The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) triggered a global pandemic and economic contraction unlike anything seen for roughly a century. COVID-19 is less lethal than many other recent diseases, such as Ebola, Avian Influenza, and Tuberculosis.Footnote 1 However, the virus that causes COVID-19—severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)—appears to be calibrated to inflict maximum harm on the contemporary world economy. The virus spread rapidly by taking advantage of globalization and interconnectedness. Unlike virus transmission in the 2003 SARS epidemic, COVID-infected individuals unknowingly became super-spreaders as their symptoms developed slowly and often remained mild. Epidemiologists recommended flattening the epidemic curve by effectively shutting down large segments of the economy, and many governments obliged.

It is tempting to leave research on COVID-19 to scientific experts such as epidemiologists, immunologists, and virologists. Political scientists cannot eradicate the virus or cure the disease. However, the impact of COVID-19 is ultimately determined by politics. As Thomas Hale observes, “COVID-19 attacks the human body, but it is largely the body politic that defends us against it.”Footnote 2 Why are some countries more vulnerable to major crises such as global pandemics? Why do some governments respond more quickly and aggressively? How do domestic and international institutions transform in response to major shocks? On these matters, political scientists are the relevant experts.

I will argue that the politics of COVID-19 is the politics of crisis. Crises compel leaders to make high-stakes decisions under conditions of threat, uncertainty, and time pressure. Crises are important because of their human consequences and their political repercussions. They are also likely to increase in frequency along with economic globalization and climate change. There is now well-developed scholarship on the politics of crises in specific issue areas such as finance,Footnote 3 energy,Footnote 4 natural disasters,Footnote 5 and pandemics.Footnote 6 The COVID-19 pandemic provides an impetus to unify these literatures and restore the politics of crisis as a central research agenda in international relations. Doing so will require combining theoretical insights from international political economy (IPE) and security studies, which bring different strengths and weaknesses to the enterprise. I will propose a framework for studying crisis politics and consider major puzzles surrounding causes, responses, and transformations.

The Politics of Crisis and COVID-19

I define a crisis as a situation that threatens significant harm to a country's population or basic values and compels a political response under time pressure and uncertainty.Footnote 7 The three elements of threat, urgency, and uncertainty are defining features of crises.Footnote 8 Among the most prominent examples are financial crises, energy price shocks, nuclear accidents, major natural disasters, terrorist attacks, and violent conflict. Pandemics such as COVID-19 also fall under the umbrella of crises.

In this section, I will develop a framework for theorizing about crises in international relations. I will begin by briefly reviewing how the politics of crisis came to be neglected in the field: IPE has increasingly focused on explaining routine, ongoing economic relationships, while international security focuses disproportionately on militarized crises at the expense of others. I will then draw contrasts between open economy politics—the dominant mode of theorizing in IPE—and crisis politics. The core features of crises—threat, time pressure, and uncertainty—lead to patterns of interaction and decision-making distinct from those of routine economic flows. However, the degrees of threat, time pressure, and uncertainty vary across crises, within the same crisis by issue, and according to specific phases of a crisis. It is thus critical to consider variation in these factors and their potential consequences for political and economic outcomes.

Refocusing Attention on the Politics of Crisis

In recent years, the field of international relations has divided itself primarily into IPE and security. Crises that disrupt economic activity fall naturally under the umbrella of IPE. In fact, IPE was born out of global turbulence in the 1970s: early scholarship devoted considerable attention to the causes and consequences of economic and energy shocks.Footnote 9 However, IPE has largely shifted its focus to routine, ongoing economic relationships in areas such as trade, investment, and foreign aid.

