Receiving a diagnosis of dementia is an important step for people with dementia because it facilitates access to interventions, and potential support from health and social services and third-sector organizations (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Tang and Taylor2015). Receiving a diagnosis may be an emotionally charged experience, representing a transition in identity for people with dementia and their carers requiring an emotional readjustment and reappraisal of their future (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson2011). The proportion of those developing symptoms of dementia who receive a diagnosis has increased in the UK (Abhayaratne et al., Reference Abhayaratne, Blanchard, Cartwright and Greally2019) and internationally (World Health Organization, 2020), partly in response to policy changes (Department of Health, 2015), and due to greater awareness and acceptance of dementia. A recent systematic review (van den Dungen et al., Reference van den Dungen2014) using a pooled average based on 9,065 respondents from 23 studies demonstrated that approximately 85% of people with cognitive impairment would wish to be told a diagnosis if one were made. Knowledge of prognosis and illness trajectories enables people to plan and ensure their affairs are in order or undertake lifestyle changes (Woods et al., Reference Woods2019). Typically, in developed countries, diagnosis disclosure occurs in secondary care settings, conducted by professionals such as psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, or specialist nurses. However, some diagnosis disclosures occur in primary care, delivered by a primary care physician (PCP). The time from developing awareness of cognitive changes to receiving a diagnosis varies across individuals, but can be a lengthy process; a delay of 3 years is not uncommon (Chrisp et al., Reference Chrisp, Thomas, Goddard and Owens2011). The communication and delivery of the diagnosis require careful management to account for a variety of reactions, needs, and levels of understanding from both the person with dementia and carers accompanying them to the disclosure meeting (Bunn et al., Reference Bunn2012).

There are differences between healthcare professionals’ (HCPs) perceptions of best practice when disclosing a diagnosis of dementia and the perceptions of people with dementia or carers, which raises ethical dilemmas about how to respect these different needs (Dooley et al., Reference Dooley, Bailey and Mccabe2015). An earlier literature review (Lecouturier et al., Reference Lecouturier2008) identified a list of best practice behaviors and combined this with a qualitative exploration and consensus approach to identify eight categories of best practice for disclosure. These categories comprised preparing for disclosure, integrating family members, exploring the patient’s perspectives, disclosing the diagnosis, responding to the patient’s reactions, focusing on quality of life (QoL) and well-being, planning for the future, and communicating effectively. While comprehensive, this review is now over 10 years old and the authors did not critically appraise the included research. Another review (Werner et al., Reference Werner, Karnieli-Miller and Eidelman2013) covering a similar topic and time frame addressed a broad range of topics related to dementia diagnosis disclosure, but without a specific focus on which practices are typical and how they might be perceived. Given the recent policy initiatives around early diagnosis and changes in societal awareness of dementia over the last decade (Department of Health, 2015), an updated review of the evidence regarding disclosure from the perspectives of people with dementia, carers, and HCPs is required.

Objectives

This review aimed to explore the experiences of giving or receiving a diagnosis of dementia. It identified common disclosure practices, challenges associated with disclosing the diagnosis, and needs of different individuals involved in the disclosure. It extended earlier work by including a systematic search strategy and a critical appraisal of the results using an established quality assessment tool and went beyond describing the range of possible practices and behavior to identify what is reported as typically occurring in practice and how this is perceived.

Methods

Search strategy

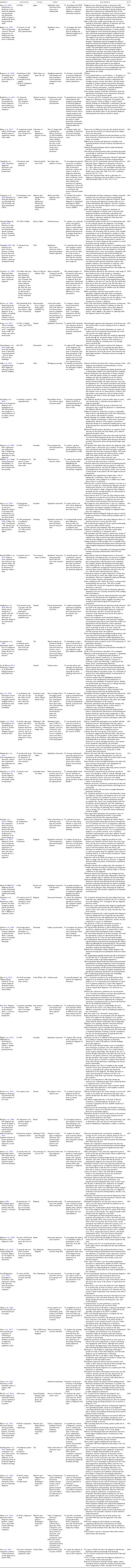

A search of the PubMed, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases was conducted on 31October 2018; updated on 7 February 2020. Reference sections of included papers were hand-searched to identify further publications. The terms “dementia” AND “diagnosi*” were used to search titles and abstracts. A second search was conducted which combined these with the terms “disclosure” OR “best practice,” used to search in all fields. The study flowchart is shown in Figure 1. Due to the large number of studies conducted on this topic, the search was restricted to the last 10 years (2008 onward).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of included studies.

Study selection

Studies were included if they were written in English and provided information on delivering or receiving a diagnosis of dementia. All study types were eligible except for papers that only included a review of previous literature. Studies from the perspectives of HCPs, patients, and carers were all considered. The two primary reviewers (JY and MS) screened the titles, excluding papers that were not relevant, and then reviewed the abstracts. Full texts were retrieved if the title and abstract suggested that an aspect of delivering or receiving a diagnosis of dementia was explored. JY and MS conducted this task jointly, resolving differences in judgment through discussion and agreement.

