“A guild”, in the words of one historian, “is not necessarily a guild”.Footnote 1 I read this to mean that the fit between the formal shape of a guild and the significant functions that a professional organization is expected to perform is not always close. Organizations called “guilds” may not serve all or any of these functions, and organizations having other names may serve some of them. It is necessary, therefore, to begin by locating where this paper stands in the varied meanings of the term.

In the extensive scholarship on the European guild, both the political-administrative agency and the economic agency of medieval guilds have received much attention. Guilds functioned as a link between the government and the urban population, as “instruments of the municipalities”, or “agents of council policy”.Footnote 2 Indeed in some contexts the supervision of the town population, including taxation, was considered by some historians as “the most important function” of the guilds.Footnote 3 The guild and polity relationship has been shown to vary greatly; these variations are explained differently as a strategy either to contain the guild or to empower it.Footnote 4 These moves were influenced by the state’s search for efficient fiscal agents, by the guild’s own successes or failures in adapting to industrial capitalism, by political and juridical aspirations, and on a more ideological level by the tension between corporatism and individualism.Footnote 5

On the economic plane, the guild joined “the ‘mystery’ of craftsmanship […] with the dynamics of pressure groups”.Footnote 6 More narrowly, the guild was a means to regulate competition and deal with some forms of market failure and incomplete markets.Footnote 7 Price and quality regulation is a common example of product–market regulation. Entry fees and other types of control in artisan guilds intervened in the labour market in two ways: delivery of training, when the market did not supply technical education, and regulation of competition, especially competition between masters and apprentices. The guild could reduce risks of the trade cycle. It could be a source of credit when capital markets did not exist for its members. In the market for entrepreneurial resources, guilds curbed free riding by means of privileged access to information and entry fees that can be seen as royalties charged on intellectual property. In these senses, the guild system was the collective answer to several types of hazards of premodern capitalism: quality concerns, free riding, and the absence of intellectual property rights. In the scholarship on merchant guilds and similar coalitions, it has been suggested that one of the functions of the guild was to protect property rights by creating incentives for honest behaviour.Footnote 8 Formally, the objective was served by means of an elaborate system of rules governing membership, conduct, and reward; these rules became laws thanks to state sponsorship.

The guild might also give rise to governance costs. The tension between masters and journeymen was forever present. Craft and merchant guilds could come into conflict. Political power and privileges could encourage corruption. Training rules could be bent to advantage sons over apprentices. Monopoly rights could be abused to restrict trade. These costs created incentives for individuals to leave or bypass the guild, or form another one, depending on the conditions of membership. The guild, in principle, could contribute to (or stall) economic growth depending on how efficiently it served the positive functions of the expanding market economy and on how efficiently it avoided governance costs at the same time.

In early modern and modern India, guilds fulfilling the minimum formal characteristic – a written charter establishing a right to conduct business and accepted by the members as well as the local or supralocal authority – were rare, if not unknown, even in the context of urban crafts or commerce. Institutions did exist that contained some features of the medieval European guild, but these institutions appear in the major sources as obscure and marginal, and the distinction between the professional side and the social-cultural character of these collectives appears blurred. In particular, I have found no significant example or reference to a body of producers with written statutes and an explicit role in urban administration.Footnote 9 In some way connected with this informality, the political agency of the guild was also weak, random and obscure in south Asian sources. The politico-administrative role of the guild will, therefore, be absent in this paper altogether.

And yet, any well-developed commercial-industrial system needed collective solutions to the transaction costs discussed above, and south Asia was no exception to this. Collectives were formed to address these challenges. The precise manner in which associations appeared to deal with these problems varied even within India. The major concern of this paper will be with the economic functions of the guild, including a descriptive account of these diverse mechanisms. Its attention shifts, therefore, from the guild as a corporate body with political effect to informal collectives formed in response to some of the economic problems to which the guild was a response. This shift of focus raises two important problems for historiography; first, the problem of origin, and second, the problem of effect.

Where did these informal associations spring from? Did they originate in social institutions, such as kinship, community, or caste? Or, were other associational models present in the pre-modern south Asian economy which could be adapted to meet more specific capitalistic needs? The social origins of producer or merchant associations cannot be discounted completely, and yet there are large examples that do not fit the social origins model well. More specifically, of the two general prototype quasi-guilds I discuss later in this paper – the master artisan and the community – the latter fits the social origins model, whereas the former does not. I return to this theme in the concluding section, which argues in favour of the second view.

The historical link between guilds and “development” depended not only on the direct contribution of the guild in making markets work better, but also on externalities: fostering innovation, collective spending on charity and welfare, the effect of the guild on law-making, and cultivation of an idiom of solidarity, in which Black traces the roots of cooperative socialism in the nineteenth century and Robert Putnam locates the roots of political reform in modern Italy.Footnote 10 We cannot address this major project here. Clearly, the larger sense of craft communities that I shall be mostly dealing with was indistinct from a European guild in some of these respects, say, in promoting reciprocity and structuring hierarchies. I think the main difference between south Asia and Europe rested on the relationship between the guild and the state. There are in south Asia instances of the state granting monopoly rights to collective bodies. But these bodies were caste collectives rather than guilds. And such instances remain rare in late medieval to modern India. An important implication of an active agency of the state was the indirect effect of guild statutes, contracts, agreements, and covenants upon the formation of common law. Law was also an instrument to defend the guild, as evidenced in the series of “combination laws” in early eighteenth-century England.Footnote 11 The formal institutionalized guild was potentially an agent in the creation of a public good, whereas community-bound bodies and rules created private, rather “club” goods in the sense of a language of law that only a few understood. Even where associations served the same general goals that guilds served anywhere, the spillover effect of guilds was possibly weak in south Asia.

In the next section, the late medieval organization of production and trade is discussed. In the section that follows, several nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century associational models are described. The last section provides a conclusion.

