In recent years, Brazilian labor history has shown how the study of urban, non-industrial activities provides us with a privileged vantage from which to consider the connections between economic relations, the social and occupational structure of cities, and the ways in which workers have intervened in political life. New studies of urban labor have contributed significantly to an effort to re-think both the range of research questions and the general explanatory framework through which we have considered workers’ experiences. This effort has been carried out through the intense analysis of a variety of types of primary sources and, at the same time, has gained theoretical and methodological inspiration from microhistory, from English social history, and, more recently, from international debates concerning the intersection of class, gender, and race.Footnote 1

This article focuses on the lives of workers in small commerce and in domestic service in nineteenth-century Rio de Janeiro, and thus it is indebted to the debate concerning the social history of urban labor in Brazil. At the same time, this study contributes to this debate by focusing on two types of workers who, although among the most ubiquitous in the city, have been overlooked as a source of insight on how urban laborers confronted the era’s transformations. Concentrating on Rio de Janeiro during the Brazilian post-independence period of constitutional monarchy known as the Empire (1822–1889), in which it functioned as the country’s capital, this article places at the center of its analysis a city that experienced the economic, sociopolitical, institutional, and legal changes that characterized both Brazil and the broader Atlantic world in the nineteenth century in an almost emblematic way. As the main commercial and political center of the country and a space for the circulation of people and goods that connected at least three continents, the city of Rio was a site of experimentation for legal and institutional innovations. Rio de Janeiro was one of the most important slave-holding cities in the Americas and also the destination of thousands of immigrants of various nationalities. Nineteenth-century Brazil’s capital city thus provides a privileged point of view from which to consider the changing urban social structure, as well as the ambiguous dividing lines between enslaved, dependent, and free labor, and the transformations to the social composition of the laboring classes.

Recent studies of social stratification in cities have primarily focused their attention on the lives and social and economic strategies of the intermediate social sectors, which fit poorly within the dichotomy so central to nineteenth-century Brazil between the propertied elites, on the one hand, and the enslaved persons subordinated to those elites on the other. Such studies demonstrate that the numerically significant presence of these workers in Brazilian cities has garnered far less scholarly attention than they deserved.Footnote 2 It was precisely from this heterogeneous social stratum, which consists of free men and women, freedpersons of African origin, and the Luso-Brazilian poor and working classes, in addition to foreign immigrants of various nationalities and legal statuses, that some of the century’s most important social actors in Brazilian political and social life emerged. These men and women made up the urban middle classes as well as a large part of the urban laboring sectors, which were the socioeconomic sectors best positioned to aspire to upward social mobility and most able to organize themselves to fight for the recognition of the dignity of their work and of their political rights.Footnote 3

At the fringes of this intermediary social group were those more or less impoverished (but not necessarily miserable) workers who were involved in a myriad of urban activities that were connected to the infrastructure that kept the city functioning. They were the less skilled civil construction workers, those who worked in various forms of urban transportation, the non-proprietary laborers in small commercial establishments, and the men and women involved in various types of domestic labor who were free, but often worked side by side with the enslaved.

This article seeks to understand both what united and differentiated one group of domestic laborers (female maids, or criadas), on the one hand, and one group of workers in small commerce (male clerks, or caixeiros) on the other, two types of non-enslaved laborers whose lives and work had much in common, and two categories of labor that are frequently overlooked in Brazilian labor history. We will consider what their divergent trajectories over the course of the nineteenth century can teach us about the shifting dynamics in labor relations in a society marked by both slavery and labor dependency more broadly. As sources for this analysis, we will draw on documents produced by legal proceedings from the 1830s through the 1880s in which men and women involved in petty commerce and domestic service presented their cases before the courts to claim their unpaid wages.

The principal objective here is to relate the ways in which, in the course of the nineteenth century, these workers’ experiences in “serving” both approximated and diverged from each other as they lived through the social processes that profoundly altered the history of labor in Brazil: the transformation of the legal paradigms that had been developing to regulate and organize contracts and commercial relationships; the imposition of new forms of control over urban labor; the slow decline and eventual abolition of slavery; and the social reconfiguration of the urban working classes and the means by which they might claim their rights.

CRIADAS AND CAIXEIROS IN THE EXPANSION OF URBAN SERVICES: UNSTABLE BOUNDARIES

The extraordinary development of the city of Rio de Janeiro in the first decades of the nineteenth century was marked by two politically fundamental events: first, the transfer of the Portuguese royal court to the colonial city in 1808; and second, the political independence of the colony and its transformation into the Brazilian Empire in 1822, with the city serving as the site of the nation’s capital and the headquarters of the royal court. Rio thus consolidated its role as the most important link connecting the country with Atlantic markets, which brought about an increase in commercial activity and allowed for an impressive accumulation of wealth.Footnote 4 Rio’s new-found economic strength affected urban life in many ways, but what interests us here, in particular, is the resulting expansion of consumption and the exponential growth of services and of all types of trade. The demand for a variegated labor force made the city a major center for the importation of both enslaved and contract immigrant workers, with profound consequences for its social dynamics.

Demographic data gives us a clear idea of the extent of the impact of this process on the city. Its population in 1821 was approximately 112,000, half of whom were enslaved. In 1849, around 110,000 enslaved workers lived in Rio de Janeiro’s parishes, out of a total population of approximately 226,000 inhabitants, a third of whom had been born in Africa.Footnote 5 Immigrant workers, primarily Portuguese ones, made up a considerable part of the remaining free population: in 1846, a representative of the Portuguese Crown estimated that between 20,000 and 30,000 of their compatriots lived in the city.Footnote 6 Among the poor free laborers, whether immigrants or native-born, a sizeable portion worked in either commerce or domestic service.

The proliferation of both caixeiros and criadas resulted from this same growing demand for urban services in nineteenth-century Rio de Janeiro. These two groups’ life experiences also converged in the particularities of their daily labor in private homes and commercial establishments, where work and life were elaborately intertwined. Most of these individuals resided in the homes and commercial establishments in which they worked, having neither accommodation of their own, nor any defined work schedule, carrying out an innumerable array of subaltern tasks. These two categories of workers thus shared a high level of domesticity and participation in the lives of their employers, with various levels of intimacy, and, relatedly, few opportunities for privacy and time to attend to their personal lives. This characteristic of their work and personal lives was intensified by the fact that both caixeiros and criadas were often recruited from the ranks of the city’s youth, who had dependent relationships with and sometimes even family ties to their bosses.Footnote 7 The particular type of dependency that characterized these relationships was sometimes reflected in the forms of remuneration that they were offered for their work, where it was difficult to draw a clear line between an employer’s obligation to provide training and sustenance on the one hand, and payment for services rendered on the other.