Data collection and synthesis

Data were extracted using a table developed by JY and MS to capture the study details (Table 1). Initially, JY and MS extracted the data together to ensure consistency, before continuing to extract data independently and amalgamating tables once complete. As data were extracted, a number of similar ideas and issues were identified in the findings. These were collated in a separate document and added to by JY and MS until data extraction was complete. Similar findings were grouped to form thematic categories. These themes were refined and amalgamated where possible through discussion and during the writing of the narrative by the whole research team. Themes were reported in a narrative format.

Table 1. Main findings and study details of included studies

AD: Alzheimer’s disease, GP: general practitioner, MAS: memory assessment service, OAMHTs: Older Adult Mental Health Teams, PwD: people with dementia

Quality review

Methodological quality was assessed by JY and MS using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklists (Aromataris and Munn, Reference Aromataris and Munn2017). The corresponding checklists for each study design were used. A rating of methodological quality that was comparable across different designs was made by calculating the number of items endorsed on each checklist for each paper and converting this into a percentage. Ten percent of the papers were sampled using a random number generator and assessed for quality by a third reviewer (AH). Reviewer scores were compared for consistency using a paired samples t-test. No significant differences were found (t(4) = 2.33, p = .080), suggesting a robust quality assessment.

Results

Fifty-two studies were included. Main findings are summarized in Table 1. Findings are categorized under the following themes: content of the diagnosis disclosure; emotional impact; communication of the diagnosis; people involved; attitudes toward diagnosis disclosure; use of diagnostic tests and assessments; truth telling and deception; timeliness; and training and skills.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment scores are shown in Table 1. Detailed assessments can be obtained on request. The scores represent the percentage of items on each study design-specific checklist endorsed, and higher percentages reflect higher quality. Scores ranged from 60% to 100%, and of the 52 studies, 13 scored 100%, seven scored 90–100%, 14 scored 80–90%, 12 scored 70-80%, and six scored 60–70%. Studies scoring lower tended to have qualitative designs. The most frequent quality issues included a failure to specify the underpinning philosophy of the research approach, so the congruence between the philosophical perspective and the research methodology was unknown, and a lack of reflexivity to locate the researcher culturally and theoretically, acknowledging the impact of the researcher on the research and vice versa. Studies scoring higher tended to utilize survey designs, consensus methods, and observations.

Study design types

This review included 1 case report, 20 cross-sectional studies yielding quantitative data, 5 studies that were opinion pieces, commentaries, or utilized consensus methodologies with experts, 24 qualitative studies, 2 quasi-experimental studies, and 1 randomized controlled trial.

Participant characteristics

Participants were HCPs, people with dementia, carers, and people who had attended memory assessment services but not received a diagnosis of dementia at the time of participation. Sixteen studies included only the perspectives of HCPs, four studies included only the perspectives of people with dementia, one study included the perspectives of people without a diagnosis of dementia, and seven studies included only the perspectives of carers. Sample sizes ranged from 2 to 1409. The term “carer” was used in most studies to refer to the individual accompanying the person receiving the diagnosis to the disclosure meeting. Other terms including “relative” and “companion” were also used (Table 1). For brevity, the term “carer” is used in this review.

