Does war deepen gender differences in politicians’ behavior or help erase them? Despite a large literature on gender and representation,Footnote 1 a growing literature on the role of women in conflict and postconflict politics,Footnote 2 and an emerging literature on women's and men's leadership during crisis,Footnote 3 we do not know much about the behavior of women versus men politicians in response to armed conflict. Are politicians more likely to follow gender stereotypes as conflict begins, or does a large-scale military conflict disrupt traditional gender roles among them?

Observing politicians’ behavior in real time, as conflict unfolds, to identify whether war changes behavior differently for women and men is important because who engages and how in response to conflict could have significant consequences for how the conflict unfolds, how long it lasts, whose concerns are heard and represented, and so on. Women's engagement during conflict relative to men's could also affect their presence and role in the postconflict recovery process, where women's leadership has been shown to decrease violenceFootnote 4 and help with postwar reconstruction.Footnote 5 That the number of active conflicts is at a historic highFootnote 6 further highlights the pressing need to understand how women and men politicians behave during war.

Prior work suggests that women's political engagement increases after war because large-scale military conflict disrupts patriarchal networks, transforms gender roles,Footnote 7 and offers women opportunities to gain leadership skills.Footnote 8 But this argument is less applicable to politicians’ behavior at conflict onset, before the effects of war have materialized. Emerging scholarship on women's participation in armed conflict, in turn, suggests that women and men behave similarly in conflict: they have similar motivations to join,Footnote 9 and women often perform similar roles and perpetrate similar levels of violence as men.Footnote 10 However, this literature looks at combatants, and it is unclear whether these insights are applicable to civilian politicians’ behavior.

Instead, we draw inspiration from psychology's terror management theoryFootnote 11 to argue that violent conflict likely pushes politicians to conform more strongly with traditional gender stereotypes. According to this theory, adhering strongly to stereotypes helps individuals cope with death-related fears, which likely spike in response to conflict onset. This would lead politicians to conform to gender stereotypes, and generate a public demand for such conformity. Scholarship on social role theory,Footnote 12 in turn, suggests that such role conformity implies a preference for men in the public sphere. In short, to help manage terror, politicians are likely to seek social role congruity at the onset of conflict. This implies that, as the war begins, women politicians are likely to engage less with the public than men, and when they do engage, they are likely to express more positive, nurturing sentiments and address stereotypically feminine issues (that is, be more role-congruent).

The literature lacks credible evidence on the gendered nature of leadership in conflict, in part because gathering systematic data on the behavior of politicians in the challenging and volatile context of an ongoing war is hard. Furthermore, to identify war's effects on politicians’ behavior and guard against selection effects and confounding, the conflict onset needs to be unexpected, and one needs to be able to observe behavior in real time before and after that onset—conditions that are difficult to meet. We overcome these significant data challenges by focusing on the Russian invasion of Ukraine that began on 24 February 2022 and collecting data on politicians’ engagement on social media before and after that date.

Our corpus includes 136,455 Facebook posts by 469 politicians (81 women and 388 men) from 1 November 2021 to 1 June 2022. While these data are limited to a specific type of behavior—politicians’ engagement with the public on social media—they do allow us to systematically observe, for the first time in the context of an invasion, how each politician engages with the public on a daily basis. Furthermore, using interrupted time series analysis, we can see whether the conflict affected engagement patterns for women and men politicians differently.

We find that, at the onset of the invasion, both women and men politicians’ public engagement spiked compared to their level of engagement before the invasion. But the women's engagement did not increase as much as the men's, even though before the invasion they had engaged at the same rate. Women display more positive sentiment and focus more on stereotypically feminine topics, while men occupy the traditionally masculine sphere. In additional analyses, we show that gender biases among the public are also magnified in response to the Russian invasion. These results highlight that conflict onset deepens gender-stereotypical behavior among women and men politicians, as well as traditional gender-role congruence expectations among the public. We elaborate on the implications of these findings in the conclusion.

