Introduction

Since the global COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, care homes across the world have taken restrictive measures to stem infection rates and safeguard their vulnerable older adult residents. In the UK, there was no government guidance on how care homes should operate and how they should enable family visitation, leading care homes individually to all close down to outside visiting from February 2020 onward. Throughout the pandemic and in between waves one and two, care homes in the UK have made individual decisions of how to ease and then tighten visiting rules again. In the UK, there was a substantial lag before effective and sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) was available for staff, residents or visitors. There was a significant outbreak of COVID-19 in almost 7000 English Care homes (44%) between 9 March and 19 July 2020 with 19,286 deaths of care home residents involving COVID-19 between mid-march and mid-June 2020 (Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2020), and a further 16,355 in wave two from 1 November 2020 to mid-February 2021 (35,641 in total) in England and Wales (Nuffield Trust, 2021). In the Netherlands, both during the first and second wave, over 800 Dutch care homes had a COVID-19 outbreak (approx. 35%). Care home residents have been most affected by COVID-19, with approximately 50% of all COVID-19 deaths during the first wave occurring within care homes, estimated at 7,400 COVID-19 deaths in care homes (29% of total deaths in care homes) (Inzitari et al., Reference Inzitari2020). During the first wave of COVID-19, restrictive measures in the Netherlands included a total ban for visitors to care homes. This total lockdown of care homes lasted 2 months, after which a national pilot was started to cautiously reopen care homes for visitors. In a selection of homes, one visitor per resident was allowed.

Many care home residents are aged 65+ years and some live with dementia. Evidence is starting to emerge on how the pandemic and associated restrictions are impacting on people living with dementia in general, focusing on those residing in the community (Giebel et al., Reference Giebel2021; Giebel et al., Reference Giebel2021; Talbot and Briggs, Reference Talbot and Briggs2021; Thyrian et al., Reference Thyrian2020). People with dementia are found to deteriorate faster during lockdowns and restrictions in their own home, being confined to their place of residence and not receiving external face-to-face social support. This is also impacting on the mental well-being of family carers, as carers have to take on additional caring duties (Hanna et al., Reference Hanna2021). Evidence on the impact of the pandemic on care home settings is sparser however, with little evidence to date on how residents are faring during continued lockdowns of care homes and changing restrictions.

Verbeek et al. (Reference Verbeek2020) was the first study to report on compliance and experiences with allowing visitors back into nursing homes after a ban during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. The study showed that in general the experiences with reopening the nursing home for visitors was very positive. Furthermore, even though there were national guidelines, there was diversity among nursing homes with regard to the use of PPE, and the arrangements of the visits. Findings from this study were mainly based on a questionnaire and interview with formal contact persons in different nursing homes. The authors of the study indicated that more research is needed into in-depth experiences of family, residents, and staff in order to investigate the impact of the visitor ban and the reopening of nursing homes. A subsample of those nursing homes was monitored during reopening using a digital questionnaire, on-site observations and in-depth interviews (Koopmans et al., Reference Koopmans2021). While reopening appeared to be beneficial to the well-being of residents, healthcare professionals expressed concerns over increased risks of infection while acknowledging the benefits of reopening. This is supported by more research emerging on infection transmission of COVID-19 in care homes (Burton et al., Reference Burton2020; Stall et al., Reference Stall, Jones, Brown, Rochon and Costa2020), as opposed to the experiences and psychological impacts of lack of visitations on family members and residents. However, research across the globe indicates the fine balance that needs to be struck between managing infection risks and quality of life for residents (Ayalon and Avidor, Reference Ayalon and Avidor2021; Sizoo et al., Reference Sizoo, Monnier, Bloemen, Hertogh and Smalbrugge2020; Van et al., Reference Van der Roest2020). In particular, residents and carers appear to face high levels of emotional burden due to care home closures to the outside world (Ayalon and Avidor, Reference Ayalon and Avidor2021; Van et al., Reference Van der Roest2020), while a small Delphi panel made up of 21 USA and Canadian post-acute and long-term care experts yielded five recommendations for care home visiting during the pandemic, including stringent infection control measures, enabling visits, and limited physical contact between family members and residents (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman2020). Thus, drawing together findings from individual countries has highlighted to date the need for safe visiting in care homes (Low et al., Reference Low2021). However, there appears to be a lack of qualitative cross-country data comparing the experiences of different types of care home visitation during the COVID-19 pandemic so that comparisons between different countries is important to make the best use of existing knowledge to further advance care for residents during the pandemic and beyond.

