INTRODUCTION

This article aims to study the role of the Dutch colonial state with respect to changing household and gender labour relations in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It explicitly takes the colonial state, rather than the nation state, as its point of departure. Over the past two decades, postcolonial and post-nationalist studies have criticized the widespread idea of nations as self-contained units of analysis. Rather, they claim, colonialism ought to be considered as a consequence as well as a constituting element of European state and nation building since the seventeenth century.Footnote 1 From the late eighteenth century onwards, colonialism intensified, and the imperial project became a more explicit constituent of state formation. Moreover, this was the period when increasing colonial encounters highlighted the contrasts between the “advanced” colonial administrators and settlers on the one hand, and the “backward” indigenous population on the other. Such contemporary paradigms of modernity and backwardness, as well as notions of the “civilizing” mission of Europeans vis-à-vis non-European populations, have often been adopted by historians, who have taken developments in Western Europe and North America as blueprints for the “road to modernity” of other societies and cultures.Footnote 2 Instead, both postcolonial and “new imperial” historians have argued that, because of their interwoven histories, we need to study historical developments in “the East” as well as in “the West” in relation to each other, in order to better understand them.Footnote 3

In their inspirational work, Ann Stoler and Frederick Cooper have emphasized the many ambivalences of colonial rule, and pointed to the importance of recognizing how colonialism shaped the histories not only of the colonies, but also those of the metropoles. While the effects of such mutual influences on the metropole have often been indirect or even obscured, such “tensions of empire” are relevant for both the history of former colonies and former colonizers. Therefore, we need to “examine thoughtfully the complex ways in which Europe was made from its colonies”.Footnote 4 When we read or reread the historical archival material from this perspective – placing colonial history not solely in the context of domination and subordination – a more dynamic historical narrative emerges, characterized by tensions, anxieties and paradoxes, collaboration and resistance.Footnote 5 Examining these tensions and mutual influences will not only lead to a better understanding of the metropolitan as well as the colonial past, it can also help more fully explain the postcolonial remains of these complex relationships.Footnote 6

In order to investigate the influence of the state on gender and household labour relations in the Dutch empire, this paper compares as well as connects social interventions related to work and welfare in the Netherlands and the Netherlands IndiesFootnote 7 from the early nineteenth century up until World War II. This was the period in which the Dutch increasingly attempted to gain political control over the Indonesian archipelago, leading to an intensification of colonial contacts and significant social and economic consequences on both sides of the empire. I aim to show how state intervention, in this case by the Dutch nation state and colonial state, although differing in content and extent, was strikingly similar in terms of ideology and timing in both parts of the empire until the end of the nineteenth century. However, around the turn of the twentieth century, when in Europe – including the Netherlands – welfare states rapidly started to develop, social policies between metropole and colony diverged both in timing and effects. These differences were reinforced by changes in ideology, entailing strong gender as well as racial components, impacting drastically on diverging trajectories of labouring households in both parts of the world. While early nineteenth-century initiatives have been studied in the same analytical framework,Footnote 8 to my knowledge no similar exercise has yet been undertaken for the remainder of the colonial period.Footnote 9

This is highly relevant because important changes took place in the late nineteenth century, in which the welfare state slowly but surely emerged, at least in the metropolitan parts of the Dutch empire, whereas social legislation in the Netherlands Indies lagged seriously behind. Moreover, important ideological changes occurred in this period, which I believe contributed first to the simultaneity and later to the divergence of social policy in the different parts of the empire. In the beginning of the century, the political elites considered work by all members of the labouring classes – men, women, and children – to be the key to an industrious and blossoming society and economy, both in the Netherlands and in the Netherlands Indies. Towards the end of the century, however, the well-being of the poor and working classes became increasingly defined as a “Social Question” in the Netherlands, in which child labour and women’s work formed an important concern. Similar concerns led to the “Ethical Policy” in the Netherlands Indies in 1901, although attitudes towards the work of women and children here were far more ambivalent, as I will show. In the 1920s and 1930s, the ideal of the male breadwinner society had gained solid ground in the metropole, culminating in draft legislation to prohibit any paid work by married women in 1937, whereas work by women and children in the colony was conceived as rather unproblematic and even “natural” in the same period.

WORK AND SOCIAL DISCIPLINE: THE NETHERLANDS AND THE NETHERLANDS INDIES COMPARED (c.1800–1870)Footnote 10

Already in the early modern period, both in the Dutch Republic and the Netherlands Indies the rhetoric and policies of the authorities increasingly started to associate poverty with idleness. In the context of eighteenth-century economic decline, the answer to the growing problem of poverty was work: the idle poor should be transformed into hard-working and productive citizens. This rhetoric applied to lower-class men, women, and children alike. For example, Dutch welfare institutions increasingly restricted provisions for unemployed immigrants, begging was forbidden, and beneficial entitlements became increasingly dependent on people’s work efforts.Footnote 11 On Java, Dutch colonizers likewise condemned migration and “vagrancy” by the indigenous population as being economically counterproductive.Footnote 12 The number of local initiatives, such as workhouses and spinning contests to stimulate the production of fine yarns – typically the work of women and children – mushroomed in the Netherlands in the latter half of the eighteenth century. However, most of these initiatives failed. Often, the poor refused to work, or soon left the workhouse because of its bad reputation or because women and children could earn more and be more flexible elsewhere in the labour market.Footnote 13

Many early nineteenth-century policymakers as well as intellectuals believed that poor relief formed a disincentive for creating industrious, law-abiding citizens.Footnote 14 After the Dutch Kingdom was established in 1815, initiatives to combat poverty were taken at the national as well as the imperial level. Remarkably, King William I entrusted one particular person to implement his plans to counter pauperism by stimulating the industriousness of poor families, first in the Netherlands and later on Java. The man in question was Johannes van den Bosch (1780–1844), who had served as a military officer in the Netherlands Indies since 1799. He owned a plantation on Java, where he experimented with the cultivation of cash crops between 1808 and 1810. However, Governor General Daendels expelled Van den Bosch to the Netherlands in 1810, probably because of his criticism of colonial policy. Here, Van den Bosch successfully fought against the French in 1814–1815, a fact that did not go unnoticed by the later king.Footnote 15

Figure 1 Count Johannes van den Bosch (1780–1844). Governor General in the Netherlands Indies (1830–1833). Cornelis Kruseman. Donated by jkvr. J.C.C. van den Bosch, Den Haag. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. Public domain.

