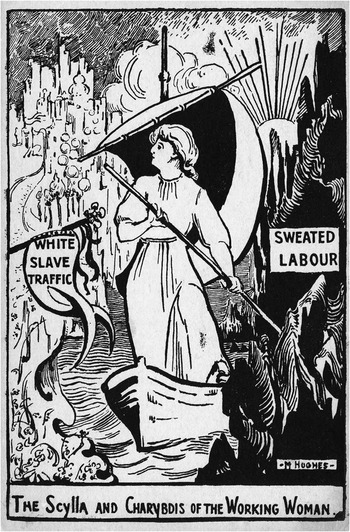

A multitude of images were produced in the early twentieth century on the “white slave traffic”, or “white slavery”. This popular iconography helped to create the idea that sex trafficking was a phenomenon in which passive and innocent victims were kidnapped from the safety of their work or their homes and exploited and abused in prostitution. In these depictions, white faces peer from behind bars or implore the viewer with clasped hands, while racialized “white slavers” lurk in the background.Footnote 1 Amid these images, a postcard produced by the London-based Suffrage Atelier in 1912 is striking in its unique presentation of the problem of the white slave traffic (Figure 1). In it, a woman attempts to navigate her small craft through dangerous waters, caught between what the postcard calls “the Scylla and Charybdis of the Working Woman”: “white slavery” and “sweated labour”.Footnote 2 No kidnapper is in sight. The woman is looking away from the jagged black rocks of Scylla, representing the long hours and poor pay she would get from the feminized “sweated industries”, such as matchbox making, garment finishing, and laundry and char work. She turns slightly towards Charybdis, a whirlpool whose foam reveals the alluring and exotic spires of a city, which represents a life in prostitution. She does not passively implore the viewer to save her. She is too busy actively attempting to avoid both the rock and the hard place. It is a remarkable break from typical representations of exploited prostitution.

Figure 1 ‘The Scylla and Charybdis of the Working Woman’, Suffrage Atelier, London c. 1912. Source: LSE Women’s Library’s collections.

Historians of prostitution, women’s work, and migration have long recognized the realities of “the Scylla and Charybdis” of working women in this period, and broadly acknowledge that prostitution was deeply connected to women’s labour.Footnote 3 Recently, historians have also begun to consider the phenomenon of “white slavery”, or “trafficking” in greater depth. The oldest and largest part of this scholarship has focused on the way in which the discourse of “white slavery” reproduced images of women involved in prostitution as passive, sexually innocent, and racially white victims. This work has shown how policies and attitudes surrounding trafficking and “white slavery” helped to draw the literal and figurative borders of the “nation”, and became a way to police (especially) female and non-white sexuality more broadly.Footnote 4

Other historical work on sex trafficking has examined the international or transnational dimensions of the campaigns surrounding the phenomenon, which first began in the late nineteenth century and gained new strength through the League of Nations in the interwar years. From these perspectives, the anti-trafficking movement is an important moment in the history of internationalism. Some scholars, such as Barbara Metzger and Daniel Gorman, approach this internationalism from a positivist perspective, seeing the campaign against the traffic in women as a key development in a wider story of the move toward an international human rights regime and campaigns for “social relief”.Footnote 5 This remains the dominant understanding of the history of campaigns against trafficking, and it is how present-day international and philanthropic efforts have likewise been described.

In his study of the international campaigns surrounding trafficking, Paul Knepper is less sanguine. He argues that, above all, the historical anti-trafficking movement was about crime control rather than relief or rights.Footnote 6 Other scholars, such as Magaly Rodríguez García, Jessica Pliley, Eileen Boris, and Stephanie Limoncelli, delve more deeply into the ruptures and contradictions of international anti-trafficking campaigns, questioning their portrayal as human rights interventions, as part of a unified feminist movement, or as successful social reform.Footnote 7 Of these, Rodríguez García and Boris have been the most concerned with the intersections of trafficking and women’s work. Both argue that the League’s Advisory Committee on the Traffic in Women and Children opted to examine the moral welfare of women rather than focus on conditions of work. As Boris puts it, they were focused on “protecting virtue” for vulnerable migrant women while “erasing” their labour from the analysis of trafficking.Footnote 8

In this article, I hope to elaborate on and complicate Boris’ brief analysis of the way that work was erased from the discussions of prostitution and trafficking in the League. While I consider the international dimensions of discussions on trafficking in this analysis, I also respond to calls for more national context in explorations of trafficking discourse and policy.Footnote 9 I will examine anti-trafficking discourse and policy in the British domestic context, which is both a particular and neglected side of the history of trafficking and women’s exploited labour. Britain was a major site of in- and trans-migration, and the policies that emerged in a national context reverberated around – and responded to – the wider British world, even if British officials remained myopic about the nature or even existence of trafficking within the empire. Markedly different from the US, and likewise from the Continent, the British context is also important because of its position as a world leader in developing ideas and policies about trafficking even if, as in the US, Britain struggled to act within the parameters of trafficking that they had haphazardly helped to define.

This article uses the British example as well as an analysis of the international context, to explore the discursive and practical entanglements of women’s migrant labour and sex trafficking in the interwar years, which witnessed the dissolution and reformation of key organizational bodies and important changes both in immigration law and in geopolitical labour realities. I will first briefly explore the complex history of terms such as “traffic” and “white slavery” within a nexus of global work as well as ideas about race and sexuality. I will then examine discussions about trafficking and women’s work in Britain and internationally in the interwar years, a period that was instrumental in codifying modern national and international conceptions of “trafficking”. I argue that during this period, porous and faulty borders were drawn between sex work, women’s licit work, and their sexual exploitation and their exploitation as workers. These borders were at their thinnest in discussions about two important sectors of female-dominated migrant labour: domestic and care work, and work in the entertainment industry.