Artisan and merchant collectives in late medieval India

Scholarship on industry in the seventeenth century suggests the presence of a fundamental separation between the agrarian subsistence economy and the towns where the political elite and, in the south Indian context, the great temples were located. The rural world of manufacturing rarely supplied goods to the rich urban consumers.Footnote 12 There was little social and intellectual intercourse between the rural and the urban artisanate. At least in south India, this separation was maintained by social legislation that prohibited the rural artisans from encroaching on the preserves of the urban artisans.Footnote 13

Most illustrations of formal or informal collectives in this paper originated in the towns. The urban artisan was highly skilled and highly organized, but the organization was shaped by the clientele they served. Whereas the rural artisan typically worked with family labour, the urban artisans worked within collective bodies such as communities or master–apprentice teams where the respective positions of the masters and the apprentices were clearly defined. It would appear that the master artisan was much more than a skilled individual; the master was also the channel of negotiation and contract, if contract is the right word, between the elite consumers and the artisan communities. The master was a “craftsman-contractor”, to borrow an expression from Ramaswamy.Footnote 14 The exclusive privileges of the community and that of the master within it were maintained by the state or the temple.

Much of our knowledge about the medieval urban crafts derives from accounts of European travellers such as François Bernier or Francisco Pelsaert, or that of the court functionary, Abul Fazl. Abul Fazl does mention the existence of “guilds of artificers”, and guild-masters, in whose appointment the town administrator had a say. That being said, the picture of work organization that we receive from these accounts suggests that these guilds worked as adjuncts to another powerful institution, the karkhana. Karkhana literally means factories. In this context, the term did not necessarily mean factories, but included factories along with stores and some administrative departments. The main north Indian seats of power developed a hierarchy of karkhanas owned by courtiers and individuals close to the court, though much more is known about the imperial karkhanas.Footnote 15

Two features of this institution are noteworthy. First, by means of karkhanas urban north India became culturally at home with the idea of collective work, which is the context in which master–apprenticeship relations crystallized into a system of unwritten rules. Second, while the karkhanas did not necessarily rule out private production for the bazaar, they did represent a subversion of the market. The extent of subversion varied. It was, however, important enough to be mentioned in all major studies on the karkhanas. The subversion happened in three ways. There was implicit or explicit control of the courts on purchase of inputs. The output was rarely marketed but kept for royal use, gifts, even provincial revenue payments, and exports. And the karkhanas tended to recruit the best workers in the industries. They had the authority to make sure that the best workers did not refuse an invitation. The distinction between the rank and file and the elite among the artisans was mediated by proximity to power.

The presence of a hierarchy is suggested also in the account of European travellers. The most famous description is that of Bernier, who distinguished between two types of urban artisan. At one extreme was the bazaar artisan who was nominally independent, that is, not an employee of the rich and powerful, and yet a perpetually poor man, lowly skilled, and subject to all kinds of arbitrary bullying and exploitation by merchants or agents of the rich. At the other end was the elite among the artisans, the super-skilled artist, who was necessarily an employee of the karkhana. Thus, “[t]he artists […] who arrive at […] eminence in their art are those only who are in the service of the King or of some powerful Omrah, and who work exclusively for their patron”.Footnote 16 As for the rank and file, “virtually every relevant feature of the economy, society and the state was designed to hold the artisan firmly down to his lowly place […]”.Footnote 17

Thus, this world of urban crafts was shaped, above all, by the consumer demand of a few hundred families that commanded almost the entire agrarian surplus of a large region. Powerful, extremely rich, and few in number, these buyers of craft goods employed artisans directly. There was no “market” worth the name. They were the market. The skilled artisanate, even whole industries, functioned mainly in a relationship of dependence on public authority. They were not employers. The courts did not depend on them. They were not a source of tax revenue for the courts as their European counterparts were. They were employees or quasi-employees of the court.Footnote 18

Clearly, guilds were not needed for market regulation in this context. The master’s power reflected that of the patron. Since there was no effective market, the guild did not have any commercial interest to serve or protect. For the same reason, nor was there much entrepreneurial resource to protect. And yet, precisely because the crafts in demand were particularly intensive in craftsmanship, training was a vitally important issue. So was regulation of competition in the labour market. The guilds, such as there were in urban north India, were either bodies that maintained the hierarchy of craftsmen, or quasi-administrative bodies engaged in facilitating transactions conducted by the courtiers.

In the somewhat better-known scholarship dealing with the medieval Indian merchant, the irrelevance of the merchant guild has been argued by some historians along quite similar lines. In the history of the European and to some extent of the Middle Eastern guilds too, we observe a relationship of mutual dependence between the merchants and the state. In India too, there was mutual dependence between the merchants and the states, a dependence which in fact played a pivotal role in political transition in the eighteenth century. And yet, this dependence had quite a different flavour from what we observe in the history of the European guild. The eighteenth-century dependence was driven by short-term self-interest rather more than by recognition of long-term compatibility of interests; it was influenced by the fiscal collapse of the post-Mughal successor states, and it represented collaboration between political elements such as the individual princes and the merchants rather than between the state as the law-making institution and the merchants. Were guilds unattainable in south Asia? Were guilds unnecessary in south Asia?

