Table 1. Sugar exported from Havana 1776–1840 in arrobas.

Sources: Pablo Tornero Tinajero, Crecimiento económico y transformaciones sociales: esclavos, hacendados, y comerciantes en la Cuba colonial (1760–1840) (Madrid, 1996), Appendix 3, p. 383, for 1776–1820 and 1826–1840; Von Humboldt, Ensayo político, p. 218, for 1821–1825.

Already by the mid-1780s, colonial officials were meeting resistance in recruiting labor for road and bridge works, though some progress was made by sending out groups of coerced workers in the state's charge to the projects. Captain General Ezpeleta (1785–1790) sent numerous requests to his captains of partidos in the region to require local householders (vecinos) to give two days per week to road and bridge building and repair or to send several slaves or farmhands in their stead. He often received long reports of reasons why local vecinos could not or would not comply, particularly from those whose military privileges freed them from labor in public works. To advance the road projects, Ezpeleta gave the contractor in charge of the works access to a number of captured deserters, fugitive slaves, and escaped convicts. Ultimately, this infusion of forced laborers had some success in improving the road networks between Havana and the growing plantation areas in the second half of the 1780s.Footnote 34 Ezpeleta's successor was not so fortunate.

In the summer of 1790, Luis de Las Casas arrived in Cuba as the new Captain General and a dedicated supporter of sugar expansion. Plantation owners sought to ensure his long-term favor by presenting Las Casas with a plantation of his own, complete with machinery and enslaved laborers.Footnote 35 One way that Las Casas sought to reward their generosity and reap the maximum benefit from his plantations was to advance the road-building projects. He had an ambitious plan to connect Havana to other Cuban ports by land, with trunk lines to the port of Matanzas to the east and Batabanó to the south, as well as roads to inland regions with essential timber and plantation products such as Güines.Footnote 36

Las Casas began his road building program with an order in late 1790 for all able-bodied men to report for road work. Almost immediately, captains of partidos began reporting resistance, such as an unruly crowd in a small town southeast of Havana refusing to report for road duty. The ringleaders were sent to Havana for a personal admonishment by the Captain General, who warned them to respect the authority of their local captains of partidos. Footnote 37 Las Casas continued to press the captains of partidos to force locals to do road work, but vecinos claimed military privileges, illness, and even bad roads as reasons why they could not comply.Footnote 38 In short order, even the government's representatives in the countryside joined the effort to resist the Captain General's orders for free vecinos to perform road work. When pressed by Las Casas to produce workers, town mayors and some of the captains of partidos themselves responded with excuses or not at all.Footnote 39

A severe hurricane in 1791 caused extensive loss of life and washed out bridges and roads, but further orders from Las Casas to round up the “idle” and “evilly entertained” yielded few laborers. When the Captain General ordered the captains of partidos to conduct censuses of their jurisdictions’ population, several submitted drastically reduced numbers or tried to resign their posts. Las Casas then tried to arrest resisters, putting some in stocks as an exemplary punishment or sending them to road projects as prisoners. Ultimately, the Captain General failed to win the compliance of his underlings or the people they were supposed to recruit. By October 1796, he had admitted defeat on advancing road projects with free laborers and was recalled to Madrid.Footnote 40

EXPERIMENTS WITH CAPTURED FUGITIVE SLAVES

Las Casas's failure to compel free people to do road work necessitated finding other groups of people with fewer ways to resist. The demographic transformation of the Havana region with the influx of thousands of enslaved Africans provided a new group that could be coerced by the state for road work. Captain General Las Casas worked with Havana-area planters through quasi-governmental organizations to advance their mutual interests in road expansion. Organizations such as the Havana Consulado brought together wealthy planters and merchants with colonial officials to foment plantation development and adjudicate commercial disputes. The Consulado also became a new vehicle through which to execute infrastructure projects.Footnote 41