Criado and caixeiro do not describe stable and well-defined occupations and statuses inside private homes or businesses. Each of these words is a superficially straightforward, but essentially untranslatable term that denote a common occupation in nineteenth-century Rio; in English they roughly translate as, respectively, “maid” and “clerk”. Yet, as this article will show, the words criado and caixeiro carry with them a cloud of contextual assumptions that make these terms, themselves, precious historical artifacts. For this reason, they appear throughout this article in their original Portuguese form.Footnote 8 The levels of responsibility and trust that these laborers enjoyed, as well as the type of activities they carried out, shaped hierarchical relationships within the workplace, which, in turn, were reflected in their levels of autonomy and their expectations concerning their remuneration. These hierarchies also grew out of discrimination based on gender, skin color, age and nationality, and they occupied a central place in these workers’ lives. The problem of confronting these hierarchies was made even more dramatic for Rio’s workers because they lived in a society where most manual labor was, in fact, carried out by enslaved persons, who were expected to be submissive and subservient.

This overview of the relative position of criadas and caixeiros gives us a useful point of departure, but it is not sufficient to elucidate either the specificities of the work and pay arrangements that involved these two categories of workers, or the tensions that beset their daily lives. In the pages to follow, we will thus subject a selection of legal cases involving labor arrangements worked out within private homes and businesses to detailed analysis, allowing us a closer view of the transformations these types of workers experienced and their relationship to the law over the course of the nineteenth century.

Figure 1 Map of Rio de Janeiro.

One of these legal cases is from April 1833, when Jacintho Almeida sued his former employer, Francisco da Costa, for wages he had never received. According to Almeida, his boss owed him for the final three years during which he had worked in Costa’s small grocery store in Rio de Janeiro’s port district.Footnote 9 Almeida further explained that he had only received part of his total annual wages of 300$000 réis,Footnote 10 and that his former boss owed him a debt of 758$620 réis, the payment of which he sought in court.

In his own version of the facts, Costa affirmed having put the management of his grocery store in Almeida’s hands not just as a simple caixeiro, but instead as a “true administrator” (administrador) when he left for Portugal in May 1831. Costa may have made this trip to avoid the effects of the resurgence of anti-Portuguese sentiments that marked that year. These conflicts dealt a powerful blow to the Portuguese small business owners who dominated Rio’s petty commerce and provided most of the few work opportunities available for the city’s free poor.Footnote 11 In his testimony, Costa not only stated that he owed nothing to Almeida, but he also asserted that, when returning to Rio in 1833 and taking an inventory of his store, he discovered that, in his absence, his former employee had sold merchandise on credit without his permission. Worse still, he claimed that Almeida “came to enjoy [his] establishment, taking from it both merchandise and money, and in this way Almeida was able to set up his brother with his own small shop, which was probably just a front for selling Costa’s [stolen] merchandise, because neither [Almeida, nor his brother] had anything of their own.”Footnote 12 He therefore refused to engage in any negotiation with Almeida concerning his delayed wages as long as his former caixeiro failed to “produce an exact accounting of the business”.

Among the witnesses called to testify were other shop employees and owners of small businesses established on nearby streets. All attested to the trusting relationship between Costa and his primary shop employee before Costa’s trip. Witnesses on both sides also affirmed the difficulty of establishing the kind of commitment that existed between a boss and an employee, providing information that corroborated the two conflicting versions of the dispute. On the one hand, Almeida argued that he had been Costa’s caixeiro, and therefore his employee and subordinate, who should be payed a wage (soldada).Footnote 13 On the other hand, Costa affirmed that he had placed Almeida in the position of “administrator”, but that Almeida had not carried out his obligations in accordance with that position. In his line of argumentation, which was ultimately successful in winning this case, Almeida’s attorney recurred to the Philippine Ordinances (Ordenações Filipinas), a compilation of Portuguese laws that had been in effect since the end of the sixteenth century and continued to be used in independent Brazil until the first decade of the twentieth century. The argument directly cited the conditions under which bosses could demand reparations for damages done by criados to their amos (a word that means “master”, without necessarily implying that the subordinate person is a slave), affirming, in Almeida’s case, not just that the “damage” had not been proven, but also that the demand had been made too late to have had any legal effect.Footnote 14

Almeida won his case before the trial court judge, a decision that was later confirmed by the final judgment (acórdão) rendered by the panel of magistrates of the appellate court (Tribunal da Relação do Rio de Janeiro). The judges ruled that Costa, the employer, had never established the terms under which Almeida should carry out the administration of his business affairs, which reinforced Almeida’s position as caixeiro rather than as an actual business partner. In basing his legal defense on the difference between an “administrator” and a “caixeiro”, Costa made a distinction that the law did not recognize and followed a model of commercial law that would only be established in Brazil two decades later. The provisions in the Philippine Ordinances that required the boss to provide evidence of any complaint against subordinate workers and to prove that he did not owe them wages, ultimately strengthened Almeida’s case. The relationship between Jacintho de Almeida and José da Costa certainly did not represent the average labor dispute that developed in many businesses in Rio de Janeiro. In this particular case, there was an evident level of proximity and trust between the caixeiro and his employer, and Almeida’s position as the “first caixeiro” and eventual administrator of his boss’s business placed him in a privileged position to negotiate his wages. Disputes involving subaltern caixeiros only rarely found their way into the courts and were seldom as well received when they did.

An eloquent contrast with the case brought by Almeida can be found in a civil case that took place at a similar time in the courts of Rio de Janeiro, involving Francisca de Azevedo, a white woman from the neighboring state of Minas Gerais. In 1835, she presented a “compensation suit” (ação de soldadas) against the assets of her former employer, Valentim dos Santos. Santos was the owner of a commercial enterprise near the Valongo quay, a central area next to the city’s port. His activities certainly placed him in a high social position, since his business served as the depository for the city’s judicial courts.Footnote 15 According to Francisca, she had been employed in Valentim’s shop and in his home as a criada since “more than twenty years ago, taking care of his house, overseeing the slaves, and carrying out all of the tasks inside the house that are the proper work of criada”.Footnote 16 Since they had not made any specific agreement about her wages, she expected that her accumulated earnings would be paid to her once her services were no longer needed, as was customary in Rio de Janeiro. When her boss died without leaving a will or an account of his assets, Francisca sought recourse in the justice system, requesting the payment of her overdue wages, which she determined to be the modest sum of 12$000 réis per month.