Were guilds unattainable? Were rulers simply disinterested in the subject of granting exclusive rights to merchants? We must begin from the quite extensive scholarship on the merchant–state relationship in Mughal India. Perhaps the orthodoxy here is represented by a view that suggests a broadly hierarchical and at times repressive relationship between the state and the merchants. Sixteenth-century travellers in north India articulated this idea. It had a long life among historians, and in broad terms was accepted by scholars of the Aligarh School. In the modern version of the same thesis, the Mughal state did not need the merchants as an ally because it earned more than enough money from land taxes.Footnote 19

In Mughal India, taxing the merchant was not a significant source of income for the state, and was thus left to a certain degree of arbitrariness, allowing local agency, and even extortionist practices. The bureaucratic state might stifle guilds or pre-empt them in two ways, by making merchants an unimportant actor in fiscal administration, and by an atrophy of the town government, which became a mere point of land-tax administration rather than that of mercantile enterprise. This model can be contrasted with economic change in late medieval Europe wherein the state’s dependence on land taxes had fallen, the town had emerged a source of tax, merchants and urban administration could both be better off by collaborating, and the guild acquired its distinctive rights, even though these rights were later sold and resold to others, and eventually revoked.

It needs to be noted at this point that in subsequent research on south Asia, the concept of the bureaucratic state has been questioned. Princes who owned merchant marines, or the “portfolio capitalists” of the south-eastern coast, and the notion of a “segmentary” rather than centralized state, modify the state–merchant opposition in fundamental ways.Footnote 20 Reinterpretation of eighteenth-century northern India as a world in which merchant capital consolidated itself has a similar implication.Footnote 21 If the centralized state concept needs revision, it remains true that a great deal of the commercial opportunities in the south Asian world was tied to land and land tax. In that sense, merchant capital, where it was successful, was either relatively marginal to the territorial states, as in the case of the Indian Ocean trade, or part of their fiscal enterprise, as in the case of revenue farming.

If the formal guild or monopoly rights were unattainable, for most purposes it was rendered unnecessary in the presence of other types of collective institutions. Let us return to the artisan first. We know little about how the north Indian karkhana survived the eighteenth century. The history of some industries, such as shawls in Kashmir, suggests that the karkhana became a private firm catering to merchants in overland trade with Europe.Footnote 22 In those industries where long-distance trade developed early, karkhanas must have altered their nature earlier. But such early transition was almost certainly not the rule. By and large the concentrations of skilled artisans in the eighteenth century tended to be in cities with powerful regimes. The fundamentally non-market character of most karkhanas might have diminished, but it did not wither until the nineteenth century. I shall return to the theme of what happened to the karkhanas shortly.

The material on regions outside the Mughal heartland is somewhat obscure by contrast, except that for the Vijayanagara Empire in the early sixteenth century. Historians have noted the general scarcity of trade guilds in the Deccan, with the significant and noticeable exception of Ahmedabad. It is possible that trade guilds existed in the eastern Deccan, the later Maratha territories, before the Muslim conquest, and atrophied thereafter. When in 1675 the British in Bombay tried to revive the goldsmiths’ and silversmiths’ guild in a bid to prevent debasement of metals, the attempt had to follow British statutes and conventions rather than any existing Indian custom.Footnote 23 Important historical studies on merchants and artisans in medieval south India do mention the term “guild”, but they supply rather little information on the internal structure of these collectives, and so their similarity or otherwise with respect to European guilds remains open to interpretation.Footnote 24 Nandita Sahai, who has studied artisan groups in eighteenth-century Jodhpur, seems justified in cautioning against the use of the word “guild” in the context of Indian artisan collectives, a point raised also by M.N. Pearson in his review of Meera Abraham’s work.Footnote 25

Possibly in varying degrees in all regions, the power of the patrons with almost limitless purchasing power had dissipated by the mid-nineteenth century, so that whatever collective institutions there were before had to become market-oriented. We now come across a number of descriptions of collectives – in some cases the word “guild” is actually used.

The four clusters into which I find it convenient to classify the nineteenth- and twentieth-century examples of collectives of producers or traders are: the Ahmedabad guilds, artisan panchayats, master–artisan collectives, and merchant communities. Between them, the nature of the regulatory system differed. The Ahmedabad guilds came closest to being formal associations, but restricted themselves to regulation in the product market. The second group, master artisans, was mainly interested in devising collective rules to regulate the labour market. The third and the fourth groups both involved the play of informal associational rules such as castes and communities to serve regulatory ends. These two sets of cases, therefore, will be prefaced with a brief description of the relevant meanings of caste and community in this context. The third group, artisan panchayats, was engaged mainly in regulation in the product market, occasionally devising rules for work and workers as well. In the most famous of these four examples, merchants used “community” to regulate distribution of entrepreneurial resources such as capital and trust.

Castes, guilds, and masters in colonial India

Ahmedabad trade guild

The strength of the institution in this one town is evident from its survival into the nineteenth century. W.W. Hunter’s Imperial Gazetteer observes that:

[…] the system of caste or trade unions is more fully developed in Ahmadabad than in any other part of Guzerat. Each of the different castes of traders, manufacturers and artisans, forms its own trade guild. All heads of households belong to the guild. Every member has a right to vote, and decisions are passed by a majority of votes. In cases where one industry has many distinct branches, there are several guilds.Footnote 26

For example, among potters, the gazetteer reports the existence of separate guilds among makers of bricks and tiles, and makers of earthen jars. In “the great weaving trade”, silk weavers and cotton weavers belonged to different guilds. The objects of the trade guild were, “to regulate competition among the members, and to uphold the interest of the body in any dispute arising with the other craftsmen”.

One interesting instance of collective bargaining is cited. In 1872, the cloth merchants decided to reduce the charges customarily paid to the sizers. The sizers went on strike. Both actions were possible because of the existence of associations. The dispute lasted six weeks, before an agreement was signed on stamped paper. One common instance of regulation of competition was the agreement to work short time. In 1873, the Ahmedabad bricklayers experienced a sudden increase in competition from among daily wagers. Given the allegation of rising unemployment, the guild met, and decided that none should be allowed to work extra time. “The guild appoints certain days as trade holidays, when any member who works is punished with a fine. This arrangement is found in almost all guilds.”

