How Ideas Spread: Whose Norms Matter? Norm Localization and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 May 2004

Abstract

Questions about norm diffusion in world politics are not simply about whether and how ideas matter, but also which and whose ideas matter. Constructivist scholarship on norms tends to focus on “hard” cases of moral transformation in which “good” global norms prevail over the “bad” local beliefs and practices. But many local beliefs are themselves part of a legitimate normative order, which conditions the acceptance of foreign norms. Going beyond an existential notion of congruence, this article proposes a dynamic explanation of norm diffusion that describes how local agents reconstruct foreign norms to ensure the norms fit with the agents' cognitive priors and identities. Congruence building thus becomes key to acceptance. Localization, not wholesale acceptance or rejection, settles most cases of normative contestation. Comparing the impact of two transnational norms on the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), this article shows that the variation in the norms' acceptance, indicated by the changes they produced in the goals and institutional apparatuses of the regional group, could be explained by the differential ability of local agents to reconstruct the norms to ensure a better fit with prior local norms, and the potential of the localized norm to enhance the appeal of some of their prior beliefs and institutions.I thank Peter Katzenstein, Jack Snyder, Chris Reus-Smit, Brian Job, Paul Evans, Iain Johnston, David Capie, Helen Nesadurai, Jeffrey Checkel, Kwa Chong Guan, Khong Yuen Foong, Anthony Milner, John Hobson, Etel Solingen, Michael Barnett, Richard Price, Martha Finnemore, and Frank Schimmelfennig for their comments on various earlier drafts of the article. This article is a revised version of a draft prepared for the American Political Science Association annual convention, San Francisco, 29 August–2 September 2001. Seminars on the article were offered at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard University, in April 2001; the Modern Asia Seminar Series at Harvard University's Asia Center, in May 2001; the Department of International Relations, Australian National University, in September 2001; and the Institute of International Relations, University of British Columbia, in April 2002. I thank these institutions for their lively seminars offering invaluable feedback. I gratefully acknowledge valuable research assistance provided by Tan Ban Seng, Deborah Lee, and Karyn Wang at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies. I am also grateful to Harvard University Asia Centre and the Kennedy School's Asia Pacific Policy Program for fellowships to facilitate my research during 2000–2001.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- © 2004 The IO Foundation and Cambridge University Press

In considering the imprint of cultural contacts, and the undoubted fact that ideas are imported along with goods, there is a need to develop a more supple language of causal connection than source and imitation, original and copy. The transfer of cultural forms produces a redistribution of imaginative energies, alters in some way a pre-existent field of force. The result is usually not so much an utterly new product as the development or evolution of a familiar matrix.1

O'Connor 1986, 7.

Why do some transnational ideas and norms find greater acceptance in a particular locale than in others? This is an important question for international relations scholars, who are challenged by Risse, Ropp, and Sikkink to pay more attention to “the causal mechanisms and processes by which … ideas spread.”2

A “second wave” of norm scholarship is responding to this challenge by focusing on how domestic political structures and agents condition normative change. As such, this scholarship complements the earlier literature focusing on transnational agents and processes shaping norm diffusion at the level of the international system.3Cortell and Davis (2000) call the domestic agency and process literature the “second wave” scholarship on norm diffusion. The “first wave” focused on the level of the international system, leading examples being Finnemore 1993 and Finnemore and Sikkink 1999. On the second wave, see especially Checkel 1998a and 2001; Gurowitz 1999; and Farrell 2001. Earlier, Risse-Kappen 1994; Klotz 1995a; Cortell and Davis 1996; and Legro 1997 had also offered powerful domestic level explanations. For a comprehensive review of the second wave literature, see Cortell and Davis 2000.

In this article, I seek to contribute to the literature on norms in two ways: first, by proposing a framework for investigating norm diffusion that stresses the agency role of norm-takers through a dynamic congruence-building process called localization, and then by using this framework to study how transnational norms have shaped regional institutions in Southeast Asia and the role of Asian regional institutions and processes—specifically the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)—in transnational norm diffusion. Empirically, this article focuses on how transnational ideas and norms4

In this article, I use ideas and norms interchangeably, recognizing that ideas can be held privately, and may or may not have behavioral implications, while norms are always collective and behavioral. Goldstein 1993.

After a period of contestation, the first proposal led ASEAN to formalize intramural security dialogues, adopt a more inclusive posture toward outside powers' role in regional order, and anchor a new security institution for the wider Asia Pacific region. In contrast, the attempt to dilute the noninterference norm on the basis of the flexible engagement idea failed, producing only some weak policy instruments.

Why this variation? Central to the norm dynamic I present is the contestation between emerging transnational norms and preexisting regional normative and social orders. But unlike other scholars who have addressed the question of resistance and agency of domestic actors, I place particular emphasis on a dynamic process called localization. Instead of just assessing the existential fit between domestic and outside identity norms and institutions, and explaining strictly dichotomous outcomes of acceptance or rejection, localization describes a complex process and outcome by which norm-takers build congruence between transnational norms (including norms previously institutionalized in a region) and local beliefs and practices.5

“Norm-maker” and “norm-taker” are from Checkel 1998a, 2.

The article's focus on ASEAN and Asian regionalism is important. Founded in 1967, ASEAN was arguably the most successful regional institution outside Europe during the Cold War period.6

ASEAN's founding members, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, and Singapore, were joined by Brunei (1984), Vietnam (1995), Laos and Burma (1997), and Cambodia (1999).

Kahler 1994, 22. See also Kahler 2000, 551.

It is also necessary to stress at the outset that this article investigates norm diffusion, rather than norm displacement. Constructivist norm scholars have often sought out cases involving fundamental normative change, thereby avoiding “the dog who didn't bark.”9

Checkel 1998b, 4.

Hopf 1998, 180.

Two Perspectives on Norm Diffusion

The first wave scholarship on normative change speaks to a moral cosmopolitanism. It has three main features. First, the norms that are being propagated are “cosmopolitan,” or “universal” norms, such as the campaign against land mines, ban on chemical weapons, protection of whales, struggle against racism, intervention against genocide, and promotion of human rights, and so on.11

For examples, see Sikkink 1993; Peterson 1992, Litfin 1994; and Klotz 1995a and 1995b.

See Nadelmann 1990, 483; Risse, Ropp, and Sikkink 1999; and Keck and Sikkink 1998.

Nadelmann 1990, 481.

The moral cosmopolitanism perspective has contributed to two unfortunate tendencies. First, by assigning causal primacy to “international prescriptions,” it ignores the expansive appeal of “norms that are deeply rooted in other types of social entities—regional, national, and subnational groups.”14

Legro 1997, 32.

See Finnemore 1996; and Finnemore and Sikkink 1999, 267.