Damazo Pacheco, the executor of Valentim Santos’s will, argued that Francisca de Azevedo had never been his criada, but rather his concubine for twenty years; she had been, Santos stated, teúda e manteúda, a typical expression of the day that unmistakably alluded to a consensual but highly asymmetrical sexual relationship outside of wedlock, “a kept woman”. To prove his argument, Pacheco affirmed that Francisca, during the time when she lived in the General Depository (Depósito Geral), had built up her own business by selling groceries and even acquiring her own slaves to that end. Furthermore, according to Pacheco and several of the witnesses he called to testify about the relationship between the two, Valentim and Francisca had such a close, personal relationship that he entrusted her with the task of managing his paperwork and promissory notes. In one of his most striking arguments, Pacheco’s lawyer insisted that he could only imagine Francisca as Valentim Santos’s lover, given her role in his house and store: “Because it is not customary in this city to put pretty, young white women into service in the kitchen and the living room [...]; [they are], conventionally, limited to being a concubine and to being well treated.”Footnote 17

Francisca never accepted the version of this story that portrayed her as her boss’s lover, nor did she admit in the court documents to having had any relationship with him that did not derive from her position as a criada da casa, a domestic servant. She was, nonetheless, unable to prove her case either through documentary evidence, or by offering witness testimony attesting to the fact that she had been employed by Valentim, or that she had made some arrangement with him concerning her remuneration. Francisca lost the case; the judge denied her demand for her back pay.

By closely examining those details of the case on which both Francisca de Azevedo and the witnesses agreed, however, we can extract a great deal of information both about her daily work life and the ambiguous space she occupied within Valentim dos Santos’s house and store where her employer lived and conducted his business. The “General Warehouse labyrinth”Footnote 18 was how Francisca’s lawyer, Antônio Picanço, described this space where the boundaries between house and place of business were impossible to establish. Francisca gave orders to the many household slaves charged with maintaining her employer’s home, attended to the needs of the clerks who worked in her boss’s store, as well as bearing direct responsibility for Valentim’s documents. She also appears to have taken care of the enslaved workers who remained in the General Warehouse pending the resolution of legal disputes over them, and their masters appear to have paid her for this task. Just as significantly, Francisca also attended personally to Valentim, even caring for him when he became ill.

The difficulties in defining the limits between criada and senhora (mistress) – in the vocabulary used by the witnesses to describe the ties between Francisca and Valentim’s household – leave no doubt that she was essential to the day-to-day functioning of the warehouse, whether as a dwelling or as a business. Yet, Francisca did not demand her wages as a shop caixeira, but rather as a personal criada. Because of the evident social difference between boss and employee, it is unlikely that anyone would have believed them to be business partners. Francisca herself presented the fact that she did business at the fringes of the operation of the warehouse making and selling food as evidence of her boss’s “liberal” nature and not as proof of her independence. In asking for “payment” as Valentim’s criada, she used the legal language available to describe a complex relationship. This relationship involved not only work, but also the intimacy of close coexistence for over two decades and the mutual trust in conducting daily household and business affairs. Although the justice system did not agree with her vision of the facts, Francisca nonetheless had no doubt that hers was a relationship that merited compensation for services rendered.

The cases of the caixeiro Jacintho Almeida and of the criada Francisca de Azevedo raise numerous questions that cannot be explored in detail here, but their stories illuminate the contradictory situations that could arise in places of business and in homes in Rio de Janeiro in the 1830s. The contrast between the outcomes of these two cases is striking, as are the differences between what the parties in each case felt they needed to bring to light before the court. We learn little about the personal relationship between Almeida and his former boss, since the lawyers in this case only saw fit to present evidence concerning Almeida’s wages and witnesses’ testimony about the nature of the two men’s business relations. By contrast, the other case contains both abundant information concerning the roles that Francisca played in her boss’s life and often contradictory references to the real or alleged intimacy between her and Valentim. Both Jacintho and Francisca held central importance in the daily operation of their respective bosses’ homes and businesses, and both held publically recognized responsibilities. Yet, the ways in which these cases were presented, argued, and adjudicated could not have been more different.

Jacintho and Francisca fought for their wages, which should have been paid to them for their work, dedication, and trustworthiness. These two litigants, however, were confronted with different strategies to deny them what they sought. Costa, Jacintho Almeida’s boss, attempted to prove that Jacintho was not just any employee, but rather was someone whose position as an “administrator” imposed responsibilities that were not met. Therefore, he argued, Jacintho was not owed wages. Unable to prove his accusations, Costa was obliged to pay the wages due to Almeida. Francisca was met with entirely different arguments to counter her demands: she was forced to defend her position within her boss’s home against attacks that called into question her morality. Her boss’s trust in her ability to carry out her tasks, instead of having served as proof of her qualities as a worker, were used to attest to the type of intimacy that was judged incompatible with remunerated labor. In a slave society in which subaltern work was powerfully racialized, even Francisca’s skin color was used as evidence against her; her “whiteness” indicated that she was not sufficiently subaltern to have been considered a paid domestic worker. As a laborer, Francisca was disqualified from being Valentim’s business partner or his employee; as a woman, her connection with the household had not been formalized by marriage. Thus, the only possible place left for her in Valentim’s home was that of a concubine, a position that neither conferred any rights on her except the generosity of her protector, nor gave her any grounds for demanding compensation as a “true” criada.

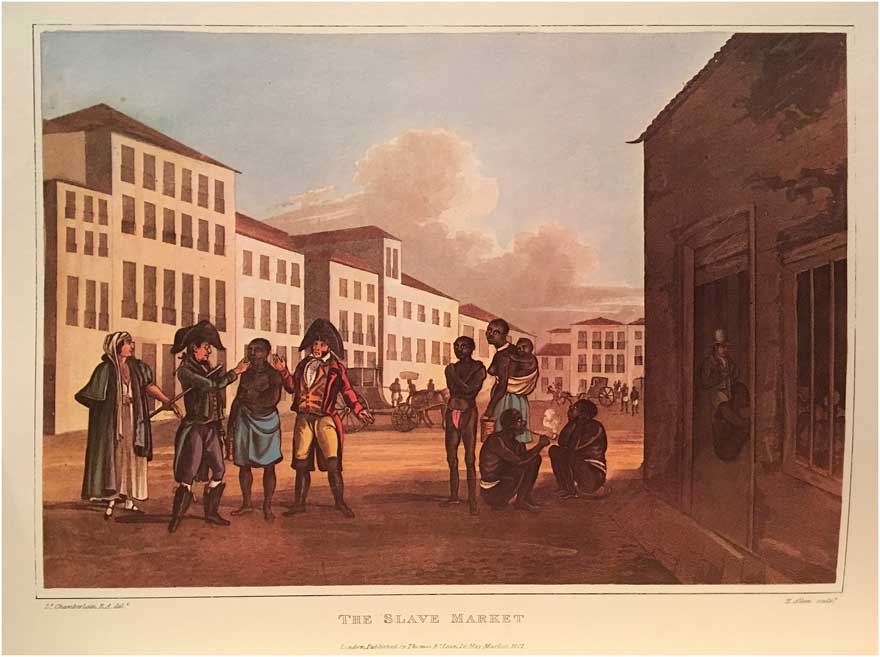

Figure 2 This plate, entitled “Slave Market” was originally painted by the British officer Henry Chamberlain (1796–1843), who visited Rio de Janeiro in 1819 and 1820. It depicts the surroundings of the Valongo, the famous docks were the Africans who survived the Middle Passage were sold in the markets as slaves. Around the commercial area of the Valongo and Rio’s waterfront, many of the stories discussed in this article unfolded. Chamberlain’s description reads: “The Plate represents an elderly Brazilian examining the Teeth of a Negress previous to purchase, whilst the Dealer, a Cigano, is vehemently exercising his oratory in praise of her perfections. The Woman looking on is the Purchaser’s Servant Maid, who is most frequently consulted on such occasions.” Views and Costumes of the City and Neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, from Drawings taken by Lieutenant Chamberlain, Royal Artillery, during the years 1819 and 1820, with descriptive explanations (London, 1822).

