The institution of slavery permeated all aspects of social, cultural, and economic life in the early modern Atlantic world and has left a lasting legacy. The adverse effects of the slave trade and slavery in the Atlantic world and their association with anti-black racism have inspired the United Nations to declare 2015–2024 an International Decade for People of African Descent.Footnote 1 The history of slavery in the Atlantic world is determined by the trafficking of twelve million Africans to the Americas and their forced labour in plantation agriculture, as well as their resistance to this exploitation. Trade, agricultural labour, and resistance are central to understanding the transatlantic slave system that developed between Europe, Africa and the Americas. Given this context, the prevalence of an “agricultural myopia” in slavery studies comes as no surprise and few would argue that the emphasis on plantation slavery has been misguided.Footnote 2 However, the importance of cities to the functioning of the Atlantic world, as nodal points in networks of trade, centres of power, places where enslaved people were held and employed and where racial hierarchies were forged, should not be overlooked.Footnote 3

To date, the attention to slavery in the cities has often been limited to observations about the greater agency of city slaves.Footnote 4 This emphasis on urban slave agency in scholarship has a long history. The former slave and astute critic of American slavery Frederick Douglass had observed a key difference in the degree of freedom that urban slaves enjoyed compared to their counterparts on the plantations. Douglass wrote in his memoir that in the city “a slave is almost free”. He also suggested a reason for this by arguing that “slavery dislikes a dense population”.Footnote 5 In this same vein, Ira Berlin has emphasized slave independence in the urban context. His masterful Many Thousands Gone has inspired scholars for over a generation, even if the limits of his analysis of urban slavery are becoming apparent. In the book, urban slaves primarily appear to illustrate the contrast with their rural counterparts by showing themselves to be artisans and tradesmen and displaying independence, even when they survive as prostitutes.Footnote 6 More recent studies of the freedom that urban slaves occasionally enjoyed have begun to recognize more readily that urban life also involved public displays of racial hierarchy on city streets. Surely, bondsmen in cities had access to more opportunities and institutions that could protect them from their master's whims than their rural counterparts; but urban slaves were far from immune to the violence and cruelty that characterizes slavery around the world.