The decisions of the guild were enforced by fines. But often there were cases of members refusing to pay. Then – the members of the guild all belonged to one caste – the offender was expelled from the caste. If the guild included men of different castes, the guild used its influence with other guilds to prevent the recusant member from getting work. These fines and a steep entry fee from anyone wishing to start a trade in the town formed the income of the guild. The entry fee was perhaps correlated with the skill required: “[N]o fee is paid by potters, carpenters and other inferior artisans.” Further, for a son succeeding a father in the licence to carry on an independent business, the entry fee was waived. “In other cases the amount varies, in proportion to the importance of the trade, from £5 to £50.” The guild spent its money mainly on community feasts and, on rarer occasions, general charity. The guilds also maintained community hotels.

Master artisans

Around 1900, royal karkhanas affiliated to regional courts still existed, but they were not the principal employers of skilled artisans of the towns. Most artisans worked for the market in very different systems. Interestingly, the terms that described urban artisan organization in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – karkhana, karkhanadar, ustad, and shagird – were inherited from the pre-colonial period. The term karkhanadar deserves particular attention because it symbolized regulation and hierarchy of an informal kind.

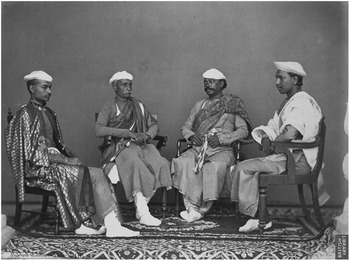

By 1900, the word karkhana had bifurcated into two distinct sets of meaning. Outside northern India, in the handloom weaving towns of Bombay-Deccan, karkhana referred to any small factory and the karkhanadar to the generic owner of the factory. In the case of the early nineteenth-century Kashmir shawl, the term karkhanadar referred to owners of karkhanas, who in turn hired masters (we see a collective of such master artisans in a late nineteenth-century photograph in Figure 1). In this wider usage, the words had clearly lost the institutional distinctiveness and political character that they once represented in the urban artisanal tradition of the Gangetic plains.Footnote 27 In its homeland in north India, however, karkhana retained shades of the older meaning. Here again, karkhana referred to a workshop, but the karkhanadar was not necessarily the generic owner, but a master. In the late Mughal system, the word karkhanadar referred to an administrator, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to a skilled master with some access to community resources for labour control.

Figure 1 Designers in a carpet factory, Kashmir, c. 1890. Photographer unknown. © British Library Board. All rights reserved.

Most instances of collectives that we do come across in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries refer to the regulation of master–apprenticeship relations and the protection of knowledge.

I consider first three sets of studies of the karkhanadars of Benares (silk), Lucknow (embroidery), and Moradabad (brass). In these three examples of established urban crafts that survived into modern times, the karkhanadar played multiple roles. There was first of all a simple management function: avoiding fraud. In Lucknow, “orders in bulk are not generally trusted to the ordinary workman until he can show some standing as a karkhanadar”.Footnote 28 There was, secondly, a more complex management function: coordination. In United Provinces generally, the karkhanadar often coordinated between processes. But he also kept accounts, guaranteed quality, and supervised and trained artisans.Footnote 29 Supervision and training were widely believed to be the most important roles, and in some situations dominated the other roles of coordination and trust. In Benares brasswares, “the karkhanadar’s position is that of a foreman in a factory […]. The karkhanadar has little connexion with the business side of the industry. The karkhanadar is only responsible for the work by the workmen. Usually he permits a few apprentices to be taken in by the workers”.Footnote 30

Karkhanadars, thus, were men “higher in status than the workmen. Every workman, therefore, aspires to become a karkhanadar […] several workers sometimes combine to run karkhanas on a profit-sharing basis (e.g., brass workers of Benares)”.Footnote 31 Since the karkhanadar was not strictly a capitalist, the worker working under him was “neither strictly a wage-earner […] nor precisely a home-worker. He is a combination of the two and perhaps more of the former”.Footnote 32

The propensity to form a cohesive group entered this ambiguous relationship between the karkhanadar and the worker, especially where some training was involved. Karkhanadars tried to regulate the progression of workers into their own ranks. According to reports, anyone with some money and a reasonable reputation could set himself up as a karkhanadar. But a moral economy intervened. Karkhanadars insisted on rules governing time of service. In Lucknow embroidery,

It seems to be an unwritten law with the karkhanadar that until a man can show some six years’ work in the city he is not to be given the full wage. And the worker, whatever efficiency he may have obtained, submits to the rule, for the refusal to accept underpayment may mean starvation for him.Footnote 33

In Benares brassware and cotton-carpet manufacture, “apprenticeship is restricted within the caste”.Footnote 34 In Moradabad brassware, there was a rule that if any karkhanadar trained one from outside the community, he would be “outcasted”.Footnote 35

There are references in these sources to how artisan collectives became vulnerable. In Moradabad, a brassware training school was established, so that “the barrier, even when it exists, is slowly and steadily declining”.Footnote 36 When demand declined or quality became a less serious consideration than before, merchants often dealt directly with artisans rather than with karkhanadars. And, in one interesting example, in Lucknow, the embroidery craft slowly passed from men to women inside households. “The spare-time workers […] are satisfied with almost any remuneration”. Women rarely combined, questioned the authority of the dealers, or negotiated with them, and therefore the merchants/artisans dealing with women did not need the protection of a quasi-guild.Footnote 37 Extending the same principle, in the 1920s the craft moved further away from city women to rural women “in the villages around Lucknow who are content with even lower wages than their sisters in the city”.Footnote 38 In new and relatively more mechanized trades, such as the manufacture of knitted textiles, the karkhanadar felt much less threatened by the worker. Individual craftsmanship was a less important resource here than was capital. The masters themselves opened training classes which anyone could join.Footnote 39

The master–apprentice relation was governed by a set of rules that had enough force in the interwar period to ensure that new entrants followed them. The clearest expression I can find of these rules comes from the cities of northern India, mainly Lahore, Amritsar, and Agra. The artisans were mainly Muslims, who recruited apprentices from outside their immediate families. By contrast, Hindu artisans in southern India by and large worked in family units. Recruitment occurred along hereditary lines rather than within a formal master-student system.Footnote 40

A 1940 description of artisans in Lahore offers a detailed picture of the former system.Footnote 41 The report surveyed conditions mainly among carpenters, blacksmiths, metalworkers, and bricklayers. Like many other commercial-industrial cities of the time, Lahore had experienced a construction boom in the 1920s fuelled by profits made during World War I. The four types of artisan surveyed were directly or indirectly connected with the building trade. At the time of the survey, the industry was recovering from the worst effects of the Depression, when all construction activity had stopped. This unusual situation colours the description to some extent.