The legacy of the borders that were built between migrant sexual labour and other migrant female labour has cast a long shadow indeed, but it has also created lasting confusions, contradictions, and shortcomings in anti-trafficking policy. This period, which was so crucial to establishing the dominant discourse on trafficking in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, witnessed a move away from a more holistic vision of trafficking as part of a wider story of migrant women’s sexual, economic, and social oppression to one in which trafficking was a specific phenomenon linked to sexual vulnerability, illegal migration, and criminality. To be sure, many socialist and radical reformers continued to critique prostitution, and, to a lesser extent, trafficking, as a facet of a much wider problem of exploitation. Their efforts to do so bear further scrutiny; however, they are not the focus of this article, which attempts to explain why these perspectives did not prevail in either national or international debates and policy. The early twentieth century campaigns against trafficking increasingly severed the connections between work and prostitution, and between ordinary migration and trafficking. The anti-trafficking movement, alongside the international labour movement, attempted to separate sexual labour from other forms of labour, and in doing so wilfully ignored or suppressed moments when they obviously intersected and downplayed the role of other exploited and badly-paid licit work that sustained the global economy. In turn, the British state responded to this simplified vision of trafficking with half-hearted measures, focused mainly upon crime and migration control rather than labour legislation.

Yet, trafficking – including sex trafficking – has always been about work, no matter how much some campaigners, international officials, and states in this period did not want it to be or tried to pretend it was not. The discursive and legal divisions that were drawn up between women’s migrant labour and sex trafficking in the first half of the twentieth century were therefore carefully cultivated, but often unsuccessful. Those appointed to discuss and solve the problems associated with women’s trafficking and women’s labour found themselves caught between their own Scylla and Charybdis: despite their careful navigations, work kept finding its way back into discussions of sex trafficking, and trafficking remained entangled with the realities of women’s work.

Sex Trafficking and Labour Exploitation

The history of work and labour exploitation permeated the terms that were used to describe the exploited and migrant prostitution of women. Indeed, the term “white slavery” was first employed in Britain to describe the chattel slavery and indentured servitude of white people in North Africa in the seventeenth to early nineteenth centuries, and white slavery was deployed in the mid-nineteenth century to criticize the government’s policy of sending (mostly male) colonists to Van Diemen’s Land. Mid-century “white slavery” could also refer to children working in England’s “satanic mills”, or Italian organ grinders on the streets of London. As historians Gunther Peck, Mara Keire, and Eileen Boris note, the labour movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries used the term “white slavery” to describe the exploitation of white workers, especially in clothing manufacture, heavy industry, and agriculture.Footnote 10

White slavery as a concept had a “historical plasticity”, as Peck puts it, which is often not acknowledged by historians, who are primarily concerned with “white slavery” as a form of prostitution or an instance of moral panic. In Trafficking and the Transformation of Journalism, Gretchen Sonderlund develops a more nuanced view: she argues that William Stead, in his internationally resonant campaign against child prostitution in “modern Babylon”, changed the term “white slavery” from a “polysemic term that encompassed a number of meanings” (polygamy, indentured servitude, wage slavery, the working conditions of factory and shop girls, the southern pro-slavery mindset, etc.) to “congeal around the notion of forced domestic and international prostitution”.Footnote 11 Peck argues that the concept was “feminized” in this period, moving away from its connections with labour and becoming more firmly associated with exploited prostitution. Keire, meanwhile, notes the way in which that same separation from the labour movement helped to privatize the idea of white slavery, shifting the responsibility for exploitation from the state (and its control of labour) to the private enterprise that was the sex industry. Both Peck and Keire work with American sources, and, as Peck suggests, this shift to a more feminized and criminalized vision of white slavery occurred far earlier in Britain than it did in the US.Footnote 12 In fact, “white slavery” appears to have completely lost its salience for the British labour movement by the turn of the century.

By the interwar years, as many historians have also observed, the term “white slavery” was rejected by the international campaign and replaced with “the traffic in women and children” in order to reflect the fact that sex trafficking could happen to non-white women as well.Footnote 13 However, using “trafficking” instead of “white slavery” complicated but did not sever the term’s ties to other kinds of exploited labour. Trafficking emerged as a term and a concept during a period in which both migrants and workers were being redefined. Migration historian Adam McKeown argues that the modern concern about trafficking could only have emerged in the way it did in the nineteenth century because of that century’s redefinition of what a migrant was. As McKeown notes, before the mid-nineteenth century, “most long-distance labour migration was made possible through borrowed money, indenture contracts or slavery”.Footnote 14 By the later nineteenth century, thanks, in large part, to the movement to abolish slavery and the development of a global “free” labour market, a new understanding of free and unfree labour had emerged that, according to McKeown, “still shapes understandings of migration and labour to this day”. But there remained fundamental shortcomings in “the free and unfree dichotomy”, which “could not account for the multiple forms of obligation and debt that actually supported most migration”.Footnote 15 Meanwhile, the worker – who was increasingly a migrant worker – also continued to be more carefully defined by the transnational institutions of this period, who were interested in clearly delineating free labour from what they considered to be the pre-modern, and un-Western modes of labour like indenture, debt bondage, and slavery.Footnote 16 Within this discussion, as Eileen Boris’ forthcoming book on “the making of the woman worker” explores, women’s labour emerged as a particular problem, which I will elaborate below.Footnote 17

It was onto these insistent but highly imperfect dichotomies of free and unfree work and migration that newer ideas about “white slavery” and “sex trafficking” were grafted. Indeed, as Sunderland concludes, “white slavery” remained a “slippery, ambiguous, and imprecise term”.Footnote 18 Even as the idea of white slavery and trafficking became more feminized, criminalized, and stable in the very early twentieth century, feminists and socialists continued to connect prostitution to women’s work and trafficking to women’s migrant labour. Many different campaigners in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries understood prostitution as part of a larger spectrum of women’s exploited labour under capitalism, which was itself tied to heated debates about the nature of indenture, contract, and “free labour” in this period.Footnote 19 “The wages of prostitution are stitched into your button holes”, wrote the Fabian socialist George Bernard Shaw, in his scathing critique of the campaigns to pass the Criminal Law Amendment (White Slavery) Bill in the United Kingdom in 1912. Only the “abolition of industrial slavery”, wrote the anarchist feminist Emma Goldman in the United States the year before, would see the abolition of exploited prostitution.Footnote 20 It is clear that “white slavery” and trafficking, as it came to be known, had a much older history related to race, mobility, and exploitation that was not simply replaced, but rather overlaid with and further complicated by the new late nineteenth-century conceptualization of white slavery as related to gender, sex, and prostitution.