Second, moral cosmopolitanists view norm diffusion as teaching by transnational agents, thereby downplaying the agency role of local actors.17

See Finnemore 1993; and Barnett and Finnemore 1999.

On the distinction between regulative, constitutive and prescriptive norms, see Finnemore and Sikkink 1999, 251.

A second perspective on norm diffusion looks beyond international prescriptions and stresses the role of domestic political, organizational, and cultural variables in conditioning the reception of new global norms.19

See Risse-Kappen 1994; Cortell and Davis 1996; Legro 1997; and Checkel 1998a and 2001.

See Price 1998; and Florini 1996.

Legro 1997, 33, 36.

Checkel 1998a, 4.

Ibid., 6.

While capturing the role of local agents in norm diffusion, these perspectives, which remain confined to the domestic arena (as opposed to a regional context involving two or more states that is the focus of this article), can be unduly static, describing an existential match—how “historically constructed domestic identity norms create barriers to agent learning from systemic norms”24

Checkel 1998a. Legro's more recent work proposes a more dynamic effect of ideational structures stemming from the undesirable consequences of existing ideas and the availability of viable replacement ideas. See Legro 2000.

Ikenberry 1988, 242.

Two other concepts—framing and grafting—offer a more dynamic view of congruence. Framing is necessary because “the linkages between existing norms and emergent norms are not often obvious and must be actively constructed by proponents of new norms.”26

Through framing, norm advocates highlight and “create” issues “by using language that names, interprets, and dramatizes them.” 27Ibid.

See Klotz 1995a; and Klotz 1995b.

“Grafting” (or “incremental norm transplantation” to use Farrell's phrase, to be distinguished from “radical transplantation” or “norm displacement”29

) is a tactic norm entrepreneurs employ to institutionalize a new norm by associating it with a preexisting norm in the same issue area, which makes a similar prohibition or injunction. Price has shown how the campaign to develop a norm against chemical weapons was helped by invoking the prior norm against poison.30 But grafting and framing are largely acts of reinterpretation or representation rather than reconstruction. More important, neither is necessarily a local act. Outsiders usually perform them.31See, for example, the idea of norm transplantation in Farrell 2001.

Localization goes further. It may start with a reinterpretation and re-representation of the outside norm, including framing and grafting, but may extend into more complex processes of reconstitution to make an outside norm congruent with a preexisting local normative order. It is also a process in which the role of local actors is more crucial than that of outside actors. Instead of treating framing, grafting, and other adaptive processes as distinct and unrelated phenomena, I use localization to bring them together under a single conceptual framework and stress the agency role of local actors in performing them.

The Dynamics of Norm Localization

In developing the concept of localization, I draw on Southeast Asian historiographical concepts that claim that Southeast Asian societies were not passive recipients of foreign (Indian and Chinese) cultural and political ideas, but active borrowers and localizers.32

See Wolters 1982 and 1999. For a summary of the literature, see Mabbett 1977a and 1977b.

In the following sections, I draw from this literature to develop the idea of localization in three important areas: what is localization; why localization takes place and under what conditions is it likely to occur; and what kind of change it produces.

What Is Localization?

To localize something is to “invest [it] with the characteristics of a particular place.”33

I define localization as the active construction (through discourse, framing, grafting, and cultural selection) of foreign ideas by local actors, which results in the former developing significant congruence with local beliefs and practices. Wolters, a leading proponent of localization in Southeast Asian studies, calls this a “local statement … into which foreign elements have retreated.”34Wolters 1999, 57.

The concept of localization extrapolated from Southeast Asian historiography offers three important ideas about how and why ideas travel and produce change across cultures and regions.35

While Wolters developed his concept of localization to study the diffusion of Indian and Chinese ideas into classical Southeast Asia, the discourse on localization in Southeast Asian social science literature extends well into the contemporary period. On the localization of Chinese ideas in Southeast Asia, see Wolters 1982, 46–47; Osborne 1979, 13–14. On the Southeast Asian characteristics of Islamic ideas, see Anderson 1990, 68.

“Southeast Asian rulers, in an attempt at legitimizing their interest … and organizing and domesticating their states and subjects … called Indian civilization to the east.” Van Leur 1955, 98. See also Mabbett 1977b, 143–44. The earlier explanations focusing on conquest and commerce are also known as: (1) the ksatriya (Sanskrit for warrior) theory—which saw the transmission of Indian ideas as the result of direct Indian conquest and colonization of large parts of Southeast Asia; and (2) the vaisya (merchant) theory—which emphasized the role of Indian traders with their extensive commercial interactions with Southeast Asia, who brought with them not just goods, but also Indian cultural artifacts and political ideas. Van Leur's thesis has since been challenged by others for having over-emphasized local initiative, but it marked a decisive turning point towards an “autonomous” historiography of Southeast Asia.

A second insight of the Southeast Asian literature concerns the idea-recipient's adjustments to the shape and content (or both) of foreign ideas to make it more congruent with the recipient's prior beliefs and practices. This might start with an act of cultural selection: borrowing only those ideas that are, or can be made, congruent with local beliefs and that may enhance the prestige of the borrower. As McCloud puts it, “Southeast Asians borrowed only those Indian and Chinese cultural traits that complemented and could be adapted to the indigenous system.”37

McCloud 1995, 69.

An important example can be found in M. B. Hooker's analysis of how Indian legal-moral frameworks were adjusted to fit indigenous beliefs and practices in Indonesia. Hooker 1978, 35–36. While localization modifies the foreign idea at the receiving end, it does not necessarily produce a feedback on outside norm entrepreneur's preferences and identity. In other words, localization need not be a two-way process. But the content of the foreign norm does change in the context of the recipient's milieu; the persuader's ideas are reformulated in the local context.

Such adjustments were motivated by two main realities. First, the idea recipient's chief goal was to strengthen, not replace, existing institutions, such as the kingship, with the infusion of new pathways of legitimation. Hence, wholesale borrowing of foreign ideas that might supplant existing institutions could not be undertaken. Second, cultural predilections, and deeply ingrained beliefs in the importance of existing institutions sanctified by popular beliefs (such as myth of origin) and nurtured through rituals and practices, could not be easily sacrificed without incurring social and political costs. Thus, there could be “rational” exclusion of certain elements of new ideas that might harm the existing social order or increase the risk of social and political instability. In the next section, I will discuss the implications of these considerations in explaining the motivation of norm diffusion.

A third relevant insight of the localization idea in Southeast Asian historiography concerns its effect. Far from extinguishing local beliefs and practices, foreign ideas may help to enhance the profile and prestige of local actors and beliefs. Wolters claims that while borrowing Hindu ideas about legitimacy and authority, Southeast Asian rulers did not abandon their prior political beliefs and practices. Instead, the latter were “amplified,” meaning that “ancient and persisting indigenous beliefs [were brought] into sharper focus.” 39

Wolters 1982, 9.