Setting

Studies were conducted in clinic and community settings, in the UK (Eccles et al., Reference Eccles2009; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, De Boos and Moghaddam2018; Hillman, Reference Hillman2017; Innes et al., Reference Innes, Szymczynska and Stark2014; Manthorpe et al., Reference Manthorpe2013; Milby et al., Reference Milby, Murphy and Winthrop2017; Page et al., Reference Page, Davies-Abbott, Ingley and Bee2015; Peel, Reference Peel2015; Samsi et al., Reference Samsi2014; Stokes et al., Reference Stokes, Combes and Stokes2014; Vince et al., Reference Vince, Clarke and Wolverson2017; Lecouturier et al., Reference Lecouturier2008; Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Dooley and Mccabe2019; McCabe et al., Reference Mccabe, Pavlickova, Xanthopoulou, Bass, Livingston and Dooley2019; Xanthopoulou et al., Reference Xanthopoulou, Dooley, Meo, Bass and Mccabe2019), USA (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Johnson, Liebmann, Bothwell, Morris and Vidoni2017; Lim et al., Reference Lim, Maruff, Getter and Snyder2016; Lingler et al., Reference Lingler2016; Connell et al., Reference Connell, Roberts, Mclaughlin and Carpenter2009; Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter2008; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Stocking, Hougham, Whitehouse, Danner and Sachs2008; Bradford et al., Reference Bradford2011; Grill et al., Reference Grill2017; Grossberg et al., Reference Grossberg, Christensen, Griffith, Kerwin, Hunt and Hall2010; Sakai and Carpenter, Reference Sakai and Carpenter2011; Wynn and Carpenter, Reference Wynn and Carpenter2017; Zaleta and Carpenter, Reference Zaleta and Carpenter2010; Zaleta et al., Reference Zaleta2012; Champlin, Reference Champlin2020), China (Zou et al., Reference Zou2017), the Netherlands (van Wijngaarden et al., Reference van Wijngaarden, van der Wedden, Henning, Komen and The2018), Brazil (Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Raicher, Takahashi, Caramelli and Nitrini2008; Raicher et al., Reference Raicher2008), Belgium (Segers, Reference Segers2009; Mormont et al., Reference Mormont, de Fays and Jamart2012), Australia (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips2012; Mastwyk et al., Reference Mastwyk, Ames, Ellis, Chiu and Dow2014; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Hughes, Routley and Robinson2008), Denmark (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen2018), Ireland (Moore and Cahill, Reference Moore and Cahill2013; Foley et al., Reference Foley, Boyle, Jennings and Smithson2017), Canada (Lee and Weston, Reference Lee and Weston2011), Finland (Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008), Israel (Karnieli-Miller et al., Reference Karnieli-Miller2012), Germany (Kaduszkiewicz et al., Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Bachmann and Van den Bussche2008), Switzerland (Giezendanner et al., Reference Giezendanner2018), Japan (Abe et al., Reference Abe, Tsunawaki, Matsuda, Cigolle, Fetters and Inoue2019), and Malta (Caruana-Pulpan and Scerri, Reference Caruana-Pulpan and Scerri2014). Three studies used a pan-European design, involving several countries contributing to data collection (Porteri et al., Reference Porteri, Galluzzi, Geroldi and Frisoni2010; Visser et al., Reference Visser, Wolf, Frisoni and Gertz2012; Woods et al., Reference Woods2019) and one study was international (Villars et al., Reference Villars2010). The majority of studies were conducted in the UK (12 studies) and the USA (13 studies).

Themes

Content of the diagnosis disclosure

In a survey of specialist physicians in Denmark, most respondents reported that they always or often provided information on etiology, progression, and causes of symptoms, and they tailored the information provided depending on the degree of cognitive impairment, specific type of dementia, and level of emotional distress (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen2018). People with dementia and carers in other studies reported receiving only basic information and felt they lacked information (Samsi et al., Reference Samsi2014), or that nothing was explained (Innes et al., Reference Innes, Szymczynska and Stark2014). Messages conveyed should be positive and hopeful, while still being realistic (Vince et al., Reference Vince, Clarke and Wolverson2017; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips2012; Lee and Weston, Reference Lee and Weston2011; Lecouturier et al., Reference Lecouturier2008; Grossberg et al., Reference Grossberg, Christensen, Griffith, Kerwin, Hunt and Hall2010). People with dementia and carers indicated that they wanted to know more about the future and prognosis (Lecouturier et al., Reference Lecouturier2008; Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008; Grossberg et al., Reference Grossberg, Christensen, Griffith, Kerwin, Hunt and Hall2010; Lee and Weston, Reference Lee and Weston2011), sources of support, and local community health and social services (Foley et al., Reference Foley, Boyle, Jennings and Smithson2017; Innes et al., Reference Innes, Szymczynska and Stark2014). The diagnosis disclosure should include information regarding well-being, such as how people with dementia can continue with life as much as possible, maintain their sense of self, and accept their identity as a person with dementia (Vince et al., Reference Vince, Clarke and Wolverson2017).

Carers in two studies reported being unsure what to ask in the disclosure meeting (Manthorpe et al., Reference Manthorpe2013,;Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008) and felt that approaching diagnosis in stages might be preferable to enable people with dementia and carers to absorb and process the information (Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008; Lecouturier et al., Reference Lecouturier2008). However, in one study, 55% of respondents reported preferring to receive the whole disclosure up-front (Mastwyk et al., Reference Mastwyk, Ames, Ellis, Chiu and Dow2014).

The diagnostic process should be structured to ascertain the beliefs, expectations, and potential misconceptions that people with dementia or carers might have. This might include determining what people with dementia already know about dementia (Lee and Weston, Reference Lee and Weston2011) and identifying patient-centered informational needs (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, De Boos and Moghaddam2018) and may take place in pre-diagnostic counseling ahead of disclosure meetings (Lecouturier et al., Reference Lecouturier2008).