After the Vienna peace treaties of 1815, Van den Bosch spent most of his days designing plans to combat poverty in the Netherlands. He wrote an elaborate book on the problems of poverty, unemployment, and the desired role of the state. Although poverty was particularly dire in Dutch towns, Van den Bosch was convinced that – unlike in Britain – agriculture instead of industry would be the answer to the problem in the Netherlands. His earlier experiments with cash-crop cultivation on Java probably formed the foundation for Van den Bosch’s ideas.Footnote 16 He argued that the urban poor should gain the “right to work”, by having them relocated to rural regions where they could learn how to cultivate agricultural crops for their own subsistence, selling their surpluses in the market. With private funds Van den Bosch established the Maatschappij van Weldadigheid (Benevolent Society) in 1818 to set up agricultural colonies in Drenthe, an under-populated province in the east of the Netherlands consisting mostly of peatland. Tens of thousands of – mostly urban – pauper families migrated (and later were even deported) to these “peat colonies”. The idea was that several years in the countryside would turn them into industrious agrarian workers. Eventually, they were supposed to leave the colonies with some savings and an improved mentality.Footnote 17

Suitable colonists nevertheless proved hard to find, and “industriousness” soon needed to be enforced to a great extent. Some of the dwellings were transformed into penal institutions for convicted paupers. Even in the “free” peat colonies, regulations were strict and detailed. Throughout the 1820s, Van den Bosch regularly corresponded with the overseers, ensuring that they saw to it that “no household would be bereft of the necessary, but that it itself would earn these necessities”.Footnote 18 The meticulous detail of Van den Bosch’s calculations for the bare subsistence needs of households strikes the historian’s eye when reading the archival material. While undoubtedly benevolent in intent, the experiment with the peat colonies clearly shows that, to the elite, the poor were really a “foreign country”, as Frances Gouda has argued.Footnote 19 The initiative was an example of social engineering, and its overseers eschewed neither intensive control nor, at times, even force over the daily lives of ordinary people. A strict regime of meals, work, and rest was established, including only limited leisure time. Wages for field work were set at two-thirds of regular Dutch adult male wages, from which the costs of daily subsistence were subtracted.Footnote 20 Part of whatever a colonist family earned in excess of this had to be put into a health fund, part had to be saved, and part was paid out as pocket money. Their savings would enable the family to leave the institution within a couple of years.Footnote 21 In terms of the taxonomy of labour relations as defined by the Global Collaboratory,Footnote 22 this would thus entail a shift from labour relation 3 (unemployed) to labour relations 4a and 4b (leading producers and kin producers), 18 (wage earners working for non-market institutions), and 12a and b (possible surpluses sold in the market by heads of households and kin respectively).

In practice, though, the peat colonies increasingly came to resemble forced labour relations for a non-market institution (labour relation 8). Although Van den Bosch opposed slavery in principle, he could scarcely see the distinction between “forced” and “free” labour.Footnote 23 After all, every wage labourer was to some extent enslaved, as he (and less commonly she) was always economically dependent on a boss or employer, and therefore Van den Bosch was not against the coerced adoption of the poor.Footnote 24 Indeed, colonists coming to Drenthe voluntarily formed an exception: every year between 1830 and 1860 an average of just twenty-two families arrived of their own volition.Footnote 25 As far back as the early 1820s, the peat colonies relied extensively on state financing,Footnote 26 and in 1859 the colonies were taken over by the state, thus officially becoming a public institution. From then on, most of the thousands of families and individuals in the peat colonies were sent to or detained in the “beggars institutions” by local urban authorities. In 1875, 2,809 people were still living there, only ten of whom had volunteered.Footnote 27 Instead of transforming poor men, women, and children into hard-working citizens, the colonies had turned into a fully fledged penal institution, to which undesired elements from urban society were sent. Judged by their original intention, the peat colonies can thus be considered a failure. Nevertheless, an important effect of these social experiments was that they set an example for similar initiatives, both within and outside Europe.Footnote 28 More strikingly, the peat colonies formed a blueprint for the Cultivation System on Java, designed and implemented by their inventor Johannes van den Bosch when he was Governor General in the Netherlands Indies (1830–1833).

Much has been written about the Cultivation System, but for the purposes of this paper the relatively underexplored links with Van den Bosch’s benevolent colonies in the Netherlands are particularly interesting. Both can be seen as “development projects” with state support, focusing on the agricultural production of cash crops by the poor, who would not only work for their subsistence, but also receive a cash bonus for surplus crops. Moreover, in both cases the objective was to transform “lazy” paupers into industrious workers, and to this end a certain degree of coercion was tolerated.Footnote 29 Indonesian men especially were seen as idle, as opposed to their wives, whom the Dutch as well as the English portrayed as particularly industrious and entrepreneurial. For instance, Thomas Stamford Raffles, Governor General during the British interregnum in the East Indies (1811–1816), noted in 1817 that “[t]he labour of the women on Java is estimated almost as highly as that of the men”.Footnote 30 Indeed, early colonial officials in Java estimated that women spent about twice as much time on rice cultivation as men did.Footnote 31 Apart from subsistence agriculture (labour relation 4), which was presumably the most important labour relation on Java around 1800, both men and women performed communal agricultural tasks, as a sort of risk-spreading for the desa, the village community (labour relation 7), and they had to give part of their produce to the village head as a form of tribute (labour relation 8).