Gender Stereotypes and Role Congruence During War

According to social role theory, common gender stereotypes deem women to be affectionate, nurturing, and suitable for communal caregiving tasks, while men are seen as aggressive, decisive, agentic, and suitable for leadership roles.Footnote 13 These stereotypes regarding the essential traits of and appropriate roles for women and men are part of the broader cultural context in which politicians operate, and they generate biased expectations among individuals about role-congruent behavior from women and men.Footnote 14 As a result, in terms of politicians’ behavior, individuals tend to (a) prefer men as leaders in politics,Footnote 15 (b) see some policy areas as more “suitable” for men than for women, and (c) dislike role-incongruent behavior.Footnote 16

Politicians themselves may subscribe to these social norms, resulting in biases in their own actions and choices. Public expectations stemming from these norms likely further incentivize politicians to conform to gendered roles in their behavior, with men politicians commonly depicting themselves as strong leaders protecting their citizens from internal and external threats, while women politicians display caring behaviors.Footnote 17 This is also reflected in research showing that women parliamentarians tend to focus more on “women's issues,” which relate to caregiving and nurturing.Footnote 18 Other work similarly demonstrates that women politicians are more likely to avoid conflict and competition, and to be averse to aggression.Footnote 19

We expect conflict onset to magnify gender-stereotypical expectations and corresponding behaviors by politicians. This is in line with terror management theory,Footnote 20 which suggests that viewing groups stereotypically and showing a preference for individuals who conform to these stereotypes is a way to cope with death-related fears,Footnote 21 which spike in response to war. Stereotypes reduce fear and uncertainty because they are part of cultural worldviews and traditions that give people a sense of order, control, and stability.Footnote 22 This aligns with works that show an overall increase in preference for tradition, social dominance orientation, and authoritarian attitudes in threatening environments.Footnote 23

Note that the psychological need to manage terror is likely to be present among politicians as well as the general public. This means that, to manage their own terror, politicians are directly motivated to defer to gender stereotypes and adopt role-congruent behavior. The same threatening environment also magnifies biases among the general public, increasing their preference for role-congruent behavior by politicians. This can further compel politicians to comply with gender stereotypes. Such response to public preferences is not necessarily due to electoral incentives, which are likely not dominant in a chaotic wartime environment. Rather, politicians cannot be completely immune to public preferences due to the nature of their positions as public servants. Furthermore, politicians are not just electorally but also intrinsically motivated—they want to be impactful.Footnote 24 Public prejudice affects how effective and impactful a politician can be, and thus incentivizes politicians to choose roles where they face less prejudice.

There is a strong association between masculinity and combat.Footnote 25 Thus topics like national security and external threats are defined as “men's issues”—ones that men are arguably more interested in and stereotypically suited for,Footnote 26 making leadership during violent crisis more role-congruent for men than for women.Footnote 27 Studies show that individual preferences for men as leaders are indeed strengthened in the area of defense,Footnote 28 during times of threatFootnote 29 and crisis,Footnote 30 and amid lingering security concerns after war.Footnote 31 Our argument, derived from terror management theory, provides a rationale for why this relationship emerges.

In sum, prevailing gender stereotypes and the heightened demand for social-role congruence in response to violent conflict both suggest that when conflict begins, women politicians are more likely to cede the political arena to men. That is, in response to conflict onset, we expect men politicians to increase their engagement with the public significantly more than women politicians do (H1).

Stereotypes and expectations about role congruence also likely affect how women and men politicians engage with the public in times of war. In line with the foregoing arguments, conflict onset likely encourages women politicians to prioritize their feminine qualities over masculine ones, while the opposite is likely true for men. We expect this to be reflected in their communication styles, where, for women politicians, empathetic and positive language, and engagement with feminine issues, are seen as role-congruent and likely socially rewarded.Footnote 32 In short, in response to conflict, women are less likely to pursue communication styles and topics that can be viewed as manly, such as using a negative tone and engaging with masculine issues (H2).

Empirical Strategy and Data

Our empirical strategy relies on observing the behavior of Ukrainian politicians on the social media platform of Facebook before and after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. On the morning of 24 February 2022, nearly 200,000 Russian forces entered Ukrainian territory while firing missiles at cities in the central and western parts of the country, igniting one of the bloodiest conflicts of the century. This invasion has been called “the biggest threat to peace and security in Europe since the end of the Cold War,”Footnote 33 making it an important case to study in its own right. For us, this case also offers design advantages and is generalizable, as we detail in the supplementary material section 1 (S1). We also explain there how the timing and severity of the invasion came as a surprise to the public and experts alike,Footnote 34 which gives us a quasi-experimental setting where it is reasonable to assume that politicians’ behavior would not have changed but for the invasion. Interrupted time series (ITS) analysis of these data allows us to causally estimate the effect of the invasion on politicians’ behavior.Footnote 35