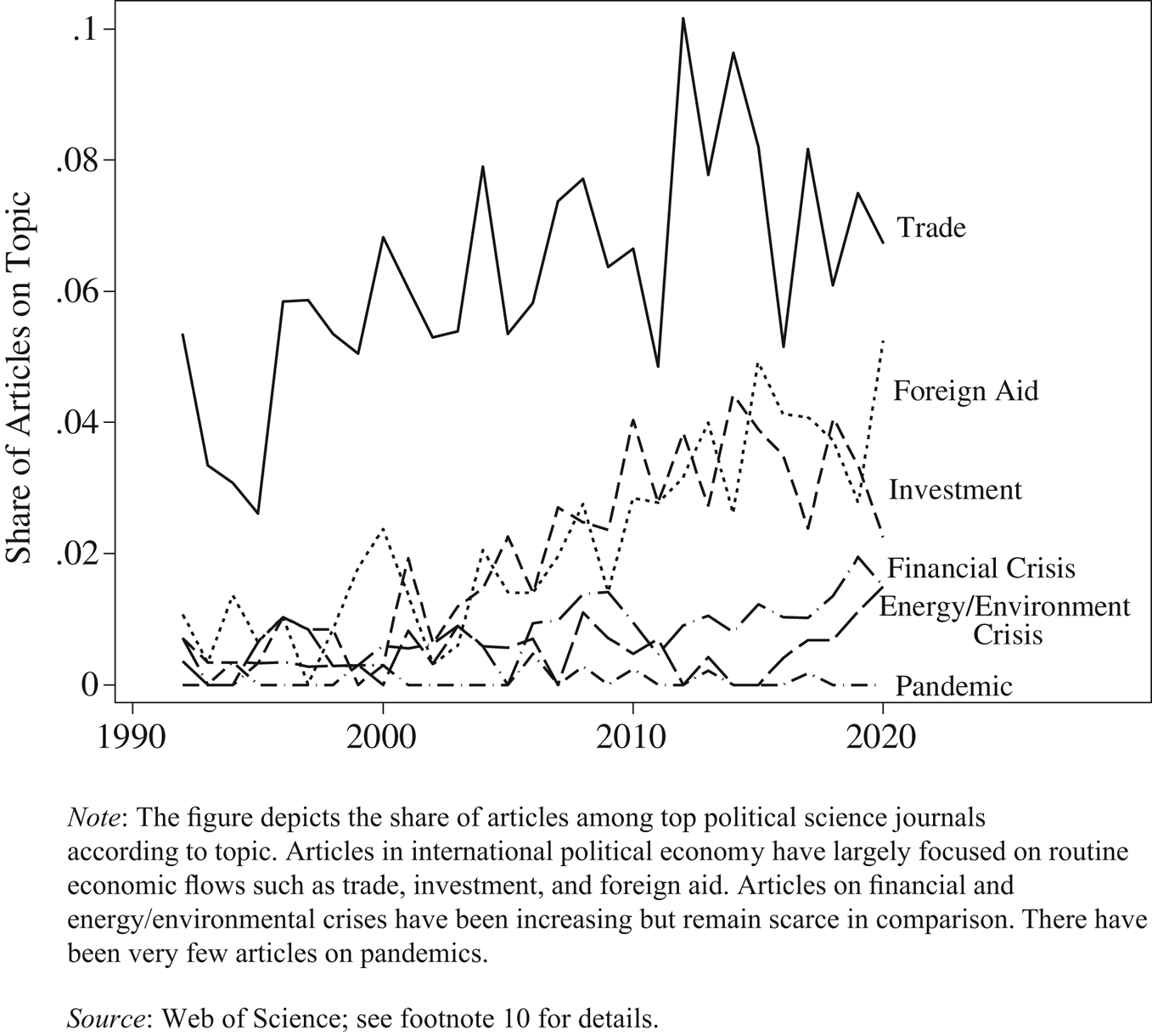

Figure 1 surveys top journals in political science, comparing articles published on several topics typically associated with open economy politics—trade, investment, and foreign aid—and the politics of crisis in several domains—finance, energy and the environment, and pandemics.Footnote 10 The figure shows familiar trends: a subfield once dominated by trade has gradually turned attention to other economic flows such as investment and foreign aid. The 2008 global financial crisis elevated the study of financial crises from relative obscurity. Attention to energy and environmental crises has picked up more recently, thanks to concerns about climate change. However, the share of publications on both topics remains relatively low. There is very little work published on pandemics in top political science journals: only nine articles in the entire period from 1992–2020.

Figure 1. Share of articles in top political science journals by topic (1992–2020)

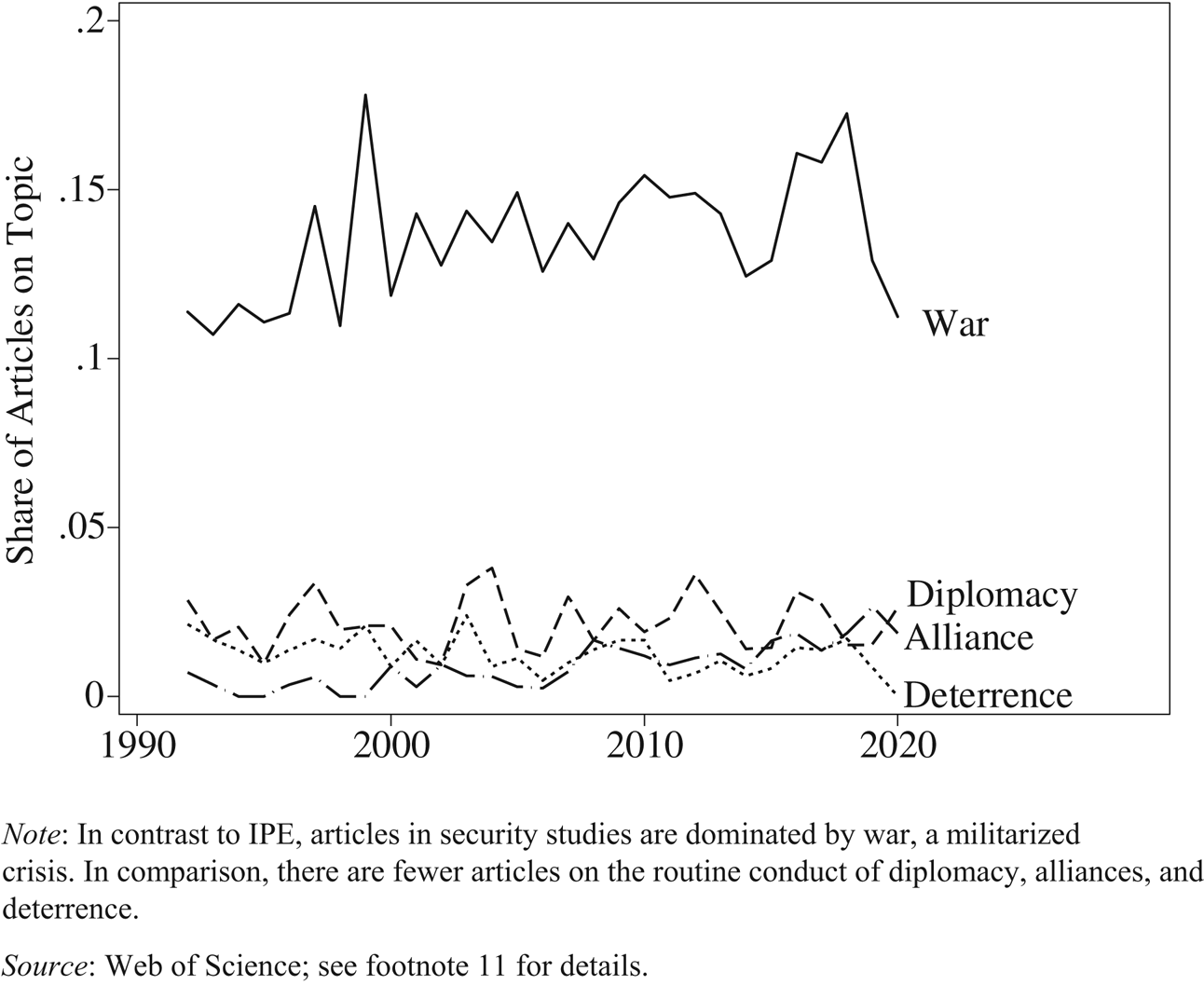

Security studies presents an intriguing contrast to IPE, as illustrated in Figure 2. The figure was generated using a procedure analogous to Figure 1, but instead focusing on topics that are prominent in security studies.Footnote 11 In contrast to IPE, which is dominated by the study of routine, ongoing economic interactions, security studies is dominated by war, or more broadly militarized conflict. War clearly satisfies the definition of a crisis, being characterized by significant material threat, time pressure, and uncertainty. Like other crises, major wars unsettle existing political relationships and often lead to fundamental transformations in domestic and international politics.Footnote 12 Even when security scholars study the routine conduct of international relations – such as through diplomacy, alliances, or deterrence – it is often framed around obtaining or preventing advantages in militarized conflict. Despite calls for broader conceptualizations of security that move beyond traditional domains,Footnote 13 security studies scholars typically use “crisis” interchangeably with “military crisis.”Footnote 14

Figure 2. Share of articles in top political science journals by topic, security topics (1992–2020)

As the subfields have evolved in practice, IPE is the study of the mundane. International security is the study of war, an extraordinary event. Crises that trigger major economic upheavals—such as financial panics, energy and environmental shocks, and pandemics—have faced relative neglect: they are neither mundane nor militarized. Such crises are becoming more frequent due to factors such as globalization and climate change.Footnote 15 The COVID-19 pandemic presents a compelling rationale to place crisis politics front and center in the study of international relations.