Van den Bosch stated that Javanese peasants needed to work only a few hours per day to survive. In order to make them produce also for the market, their industriousness needed to be enhanced, for their own benefit as well as that of the imperial economy.Footnote 32 To achieve this, Javanese peasants were expected to set aside a proportion of their land to produce export crops, such as coffee, sugar, and indigo, for the Dutch authorities. While peasants obtained monetary compensation for their production, this predominantly served to pay land rents to indigenous elites and Dutch civil servants. The system remained in place until around 1870, and although its effects varied greatly from one part of Java to anotherFootnote 33 it had tremendous effects on both the Javanese and the Dutch economies.

The effects of the Cultivation System on household labour in the Netherlands Indies, in particular on the work of women and children, are very much underexplored territory. Angus Maddison has concluded that the introduction of the system did not mean that Indonesian workers were impoverished, but that they had to work harder to meet their daily needs.Footnote 34 While Maddison did not explore the economic activities of Javanese women and children, my argument here is that their work did indeed increase. Ben White has recently stated that the Cultivation System “required fundamental reorganization of the household’s division of labour”.Footnote 35

Firstly, the labour input of women and children in subsistence agriculture increased, because men had to devote more of their time to cultivating cash crops. Although quantitative evidence is scarce, Peter Boomgaard has contended that in areas suitable for export crops the extra annual labour that was needed to fulfil the criteria of the Cultivation System was between 120–130 days per household.Footnote 36 This would have required women to devote more time to rice production, in which they had traditionally already been involved.Footnote 37 Thus, their activities in the form of subsistence labour (labour relation 4b) increased further.

Secondly, although this was explicitly not the intention of the authorities, women and children assisted or worked full time in the cultivation of cash crops as well.Footnote 38 Simultaneously, the labour-intensive production of second crops, for instance on garden plots, did not decline but increased during the Cultivation System, and Boomgaard has argued that this was an activity women tended to combine with their activities in the home.Footnote 39 Garden crops were sold mostly in the market, so the involvement of women in self-employed agriculture rose as well (labour relation 12b).

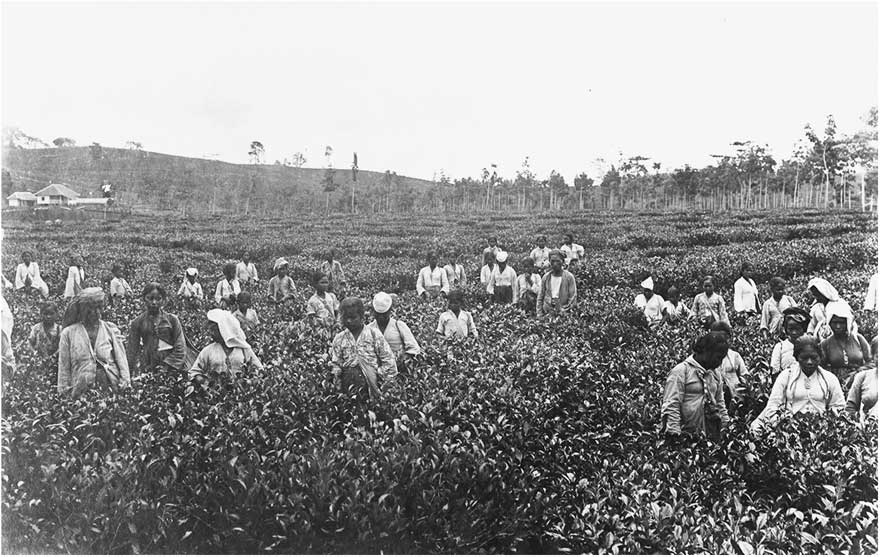

Thirdly, there is empirical evidence that women and children living in villages that were exempt from the cultivation duties performed free wage labour in neighbouring villages that were obliged to contribute, for instance by picking tea leavesFootnote 40 and on coffee plantations.Footnote 41 This means that the system also brought about a greater involvement of women and children in wage labour (labour relation 14). After 1850, wage labour opportunities, for instance on sugar plantations, increased even more – for men as well as for women.Footnote 42

This enhanced work effort by women and children, caused by a state-supported system of resource extraction, might have originated mostly out of increasing poverty, as Boomgaard argues.Footnote 43 However, other historians suggest that the colonial interactions also entailed new consumptive possibilities for Indonesian households. More generally, the rise of waged labour severely affected labour relations in the Javanese economy and households, as well as their consumption patterns.Footnote 44 In this sense, Van den Bosch’s initial aims – enhancing market production by the agrarian population – appear to have been more successful in the Netherlands Indies than in the Netherlands. Interestingly, in the Netherlands, Van den Bosch’s initiatives led to a (minor, because of the more modest scale of the “peat colonies”) shift in labour relations from non-working to mainly non-market economic activities, predominantly reciprocal labour in the form of penal work, whereas in the Netherlands Indies commodified labour relations were on the rise.

Without doubt, this difference in outcome related to the fairly effective grip the colonial state had on the Javanese economy. Ironically, this tight grip led to millions of guilders from the Cultivation System and other tax benefits flowing to the Dutch treasury during much of the nineteenth century (see Table 1).