Facebook pervades the online sphere in Ukraine. A 2021 survey identified it as the most popular social media platform there, with approximately 65 percent of the sample logging on at least once a month and 43 percent saying it is their preferred source for news.Footnote 36 Importantly, a follow-up survey showed that 51 percent still logged on once a month in 2022,Footnote 37 which alleviates the concern that the invasion may have significantly altered Facebook usage or the way users engage with the platform. In contrast, the invasion had a noticeable impact on other platforms; for example, the use of Telegram increased after the invasion.Footnote 38

Using Facebook's CrowdTangle API,Footnote 39 we collect all posts between 1 November 2021 and 1 June 2022 by any office-holding Ukrainian politician with a public Facebook page that we were able to identify.Footnote 40 This collection window allows us to include data from at least three months before and after the invasion, ensuring we capture the effect of conflict onset as well as any time-variant trend. Our data set comprises 136,455 Facebook posts (24,714 by women politicians, 111,741 by men) from 469 Ukrainian politicians (81 women and 388 men). We translated all posts into English with the Google Cloud Translate API. For more details on the data set and the collection methods, see S1.

The CrowdTangle API includes information on the time of posting, allowing us to create time-series data. We then estimate the effect of conflict onset by employing ITS analyses of the form

where y it is the outcome for politician i at time t, E t is a dummy variable indicating the post-invasion period (invasion, coded 0 for before and 1 for after), S i indicates politician i's gender (woman, coded 0 for men and 1 for women). T E=0 and T E=1 are running variables for the days elapsed since the beginning of the time window and the invasion, representing the serial trends with ζ and η, referred to as time and time since invasion, respectively. Assuming that each politician will have a different baseline of posting frequency, we include random intercepts by politician. When calculating standard errors, we use the Newey-West estimator to correct for autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity in the error terms.Footnote 41

Our quantities of interest are the estimates of β, γ, and δ. β is the estimated effect of the invasion among men politicians. γ is the estimated difference in outcome between men and women politicians before the invasion. δ is the main effect of interest: the estimated difference in the effect of the invasion by gender.

Measures of Outcome Variables

We first examine the level of engagement by politicians before and after the invasion. We operationalize engagement as posting frequency: posts per politician per day (posts per politician), with politician-day as the unit of analysis.

To test the second hypothesis, we examine differences in how politicians communicate and perform two sets of quantitative text analyses. We create two post-level measures. First, we gauge positive sentiment by matching keywords from pre-existing dictionaries that score words on their positive or negative tone. To minimize measurement errors, we use four standard lexicons (Syuzhet, NRC, AFINN, and Bing). Each lexicon uses a different vocabulary and a different scoring system, but all of them use higher values to indicate more positive sentiments.Footnote 42 We calculate positive sentiment by (1) identifying, in each post, the words in our corpus that are present in a given dictionary, (2) assigning the corresponding scores (positive or negative) to those keywords, and (3) summing up the scores at the post level. This is done separately for all four dictionaries.

Second, we explore the substantive topics of posts by applying an unsupervised topic model, Top2Vec.Footnote 43 This unsupervised natural language processing algorithm uses word-document embedding vectors to identify clusters of documents with semantic similarity. The algorithm assigns topics at the center of each embedding cluster and allows researchers to substantively interpret topics using keywords and documents that are proximate to the cluster center in the vector space, representing the semantic similarity within the cluster. Top2Vec is useful in uncovering substantive topics in our data, especially when compared to dictionary-based approaches,Footnote 44 because the keywords in our data are context-specific and may not align well with existing dictionaries for political texts. For example, Ukrainian politicians often use “Molotov cocktail” to refer to the country's resistance efforts, and “Pechersk Lavra” (a historic monastery in Kyiv) to appeal to nationalistic sentiments. These connotations are very likely to be lost if we rely on matching keywords from pre-existing dictionaries.Footnote 45 Top2Vec alleviates this concern to an extent. With this method, we uncover 907 clusters of documents with semantic similarity.