Kirsch 1977, 263.

Why Localize?

Why do norm-takers want to localize international norms and what are the conditions that may affect the likelihood of localization because of their actions? One may start to address this question by looking at several generic forces that create the demand for new norms in the first place. First, a major security or economic crisis (war or depression) can lead to norm borrowing by calling into question “existing rules of the game.”41

Ikenberry 1988, 234.

Klotz 1995a, 23.

The key question for this article of course is why the demand for new norms leads to their localization, in which some key characteristics of the preexisting normative order are retained rather than displaced wholesale. From a rationalist perspective, localization is simply easier, especially when prior norms are embedded in strong local institutions. Institutionalist scholars hold that it is “easier to maintain and adapt existing institutions than to create new ones.”46

Nye and Keohane 1993, 19. See also Aggarwal 1998, 53.

According to their study, the anti–foot binding campaign succeeded because it added moral force to the Chinese national reform movement that was already seeking improvements in women's status as a “necessary part of their program for national self-strengthening.” But attempts to ban female circumcision in Kenya failed because it conflicted with the existing nationalist agenda that saw female circumcision as integral to local culture and identity. Keck and Sikkink 1998, 62.

But localization is not simply a pragmatic response to the demand for new norms. The prospect for localization also depends on its positive impact on the legitimacy and authority of key norm-takers, the strength of prior local norms, the credibility and prestige of local agents, indigenous cultural traits and traditions, and the scope for grafting and pruning presented by foreign norms.

First, localization is likely if the norm-takers come to believe that new outside norms—which may be initially feared and resisted simply because of their alien quality—could be used to enhance the legitimacy and authority of their extant institutions and practices, but without fundamentally altering their existing social identity. Cortell and Davis show that actors borrow international rules to “justify their own actions and call into question the legitimacy of others.”48

Cortell and Davis 1996, 453.

Wolters 1982, 102.

A second factor favoring localization is the strength of prior local norms. Some local norms are foundational to a group. They may derive from deeply ingrained cultural beliefs and practices or from international legal norms that had, at an earlier stage, been borrowed and enshrined in the constitutional documents of a group. In either case the norms have already become integral to the local group's identity, in the sense that “they constitute actor identities and interests and not simply regulate behavior.”50

See Checkel 1998b, 325, 328.

A third condition favoring localization is the availability of credible local actors (“insider proponents”) with sufficient discursive influence to match or outperform outside norm entrepreneurs operating at the global level. The credibility of local agents depends on their social context and standing. Local norm entrepreneurs are likely to be more credible if they are seen by their target audience as upholders of local values and identity and not simply “agents” of outside forces or actors and whether they are part of a local epistemic community that could claim a record of success in prior normative debates.

Constructivist scholarship on norm diffusion often privileges “transnational moral entrepreneurs.” It defines their task as being to: “mobilize popular opinion and political support both within their host country and abroad,” “stimulate and assist in the creation of likeminded organizations in other countries,” and “play a significant role in elevating their objectives beyond its identification with the national interests of their government.”51

Nadelmann 1990, 482. Emphasis added.

Ibid.

Such local and insider proponents are usually physically present within the region and can be either from the government, or part of the wider local policymaking elite with reasonably direct access to policymakers, or part of an active civil society group. The theory of entrepreneurship acknowledges that there has been inadequate attention to the “adaptive role of entrepreneurs as they adjust to their environment” and “to their learning experience.” Some of this learning experience may relate to the attitude of consumers, or norm-takers. Deakins 1999, 23. See also Drucker 1999; and Burch 1986.

While the initiative to spread transnational norms can be undertaken either by local or foreign entrepreneurs, diffusion strategies that accommodate local sensitivity are more likely to succeed than those who seek to supplant the latter. Hence, outsider proponents are more likely to advance their cause if they act through local agents, rather than going independently at it. An example of the insider proponent's role can be found in Wiseman's analysis of the diffusion of the nonprovocative defense norm to the Soviet Union. Wiseman shows how local supporters of this norm within the Soviet defense community facilitated its acceptance “by resurrecting a defensive ‘tradition’ in Soviet history,” thereby reassuring “domestic critics that they were operating historically within the Soviet paradigm and to avoid the impression that they were simply borrowing Western ideas.”54

Wiseman 2002, 104.

Fourth, it is the norm-takers' sense of identity that facilitates localization, especially if they possess a well-developed sense of being unique in terms of their values and interactions. For example, Ball has identified the existence of such a sense of uniqueness affecting regional interactions.55

The principal dimensions of Asian strategic culture, Ball argues, “includes styles of policy making which feature informality of structures and modalities, form and process as much as substance and outcome, consensus rather than majority rule, and pragmatism rather than idealism.” Ball 1993, 46.

See Nischalke 2000; and Haacke 2003.

Osborne 1990, 5–6.

Describing this dynamics of ideational contestation involving ideas such as democracy and socialism, Anderson writes: “In any such cross-cultural confrontation, the inevitable thrust is to ‘appropriate’ the foreign concept and try to anchor it safely to given or traditional ways of thinking and modes of behavior. Depending on the conceptions of the elite and its determination, either the imported ideas and modalities or the traditional ones assume general ascendancy: in most large and non-communist societies it is almost invariable that at least in the short run, the traditional modalities tend to prevail.” Anderson 1966, 113.

McCloud 1995, 338.

Although this article presents localization as a dynamic process, the existential compatibility between foreign and local norms must not be ignored as another catalyst. The prior existence of a local norm in similar issue areas as that of a new external norm and which makes similar behavioral claims makes it easier for local actors to introduce the latter. Moreover, the external norm must lend itself to some pruning, or adjustments that make it compatible with local beliefs and practices, without compromising its core attributes. Hence, the relative scope for grafting and pruning presented by a new foreign norm contributes to the norm-taker's interest to localize and is critical to its success.

Drawing on the immediate discussion of the motivating forces of and conditions favoring localization and the previous discussion of the three aspects of localization in Southeast Asian historiography, Table 1 outlines a trajectory of localization, specifying the conditions of progress.

The trajectory of localization and conditions for progress

What Kind of Change?

In some respects, localization is similar to behavior that scholars have described as adaptation.60

But adaptation is a generic term that can subsume all kinds of behaviors and outcomes. Localization has more specific features. As Wolters points out, adaptation “shirk[s] the crucial question of where, how and why foreign elements began to fit into a local culture” and obscures “the initiative of local elements responsible for the process and the end product.”61Wolters 1999, 56.

Ibid.

Moreover, in Southeast Asian historiography, localization is conceived as a long-term and evolutionary assimilation of foreign ideas, while some forms of adaptation in the rationalist international relations literature are seen as “short run policy of accommodation.”63

Johnston 1996, 28.