Table 1 The “Batig Slot” (colonial surplus) from the Netherlands Indies, 1831–1877

Sources: 1831–1870: estimates by Van Zanden and Van Riel, Strictures of Inheritance, p. 180, including hidden subsidies. 1870–1877: J. de Jong, Van Batig Slot naar ereschuld. De discussie over de financiële verhouding tussen Nederland en Indië en de hervorming van de Nederlandse koloniale politiek, 1860–1900 (The Hague, 1989), pp. 133, 262; Jan-Pieter Smits, Edwin Horlings, and Jan Luiten van Zanden, Dutch GNP and its Components, 1800–1913 (Groningen, 2000), pp. 173, 177.

Especially after the 1850s and 1860s, when the surplus from the Netherlands Indies had been at its largest relative to the Dutch state’s tax revenues, male real wages started to rise spectacularly, and faster than in other Western European countries.Footnote 45 Moreover, compared to other European countries the registered labour force participation of women declined earlier and faster in the Netherlands, and this has often been related to the rising real wages of male labourers.Footnote 46 This rise in real wages was due not so much to higher nominal wages but to the reduction in excises, made possible in part because the Dutch treasury received a major share of its income from the colonies (see Table 1, last column). Of course, reducing indirect taxes on consumables was relatively favourable for the working classes, who had to spend a comparatively large share of their income on foodstuffs and fuels. As one historian has put it: “The surplus from the Indies enabled the government to lower the tax burden for the ‘common man’ without simultaneously raising it for the bourgeoisie.”Footnote 47 Althoughthe male breadwinner ideology was still far from being attainable for all working-class households, the development in real wages, which were closely linked to colonial remittances, most probably did create the conditions for a relatively widespread adoption of at least the ideal of the married woman at home. As I will argue below, this did not mean that married women stopped working. It did, however, entail a shift from work in formal wage labour and self-employment to more hidden and informal types of labour relations, such as performing wage labour activities in the home, which has often escaped the attention of officials and historians, and eventually, in the first few decades of the twentieth century, to a retreat into unpaid domestic tasks (labour relation 5).

Another effect of colonial economic policies on the Dutch economy in this period was rapid industrialization, which, in turn, affected the work patterns of households in the Netherlands. The semi-governmental Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij (Dutch Trading Company), established in 1824 by the Dutch king to monopolize trade with the Netherlands Indies, not only transported the cash crops gained from the Cultivation System on Java back to the Netherlands, it was also responsible for shipping cotton cloth produced in the Netherlands to the Indonesian market. To this end, new cotton factories were set up in the proto-industrial eastern provinces of the Netherlands.Footnote 48 Because of the increased monetization of the Javanese economy, Indonesian households shifted from home production of cotton to buying textiles imported from the Netherlands. On the one hand, mechanization caused the rapid decline of hand-spinning, seriously decreasing demand for homespun yarn among both Dutch and Indonesian women and children. On the other, it temporarily drew children and young women to the factories in the Netherlands, affecting wage labour relations in Dutch households.Footnote 49 In the late nineteenth century, especially in rural areas, Dutch wives and children accounted for twenty per cent of total household income on average. On top of this, their work in subsistence agriculture also contributed significantly to the family budget.Footnote 50

WORK, THE SOCIAL QUESTION, AND ETHICAL POLICY (1870–1901)

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the intensification of industrialization in the Netherlands and the social problems it brought about increasingly gained the attention of contemporary publicists and politicians. The labour of Dutch children and women formed an important aspect of the Social Question. Progressive liberals, in particular, started to debate the social consequences of industrialization, and they established their own societies and journals. Their attention was directed primarily towards the labouring classes, to prevent them from falling prey to the emerging labour unrest and socialism.Footnote 51 Nevertheless, some social liberals were also genuinely concerned about the miserable plight of many working poor, and they believed that the state should act to alleviate some of the worst injustices of industrialization. Although demanding social legislation was a bridge too far for these liberals, they agreed on legislation on one particular issue: child labour.Footnote 52 After fierce parliamentary debate, in 1874 Samuel van Houten, one of the progressive liberals active in these circles, succeeded in getting his Child Labour Act (Kinderwetje) passed, which prohibited industrial work for children younger than twelve. Though far from comprehensive, it constituted the very first piece of Dutch labour legislation.

Apart from child labour, women’s work – and especially married women’s work – was on the agenda of bourgeois efforts to civilize society. One of the goals was to transform married women from the labouring classes into devoted, neat, and frugal housewives, who would lay the foundations of a stable family life, preventing disorderly behaviour such as alcoholism by their husbands or vandalism by their children. Being a proper housewife was thus incompatible with full-time work outdoors.Footnote 53 In the 1880s, such private initiatives also gained political weight. Both the women’s movement and the emerging liberal, confessional, and social democrat political parties started to get involved in the debate on labour. Their discussions concerned not only the need to protect women and children against exploitation, but, more fundamentally, the suitability of married women for work, both on physical and moral grounds.Footnote 54 These concerns led to the 1889 Employment Act, containing regulations against “excessive and hazardous labour by juvenile persons and women”. Among other things, this law restricted the working day for women and children under sixteen to a maximum of eleven hours, and prohibited Sunday and night labour for these groups.Footnote 55