THE ARBITRARINESS OF THE LAW AND VULNERABILITY: HOW CAN ONE PROVE LABOR?

The legal actions described here so far were initiated at the beginning of the 1830s, a decade that witnessed the consolidation of political and legal institutions that formed the contours of the monarchy in post-independence Brazil. Among the legal transformations during the period after the passing of a constitution that was considered to be liberal (1824), Brazil also passed the first of a series of laws aimed at making the Atlantic slave trade illegal in 1831, as well as the promulgation of the Criminal Code (1830) and the Code of Criminal Procedure (1832). More specific legislation was introduced establishing the legal basis for labor contracts for free urban and rural workers in 1830 and 1837. These laws regulating “service rental” were, above all, motivated by the widespread anxiety among planters, still profoundly dependent on slavery, about the supply of available farm labor. It is no coincidence that, in the 1830s, the number of immigrants also increased exponentially, especially those coming from Portugal, who established themselves not only in rural areas, but above all in Brazil’s major cities, where they had to compete with and find a space among other poor, free, or freed workers.Footnote 19

These transformations in the legal context only partially affected the labor disputes discussed here. These laws had no measureable effect on the proximity and, indeed, the overlapping nature of caixeiros’ and criadas’ work; nor did these codes and statutes passed in the 1830s and 1840s, mitigate the ambiguity that marked caixeiros’ and criadas’ laboring lives, which had for centuries been codified in the Philippine Ordinances still being cited in the cases examined in this article. The Ordinances established the conditions under which one could request wages for services rendered as a criado, a generic category that could have included caixeiros.Footnote 20 The legal uncertainty about how to treat these categories of workers persisted throughout much of the nineteenth century, even with the restructuring of the legal institutions and paradigms that shaped the administration of justice in post-independence Brazil. In the three versions of the laws promulgated to regulate the “service rental contracts” (contratos de locação de serviços) for free persons, passed in 1830, 1837, and 1879, there were no references either to the work of caixeiros or of criados.Footnote 21 This interest in regulation was, above all, the product of anxieties about the labor supply and was part of the process of seeking alternatives to slave labor. The continuity of Brazil’s socioeconomic system that depended on captive labor was under threat due to the attempts to abolish the Atlantic slave trade (which had been legally challenged since 1831, until it was finally abolished in 1850)Footnote 22 and to widespread expectations that slavery was about to end (which would only occur in 1888). Initially conceived in the context of this substitution of free for enslaved labor, above all on farms, the laws regulating “service rental” ended up indirectly providing a legal horizon that was also applicable, theoretically, to urban labor, even though the legislation did not touch on wage labor relations that potentially involved caixeiros or criadas.

It was not, however, the letter of the law that decided on the duties, rights, and limitations that applied to caixeiros and criadas, but rather, social and legal practices influenced the decisions and the differential results that each legal case produced. One can argue that this legal ambiguity implied that judicial cases involving unpaid wages proceeded in a particularly arbitrary manner, especially those whose results might have been influenced – directly or indirectly – by the litigants’ gender, skin color, or nationality.

Another example of this legal ambiguity put into practice can be found in a case initiated in the Third Civil District (3ª Vara Cível) of Rio de Janeiro in 1842. On 25 May of that year, the lawyer Antonio Carneiro da Cunha, as legal representative of Francisca do Sacramento, filed a complaint demanding the payment of wages for work that had been carried out but never remunerated.Footnote 23 By way of her attorney, Francisca affirmed that on 1 September 1823 she had moved into the small grocery store (casa de quitanda) that José da Silva had established that year on a square called the Largo de Santa Rita, to “serve him receiving a salary of ten thousand per month”. She continued working for Silva until his death on 2 April 1842. According to Francisca, in the nearly nineteen years during which she had worked in that house, she had never received “even one single real in wages” and Silva had died without having settled his debt to her.

Both José and Francisca were identified as “freed blacks” (pretos forros), indicating their past as enslaved persons. Three witnesses were called for Francisca to testify about the nature of her professional relations with Silva. Summoned to speak of Francisca’s honesty, the witnesses described her in the following manner: a “rustic black woman, very hardworking and God-fearing [...] incapable of asking for what is not rightly hers”. No one came forward to contest these witnesses’ accounts of Francisca’s character, and through them we can understand something about the importance of Francisca’s work for her boss’s business.Footnote 24 The testimony reveals that, from 1835 on, Francisca also worked in another business that Silva opened on the same street, the Rua do Valongo, which sold roasted coffee beans. This was a lucrative operation, and all of the witnesses in this case attributed Silva’s financial success to this new business. According to Joaquim de Seixas, a forty-eight-year-old artisan who lived in the center of the city on the Rua do Sabão, Francisca’s work involved activities inside the two places, but in this second store in Valongo, she “also occupied herself doing manual labor in addition to working in the kitchen, due to the fact that the most important part of this store was the sale of roasted coffee, which, because of the excellent way in which it was prepared, was in high demand among buyers”, and it was, in fact, Francisca “who ground the coffee as well as operating the roaster, with whose business the late owner [Silva] had acquired a sufficient livelihood, and in fact a real fortune”. Another witness, Xavier de Oliveira, was a man of more than fifty years of age of African descent but born in Rio de Janeiro, who sustained himself by working for the Ordem Terceira de São Domingos, a Catholic religious order. Oliveira confirmed that Francisca do Sacramento had worked as a caixeira, also “carrying out all types of work inside the house” where she lived and “rented” out her services and, above all, had worked on the Rua do Valongo “where she was continually grinding roasted coffee”. Finally, José da Fonseca, a twenty-eight-year-old white man and a business owner and neighbor of Silva’s with whom he was said to have made “commercial deals”, recalled that six years earlier he had asked the late Silva why he had not purchased a slave, “given the great amount of work he always required”. According to Fonseca, Silva’s response was that he “had rented [Francisca] for a long time, and that it made the most business sense to have her as such, rather than to buy a slave and run the risk of losing her, and that in addition to that he was very used to the work that she did”. At least implicitly, all of the witnesses appear to corroborate the statement that had been made in her petition to the court: “everything that [the late Silva] had acquired in his life” had been “at the cost” of Francisca’s labor.