Some of the main features of employment practices need to be stated. There was a deliberate attempt to keep family and apprenticeship distinct; even when the father was an artisan, it was customary to have the son trained by another master (ustad), or face the stigma of being called a be-ustada or self-trained. On completion of the training, the ustad issued a sanad, or licence. Some artisans were “of the opinion that all the earnings of an artisan would be haram (unlawful) unless he got a sanad”. But this statement hints at the existence of such unlawful practices in some quarters.

The apprentice paid only a token fee to the ustad at the time of joining, which consisted of a turban, a scarf, and sweets. He was expected to render services not only in the workshop, but also at the master’s home. This description referred to a period when the demand for apprentices was brisk, and the apprentices themselves on occasion received some money. The period of apprenticeship varied between one and ten years. If the apprentice came from an artisan family and had already been trained well, the training period could be very short. For someone without previous exposure to the craft, the training period could be long. In the construction trade, long apprenticeship was common because many new entrants came from a farming background.

While entry from peasanthood to artisan occupations was relatively easy in some cases, exit from artisan occupation could be difficult. “According to some Muslin tarkhans [carpenters] their family traditions were such that they could not give up carpentry and take to a new trade; to do so made one an object of ridicule in the biradari [literally brotherhood or fraternity] and even deprivation of its privileges, such as inter-marriage.”

Attainment of masterhood had meaning not only inside the trade, but also in the wider market for high-quality skills. For example, when they hired a construction supervisor or a contractor railway workshops looked for persons with the ustad status. Being a “licensed” artisan was not necessarily the same as having a reputation in the trade. Fresh graduates of the apprenticeship system followed individual masters in the early days of their careers, until they themselves were well enough known to receive independent contracts.

The term “guild” does appear in this description in one context. Raj was the name given to the ustad in the building trade “by the ancient ‘guild’ of brick-layers”. No details are available on this institution. If it ever existed, its disappearance was easily explained by the entry into the building trade of the rural classes, an effect of the 1914–1929 economic boom in Punjab. A more informal collective was the biradari. Its significance appears to have been confined to imposing some form of social sanction for breaking an undefined set of rules.

From elsewhere in the urban crafts of interwar India, glimpses of a similar set of practices can be had. One example was the cotton-carpet industry of Patna City, where “The work generally is done by hired labourers (under the guidance of one who may be called master worker or Malik of the Karkhana) who are all Muslims”.Footnote 42 There is a mention of biradari among artisans of urban North India in one source on silk weavers.Footnote 43 But, as Yusuf Ali, the author of this work himself noted, nowhere did biradari mean formal rules and regulations. “Organized guilds” in that sense “are unknown”.

In historical documents of the kind considered above, the reference to caste and community tends to be persistent. How do we conceptualize the relationship between castes and guilds?

Caste, community, and guild

In The Religion of India, Max Weber claimed that “[t]he ‘spirit’ of this caste system […] was totally different from that of the merchant and craft guilds”.Footnote 44 How valid is this claim? The usefulness of caste or jati as a category of economic history is a deeply controversial issue. References to caste in sources on the artisan or the merchant suggest two dimensions of caste, both potentially relevant for the present discussion. First, occupational specialization was influenced by birth. And second, caste sometimes involved a sense of community that could be used to build formal or informal cooperation.

Weber followed the former route, and considered the caste system to be an intercommunity division of labour cemented by religious ethos. In this view, the core attribute of caste was “vocational stability”, made possible by the belief that one’s occupation was preordained, and outside one’s personal choice. Weber thought this attribute of Hinduism explained a particular Hindu work ethic, “characterized by the dread of the magical evil of innovation”.Footnote 45 In an important section titled “caste and guild”, Weber proposed two fundamental dissimilarities between caste and guild. First, the guild did not imply denial of the freedom to choose occupation. And second, the guild allowed for a degree of “fraternization” among artisan groups, whereas “the magical distance between castes in their mutual relationship” maintained a fundamental barrier between occupational groups in Hindu India.

This line of conceptualization has been deeply problematic. Attempts to discover a persistent core of orthodoxy in the Hindu religion, a definite connection between social organization and religious texts, and a rigid historical link between caste and occupation, the tenets on which Weber built his thesis on the Hindu work ethic, have long been questioned by sociologists. On all three points, the society of south Asia shows too many variations over time and between peoples to be reduced to a set of principles.Footnote 46 Based largely on readings of texts, Weber took the essential features of the caste system to be immutable, and moved back and forth between ancient and modern India as if caste formed a stable bridge across time. The recent historiography of caste claims that the essential features were in fact created, or at least fundamentally restructured, by colonialism or late medieval economic and social upheavals.Footnote 47 Finally, the religious route Weber took left him poorly equipped to deal with the Muslim situation, a weakness he covered up with tentative assertions about differences between the Hindu and Muslim work ethic, exemplified by the statement that “the Hindu artisan is […] more industrious than the Indian artisan of the Islamic faith”.Footnote 48

The more flexible and tractable definition of caste for the economic and social historian is that of a group sharing affinity, or an endogamous group. This group does not have to share an occupation, or subscribe to a Hindu ideology about occupational choices, in order to survive as a caste. And yet, for many early modern artisans and merchants, the group did share an occupation. In such cases, significant interaction between its economic interests and social practices could develop. For example, marriage alliances formed among families that shared a similar economic profile, and barriers to marriage were used to separate the urban artisan elite from their rural brethren, even when they shared the same caste name. One would also expect some degree of intra-group compulsion upon members to follow their traditional occupation, for the sense of a shared calling was also a basis for desired marriage alliances.