In light of these widespread critiques, and considering the deeply entangled history of “trafficking” and migrant labour, the reluctance of international campaigns, and national policies against trafficking to include discussions about women’s labour appears far from normative. Given the long-standing feminist and socialist critique of women’s exploited labour and prostitution that had been articulated by reformers since the mid-nineteenth century, illustrated no more clearly than in the image of the working woman in the postcard above, and given the role that these reformers played in the formation of anti-trafficking campaigns and campaigns for workers’ rights, why did these ideas come to hold so little traction in the national and international policies that emerged from them? The local and radical campaigns that continued to emphasize the links between work and prostitution were exceptionally unsuccessful in influencing policy nationally or internationally in this period, but their existence shows that the refusal to connect women’s work to migrant prostitution on the international stage or in national policy was not a matter of natural consensus. It was, instead, a carefully constructed omission; this silence speaks volumes.

Trafficking and Women’s Labour on the International Stage

The International Labour Organization (ILO) was established in 1919 as an agency of the League of Nations, dedicated to securing “justice and humanity” for the world’s workers in order to prevent the spread of communist revolution and labour unrest. Much of the groundwork for the ILO’s mandate and mission had been laid prior to World War I, as part of the socialist, reformist, and internationalist drive of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 21 The League of Nations also formed an Advisory Committee on the Traffic in Women and Children in 1921 (hereafter AC or Advisory Committee), which, like the ILO, had late-nineteenth-century roots. The aims and conventions of the AC as well as the organizations and individuals who were involved, were directly connected to the international campaign against white slavery and the conventions it put in place prior to World War I. As scholars such as Pliley, Limoncelli, Knepper, and Jean-Michel Chaumont have argued, the Advisory Committee, and the international campaign more broadly, was riven with competing ideologies, controversy, and fundamentally irreconcilable positions: between those who supported, roughly, the regulation of prostitution and laws of exception against prostitutes and young women (such as their forcible repatriation, or the limitation of their movement for their own protection), and those who were staunch anti-regulationists, considering the registration of women as prostitutes and sexual double standards to be the primary human rights abuse at the centre of the trafficking problem.Footnote 22

As Eileen Boris and others have argued, it was a similar story with the ILO. The interwar ILO, Boris notes, “turned into a battleground where international organizations calling for equal rights clashed with those advocating special protection”.Footnote 23 While the AC debated issuing special passports to at-risk young women, the ILO discussed barring women from night work, mining work, and other work considered especially endangering.Footnote 24 The Advisory Committee defined trafficking as a problem that affected “women and children”; and in the ILO, women’s work was also lumped in with the world of children (after 1930, it established a section explicitly dedicated to “Conditions of Employment of Women and Children”).Footnote 25 Indeed, these discourses were dependent on one another, and each contributed to the vision of women workers, especially mobile ones, as vulnerable. And yet, both organizations were working with different halves of the same puzzle: delegating to each other, respectively, questions of sexual vulnerability and labour exploitation, and therefore rendering both organizations unable to discuss the intersectional nature of the two.

The work of Jessica Pliley and Stephanie Limoncelli helps to parse some of the complicated politics of the League’s committee on trafficking. Limoncelli charts the undermining of abolitionist feminism – those campaigners who sought to abolish regulation and all “laws of exception”, as they called them, directed against “prostitutes” – and the ascendancy of prohibitionist and paternalist positions, which sought to control women in the name of protection, and which was less opposed to regulatory measures for adult prostitutes. Pliley extends this discussion, by examining the way that the actual personnel and structure of the committee was changed, reducing the number and the influence of these delegates in the committee. This was no accident, argues Pliley, and was part of a larger movement to give more power to national representatives and less to non-governmental assessors by the 1930s.Footnote 26

This certainly goes some way to explaining why women’s work was not discussed by the committee, in an atmosphere that was increasingly dedicated to finding practical and government-friendly methods of responding to trafficking. But it does not fully solve the “explanatory puzzle”, as Pliley calls it, of the League’s position, because the lack of explicit connections between discussions of women’s work and trafficking predated the erosion of feminist abolitionist power in the League. Little account was taken of the role of women’s work in relation to trafficking in the seminal “Report of the Special Bodies of Experts on the Traffic in Women and Children”, which was supported by abolitionist feminists and funded by the American Social Hygiene Council. It was commissioned by the AC in order to discover the “extent and character of the traffic”, in the face of debates about the possibly mythic nature of white slavery. After several years of investigation by under-cover researchers, the Report was published in 1927. It dwelt extensively on the way in which women were recruited and inculcated into the industry, the roles played by various pimps, traffickers, and middle men, and the relationship of regulated systems of prostitution control to the traffic in foreign women for prostitution in particular countries. In a short section on page twenty-three, the authors of the Report included a discussion of “the influence of low wages”.Footnote 27 The brevity of the section, which referred largely to the low wages of the entertainment industry rather than the systemic underpayment of women workers in modern industrial economies, was in some ways a by-product of the limited mandate of the Special Body of Experts, charged with discovering the “extent and character” of the traffic, rather than its actual causes. Evading questions of women’s exploitation within licit work was essential to staying on task.