In the wake of the slave rebellion in Saint Domingue, planter members of the Consulado, Joseph Manuel de Torrontegui and Francisco Arango y Parreño, proposed to the Crown the centralization of the capture and warehousing of fugitive slaves as a necessary security measure and a remedy for the challenges of recruiting laborers for road work. Showing parallels to state policies of the previous twenty years centralizing the disposition of military deserters, Torrontegui and Arango suggested that the Consulado regulate expeditions of capture and control the disposition of fugitive slaves thereafter.Footnote 42 Their report asked the king to allow all captured fugitive slaves to be assigned to public works and to remain in that service without time limit, unless the owner came forward and could pay the costs of the slave's capture.Footnote 43 In late 1796, the king agreed and the Consulado became the major beneficiary of their labor on the island.Footnote 44

In spite of having a reasonably low-cost group of laborers at its disposal, the Consulado was not successful in greatly expanding the road system of Cuba over the next thirty-five years. The perennial problem of torrential rains and geographically scattered sites bedeviled the Consulado's projects, such that only 25.4 kilometers were completed by 1831.Footnote 45 In contrast to the road-building projects of the 1830s and 1840s, in the expanding British Empire in Asia discussed in Clare Anderson's essay in this Special Issue, by the mid-nineteenth century the shrinking Spanish Empire did not have significant cohorts of convicts to transport to Cuba for such projects. Dramatic improvements in internal transport in Cuba had to await the construction of railroads in the late 1830s and the resort to coerced laborers from beyond the island and the empire.

EXPERIMENTS WITH EMANCIPADOS AND CONTRACT LABORERS

The Cuban railroad-building projects of the mid-nineteenth century show well the patterns of coercion that were most successful for infrastructure building in Cuba. Unlike railroad building in other colonial settings, the main actors in organizing the first rail project included Havana-dwelling Cubans who also owned plantations outside the city. These planters used their connections in Europe and North America to find the necessary capital, technology, and skilled and unskilled labor to build the first rail line to the growing sugar area of Güines, southeast of Havana.

Though there was a growing enslaved population, high slave prices privileged their employment in the most profitable sectors of the economy. Relatively high wages in other sectors and miserable working conditions on rail projects kept most free workers from choosing labor in public works. Additionally, similar to planters in the private sector, the railroad projects’ promoters had to recruit labor in a vastly different labor market from 1820 onward. Anti-slave trade treaties with Great Britain in 1817 (taking effect in 1820) and 1835 succeeded in disrupting the flow of African slaves to Cuba and raising prices. Spain abolished slavery in the metropole in 1836 and the British officially emancipated the slaves in their empire by 1838, causing Cuban slave owners to fear the eventual end of slavery on their island as well.Footnote 46 Colonial officials began to experiment with contract labor in the 1830s to ensure lower costs and sufficient work discipline to complete the first railroad line in Cuba. Their experiments with contract labor for infrastructure building were adapted to the needs of the plantation sector less than twenty years later, as legal access to enslaved workers from Africa through the transatlantic slave trade contracted by the late 1840s.

The labor force for building the first rail line out of Havana into its hinterland came to include virtually every kind of forced and free laborer ever employed in the colony. The work, similar to plantation labor, fort building, and road work, was arduous and largely unskilled labor, rarely attracting free laborers at the low wages the promoters were willing to offer. An 1837 report from the commission that oversaw the first rail project, lamented that, in Cuba, where “daily wages are so high and hands always scarce for the urgent work of agriculture, workers are not to be found”.Footnote 47 From 1835 to 1838 the rail line's workforce contained some slaves owned by or housed in the Havana Depósito for runaway slaves and the nominally free Africans known as emancipados. Footnote 48 Similar to the labor crews discussed in Martine Jean's essay on the building of the Casa de Correção in Rio de Janeiro in the same period, the British efforts to end the transatlantic slave trade generated a new group of laborers who were legally free but suffered virtual re-enslavement in areas such as Cuba and Brazil, where slavery was not abolished until 1886 and 1888, respectively. Other workers on the rail projects were convicts – Cubans or criminals sentenced to the island from other parts of the empire. The composite group of forced laborers numbered about 500 per year over the three-year span.Footnote 49

Figure 1. Roads Proposed and Rail Lines Built, Havana Region, 1790–1850.