Emotional impact

Eighteen studies explored the emotional impact of receiving a diagnosis of dementia. Studies reporting on the emotional impact of the diagnosis on people with dementia suggested they had experienced negative emotions (Zou et al., Reference Zou2017; McCabe et al., Reference Mccabe, Pavlickova, Xanthopoulou, Bass, Livingston and Dooley2019), including feelings of depression (Segers, Reference Segers2009; Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008), anxiety or nervousness (Segers, Reference Segers2009; Mormont et al., Reference Mormont, de Fays and Jamart2012; Lim et al., Reference Lim, Maruff, Getter and Snyder2016), shock (Samsi et al., Reference Samsi2014; Milby et al., Reference Milby, Murphy and Winthrop2017; Innes et al., Reference Innes, Szymczynska and Stark2014), loss (Samsi et al., Reference Samsi2014), grief (Samsi et al., Reference Samsi2014; Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008), dejection (Samsi et al., Reference Samsi2014), sadness (Mormont et al., Reference Mormont, de Fays and Jamart2012), fear (Milby et al., Reference Milby, Murphy and Winthrop2017; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips2012), and shame (Kaduszkiewicz et al., Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Bachmann and Van den Bussche2008). One study reported that the diagnosis disclosure also brought satisfaction at receiving an explanation (Mormont et al., Reference Mormont, de Fays and Jamart2012). Three studies reported that some people with dementia were either indifferent upon receiving the diagnosis (Segers, Reference Segers2009), had not experienced significant distress (Zaleta et al., Reference Zaleta2012), or showed initial anxiety that was not sustained over time (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Johnson, Liebmann, Bothwell, Morris and Vidoni2017). A further study reported that anxiety decreased in people with dementia after receiving their diagnosis, particularly for those with high anxiety prior to the diagnosis (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter2008). Studies on the perspectives of HCPs suggested that some people with dementia deny or minimize the diagnosis (Segers, Reference Segers2009; Kaduszkiewicz et al., Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Bachmann and Van den Bussche2008). Studies exploring the perspectives of carers or family members found they reported feeling anxious (Segers, Reference Segers2009; Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008), uncertain (van Wijngaarden et al., Reference van Wijngaarden, van der Wedden, Henning, Komen and The2018; Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008), hopeless (Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008), lonely (Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008), that their hope and trust in the future was taken away (van Wijngaarden et al., Reference van Wijngaarden, van der Wedden, Henning, Komen and The2018), and anxiety and uncertainty due to not knowing where to get help or what to do next (Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008). One study found that carers reported a sense of relief and validation that their observations about something being wrong were correct, which in turn led to a sense of acceptance. However, this study also found that carers felt sad, terrified, overwhelmed, and worried (Champlin, Reference Champlin2020). HCPs reported feeling a need to manage their own emotional journey (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, De Boos and Moghaddam2018). General practitioner (GPs) reported a sense of trepidation regarding the disclosure (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips2012) and were hesitant and expressed worry regarding the negative psychological impact upon people with dementia of the diagnosis disclosure due to stigma (Abe et al., Reference Abe, Tsunawaki, Matsuda, Cigolle, Fetters and Inoue2019).

Communication of the diagnosis

Communication was explored in 21 studies. There were conflicting findings regarding using explicit terms such as “dementia” or specific labels like “Alzheimer’s disease” when communicating the diagnosis to people with dementia and carers. Five studies reported that such terminology should be used (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, De Boos and Moghaddam2018; Grossberg et al., Reference Grossberg, Christensen, Griffith, Kerwin, Hunt and Hall2010) and was commonly used (Raicher et al., Reference Raicher2008; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen2018; Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Dooley and Mccabe2019), but eight reported that HCPs tended not to use these terms (Zou et al., Reference Zou2017; Zaleta et al., Reference Zaleta2012; Segers, Reference Segers2009; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips2012; Moore and Cahill, Reference Moore and Cahill2013; Milby et al., Reference Milby, Murphy and Winthrop2017; Kaduszkiewicz et al., Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Bachmann and Van den Bussche2008; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Hughes, Routley and Robinson2008). Reasons for not using specific terminology were that ambiguous language may be preferable when HCPs themselves are uncertain of the diagnosis (Zaleta et al., Reference Zaleta2012; Milby et al., Reference Milby, Murphy and Winthrop2017), and unambiguous terms were not always helpful in facilitating the person with dementia’s understanding (Peel, Reference Peel2015). Other reasons included minimizing distress (Milby et al., Reference Milby, Murphy and Winthrop2017; Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Dooley and Mccabe2019), avoiding negative connotations of the word “dementia” (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips2012), and avoiding pathologizing the condition (Abe et al., Reference Abe, Tsunawaki, Matsuda, Cigolle, Fetters and Inoue2019). Cultural differences were highlighted, suggesting that colloquial terms were used because they were more familiar to the local community (Abe et al., Reference Abe, Tsunawaki, Matsuda, Cigolle, Fetters and Inoue2019).

Considering communication patterns in consultations, one study found that HCPs tended to dominate the disclosure meeting by talking on average for 83% of the time. Emphasis shifted from the person with dementia to the carer even when the person with dementia was in the mild stages of the condition and still able to speak and contribute information (Wynn and Carpenter, Reference Wynn and Carpenter2017). While patient-centered communication was noted in one study, findings suggested that aspects of communication such as emotional rapport building were infrequent (Zaleta and Carpenter, Reference Zaleta and Carpenter2010). Three studies indicated that written information should accompany disclosure meetings (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen2018; Mastwyk et al., Reference Mastwyk, Ames, Ellis, Chiu and Dow2014; Grossberg et al., Reference Grossberg, Christensen, Griffith, Kerwin, Hunt and Hall2010).

