No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

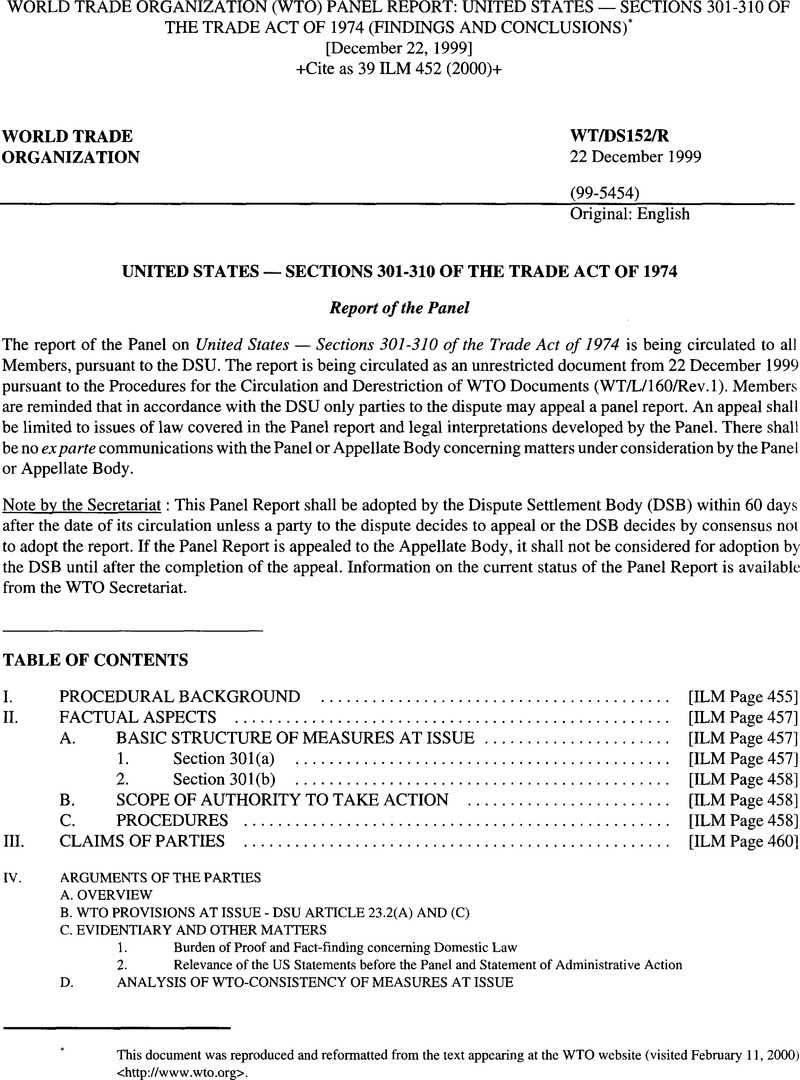

This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the WTO website (visited February 11, 2000) <http://www.wto.org>.

1 The original text of the Sections 301-310 is attached hereto as Annex I.

2 Section 301(a)(l), 19 U.S.C. § 241 l(a)(l).

3 Section 304(a)(l), 19 U.S.C. § 24i4(a)(l).

4 Section 301(a), 19 U.S.C. § 241 l(a).

5 Section 301(a)(2)(A), 19 U.S.C. § 2411(a)(2)(A).

6 The European Communities notes that the USTR terminated on this basis the original Section 301 investigation concerning the EC banana regime. (See Federal Register, Vol. 63, No. 204, October 22 1998, page 56688).

7 Section 301(a)(2)(B)(ii)(I), 19 U.S.C. § 2411(a)(l)(B)(ii)(I).

8 Section 301(a)(2)(B)(ii)(II), 19 U.S.C. § 2411(a)(l)(B)(ii)(II).

9 Section 301(a)(2)(B)(iii), 19 U.S.C. § 2411(a)(l)(B)(iii).

10 Section 301(a)(2)(B)(iv), 19 U.S.C. § 2411(a)(l)(B)(iv).

11 Section 301(a)(2)(B)(v), 19 U.S.C. § 2411(a)(l)(B)(v).

12 Section 301(a)(3), 19 U.S.C. § 241 l(a)(3).

13 Section 301(b), 19 U.S.C. § 241 l(b).

14 Section 301(d)(3)(B), 19 U.S.C. § 2411(d)(3)(B).

15 Section 301(d)(5), 19 U.S.C. § 241 l(d)(5).

16 Section 301(b), 19 U.S.C. § 241 l(b).

17 Section 301(c), 19 U.S.C. § 241 l(c).

18 Section 302(a)(2), 19 U.S.C. § 2412(a)(2).

19 Section 302(b), 19 U.S.C. § 2412(b).

20 See 19 U.S.C. § 2171(a), (b)(l) (1998).

21 See 19 U.S.C. § 2171(c)(l) (1998); Reorg. Plan No. 3 of 1979, 44 Fed. Reg. 69273 (1979); 19 C.F.R. § 2001.3(a) (1998).