Recall that our theory predicts that, in response to conflict, politicians increase their engagement with topics aligned with their prescribed gender stereotypes. A sizeable literature in political science classifies an issue as part of the feminine domain if the issue corresponds to traditional social roles for women.Footnote 46 Following this, we manually examined clusters and checked whether each related to one of three topics that prior research has labeled with clear gendered expectations: social aid; morale boost; and security.Footnote 47 The first two are part of a traditionally feminine issue space, and the third is traditionally masculine.Footnote 48

The first topic, social aid, refers to posts about the provision of government services in and out of wartime, evacuation and resettlement during wartime, calls for volunteers or donations, discussion of humanitarian infrastructural support systems, and so on. Women tend to be considered better able to deal with social and humanitarian issues like these,Footnote 49 which situates this topic in the feminine realm. The second topic, morale boost, includes posts that highlight the heroism and bravery of Ukrainians, try to boost morale in wartime, commemorate historical events, or celebrate Ukrainian traditions and domestic holidays. We consider this a feminine topic because joviality, particularly in difficult circumstances, is uniquely expected of women leaders.Footnote 50

The final topic, security, involves posts that notify the public of air raids; provide updates from the battlefield; discuss legislation on security; express concerns about explosion of nuclear plants or insecurity with respect to energy, food, or public health; or provide emergency information. We classify this as masculine because war, physical security, and emergency response are fields traditionally associated with men.Footnote 51

Results

We start by presenting the results for our first hypothesis, that after invasion men politicians will engage more with the public than women politicians do. We then test our second hypothesis, that women and men politicians respond to conflict in a gender-stereotypical manner in terms of tone and topics.

H1: Men Engage More than Women

First, we visually inspect the posting behavior of Ukrainian politicians before and after the invasion. Figure 1 plots the average number of posts by women and men politicians on each day, before and after the invasion. The x-axis, days since invasion, ranges from 115 days before the invasion to 97 days after. The y-axis, posts per politician, is calculated by dividing the total number of posts on a given day by the number of unique politicians who posted on that day. To examine gender differences, we do this separately for women and men. The relatively stable pre-invasion pattern of posting is disrupted by the invasion, with politicians becoming significantly more active online.Footnote 52 Another striking feature is the difference in the magnitude of the change by gender. At the onset of war, the men politicians immediately start posting at a higher rate than the women politicians. And though everyone's frequency steadily decreases as conflict progresses, the gender gap remains stable throughout the rest of the study period.

FIGURE 1. Average number of posts, by gender, before and after the invasion

To systematically examine the effect of conflict onset on politicians’ engagement, we run the ITS model with Newey-West adjusted standard errors and random intercepts by politician (Table 1). The results confirm our observation from Figure 1 that conflict onset creates a gender gap in online engagement. Intercept refers to the average number of daily posts by men politicians before invasion, and the coefficient on invasion indicates the effect of war on men politicians’ posting behavior. This effect is positive and statistically significant. In substantive terms, compared to the pre-invasion period, men politicians each publish about two-and-a-half more posts per day right after the invasion. Given that their pre-invasion daily average is 0.54, this is a very sizeable effect.

Table 1. Effect of war on politicians’ engagement

Notes: Table entries are unstandardized regression coefficients from the ITS model, with Newey-West adjusted standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable, posts per politician, indicates the number of Facebook posts by each politician per day. The model also includes random intercepts by politician, and ![]() $\hat{\sigma }_{\rm id}$ indicates the estimated standard deviation of the random effects. *p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

$\hat{\sigma }_{\rm id}$ indicates the estimated standard deviation of the random effects. *p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

Before the conflict, women politicians are as engaged with the public as men, as indicated by the nonsignificant coefficient for woman. The negative and statistically significant coefficient on the interaction term (invasion × woman), in turn, suggests that the invasion affects women significantly differently than men. While their posting frequency also increases, the effect is weaker: the women publish about two more posts per day, while the men publish about two-and-a-half more posts. This supports H1, that men politicians will increase their engagement with the public significantly more than women politicians do. Importantly, it is not that women always engage less than men. Rather, the gender gap in favor of men emerges because of the conflict. In S3, we show that the results are robust to controlling for region, political offices, committee assignments, and foreign policy expertise.

H2: Role-Congruent Tone and Issues

Turning to H2, we begin by reporting the ITS results for positive sentiment (Table 2). Recall that we use four lexicons and hence obtain four positive sentiment scores per post. We employ the same ITS model as before, but change the dependent variable to the post-level sentiment score.