Localization does not extinguish the cognitive prior of the norm-takers but leads to its mutual inflection with external norms. In constructivist perspectives on socialization, norm diffusion is viewed as the result of adaptive behavior in which local practices are made consistent with an external idea. Localization, by contrast, describes a process in which external ideas are simultaneously adapted to meet local practices.64

I am grateful to an anonymous referee for International Organization for suggesting this formulation to distinguish adaptation from localization.

This may be called “constitutive localization” but the outcome should not be confused with what constructivists take as the “constitutive impact” of norms, which implies a fundamental transformation of the recipient's prior normative preferences and behavior. From this article's perspective, such impact would amount to norm displacement.

Localization is progressive, not regressive or static. It reshapes both existing beliefs and practices and foreign ideas in their local context. Localization is an evolutionary or “everyday” form of progressive norm diffusion. Wolters and Kirsch use the Parsonian term “upgrading” to describe the political and civilizational advancement of Southeast Asian societies from the infusion of foreign ideas,66

while Bosch describes the outcome of localization as a situation in which “the foreign culture gradually blend[s] with the ancient native one so as to form a novel, harmonious entity, giving birth eventually to a higher type of civilization than that of the native community in its original state.”67Bosch 1961, 3.

In Southeast Asian historiography, localization of Indian ideas produced two kinds of change: expansion of a ruler's authority to new functional and geographic areas and the creation of new institutions and regulatory mechanisms that in turn legitimized and operationalized such expansion.68

Wolters found the chief effect of localization being in the extension of the authority and legitimacy of the native chiefs (the “man of prowess”) from the cultural and religious to the political domain. Wolters 1982, 52. Van Leur described the effects of localization as being the “legitimation of dynastic interests and the domestication of subjects, and … the organization of the ruler's territory into a state.” Van Leur 1955, 104.

Wheatley 1982, 27.

Drawing on the institutionalist literature, I focus on two generic types of institutional change: (1) task (functional scope)70

See Aggarwal 1998, 32, 60; and Keohane and Hoffmann 1993, 386.

See, for example, Haas's study of the Mediterranean cleanup. Haas 1990.

Aggarwal 1998, 42, 44.

Localization is indicated when an extant institution responds to a foreign idea by functional or membership expansion and creates new policy instruments to pursue its new tasks or goals without supplanting its original goals and institutional arrangements (defined as “organizational characteristics of groups and … the rules and norms that guide the relationships between actors.”76

Ikenberry 1988, 223.

Hall and Taylor 1998, 19.

Aggarwal argues that institutional change can lead either to modifying existing institutions or creating new ones. If new ones are created, then they could take two forms: nested institutions and parallel institutions. Aggarwal 1998, 42, 44.

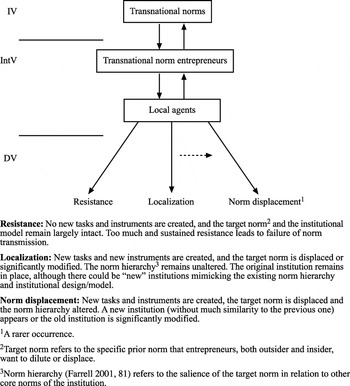

Figure 1 illustrates three main forms of local responses to transnational norms. In localization, institutional outcomes such as task expansion and procedural innovation result from the acceptance of a locally modified foreign norm. While some original norms and practices may be significantly modified, the overall norm hierarchy and the institutional model remain in place. This means a locally modified foreign norm can enter the norm hierarchy of an extant institution without necessarily taking precedence over its other prior norms.

Local responses to transnational norms

But over the long term, localization may produce an incremental shift toward fundamental change or norm displacement. After local actors have developed greater familiarity and experience with the new ideas, functions and instruments, resistance to new norms may weaken, opening the door to fundamental changes to the norm hierarchy. This comes at the very long end of localization, which occurs and defines normative interactions in the interim. Localization provides an initial response to new norms pending norm displacement, which may or may not occur. But at least localization gives such change a decent chance.

In the following sections, I compare two proposals about reshaping ASEAN in the 1990s to explain an important puzzle: Why did proposals underpinned by a reframed global norm (humanitarian intervention) that was more convergent with the policies of powerful actors, and that was conceived as an answer to the severe economic crisis facing the region, fare poorly with ASEAN compared to proposals underpinned by a reframed European norm (common security), which had been initially rejected by the powerful actors (especially the United States)? The answer, I argue, lies in the relative scope of localization for the two norms. Drawing on a range of secondary and primary sources, I employ a process-tracing approach to illustrate how the process of localization shaped the progress of the outside norm at different junctures and look for evidence of localization in terms of the dependent variable of institutional change discussed above.

Case Studies

Case 1: ASEAN and Cooperative Security

Toward the end of the Cold War (1986–90), leaders from the Soviet Union, Canada, and Australia advanced proposals toward multilateral security cooperation in the Asia Pacific. These proposals shared two common features.79

See Clark 1990a, 1990b; Evans 1990; and Evans and Grant 1995.

There is considerable literature attesting to how the European common security norm affected security debates in Asia. See Clements 1989; Wiseman 1992; and Dewitt 1994.

The common security idea was articulated in the 1982 report of the Independent Commission on Disarmament and Security Issues, chaired by the late Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme.81

Although not directly espoused by the CSCE, the latter did represent, in Asian policy circles at least, the closest institutionalization of the common security norm.82Common security was not formally a CSCE norm, although that is how it is widely perceived in Asian debates.

The CBM regime of the CSCE included the presence of observers from both sides at large military exercises, increased transparency and information sharing. On the CSCE's CBM agenda, see Krause 2003.

The CSCE successfully incorporated human rights issues into the regional confidence-building agenda, thereby setting norms that would regulate the internal as well as external political behavior of states. Zelikow 1992, 26.

Proposals for common security approaches in the Asia Pacific date back to 1986, when the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev proposed a “Pacific Ocean conference along the Helsinki [CSCE] conference,” to be attended by all countries “gravitating” toward the Pacific Ocean to discuss peace and security in the region.85

Acharya 1993, 59.

International Herald Tribune, 27 July 1990, 6.

Ibid. Evans was clearly inspired by the Palme Commission Report and by the common security idea. Interview by author with Geoff Wiseman, Foreign Minister Evans's private secretary in 1990, 24 March 2002, New Orleans, LA.

Although these proposals called for an Asia Pacific institution and were not specifically directed at ASEAN, the latter, as the most successful Asian grouping, became an important site for debating them. In its initial reaction, ASEAN feared that these proposals could undermine its existing norms and practices. At stake were three key practices. One was ASEAN's avoidance of military-security cooperation. This itself was because of fears of provoking its Cold War adversaries, Vietnam and China, which had denounced ASEAN as a new front for the now-defunct American-backed Southeast Asian Treaty Organization. ASEAN also felt that attention to military security issues would be divisive and undermine economic and political cooperation.