Open Economy Politics and Crisis Politics

Since roughly the 1990s, IPE has been dominated by the open economy politics model, which aggregates up from individual preferences to institutions to international interaction. Using rationalist assumptions, open economy politics begins by deriving preferences from an individual or group's position in the international economy. Institutions aggregate these often-competing interests, determining which voices are weighed more heavily in policy outcomes. Finally, states bargain internationally based on aggregated preferences.Footnote 16

Open economy politics has proven remarkably useful for theorizing the politics of routine, cross-border economic flows. However, critics argue that it has promoted an intellectual monocultureFootnote 17 and insularityFootnote 18 that neglect major changes taking place in world politics, such as increasing volatility in financial and energy markets.Footnote 19 Some have argued that theoretical and empirical rigor make IPE scholarship inaccessible.Footnote 20 This critique has faced compelling pushback: the field is unlikely to make progress by abandoning the scientific method or avoiding entire avenues of investigation.Footnote 21 However, the accumulation of rigorous, empirical work has raised nontrivial questions about the core microfoundations of open economy politics, including the assumption that individuals hold preferences consistent with their theorized economic self-interest,Footnote 22 the translation of individual preferences into policy,Footnote 23 and the exogeneity of domestic preferences to international interaction.Footnote 24

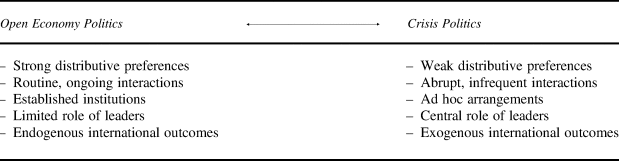

These problems are magnified during a crisis. The defining features of crises—threat, time pressure, and uncertainty—create conditions under which the microfoundations of open economy politics are unlikely to hold. Table 1 presents a schema outlining the core assumptions of open economy politics and contrasts them to archetypical features of crisis politics. As I will discuss, many aspects of crises fall somewhere between the extremes, but it is useful to begin with a clear dichotomy.

Table 1. Open economy politics and crisis politics: archetypes

A foundational assumption of open economy politics is the presence of clear preferences derived from an individual actor's position in the world economy. These preferences lead to distributive conflict over policy choices: for example, import-competing firms prefer high trade barriers, while export-oriented firms prefer the opposite.Footnote 25 Open economy politics typically models contestation over routine, ongoing economic interactions in areas like trade, investment, and aid. In contrast, crises are abrupt, infrequent events, and distributive conflict based on economic preferences tends to be less salient due to the uncertainty, time pressure, and threat associated with crises. Because crises are infrequent and often involve novel challenges and policy responses, they can create fundamental uncertainty about what government action will produce the greatest utility, even for specific individuals. Furthermore, time pressure compels a significant government response before individuals sort out this uncertainty and formulate a clear set of preferences. The presence of a potentially devastating threat raises concerns about personal and national survival, which can outweigh the utility individuals place on distributive economic outcomes.

Open economy politics also assumes that interest aggregation occurs in a predictable manner through established institutions, such as rules governing legislation, lobbying, or the selection of politicians. The framework generally minimizes the role of political leaders, except insofar as they are concerned about political survival and hence influenced by individual preferences and their aggregation. The core features of crises make these assumptions problematic. Existential national threats raise the stakes for leaders and magnify their role in crisis management. The uncertainty and time pressure associated with crises often compel reliance on ad hoc mechanisms such as impromptu working groups and emergency orders, which allow for rapid decision-making and override constraints from established institutions.Footnote 26 Crises thus tend to magnify the influence of leaders over policy outcomes while diminishing the role of established institutions.

Finally, open economy politics assumes that international outcomes are endogenous to domestic processes: national objectives at the international level are determined by domestic preferences and institutions. However, many crises originate from other countries and propagate directly or indirectly through the actions of foreign actors. Choices by foreign actors and international macro processes are often important triggers for crises, and crises can fundamentally reshape domestic preferences and institutions. Theorizing from the ground up from preferences to institutions to international interaction can be highly problematic under these conditions, in which the causal arrow points in the opposite direction.Footnote 27

As an example of how scholars theorize crisis politics outside of IPE, consider the crisis bargaining literature in security studies.Footnote 28 As the terminology implies, crisis bargaining concerns the decision-making of leaders under threat, urgency, and uncertainty. Insofar as domestic politics comes into play, the focus is primarily on valence: did the political leader secure a favorable outcome for the country as a whole? Did the leader damage the country's honor or reputation? Did the leader publicly commit to a position and then back down? Crises with significant economic consequences raise analogous questions: was the crisis resolved successfully? Was response to the crisis managed competently compared to other countries? Were the leader's public statements consistent with the government's actions?

The crisis bargaining literature does not typically assume domestic actors have well-defined economic preferences over distributive outcomes. It is not that distributive conflict is absent. One could stipulate a crisis bargaining game by starting from domestic conflict between those who prefer escalation based on their economic utility (such as arms producers) and those who are economically exposed (such as industries located in border areas). The implicit assumption is that decision-making under crisis is not fundamentally about this sort of distributive economic conflict, but about leaders making high-stakes decisions concerning fundamental national interests.