During this period, a particular socio-political context had developed in the Netherlands that historians have termed “pillarization”. From the 1870s onwards, interest groups emerged organized according to ideology (Catholic, orthodox Protestant, or socialist), establishing associations and organizations in many societal domains. The “pillars” had to collaborate with each other and with the less organized “rest” (liberals and non-orthodox Protestants) because no single group could obtain a political majority. This led to a transformation in the direction of society, from a more liberal to a more “neo-corporatist” tendency, in which all the pillars were to resolve as many of their problems as possible within their own group, with minimal public support. In this new order, the Social Question had a distinctive place. The elites among the newly organized confessional groups – orthodox Protestants and Catholics – in particular, but also the socialists, adopted the strategies of civilizing the working classes that had already been adopted by the liberal bourgeoisie.Footnote 56

Indeed, confessional politics became increasingly important in constituting some form of social security towards the end of the century. With increasing industrialization, the labourer had gained a more important role in the economy and society, and this was also reflected in contemporary theological ideas about labour. Instead of being a curse for sin, originating in Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden, manual labour was increasingly seen as virtuous (at least for the lower social strata). Modern theologians depicted labour as the driving force behind the societal and economic progress that was God’s will. On these grounds, ministers and confessional politicians would have to convince the labouring classes that they should not contest their position through strikes or work stoppages,Footnote 57 that their superiors ought to promote their best interests, and that the state should set some minimum conditions for monitoring labour protection. To this end, the orthodox Protestant politician Abraham Kuyper had already made quite revolutionary propositions in parliament in 1874, but the time was not yet ripe.Footnote 58 Only fifteen years later, the 1889 Employment Act, with its restrictions on women’s and children’s work, was introduced by the very first Christian administration in the Netherlands, a coalition of Catholics and orthodox Protestants.

Some historians have defined this particular socio-political culture, in which the elites of the diverse pillars aimed to promote the best interests of their less fortunate followers, as “patronizing citizenship”.Footnote 59 As the historian Elsbeth Locher-Scholten showed in 1981, this specific Dutch political culture may likewise help explain the development of a changing attitude towards the Netherlands East Indies in this period.Footnote 60 Politicians and social commentators became increasingly aware that the excessive financial revenues derived under the Cultivation System and, after its abolition, the huge tax revenues derived from the Netherlands Indies, had negatively affected the financial state of the Netherlands Indies. The devastating consequences for the welfare of the archipelago and its native inhabitants increasingly raised the indignation of several contemporaries. In a famous article, publicist and lawyer Conrad Theodor van Deventer pleaded for this “debt of honour” (eereschuld), which ran into millions of guilders, to be repaid and invested in the well-being of the population, for instance by providing basic education and improving infrastructure.Footnote 61

In the spirit of the age, the second confessional administration of the Netherlands, led by the Protestant Kuyper, implemented the Ethical Policy in the Netherlands Indies at its inauguration in 1901. In her annual speech to parliament, the young Queen Wilhelmina stated that “the Netherlands was to fulfil a moral calling towards the population of these provinces”.Footnote 62 As Kuyper had already declared in “Our Programme” in 1879, his Anti-Revolutionary Party aspired to a form of “custody” over Dutch overseas possessions, rather than exploitation or colonialism. This custody was to be achieved by the moral uplifting of indigenous populations, in the first place by Christianizing them.Footnote 63 The Ethical Policy had two main objectives: improving the welfare of the indigenous population and, at the same time, increasingly subjecting them to the colonial state. This policy followed from the fact that, as a Christian nation, the Netherlands had a duty towards the indigenous inhabitants of the East Indies. This entailed missionary work, the protection of contract labourers, and a general investigation into the “lesser welfare” of the Indonesian population.Footnote 64 This attitude towards the common indigenous people had striking similarities with the attempts made in previous decades at civilizing the working classes in the metropole. According to the Anti-Revolutionaries, the labouring classes in the Netherlands also had to be morally uplifted, and protected in ways that resembled practices of custody.Footnote 65 Another parallel was that responsibility for their living standard was no longer placed solely on the working poor, and that society and – to a limited degree – the state ought to create vital minimum conditions for its population’s welfare, both in the metropole and the colony.

One element of the Ethical Policy was a focus on Javanese households, and particularly the place of women. In some sense, concerns about the position of married women in the Netherlands Indies and their working activities mirrored those about Dutch housewives, but apart from class, ethnicity invigorated paternalism. As noted above, the traditional image of the Javanese woman was that she was very active, both within the household and in the labour market, in contrast to her husband, “the average coolie, who does not work unduly hard”.Footnote 66 Around 1900, the general image of the Javanese woman was still that “[s]he toils and drudges as long as her powers allow her to”.Footnote 67 Nevertheless, European notions of the role of Indonesian women had become more differentiated in the course of the nineteenth century. This was due partly to the more intensive encounters between Javanese and Dutch people, the latter having increasingly settled (with their families) in the colony. Partly, however, these new ideas were related to increasing concerns in the Netherlands about the standard of living of the indigenous population. Indonesian women were regarded as important actors in the civilization offensive this new attitude entailed.Footnote 68

Like almost a century earlier, the industriousness of the Javanese population was considered important, but the newest insight on this issue was that the loose family ties on Java supposedly led to a lack of diligence and entrepreneurship, thus hampering the region’s economic development. To strengthen these ties and guarantee a more stable family life, the wife needed to function as the centre of the household, and it was recommended that she withdraw from the public domain.Footnote 69 Furthermore, Christian missionaries tried to impose “Western” family norms on the households they converted. Their attention was initially directed towards combatting polygamy and convincing Indonesian women that their most important role was to be a housewife and mother, whose primary obligation lay in their household duties.Footnote 70