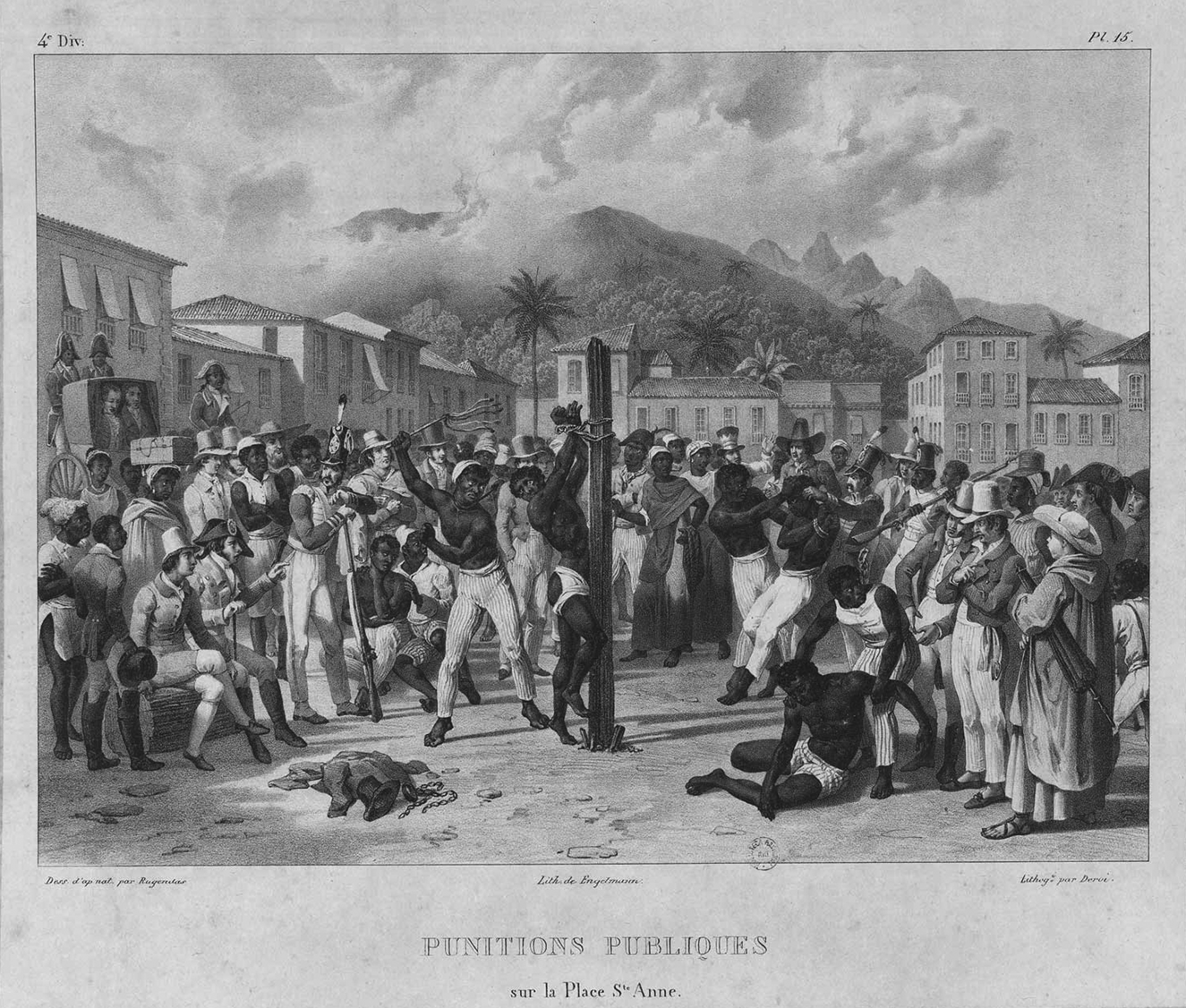

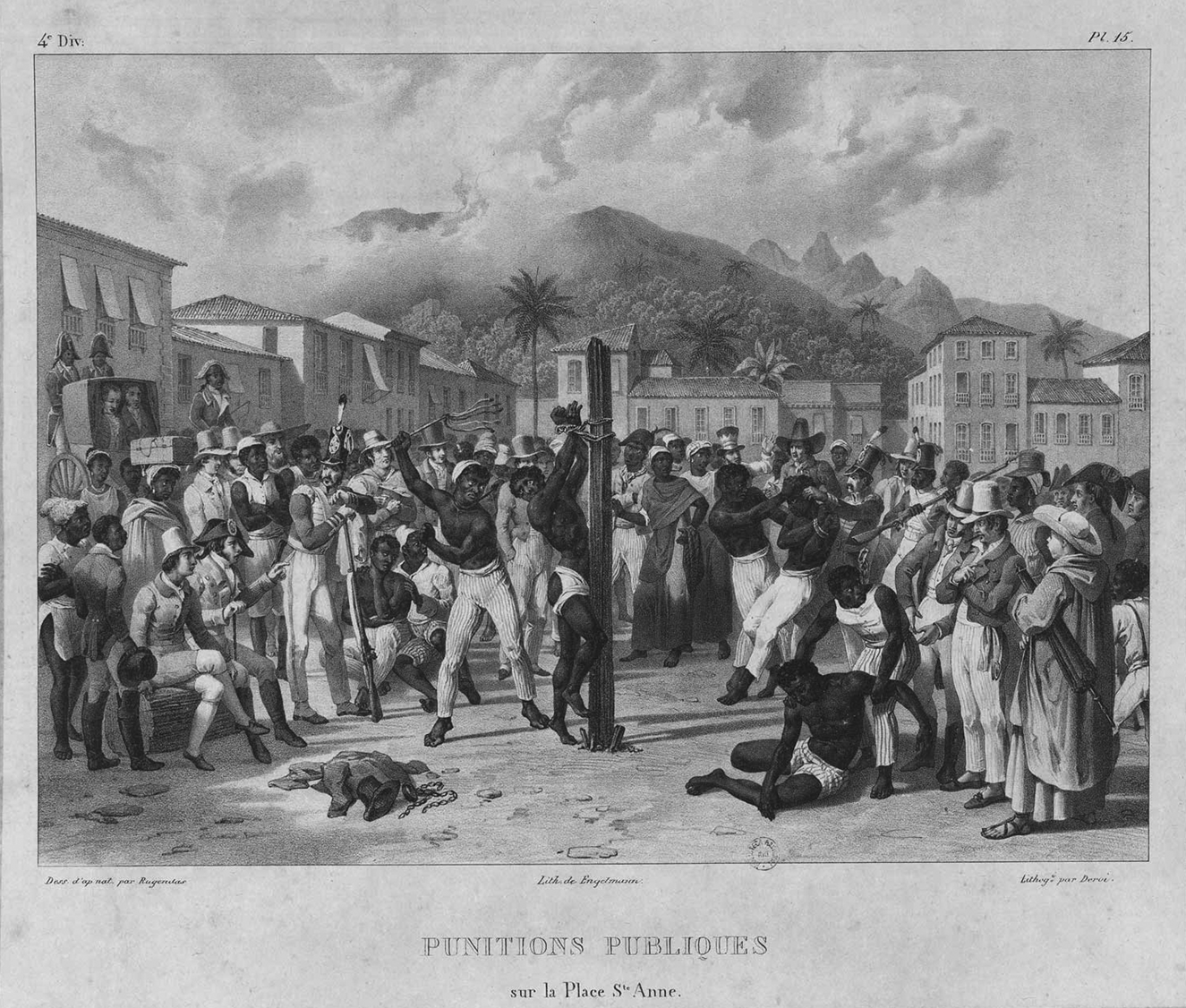

In her study of Bridgetown, the capital of Barbados, Marisa Fuentes reminds us of the violence of slavery in port towns. In the city, the strictures of slavery made “resistance to domestic violence a life and death decision”.Footnote 7 The enslaved women of Bridgetown were “battered, beaten, executed and overtly sexualized”.Footnote 8 Cities were sites of a “veritable terror” and served as stages where the slaveholding elite displayed its dominance through ritualized acts of disregard for enslaved life.Footnote 9 From Iberia, the Atlantic cities inherited the practice of segregating the execution of freedmen and slaves, emphasizing the difference between them. In many Atlantic cities the pelourinho (pillory) was a visible reminder of the consequences of transgressing the limits set by enslavement (Figure 1). Affirming the hierarchy did not only have a function in urban life but was part of the relation between town and country. If conflicts between overseers and slaves escalated on plantations, the masters could restore the subjugation of the enslaved by moving them to the city for punishment. This urban function could only be performed as long as cities were – at least in their daytime appearance – spaces of unchallenged white slaveholder power. The traditional emphasis by historians on slave agency in cities might have overlooked how important the affirmations of hierarchies in cities were for the survival of the system itself. The proposition of this Special Issue is to regard the interplay between urban and agricultural areas as communicating reservoirs of labourers and sources for slaveholder power and authority as well as their contestation. The more nuanced understanding of the possibilities and limits to slave agency in the city that has been developing in recent years, and an appreciation of the role of cities in the slave system as a whole, raises new questions about the period in which slavery was beginning to be abolished around the Atlantic world.