Though some state-owned and captured fugitive slaves and hundreds of emancipados were assigned to the railroad project, the demands of other public works, like road repair, and the 209 deaths among rail workers necessitated a search for new alternatives to recruit workers, while retaining mechanisms of control.Footnote 50 Although there had been discussion since at least the late eighteenth century of encouraging white immigration to Cuba, the railroad commission's contracts were the first large-scale initiatives in that direction.Footnote 51

When the Consulado's development board, the Junta de Fomento, contracted engineers Alfred Cruger and Benjamin Wright Jr. from the United States, it empowered them to recruit between 800 and 1,200 workers with some construction experience who might be idle during the winter months in New York. The Junta also allowed for the recruitment of overseers who would form their own crews. Wright used established networks in the United States to contract with workers, some of whom had labored there in canal building. Working through the Spanish consul in New York, Francisco Stoughton, the Junta made contracts with overseers, who paid their crews and promised to finish specific portions of the rail line.Footnote 52 One such contractor, John Pascoe, brought along his wife and two children.Footnote 53 Another contractor, named Erastus Denison, was hired by the Junta because he had shown his knowledge of the “construction and use of machinery in general, in the construction of works in the water, in all branches of common works of mechanics, including steam machines and locomotives”. He would be paid 110 pesos per month for at least six months, though the contract could be extended to one year.Footnote 54

Those who contracted to go to Cuba as peones and operarios (unskilled workers) were to be paid only twenty-five pesos per month, though this wage was almost double or more than the wages offered to any of the other groups of the unskilled. Those laborers working with explosives would be offered “something more”. The contracts were for six months but could be extended to one year at the discretion of their employer. The Junta would provide shelter, but all other maintenance would be at the expense of the workers. Their contracts also required them to pay back the costs of their passage and provisions for the voyage through deductions from their wages. The Junta clearly had high hopes that this white, largely Anglophone cohort would prove to be exemplary workers, with some knowledge of either canal or railroad building, at a relatively modest cost.Footnote 55

In Cuba these contracted workers from North America were called irlandeses, “Irish”, although there were some other nationalities in the group. There are varying estimates of the size of this group. British abolitionist David Turnbull, who visited Cuba in 1837, reported that “upwards of a thousand Irishmen” came to work on the railroad. Margaret Brehony has confirmed Turnbull's guess, estimating between 800 and 1,200 irlandeses in the cohort that built the Havana to Güines rail line.Footnote 56

The irlandeses began arriving in November 1835. Even though their pay was high by Cuban standards, some were already heavily indebted to the Junta before leaving New York, meaning that their first few months in Cuba would have been lean indeed.Footnote 57 By spring of 1836, some of the irlandeses had returned home; some had deserted the railroad sites, but did not have the resources to book a return passage. Both the American and the British consuls received pleas from destitute workers from North America for help paying for a passport and passage back home. The American consul Nicholas Trist reported paying sixty dollars to a young woman, who had come to Cuba with her husband, to help her return via New Orleans with her two young children.Footnote 58

The Junta decided that their resort to North American contract laborers, at least the unskilled peones, was too expensive and created problems even after the workers had left the rail works. The chief engineer Cruger blamed the workers themselves, angered by what he called their “drunken state”, insubordination, disobedience, and complaints about low pay and work conditions. He thought any who were unhappy could go back to the US “at their own expense”.Footnote 59

The irlandeses were a short-lived experiment with indenture that helped advance the first railroad line only briefly and revealed some of the dangers of importing culturally alien workers who could not be subjected to the lash and shackles, as were the enslaved and prisoners. The irlandeses resisted through drink, disobedience, and desertion. Since the state refused to pay for their return to the US or allow them to work on their own account elsewhere, some of them appeared idle and destitute in the streets of Havana after their contracts were completed.