A second ASEAN norm at risk was the Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality (ZOPFAN) framework. Articulated in 1972, ZOPFAN was geared to minimizing the role of external powers in regional affairs. ZOPFAN was thus an “exclusionary” framework. A common security institution, in contrast, would bring together ASEAN and the so-called outside powers within a single security framework, allowing them a legitimate role in regional security. ZOPFAN had remained an official goal of ASEAN, although ASEAN members were already divided over it. Singapore and Thailand favored closer defense links with, rather than the exclusion of, the United States. ZOPFAN's post–Cold War relevance had also been questioned.89

For details, see Acharya 1993 and 2001, 54–56.

A third ASEAN normative tradition at stake was the “ASEAN Way,” a short-hand for organizational minimalism and preference for informal nonlegalistic approaches to cooperation.90

Acharya 1997a and 2001.

ASEAN's discomfort with the Soviet, Canadian, and Australian proposals was aggravated by the fact they all came from outsider proponents. Accepting the proposals could lead ASEAN to “lose its identity.”91

Excerpts from Lee Kuan Yew's interview with The Australian, published in The Straits Times, 16 September 1988.

Interview by author with Ali Alatas, 4 June 2002, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

It was “sensitivity” to such ASEAN reaction that led Australian Foreign Minister Evans to modify his proposal.94

Interview by author with Geoff Wiseman, 24 March 2002, New Orleans, La.

Evans 1990, 429.

The ASEAN-ISIS brought together think tanks from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines and Thailand with the goal being to “encourage cooperation and coordination of activities among policy-oriented ASEAN scholars and analysts, and to promote policy-oriented studies of, and exchanges of information and viewpoints on, various strategic and international issues affecting Southeast Asia and ASEAN's peace, security and well-being.” ASEAN-ISIS 1991, 1.

See Dewitt 1994.

Though formally established in 1988, ASEAN-ISIS had been in existence as an informal network for over a decade, organizing “Second Track” meetings that brought together Asian and Western scholars and policymakers interested in multilateral security. A 1991 ASEAN-ISIS document, “A Time for Initiative,” urged dialogues and measures that would result in a multilateral security institution.98

See ASEAN-ISIS 1991, 2–3; Lau 1991; and Razak 1992.

ASEAN-ISIS pushed for cooperative security because it realized that the end of the Cold War and the settlement of the Cambodia conflict (which had hitherto preoccupied ASEAN and contributed to its success) required ASEAN to develop a new focus.99

Interview by author with Jusuf Wanandi of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies and a founding leader of ASEAN-ISIS, 4 June 2002, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

The Business Times (Singapore), 25 July 1994, 3.

Interview by author with Ali Alatas, 4 June 2002, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

An equally important factor behind ASEAN's more receptive attitude toward cooperative security was its recognition of some important common ground between this norm and the existing ASEAN principles and processes. The rejection of deterrence fitted well into ASEAN's existing policy of not organizing itself into a regional collective defense system. The idea that security should be pursued multilaterally resonated well with Indonesia's earlier effort to develop a shared understanding of security in ASEAN through a doctrine of “regional resilience.”102

Acharya 1991. In the 1970s, Indonesia organized a series of seminars to disseminate the concept of national and regional “resilience,” which created the basis for a multilateral security approach. Interview by author with Kwa Chong Guan, Council Member of the Singapore Institute of International Affairs, 21 May 2003, Singapore.

At its Singapore summit in January 1992, ASEAN agreed to “use established fora to promote external security dialogues on enhancing security in the region as well as intra-ASEAN dialogues on ASEAN security cooperation.”103

ASEAN 1992, 2.

This initiative drew on recent ASEAN-ISIS proposals, with Yokio Satoh, who headed the policy-planning bureau of the Japanese Foreign Ministry, providing the link. Interview by author with Yukio Satoh, 1 June 2002, Singapore.

Acharya 2001, 172–73.

As the first Asia Pacific institution dedicated to security issues, the ARF represents a significant expansion of ASEAN's security agenda. It is the most inclusive regional institution: counting among its members all the major powers (including the EU) of the contemporary international system. Its creation marked a significant break with ASEAN's ZOPFAN norm.106

Leifer 1996, 19.

The Business Times (Singapore), 25 July 1994, 3.

The ARF's policy instruments have been characterized as “evolutionary developments from extant regional structures rather than the importation of Western modalities or the creation of new structures.”109

Ball 1997, 16–17.

ASEAN 1995, Annex A and B, 8–11.

To sum up, the cooperative security norm contributed to two institutional outcomes: new tasks (security cooperation) for an existing regional institution (ASEAN) that displaced a long-standing norm (ZOPFAN), and the creation of a new institution, the ARF, closely modeled on ASEAN. For the first time in history, Southeast Asia and the Asia Pacific acquired a permanent regional security organization.

The diffusion of the cooperative security norm was also indicated in the participation of China and the United States in the ARF. Neither was at first supportive of multilateral security. China saw in it the danger that its neighbors could “gang up” against its territorial claims in the region. But its attitude changed in the mid-1990s. To quote a Chinese analyst, China was “learning a new form of cooperation, not across a line [in an] adversarial style, but [in a] cooperative style.” This, he added, would change Chinese strategic behavior in the long-term. Chinese policymakers consistently stressed cooperative security as a more preferable approach to regional order than balance of power approaches.111

This and other statements on China's growing receptivity to cooperative security could be found in a report prepared by the author after interviews conducted between 1997 and 1999 with analysts and policymakers at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Beijing; China Institute of International Studies (CIIS); China Institute of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR); China Centre for International Studies (CCIS); Institute of Asia Pacific Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CAAS); Institute for Strategic Studies, National Defense University, the People's Liberation Army. See Acharya 1999. See also Johnston 2003.

During initial debates about cooperative security, Richard Solomon, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs in the George Bush (senior) administration, argued that the region's problems could not be solved “by working through a large, unwieldy, and ill-defined region-wide collective security forum.”112

The Bush administration feared that an Asian multilateral institution would undermine America's bilateral security alliances in the region.113For initial U.S. reservations about multilateralism, see Solomon 1990.

Cited in Capie 2002, 159.

Boyce 1999, 1.

Case 2: ASEAN and Flexible Engagement

The establishment of the ARF in 1994 boosted ASEAN's international prestige. But the glory was short-lived. ASEAN suffered a major setback in the wake of the Asian economic crisis that began in mid-1997. The crisis revealed the vulnerability of ASEAN to global economic trends. The failure of ASEAN to respond to the crisis with a united front drew considerable criticism. A key fallout was proposals for reforming ASEAN to make it more responsive to transnational challenges. Leading the reformist camp was Surin Pitsuwan, who became the foreign minister of a new Thai government in 1997. At a time when ASEAN's critics were blaming the currency crisis on its lack of a financial surveillance system,117

“ASEAN's Failure: The Limits of Politeness,” The Economist, 28 February 1998, 43.