Figure 1. Public whipping of an enslaved man in present-day Campo de Santana in Rio de Janeiro.

SECOND SLAVERY AND THE ATLANTIC CITIES

From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, cities in the Atlantic world were primarily formed as a function of the trade and shipping between European markets, American plantations, and West African slave forts.Footnote 10 The economic function of these port cities shaped their occupational structure, and their near-universal reliance on slave labour. The mainstay of the occupational structure of Atlantic port towns was (as in any pre-modern society) composed of activities that were directly needed for the social reproduction of the town, rather than for industry or trade. As Wim Klooster demonstrates in the first contribution to this issue, slavery was integrated into every part of the occupational structure of these towns and slaves were a substantial part of the urban working population. These towns existed in relation to the trade lines, mines, and plantations in the hinterlands. Given the agricultural nature of the societies, the urbanization ratio was surprisingly high in the Atlantic colonies. It hovered around ten to twenty per cent in the Caribbean, which is a percentage that most of the rest of the world did not reach before the twentieth century.Footnote 11 The proportion of slaves to non-slaves in cities was always lower than it was in the plantation areas. Nevertheless, the proportion of slaves in the city could rise to over sixty per cent of the population in such emblematic plantation colonies as Saint-Domingue, Suriname, and Jamaica.Footnote 12