However, ideal and practice were far apart. For one thing, large differences continued to exist between various social groups. The two lowest – and largest – groups in society were the poor and “common” desa-vrouwen (village women). From an early age, they helped their parents in the fields, or watched over their younger siblings. After marriage, they usually continued to work hard on the land or in their own small business, “since only few women are being sufficiently sustained by their husbands”.Footnote 71 Moreover, they were traditionally active in all kinds of industries, including hand-weaving, which continued to be of importance until the 1920s, food processing, and woodworking, such as the plaiting of bamboo and rattan.Footnote 72 There were also the santri women, Muslim women generally from the middle classes who received some form of religious instruction and who usually became obedient and thrifty housewives. Finally, there were the priyayi (elite) women, often highly educated and wealthy, who usually outsourced their domestic tasks and were considered lazy and extravagant by Dutch observers.Footnote 73

These are, of course, all stereotypes, but my point is that the rhetoric with regard to Indonesian women continued to revolve around their industriousness (or lack of it). The promotion of Western family values in the Netherlands Indies most prominently affected the role of priyayi and Christian women, who were of course minorities in a society largely consisting of Muslim small farmers. However, both economic interests and racist prejudices were too entrenched to allow the cult of “domesticity” to extend to include the majority of women, non-Christian desa women, whose labour would actually become more important, as we will see in the next section. As opposed to the communis opinio on Dutch women, the idea that Indonesian women should not be performing work outdoors at all was uncommon. Unlike in the metropole, satisfactory protective labour legislation and education for indigenous women and children were not yet considered necessary in the colony.

FURTHER LEGISLATION AND THE “MALE BREADWINNER SOCIETY” (1901–1940)

Not only in the Netherlands Indies, but also in the Netherlands, ideology and practice sometimes diverged. The 1874 Child Labour Act, for instance, covered only industrial labour by children up to the age of eleven, and the agricultural and service sectors were long exempt from regulation. The 1889 Employment Act, too, made exceptions, for instance for Sunday work for women in dairy processing. Also, even after the Kuyper administration had enacted the first law on compulsory schooling for children aged up to twelve, many children stayed at home, for instance to help on the family farm, especially in seasons when their labour was dearly needed.Footnote 74 In the early 1920s, just after the minimum age for child labour had been raised to fourteen years, many parents complained to the Labour Inspectorate that this law obliged their children to remain at home idle for two years: they no longer had to go to school, but they were not yet allowed to work.Footnote 75 The archives of the Labour Inspectorate show that, despite society’s changing norms, child labour was still very much a feature.Footnote 76 As late as 1928, for example, the Director General of Labour, C. Zaalberg, complained: “in industrial centres one sees the questionable phenomenon of housefathers being unable to find work and living off the earnings of their daughters”.Footnote 77

Likewise, work by married women had not completely disappeared by the beginning of the twentieth century. Although the official censuses show a clear decline in the participation of women in the Dutch labour market, particularly in the category of registered gainful employment by married women, part of this decline must be ascribed to under-registration of wives who worked in the family business or in domestic industry.Footnote 78 In the 1910s, a study and exhibition focused attention on the situation in Dutch domestic industry, in which many women and children worked part-time. It is hard to estimate their numbers, in part owing to shortcomings in the study, shortcomings that the Director General of Labour at the time, H.A. van Ysselsteyn, acknowledged.Footnote 79 We do know for certain, however, that many women performed paid work at home, rolling cigarettes, wrapping sweets, and canning vegetables for example. Interestingly, these women also produced for the colonies. They made trimmings for sale in the Netherlands Indies, but sometimes also fabricated military accessories, such as badges and “embroidered grenades”.Footnote 80

Figure 2 Postcard promoting that mother’s place is in the home, not in the factory. Katholiek Documentatie Centrum Nijmegen. Used with permission.

Still, the male breadwinner model had already taken root in the Netherlands by the turn of the twentieth century. For instance, the official participation rate of women older than sixteen had declined from twenty-four per cent in 1849 to seventeen per cent in 1899, which was very low compared with other Western European countries at the time.Footnote 81 Because under-registration was a reality in other countries as well, we can safely conclude that women’s participation was comparatively low in the Netherlands around 1900.Footnote 82 Moreover, the percentage of married women with an occupation recorded in the census was only slightly over four per cent, which is low however you look at it.Footnote 83 An increasing proportion of the female population had thus either switched to performing economic activities in the home, either as wage earners or self-employed (labour relations 14 and 12b respectively), or were able to become full-time housewives (labour relation 5).

Also, the first few decades of the twentieth century witnessed further legislation in an effort to reduce the participation of children in the labour market and, perhaps more importantly, keep them in school longer (see Table 2).

Table 2 Legislation on child labour and schooling, 1901–1921

Source: Based on Smit, Fabriekskinderen, p. 11.

Further labour legislation in the Netherlands in this period again targeted women’s work. In 1937, the conservative Catholic Secretary of State Carl Romme even proposed legislation to prohibit all work by married women. Eventually, his bill was watered down to apply only to female state employees. The documents drawn up by the committee preparing the bill provide interesting information on the discussions between conservative, confessional, liberal, and socialist members, most of whom did not disagree so much on the “true calling” of the married woman, but on the question of whether the state ought to prescribe this ideal or leave it up to households themselves.Footnote 84

In the Netherlands Indies, developments were very different. As we know, the work of married women outside the household and family farm, for instance as wage labourers on tobacco or rubber plantations, was perhaps frowned upon, but it was never intended to be eradicated. The lobby of important businessmen and plantation owners, making widespread use of “cheap and compliant” labourers, was simply too powerful. Many sugar and coffee plantations employed not only indigenous men, but also their wives and children. A sample of 400 plantation workers shows that, on average, seventy per cent of their wives also worked independently of their husbands for wages in all kinds of manual agricultural labour, accounting for an average of almost thirty per cent of household income.Footnote 85 Thus, although ever since the introduction of the Ethical Policy the advantages of the role of women as a stable factor within the household had been stressed, economic incentives to employ them outside the house were too strong. Moreover, as many plantation owners allowed whole households to live on the plantation, they perhaps thought they could hit two birds with one stone.