“Thailand Challenges ASEAN ‘Non-Interference’ Policy,” Agence France Presse, 13 June 1998.

All the ASEAN members have the responsibility of upholding the principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of one another. But this commitment cannot and should not be absolute. It must be subjected to reality tests and accordingly it must be flexible. The reality is that, as the region becomes more interdependent, the dividing line between domestic affairs on the one hand and external or transnational issues on the other is less clear. Many “domestic” affairs have obvious external or transnational dimensions, adversely affecting neighbors, the region and the region's relations with others. In such cases, the affected countries should be able to express their opinions and concerns in an open, frank and constructive manner, which is not, and should not be, considered “interference” in fellow-members' domestic affairs.119

Pitsuwan's ideas, known as “Flexible Engagement,” became a focal point of debate in Southeast Asian regional dialogues. Although ostensibly geared to an economic crisis, Pitsuwan's real aim was to promote greater political openness and transparency in ASEAN, both at domestic and regional levels. Among the ideational underpinnings of flexible engagement were emerging post-Westphalian concepts of collective action, including the norm of humanitarian intervention (HI) and the advocacy of human rights and democratization by the international community.120

Several discussions by the author with Pitsuwan confirmed this influence. Pitsuwan became a member of the Commission on Human Security and an adviser to the International Commission on State Sovereignty and Humanitarian Intervention, which was tasked to improve the legitimacy and effectiveness of humanitarian intervention. Interview by author with Surin Pitsuwan, 7 September 2001, Singapore; interview by author with Pitsuwan, 10 May 2002, Bangkok, Thailand.

In Southeast Asia, the HI norm had attracted no insider advocacy, only suspicion and rejection. Malaysia's Foreign Minister Syed Hamid Albar found it “disquietening (sic).”121

He urged the region “to be wary all the time of new concepts and new philosophies that will compromise sovereignty in the name of humanitarian intervention.”122“Malaysia Opposes UN Probe of East Timor Atrocities,” Agence France Presse, 7 October 1999.

Neither had the norm received backing from the local epistemic community. ASEAN-ISIS was too divided over this norm to play an advocacy role. Support for a diluted form of regional intervention came only from two individual leaders. Before Pitsuwan, Anwar Ibrahim, then Deputy Prime Minister of Malaysia, had proposed the idea of “constructive intervention” as a compromise between HI and “constructive engagement.” In July 1997, he urged ASEAN to assist its weaker members in avoiding internal collapse.123

Acharya 1997b. The paper was presented at a workshop organized by Ibrahim's think tank, Institute of Policy Studies.

“ASEAN Turns to ‘Constructive Intervention’,” Asian Wall Street Journal, 30 September 1997, 10.

Anwar Ibrahim, “Crisis Prevention,” Newsweek (International), 21 July 1997, 29.

Because of opposition from fellow ASEAN members, Ibrahim's proposal was never officially tabled. Against this backdrop, Pitsuwan, who was clearly influenced by Ibrahim's idea,126

When Pitsuwan first presented his ideas, he used the term “constructive intervention.” But Thai foreign ministry officials felt this sounded “too radical” and coined the less intrusive term “flexible engagement.” Capie and Evans 2002.

Interview by author with Surin Pitsuwan, 30 January 2001, Bangkok, Thailand.

See “Thailand Calls for ‘Flexible Engagement’ in ASEAN,” Japan Economic Newswire, 26 June 1998; and Pitsuwan 1998a.

Though diluted, flexible engagement nonetheless was the most significant challenge to ASEAN's noninterference norm. Regional crisis and domestic change were important catalysts behind Pitsuwan's initiative. Pitsuwan viewed the former as “a clear and present danger” to ASEAN.130

His new Thai government was keen to prove its democratic credentials to the international community by distancing itself from ASEAN's noninterference-based support for Burma's repressive regime, and the lack of transparency and accountability in ASEAN member states generally.131But Pitsuwan's intrusive regionalism was not backed by any prior regional tradition. ASEAN was founded as a grouping of illiberal regimes with no record of collectively promoting human rights and democratic governance. The antiapartheid movement in South Africa had succeeded partly because campaigners could link their struggle with the prior norm against racism. The campaign by human rights activists against Burma failed because advocacy of human rights and democratic governance had no place in ASEAN, which did not specify a democratic political system as a criterion for membership.

Moreover, while ASEAN's ZOPFAN norm had already been discredited internally, noninterference was still enjoying a robust legitimacy. As Singapore's Foreign Minister S. Jayakumar put it, “ASEAN countries' consistent adherence to this principle of non-interference” had been “the key reason why no military conflict ha[d] broken out between any two member countries since the founding of ASEAN.”132

The Straits Times, 23 July 1998, 30.

Pitsuwan's critics within ASEAN argued that ASEAN's existing mechanisms and processes were adequate for dealing with the new challenges. Malaysia's then Foreign Minister (and now Prime Minister) Abdullah Badawi claimed that ASEAN members had always cooperated in solving mutual problems, which sometimes required commenting on each other's affairs, but they had done so “quietly, befitting a community of friends bonded in cooperation and ever mindful of the fact that fractious relations undermine the capacity of ASEAN to work together on issues critical to our collective well-being.”133

Flexible engagement offered no opportunity for enhancing ASEAN's appeal within the larger Asia Pacific region. Instead, ASEAN members feared that such a policy would provoke vigorous Chinese opposition and undermine the ARF, the very brainchild of ASEAN. Indeed, the survival of ASEAN would be at risk. Leading the opposition from founding members Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, Singapore's Jayakumar argued that abandoning noninterference would be “the surest and quickest way to ruin … ASEAN.”134

The Straits Times, 23 July 1998, 30.

Success in localization depends on the insider proponents being seen as upholders of local values and identity. But their ASEAN peers saw both Ibrahim and Pitsuwan as “agents” of the West, promoting the latter's agenda of human rights promotion and democratic assistance. Though local in persona, they were insufficiently local in their inspiration and motivation.

Flexible engagement failed to produce any meaningful institutional change in ASEAN.135

See The Straits Times, 24 July 1998, 3; and The Straits Times, 26 July 1998, 15.

See “ASEAN Ministers Adopt Policy of ‘Enhanced Interaction’,” Asia Pulse, 27 July 1998; Interview by author with Surin Pitsuwan, 10 May 2002, Bangkok, Thailand; and interview by author with Ali Alatas, 4 June 2002, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Interview by author with Surin Pitsuwan, 10 May 2002, Bangkok, Thailand.