People involved

There were mixed findings regarding who should disclose the diagnosis. One study suggested specialists should always take this role (Villars et al., Reference Villars2010) with another suggesting that specialists could occupy a position of blame in contrast to the GP, who could provide support to patients (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips2012). However, this study also reported that GPs should take on the role of disclosure when a well-developed patient–doctor relationship existed because they would be known to the patient compared to a specialist. A Swiss survey reported that 75% of GPs disclosed the diagnosis themselves (Giezendanner et al., Reference Giezendanner2018). Other professionals have roles in disclosure, suggesting that discussing well-being should be undertaken by a multidisciplinary team (Vince et al., Reference Vince, Clarke and Wolverson2017), although psychiatrists wanted more time to discuss well-being during the disclosure to avoid being seen as someone who only diagnoses conditions and prescribes medication (Vince et al., Reference Vince, Clarke and Wolverson2017).

The majority of papers agreed it was beneficial for carers to accompany the person with dementia to disclosure meetings (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips2012; Page et al., Reference Page, Davies-Abbott, Ingley and Bee2015; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen2018; Grossberg et al., Reference Grossberg, Christensen, Griffith, Kerwin, Hunt and Hall2010; Bradford et al., Reference Bradford2011; Lingler et al., Reference Lingler2016; Abe et al., Reference Abe, Tsunawaki, Matsuda, Cigolle, Fetters and Inoue2019; Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Dooley and Mccabe2019; Giezendanner et al., Reference Giezendanner2018). Family members often wanted more information and could receive education to help them cope in the future (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips2012; Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Dooley and Mccabe2019). Carers represent a reassuring presence for the HCP (Page et al., Reference Page, Davies-Abbott, Ingley and Bee2015), can help them communicate the diagnosis more effectively to the person with dementia (Grossberg et al., Reference Grossberg, Christensen, Griffith, Kerwin, Hunt and Hall2010), and help to recall details of the diagnosis (Bradford et al., Reference Bradford2011; Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Dooley and Mccabe2019). One study found that, within its sample, people with MCI showed a lack of health literacy, suggesting carers were necessary to help process and understand the information provided (Lingler et al., Reference Lingler2016). Further, one study suggested that carers are usually most troubled by symptoms of dementia, and using disclosure meetings to reassure them is important (Abe et al., Reference Abe, Tsunawaki, Matsuda, Cigolle, Fetters and Inoue2019). HCPs in one study suggested that fuller details of the diagnosis were disclosed to carers rather than people with dementia (Kaduszkiewicz et al., Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Bachmann and Van den Bussche2008). A key point here is the lack of people with dementia as participants in the included studies, which limits the ability to draw conclusions regarding their preferences for their own and others’ involvement.

Attitudes toward diagnosis disclosure

Studies investigating HCPs’ attitudes toward disclosing the diagnosis found it can be perceived as draining (Milby et al., Reference Milby, Murphy and Winthrop2017); they might feel like the “grim reaper” when delivering bad news (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, De Boos and Moghaddam2018) or worry that the process could ruin doctor–patient relationships (Kaduszkiewicz et al., Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Bachmann and Van den Bussche2008). Some psychiatrists may hold a medically rooted nihilistic and reductionist attitude due to a sense of hopelessness around potential interventions for people with dementia and a lack of appropriate services to support well-being (Vince et al., Reference Vince, Clarke and Wolverson2017). Geriatricians who did not provide information on progression and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease to the person with dementia reported this was because the person with dementia did not ask, or the HCP was either fearful of a depressive reaction or felt the knowledge was of no use (Segers, Reference Segers2009).

Carers typically approached diagnosis disclosure as a useful event (Mormont et al., Reference Mormont, de Fays and Jamart2012) and felt that people with dementia had a right to know in order to begin treatment, face the condition positively, know what is happening to them, and plan for the future (Zou et al., Reference Zou2017). Carers were divided on whether the diagnosis should be revealed in an up-front approach, or in stages (Mastwyk et al., Reference Mastwyk, Ames, Ellis, Chiu and Dow2014). Those who preferred an up-front approach felt it necessary for planning and managing issues such as driving cessation. Carers felt empowered when HCPs explained how and where to get treatment (Mastwyk et al., Reference Mastwyk, Ames, Ellis, Chiu and Dow2014) and tended to prefer the HCP openly informing the person with dementia of the diagnosis (Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen2008). A good quality disclosure was associated with better carer adjustment in relation to sadness, depression, and acceptance (Woods et al., Reference Woods2018).

Only two studies considered attitudes toward diagnosis disclosure from the perspective of people with dementia themselves, with one finding that people with dementia tended not to agree with or acknowledge the information disclosed by the HCP (Peel, Reference Peel2015). The other study found that people with dementia would prefer to receive a direct disclosure even though it might be a shock (Mastwyk et al., Reference Mastwyk, Ames, Ellis, Chiu and Dow2014).