These are also reasonable assumptions when considering the politics of COVID-19. Pandemic policy response involves significant tradeoffs, such as curtailing economic activity to save lives. However, the unsettled science and conflicting information about COVID-19 meant critical decisions were made before individuals had a clear sense of their preferences: for example, parents could not easily judge whether it was in their economic self-interest to close schools to prevent infection or open schools to enable work. Leaders frequently relied on ad hoc mechanisms such as task forces, working groups, and emergency declarations to sidestep established institutions and make rapid, extraordinary decisions. The pandemic was defined by international contagion and the disruption of domestic political processes by an externally originated threat. COVID response came to be seen broadly in terms of national success or failure, with case and death statistics playing the role of national performance indicators despite their limitations and susceptibility to manipulation. In short, the politics of COVID-19 is best understood as the politics of crisis.

Variation in Threat, Uncertainty, and Time Pressure Across and Within Crises

Although Table 1 dichotomizes open economy politics and crisis politics for illustrative purposes, there is a continuum between the extremes. Not all crises neatly occupy the right-hand side of the table. It is thus crucial to consider how attributes of specific crises violate the standard assumptions of open economy politics, and how these violations influence political and economic outcomes. There are three principal sources of variation.

First, threat, uncertainty, and time pressure can vary both across crises and over time during a single crisis. A major, unprecedented crisis triggered by contagion will approximate the right-hand side of Table 1, while prolonged or repeated crises of a similar nature can become routinized and begin to resemble the left-hand side. For example, the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic were characterized by a life-threatening, rapidly propagating threat and pervasive uncertainty over basic questions such as the nature of the virus and efficacy of response measures. This compelled leaders to respond quickly using ad hoc mechanisms and made it difficult for individuals to form preferences over policy responses. On the other hand, financial crises in countries such as Mexico and Argentina recur with sufficient frequency that uncertainty and perceived threat may be mitigated. Climate change is characterized by significant threat and uncertainty, but the most serious consequences are not immediate, reducing time pressure: political contestation thus often revolves around attempts to generate time pressure around salient natural disasters and commitments to deadlines.

Second, within a single crisis, there can be variation in uncertainty and time pressure according to specific policy issues and response measures. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was considerable uncertainty over the preferability and urgency of school, business, and border closures, which hinged on how the virus is transmitted and the vulnerability of specific populations. However, there was greater clarity about the consequences of financial support for unemployed workers and lower policy interest rates. New policies—such as the introduction of quantitative easing by Japanese financial authorities in 2001—will tend to introduce greater uncertainty compared to familiar policy measures. Time pressure will be intense for policies that directly address the root causes of an ongoing crisis—such as attempts to forestall a nuclear meltdown—but can be less severe for measures to manage the consequences, such as economic support schemes and reconstruction plans. Policy responses subject to less urgency and uncertainty are more likely to fall under established patterns of distributive politics and institutional aggregation.

Third, the following sections outline core puzzles related to the causes of crises, crisis response, and the transformational effects of crises. Each of these aspects is associated with distinct patterns of threat, uncertainty, and time pressure. Open economy politics can be useful for examining the aspects of crises where conditions align with the framework's core assumptions. However, a different approach is needed to understand some of the defining features of crises that occupy the right-hand side of Table 1. In the following sections, I develop this approach by drawing on existing scholarship on crises in a variety of domains and through application to the politics of COVID-19.

Causes of Crises

The first, basic puzzle of crises is why governments allow them to happen. For political leaders, crises come with significant costs and few benefits. Retrospective reports frequently reveal that governments failed to implement cost-effective preventative measures that could have forestalled or mitigated a crisis.Footnote 29 International security scholars have developed a large literature around the inefficiency of war puzzle, which asks why leaders engage in war when diplomacy could achieve the same outcome without the cost of fighting.Footnote 30 It is useful to analogously begin with a “crisis inefficiency” puzzle: why do governments face costly crises rather than adopting adequate preventative measures?

The causes of crises can be broadly separated into factors exogenous and endogenous to politics. Crises are often triggered by events that politicians do not directly control, such as a natural disaster, asset price collapse, or the mutation of a new virus. However, once an exogenous event occurs, ex ante and ex post political decisions determine the consequences for society. Not all exogenous shocks trigger crises. COVID-19 appears to be less lethal and less contagious than Ebola or SARS.Footnote 31 However, it has spread far more broadly and claimed many more victims. Although this may be due in part to non-political factors, there have also been glaring preventative failures among major actors such as the governments of China and the United States and the World Health Organization.Footnote 32

Why do some governments fail to implement policies to prevent crises or mitigate their potential consequences? Open economy politics offers important insights. A classic answer is divergent preferences between organized interest groups and the general public. Diffuse voters face greater barriers to collective action than organized interest groups, and this imbalance can be further exacerbated in certain institutional settings. For example, while aggressive regulation can forestall banking crises, benefiting society at large, it reduces the profitability of financial institutions. Hence, political institutions such as proportional representation, which elevate the relative influence of organized interest groups, can lead to less prudential regulation.Footnote 33 Regulatory capture in nuclear energy follows a similar logic: utility companies effectively socialize the cost of disasters by underinvesting in accident prevention.Footnote 34 Natural disasters related to climate change are analogous, pitting the broader interests of society against businesses and workers tied to fossil fuels.Footnote 35 However, this distributive logic is less convincing for preventative measures—such as public infrastructure investments to mitigate natural disasters or pandemic surveillance—that impose no obvious costs on organized groups. Two features of crises—ex ante uncertainty and international contagion—are also important potential sources of preventative failure.

Uncertainty as an Impediment to Crisis Prevention

Preparation for a crisis occurs under normal conditions without heightened threat or time pressure. This means some of the standard assumptions of open economy politics are largely plausible for explaining variation in prevention: distributive conflict can be an important impediment, and decision-making tends to occur through established institutional mechanisms. However, one of the core characteristics of crises—uncertainty—is particularly heightened before a crisis occurs. The infrequency of crises contributes to pervasive uncertainty ex ante: not only are the characteristics and consequences of future crises unknown, but it is also difficult to ascertain their likelihood and relative frequency. Heightened uncertainty can decrease the likelihood of successful preventative policies.