Table 2. Effect of war on positive sentiment

Notes: Table entries are unstandardized regression coefficients from the ITS model, with Newey-West adjusted standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is positive sentiment, with the sentiment scores from four different dictionaries given in separate columns. The model also includes random intercepts by politician, and ![]() $\hat{\sigma }_{\rm id}$ indicates the estimated standard deviation of the random effects. *p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

$\hat{\sigma }_{\rm id}$ indicates the estimated standard deviation of the random effects. *p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

As before, the coefficient of invasion indicates the change in sentiment scores for posts by men politicians after the invasion. Across all four dictionaries, we observe negative and statistically significant coefficients. That is, men politicians’ posts become significantly more negative after the invasion, adding face validity to our results. On the other hand, the positive and statistically significant coefficient on the interaction term invasion × woman shows that the increase in negative sentiment is significantly weaker among women. That is, in response to conflict, negative tone increases more among men than among women, which is in line with H2. We find similar results when using the average sentiment score per politician per day, or politician-day unit (see S4.1).

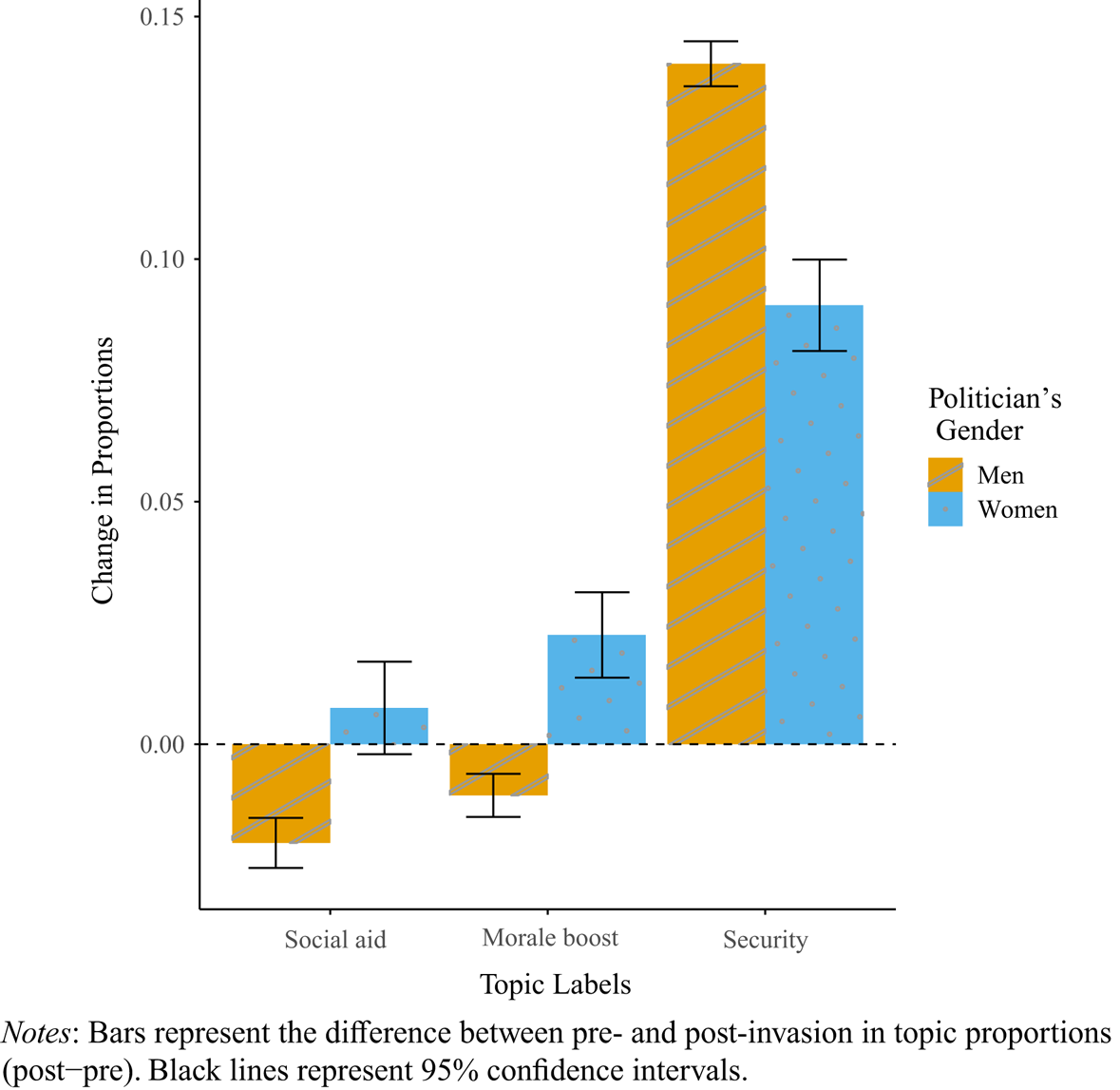

Next, we explore how conflict onset affects the issues politicians engage with. Recall that we limit our analysis to three topics with clear gendered expectations: social aid (feminine), morale boost (feminine), and security (masculine). Here, we test whether the invasion triggered changes in the proportions of posts in these topics. According to H2, on average, as conflict begins, women politicians will engage with feminine issues more than men do, and men politicians with masculine issues more than women do.Footnote 53

We start by visually inspecting the changes (in response to the invasion) in the proportion of posts under each topic by women and men politicians, as displayed in Figure 2, and observe further support for H2. In response to the invasion, women politicians discuss topics conventionally regarded as “women's issues” at higher rates than men politicians. Detecting such differences by gender is our main goal, but note that the figure also says something about the sources of these differences. For the two feminine topics, the blue (dotted) bars appear above the zero line, indicating that women politicians increased their attention to these topics after the invasion. The yellow (striped) bars, on the other hand, appear below the zero line, indicating that men's attention to these domains decreased. And on closer inspection we see that the gender difference with respect to social aid is primarily driven by men because, although women increase their attention to it, the change is not statistically significant (the 95-percent CI crosses the zero line). For morale boost, we find that men start engaging less, while women politicians engage much more. Focusing on the “masculine” topic of security, we see large and significant increases for both women and men politicians. However, the change is much larger for men than for women. This is in line with H2.Footnote 54