Use of diagnostic tests and assessments

Four studies suggest that, prior to the disclosure meeting, HCPs should discuss what people with dementia and carers can expect from assessments, especially from brain scans and biomarker testing, and potential limitations or implications of diagnostic tests (Visser et al., Reference Visser, Wolf, Frisoni and Gertz2012; Porteri et al., Reference Porteri, Galluzzi, Geroldi and Frisoni2010; Grill et al., Reference Grill2017; Lingler et al., Reference Lingler2016). People with dementia and carers should have the choice to receive the results from assessments or not and should have the opportunity to change their mind at any point (Porteri et al., Reference Porteri, Galluzzi, Geroldi and Frisoni2010).

Three studies suggested that brain scans should be reviewed in disclosure meetings (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen2018; Lingler et al., Reference Lingler2016; Grill et al., Reference Grill2017), so people with dementia and carers can see the images. Two studies offered caution regarding how results of amyloid scans were communicated, where explanations should state that presence of amyloid indicates a risk for developing dementia while absence of amyloid does not indicate absence of illness (Grill et al., Reference Grill2017), and that biomarkers are not yet a diagnostic tool in themselves (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Johnson, Liebmann, Bothwell, Morris and Vidoni2017). One study advocated for provision of take-home materials to supplement the explanation of scans and assessments (Lingler et al., Reference Lingler2016).

Truth telling and deception

Three studies considered the aspect of truth telling or withholding the truth of the diagnosis from people with dementia. One study reported that HCPs felt a truthful diagnosis was not necessary due to a lack of effective treatments and potential impact on preexisting symptoms of anxiety or depression (Porteri et al., Reference Porteri, Galluzzi, Geroldi and Frisoni2010). Conversely, a different study found that providing a truthful diagnosis did not create a negative emotional impact for people with dementia or carers and instead helped to relieve anxiety or depression for both (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter2008). The third study reported difficulties in delivering the diagnosis as people with dementia may try to normalize their experience, and HCPs must balance this with not deceiving the person with dementia as to the diagnosis (Peel, Reference Peel2015).

Timeliness

Three studies considered the timing of receiving a diagnosis of dementia, with one study reporting that nearly half of carers surveyed across five European countries felt diagnosis was delayed (Woods et al., Reference Woods2018). Reasons for delay included people with dementia refusing to be assessed, negative professional attitudes, and being told there was no point in a diagnosis. Receiving timely diagnoses could assist people with dementia in remembering their diagnosis (Bradford et al., Reference Bradford2011), but another study indicated potential detriment to well-being if provided before a person had processed what is happening and accepted the changes they are experiencing (Vince et al., Reference Vince, Clarke and Wolverson2017).

Training and skills

As far as can be determined from the included studies, there is no specific training available in how to disclose a diagnosis of dementia. In two studies, HCPs reported receiving training in breaking bad news, attending conferences on the topic, or using general guidelines for diagnostic disclosure (Vince et al., Reference Vince, Clarke and Wolverson2017; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen2018). Despite disclosure often being performed by specialists, two studies indicated that PCPs should have training on disclosing sensitively (Foley et al., Reference Foley, Boyle, Jennings and Smithson2017) and integrating disclosure into their consultations (Villars et al., Reference Villars2010).

Discussion

This review provides the only up-to-date comprehensive account, based on a rigorous systematic literature search, of common practice around the world in disclosing a diagnosis of dementia from the perspectives of people with dementia, carers, and HCPs. These findings suggest that telling the person with dementia the diagnosis is now common practice. However, HCPs may experience discomfort in revealing the diagnosis and consequently use euphemisms to describe the syndrome rather than explicit terminology. Generally, if diagnosis disclosure is provided as a one-off event, and without discussion of hopeful aspects or emotional rapport building, it has a negative impact on people with dementia and carers. Carers report needing to know more about the future and prognosis, and their preference is for the diagnosis to be disclosed in a realistic yet hopeful way. HCPs would benefit from guidance and support in how to disclose the diagnosis, and the disclosure should be approached as a process involving a multidisciplinary team rather than as a singular event. The findings suggest progress in normalizing the diagnosis and reducing stigma but highlight that there is still more to be done.

Disclosure was viewed as a negative process by HCPs who reported an attitude of hopelessness, and uncertainty around the exact diagnosis, prognosis, and how much people receiving the diagnosis already knows or can understand. HCPs highlighted that the information needed by people with dementia and carers is difficult to deliver due to the delicate balance between honesty and hope (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Dooley and Mccabe2016). HCPs do not appear comfortable with their position as someone who delivers bad news and can only provide limited treatment options. This review also identified that little consideration was given to patient-centered communication and expectations extending to cultural differences.