These evasions continued, even when the matter was raised directly with the AC. In the same year that the “Report of the Special Body of Experts” was released, Mr. Maus, a German delegate, wrote a memorandum for the AC on “the effects of low wages paid to women in certain employment”, in response to its absence within the Report. The AC considered the memorandum in their sixteenth session. In an earlier draft of their report on this session, they acknowledged that “low wages constituted an important factor” in the creation of the traffic. However, in the final version of the session report, the committee had grown more equivocal, resolving that “the low wages paid to women in certain branches of employment is a factor which cannot be disregarded in considering the problem of prostitution in its relation to the traffic”.Footnote 28 [emphasis added]. As Eileen Boris argues, “Though members of the Traffic Committee bemoaned the influence of women’s low wages and subsequent poverty, they emphasized the moral over the monetary”. Meanwhile, “the ILO had only a limited interest in trafficking as a byproduct of poor labor conditions in other industries or lack of employment itself”.Footnote 29

These evasions appear particularly striking in light of the information that was available to Committee members who were considering the problem. Key studies on prostitution throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries found, repeatedly, that women and girls were motivated to sell sex because of economic factors and because of exploitative experiences in other kinds of work.Footnote 30 Yet, even campaigners who were in favour of equal rights rather than special protection were still inclined to prevaricate. Alison Neilans, the Secretary of the British feminist organization the Association for Moral and Social Hygiene, in response to Mr. Maus’ assertion that low wages paid to German women were creating a supply of trafficked women, wrote, in relation to Britain, that “[l]ow wages do not appear directly as a cause of prostitution amongst women”, although, she conceded, they “indirectly” influenced women’s prostitution. The gradual drift downward of women who turned to prostitution would, she concluded, “be greatly lessened if there was plenty of employment for women at a reasonable living wage”.Footnote 31 Neilans’ use of the term “indirectly” showed that, despite holding many progressive views on the subject, she was still caught within a late Victorian melodrama of prostitution that required the woman to be actually starving for “economic factors” to be recognized as the “direct” cause of her fall.Footnote 32

The AC was ill-prepared to investigate the matter any further, it seems. They concluded in light of Mr. Maus’ report that the matter should be referred to the ILO, whose study of “minimum wages machinery” would help to “secure the payment of an adequate wage in the lowest-paid employments”. The AC suggested that the League Secretariat should examine the issue with the ILO and report back to the Committee. The discussion did not progress from there: the issue of women’s wages and trafficked labour fell between the cracks of the two organizations.Footnote 33 Just as the issue fell between the cracks, so too did individual women. Amongst the files of the League’s Advisory Committee are many cases of distressed female migrants who were coping with starvation wages, exploitative work conditions, and abusive employers; all of whom were determined by the Secretariat to be beyond the purview of the AC on the grounds that they were not caught up within “sex trafficking”.Footnote 34

Certainly, the structure of the ILO and the AC helps to explain the way that the question of women’s work fell through the cracks in the AC’s analysis of trafficking. Another possible reason lies within the positions of the AC’s delegates themselves. As Pliley emphasizes, AC members were divided between three different approaches: firstly, those who wanted to end trafficking but supported a kind of regulation; secondly, those who wanted to take a prohibitionist approach, outlawing all forms of prostitution and (at its most extreme) regulating the movement of all women; and finally, those feminist abolitionists who sought an equal moral standard and who categorically opposed regulation. This final group was the only one that might be inclined to discuss prostitution in the context of women’s work; however, their position against regulated prostitution made this difficult. Women’s rights campaigners, as Boris notes, tended to argue that the solution to exploitation in other areas of women’s work was to bring the industry in question into the “light”, out of the home and tenement, for instance, and into the factory. But if that strategy was applied to prostitution, it suddenly became incompatible with abolitionist feminism and moral reform, which sought to eradicate any form of legalized or regulated prostitution, and did not reckon in the least the possibility that prostitutes could see themselves as workers, or self-organize.Footnote 35 While feminist abolitionists campaigned fervently to remove “laws of exception” against prostitution, which included campaigns to decriminalize streets solicitation, they campaigned with equal fervour to shut down brothels and were unequivocal about seeing prostitution as immoral and harmful.Footnote 36 “Delegates could only understand exploitation as sexual exploitation”, Boris writes of the AC, and in so doing were blind to both the way that sexual labour could (like other work) be done in good and bad conditions, and the way that women might articulate their positive engagement with that work.Footnote 37 Acknowledging that women chose prostitution because their other labour alternatives were exploitative or undesirable meant an implicit recognition that prostitution, too, was a form of women’s labour, and one that might benefit from some form of government regulation. This was something that anti-trafficking campaigners and abolitionist feminists were unprepared to do.

Trafficking and the International Entertainment Industry

There were some moments, however, which facilitated brief explorations of the entwined nature of women’s sex trafficking and women’s work within or between the two international bodies. For the most part, as Rodríguez García notes, women’s work only figured in discussions of the Advisory Committee when they discussed moral protection “by means of work” – that is, how preventing single women’s unemployment could have a salutary effect on her character and stop her drifting into prostitution.Footnote 38 However, there were also recognized instances where women needed to be protected from work. The entertainment industry was one such sector, and there are compelling reasons why both the AC and the ILO were able to speak about women’s work and trafficking in this context. The lower-class entertainment industry had long been associated with the commercial sex industry, and music hall and cabaret artistes with prostitutes.Footnote 39 In major cities around the world, theatres, dancehalls, casinos, and cabarets were known as places where women solicited sex during performances, and where “dancing girls”, “professional partners”, and barmaids were often commercially sexually available through forms of clandestine prostitution. By the early twentieth century, the global entertainment industry had established migratory circuits around the world, which corresponded to the circuits of migrant prostitution. Thus, the space – both literal and figurative – between this licit form of labour, and the illicit labour of prostitution and sex trafficking, was far smaller than with other kinds of women’s work.Footnote 40