FIGURE 2. Changes in topic proportions before and after the invasion, by gender

We confirm these observations by fitting the ITS model with the proportion of posts belonging to each topic as the outcome variables (Table 3).Footnote 55 The invasion changes the proportions of the three topics differently for women and men: the interaction term invasion × woman is statistically significant across the three models, as expected. Furthermore, the directions of the coefficients on the interaction term all align with our expectations. After the invasion, the proportions of the “feminine” topics, social aid and morale boost, are significantly higher for women than for men politicians; and the women discuss security, a “masculine” topic, significantly less than the men. In short, across all three sets of analyses we find that war reinforces conformity with traditional gender stereotypes in politicians’ behavior.

Table 3. Effect of war on topic proportions

Notes: Table entries are unstandardized regression coefficients from the ITS model, with Newey-West adjusted standard errors in parentheses. Dependent variables are corresponding topic proportions for each politician-day unit. Models also include random intercepts by politician, and ![]() $\hat{\sigma }_{\rm id}$ indicates the estimated standard deviation of the random effects. *p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

$\hat{\sigma }_{\rm id}$ indicates the estimated standard deviation of the random effects. *p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

Extension: Citizens Prefer Men's Engagement

In addition to politicians’ own psychological need to manage terror, war can incentivize role-congruent behavior from politicians by increasing the public bias for gender stereotypes. Here, we explore this possibility by looking at how the public responds to politicians’ engagement. It is reasonable to assume that citizens respond with greater enthusiasm to the engagement of those politicians whom they favor. If our argument is correct, then in response to conflict, voters are more likely to engage with posts from men political leaders than with those from women. To measure this engagement we use the total number of user interactions on each post (“likes,” comments, “shares,” and other emoji reactions) and create a single outcome measure, reactions.Footnote 56

Figure 3 depicts the average daily reactions to politicians’ posts before and after the invasion, separated by the politician's gender.Footnote 57 Before the invasion, men and women politicians received about the same number of reactions on their posts. However, after the invasion, the men received significantly more reactions than the women. In short, the data suggest that the public engaged with posts differently after conflict onset, depending on the politician's gender.