Our findings suggest that disclosures can cause people with dementia to suffer emotionally (Zou et al., Reference Zou2017). Similarly, emotional rapport building is identified as important yet may not be frequently used in disclosures (Zaleta and Carpenter, Reference Zaleta and Carpenter2010), suggesting that HCPs are not prioritizing the emotional impact of receiving a diagnosis as a key consequence of the meeting. While disclosure tended to have a negative impact for people with dementia and their carers, carers did report that disclosure was a useful event that enabled them to organize treatment and support, and discussion of etiology, progression, and causes was helpful. However, carers expressed a need to know more about the future and prognosis following diagnosis. This finding shows consistency with a previous review (Werner et al., Reference Werner, Karnieli-Miller and Eidelman2013), but the present review shows a step forward in the dialog around truth telling, in that simply knowing the diagnosis itself is not enough. Carers need to know what will happen to the person with dementia in the future, beyond the diagnosis, and what ramifications this will have for themselves as carers.

Consistent with earlier reviews (Lecouturier et al., Reference Lecouturier2008; Werner et al., Reference Werner, Karnieli-Miller and Eidelman2013) is the preference for a process approach to disclosure. This is supported by guidance from the UK Alzheimer’s Society (Alzheimer’s Society, 2018) and the British Psychological Society (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Mccabe and Guss2018) which suggest that delivering information in one session is overwhelming and instead disclosure should be embedded within the care pathway. People with dementia and carers need more time and space to process information provided in the disclosure, which could be achieved using follow-up appointments. Using follow-up appointments could aid with retaining information, as in the general population 34–88% of what is said in medical appointments is forgotten, depending on the type of information provided, where general recall is higher for a discussion, but lower for specific information such as regarding lifestyle interventions (Richard et al., Reference Richard, Glaser and Lussier2017). This is important, given the range of topics covered in a diagnosis disclosure, and it is likely that this figure is higher for people experiencing cognitive changes. More opportunities to impart the same information, or presenting smaller amounts of information more than once, could help people remember the diagnosis and its implications, while providing space to explore the emotional impact of the diagnosis. However, it must be noted that increasing the number of appointments would require greater resources, without which an increase in waiting times is likely and this is not desirable either. Involving other agencies, such as third sector agencies, could be useful.

Strengths and limitations

This review used a comprehensive search strategy across several databases to identify as many relevant papers as possible, although some papers indexed in other databases may have been missed. The rigor of the systematic search and quality review can be seen in that searching was completed by two reviewers, allowing for discussion and justification for inclusion or exclusion of each paper, and a sample of papers were assessed for quality by a third, independent reviewer which resulted in a high level of agreement. Quality assessment was not used in previous reviews of this topic area (Werner et al., Reference Werner, Karnieli-Miller and Eidelman2013), and showing how this review has moved the discussion forward by highlighting methodological issues that must be considered in future work. Despite studies being of a variety of designs and conducted in different settings, the findings are generally consistent, suggesting that this review has identified realistic trends. The perspectives of people with dementia, carers, and HCPs were captured in this review, ensuring that findings are relevant to the experience of all people involved in the disclosure, and any implications can consider each set of needs.

Only studies written in English were included, and therefore some findings may have been missed. However, studies from across the world were included and despite some contradictory findings, generally there was agreement, suggesting that studies in languages other than English may not have significantly changed the results if included. Studies of all designs were included and, although this renders it impossible to synthesize numerical findings into meaningful quantitative analyses, the integration of qualitative and quantitative findings should be considered a strength. One methodological consideration to acknowledge is that much of the research included in this review is reliant on self-report techniques, either through use of surveys or qualitative interviews. While surveys can reach a broad audience, and interviews can elicit rich details about the experience of disclosure, both methods of data collection can be affected by bias, and it is challenging to reliably compare or contrast practices reported by HCPs with the impact they have on recipients (Plejert et al., Reference Plejert, Jones and Peel2017). Only 8 of the 52 included studies used observational methods (Hillman, Reference Hillman2017; McCabe et al., Reference Mccabe, Pavlickova, Xanthopoulou, Bass, Livingston and Dooley2019; Peel, Reference Peel2015; Sakai and Carpenter, Reference Sakai and Carpenter2011; Wynn and Carpenter, Reference Wynn and Carpenter2017; Xanthopoulou et al., Reference Xanthopoulou, Dooley, Meo, Bass and Mccabe2019; Zaleta and Carpenter, Reference Zaleta and Carpenter2010; Zaleta et al., Reference Zaleta2012).