The trustee appointed by the court to oversee the distribution of the freedman José da Silva’s inheritance did not call any witnesses to contest the facts presented by Francisca do Sacramento. Indeed, he even resisted responding to the official summons calling for arbitration to determine her wages, only asking his attorney, Caetano Alberto Soares, briefly to contest the validity of the entire procedure. Soares wrote his response to this request directly on the pages of the official court documents, in which he delegitimized Francisca’s demand, saying that she had not “proven any one of the points in her lawsuit”: neither the time that she had served, nor the price that she had arranged, nor even whether she had, in fact, performed any service for him at all. Once again, to build his case, Soares drew on the articles in the Philippine Ordinances that dealt with the conditions for paying criados.Footnote 25 With no written contract, and with nothing written in Silva’s will that might confirm his debt to Francisca, Soares did not even bother to call the witnesses’ validity into question, simply requesting that the court “not allow the estate to be held in abeyance” – in other words, that the court prevent the late Silva’s property from becoming available to creditors.Footnote 26

The lower court judge deciding this case summoned appraisers to arbitrate the wages owed to Francisca do Sacramento, and both agreed on a requested monthly sum of 10$000 réis, a modest amount of money. In his written decision, the judge affirmed that the facts presented by the witnesses had proven the case, awarding her a total of two contos and 230$,000 réis. The trustee of the estate, however, appealed the case to the Tribunal da Relação do Rio de Janeiro, where the appellate court judge (desembargador) Francisco de Campos overturned the decision. Campos considered the entire case, in his words, as “irremediable invalidity”, since it had not been sent to the Juizado de Órfãos, the special court dedicated to the adjudication of family matters, and, according to this judge, the appropriate forum for disputes concerning post-mortem property inventories. Judging null and void the entire case because of this technicality, he ordered Francisca to pay the costs of the judicial procedings.Footnote 27

We know no further details of this story other than those found in the petition that was submitted to the court in Francisca do Sacramento’s name. The outcome here was similar to that suffered by other poor women who tried their luck in court requesting the unpaid wages that they had earned as criadas. Like Francisca, other women not only had their pleas denied, but also had to shoulder the financial burden of having dared to bring their cases to court and being ordered to pay the costs of their court proceedings.Footnote 28 Gender and skin color certainly played a role in these cases, although these factors do not appear explicitly in the official court documents. Francisca’s vulnerability becomes visible, however, as this case unfolds. First, it is revealed in the basic fact of her subaltern position. Multiple witnesses’ descriptions of Francisca as a “rustic” and uncultured woman, although uttered with discernable tones of condescension and undoubtedly colored with class and racial prejudice, allow us a glimpse of her genuine state of destitution. Second, it is apparent in the difficulties she experienced in trying to represent herself legally; as a woman, as a freedperson, and as someone who was illiterate, any access she had to the law depended on such male intermediaries as Manoel Pereira, the solicitor (solicitador de causas) whom she initially sought out to bring her case to court, or Antônio Carneiro da Cunha, the modest attorney who unsuccessfully presented her case to the appellate judge. Neither of these men showed themselves able to confront the opponent representing the other side of this case, Doutor Caetano Alberto Soares, a distinguished member of the capital city’s judicial elite. The following year, Soares would be one of the founders of the Brazilian Institute of Lawyers, an important national professional organization.Footnote 29

Caixeira was how Francisca do Sacramento’s witnesses described the position that she occupied in João José da Silva’s store. Under this label, however, fell an extensive set of responsibilities that included the care of Silva’s home and his store, a range of kitchen duties, and other forms of “manual labor”, menial tasks that under other circumstances at least one witness considered could have been carried out by a domestic slave. This description of her role as a caixeira effectively erases the limits between household tasks, on the one hand, and those to be carried out in public on the other: in other words, the limits between the supposedly reproductive activities carried out in the domestic sphere and the productive, commercial activities that defined the operation of a small coffee roasting and sales business.

NEITHER CAIXEIRA, NOR CRIADA: THE LEGAL LIMBO OF FEMALE LABOR

Payment agreements that went unfulfilled provided both male and female workers with the rare opportunity to express to judicial authorities their expectations about how their labor should be treated and remunerated. In a world where the notion of work as a source of specific rights had yet to take root, these judicial conflicts raised expectations about rights that the law, in general, rarely even contemplated.

As the cases that this article has presented so far demonstrate, despite the existence of a few juridical positions taken concerning caixeiros and of laws governing “service rental”, the juridical language employed in disputes over the wages of caixeiros and criadas still came exclusively from the centuries-old “Philippine” Luso-Brazilian body of laws.

The great legal innovation that had the potential to change this situation was the Commercial Code of the Empire (Código Comercial do Império), which became law in June 1850.Footnote 30 This code established the legal parameters for the exercise of commercial activity in the country. The Commercial Code did not directly address the conditions of wage laborers, but, in its article 226, it defined a broad range of commercial leasing, which included the rental of “something” or of a person’s labor, for a specific amount of time and price. Thus, what this law covered was piecework and not, properly speaking, wage labor. In November of that same year, however, the introduction of the Procedural Commercial Code included, within the realm of commercial law, “questions concerning the setting of payments, and of wages, rights, obligations, [and] responsibilities of auxiliary commercial agents”.Footnote 31 Thus, at least theoretically, disputes involving caixeiros who, to the degree that their “persons and acts” could be defined as strictly commercial, now fell within the purview of Brazilian national commercial law.

The legal foundation of labor contracts in general, and above all those in Brazil, remained the object of controversy, as a query made by the Emperor to the Justice Section of the Council of State in 1860 suggests.Footnote 32 In their officially published response to the question about which legislation was in force to regulate the work performed by Brazilian (as opposed to immigrant) laborers, the Council pointed to the Commercial Code of the Empire. Domestic labor was, however, explicitly left out.Footnote 33

There is no doubt that the passing of the Code intensified the distinction between the work of caixeiros and that of other types of workers before the law. The Code required that “owners of businesses in any kind of commerce”, maintain “uniform order in accounting and bookkeeping, and have books for these necessary purposes”.Footnote 34 This provision accentuated the formalization of caixeiros’ labor arrangements, to the extent that it was expected that wages and money paid and owed would be registered in the accounting books. Thus, the Commercial Code had the effect of reinforcing the contractual character of labor relations in wholesale and retail stores, favoring formalized relations to the detriment of the informal and sometimes familial arrangements that were so common both in domestic labor and in the relationships between bosses and their apprentices in commercial establishments.