The Junta de Fomento initiated another experiment with contract labor within the Spanish Empire that succeeded in recruiting a similar number of workers as the North American venture, but at a lower cost and with more control. In 1835, the Junta contracted several Spanish ship captains to recruit bonded laborers in the Canary Islands for work on the rail line. One contract with Captain Nicolás Domínguez in April 1836 stipulated that the captain would be paid up to forty-five pesos for the passage and passport or license of each worker. Those contracted had to be between twenty and forty years old and “apt to be employed” in building the railroad. The workers had to agree to be employed in the rail works or on another Junta project at least long enough to pay back the costs of their passage, paying three pesos per month until the debt was cleared. They would be paid nine pesos per month and provided with shelter, food, and medical care for up to one year. Though the Canary Islanders, called isleños in Cuba, received some maintenance, unlike the irlandeses, their pay was even less than the wage offered to hired slaves. These workers also had to agree not to desert the rail works before covering the costs of their passage, under penalty of a hefty fine of twenty-four pesos, plus the cost of their apprehension.Footnote 60 This strategy produced the largest group of contract laborers for the first rail project, a total of 927 Canary Islanders. However, by the time the rail line opened two years later in 1837, only seven remained working on the railroad, in part due to the miserable conditions under which they labored. One hundred and fifty-six of the Canary Islanders had died, another thirty-five were incapacitated, and eighty-four had fled the rail works.Footnote 61

Some of the Canary Islanders tried to remedy what they saw as ill treatment by complaining to authorities that they were not paid regularly and were given disgusting food. Some protested with sticks and knives about their miserable living and working conditions. In both cases their complaints were either ignored or repressed. To the charges of late pay and rotten food, the Junta countered that their contracts did not stipulate when exactly they would be paid and that the isleños only ate cornmeal and fish at home, so the food in Cuba was sufficient. In response to the more vigorous armed resistance, the Intendant the Count of Villanueva ordered that the protesters who were apprehended be sent back to the rail project in chains for two months.Footnote 62

It is not surprising, therefore, that the contracted Canary Islanders suffered high rates of death and frequently tried to flee the rail works. Death and desertion among them rose to almost twenty-six per cent over two years. When added to those workers who were incapacitated, the Junta's losses rose to almost thirty per cent. The Junta was particularly concerned about desertion among the Canary Islanders, since they could easily blend into the larger Hispano-Cuban population. The Junta tried to impose high fines on anyone who might harbor a fugitive worker. Most of the isleños would have been fluent in Spanish and, as the Junta reported, there were “sound reasons to fear that they might desert, favored by the multitude of persons of the same origin who were well established on the island”.Footnote 63

Both schemes for white immigration from the United States and the Canaries were bedeviled by high mortality and desertion, a testimony to the difficult and unhealthy conditions under which these workers labored. Still, their work ultimately may have ensured the successful completion of the first rail line, extending opportunities for successful plantation expansion far beyond the port of Havana to the south and east.Footnote 64

By 30 June 1837, the total number of workers on the rail line was 742 men; only seven of the contracted isleños continued working on the railroad. Various contingents of enslaved and recently freed men of African descent remained, almost sixty-five per cent of the total workforce – eighty-seven emancipados diverted by the Junta from work on Havana's aqueduct, 145 of the Junta's own slaves, and between 200 and 250 of the Junta's fugitive slaves. The remaining workers were employed by the various contractors in transport of materials, stone work, and excavation, though the Junta did not keep track of their numbers or fortunes.Footnote 65

After one year of extensive use of contract workers on the railroad project, the Junta returned to using mostly enslaved workers from among those at its disposal. Similar to the hasty purchase of large numbers of state slaves in the defense works of the 1760s, the Junta's recruitment of European, North American, and Canary Island contract workers provided the surge of coerced labor that the project needed to initiate rail construction. The costs and problems encountered with the resort to thousands of kings’ slaves in the 1760s and hundreds of contract workers in the 1830s encouraged the return to employment of coerced workers whose recruitment did not involve major investments and over whom the projects’ supervisors had significant control. In the case of the first rail line, slaves, some owned by the Junta and some captured in flight from their owners, came at lower cost and could be more easily controlled, due to their unfree status.