By the late eighteenth century, the cities of the slave societies of the Atlantic world displayed common traits and comparable occupational structures. Much of the labour in the cities was done by enslaved women, without whom a city like Charlestown “would have ceased to function as a commercial centre for the cotton trade”.Footnote 13 The different empires diverged somewhat when it came to building up administrative functions in their oversees towns, with the British being rather frugal, while the Spanish and French had a more sizeable body of officials in their ports.Footnote 14 Landowners were largely absent from the Atlantic ports in the early period, with the exception of the larger ones, such as Charleston, Havana, Salvador, Recife, and Rio de Janeiro. Lack of land (and slave) owning elites in towns had been a sign of the frontier nature of most of these ports. This changed in the eighteenth century when capital started to accumulate in the colonies themselves and, on top of mercantile and administrative functions, the port cities of the Atlantic world became places where landowning elites congregated. This concentration of economic elites in the city was slightly offset by absentee ownership, with plantation owners residing in the French, Dutch, and British metropoles. Although absenteeism has garnered quite some attention from historians, the impact of this was minimal at most, and was even less important in the United States, Brazil, and the Spanish domains.Footnote 15 By the eighteenth century, urban slaves were engaged both in the maritime and mercantile activities of the town and in the households of the urban elites. Domestic and household work was quickly seconded by activities directly servicing trade and shipping. Being indispensable to the functioning of the cities made the abolition of their enslavement unimaginable to slaveholders.

By the late eighteenth century, slave owners clinging on to their slaves in town and country kindled fierce debates about the abolition of slavery in many societies in the Atlantic world. However, with the abolition of slavery in many of the formerly Spanish colonies, the temporary abolition in the French domains, and the end of the slave trade in the British empire, the beginning of the end of the institution arrived in the Atlantic world. Despite the beginnings of abolition, the importance of slavery to the Atlantic economies was far from diminishing. Transatlantic slave trading expanded after British abolition, as did slave-based plantation production. In the South Atlantic and on Cuba, the slave system was granted a new lease of life in the nineteenth century, and in the United States South, slavery entered a second phase of expansion and intensification that lasted until the Civil War.Footnote 16 Also in African societies, the nineteenth century “was more firmly rooted in slavery than ever before”.Footnote 17 In Kingston, Jamaica, the ending of the slave trade seems to have had only a limited effect on the city. Trevor Burnard finds that the number of urban slaves increased after the trade was abolished.Footnote 18 The end of the slave trade shifted economic activities away from the plantations and towards servicing trade in the region – which was more of an urban activity. On the other side of the Atlantic, as Mariana Candido shows, the ending of the slave trade led to an increase in the number of urban slaves. In Benguela, the port through which the highest number of slaves passed into the Atlantic system, the end of slavery increased urban slaveholding as well as slavery in general.Footnote 19

The nineteenth-century resurgence of slavery, sometimes characterized as the “second slavery”, is strongly associated with the migration of slaves within slave societies. In plantation-rich Brazil, on Cuba, and in the United States South, train tracks were adopted early to facilitate the movement of people or goods between the port cities and the plantation areas.Footnote 20 Viola Müller notes that second slavery meant that a lot of enslaved labourers were moved from the city to the countryside – a move that has been noticed in many cities during this era.Footnote 21 In Brazil, the internal slave trade shifted the presence of slaves to the areas of the coffee boom, and the percentage of slaves in the urban population declined to fifteen per cent on the eve of abolition.Footnote 22 The forced migration to the newly expanding plantation areas coincided with a redirection in the routes of the transatlantic slave trade. The trade itself expanded despite British abolition and numbers of enslaved Africans in the Atlantic rose in this period. In the cities, the wars and revolutions had also increased the numbers of free non-whites in many colonies.

ABOLITION AND THE CITY

The new literature on urban slave and freedmen communities increasingly recognizes the role of familial ties, kinship, and the entrepreneurial role of women.Footnote 23 As Mariana Dantas and Douglas Libby argue in this issue, free black families naturalized the idea of black freedom and therefore played an important role in conceptualizing what life after slavery should look like. In the past, historians primarily recognized that urban societies, for all their complexity, had been places where there were clear limits to the power of slave owners over their slaves, even if this did not make slavery incompatible with urban life.Footnote 24 Atlantic cities provided an example of a future beyond slavery, and an example that politicians and administrators could view with optimism. Abolitionists on Puerto Rico tried to placate those who were apprehensive about abolition by arguing that urban slaves “have always seen public authority over the master's authority, respecting both”.Footnote 25 As one of the leading powers in the Atlantic world, British abolition imbued others to take that same decision. Movements for abolition were very much an urban affair, both in Europe as well as in the Americas. In Rio de Janeiro and many other Brazilian cities, the abolitionist movement changed politics and public engagement. And the presence of these movements in the cities put pressure on the practice of slavery in these places.Footnote 26 The violent removal of abolitionists from slaveholding towns like Charleston were not uncommon in this era.Footnote 27 In Atlantic cities, former slaves were able to rise through the ranks and build meaningful lives for themselves, making the success of these urban communities an argument in the discussion about the feasibility of a complete abolition of slavery.