As a result, the discussion of women’s work in the entertainment industry had always been explicitly entangled with concerns over the traffic in women and children. The 1904 International Agreement, which was drawn up after the first significant “white slavery” conference in London, recommended that governments supervise employment agencies and prevent or monitor the employment of young people abroad, with a particular focus on those agencies that supplied young female performers to the international entertainment market. Youth was the primary focus, however, and while a few governments made an effort to prevent or carefully monitor children under sixteen working as migrant entertainers under various legal instruments that were designed to protect minors, little was done to address the abuses by employers and recruiters of adult women workers in this industry.Footnote 41

The issue of women in the entertainment industry was still seen as a pressing one when the Advisory Committee on the Traffic in Women and Children met for their first session in 1921 and discussed the “Employment Abroad of Women and Girls in Theatres, Music Halls, etc.”. The British delegate, Sidney Harris, explained that women who accepted these engagements from often dubious employers, “run the risk of being put in a position in which they are induced, whether directly or indirectly, to take up a life of immorality”. In other words, the AC had a right to be concerned because of the indirect moral risk, not because of any direct exploitation or trafficking. And yet, in Harris’ analysis of a sample contract signed by a female performer travelling abroad for work, exploitation was an inherent part of the labour. Harris noted that the contract placed no limit on the number of performances, day or night. The agreement could be prolonged week by week, the performer could be sent to any location, and the woman would forfeit her return fare if she did not comply. She would be subject to unstated heavy fines should she not adhere to the rules and regulations of the agreement, which were likewise not included.Footnote 42 Harris noted that while the contract contained no “direct inducement to an immoral life […] the temptation to do so must be obvious”. What must surely have also been obvious to the AC was that the contract itself represented a codified kind of trafficking, deploying the precise methods that traffickers used to keep the women they transported for the sex industry in debt bondage to them or to the brothel keepers for whom they worked. Yet, the idea that work in the entertainment industry could itself constitute trafficked labour went unremarked.

Nonetheless, the AC considered the matter important enough for further investigation, and referred their questions about entertainment industry contracts to the ILO. In reply, Louis Varlez, in charge of emigration issues at the Organization and, for that reason, the ILO’s liaison to the AC, sought to clarify his remit, asking “whether the enquiry should cover only the question of the material and moral protection of artistes white they are touring, or whether we desire that a thorough enquiry should be undertaken on the conditions under which the contracts of artistes are concluded and how they are executed”. The second option, which would consider the exploitative nature of the contracted work itself, rather than the “indirect effects” of women performers’ drift into a life of “immorality”, was, in Varlez’ estimation, “a much more difficult question”.Footnote 43 The AC agreed, and asked Varlez to only report on the moral questions related to entertainment industry work for women. The labour abuses within the industry were therefore explicitly written out of the investigation.

In the UK, however, there was some recognition of the need to regulate the entertainment industry and its contracts because of the need to prevent inherent abuses rather than indirect immorality. In England in 1928, Labour Party MP Frank Rose, supported by two famous actresses, introduced a Bill to Parliament that came to be condescendingly known as the “Chorus Girls’ Charter”. The Bill, recognizing that “the existing law in England can be described as inadequate and partial in its application”, sought to put more restrictions on the fees and commissions that theatrical contracting agents could charge.Footnote 44 After some minor press coverage, the “Chorus Girls’ Charter” passed in its second reading.Footnote 45 But despite these successes, moral, rather than labour, protection remained the primary concern and the most significant intervention came in the form of restrictive emigration regulations. A year after the modest “Chorus Girls’ Charter” had been passed, Westminster considered amending the Children (Employment Abroad) Amendment Act, which sought to extend the measure to heavily supervise the migration of children under sixteen for work in the entertainment industry to those young people between the ages of sixteen and eighteen, the age, as one member of the House of Lords put it, when women were most susceptible to “moral dangers”.Footnote 46

Age was not the only factor that helped to distract from wider questions regarding the British state’s responsibility to uphold labour standards for adults in the entertainment industry. The racialization of what were seen as the most unscrupulous corners of this industry played an enormous role in externalizing the “evils” associated with the sector. During the review of the Children (Employment Abroad) Amendment in the House of Lords, the Lord Bishop of Southwark cited the case of “some six chorus girls who went over to Belgium, undertaking a contract to sing in music halls. When they reached Belgium, they found that their employer was a coloured man, and they were sent to a place which was described as a gambling den. After a week or so their engagement was cancelled”. Another member of the House added his own anecdote, sharing a story of chorus girls, aged seventeen, who were contracted to Egypt. “When they got to Cairo […] things were very bad, and the person in charge of them was actually on the point of taking these chorus girls to further Eastern countries to be exhibited and to dance there”.Footnote 47 At the international level, the “Report of the Special Committee of the Body of Experts” brought these racialized images of the seedy entertainment industry to international audiences, describing the South and Central American venues, marked by their ruralness, indigeneity, and racial otherness, where vulnerable “artistes and entertainers” were most likely to be led astray.Footnote 48

The focus upon the foreign, non-white, and imperial entertainment circuit functioned as a kind of double scapegoating. Firstly, because it focused on the industry that had always been implicated in immorality, rather than broadening the scope to other kinds of exploited work (such as agriculture, domestic service, or manufacturing). Secondly, by only accounting for lower-class or foreign dimensions of the entertainment industry, with its oriental licentiousness and Latin passions, the discourse shifted the gaze of law away from white, upper-class entertainments, including the high-class clubs in Western Europe where prostitution, escorts, and call girl syndicates – as well as labour exploitation – were commonplace.