The aim of this international study was to explore the experiences of family members of care home residents regarding care home visiting during the COVID-19 pandemic and compare these between the UK and the Netherlands. The Netherlands appears to have been the first country to have implemented consistent guidance for care home visitation during the pandemic and indeed has been the only country to mandate the reopening of care homes to visitors (Low et al., Reference Low2021). In contrast, there has been a lack of clear guidance on care home visitation in the UK. This provides an important perspective for exploring how care home visits were undertaken in different countries and their potential variations and similarities in affecting family members of care home residents. Despite varied degrees of vaccine rollouts across the globe, COVID-19 is going to remain an environmental infection threat for some time to come, particularly in the light of continued new virus strains developing which may render vaccines ineffective, access to vaccines worldwide and antivaccination movements.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

Family carers aged 18+ years with a relative residing in a UK or Dutch care home were eligible to take part. In the UK, unpaid carers were recruited via third sector organizations, targeted emailing of care homes as part of the NIHR ENRICH network, a network of research-ready care homes, as well as via social media. At the point of data collection, there were different restrictions in place for each care home, while during November, care homes went into full lockdown. In the Netherlands, family carers who visited their family member at the beginning of the cautious reopening were informed about the study while they were receiving information on the regulations and guidelines with regard to their visit (via phone, and again right before the time of the visit). Immediately after the visit, the family carers that were willing to participate, were asked to perform a short interview (after signing an informed consent). In addition, potential participants were asked if they were willing to participate in a more in-depth phone interview 1 week after their first visit.

Ethical approval was obtained prior to study begin from the [BLINDED] ethical committee in the UK [Ref: 7626], and from the ethics committee of [BLINDED] (2020-6549) in the Netherlands.

Data collection: Data and procedure

Our data comprise of three parts – in-depth interviews from the UK were conducted between October and November 2020. Short interviews and in-depth interviews from the Netherlands were both conducted during May 2020. The short interviews were conducted immediately after the first visits since the lockdown. The in-depth interviews were performed within 1 week following the first visit. While studies in the UK and the Netherlands were conducted separately, they focused on the same topics in both countries and were thus comparable.

In the UK, topic guides for family carers and for care home staff were co-produced in a team of academics, clinicians, service providers, and unpaid carers of people living with dementia who have experience of care homes. Topic guides involved questions surrounding their experiences of visitation, how the pandemic has changed different aspects of seeing their relative with dementia in the care home, communication from the care home, as well as safety procedures and how care provision has changed for care home staff compared to before the pandemic, and how they experience residents to experience these changes. Appendix 1 includes all topic guides.

In the Netherlands, short interviews were aimed at capturing the experiences of the family carers during the lockdown and their first visit to the nursing home after the lockdown. The focus was on the impact on their well-being, and the possibility to comply with all guidelines that were in place (e.g. 1.5 m distance during the visit, no touching, wearing a mask, etc.). The short interviews were held for 5 consecutive days. A group of researchers was present at a nursing home during the first 2 to 3 weeks of the reopening. All nursing home residents were scheduled to receive a visitor once during the first week, where they had a visitor. Unpaid carers who were scheduled to visit the nursing home were informed about the presence of the research team and were asked to provide consent for having a short interview with one of the researchers after they visited their family member.

In addition, in-depth interviews were scheduled with participants who already took part in the short interviews. Short interviews therefore provided the first picture of the experiences, which was more extensively elaborated on in longer follow-up interviews for some family carers, with both together providing a rich picture of the nuanced experiences of carers. Furthermore, in four other care homes, visitors were asked to participate in an interview by telephone which was to be held within a few days after the visit. During this in-depth interview, participants were asked about the process of planning their visit, the communication regarding the visitation, and again, compliance and impact on well-being were discussed.