Once again, the letter of the law did not directly discriminate with respect to the sex of the workers, and it would, at least in theory, have been possible to imagine the existence of women in the ranks of the caixeiros. Yet, as the cases of Francisca de Azevedo and Francisca do Sacramento in the preceding decades already signaled, it was not so easy to establish clear boundaries between the work assigned to criados and that of caixeiros, much less in the case of a woman. And for those women whose work was simultaneously domestic and commercial, the difficulty of proving an employment relationship shows that theirs was a type of domesticity that the law and its agents failed to recognize as a source of rights.

Thus, it is not surprising that, after 1850, all of the judicial cases in Rio de Janeiro that included the demand for the payment of wages on the part of caixeiros, who were invariably male, were only heard in the Commercial Court. Similar demands for wages made by women presenting themselves as criadas, for their part, were still directed to the Civil Court Judge (Juízo Civil), a jurisdiction that continued to function according to a body of laws that remained contaminated by the same legal ambiguity which had characterized the earlier decades. The last case we will analyze powerfully reveals how the legal ambiguities confronted by women who worked in homes and commercial establishments persisted in the following decades, a period marked by major socio-political transformations.

In May 1878, by way of a solicitor named Antônio Carvalho Guimarães, Anna Maria de Jesus presented a petition to the Judge of the First Civil District of Rio de Janeiro, to force her former boss, José Gonçalves Maia, to pay a debt of back pay she said was owed to her.Footnote 35 Anna affirmed that she had been José Maia’s criada since October 1870, when she was invited to live and work as a servant in his home in Rio’s Santa Teresa neighborhood, where he also operated a small tavern in the same building. She worked there until 14 February 1878 when, dissatisfied with her job, she decided to collect the money owed to her. Anna affirmed that, in the seven years during which she had worked for José, he had never paid her any wages, which she calculated as amounting to a sum of 30$000 réis per month.

In the year in which she brought her case to court, Anna was fifty-two years old and José was thirty-two. Both were Portuguese immigrants of limited means, who had gone to Rio de Janeiro to make a life for themselves. José Maia, following the example of the many other young immigrants who were his compatriots, was a subaltern caixeiro working for other Portuguese shopkeepers before he was able to save enough money to acquire an establishment of his own. Anna worked as a wage-earning maid in a familial household. Once José had accumulated enough money to buy what the archival documents describe as an “insignificant tavern”, he invited Anna to join him there. Despite the modest accommodation – the structure was no more than a “shack made of wooden slabs and zinc” – Anna accepted the offer, perhaps seeing it as an opportunity to have a more independent life and work arrangement. At a certain moment during this period, Anna not only worked in his home and his tavern, but she also shared “a common bed” with José. From the moment when they began to live together, despite their obvious proximity, the parallel lives of these two Portuguese immigrants began to diverge in important respects. José Maia had opened his business as a small tavern, but a few years later he was able to acquire another similar establishment, in addition to other real estate in the Santa Teresa neighborhood. And in May 1878, José got married, but not to Anna. By then, he had trodden the well-worn path traveled by many young Portuguese immigrants in Rio de Janeiro: ascending the social ladder by working in petty commerce, going from being caixeiro to being a boss.

While living under the same roof as José, however, Anna’s life took a different turn. The various witnesses in this legal case agreed that her work had extended to all aspects of José Maia’s life and business: she performed housekeeping tasks and cooked, as well as washing and ironing his clothes and those of his shop employees. In his taverns, she cooked, carried firewood, and made deliveries, and she sometimes oversaw the work of his caixeiros. Finally, she also raised animals on a small scale and provided services for other people, cleaning, cooking, and taking care of clothing for young, unmarried men, and in this manner she was able to put aside some extra money. The more José prospered, the more intense Anna’s workload became. When she decided to leave José’s home, the man for whom she was, in her own words, a criada, her decision was based on the excessive work, which was ruining her health. She was, she said, “disgusted” with the excess of tasks for which she was responsible, and she resented José’s decision to marry. At the time she presented her case, she had fallen ill and was interned in the Hospital da Ordem do Carmo, a charity hospital that was part of a Catholic religious order with which she was associated. She did not appear to have many resources and, in addition to the wages she never received, she also demanded that José Maia return the money she had loaned to him – money that she had been able to save from earnings from her work “outside”.

The dispute around this case was intense, carrying it to the appellate court. Although she did not deny her sexual relationship with José during the time when she worked in his home, Anna argued that her recognized personal sacrifice from when she worked in both his home and his businesses had conferred on her certain rights, which had not been respected. Although she had labored without making a previous arrangement for receiving wages, she was convinced that her efforts merited compensation since, in her lawyer’s words, “to work without pay is against justice”. But the response from José Maia and his lawyers contested the logic of the entire case, which, they said, was “unproven” and groundless and constituted a “false, imaginary, and impertinent story”. The nature of the relationship between José and Anna was at the center of the argument:

Because the plaintiff and the defendant cohabited, she as his lover, [...]; she gave orders to his caixeiros, raised chickens, sold eggs, washed and pressed clothes, provided food for his customers, [...], but all of this on her own account and without the defendant having received for himself any payment for these small jobs – she did not carry out, in the end, the work of a paid criada for the defendant but rather only those [tasks] compatible with communion between her and the defendant, compensated for with a roof over her head, food, friendship, a shared bed, and caresses.Footnote 36

José Maia’s formal reply to Anna’s petition to the court left no doubt about the extent of Anna’s activities and the diligence with which she had carried them out, or even the fact that on more than one occasion she had lent José money. What he contested, however, was the significance of these activities and her description of them as “work” that deserved remuneration. In the “communion” that constituted a relationship with a concubine, the question of its morality aside, there was no place for monetary compensation, since it was a voluntary relationship between two parties founded on an entirely different type of compensation. If Anna actually carried out all of the activities she described, she had done so out of gratitude for being José’s “dependent” and his “lover”, compensating him with her work in exchange for medical treatment and the other forms of care that he provided. Finally, in another strategy that he used to argue this case, José also tried to delegitimize Anna’s demands by questioning her case’s standing in that court. Since Anna was a foreign national demanding wages, she should have pursued her case before the Justice of the Peace (Juiz de Paz) and not in the civil court, according to the legal guidelines laid out in legislation passed in 1837, which dealt with the rental of the services of foreign workers.Footnote 37