Trafficking and Domestic Service

Domestic service, like the entertainment industry, had long been associated with prostitution. Not, in this case, because of its inherent licentiousness, but because the conditions of work and pay, and the sexual abuse young women were believed to often suffer at the hands of the men of their employing household, drove many young women into prostitution.Footnote 49 Many social investigations from the late nineteenth century showed that domestic servants often engaged in sexual labour casually or temporarily, and very often those engaged in more permanent sexual labour had once been domestic servants, a correlation that, in the case of the UK at least, went even beyond the normal rates of domestic service in the female population.Footnote 50 In 1943, the ILO published a study of “the moral protection of the woman worker” that it had prepared for the League’s renamed Committee on Social Questions. Here, they appeared willing to explore the connections between domestic service and prostitution, because “the risks of this particular occupation call for study [in the context of trafficking] by reason of the considerable place it occupies in the statistics of the former occupations of prostitutes”.Footnote 51 These connections should be unsurprising to historians of women’s migrant work: the patterns of migration of women who moved for domestic work and those who move for sex work have looked much the same for a long time, and prostitution and domestic service were shaped by the same economic, labour, and migration patterns as well as the same kinds of regional, social, racial, and gender inequalities.Footnote 52

Domestic service was very briefly discussed in the context of the monitoring of employment agencies during the international conference on white slavery, which led to the 1904 Convention, but, unlike the entertainment industry, it was the subject of very little cultural attention and almost no legislative interventions in the first three decades of the century. While cleaning work (or charring, as it was known in Britain) was the subject of some reformer’s attentions in the US in this period, where the hotel industry was increasingly employing large numbers of female immigrants, in Britain the discourse and economy of domestic service remained focused on the home. This silence on the question of the exploitative nature of domestic labour also helped to protect the economic and imperial interests of the British state, who had long been engaged in the active management of the migration of women for domestic service around their Empire and Commonwealth, and who had long contended with the “moral dangers” these women were thought to face. Emigration Societies sought to mitigate these moral risks for white women who left Britain, but did little to prevent (even encouraged) other kinds of labour abuses. In Blue China: Single Female Migration to Australia, Jan Gothard catalogues in detail the way that the Australian and UK government’s sponsored migration programmes for female domestic servants in the nineteenth century, frequently defrauded and indebted women who migrated into service. As newer work by Victoria Haskins, Claire Lowrie and others demonstrates, the line between trafficking and domestic labour within empires became even more blurred in the case of the often forced, indentured, or coerced servitude of non-white and indigenous women.Footnote 53

By the 1920s, Britain faced a serious domestic labour supply crisis at home. While Britain began to close its doors to European migration after World War I, the Ministry of Labour suggested putting domestic service on a list of shortage occupations for which a permit could be granted.Footnote 54 This labour was, however, difficult to monitor and manage. As Cyril Joad, a socialist who worked as a civil servant at the Ministry, noted, the (often desperate) European domestic servants would accept “rather low wages”.Footnote 55 By the 1930s, Britain’s “servant crisis”, as it was known, had grown more acute in the face of economic depression and political upheaval in Europe. As historians Caestecker and Moore note, Britain became increasingly reliant on European foreign domestics, fleeing a harsh economic and political climate at home, to fill vacancies. The work permits they were issued disallowed the holder from seeking any other form of employment. “In this way”, argue Caestecker and Moore, “they were chained to domestic service and an unconditional leave to remain was postponed indefinitely”.Footnote 56 In an era when the contracted worker was supposed to be “free”, female migrant labour in the domestic service industry remained highly coercive. Indeed, this period, which witnessed the sharp rise in the migration of women to work in care and service industries in Britain, helped to lay the groundwork for what has today grown to be an army of foreign domestic labourers who work under exploitative conditions. Some of these women are constrained by their illicit migration status, while others are constrained by the coercive terms of their work visas, which bar them from seeking other employment and threaten them with deportation should they lose their jobs.Footnote 57

In the early twentieth century, organizations dedicated to anti-trafficking campaigns and the moral welfare of migrant women could not help but pay careful attention to the trafficking-like nature of this kind of migrant domestic work. One of the most important organizations in this regard was, somewhat ironically, the National Vigilance Association (NVA), which had been amongst the most fervent in defining “white slavery” as a specific problem of international crime control and protection.Footnote 58 They were certainly never on the vanguard of radical campaigns that emphasized the connections between prostitution and exploitative work. Yet, through their work monitoring rail stations and ports to watch for cases of “white slavery”, the NVA was also the organization most frequently exposed to the permeable borders between prostitution, trafficking, and labour exploitation on the ground. Patrolling the train stations and ports of Britain in the 1920s and 1930s meant dealing with cases where exploitation and trafficking was occurring within licit, non-sexual occupations. NVA files are filled with hundreds of cases of European domestic workers who, upon arrival in the London, were left without contacts, were boarded in squalor, were underpaid or unpaid, were prevented from leaving their positions, or were terminated without reason. As a result, the NVA found itself shifting its efforts from watching suspected brothels for cases of “white slavery” to keeping lengthy dossiers on exploitative domestic service employment agencies and employers.Footnote 59

In his sensationalized warning to “girls going to London to seek work”, NVA secretary, journalist, and former police officer FR Sempkins noted that “[p]eriodically there is an outcry about girls being lured to London and trapped by White Slavers. Those of us who deal with facts must deplore all exaggeration. It discredits the truth, and diverts attention from a situation which is sufficiently grave to need no colouring”. Domestic service, he told the readers of Tit Bits, a popular weekly paper, was as much a source of “white slavery” as was prostitution.Footnote 60 Later pamphlets produced by the NVA (renamed the British Vigilance Association and the National Committee for the Suppression of Traffic in Persons) reflected this shift from looking at trafficking as connected only to prostitution to seeing it as entwined with women’s migrant labour. The pamphlet “Coming to Work in Britain?”, which alerted female migrant workers to the danger of being trafficked and encouraged them to look for the armbands of NVA volunteers upon their arrival, depicts work in the entertainment and service industries, highlighting especially work by women of colour, and by women coming to London from rural areas of the UK.