Data analysis

Background characteristics are described using frequency analysis in SPSS Version 25. The interviews were summarized in a brief transcript (for the short interviews) or in a structured response sheet (for the in-depth interviews). In these response sheets, (short) summaries on the response of participants were given for each of the posed questions. Next, the data were analyzed thematically within the research team using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Open codes were given to sentences or paragraphs within the summaries, after which codes were grouped into overarching topics/themes. The codes and themes were discussed repeatedly in order to reach consensus on the most relevant themes with regard to the research question.

Public involvement

Carers and people with dementia were involved in different aspects of this study in the UK. Three current and former carers were involved in all elements of this study, from conceptualization to conduct, analysis and dissemination. Public advisers, who were reimbursed for their participation, helped develop the topic guides, ensuring that the questions asked captured the important points in the lives of family members with relatives residing in care homes. There was no public involvement in the Netherlands research planning and delivery.

Results

Background characteristics

A total of 125 family carers (99 Dutch; 26 UK) participated in the study. Of the 99 Dutch interviews, 65 short interviews lasting between 5 and 15 minutes and 34 in-depth phone interviews lasting between 30 and 40 minutes were conducted. Table 1 provides some background demographics of the interviewed carers. In the UK, the majority of carers were female (69.2%) and adult children of the care home residents (61.5%). In the Dutch sample, demographics were gathered on the participants of the in-depth interviews (n=34). Half of the included carers were male and half were female. The majority (70%) of carers were the adult child of the resident.

Table 1. Participant characteristics of the Dutch in-depth interview and the UK sample

Qualitative findings

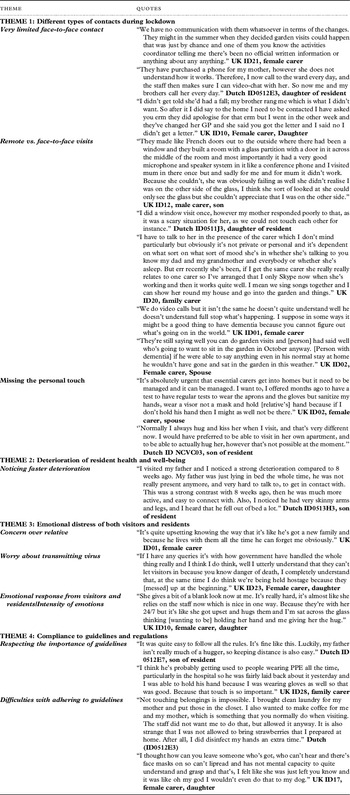

We developed four themes using thematic analysis: (1) different types of contact during lockdown; (2) deterioration of resident health and well-being; (3) emotional distress of both visitors and residents; and (4) compliance to guidelines and regulations. Quotes for each theme and subtheme are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Qualitative quotes by themes and subthemes

THEME 1: Different types of contacts during lockdown

Very limited face-to-face contact

In the UK, many carers were not allowed face-to-face visits either since the pandemic started or at different time points of the pandemic. Some were allowed to have face-to-face visits in the garden, in customized pods or through windows, and a rare exception was for a carer to visit their relative in their room. Where visits were allowed, care homes had booking systems in place to manage the number of people in the homes at any time, as well as care home staff to facilitate visits with family members. Similarly, in the Netherlands, relatives indicated that during the lockdown they had no face-to-face contact with their relatives. However, the majority of respondents from both countries indicated that the nursing homes employed creative solutions to stay in contact with each other. Respondents talked about the possibility to have window visits, to talk over the phone on a regular base, sharing information via internet platforms, and to talk to their loved ones via video calling.