The infrequency of crises can skew preferences and make voters and policymakers less likely to invest in preventative measures. Assessments of low-probability, high-consequence events are notoriously subject to psychological biases.Footnote 36 Major natural disasters can follow cycles far longer than the human lifespan.Footnote 37 Though voters may express opinions about crisis prevention if pressed, they are unlikely to give the topic much thought except when a crisis actually occurs. Furthermore, politicians may not have sufficiently long time horizons to internalize the costs of crises.Footnote 38

These biases are further compounded by the fact that the benefits of prevention are often invisible: either there is no crisis, or a crisis is successfully forestalled. Even when prevention is in their economic self-interest, voters tend to disproportionately reward politicians for visible crisis response rather than for invisible preventative measures.Footnote 39 This suggests that empowering voters is insufficient to facilitate adequate crisis prevention. Other mechanisms—such as delegation of authority to insulated bureaucracies with clear mandates and longer time horizons—may be necessary to counterbalance the biases of voters and policymakers.Footnote 40 However, this raises additional questions about why some governments are willing and able to delegate such authority.

The lack of direct attention to crisis prevention from policymakers and voters means vulnerability is often influenced by spillover effects from institutional choices and policy outcomes in other domains. For example, financial crises are more likely in countries with well-developed securities markets, which makes banks more prone to risk-taking with foreign capital.Footnote 41 Policies that supported small, decentralized banks in the United States led to less diversification and more frequent crises than in Canada, which developed a nationwide branch banking system.Footnote 42 For COVID-19, a plausible source of such spillover is variation in the strength of civil society. COVID-19 prevention at the individual level has features of a classic collective action problem: precautionary measures involve personal costs, but the benefits are diffuse for many in society. For young, healthy people with no medical risk factors, actions like wearing a mask, closing their business, or following social distancing rules are personally costly to varying degrees, but the direct personal benefit is small. This is especially true if the rest of society diligently follows precautionary measures and limits contagion. An important potential source of non-policy variation is then whether societies can achieve cooperative behavior without coercive government intervention.Footnote 43 This is in turn influenced by the strength of civil society and social capital, which are also important factors in the resilience of local communities to natural disasters.Footnote 44

Experience and knowledge of prior crises can reduce uncertainty and increase salience among policymakers and voters, facilitating preventative policies. Variation in prior experiences is often idiosyncratic and country specific. For example, nuclear regulators in the United States and France required waterproofing of emergency backup generators after vulnerabilities were revealed during 9/11 and the 1999 flooding of the Blayais nuclear plant. Japan, which had not experienced prior flooding, forwent waterproofing, contributing to tsunami inundation and the core meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi plant in 2011.Footnote 45 Similarly, countries with prior experience with coronavirus diseases such as SARS and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) appear to have implemented more effective preventative measures prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 46 An important question is how lessons learned from foreign crises spread: when are lessons and responses confined to national borders, and when do they spread more widely? What kind of cooperation is needed to facilitate diffusion? When are voters willing to support prevention based on crises in faraway lands?

Preventing Contagion Through International Cooperation

International contagion is an increasingly salient cause of crises, and its management is an important aspect of crisis prevention. The globalization of economic ties, the movement of people, and information transmission means a crisis that occurs in one country can quickly explode into a global crisis with far-reaching consequences. Countries more open to globalization, such as democracies, may be more susceptible to experiencing crises through contagion.Footnote 47 Many countries faced sharp economic contractions during the 2008 financial crisis despite limited direct exposure to the US housing bubble. Similarly, COVID-19 emerged in China but led to a far greater number of deaths in other countries. The global nature of contemporary crises necessitates renewed attention to systemic sources of instability, a topic that open economy politics tends to neglect due to its bottom-up theorizing.Footnote 48

International cooperation can play a significant role in overcoming collective action problems that contribute to underinvestment in international crisis prevention. Early theorizing on the politics of global stability emphasized the role of a hegemon, a preponderant state that provides global public goods such as lender-of-last-resort lending.Footnote 49 Although predictions of US hegemonic decline have repeatedly proven premature,Footnote 50 hegemonic stability theory fell out of fashion as scholars questioned its core assumptions, and as institutionalized cooperation—what became known as neoliberal institutionalism—appeared to present a robust alternative.Footnote 51 Recent developments suggest a revisiting of this debate.

First, institutionalized cooperation has itself become an arena of intense contestation, with the proliferation of competing institutions and withdrawal of core members such as the United States and United Kingdom. Institutional renegotiation and exit are not new and can have beneficial effects on global governance.Footnote 52 However, contestation can also hamper crisis prevention by paralyzing institutions or facilitating the proliferation of duplicative, uncoordinated international organizations.Footnote 53 The pernicious consequences of contested multilateralism were illustrated during the COVID pandemic by US-China tussling over the WHO, which undermined the credibility of the institution at a critical moment.Footnote 54

Second, hegemonic stability theory and neoliberal institutionalism rest on rationalist assumptions. The tone in IPE was set early on when Stephen Krasner made the case for structural explanations by asserting, “Stupidity is not a very interesting analytic category.”Footnote 55 The Trump administration raises serious questions about this foundational assumption. Stupidity can be magnified and weaponized by structural conditions. A foolish hegemon is itself a source of global instability. We may thus posit a theory of hegemonic stupidity: the international system becomes unstable and prone to crisis when the hegemon is stupid or erratic. One hopes this theory remains difficult to test empirically.

Response to Crises

Once a crisis has started, a central question is how quickly and effectively a government can terminate it. This is perhaps the sharpest distinction between crises and dominant topics in IPE such as trade, investment, and aid, where there is a normative case and assumed desirability for the economic relationship. To put it bluntly, a crisis is a bad situation. A good crisis is a crisis that is over. What prevents governments from ending crises quickly once they start?

Existing work in open economy politics tends to focus on distributive conflict and short time horizons as an impediment to crisis resolution. Macroeconomic adjustments can be delayed by distributive concerns and aversion toward costs that need to be imposed on specific actors.Footnote 56 Concentrated interest groups may lobby in favor of policy measures that prolong resolution and impose greater costs on society. The use of regulatory forbearance in banking crises is a good example.Footnote 57 Both bank and government leaders may prefer to suspend accounting rules in order to postpone a reckoning, even if forbearance magnifies the burden of bad debt for their successors and the public. Hence, an important source of variation in crisis response is how institutions aggregate the interests of organized interest groups and voters. For example, democratic institutions empower voters and reduce the use of public funds to bail out banks.Footnote 58

Distributive conflict and institutional biases are useful for explaining some important aspects of crisis response. However, it is also critical to consider the core features of crises—uncertainty, time pressure, and threat—along with how these factors elevate the role of leaders and ad hoc decision-making compared to ordinary times.