Attention to gender is changing the appreciation of the transformative processes that took place in the age of abolition. The status of the former slave is different from those who were freeborn, and both in the city and on the plantation the consequences of this distinction were gendered. The form in which the British legislators imagined to bridge slavery and post-slavery was through a typically urban institution of apprenticeship. Apprenticeship had a nice emancipatory ring to it, while leaving in place a role for the master. By imagining post-slavery as apprenticeship, the suggestion was made that the former slaver would be trained to become the master of a trade and through that the self-supporting director of his own future. The reality was very different. In its Atlantic agricultural context, apprenticeship meant nothing but a continuation of the same unskilled sugar cane cutting labour that the field slaves had performed before abolition. For women, apprenticeship proved a double-edged sword; not only did it mean a continuation of agricultural labour, in many cases their role in the workforce was reduced. While women made up a large share of field workers before abolition, they were denied a role as wage earners after it. Notwithstanding the continued marginalization that also plagued them in the city, their ability to manage property and contribute to developing independent communities was greater there.Footnote 28

Urban communities of former slaves were important in shaping post-slavery societies. The managing of slaves and former slaves in cities took one of two routes. In the cities themselves, there was a pattern in which distinctions were made between slave and former slave based on legal status. In other cases, we find the opposite. Legal status was deemed irrelevant and racial categories were strengthened, legally pushing black people, irrespective of their status, into the same neighbourhoods and excluding them from citizen rights. Abolition was accompanied everywhere by the promotion of respectability, Christianity, education, the nuclear family, and loyal citizenship. Slave women's respectability and public roles were pushed to the margins, while male labour became more transient and mobile. In the French Caribbean islands, a trek towards the urban estates followed the abolition of 1848. In the city, slaves were looking for legal redress and the protection of urban institutions.Footnote 29 In the Dutch Caribbean, the movement of slaves was restricted at the moment of abolition. The date of the actual abolition was chosen to fall in the middle of the rainy season, to further prevent movement between plantations and to the city and further restrictions were put in place to keep people from settling in town.Footnote 30 Still, if second slavery had been a move to the countryside, the abolition of slavery led to a move towards the cities where former slaves joined the communities of free people of colour that had developed from the eighteenth century onwards. These cities tried to deal with these free migrants by segregating them and developing a prison system that specifically targeted the former slaves. The United States abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime” and after abolition the prison system flourished in former slave states, as it did in Jamaica and in other post-slavery societies.Footnote 31

In some places, the rise of the community of free people of colour threatened the position of the urban slaves in the nineteenth century, in others no distinctions were made between the two categories, but were perceived as a single threat to urban society. As a response to that perceived threat, Brazilian urban governments began to restrict the economic activities of freedmen and slaves in the city, even raising taxes for freedmen who continued to reside in the city of Salvador.Footnote 32 As Marion Pluskota shows in this issue, the mobility of slaves and former slaves was a prime concern around the Atlantic. When slavery returned to the French Caribbean, the authorities on the islands began to police the movements of slaves and created policies to keep them out of the cities. The growth of the slave population and their increased mobility created new fears of insurrection, and these fears were exacerbated by the traditions of newly arrived slaves to congregate in cities for annual festivals. In cities like Santo Amaro, in Bahia state, the slaves would meet in large numbers. Once they arrived from their separate plantations, they dispersed according to their African nation for religious celebrations that bordered on revolt.Footnote 33 In Rio de Janeiro, severe control was enacted to limit rebellions during these tumultuous periods. Enslaved craftsmen were often found at the head of the urban rebellions of slaves in Brazil.Footnote 34 Vagrancy laws were also introduced in the British Caribbean, and in Brazil, in 1832, both freed and enslaved Africans were to carry a passport at all times.Footnote 35