In the UK, some carers noted preferential visiting rights by some family members, while they themselves were not allowed to go in or only rarely. This caused some frustration, as care homes also failed to communicate why certain residents were allowed more visits than others. In the Netherlands, during the reopening of the nursing homes, each resident was allowed only one visitor. However, most respondents indicated that it was quite straightforward to decide who this person would be (as most of the time there is a “first responsible family carer”).

Remote vs. face-to-face visits

Both remote and the new pandemic-created face-to-face visits seemed to be of much less benefit to family members and residents as opposed to true face-to-face contacts experienced and enjoyed prior to the pandemic. In both countries, respondents indicated that visits were more beneficial than remote engagement; however, these also had their downsides. Garden visits, for example, were weather-dependant, and if the weather was not suitable, window visits were conducted instead, where care homes enabled these. There was an issue for some residents who were not living on the ground floor, being excluded from window visits and causing further distress to the new forms of alternative visiting forms. Many carers shared how their relative with dementia was unable to understand socially distanced face-to-face visits or hear their relative from a distance, highlighting how alternative visiting options could not replace real face-to-face contacts.

Where remote contact was enabled digitally, such as via skype, there was rarely any privacy, as care home staff had to support the resident in using a phone or tablet, and often with limited understanding from the resident. Carers expressed concerns about being unable to have a private conversation with their relative. Pod visits similarly offered little privacy, highlighting overall how different types of COVID-19 visits have changed the dynamics, compared to visits in the resident’s room for example.

Some carers noted that the types of visits that were allowed would not have been taken up by the residents if it was pre-pandemic. For example, one UK carer explained that her husband would never have sat in the garden, so having a pandemic garden visits would be of no use and benefit. Equally, pod visits or window visits would never have been used pre-pandemic and outside of an infection-controlled environment.

Missing the personal touch

While carers benefited to some extent from the socially distanced face-to-face visits, carers also expressed their upset about needing to hold their relative’s hand to feel close to them. Missing the personal human touch between family members and residents was also expressed as an issue where care home residents did not comprehend window visits and for example got agitated due to the inability to be close to their family member. Although in the Netherlands everyone was happy to be able to visit again, due to the guidelines of keeping distance, no touching, and the wearing of face masks, a visit was sometimes experienced as disappointing, difficult, or nervous.

THEME 2: Deterioration of resident health and well-being

Noticing faster deterioration

Carers in both countries noticed an increased deterioration in symptoms and the condition of their relatives with dementia during the pandemic and since lockdowns and other restrictions had commenced. This not only included the residents’ cognitive and physical symptoms, but also their well-being. Where some residents had been active before the pandemic, since then carers were complaining and concerned about the deteriorations in mobility within often relatively short periods of time, both in the Netherlands and the UK.

THEME 3: Emotional distress of both visitors and residents

Concern over relative

Many family members were concerned over their relative’s well-being and their relationship with them. The increased periods of being unable to visit their relative worried carers, especially where they received little communication from the care homes about their well-being. In effect, care home staff took on an unplanned new role of family, caring for the residents at all times and not allowing their real family to enter the care homes. This was heightened by the fact that all UK residents and many Dutch residents were living with dementia, and thus more likely to forget their own family members by being unable to see them on a regular basis.

Worry about transmitting virus

Visiting their relative posed mixed feelings to visitors. Many enjoyed visiting their relative but many were also scared of the risks posed by reopening care homes. Reopening care homes could result in increased risks of virus transmission, without sufficient testing and other restrictions in place, which left some carers accepting that care homes should stay closed in the UK. Others however, in the UK, were frustrated with the lack of visiting and were desperate for care homes to open their doors again to properly connect and communicate with their relative again.

Emotional response from visitors and residents/intensity of emotions

Visitors indicated that it was good to see each other after a long time. However, Dutch and UK experiences seemed to differ slightly in terms of emotional impact on both carers and residents. In the Netherlands, most residents were happy and comfortable during visits, whereas a few were sleepy/absent or confused. Face-to-face contact had added value, but relatives also mentioned that visits were different and less enjoyable than before due to the lack of physical contact and not being allowed to walk outside. Some residents got agitated not understanding why they could not touch their relative or why they were behind a window or screen. These negative experiences were reflected in many UK carers, with residents being agitated for a lack of understanding the physical distance and screens between them and their loved ones, leading to emotional upset in many carers.