Figure 3 Women picking tea leaves for the Tjimoelang tea company at Buitenzorg. Collections KITLV. Used with permission.

A similarly ambivalent attitude towards the work of Indonesian children prevailed. As we have seen, work by children, especially under the age of twelve, had been a matter of growing concern and intense debate in the Netherlands in the second half of the nineteenth century, with legislation being introduced in 1874. In contrast, a total disregard for the issue prevailed in the Netherlands Indies. Interestingly, while the minimum age for child labour in the Netherlands had been raised to fourteen in 1919 (see Table 2), in 1926 it was set at twelve for Indonesian children. This becomes clear moreover if we look at school enrolment rates. By 1900, ninety-five per cent of all Dutch children younger than twelve attended school, whereas only 0.5 per cent of all Indonesian children received schooling.Footnote 86 As part of the Ethical Policy, from around 1900 the colonial government increasingly invested in a schooling system for indigenous children. However, this was a highly hierarchical system, with “European” schools being accessible only to children from the elites, “standard” schools aiming at middle-class children, and desa (village) schools being visited mainly by children from lower social groups. Although the indigenous schooling system was in principle open to both boys and girls, it was meant primarily to provide boys with the necessary education to enable them to maintain a family, or – for the higher classes – to prepare them for a career within the colonial administration. Moreover, most indigenous parents objected to their daughters being in the same classroom as boys.Footnote 87 These obstructions are reflected in reported school enrolments rates for the period 1909–1922, which indicate that girls constituted only about eight per cent of the total number of pupils.Footnote 88 Likewise, the scarce data available on literacy rates also reveal low family investment in the education of girls: according to the 1930 census only 2.2 per cent of indigenous women could read and write, while 10.8 per cent of indigenous men were registered as literate.Footnote 89 Among Dutch officials and citizens, this was not perceived as a problem, and it was believed that educating a small number of priyayi women would suffice to disseminate knowledge and values further to ordinary women (desa women or volksvrouwen).Footnote 90

From the 1920s onwards, the issue of restricting female and child labour in the colony was increasingly debated in the Dutch parliament following severe criticism by the international community of Dutch reluctance to implement legislation restricting female night work and child labour in the Netherlands Indies. In 1926, the International Labour Office (ILO) called on the Netherlands to introduce labour legislation in the colonies. The 1930 census of Java and Madura lists almost thirty per cent of all married women with a registered occupation, predominantly in agriculture and industry. Compared with the low official figures for the Netherlands (where only six per cent of all married women were recorded as having an occupation in 1930), this percentage was very high.Footnote 91

To give an impression of the type of work Indonesian women and girls performed, I have listed the five occupations most frequently reported in the 1930 Census, both for married and unmarried women. Not surprisingly, given the agrarian nature of Javanese society at that time, most women worked in small-scale agriculture. However, compared with Indonesian men, a much larger proportion of women with an occupational record worked in the industrial and service sectors, most notably in food and textile production and retailing. For unmarried women, domestic service was quite common (see Table 3). It should be noted, however, that, like the Dutch census, the Netherlands Indies census registered only what the authorities considered to be “gainful employment”: those types of labour that generated “compensation (be it in money, or in kind), [excluding] mere refreshments”.Footnote 92 Thus women working in subsistence agriculture (labour relation 4b) or performing communal agricultural services (labour relation 7) were not included in the statistics.

Table 3 Five most frequently recorded occupations for married and unmarried women, Java and Madura, 1930

Source: CBS, Volkstelling 1930, Vol. III, pp. 94–95.

Proponents of work by Indonesian women and children stated that indigenous culture and traditions made women’s hard physical labour customary, and that children were better off working than being idle.Footnote 93 These opinions were voiced primarily by Western entrepreneurs and liberal politicians, who viewed Indonesian women and children as a source of cheap labour and opposed state intervention. But it was not only the business community that stressed the inherent differences between Dutch and Indonesian women. In 1925, publicist Henri van der Mandere wrote:

It is self-evident that women in Western society are excluded from hazardous and tough labour […]. Women’s position in Indonesian society is incomparable to that of the Dutch woman. Whereas manual labour is an exception in the Netherlands, it is the rule here; there are even regions where it follows from adat Footnote 94 that almost all work is done by women.Footnote 95

This quote indicates that it was not only considered “natural” for Indonesian women to work, the inherent differences between Indonesian and Dutch women also made it self-evident that the latter were to be protected from hazardous work. This is a fine example of what Ann Stoler and Frederick Cooper have called “the grammar of difference”.Footnote 96

CONCLUSION

This article has analysed the role of the state as a regulator and arbiter in changing labour relations, focusing on the work of women and children from the perspective of the colonial connections between the Netherlands and the Netherlands Indies. During the nineteenth century, the Dutch state increasingly intervened in social affairs, both in the metropole and the colonies. I have shown that the principles underlying changes towards further interventionism were quite similar in both parts of the empire at least until the end of the nineteenth century. However, the scope and effects of intervention differed tremendously in the Netherlands and the Netherlands Indies. The explanatory framework I have used for this “simultaneousness of the non-simultaneous” is the different ideological attitudes towards the working classes in the Netherlands and the Netherlands Indies, which seem to have further diverged in the course of the nineteenth century. In the early nineteenth century, combatting idleness and encouraging the poor to work was still on the agenda in the metropole as well as in the colony. In fact, it may be stated that Dutch elites tended to view the working poor in the Netherlands as “a foreign country” almost as much as they did the Javanese commoners. Thus, similar initiatives were taken in 1818 and 1830, respectively, to reform the population’s labour ethic, not coincidentally by one and the same man, Johannes van den Bosch, and supported by King William I.