Caste in this sense was a possible foundation for a link between kinship and control over business resources. But caste was neither a necessary nor a sufficient foundation. Any endogamous group with a shared calling was potentially capable of creating such a link. In this sense, the term “community” is preferable to caste, for such groups existed among merchants and artisans across religious boundaries. Kinship fostered a system of exclusive control of useful knowledge, including trade secrets, and social incentives such as the promise of a good marriage enforced behaviour codes. There were attempts in modern south Asia to fashion formal associations out of castes and communities. However, the caste association was never purely, not even primarily, an economic institution. From early modern times, as far as one can see, the caste associations settled mainly disputes of a social nature. In an era when merchants and artisans were more mobile than before, these associations were the means with which collective social identities would be preserved.

Castes and communities could foster collective regulation of resources, secure trust, and organize training and apprenticeship. These were the same functions that the guild served too. Therefore, this sense of caste or community does not place caste and guild in mutual contradiction, as Weber did. But does that mean caste and guild were identical institutions? I will argue later that it does not, and that informal and formal collectives differ in a number of respects.

The relevance of community to the study of modern Indian mercantile and industrial enterprise has been stressed by many scholars, even if, as Helen Lamb observed, community was probably just a transitional phenomenon.Footnote 49 “Community” has tended to be used in two general senses, a group sharing kinship, and a networking group. It is clear that in several contexts from south Asia these two senses necessarily overlapped. Nearly all illustrations of business community suggest that marriage and kinship cemented these groups. Community, thus, was a collection of families connected both socially and through business ties. Caste in this context defined the boundaries within which marriage could occur. And yet, these groups were neither just a collection of families nor just a club, and by no means did community imply equality within the group. Rather, business communities were hierarchical organizations. The patterns of hierarchy were fashioned out of kinship relations in a selective way. In the so-called family trees of business families, for example, one would observe specific rules of succession and male preference along with respect for seniority (we see three generations of bankers in a mid-nineteenth-century group photograph in Figure 2. Note the combination of European and Indian furnishing in the room). The end of the community, an ongoing process in south Asia, has usually involved challenge to these rules by insiders.

Figure 2 Bankers in northern India, 1863. Photographer: Shepherd and Robertson. © British Library Board. All rights reserved.

Further, this collection of families was also rather like firms that were shaped as much by family values as by business values.Footnote 50 Brimmer writes that “there existed between the family-firm and the trading community of which it was a member an informal relationship symbolized by a very strong sense of responsibility for the well-being of one’s community fellows and an overt preferences for dealing with them”.Footnote 51 Keeping trust in the presence of asymmetric information was one important function of the business community.Footnote 52 A variety of other support functions, such as supply of credit, easier travel, profit sharing, and apprenticeship, were also usually involved. Community has also been used to suggest degrees of entrepreneurial exposure, closely related to training and apprenticeship, and in the sense of exclusion.Footnote 53 While the link between social ties and community ties remains open-ended, the creation of cooperative community usually goes along with a more general process of identity-formation, of which there are many examples.Footnote 54 In some ways, bankers furnish the best example of cooperative communities.

The two studies that follow illustrate the workings of community for the regulation of business resources among artisans and merchants.

Artisan panchayats

Although institutionalized forms of association such as the Ahmedabad guilds remained rare in colonial India, a variety of clubs and customs were mentioned. The most common local terms were panchayats, community associations, and biradari, the latter a term with a significant historical association with the guild. These clubs were almost always present in craft towns of the western Gangetic plains, especially when artisans-cum-merchants were handling expensive raw material.

A nineteenth-century example is the smelting of precious metals. To maintain purity, smelting used to be done in Lahore, Delhi, and Lucknow, in communal premises monitored by bodies such as town councils. The furnace was maintained in return for a fee imposed on all members of the silver or jari merchant community. In the 1880s, it was found that the fee had no legal force. “Renegades” took advantage of this, and eventually the payment ceased, weakening the very institution itself.Footnote 55 There are further examples of a similar nature from the interwar period from Benares:

A distinct set of goldsmiths called sodhas handle gold and silver bars for converting these to wire. They are prohibited from dealing directly with the gold and silver merchants until the bar passes through the panchayats of the sodhas who guarantee the weight in payment of a fee from both the merchants and the goldsmiths.Footnote 56

From the same town, among the silk kamkhwab weavers: “There is no union or trade guilds but customs are observed like laws, and so there is no lack of discipline. A few years ago, a disciplinary committee was formed and constitutions were made […]. But the committee failed due to the manager’s embezzlement of the common money.”Footnote 57 This example thus reveals the contradictory nature of the attempt to create a formal guild. The desire to do so was surely driven by a sense that custom could potentially fail to serve as law. On the other hand, the scope for free riding was greater in a formal guild, which could not access informal means to enforce discipline.

The brotherhood concept spilled over to the merchants too, who in Benares silk weaving rose from the ranks of the artisans themselves. “There is a compact sense of brotherhood among the different members of the panchayats.”Footnote 58 In this case, the commitment was used to protect advances made to individual workers. If anyone disappeared with the money, the panchayat made sure that the person did not take a job with another member.