However, as in the case of the entertainment industry, the keenest abuses within the domestic service sector were made out to be the fault of racialized foreigners. While the NVA did keep files on English, Irish and other employers and agencies, it was the Jewish employment agencies and East End Jewish employers of servants who received the bulk of their concern and attention. Sempkins elaborated: mistresses were “often slavedrivers, uncouth, un-English, totally unfitted to have servants. Before the distress [the economic crisis of the early 1930s] they could not possibly have obtained servants”. He sketched an image of London domestic service as a new form of the Jewish white slave trade, noting (incorrectly) that “ninety percent of the girls from the northeast [of England] go to Jewish families”.Footnote 61 This not only capitalized on pervasive sentiments of xenophobia and anti-Semitism, but also provided a way in which to launch a critique of domestic service as trafficking without implicating themselves, and their own servant-keeping and consumption practices, at the same time.

While discourses surrounding migrant entertainment work as a cause of trafficking were primarily concerned with age, and while legislation focused on protecting young women under the age of sixteen or eighteen, a parallel conversation was largely absent in the case of domestic service within Britain. This is because the youth of servant girls had been naturalized in the West for centuries. In fact, the ideal “slavey” – or maid of all work – would be young: more able to cope with the working hours and physical demands of the labour, less likely to be insubordinate to their masters and mistresses, and less likely to have any other personal caring demands made on their time. Within the British Empire, however, age and domestic service took on new meanings in the case of the British-led campaigns around Mui Tsai: the cultural practice, known throughout South East Asia, of families selling their young daughters to wealthier households as indentured servants. It was another case where racialization – this time ideas about Chinese backwardness and uncivility – was deployed to prevent discussions of a specific kind of women’s exploited work from becoming a broader recognition of the systemic inequalities of the global – and Western – economic system.Footnote 62

The economic and political conditions of Europe in the 1930s likewise led the ILO to focus more carefully on women’s domestic service and migration in the international arena. In 1933, the ILO adopted a convention that supported the complete abolition of fee-charging employment agencies, and the supervision of all employment agencies, especially those who placed workers in foreign countries. One of the reasons they offered for supporting this rather radical convention was the “abuses which domestic servants suffer at the hands of unscrupulous agents”.Footnote 63 While the convention was ratified by only a handful of states, and was largely a dead letter, it was nonetheless clear that the ILO was starting to speak formally about the connections between trafficking and women’s domestic work.

The next major contribution to this discussion came in 1943, in a chapter that the ILO had prepared for the volume “The Prevention of Prostitution”, for the League of Nations Advisory Committee on Social Questions (into which, arguably to its detriment, the AC on the Traffic in Women and Children had been subsumed). The chapter, entitled “The Moral Protection of Young Women Workers”, appeared to be a culmination of many of the questions which the Advisory Committee had passed onto the ILO in the 1920s and 1930s and whose publication had ultimately be delayed by World War II. “A girl who goes to work”, the ILO’s chapter began, “may clearly be faced with other risks than those inherent in her employment”.Footnote 64 The study would therefore be concerned with “the risk of demoralization connected with the placing of young workers, those arising at the work-place itself, and lastly those to which they are exposed outside their work”: not, therefore, though it remained unsaid, with the nature of the work itself. The chapter suggested typical measures of protection, such as the barring of underage employment in potentially demoralizing environments such as hotels, bars, and theatres. It continued at some length regarding provisions for young, single, migrant women workers after working hours, suggesting that states and charities should ensure more formal provision and supervision of leisure spaces.Footnote 65

However, it proved very difficult for the ILO to maintain the division between trafficking for prostitution and other forms of exploitative migrant labour and their chief recommendation – the reiteration of the 1933 Convention that called for the abolishment of all fee-charging employment agencies, and restrictions on the numbers of foreign workers able to be recruited – applied to all workers. This was a direct response to the problem of migrant domestic workers. During their investigations, the ILO found that in most countries, domestic servants represented two thirds or more of the total workers placed by fee-charging agencies, the vast majority of these, of course, being women.

Within this chapter, the ILO recognized domestic service as an occupation that could involve significant “moral danger”, but also one whose labour structure was fundamentally conducive to exploitation. They argued, for instance, that the reasons why age regulations could not realistically be imposed on the employment of domestic servants was because making sure the age was high enough “to enable girls to enter the occupation only when in full possession of their individual powers of self-defense” would be an impediment to finding women to fill the positions, in a sector where there was already a critical labour shortage. “There is no hope”, the ILO wrote pessimistically, “of establishing in the near future an age-limit which will really protect young domestic servants against this special risk”.Footnote 66

The ILO also analysed the reasons why state and international approaches to trafficking had largely taken the form of protectionist legislation and crime control. “The negative method of protection’, they wrote, such as banning children and women from night work, from work in foreign countries, or from work in certain occupations, was successful because was simple for states to apply and administer. What the ILO authors called “positive methods of protection” required more effort: these included child welfare boards, government services to help migrants review contracts, and minimum wage and labour standard enforcement.Footnote 67 This cynical passage, which essentially said that the criminalization of prostitution and protective legislation was enacted because it was easier than the implementation of labour standards, was extremely insightful, and represented a passing but nonetheless powerful critique of the legal machinery that had grown up in the name of trafficking.

At the national level, these elusive “positive methods of protection” were largely absent. Only five countries agreed to enforce the ILO’s recommendation to abolish private, fee-charging agencies, and Britain was not one of them. It continued to grant work permits to domestic servants, without regard to the character or repute of the agencies that had recruited them. No state-sponsored effort existed to help young women considering employment abroad, and even the protective measures directed at working migrant women were left to a loose network of philanthropic and religious organizations: the only partially government funded home for trafficking victims was closed in the mid-1930s, and women in need of shelter were redistributed around the religious philanthropic sector. Trafficking itself was explicitly conceived of by the British state as a subject of crime control, and all matters related to the movement of “foreign prostitutes” – exploited or not – were relegated to the police, magistrates, and immigration officials, whose main jobs were to suggest, sign, and approve deportation orders.Footnote 68

Entangling Trafficking and Migrant Female Labour

For historians, re-entangling trafficking and migrant prostitution with migrant women’s labour can help us to rethink both the way that discourses about trafficking and prostitution functioned and the way that states responded to the perceived problems of the sexual and labour exploitation of migrant women. In particular, thinking about migrant domestic labour and migrant sexual labour as intimately historically related and discursively entangled has the power to disrupt not only the invariable reduction of trafficking to prostitution, but also the understanding of trafficking as something done by organized criminals as opposed to the state.