Second slavery's pull to the agricultural production areas did not mean that slave labour in the city was no longer profitable. In Puerto Rico, the demand for domestic slaves was high and the relocation of slaves to the countryside threatened the status quo.Footnote 36 In the United States South, the value of educated and skilled urban slaves rose in the last decades before the Civil War.Footnote 37 As the Richmond Inquirer noted, “[a]s carpenters, as blacksmiths, as shoe-makers, as factory hands, they [slaves] are far more valuable than field laborers—indeed, intellectual expertness and manual dexterity are much more important elements in the price of a slave than physical strength and power of endurance”.Footnote 38 Looking beyond the immediate dynamics of labour demand and supply, Richard Wade has noticed that the problem was control once the slaves were off the job. Life in the city, if they mingled with the other slaves and the rest of the population, made them “insolent” and therefore “worthless” to the owner.Footnote 39 Despite these pressures on urban slavery, even during the expansion of the cotton plantations in the US South, urban slavery in a city like Macon, located in the heart of the cotton boom, saw a continuation as a “viable economic and social institution”.Footnote 40 Even if, as in the case of Macon, the percentage of slaves declined from 55.1 per cent in 1830 to 34.4 per cent in 1860, the real number of urban slaves increased from 1,452 to 2,829 in this period.Footnote 41 In the areas where slavery continued there was an uneasy balance with other supplies of labour. These areas appear to have been unattractive to free European migrants who had no wish to compete with slaves in the United States South. Industrialization did take place on a limited scale, but European free labourers did not move to the towns of the south.Footnote 42 If urban slavery declined in those years, as Hardesty shows for Boston in this issue, it was not because the labour demands in the city were diminishing. Instead, he shows that when the post-slavery future appeared on Boston's doorstep, racism, among other factors, pushed free non-white labourers from the city.Footnote 43 With the abolition of slavery on the agenda, the racial logic underpinning Atlantic slavery was entering a new era in which it would no longer be supported by slave laws but would still be constitutive of social hierarchies.

AFTERLIVES

What scholars have rarely done to date is to consider the long-term legacies of urban slavery and its memorialization in cities around the Atlantic. Abolition singled out slavery as a form of labour mobilization that was no longer permitted and was primarily focused on the plantations and the slave trade.Footnote 44 The campaigns to abolish slavery firmly imprinted in the public's mind the image of the slave ship and the plantation as the sites of ultimate terror. The horrors of agricultural slavery and the slave trade became the main argument as to why the institution should be abolished. The policies that accompanied abolition aimed both at providing economic continuity and social stability. The issue of social stability meant that many slave societies at the time of abolition grappled with a transformation of their practices of citizenship and race. Although, most notably in the African context, abolition made it clear that slavery did not need a formal institutional framework to persist. The abolishing states in the Americas were all primarily concerned with how the newly freed population would have a place in the labour process. There was a great fear that abolition would leave former slaves without any motivation to work on plantation estates. This meant that the former slaves would have to learn to exercise self-discipline rather than being disciplined by an external force or, as Sir James Stephen in the Colonial Office once famously summarized, they had to replace the “dread of being flogged” with the “dread of starving”.Footnote 45

There was a great optimism about the post-slavery future at the moments that abolition occurred around the world, and, even if governments were concerned about economic and social stability, the new equality before the law was embraced. The French were asked to “forget all distinctions of origins”, and on the British islands it was declared that the law should no longer favour Europeans or be to the “prejudice of persons of African birth or origin”.Footnote 46 This was not only a view espoused by government officials. In liberated Charleston, the white German population initially held festivities that included and welcomed the active participation of freed Afro-Americans.Footnote 47 Despite the initial optimism that surrounded the abolition of slavery, the legacy of slavery returned to haunt post-slavery societies. The upsets of the racial and status hierarchies between slaves and non-slaves would come to be reaffirmed. Former slaves continued to carry a stigma of slavery that classed them lower than those who were freeborn, and post-emancipation racialization protected part of the old social hierarchy between slave and free around the Atlantic.

Restoring the older hierarchy depended on practices of distinction between town and country on the French islands and in Brazil, urban segregation in the United States, as well as, almost everywhere, direct assaults on the civil rights of former slaves. Urban freedmen asserting their newly acquired civil rights were met with great violence during the New Orleans Massacre of 1866 and similar events in Memphis and Charleston that year.Footnote 48 This type of violence against former slaves and their offspring continued for decades. Although largely a rural phenomenon, the most iconic of the close to 5,000 lynchings in the post-slavery United States South were staged in towns. The terror was far from over once slavery was abolished. The violence was both physical and cultural. The end of slavery led to an increasingly malicious culture of ridicule and degradation of the former slaves in towns. The black-face minstrel shows were not only mocking rural slaves, but with the character of Zip Coon, sometimes called Urban Coon, racists explicitly targeted the educated, cultivated, and upwardly mobile freedmen in cities that were regarded as “uppity”.