THEME 4: Compliance to guidelines and regulations

Respecting the importance of guidelines

In the Netherlands, all respondents indicated to understand the importance to adhere to all the guidelines. The initial response of most participants was that it was easy to adhere to the guidelines. Similarly, UK carers expressed it was important to adhere to the guidelines. However, where the resident was in the end of life stages, carers were allowed to hold their relative’s hand with restrictions eased surrounding physical distancing.

Difficulties with adhering to guidelines

While family carers mostly respected the guidelines, some family members also expressed how difficult it was to adhere to them in both countries. They missed the personal touch and struggled keeping a physical distance from their relative when on a face-to-face visit. It seemed unnatural to keep a distance from their relative who they have not seen for a long time. Others also mentioned the difficulties of wearing masks when on visits, and the difficulties in engaging with their relative this way, as the person with dementia cannot see facial features and the family member smiling for example, and also may struggle recognizing the family member. This was also raised by a UK family carer in light of staff wearing PPE in the care homes which appeared to cause difficulties and in the carer’s eyes, a care neglect.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to explore the impact of the pandemic on visiting care home residents and comparing the experiences across two cultural settings. While remote and the new normal alternative types of face-to-face visits were available, they were unable to replace genuine face-to-face visits in both countries. The difference between countries was that the Netherlands had quickly implemented blanket guidance on care home visitation, enabling a faster and smoother transition to reuniting family members with residents again.

Removing any face-to-face contact between family members and residents and creating a care home contact bubble has detrimental effects on the well-being of both parties involved. During the pandemic, alternative face-to-face visits such as window, pod, or garden visits have become the norm, where they were available and enabled by care home staff. In addition, remote digital connections between family members and residents also have become the new norm, reflecting what has occurred in community settings for people with dementia and carers trying to engage with support services (Arighi et al., Reference Arighi2021; Giebel et al., Reference Giebel2021).

While these were a lifeline to stay in contact with relatives to some degree, many family members faced difficulties in engaging with different face-to-face visits in the UK. This was because of a lack of clear guidance for care homes, whereas in the Netherlands, guidance was released and implemented early on in the pandemic in May 2020. Thus, comparing the data from these two countries with very different levels of government input as to how visiting should operate, findings indicate how Dutch family members have benefited to a greater degree from these alternative visits, leaving many UK family members excluded from care homes for long periods of time.

While guidelines were helpful in the Netherlands in enabling visits relatively early on in the course of the pandemic, family members in both countries expressed how they respected and understood the general public health measures (such as social distancing, wearing PPE). However, they also raised the difficulties they experienced by not holding a relative’s hand on a visit especially for those with sensory deficits. Considering the emotional turmoil experienced by lack of contact between residents and family members, and the restricted nature of contact. Findings indicate the significance of social contact and their impact on mental well-being, as evidenced outside the care home sector during the pandemic and in pre-pandemic times (Domenech-Abella et al., Reference Domenech-Abella, Mundo, Haro and Rubio-Valera2019; Cations et al., Reference Cations, Day, Laver, Withall and Draper2021; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Russo, Campos and Allegri2020). This is also captured in a recent international report on the care home visiting, which provides five major recommendations which are corroborated by our findings: avoiding blanket visitor bans; safe alternative face-to-face visits; essential partner status for family carers; government support for implementing safe visiting; and ensuring the human rights of residents are met, not depriving them of their basic rights of seeing friends and family (Low et al., Reference Low2021). Restrictions in care homes thus need to be mindful of the individual resident’s needs, rather than a blanket ban on family members per se. If not, care homes indeed risk, and have risked, human rights violations, also in light of quarantining residents with dementia against their will (and understanding) (Iaboni et al., Reference Iaboni2020) so that Low’s et al.’s (Low et al., Reference Low2021) recommendations should be implemented across care homes, particularly in countries where governmental guidance is missing.