Witnesses on both sides of this case corroborated the extensive range of tasks that were part of Anna’s work, although the doubt concerning whether she was in fact a criada or a amásia (lover) appeared, to most of the parties involved, to be an especially difficult question to resolve. The Judge of the First Civil District of the city, Caetano Andrade Pinto, analyzed the case in an exceptionally long, seven-page decision. After carefully describing the arguments one by one, his decision began by contesting the validity of applying laws that regulate service rental of foreign workers to questions related to domestic service, affirming his jurisdiction over this case. He proceeded by stating that he did not see any contradiction between the fact that the plaintiff in this case was both “the defendant’s lover” and his criada. Thus, if Anna “performed her own services [...] as a criada and not as a lover”, she would have the right to compensation for her work, “being that”, the judge continued, “the law does not recognize the communion resulting from a romantic relationship as having the civil effect of formal marriage uniting the couple’s property, and in this latter case [the defendant] would have to share this joint married property with the plaintiff; not even the fact of not having agreed upon the price of rental [of her services] takes away from the plaintiff the right to have her work paid at the price that shall be [determined by the court].”Footnote 38

Andrade Pinto only partially awarded Anna what she sought in this case, taking into account the lack of a written agreement concerning her wages and the fact that José was poor and “allowed her time to perform other types of service [outside his home]”. Both parties appealed the decision, and the case was then brought to the appellate court, the Tribunal da Relação. In December 1879, after reviewing the case, citing a lack of proof, the judge Luis Carlos de Paiva Teixeira decided against Anna’s demand for unpaid wage and, in addition, ordered her to pay the legal costs that the state had incurred. She unsuccessfully attempted to stay the decision, and the case was closed.

In light of the cases discussed above that had unfolded in previous decades, the outcome of this long process of litigation between Anna and José Maia is not surprising. The lack of a legal framework that made it possible to recognize unequivocally the labor relationship between these two people exacerbated the arbitrary nature of the judicial decision for this case. Once again, personal details concerning both parties abounded throughout the legal battle, as did the moral debate on the nature of their relationship. One of the elements of this ambiguity was precisely the difficulty of establishing with any precision which body of laws could provide the foundation for a judicial decision. The Philippine Ordinances were not directly cited, nor is there any mention of the Commercial Code. Laws regulating service rentals are mentioned, but the judges never actually considered them. In the lower courts, the case was decided favorably for Anna, but the decision makes no mention of any particular statute. The basis for the lower-court judge’s decision points toward a contrast that Brazilian law in the nineteenth century did not recognize: that a concubine relationship was not the same as a marriage and did not produce the “civil effect of formal marriage uniting the couple’s property”, and that must therefore be treated as a work relationship like any other. The appellate judge disagreed with this interpretation and dismissed the case rather than even rendering a decision on it.

Women who worked in Rio’s small commercial establishments and brought lawsuits demanding their unpaid wages only stood a chance of winning if they could present material evidence. They bore the burden of proof, a demand that was often impossible to meet. The expectation that a wage labor relationship could be proven by written documentation was at the center of these suits. As Brazil experienced a series of legal transformations over the course of the mid-nineteenth century, this expectation only gained importance in determining the outcome of similar legal disputes. The Commercial Code was only one of the laws that reinforced this dependency on written evidence and, therefore, on the public registry of contracts: a growing demand in commercial and civil relationships, but one that directly contrasted with the characteristic informality of domestic labor arrangements of that period.

If we think of these legal cases and their outcomes as indicators of the place women who labored in private houses and businesses had in nineteenth-century Brazil’s legal culture of work, we might say that the invisibility of female labor was its most apparent feature. These women engaged in extraordinarily difficult legal battles to demonstrate that they had performed genuine work; these battles mirrored their disputes over the definition of the real place they occupied in the homes where they lived. Their ultimately fruitless struggles to defend their personal respectability effectively rendered invisible both their productive labor and their role in the economic success of the men for whom they worked. And just as the value generated by domestic labor was obscured behind a haze of the legal ambiguity, as we shall see, women and their labor came to occupy a marginal place in the urban public sphere.

Figure 3 This cartoon, drawn by Angelo Agostini (1843–1910), is originally from Revista Illustrada, a magazine printed by the famous illustrator and publisher in Rio de Janeiro between 1876 and 1898. The image’s original context is a series of ironic cartoons about the reaction of Rio’s small business owners to the introduction of a “Consumer’s Cooperative” in the city. It depicts an everyday scene from inside a small dry goods store: on the left, the shop owner, very likely Portuguese, ponders the profits that he could have made by using tempered weights in his shop scales. On the right, a young caixeiro weights some flour or sugar while a woman drinks a glass of spirit (cachaça). Another patron watches the scene and laughs. She is wearing a piece of fabric tied around her head in a fashion that was common among quitandeiras, women of African descent (both free and enslaved) who used to work selling prepared food and vegetables in the city’s streets. Both pictures repeat common stereotypes about the habits and mores of Portuguese shop-owners and black women. Revista Illustrada, Anno I, n. 20, Rio de Janeiro, May 27, 1876. p. 8.

CONCLUSION: DIVERGENT TRAJECTORIES OF CAIXEIROS AND CRIADAS

The cases explored in this article present eloquent evidence of the trajectories – both interwoven and diverging – of caixeiros and criadas in the course of the nineteenth century in Rio de Janeiro. Although it would be impossible to discuss all the dimensions of these cases, we can reflect on some possible ways to understand this process as connected to the dynamics of labor relations in Rio, on the one hand, and to national politics on the other.

First, it is important to note that labor relations were inseparable from the social and demographic reorganization of the city, above all in the second half of the century. In the 1850s, with the freeing of capital after the end of the Atlantic slave trade, business owners began to invest in hiring European immigrants.Footnote 39 These were, in general, poor workers, both individuals and families, who made the journey to Brazil to do farm labor there in the hope of buying a piece of land and improving their lives. Whereas in other regions of the country immigrants moved to rural areas, including the recently created “colonies” that were organized to bring groups of foreign immigrants to establish agrarian settlements, recently arrived unmarried Portuguese often settled in the capital city, finding work in petty commerce or other forms of urban labor. Together with enslaved day laborers and freedpersons of African descent, these immigrants formed the basis of a heterogeneous proletariat and a large reserve of available, cheap labor.