The contracting of white laborers for plantation work would not be the long-term answer to the vagaries of the illegal slave trade to Cuba. Indentured Canary Islanders, especially, could desert too easily due to their whiteness and Spanish language. Similar to other Caribbean plantation colonies in the mid-nineteenth century, Cuban elites and officials eventually turned their attention to Asia and Mexico for laborers perceived as racially different enough to provide low-cost, bound labor on plantations. Funds were invested in the immigration of yucatecos (largely Mayans or mestizos from the Yucatan peninsula) and Chinese as indentured laborers, whose contracts obligated them to accept wages well below the Cuban norm for both free wage earners and hired slaves.Footnote 66 The prices that planters paid to purchase their contracts were also considerably lower than the prices for African slaves; from 1845 to 1860 prices for Chinese indentures were less than half those of slaves.Footnote 67 Though the numbers of yucatecos imported into Cuba were small, Chinese indentured laborers arrived in much larger numbers, over 120,000 from 1847 to 1874.Footnote 68 Conditions for these contract workers were so terrible that the governments of their home countries ultimately curtailed their trade to Cuba.Footnote 69

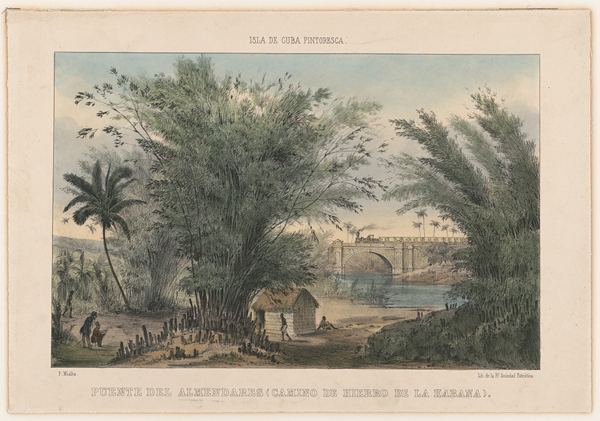

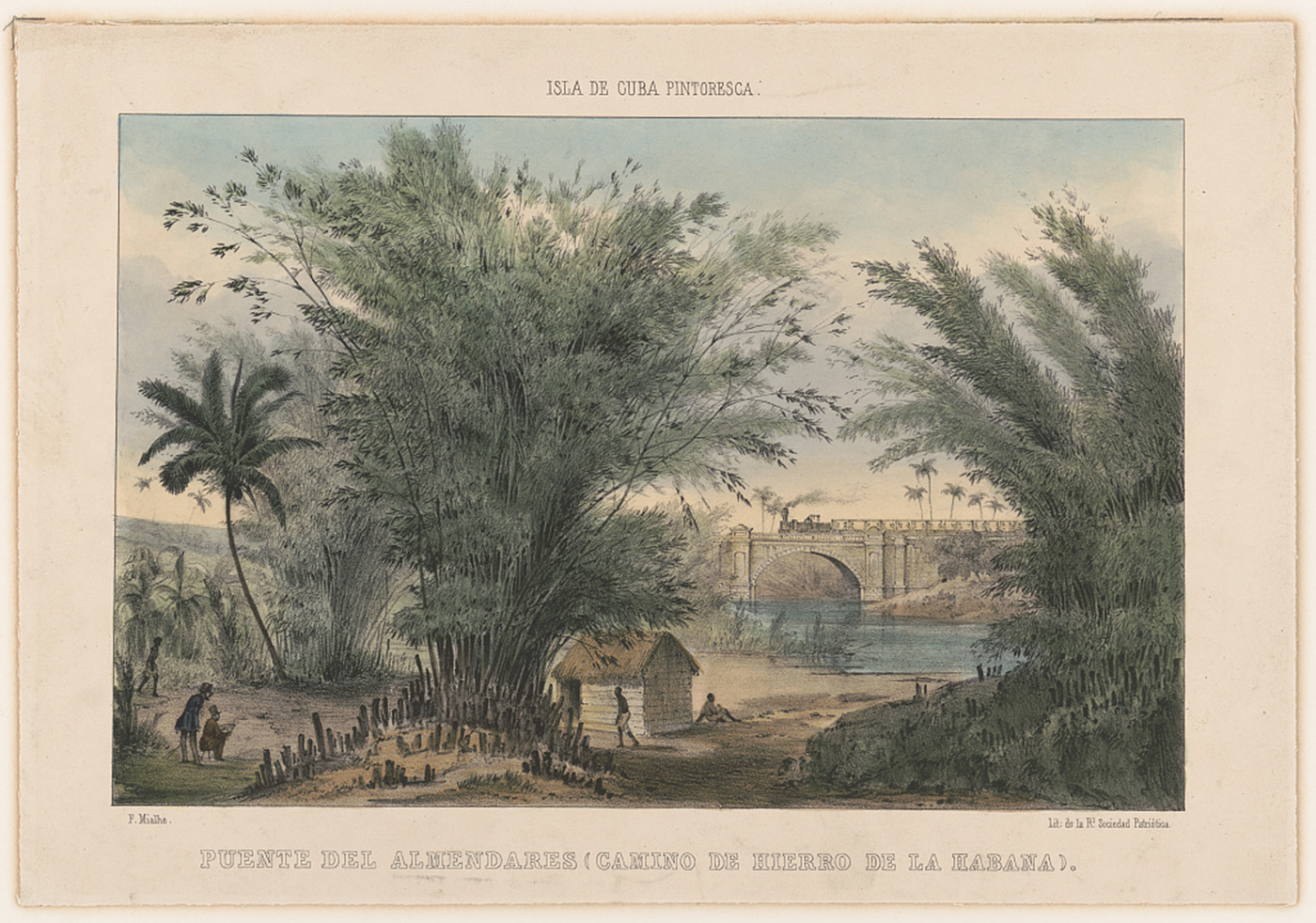

Figure 2. Railroad Bridge over the Almendares River near Havana.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C., USA.

CONCLUSION

This examination of forced labor in road and railroad construction reveals several insights about the state's use of coercion for public works to connect Havana's port with the rapidly expanding plantation sector in its hinterland. The vast majority of workers employed in infrastructure building in Cuba entered through the port of Havana as migrants under some form of coercion – enslavement, a prison term at hard labor, or, after 1800, an indenture contract. As the island's plantation boom took place parallel to the growing movement to abolish the transatlantic slave trade and slavery itself, for state officials the costs of purchasing enslaved workers rose prohibitively over much of the period from 1790–1838. State- or privately owned slaves were usually too valuable to be employed in large numbers in public works. Hence, Cuban elites and their state collaborators sought out other vulnerable groups who could be forced to do road and rail work at lower costs and under sufficient control to advance the projects.