The discourse of sex trafficking was messily constructed to create a false dichotomy between the legitimate state’s control of migration and illegitimate organized crime’s control of migration, whereas, in reality, both acted to exploit working class women’s fluid, mobile, and cheap labour and achieved this aim in similar ways – threats of repatriation, defrauding, imprisonment, the confiscation of identity documents, and control over the specific labour that the person who was trafficked, smuggled, or sponsored was required to perform. The discursive separation of “trafficking” from “migrant labour” also enabled states to respond to the supposedly specific problem of “white slavery” while avoiding committing themselves to any complex or costly interventions that would improve global labour standards.Footnote 69 Trafficking, especially sex trafficking, was an economic, legislative, and discursive space in which concerns about exploitation, which, in reality, affected all labour, could be quarantined and managed. This was largely done, as a growing number of social scientists and historians are discovering, through escalating systems of national and international crime control.

One way to explain the deafening silence on sex trafficking in discussions of women’s work in the ILO, the League of Nations, amongst key non-governmental organizations, and in British national policy and laws would be to say that it was owing to a refusal to acknowledge that prostitution could be work. This refusal to acknowledge prostitution as work is of course a key element in much feminist and political thinking on prostitution on the international stage today. This is, however, an overly simplistic assessment of the way in which discourses around trafficking and women’s migrant labour developed and functioned. Firstly, the idea that prostitution was a kind of labour, or at least a money-making, alternative to women’s non-sexual exploited labour was a widely voiced, mainstream socialist position as early as the late nineteenth century and it continues to this day, even in (albeit marginalized) discussions within the UN and ILO.Footnote 70

Secondly, these silences were not just about denying that prostitution was work: they were as much about constructing a discourse that denied the possibility, widely recognized in earlier periods, that state-approved work could be exploitative. Ideas about “free” and “unfree” labour was recodified in the twentieth century through the discourse of trafficking and – in the twenty-first century – “modern slavery”. As Julia O’Connell Davidson notes, the figure of the “slave” was used by the post-abolition era to “celebrate the rights and freedoms bestowed on the abstract, juridical subjects of capitalist democracies”.Footnote 71 Trafficking in this context enabled a discussion of exploitation that did not extend to ordinary, supposedly licit, work. Because discourses of trafficking were heavily gendered, they functioned as doubly obfuscating, in that they concealed not only the exploitative nature of women’s work, but also denied the very existence of women’s work as a fundamental part of global labour systems.

Thirdly, while sex trafficking helped to semantically and legally separate prostitution from work, and make it a specific kind of issue to be dealt with through crime control and specialized migration regimes (i.e. the deportation of foreign prostitutes), these separations were actually far from successful. The legal and cultural understandings of trafficking as distinct did little to change the fact that work – including sex work – remained a complicated category on a spectrum of freedom and unfreedom, of agency and exploitation. Elizabeth Berstein convincingly argues that present-day abolitionist feminists have “effectively neutralized domains of political struggle around questions of labour, migration and sexual freedom via the tropes of prostitution as gender violence and sexual slavery”.Footnote 72 However, this is a much older story, and present day campaigners have inherited at least as much as they have created: as this article has helped to show, the depoliticization of women’s labour exploitation through the discourses of sex trafficking was present at the very inception of the campaigns against “white slavery”. It has proved an enduring legacy.

But this article has also explored some examples of places where the conceptual and practical borders between sex trafficking and women’s licit labour migration became porous and problematic in the first half of the twentieth century. Organizations dedicated to tackling trafficking, and those dedicated to protecting migrant women workers, were rarely able to neatly articulate the divisions between these inseparable phenomena. As Peck argues in his examination of the American anti-slavery bureaucrat Marcus Braun, the “traffickers in the ideology of trafficking” had great difficulty controlling the message of white slavery.Footnote 73 The development of anti-trafficking policy at the national level especially was not just a story of a deliberate abolitionist campaign establishing the terms through which sex trafficking needed to be understood, but rather a complicated process that owed as much to international bureaucracy, the limitations of the law, and the cynical pragmatism of national policymakers as it did to ideology. Arguments were framed in terms of moral protection, but underneath these discourses lay acknowledged or tacitly recognized realities of exploitation outside of sexual labour, and within licit and state-sponsored labour practices, especially in the entertainment and service industries. Those who helped form the dominant discourse and legal regime surrounding trafficking were forced to steer through dangerous waters – where, on the one hand, lay the moral and political rocks that they would hit if they attempted to explicitly consider prostitution as part of a global labour system, and, on the other, the hard place of trying to explain prostitution and trafficking without reference to this broader system of work and inequality.

Despite attempts to resist using a trafficking or exploitation framework to analyse so-called normative women’s domestic and entertainment labour, it was nonetheless clear that, however much organizations and policymakers attempted to keep the issues separate, the borders between prostitution and women’s licit labour had been breached. They would grow ever more porous as the century progressed, even as definitions of trafficking, prostitution, and work became more rigid. While legal interventions and international declarations failed to recognize what Adam McKeown calls the “intermediary conditions” of freedom and unfreedom, these fluid conditions were navigated by migrant workers themselves in all their complexity. Throughout the twentieth century as well as today, the entangled experiences of women’s sexual labour and licit labour, of their sexual exploitation and of their exploitation as workers, belied any attempt to codify the categories of working women’s migration.