Apart from their initiator, there were several other striking parallels between the peat colonies of the Maatschappij van Weldadigheid and the Cultivation System. Both were state-supported, focusing on raising market production in the agricultural sector. In both projects, the objective was to educate “lazy” paupers in order to transform them into thrifty workers, and a high degree of social engineering, and even force, was occasionally used. Also, in both cases it was expected that women and children would contribute to the family economy, although most commonly on the family farm. A major difference between the two initiatives was their scope: although several thousand Dutch families went to the peat colonies, it remained a peripheral phenomenon, and from the beginning many workers considered it to be a penal colony, which it would eventually turn into. Conversely, the Cultivation System would have tremendous effects on Javanese society and labour relations there. Moreover, at the same time, as I have argued here, the gains from the Cultivation System and other extractive colonial policies influenced economic development and labour relations in the Netherlands.

Important effects on the Javanese economy included rapid monetization, and an increased workload by women and children, in subsistence agriculture but also in self-employed and waged labour. The role of women in subsistence agriculture had traditionally been large, but the forced shift by men towards cash-crop cultivation made this role increasingly important. More importantly, the monetization and commodification of the entire economy, in which the Cultivation System played a decisive role, increased opportunities for women to sell their products in the market or to perform wage labour on plantations or for neighbours. Simultaneously, the state-subsidized imports of Dutch textiles into Java stimulated the take-off of industrialization in the Netherlands, especially in traditional proto-industrial areas, where the factories were looking primarily for cheap wage labourers, such as young children and women. While in a totally different – urbanized and industrializing – context than in the Netherlands Indies, this did initially (up to about the 1880s) raise the proportion of young as well as married women in the labour force. However, simultaneously, a counter effect was achieved by the enormous flows of capital from the trade in Javanese cash crops, and other taxes, into the Dutch treasury. These cash flows allowed for excise reforms in the metropole, contributing directly to a rise in male wages, implying the foundation of the financial realization of the breadwinner–homemaker ideal for an increasing number of households in the Netherlands. Even though for most working-class households this goal became attainable only in the first few decades of the twentieth century, from the last decade of the nineteenth century it motivated married women to switch from labour outside the home to economic activities in the private sphere.

In the same period, industrialization and the growing importance of wage labour, as well as the “pillarization” in which class distinctions in the Netherlands were partly overruled by ideological differences, led to a different take on the position of work and labourers in the metropole. Although the Social Question was born primarily out of concerns about labour unrest, a growing number of contemporaries were genuinely worried about the well-being of the lower classes. This apprehension was further induced by the rise of confessional parties from the 1870 onwards; they were not opposed to a mild form of state regulation, and even legislation. Though the 1874 Child Labour Act had been drawn up by a liberal, even at the time some Protestants, such as Kuyper, believed it did not go far enough.

While civilizing the working classes was not a confessional prerogative – it was an objective shared by liberal and socialist elites alike – the Christian parties gave it their own twist. Gender played an increasingly important role in the debate after the issue of work by very young children had been resolved by the 1874 legislation. The moral concerns regarding men and women working together in factories, and particularly the central role of the clean and thrifty housewife within the labouring household, were central issues in the debate. Throughout the entire period, we can observe a shift among married women from wage and self-employed labour to more informal paid work and subsistence agriculture around 1900, and subsequently to the status of housewives (labour relation 5) by the late 1930s.

Christian values also played a role in the development of the Ethical Policy in the Netherlands Indies, symbolizing the moral responsibility towards the underdeveloped population of the archipelago. The Ethical Policy followed from a broader discontent that had been growing under the Dutch elites, due to the increasing realization that the Dutch state and economy profited immensely from the gains made from the colony, and that the indigenous population suffered from this extraction. However, after its implementation, the Ethical Policy was concerned primarily with the Christian mission and with definitively making the Javanese subjects of the Dutch state. Although according to the ethical rhetoric Indonesian women were crucial in modelling indigenous family life according to “modern” Western values, in practice the labour of women and children – especially for the lower classes and farmers – was not explicitly opposed, or even protected against. Moreover, the ideals of domesticity would not have been as financially attainable as they were in the metropole, simply because the taxes and profits drained from the colony were too high to allow higher living standards for the majority of the indigenous population. Only a small minority, comprising elite and higher middle-class Indonesian women, could afford to adjust to live up to “Western” ideals of domesticity.Footnote 97

Unlike the Dutch working classes, Javanese households thus remained “a foreign country” to the elites in the Netherlands. While labour protection as well as education became increasingly available to Dutch women and children in the beginning of the twentieth century, these provisions were scarcely extended to their Indonesian counterparts. Conveniently, within the context of the decline of coerced labour on Java, women and children formed a source of cheap labour that entrepreneurs in the Netherlands Indies wished to employ. Until well into the 1920s, politicians and contemporary observers utilized a rhetoric of innate culture and traditions, not only to legitimize the absence of social legislation in the colony but also to stress that these inherent differences justified the fact that Dutch women and children were indeed protected by law. Moreover, whereas in the Netherlands there was a state body to counteract possible excesses (the Labour Inspectorate), no such institution had been set up in the Netherlands Indies, and ultimately the ILO had to monitor the implementation of social policies in the Dutch colony. A “grammar of difference” moulded the state’s intervention, in the colony as well as the metropole.