Cities remained sites of the important struggles around (de)segregation, civil rights, and equality waged around the Atlantic world from the late nineteenth century onwards. Even where rights were won, people of African descent and of slave descent continue to be marginalized. Part of this is reflected in the stark difference between the way the history of slavery is purposefully memorialized in urban spaces.Footnote 49 Social marginalization is accompanied by a silencing of the history of slavery. Former slave societies are often very slow to incorporate their past into urban public spaces, and when they do, the history of urban slavery is replaced with that of the slave trade and plantation slavery. Kingston in Jamaica typically makes reference to the abolition of slavery, but the role of the city in the slave trade and its dependence on slave labour is nowhere reflected in the urban landscape. In metropolitan cities, the history of slavery is beginning to surface, taking traces of urban slavery in its wake.Footnote 50 As Samuel North shows in this issue in the case of Cape Town, the urban history of slavery has become a contested element in politics and the formation of political identities.Footnote 51 Contemporary cities in the United States and Brazil rarely mention the relics of slavery and few of them have monuments commemorating the enslavement that took place in the cities.Footnote 52 Places that were built using enslaved labour also do not mention this fact or refer to the revolts that shook the cities. This began to change in important ways during the Obama presidency (the president himself was referred to as uppity – the derogatory reference to the urban freedmen) with the installation of statues of black leaders and acknowledgement of slave labour that was used to build such structures as the Capitol and the White House, and ongoing research into the slaves who worked on the Smithsonian buildings.Footnote 53 In New York, the discovery of the “African Burial Ground” just beyond the old city wall forcefully pushed the history of urban slavery into the city's public space. In Philadelphia, no visitor can reach the Liberty Bell without first passing through the ruins of the house of George Washington in which the lives of his house slaves are detailed in writing and on video screens. In Brazil, this is still another matter, although some exceptions exist. In Porto Alegre, a sculpture and explanatory sign mark the location of the place where slaves used to be hanged.Footnote 54

Yet, victimization seems the sole gaze through which the history of slavery can be regarded in many of these cities.Footnote 55 The image that sites of commemoration project is often informed by abolitionist propaganda, and ignores, among other things, the urban context of slavery, which was one of skilled craftsmen and often predominantly women. In cities, specifically, Araujo has found a form of “memory replacement” in which the general history of the transatlantic slave trade and plantation slavery trade fill the gap in places where specific urban experiences could be placed. Studies of urban slavery and the place of slavery in the history of cities has the potential to connect present-day offspring of slaves and slave owners to their shared slavery history. Thematically, attention to the urban context infuses the memory of slavery with examples of urban revolt and the role of women in slave societies, as well as their agency in shaping life in urban slave and freedmen communities.Footnote 56

CONCLUSION

The study of urban slavery has often only emphasized the greater prosperity and agency of urban slaves. Shifting the focus to the age of abolition, when the institution of slavery was in turmoil, allows for a more nuanced view of urban slavery and its afterlives. In the articles in this Special Issue, the emphasis is on the changes that took place in the cities of the Atlantic world once the abolition of slavery came on the agenda. The beginning of the age of abolition was marked by the intense mobility that accompanied the wars and revolutions of the end of the eighteenth century. The rise of the cotton industry, the belated Brazilian coffee boom, and the expansion of slave-based sugar production on Cuba gave a new lease of life to an institution that many had thought was dying. The reconstitution of political order and the reaffirmation of slavery and race relations in much of the Atlantic world of the nineteenth century greatly impacted slavery in cities. When full abolition came to the societies around the Atlantic, the cities became poles of attraction for former slaves seeking the institutional, economic, and cultural advantages of joining urban communities of freedmen. The state and former slave owners as well as lower-class whites grew increasingly suspicious of communities of former slaves, and combinations of segregation, imprisonment, and violence followed. The history of urban slavery is rarely part of memory cultures around the Atlantic world. The legacy of the abolitionist campaigns that focused on slave ships and plantations still dominates our understanding of slavery in the present. For descendants of slaves, the rediscovery of the history and legacy of urban slavery presents a way to connect their identities to the centre of many of our contemporary cities and offer a story of belonging.