FIGURE 3. Daily average reactions per post before and after the invasion

We used the ITS model to predict reactions (Table 4). Recall that reactions are measured at the post level. The positive and statistically significant coefficient on invasion shows a large increase in reactions to posts by men politicians after the invasion, with the average jumping from 321 to 1,092.

TABLE 4. Effect of war on public reactions

Notes: Table entries are unstandardized regression coefficients from the ITS model, with Newey-West adjusted standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is reactions: the total number of interactions given to each Facebook post. The model also includes random intercepts by politician, and ![]() $\hat{\sigma }_{\rm id}$ indicates the estimated standard deviation of the random effects. *p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

$\hat{\sigma }_{\rm id}$ indicates the estimated standard deviation of the random effects. *p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

In contrast, the conflict onset does not produce an equal increase in the number of reactions to posts by women politicians. Before, women received a similar number of reactions per post as men, as indicated by the nonsignificant coefficient on the variable woman. However, the invasion generates a massive gender gap: the statistically significant coefficient on the interaction term invasion × woman means that, at the conflict onset, a woman politician's post receives on average 491 fewer reactions than a post by a man politician. The conflict onset still increases the average number of reactions, but this increase is much smaller for women (about 280) than for men (about 771). In short, the prewar gender-blind public becomes markedly biased in favor of men in response to the invasion.Footnote 58 Thus the increase in public preference for men's leadership during war may be one of the mechanisms that further incentivizes politicians’ role-congruent behavior at conflict onset. In S5, we perform a number of additional tests and show that the results hold when (a) running the analysis separately for each type of reaction; (b) controlling for politician's region, type of political office, topic of the post, type of post, and audience size; or (c) using politician-day as the unit of analysis. We also explored the 100 most popular posts by each gender and did not notice differences in the topics or tones of these posts.

Conclusion

We provide evidence that violent conflict pushes politicians to conform more strongly with traditional gender stereotypes, so that men become more politically engaged than women, and politicians gravitate toward their respective gendered communication styles and issue spaces. Gender biases among the public also peak in response to war, which may further motivate gendered behavior by politicians. These findings contribute to our understanding of the gendered effects of conflict. While prior work has looked at how war affects representation after conflict,Footnote 59 we study it in real time as the conflict unfolds and find that the gendered effects of conflict do not develop slowly but instantaneously and profoundly, both among the public and among politicians.

One implication of our findings is that women leaders’ voices may be drowned out by their men counterparts during conflict, which is troubling. But we also find that women do engage with their publics during war, only with a different style and about different topics than men. And women politicians’ version of engagement, such as compassionately recognizing the human cost of conflict, is an important part of successful crisis management.Footnote 60

Our findings also have practical implications for how to achieve (or maintain) gender equality in wartime. Public attention could be drawn to the fact that individual preferences regarding women and men leaders are potentially biased by national insecurity. It might also help to encourage women politicians to continue engaging with the public during war. Overall, providing training and support for women politicians to navigate the challenges of conflict and raising public awareness of the importance of women's leadership in times of crisis may prevent reversals in trends toward gender equality that accompany war.

Future research could examine the behavior of women and men politicians in other contexts of violent conflict, in locations that are more or less gender equal than Ukraine, and outside of social media. The latter is particularly important because, while the social media data gave us a unique and novel opportunity to observe politicians’ behavior in real time as the conflict unfolded, they also limited the study to a specific type of engagement. Future work could also explore to what extent these initial patterns give way later to opportunities for the contestation of gender stereotypes, especially considering how immovable gender stereotypes are over long periods of time.Footnote 61 Another important direction to explore is the potential consequences of heightened role-congruent behavior in response to war. We can only speculate that such behavior by politicians could significantly affect the course of war, but in what ways and how much requires systematic analysis, the payoff of which could be significant.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Diana O'Brien, Anna Wilke, participants at the workshop on Gender Dynamics in Politics, the Workplace, and Society at Lund University, participants at the Women in Legislative Studies Conference at Brown University, and audiences at the University of Barcelona and New York University Abu Dhabi for their feedback on this project. We also thank Taishi Muraoka and our Ukrainian research assistants, hired through Upwork, for assistance with data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this research note may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KT7BWM>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this research note is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818324000080>.

Funding

This research has been generously supported through the Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy as well as the National Science Foundation (grant no. 2215008) and the Carnegie Corporation (grant no. G-23-60440).