See Funston 1998; Nischalke 2000; and Haacke 2003. At the end of the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting in Manila on 25 July 1998, which saw the most intense debate over whether ASEAN should shift from noninterference to “flexible engagement,” Singapore's S. Jayakumar, the incoming Chairman of ASEAN's Standing Committee, flatly noted that the meeting “began amidst some confusion and speculation as to whether there would be changes to ASEAN's fundamental principles. These controversies have been laid to rest…. The basic principles of non-intervention and decision making by consensus would remain the cornerstones of ASEAN.” Jayakumar 1998.

ASEAN did create two new policy instruments as part of its “enhanced interaction” agenda. The first was an ASEAN Surveillance Process (ASP) created in 1998 to monitor regional economic developments, provide early warning of macroeconomic instability, and encourage collective action to prevent an economic crisis.140

Interview by author with Termsak Chalermpalanupap, Special Assistant to the Secretary General, ASEAN, 16 January 2001, Bangkok, Thailand.

ASEAN 2000. The debate over the noninterference norm in ASEAN is unlikely to fade, however. In 2003, ASEAN foreign ministers expressed concern over the domestic situation in Burma and deepened cooperation against terrorism and the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). A dilution of noninterference is possible if such external crises bring to the fore new insider proponents and more effective framing and grafting discourses. But any such shift from noninterference in ASEAN will be gradual and path dependent.

Comparison

The localization of cooperative security had three main effects on ASEAN: (1) its acceptance of security dialogues and cooperation as a formal task for ASEAN itself; (2) the displacement of the inward-looking ZOPFAN norm in favor of a more inclusive approach, which allowed ASEAN to play the role of midwife to the birth of a new Asia-wide security institution; and (3) the adoption by the new security institution (ARF) of new policy instruments, including CBMs, based on the ASEAN model. It is fair to say that the target norm of ZOPFAN was not just modified, but displaced. In contrast, the flexible engagement proposal underpinned by the HI norm did not produce any meaningful institutional change in ASEAN. ASEAN continues to exclude human rights and democratic assistance tasks and the target norm, noninterference, remains firmly in place. While some new policy instruments were created, these remain weak and limited.

The variation can be explained in terms of the localization framework. Both norms challenged cognitive priors in ASEAN: advocates of cooperative security targeted the ZOPFAN concept and those of flexible engagement targeted its noninterference doctrine. But noninterference was still enjoying a robust legitimacy, while the ZOPFAN idea had already been discredited from within ASEAN itself. The cooperative security norm had displaced the target norm of ZOPFAN but did not override the doctrine of noninterference in ASEAN, which remained at the top of ASEAN's norm hierarchy. When noninterference itself became the target norm, as in the case of flexible engagement, norm diffusion failed.

Both norms had insider proponents, but in the case of cooperative security, it was a regional network: ASEAN-ISIS. The insider proponents in the second case were two individuals, Malaysia's Ibrahim and Thailand's Pitsuwan. This was clearly a factor explaining the variation between the two cases.

The cooperative security norm could be grafted more easily into ASEAN thanks to the existence of two prior receptive norms (one that rejected a balance of power approach to regional security involving multilateral military pacts and the other being the Indonesian concept of regional resilience) in the ASEAN framework. There were no such norms to host flexible engagement.

Finally, cooperative security offered greater scope for enhancing ASEAN's prestige. It enabled ASEAN to acquire a broader regional relevance and role. Flexible engagement had no such appeal. Instead, it threatened to undermine both ASEAN and the ARF.

Alternative Explanations

Can the variation be better understood by alternative explanations? To seek explanations at the systemic level by linking the prospects for norm diffusion to the impact of the end of the Cold War on the global normative environment—as would be consistent with a structural constructivist framework—would not suffice. The end of the Cold War certainly helped the diffusion of the cooperative security norm by highlighting the contribution of the CSCE in easing East-West tensions, thereby creating an imitation effect of the norm. This inspired Western norm entrepreneurs such as Canada, which was part of CSCE and its CBM regime to advocate similar efforts in Asia. Moreover, the end of the Cold War created the need for a new Asian security order in light of the retrenchment of the U.S. and Soviet military presence in the region. But the end of the Cold War had a similar impact on the other norm. Both common security and humanitarian intervention were rendered more prominent after the end of the Cold War, the former because of the success of the OSCE and the latter because of the West's new security agenda focusing on democratic “enlargement” and concerns over famine and genocide in Africa and ethnic cleansing in the Balkans. Hence, the end of the Cold War itself cannot explain the pattern of norm diffusion in Southeast Asia, or why cooperative security was relatively more successful than humanitarian intervention.

There are three other possible explanations to be considered: realist, functionalist, and domestic politics. A realist perspective would explain the prospect of norm diffusion in terms of the distribution of power at the global and regional level. A popular strand of realist thinking sees the engagement of the United States in the regional balance of power as the primary determinant of Asian security order and a basic motivating factor behind the security policies of many Asian states. Hence, the acceptance of any new norm to reorganize ASEAN should have depended primarily on U.S. attitude and preferences, or by the regional actors' calculation of the impact of the new norm in keeping the United States engaged in the region. Going by this logic, cooperative security, which was initially feared and opposed by the United States, should have been rejected, while the flexible engagement, which conformed more to the style of regional interactions preferred by the United States and the EU, relatively more powerful actors in strategic and economic senses respectively (The EU had threatened sanctions against ASEAN), should have been accepted. But the outcome of normative contestation in Asia, as discussed in the case studies, was exactly in the opposite direction—a damning indication of the limitations of the realist framework.

The United States, as discussed earlier, itself had rejected cooperative security, at least initially. Hence, if U.S. power is what decisively shapes Asian security order, the initiative by the normally pro-U.S. ASEAN members to create a new regional security institution should not have been successful. Some realists have tried to move around this anomaly by arguing that the ARF was possible because ASEAN members saw it as a way of maintaining a balance of power in the Pacific by ensuring the continued engagement of the United States in the post–Cold War period when there were concerns regarding a possible U.S. military withdrawal from the region and when China's power was rising. Hence, Leifer's assertion that “the ARF was primarily the product of a post–Cold War concern … about how to cope institutionally with America's apparent strategic retreat from East Asia.”144

Leifer 1999, 116. See also Dibb 1995, 38.

But this perspective suffers from major gaps. First, the goal of keeping the United States strategically engaged in the region through the ARF was supported only by Singapore and Thailand, but not by Indonesia or Malaysia. Second, if the real aim was to ensure a stable regional balance of power, then this could have been more effectively addressed by offering military access to the United States to offset the loss of its bases in the Philippines. Indeed, this is precisely what Singapore did in 1990 when it offered access to its air and naval facilities to the U.S. Pacific forces. But Singapore's move was not matched by other ASEAN countries, and Malaysia was highly critical of Singapore's move.145

On intra-ASEAN differences over the U.S. military presence, see Acharya 2001, 131.