In the two subsequent decades, the social and ethnic composition of Rio de Janeiro changed significantly. According to the census carried out in 1872, among the city’s population of 274,972 persons, 49,939 were still enslaved. The number of immigrant inhabitants of the city was 73,311, among them 55,938 Portuguese, of whom over eighty per cent were men. Whereas in 1849 out of every ten inhabitants of Rio only four were considered as white, in 1872, reflecting above all the large influx of Portuguese immigrants and the sale of many urban slaves into rural labor in the provinces, this proportion was inverted: for every ten inhabitants of the city, six were white.Footnote 40

This demographic shift is intertwined with other transformations in the organization of urban labor. The growing presence of Portuguese immigrants had a direct impact not only on the composition of the male working class, but also on the female labor market. As the historiography on urban commerce in Rio de Janeiro in the first half of the nineteenth century shows, the participation of African and Afro-descended women in retail commerce and in street vending was quite significant. Once the Atlantic slave trade definitively ended in 1850, however, this presence diminished markedly, and workers in commerce came to be recruited, albeit not exclusively, from the ranks of the city’s young, white men, primarily Portuguese and Luso-Brazilian men, often hired by their own compatriots.Footnote 41

The world of domestic labor offers a contrasting image. In 1872, 55,011 of the city’s workers were occupied in domestic service, of whom 41.52 per cent were enslaved and 58.47 per cent were free. This occupational category, the single largest listed in the census, accounted for seventy-two per cent of the 48,558 female workers in the city of Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 42 The end of slavery reinforced the feminization of domestic labor, because the labor market for men emerging from captivity gave them more opportunities to escape from the often oppressive circumstances inherent in domestic work, some of which this article has examined. With this, emancipated men turned out to be better positioned than women under the same conditions to strive for and to attain, however limitedly, those ideals of both freedom and masculine respectability that entailed the expectation of removing one’s self from the bonds of personal dependency that were inevitable in domestic labor.Footnote 43

The gradual exclusion of women, particularly those of African descent, from commercial occupations in Rio de Janeiro reinforced the place of domestic labor as a primordial space of work for poor women during this moment of massive immigration around the time of abolition. Freed women, who had found more opportunities for gaining access to urban occupations during earlier periods, appear to have seen these opportunities diminishing, not only due to competition in the commercial realm as it became an increasingly masculine and “whitened” space, but also because of the emergence of models of female respectability that cast negative judgment on their public sociability and marginalized their independent labor arrangements.

The difficulty of making a clear distinction between women’s work as criadas in the private, domestic territory of homes, on the one hand, and as caixeiras in small businesses on the other, recalls another characteristically indistinct feature of women’s working lives in nineteenth-century Brazil: the ambiguities female laborers confronted as women sought their place in the public sphere of collective politics, the space where people constructed a “working-class” identity. Through studying the legal cases presented here, we can draw connections between this private sphere of residential homes and commercial establishments on the one hand and the public sphere mediated by an institutionalized justice system on the other. The cases examined here and others like them allow us to think about how, as they traversed these two spheres, people constructed and transformed the relationships between caixeiros and criados and the law, between these types of workers and political and judicial institutions, and between these and other types of workers. Thus, through these cases, we can investigate the process through which certain categories of workers managed to distinguish themselves from the rest, mobilizing the meaning of respectability and citizenship and fighting for political and social rights.

The Brazilian Constitution passed in 1824, two years after independence had established the right to vote as a constituent element of male citizenship. All male “Brazilian citizens in enjoying their political rights” and “naturalized foreigners” could vote and run for public office, as long as they met the minimum income requirements. Even male former slaves could vote in local elections, as long as they were Brazilian-born and fulfilled the rather restrictive income requirements. The Constitution excluded from the electorate not only non-citizens (foreigners and slaves), but also women, minors, and criados de servir (a disenfranchised category of criados that explicitly excluded the more respected primeiros-caixeiros and guarda-livros or bookkeepers).Footnote 44 Yet, in contrast with criados and male freedpersons, and even male foreigners who could acquire at least some of the attributes of male citizenship, being a woman was an insuperable barrier to active citizenship for maids, women shop workers, and elite women alike. Thus, it is not surprising that this gender distinction played a fundamental role when caixeiros and criadas tried to find or to transform the place they occupied in the political world as well as public recognition of their work.

From the 1870s on, caixeiros’ struggles for regulation of the operating hours of commercial establishments, as well as the articulation of these struggles with both the republican and the workers’ movements to abolish slavery, turned on these workers’ efforts to distinguish themselves from the indistinct universe of servile labor that brought them closer to criados and domestic maids.Footnote 45 The personal and collective affirmation of the dignity of work and of the “clerking” class – a classe caixeiral – expressed itself in the language of male citizenship and public rights, distancing themselves from the subaltern (and emasculating) character of personal servitude and domesticity. These gendered and class dynamics fueled the divergent trajectories of caixeiros and criadas and made this divergence into an entrenched reality.

Meanwhile, in the final decade of slavery and the years immediately after abolition in 1888, municipal authorities became especially interested in regulating and controlling domestic work. The government proposed legislation that attempted to establish a caderneta, a logbook in which to register labor contracts and the professional histories of domestic criadas and criados, under the control of the police. Once these regulations were finally approved in the early 1890s, their enforcement met with resistance from the very group for which the law had been passed, and it was never implemented.Footnote 46 Municipal power thus functioned in strikingly different ways for these two types of workers. For caixeiros, the proposals for regulation came out of their political intervention and from the pressure they exerted on legislators and other public authorities. In contrast, the various proposals presented in the Municipal Chamber, the local governing body, in the course of the 1880s to regulate criados of both sexes, resulted from legislators’ concerns about the need to control this mass of workers who, soon to be removed from any of the ties that bound them to slavery, continued to occupy domestic spaces and, dangerously, to share the intimacy of their bosses. In their various versions, however, legislative bills that aimed to regulate domestic service managed to displease both employers and workers. The employers because they objected to the interference of public authorities in private business (who to hire to work in one’s own home, and how) and they opposed the limitations on their freedom to hire. The workers because they saw it as an attempt to control them and limit their freedom in general, subjecting them to the strict vigilance of the police authorities and uncomfortably reminding them of the final years of slavery.

José do Patrocínio and Machado de Assis, two of the era’s most important commentators and both Afro-Brazilian, had telling reactions to the laws governing these prevalent forms of urban labor. The important abolitionist politician José do Patrocínio (1853–1905), writing about a proposal to regulate the service of criados, affirmed that it was a “new law of dissimulated slavery”, and for that reason was rejected by “public opinion”.Footnote 47 For his part, in the same year and just months after the abolition of slavery, the renowned writer Machado de Assis (1839–1908) argued that “all liberties are siblings” in voicing his support for a movement by caixeiros to pass legislation that regulated the working hours in commerce.Footnote 48

Thus, as we have sought to demonstrate in this article, female domestic workers’ aspirations for citizenship and for public recognition of their work ran aground in the emerging definition of male citizenship, which stood in explicit contrast to domesticity. Public space and politics actively excluded women, whose difficulty in having their labor valued and their rights recognized in the public and legal spheres both antedated and resulted from this exclusion.

At the end of the nineteenth century, caixeiros made up a respectable part of the urban working class of Rio de Janeiro, organized in associations and capable of having their demands for improved working conditions recognized by municipal authorities and in legislation. In contrast, during the same period, the professional reality of female domestic workers looked very different: placed at the margin of the organized working class, confined to labor arrangements marked by domesticity and paternalism, the law only saw them as objects of political and sanitary regulation, with little or no recognition of any direct link to their condition as workers.

Translation: Amy Chazkel