This lack of government guidance has left care homes across the UK, and globally, without clear guidance about how to manage infection risks as well as to manage the residents’ well-being or justify the choices they make in this regard. There was no clear guidance on how to provide care safely to residents, and care homes had to come up with their own strategies of how to deliver care, but also how to enable or minimize outside visits (from family members and friends) in order to reduce the spread of the virus. In addition, procuring PPE remains a significant issue for many care homes and social care staff more broadly (Carter, Reference Carter2020; McGarry et al., Reference McGarry, Grabowski and Barnett2020). Without any guidance, and staff more likely to work across different care homes, infection risks and COVID-19 outbreaks are higher (Ladhani et al., Reference Ladhani2020). Thus, a key message from this pandemic and from this study is the importance of clear communication to care homes, and family members, in case of future pandemics or future waves of COVID-19.

While data were collected prior to vaccination rollouts, findings have implications for vaccination ready care homes as well, as well as for new COVID-19 waves with new variants which are not targeted by current vaccines. In light of a large vaccination roll-out in the UK since early December 2020, from 8 March and the 29 March 2021, one and two essential visitors, respectively, have been allowed into the care homes again while strictly adhering to public health guidance. Although this guidance was released, it was not implemented in all care homes in March, with factors of low uptake of vaccination in care home staff likely also affecting family visitation (Giebel et al., ). In contrast, in the Netherlands, it is now illegal to impose a full lockdown on care homes, something that has not been enshrined in law in the UK, yet. However, there is no evidence to date on how these guidelines are implemented in practice, and future research needs to explore the effects of vaccinations and new visitation rules on residents and family members.

While this study benefits from a cross-country exploration of the topic and thus wider representativeness of the findings, it is to be noted that this study only focused on family carers. These also shared an insight on how residents were faring during those visits, but findings are restricted to their perspectives. Considering the barriers of getting ethical approval to conduct interviews with residents in the UK, linked with the inability to go into care homes to collect data, obtaining the views from family carers are a suitable avenue of obtaining data. Family carers completing a short interview in the Netherlands were all from one care home, thereby reducing the wider representativeness of the short interviews while providing a rich picture of the different experiences of family carers. Longer interviews were conducted across different sites. Another limitation is that the topic guides in both countries were not the same, yet asked similar questions and thus focused on the same topic, making it possible to compare the data from both studies.

Conclusions

Care homes require clear guidance to be able to deal with infection control effectively and manage new ways of care delivery. While new forms of visiting, such as window and pod visits, as well as remote digital connections, do not provide the same level of connection between family members and residents as pre-pandemic face-to-face visits do, enabling these well and frequently to all family members and residents can help reduce some of the emotional burden felt by lack of contact. Considering patchy vaccination roll out worldwide, and new variants found regularly which may impede the benefits of existing vaccinations, we can take important learnings from this international study and provide strong recommendations for improved, early, and clear guidance for care delivery and visitation, and the enablement of (alternative) face-to-face visits as much as possible. The early implementation of care home visitation in the Netherlands has highlighted the benefits of care home visitation, if properly supported through information and support for visitors, staff, and residents, which should be provided in future outbreaks in care homes across the world.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the participants who shared their experiences as part of this study, highlighting the issues surrounding care in the time of COVID-19.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

This study was funded by the Geoffrey and Pauline Martin Trust, with funding awarded to the principal investigator. This is also independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast (ARC NWC). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care. The Dutch study was funded by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sports. The research was coordinated by the University networks of Radboud University Medical Centre and Maastricht University; data have been collected by six University networks in the care for older people.

Description of author roles

CG conceptualized and led the study, CG, MG, and PM designed the topic guide jointly in the UK and discussed the findings jointly, BdB, HV, DG, and AS designed the topic guide in the Netherlands, BdB analyzed the data, CG and MG analyzed the data in the UK, CG and BdB compared the findings across the countries, CG wrote the manuscript, and all co-authors approved drafts of the manuscript and the final version.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610221002799