Uncertainty and First-Mover Disadvantage

Uncertainty is an important source of variation in crisis response. Uncertainty is particularly heightened when governments confront a new or unfamiliar form of crisis. In such cases, the lines of distributive conflict become less clear, reducing the role organized interest groups play in prolonging crises. However, uncertainty itself can emerge as an important impediment to effective crisis resolution.

Responding to a novel or unfamiliar crisis forces policymakers to go through a messy process of experimentation, discovery, and potentially repeated policy failure. This can be a time-consuming process that prolongs a crisis and increases its severity. In contrast, policymakers responding to a similar crisis later can quickly implement successful policies discovered during earlier episodes. Oil price shocks are a good example of how familiarity facilitates more effective crisis response. In 1973, oil had become a resource vital to economic and military security, making sharp price increases an unprecedented, disruptive shock. Uncertainty about the duration of the price hike, the effectiveness of various policy measures, and the feasibility of alternative energy sources led to disorderly responses across industrialized countries. In contrast, government responses to oil price increases in the mid-2000s were far less chaotic, following a well-established playbook developed after the 1970s.

This variation in uncertainty and familiarity can create a “first-mover disadvantage” in crisis response. For example, when its 1990s financial crisis revealed the limitations of conventional monetary policy, Japanese financial authorities developed and carefully tested novel measures such as zero interest rates and quantitative easing over the course of a decade. During the 2008 crisis, central banks in other countries adapted these measures immediately and with little hesitation.Footnote 59

First-mover disadvantage is also a plausible feature of pandemic response. Epidemics such as Ebola, SARS, and MERS often inflict heavy casualties in countries where the virus originates, while countries afflicted later manage to keep the disease contained. Like COVID-19, SARS originated in China. However, most cases and deaths occurred in mainland China and Hong Kong, while the virus had a limited impact in countries experiencing outbreaks later. Coordination among global health authorities under the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network of the WHO enabled later-moving countries such as Canada, Singapore, and the United States to quickly recognize SARS cases. These countries were thus able to respond effectively by implementing quarantines and contact tracing.Footnote 60

One intriguing feature of COVID-19 is that first-mover disadvantage has not applied: early-movers like China, South Korea, and Japan appear to have responded more effectively than later-moving countries like the United States and Brazil. Although this may be partly attributable to non-political factors like the nature of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, shortcomings in information-sharing, learning, and international cooperation are also plausible reasons for the underperformance of late movers.

Time Pressure and Constraints

Time pressure is a defining characteristic of crises, and speed is an important element of crisis response: the severity of a crisis is often determined by how quickly governments react. Countries that responded quickly and aggressively to their first cases of COVID-19 appeared to experience less serious outbreaks.Footnote 61 Hence, it is important to consider constraints that may slow government reaction. A common claim is that democratic governments face obstacles to rapid response due to separations of power, veto players, and other institutional constraints.Footnote 62 However, the crisis bargaining literature has demonstrated that constraints can also be an important source of democratic advantage, for example by enabling credible commitment. Although credible commitment has less direct relevance for non-militarized crises,Footnote 63 there are other ways in which constraints may create counterintuitive advantages.

For example, when Japan confronted COVID-19, policymakers realized early on that the country's constitution provided no legal authority to restrict personal mobility except on a voluntary basis.Footnote 64 This foreclosed the use of draconian lockdowns adopted in other countries. Japan faced additional constraints in testing capacity and administrative mechanisms to coordinate pandemic response. However, knowledge of these constraints compelled the government to act quickly and enlist epidemiologists to devise solutions, leading to an approach focusing on high-risk situations for contagion: the three Cs of closed spaces with poor ventilation, crowded places, and close-contact settings.Footnote 65 This approach was supplemented with the distribution of cloth masks and an early emphasis on contact tracing to limit super-spreader events. Institutional constraints compelled Japan to develop an approach that placed relatively few restrictions on individual liberties and economic activity.

Under what conditions are democratic constraints a source of weakness, and when can they become a source of strength? The Japanese case suggests we need to think carefully about the nuances of political constraints, particularly who is constrained from doing what. With large Diet majorities, the Abe government faced few legislative constraints, but constitutional restrictions and local government authority over important aspects of pandemic response (such as business closure and testing) compelled a search for distinctive solutions.

When empirically evaluating variation in the speed of policy response to COVID-19, there is a potential endogeneity problem related to the detection of the first case. Countries like Japan and South Korea, which responded relatively early, were also among the first countries to record cases outside of China. To further complicate things, the detection of the first case is itself likely endogenous to government policies such as surveillance or the quality of healthcare: antibody tests suggest the virus may have spread globally by December 2019.Footnote 66 Thus, to accurately assess the speed of government response, we need at least three variables: the timing of the first actual COVID case, the timing of the first detected case, and the timing of the first government response. While the latter two are readily observable, the first remains uncertain in many countries.

Perceptions of Threat and Their Manipulation

Crisis response can be affected by variations in perceptions of threat. Beliefs and ideas about threat shape whether voters and policymakers perceive an exogenous shock as one demanding an urgent government response. The COVID-19 pandemic is not unique in causing significant casualties—Malaria and AIDS routinely claim hundreds of thousands of victims every year.Footnote 67 However, COVID-19 stands out for heavily afflicting citizens of advanced industrialized democracies in North America and Europe. Thanks to medical advances, citizens of these countries were largely spared from severe epidemics during their lifetimes. This may have contributed to a form of casualty aversion: epidemic deaths in the contemporary West are more likely to be perceived as preventable policy outcomes demanding an immediate government response, much like war casualties. Furthermore, the elevation of COVID-19 to a global crisis likely owes something to the high concentration of early casualties in Western states, reflecting implicit judgements about the relative importance of states and populations in the international system.Footnote 68

Policymakers sometimes seek to manipulate beliefs about perceived threat to resolve crises. The Trump administration sought to downplay the severity of COVID-19 by comparing it to seasonal influenza and allegedly calculated that Americans would grow numb to the escalating death toll.Footnote 69 Crisis prevention through pretense is not completely ludicrous: some crises have self-fulfilling dynamics, such as runs on banks or currencies.Footnote 70 A bank run can be forestalled by convincing enough deposit holders that there is no bank run. Unfortunately, this is not how a pandemic works: inaction fuels greater contagion. Some crises reflect an underlying fundamental threat that cannot be wished away, whether it be a pathogen or widespread insolvency.