Artisan panchayats could take up technological challenges. In perhaps the most well-known example, these efforts made the panchayat and the kinship community almost indistinct. The Sourashtras were a small group of silk and cotton weavers and dyers based in textile towns of south India, the most important settlement being Madurai. Numerous reports from the colonial period suggest how the economic growth of Madurai owed much “to the prosperous and industrious community of Saurashtra merchants and silk-weavers, who have […] come to a foremost place among the ranks of [the town’s] citizens”.Footnote 59 Madurai silk derived its historic reputation mainly from a red dye. In the late nineteenth century, when the dye material changed from a local plant to the mineral-based dye then imported, the adaptation of the dye to the particular style of weaving posed a problem. The problem was solved largely through collaboration between a German dye-maker and a few Sourashtra technicians-cum-entrepreneurs. Once the new technology was found usable, it spread quickly among the community. But it needed specialized factories to enable standardization and economies of scale in handling raw material. “Red factories”, consequently, mushroomed. Fifteen years after the first experiment, “the suburbs of Madura are now almost entirely covered with drying yards”. In 1921, half the Madras Presidency’s import of synthetic dyes went to just one town.Footnote 60

The period between 1880 and 1920 witnessed not only the economic transition described above, but also the deployment of an explicit sense of community to restrict access to the new knowledge and to diffuse class formation within the group. A number of contemporaries attributed the quick spread of the new knowledge and yet its restriction to one town and one group to the role of “caste” as a craft guild. What mattered was not only that the owners of the dyeing factories knew the specific formulae, but that they could secure cooperation from the workers not to work for or divulge these formulae to outsiders. Skill retention and training are described by observers in terms that almost depict a formal guild. Indeed, in some of these writings, the word “guild” was used.Footnote 61 And yet, no formal guild actually existed. What did exist was a correlation between community and skill, and attempts to perpetuate it. The following are two examples, fifty years apart. In 1925,

Closest secrecy is maintained in preserving [the Saurashtras’] trade secrets. Even in the employment of non-Saurashtra labour in the dyeing process, this point is as a rule strictly followed. Only Saurashtra workmen are engaged in the steaming process. In fact, wherever an element of brainwork is wanted, the Saurashtra maistries alone are wanted.Footnote 62

And as recently as 1976, “There are some trade secrets pertaining to the work of textile printing. These secrets are never divulged to any body, particularly a non-Saurashtrian. The non-Saurashtri labourers are engaged in textile printing, but they are not shown any secret of the trade.”Footnote 63

The other side of such exclusion was the “strong esprit de corps”, a constant theme in the context of Madurai’s quality of work. It can also be found or invoked in other contexts, such as the rarity of violent disputes, and diffused class formation. Even as capitalism grew roots in Madurai, Sourashtra production remained confined in families. Wage labour was conspicuous by its absence. To a large extent this was made possible by an informal agreement among the employers not to employ outsiders in this business. Indeed, new entry was so difficult that the textiles appeared as “virtually a closed industry so far as the labour force is concerned”, the stated reason being the historic association between Sourashtra labour and high-quality work.Footnote 64 The unity was also seen in matters of trust, “[T]hey are very keen to stick to truth in their dealings”.Footnote 65 And they “seldom borrow from other than their castemen”.Footnote 66 The beginning of the twentieth century also saw the most significant attempts to consciously recreate a Sourashtra identity. Linguistic-literary movements, and institutions associated with identity formation and the assertion of common identity, had their origin in these decades.

Merchant communities

Two groups of merchants and bankers from Shikarpur and Hyderabad in Sind, a province in Pakistan, dispersed across the world between the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries. The Shikarpur group financed overland trade between south Asia and central Asia, remitted money, and supplied credit locally. Their members set up posts in towns spread over a very large area, carrying on sometimes at risk to life and property. The Hyderabad group consisted of merchants who entered international trade later, but globalized operations in the same way, eventually setting up posts from Kobe to Panama. Both these cases of dispersal were associated with early modern trade, new consumption patterns in the west, new commodities in international trade, and rural commercialization in various parts of the world. Later, modern transport and communication played facilitating roles. The technological aspect of mobility, in fact, accounts for major differences between the two groups. That the merchants were subjects of the British Empire helped in most places except in Soviet Central Asia. But it did not impose an easily predictable pattern on the destinations.Footnote 67

Lower Burma became part of the British Empire in 1852. At that time the economic potential of the Irrawaddy delta was largely under-utilized, though the British understood this potential well. Among the many reforms enforced was a modified ryotwari, which enabled landholdings to be mortgaged. Between 1852 and 1900, cultivated acreage expanded by 5,000,000, and rice exports grew from less than 200,000 to more than 2,000,000 tons. The boom slowed in the early twentieth century as land became scarcer, and it ended in the Great Depression. Although in the early stages of the expansion, local labour and finance played a major role, after the 1880s labour and capital came from migrants. Between 1880 and 1930 the Chettiars, a merchant-financier community from Tamilnad, met an increasing part of credit demand among peasants, superseding Burmese firms engaged in credit and commerce. This ascendancy has been explained in terms of the Chettiars’ superior business organization, which had long been at work, and in particular to long apprenticeship, training in business ethics and techniques (such as a special accounting system), group solidarity, interfirm lending, and informal sanctions to minimize default within the group. Chettiar enterprise in Burma, however, became caught up in an economic and political crisis in the 1930s, eventually forcing most firms to leave Burma.Footnote 68

These firms formed “networks” in that the participants shared scarce resources such as credit and information. They functioned in environments that lacked efficient regulatory or communication systems. Yet opportunism and fraud by insiders did not threaten the network. The explanation seems to lie in the fact that the firms recruited principals and agents from the same social pool. Community was an important resource, and yet communal cooperation, founded on a mix of calculation and emotion, was neither invariant nor free from contradictions. A large part of the success as well as failures depended on who gave directions to whom. Hierarchical authority was intrinsic to the success of the community, but since hierarchies were often based on seniority rather than managerial competence, challenging authority was not unknown either.