Implications

Recommendations for clinical practice

Communication skills do not reliably improve with experience alone (Cantwell and Ramirez, Reference Cantwell and Ramirez1997) and consequently further training, supervision, and regular reflection on practice may support HCPs in navigating uncertainties and managing their own emotional journey. For HCPs in specialist roles, training should be specific to disclosing a diagnosis of dementia rather than generally about breaking bad news, and supervision should cover managing the emotions of the person with dementia and the carer, as well as their own emotional responses. Communication skills training is mandatory in the majority of training programs for all HCPs (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Rivera, Bravo-Soto, Olivares and Lawrie2018), but training to develop skills in shared communication, to raise awareness of supporting people with dementia and carers to assert themselves and maintain their agency and power during the disclosure, is needed. HCPs may benefit from guidance in understanding and supporting cultural differences and sensitivities in diagnosis disclosure. However, it is recognized that training is resource-intensive and relies upon having appropriately trained individuals who are available to train and support others. This is likely to be difficult across disciplines and in time-pressured healthcare environments.

Pre-diagnostic counseling prior to disclosure could explore beliefs and expectations and potentially mitigate negative impacts by ensuring people with dementia and carers are prepared. This may support people with dementia and carers to consider questions they could ask between meetings and provide greater opportunity to speak during disclosure meetings. Follow-up meetings could enable tailoring of information, an opportunity to reconfirm the diagnosis, and discussions of prognosis, future considerations, and access to local support. Involving multidisciplinary teams could help to provide an holistic and hopeful disclosure, reducing the negative emotional burden on individual HCPs while also reducing the likelihood that the disclosure is viewed as a singular negative event by people with dementia and carers (Vince et al., Reference Vince, Clarke and Wolverson2017). Reassurance and a realistic sense of hope about the future should be emphasized throughout, and HCPs could discuss how people with dementia and their carers can maintain quality of life after diagnosis.

Recommendations for people with dementia and carers

Information about memory assessments and what typically happens could be provided through channels including posters or leaflets in GP surgeries and community spaces. Information about what to expect when receiving the results of assessments may be provided ahead of disclosure meetings, although this could be distressing if information were given without having someone available to provide support or further explanations. People with dementia should be supported to ensure they can have someone attend the disclosure meeting with them if they wish. Encouraging people with dementia to arrange a follow-up appointment with their GP could be beneficial for asking further questions and considering the future implications.

Recommendations for research

Much of the research included in this review relies on recalling the disclosure experience, and there is disparity between viewpoints of people with dementia, carers, and HCPs. A sensible next step is to conduct research that directly observes disclosure meetings, considering all individuals involved. While work in this area has already been undertaken involving people with dementia, carers, and HCPs (Peel, Reference Peel2015), further work currently underway focuses on doctors only (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Dooley and Mccabe2019; Xanthopoulou et al., Reference Xanthopoulou, Dooley, Meo, Bass and Mccabe2019). More research that considers the three-way dialog between people with dementia, carers, and HCPs, analyzing what each brings to the disclosure and what each takes away, is needed. Most research to date is from the perspective of carers, with some from the perspective of HCPs. More research considering perspectives of people with dementia on diagnosis disclosure is needed to fully understand their wants and needs. Research combining all three perspectives is required to develop a realistic understanding of how disclosures can be best conducted to benefit everyone involved, more closely reflecting real practice.

Researchers must respect the agency and rights of people with dementia to participate in research. Earlier reviews (Werner et al., Reference Werner, Karnieli-Miller and Eidelman2013; Lecouturier et al., Reference Lecouturier2008) have not explored power dynamics between individuals involved in disclosures, or the agency that people with dementia possess in the interaction. Only two studies in this review specifically considered attitudes toward diagnosis disclosure from the perspective of the person with dementia, although other studies have explored difference facets of the disclosure process. Less than half of the studies in this review recruited people with dementia, and of those that did, the number of participants with dementia was small. Developing an understanding of disclosure without involving people with dementia is inconsistent with patient-centered care. The lack of information regarding cultural differences in disclosure clearly shows that future research must explore this area to develop practices that support a culturally sensitive disclosure process.

Future qualitative studies could demonstrate greater methodological quality by stating the underpinning philosophical perspective adopted by researchers during data collection and analysis, including reflexive statements to locate researchers culturally and theoretically. Increased awareness by journal editors and peer reviewers regarding the reporting of qualitative methodology would encourage researchers to be transparent in their theoretical approaches.

Conclusions

Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia is a key process for people with dementia, carers, and HCPs. This review indicates that while changes in some aspects of disclosure have occurred over the last decade, disclosing a diagnosis of dementia remains a difficult and complex process, for which formal training and guidance is lacking. Receiving a diagnosis is generally a negative process for people with dementia, carers, and HCPs and leaves carers in particular feeling uncertain over the prognosis and future of the person they care for. Pre-diagnostic counseling and follow-up appointments could enable realistic and hopeful discussions of the implications of receiving a diagnosis of dementia, while reducing emotional burden on HCPs. This review highlights a need for more objective evidence that considers the perspectives of all individuals involved.

Conflict of interests

None.

Author contributions

JY and MS conducted the systematic review and the quality analyses of the included articles. JY wrote the article and MS, RS and LC all contributed to writing the article. All authors designed the review.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alexander Humm (AH) for assisting with the quality review process.