Leadership and Ad Hoc Decision-making

The threat, uncertainty, and urgency associated with crises tends to magnify the role of leaders, giving them leeway to make decisions with wide-ranging consequences.Footnote 71 Some of the most exciting theoretical and empirical developments in international security in recent years have concerned the role of leaders and psychology in foreign policymaking.Footnote 72 This is an area where IPE lags behind, with its long-running emphasis on structural determinants of outcomes.Footnote 73 It is an area ripe for cross-fertilization. COVID-19 reinforces the point: leaders like Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro made a variety of consequential decisions on what can only be described as a whim. Government response also appears to follow a predictable fear-apathy cycle seen in other pandemics.Footnote 74

Crises often compel leaders to make rapid decisions by relying on ad hoc mechanisms. This can magnify bureaucratic and organizational pathologies that stymie effective response. The 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster was exacerbated by pervasive miscommunication and buck-passing among political leaders, bureaucratic regulators, and Tokyo Electric Power Company.Footnote 75 However, autonomous bureaucracies with clear mandates can also become a source of rapid response. In crises in 2008 and 2020 the US Federal Reserve used its independent authority to react quickly and massively, calming financial markets and forestalling international contagion.Footnote 76 Although the COVID pandemic generated significant uncertainty, the macroeconomic consequences were both relatively predictable and within the scope of the Fed's mandate. This illustrates how uncertainty and relative certainty often coexist within the same crisis, with important consequences for policy outcomes.

Transformation of Political and Economic Interactions

Crises can create opportunities for long-lasting, transformational change, leading to alterations in patterns of political and economic interaction that would have been otherwise unlikely.Footnote 77 Crises can magnify the long-term consequences of policy decisions and embed new ideas in institutions.Footnote 78 The role of critical junctures such as major wars is well recognized in the study of global order.Footnote 79 Crises can also play an important role in enabling energy system transformations and radical decarbonization to address global climate change.Footnote 80 Yet not all crises are associated with transformational change. Even in response to the same exogenous shock, some countries pursue sweeping changes while others cling to the status quo. Under what conditions do crises facilitate transformational change, and when do they result in statis?

Open economy politics adopts a partial equilibrium approach based on theoretically derived economic preferences.Footnote 81 The approach is thus not designed to explain transformational change, which is by its nature the disruption of equilibrium. Transformational change during crises is best understood as the alteration of the basic building blocks of open economy politics—preferences, institutions, and international interaction—in a shift from one equilibrium to another. For example, government initiatives to promote new industries during crises can become self-reinforcing through the emergence of new interest groups, such as renewable energy producers after the 1970s oil shocks.Footnote 82 During the Great Depression, the US Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1933 not only empowered exporters but also shifted industry preferences in favor of exports by dramatically increasing access to foreign markets, creating a new equilibrium around trade liberalization.Footnote 83

Crisis Characteristics and Transformational Change

Transformation hinges in part on the degree of threat, uncertainty, and time pressure associated with a crisis. In crises approximating the right-hand side of Table 1, leaders have significant leeway to implement major policy changes unencumbered by established institutional constraints. Ad hoc decision-making magnifies the ability of policymakers to pursue preferred objectives under the pretext of crisis response.Footnote 84 In crises or aspects of crises characterized by less severe threat and time pressure, it is more difficult for leaders to justify sweeping changes that bypass established institutions and procedures. Similarly, greater certainty about the consequences of proposed policy changes will increase the likelihood of resistance from entrenched actors seeking to avoid adverse consequences.

Some crises present a clear impetus for institutional creation or change. The shock of the 1957 Sputnik launch led to institutions such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and The Twelve-Country Study, the first international education assessment.Footnote 85 The visible demonstration of scientific advancement by the USSR created a clear rationale for Western investments in science and technology. On the other hand, reaching consensus on transformative solutions can be more difficult in the case of multifaceted challenges—such as addressing natural disasters caused by climate change—that necessitate the cooperation of diverse actors.

Transformation also depends on whether a crisis exposes clear shortcomings in existing institutional arrangements. A widespread perception that balance of power failed in the leadup to World War I engendered initiatives such as the League of Nations and the Kellogg–Briand Pact.Footnote 86 The 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster exposed flaws of Japan's “nuclear village”—cozy ties between nuclear regulators and utilities—and led to the creation of the independent Nuclear Regulation Authority.Footnote 87 On the other hand, perceptions that the “system worked” in 2008 by forestalling another Great Depression may have hampered international institutional reforms.Footnote 88

Holding crisis characteristics constant, a country's existing political institutions can contribute to variation in transformational change. Exogenous events that create a similar disruption for many countries—such as commodity price shocks in globalized markets—provide opportunities to empirically evaluate variation across political contexts. For example, during the 1970s oil shocks, proportional representation and corporatism may have facilitated energy system transformations by making politicians less sensitive to electoral backlash from energy consumers and providing compensatory mechanisms for economic losers.Footnote 89

Political Volatility and Public Perceptions of Crisis Response

Crises can also facilitate transformational change by generating political volatility that dislodges entrenched veto players. This can occur through the delegitimization of actors associated with failed crisis response. The perceived shortcomings of the Hoover administration during the Great Depression opened the way for legislative dominance by New Deal Democrats for nearly half a century.Footnote 90 Catastrophic defeat in World War II contributed to a culture of antimilitarism in Germany and Japan that persists to this day.Footnote 91 However, this process can also work in reverse: overseeing the 2011 Fukushima disaster delegitimized the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), a center-left party that broke the longstanding rule of the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). This allowed the LDP to return to political dominance and reverse transformational DPJ initiatives that emphasized denuclearization and renewable energy.Footnote 92

The last point suggests that to an important degree the transformational potential of COVID-19 depends on who was in power and on public perceptions about their performance during the pandemic. In many countries afflicted by COVID, there was a large but brief rally around the flag effect. US President Trump's approval rating hit all-time highs of his tenure, and leader approval soared in some hard-hit countries such as Italy, where Prime Minister Conte saw a 20 percentage point bounce in public support.Footnote 93 Intriguingly, positive health outcomes did not automatically translate into robust public support: Prime Minister Abe of Japan saw his approval rating sink to all-time lows despite reported COVID cases and deaths in Japan remaining at low levels.Footnote 94 The story was similar among US governors: governors of hard-hit states like Connecticut and New York experienced some of the largest gains in public support, and there was wide variation in approval ratings among governors of states with low COVID deaths.Footnote 95

Public perceptions about leadership can be important for the transformational impact of crises: the long-term consequences of a crisis are shaped not by the outcome per se but by how citizens perceive it.Footnote 96 In sharply polarized political contexts like the contemporary United States, voters tend to interpret information by relying on partisan cues.Footnote 97 This may allow leaders and parties to survive severe mishandling of a crisis except in extreme cases where individuals are directly affected, such as through the death of a close acquaintance.