Interviews by author with Chinese Foreign Ministry officials, February 1999, Beijing.

What about power distribution at the intra-regional level? If this was crucial, then the diffusion of cooperative security should have depended on the attitude of the more powerful East Asian and ASEAN states, such as China, Japan, or Indonesia. But as the empirical discussion shows, China was initially reluctant to accept cooperative security and came around only after ASEAN had assumed leadership of the institution-building process and reconstructed the norm. Japan's role in pushing for cooperative security was also ambivalent. Sections in the Japanese policy establishment were clearly worried that such an institution would undermine the rationale for the U.S.-Japan defense alliance, the cornerstone of Japanese security policy. Despite an occasional initiative, Japan clearly deferred to the role of ASEAN and, as has been suggested, borrowed from ASEAN-ISIS's ideas about institutionalizing cooperative security. Within ASEAN itself, the pattern of power distribution is not overly hierarchical. No ASEAN country, including Indonesia, was in a power position to impose its preferred norm over the others. Hence, no serious link can be established between the acceptance of the cooperative security norm and intra-regional power differentials in Southeast Asia or East Asia.

Functionalist perspectives see Asian regional institutionalization primarily as a response to growing intra-regional interdependence.147

A key proponent of this view, Peter Drysdale, contends that the “main impetus” for Asia Pacific regionalism “derives directly from the forces of East Asia industrialization. It is to preserve the conditions needed to sustain the positive trend of rapid economic growth and the market-driven integration of Asia Pacific economies which derives from that growth.” Drysdale 1996, 1. See also Drysdale 1988; and Dobson and Lee 1994.

Interview by author with Surin Pitsuwan, 30 January 2001, Bangkok, Thailand.

Domestic politics (regime security concerns) may better explain why the flexible engagement concept found lesser acceptance than the cooperative security norm. Those who backed a more interventionist ASEAN—Ibrahim, Pitsuwan, and Siazon—were representing its more democratic polities, while the most vocal opponents of the norm, such as Vietnam and Burma, presided over illiberal regimes. A flexible engagement policy, given its roots in humanitarian intervention, would have undercut the legitimacy of these three regimes. This consideration overrode whatever utility the states could perceive from Pitsuwan's idea of making ASEAN more effective. Cooperative security did not pose a similar threat to these regimes, because it had no CSCE-like “human dimension” calling on the member states to offer greater protection for human rights.

But this situation strengthens, not weakens, my central argument that ASEAN's regional cognitive priors mattered in explaining its divergent responses to cooperative security and flexible engagement. This is because the authoritarian domestic politics in ASEAN were already incorporated into ASEAN's normative prior. The noninterference norm in ASEAN was to a large extent geared toward authoritarian regime maintenance.150

This is true of most Third World regions. See Clapham 1999.

Realist, functionalist, and domestic political explanations thus by themselves fail to explain ASEAN's contrasting response to two new transnational norms. A more credible explanation must consider the role of ideational forces and the conditions for their localization. What is important here is not how the prescriptive ideas backed by outside advocates converted the norm-takers, but how the cognitive priors of the norm-takers influenced the reshaping and reception of foreign norms. This was not a static fit, but a dynamic act of congruence-building through framing, grafting, localization, and legitimation in which the local actors themselves played the central role.

This perspective also explains a key puzzle of Asian regionalism: why it remains “under-institutionalized,”151

despite shifts in the underlying material conditions and bargaining contexts, such as the intra-regional balance of power and economic interdependence. The path-dependency created by localization reveals much about the absence of “European style” regional institutions in Asia despite recent efforts at strengthening and legalizing their institutional framework to cope with new pressures.Conclusion

Local actors do not remain passive targets and learners as transnational agents, acting out of a universal moral script to produce and direct norm diffusion in world politics. Local agents also promote norm diffusion by actively borrowing and modifying transnational norms in accordance with their preconstructed normative beliefs and practices. Until now, agency-oriented explanations of norm diffusion tended to be static and failed to explore how existing norms helped to redefine a transnational norm in the local context. This article has offered a dynamic theory of localization in which norm-takers perform acts of selection, borrowing, and modification in accordance with a preexisting normative framework to build congruence between that and emerging global norms. This framework is then tested in studying ASEAN's response to two major security norms of the post–Cold War era: common security and humanitarian intervention. Out of these two norms, the former found greater acceptance than the latter, because common security fit more into the conditions that facilitate localization, such as the positive impact of the norm on the legitimacy and authority of key norm-takers, the strength of prior norms, the credibility and prestige of local agents, indigenous cultural traits and traditions, and the scope for grafting and pruning presented by foreign norms.

The framework of localization proposed in this article is helpful in understanding why any given region may accept a particular norm while rejecting another, as well as variation between regions in undergoing normative change. The framework also offers an alternative to explanations of norm diffusion and institutional change that focus on powerful states or the material interests of actors derived from functional interdependence. In so doing, this article advances the cause of generalizing and theory-building from the milieu and behavior of norm-recipients, especially non-Western actors whose agency role has been sidelined in the literature on norm diffusion.

While this article's empirical focus is Southeast Asia, comparative work could be undertaken using this framework to investigate how these and other norms spread through the international system, from the global to the local and from region to region. For example, the spread of norms about human rights and democracy can be seen in terms of a localization dynamic, in which prior and historically legitimate local normative frameworks play an important role in producing variations in their acceptance and institutionalization at different locations.152

Ignatieff's work on human rights notes the dangers of overestimating the West's “moral prestige” and ignoring the Third World's capacity for resistance. Ignatieff 1998, 94. Appadurai's anthropological perspective illuminates three related processes of ideational change as a subset of cultural globalization: how local communities are ‘inflected’ by global ideas, how global ideas are indigenized and the resulting local forms are subsequently ‘repatriated’ back to the outside world, and how local forms (such as Hinduism) are globalized. Note the similarities between this and the concept of localization in Southeast Asian studies. Appadurai 1996.

The recent institution-building dynamics in Southeast Asia also suggest that shifts in the global normative environment alone do not produce normative and institutional change at the regional level at the expense of preexisting normative frameworks and social arrangements. One implication is that it would be unrealistic for advocates of regionalism in Asia to expect that these institutions will any time soon develop the legalistic attributes of European regionalism, the source of much theorizing about regional institutions. The localization dynamics highlighted in this article should also serve as a note of caution to those expecting ideas and institution-building models successful in one part of the world to be replicated elsewhere. This does not mean institution building in Asia or elsewhere is doomed to failure. What it suggests, however, is that in Asia as elsewhere in the developing world, institution change brought about by norm diffusion is likely to follow a progressive and evolutionary trajectory through the localization of international multilateral concepts, without overwhelming regional identity norms and processes.

References

REFERENCES

The trajectory of localization and conditions for progress

Local responses to transnational norms

- 1115

- Cited by