Free householders successfully rebuffed those efforts. Convicts had little choice, but their numbers and lengths of sentence fluctuated widely. Captured fugitive slaves rarely provided years of labor for public projects, because they were often in poor health when captured and their owners were likely to reclaim them. State officials and Cuban planters had more success, forcing the unfortunate emancipados into both public works and plantation labor, because the anti-slave trade treaties allowed Cuban captains general to consign them for years of coerced labor, in spite of their nominally free status.

Ultimately, contract laborers provided the mix of low cost and unfreedom that both planters and state officials desired, after some experimentation. Unlike free workers, contract laborers’ resistance or desertion could result in arrest and return to work as a convict, but the racial hierarchy of a plantation society set both state and private employers’ expectations for necessary subservience. “Irish” workers, whose whiteness was initially seen as an asset, were ultimately deemed too disobedient and their recruitment was abandoned. Canary Islanders were white and Hispanophone and therefore too likely to successfully flee work sites.

These problems were outweighed in the short term as the contracted labor of North Americans and Europeans was the supplement to other forms of forced labor needed to establish the first rail connection between Havana's port and growing plantations to the south and east. However, after 1838, both planters and colonial officials sought a new group of racially and culturally different contract workers, especially from China, to supplement enslavement on plantations and on rail lines, as the fate of slavery in the Atlantic world became more uncertain. The railroad promoters’ problems and losses with white contract workers in the early 1830s led Cuban Captain General Alcoy in 1849 to petition the Crown for permission to use the tools of enslavement to control contracted workers from Yucatan and China – “the whip, shackles, and stocks”. Queen Isabella II agreed that such control was essential because without them “the subordination of the African race so indispensable for the tranquility of [Cuba] would be altered”.Footnote 70 The experiments with white contract workers showed state officials and planters that coerced labor without the controls allowed by enslavement were too risky in Cuba once the sugar boom and slavery dominated the island's economy and society.