Partisan cues are less salient in countries with limited political polarization, such as contemporary Japan.Footnote 98 However, even in such countries, uncertainty surrounding crises can make it difficult for voters to assess leadership performance. For example, Abe delegated Japan's COVID response to epidemiologists such as Shigeru Omi and Jin Oshitani, who became the faces of the government effort. Despite the merits of relying on scientific experts, the approach might have made Abe look aloof and unfocused compared to his foreign counterparts, who communicated about the pandemic directly and frequently. Variation in leadership style and how it shapes public perceptions and narratives can thus influence the long-term consequences of crises: it is a topic worthy of further examination.

Conclusion

COVID-19 directly and significantly impacted the daily lives of all of us. It is critical for scholars to develop theories and empirical approaches to better understand the politics of the pandemic. To do so, we need to refocus our attention on the politics of crisis as a core research agenda, combining the strengths of IPE and security studies. Standard assumptions in IPE need to be revised or supplemented by considering the core features of crises—threat, uncertainty, and urgency—and how they vary across and within crisis episodes. The research program can be organized around puzzles surrounding causes, response, and transformation. Why do governments face costly crises rather than adopting adequate preventative measures? What prevents governments from ending crises quickly once they start? Under what conditions do crises facilitate transformational change, and when do they result in statis?

The COVID-19 pandemic creates a window for transformative policy change with potentially long-lasting consequences: I will close by discussing several potential avenues for such change that are worthy of attention. Furthermore, political science as a discipline also faces a transformational opportunity in light of the pandemic. It is an opportunity well worth seizing.

Transformation of Policy

Like many prior crises, the COVID-19 pandemic can be a transformative moment. At least three possibilities are worthy of attention by scholars and policymakers. First, the pandemic has induced significant, large-scale behavioral change that governments can accelerate. The crisis has shut down long-distance travel and local commutes for many workers. Some localities are using the opportunity to redesign urban infrastructure in favor of eco-friendly transportation. Government support for technologies and investments that institutionalize greater interaction with less energy-intensive mobility will have long-lasting consequences for salient outcomes like climate change, work-life balance, and political geography.

Second, COVID-19 has the potential to transform domestic politics in many countries. COVID response has dramatically increased government intervention in society through restrictive measures and economic stimulus. Furthermore, COVID has highlighted and exacerbated long-simmering income and racial disparities. The crisis provides an opportunity for governments to experiment with radical policy shifts, such as a universal basic income or a Green New Deal. It may also turn the global tide against populism and soft-authoritarianism, as leaders like Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro demonstrate the pitfalls of ignoring scientific expertise in favor of nativism and tabloid conspiracy theories. However, the pandemic also provides a pretext to justify unprecedented intrusions into the daily lives of citizens, which can strengthen the hand of autocrats and further erode democratic institutions.Footnote 99

Third, COVID presents an opportunity for transformational change of the international order. The order was already under strain prior to 2020 with challenges from rising powers such as China and from retrenchment by traditional supporters like the United States and the United Kingdom. The liberal international order came to be associated with rising inequality and out-of-touch global elites.Footnote 100 The COVID crisis highlighted the dangers of both US disengagement and Chinese influence over the WHO. The international order is in urgent need of reform to strengthen crisis surveillance, prevention, and response.Footnote 101 This time, the system did not work: it needs reform.Footnote 102

Transformation of Political Science

Political scientists can and should be providing guidance as policymakers navigate major crises like COVID-19. However, there are several features of contemporary political science that create a gap between research and government policymaking. The gap highlighted most starkly by COVID-19 is the outdated publication process. In the natural sciences and medicine, peer review often takes a matter of weeks. As of this writing in July 2020, there are already numerous published articles about COVID-19 in top journals such as The Lancet and Nature, which have attracted hundreds of citations. In contrast, it is rare for peer-reviewed political science articles to reach publication within a year of submission. Policy debates are dominated by outlets like Foreign Affairs and Foreign Policy, which are not ideal venues for much of the research taking place in the field. Although blogs like The Monkey Cage and Duck of Minerva help, the discipline needs to develop more avenues to rapidly review and disseminate research findings, particularly in times of crisis that maximize potential impact on long-term policy outcomes.

There is also an unhelpful divide in the field between scholars who engage in academic research that gets published in top journals and scholars who engage with policymakers.Footnote 103 Faculty who return from government work often get relegated to second-class citizen status within their departments. There is an analogous problem in area studies: area expertise, with the arbitrary exception of American politics, is often treated dismissively even though area experts often have direct relationships with policymakers in the countries they study. Political science can have greater policy impact by drawing on the numerous policy connections that already exist within the field.

Political scientists should be better prepared to present and advocate for policy prescriptions during transformational crises.Footnote 104 How should institutions be reconfigured for effective crisis response? How should political leaders communicate with their citizens during a crisis? How should fiscal stimulus packages be targeted to promote transformation consistent with broader goals such as inclusive growth and climate change mitigation? These are all questions political science can speak to directly. The more urgent question is, can political scientists speak to policymakers? The field needs to develop better mechanisms to communicate our research and insert our prescriptions into policymaking processes during critical junctures.

Acknowledgments

For their helpful feedback, I thank Daniel Drezner, Tanisha Fazal, Martha Finnemore, Michael Horowitz, Tana Johnson, Kathleen McNamara, Abraham Newman, Louis Pauly, Kenneth Schultz, Beth Simmons, David Stasavage, and Erik Voeten. Nicholas Fraser provided excellent research assistance. I also thank Perry World House at the University of Pennsylvania and the editorial team of International Organization for organizing the virtual workshop on June 29-July 1, 2020 at which an earlier version of this article was presented.