In the nineteenth century, many Indian workers also went to work in the tropical colonies, and created settlements there. These settlements and the merchant diasporas differed on one significant point, among possibly many. With both labourers and capitalists, the individual who travelled abroad continued for some time to be part of the kinship-cum-economic unit that remained behind. In the case of merchant migration, the migrating merchant was no more than the agent of a principal back home, and these ties signified the existence of a family firm or a network of firms. With migrating labourers, these ties were more random, asymmetric, emotive, and possibly imagined, as a result.

Conclusion

I should like to tie up this diverse material by putting forward four propositions. First, the material suggests the rarity of associations containing the formal character of a European guild in late medieval to modern south Asia. It is not even certain that monopolistic and political professional associations ever existed, before disappearing through a competitive process. At least the existing evidence on the subject does not clearly point to such a hypothesis.

Second, collective regulation of product, labour, and entrepreneurship was common. The artisan panchayats, master–artisan combines, and merchant communities were all engaged in doing this. It is also possible, and indeed hinted at in the scholarship on the artisan, that the strength of caste and community associations increased from the mid-nineteenth century, signifying the fact that these institutions did have a positive role in mitigating the hazards of new kinds of competition.Footnote 69 In the case of North Indian karkhanadars I have suggested that these informal institutions may have had roots in older practices.Footnote 70

Can we read a pattern in this variety? Did regions, cities, and castes devise their own regulatory system in a random way, or was there a general framework of regulation underlying all these examples? This brings me to my third proposition, on the origins of informal collectives such as those we encounter in south Asia.

The third thesis of this paper is that the guild was unnecessary because two pre-existing models of control over entrepreneurial resources were already in existence: caste/community and master-cum-headman. The concept of caste surely merits serious consideration when we discuss any informal association in the south Asian context. I propose that the term community, in the sense of a collective related both by kinship and by a shared calling, is a more useful tool than caste. It does not exclude caste, and is more inclusive than caste.

This variable blend of kinship and knowledge that the community represented was not the only indigenous model of informal association. There were others. I have made the point elsewhere, in the context of labour control, that the early employers in mills, plantations, or overseas labour markets would have found two readily available models of labour organization in India in the 1830s, which I call the master-artisan model and the headman model.Footnote 71 In many villages under joint landlordship or with communal control over resources, the institution of headman was already firmly established. Contemporary observers noted the existence of a powerful headman in all such contexts. The most common mode of contracting in the nineteenth-century artisanate was putting out by using the services of a master artisan, or in some cases a headman in a weavers’ village. A great deal of the research on early modern textile exports from the Coromandel coast centres on the role of the headman. In both cases, one among the collective undertook to deliver a contracted quantity and quality of effort. I wish to extend this argument to the management of productive resources other than labour.

I also wish to suggest that these two were not necessarily distinct systems, but mutually compatible, and, on occasions, two sides of the same coin. In descriptions of the master artisans or the headman, the community was visible in the background. The head represented the channel of negotiation between the community and the market, a channel without which presumably the community would break up into chaos. In writings on the community, again headship was visible in the background. For communities based on kinship incorporated kinship notions such as seniority, rank, or great families in managing the conduct of their members. Community control over resources was prevalent and successful among south Asian merchants, as numerous studies have shown. In almost all cases, community and hierarchy joined together, and reinforced one another. In many instances from south Asia, what we observe is this community-cum-headman package, as an alternative to the guild. That being said, the master artisan was a particular kind of headman, in possession of technical knowledge and in principle a vehicle of innovation and a conduit for acceptance of innovation. I have argued elsewhere that this role of the master artisan as a skill leader introduced a certain degree of instability into the master-collective relationship.Footnote 72

If the third proposition dealt with the origin of informal collectives, the fourth deals with their effect. Even if formal and informal rules of association were at times equivalent in terms of regulation, these two models were not equivalent in terms of their spill-over effects. There were important similarities between community and guild, and important differences. The community was, like the guild or the firm, an institution that reduced certain types of transaction costs. Between these three types of non-market hierarchies – the firm, the guild, and the community – conditions of entry differed. The entry into a firm was conditional upon a promise to deliver services, that into a guild was fee-based, and entry in a community was relational. These relationships were structured by drawing on social relations and conventions. Thus, between the three, the community was by nature the most informal. And yet, that informality had notions of seniority, rank, and precedence built into it.

The exclusive control of useful knowledge by a group of practitioners and associational prospects between them made community akin to guild. In both cases, useful knowledge and trade secrets were club goods. Both clubs organized training and apprenticeships for younger members. And, by means of incentives and sanctions, both community and guild enabled maintenance of codes of conduct. That being said, the ticket to the caste club was birth, whereas the ticket to the guild was a market good. Both clubs tried to restrict access to useful knowledge, but in principle it was possible to buy one’s entry into a guild, and not into a caste club. None of these institutions was democratic. The community was probably the least democratic of all, since questioning economic authority in this set-up amounted to questioning social norms.Footnote 73

Formal and informal rules of association had different implications for law-making processes. Informal rules were not substantively equivalent, nor a sufficient substitute for formal statutes. The absence of formal statutes in India meant that when contract laws and associational laws were finally written out, the model was the English practice rather than any Indian benchmark.Footnote 74 Lastly, the community might at times create a conflict between two identities, professional and communal. Community-based alliances were social institutions that did contribute to a measure of mutual trust and responsibility in intracommunity dealings, but perhaps at the cost of the “consciousness of being men of the same calling”.Footnote 75 Caste brought people together, but only at the social level; and, I would add, it created divisions within a profession, for “birth still is a more important fact in India” than profession.Footnote 76 With a few exceptions, the associational principle has never had the chance to detach itself completely from hierarchical social relations in modern south Asia.