22 Section 302(a)(2), 19 U.S.C. § 2412(a)(2).

23 Section 303(a)(l), 19 U.S.C. § 2413(a)(l).

24 Section 303(a)(2), 19 U.S.C. § 2413(a)(2).

25 Section 304(a)(2), 19 U.S.C. § 2414(a)(2).

26 Section 304(a)(l)(A), 19 U.S.C. § 2414(a)(l)(A).

27 Section 304(a)(l)(B), 19 U.S.C. § 2414(a)(l)(B).

28 Section 306(a), 19 U.S.C. § 2416(a).

29 Section 306(b), 19 U.S.C. § 2416(b).

30 Section 305(a)(l), 19 U.S.C. § 2415(a)(l).

31 Section 305(a)(2)(A), 19 U.S.C. § 2415(a)(2)(A).

629 See paras. 4.196-4.214, 4.233-4.244, 4.250-4.263 and 4.295-4.299 of this Report.

630 See Section V of this Report. Four third parties expressed no opinion in respect of this dispute.

631 Hereafter we refer to the “covered agreements” as those WTO agreements at issue in this dispute.

632 Answering Panel Question 43, the EC explicitly confirmed these limitations on the claims before us. See para. 4.634 of this Report.

633 Appellate Body Report on India - Patent Protection for Pharmaceutical and Agricultural Chemical Products (“India -Patents (US)“), WT/DS50/AB/R (complaint by US), adopted 16 January 1998, para. 66.

634 Ibid.

635 In this respect, the International Court of Justice (“ICJ“), referring to an earlier judgment by the Permanent Court of International Justice (“PCIJ“) noted the following: “Where the determination of a question of municipal law is essential to the Court's decision in a case, the Court will have to weigh the jurisprudence of the municipal courts, and ‘If this is uncertain or divided, it will rest with the Court to select the interpretation which it considers most in conformity with the law’ (Brazilian Loans, PCIJ, Series A, Nos. 20/21, p. 124)” (Elettronica Sicula S.p.A. (ELSI), Judgment, ICJ Reports 1989, p. 47, para. 62).

636 See footnote 657 and para. 7.146 below.

637 Articles 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention read as follows

1. A treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose.

2. The context for the purpose of the interpretation of a treaty shall comprise, in addition to the text, including its preamble and annexes: (a) any agreement relating to the treaty which was made between all the parties in connexion with the conclusion of the treaty; (b) any instrument which was made by one or more parties in connexion with the conclusion of the treaty and accepted by the other parties as an instrument related to the treaty.

3. There shall be taken into account together with the context: (a) any subsequent agreement between the parties regarding the interpretation of the treaty or the application of its provisions; (b) any subsequent practice in the application of the treaty which establishes the agreement of the parties regarding its interpretation; (c) any relevant rules of international law applicable in the relations between the parties.

4. A special meaning shall be given to a term if it is established that the parties so intended. Recourse may be had to supplementary means of interpretation, including the preparatory work of the treaty and the circumstances of its conclusion, in order to confirm the meaning resulting from the application of article 31, or to determine the meaning when the interpretation according to article 31: (a) leaves the meaning ambiguous or obscure; or (b) leads to a result which is manifestly absurd or unreasonable”.

638 As noted by the International Law Commission (ILC) - the original drafter of Article 31 of the Vienna Convention - in its commentary to that provision:

“The Commission, by heading the article ‘General Rule of Interpretation’ in the singular and by underlining the connexion between paragraphs 1 and 2 and again between paragraph 3 and the two previous paragraphs, intended to indicate that the application of the means of interpretation in the article would be a single combined operation. All the various elements, as they were present in any given case, would be thrown into the crucible and their interaction would give the legally relevant interpretation. Thus [Article 31] is entitled ‘General rule of interpretation’ in the singular, not ‘General rules’ in the plural, because the Commission desired to emphasize that the process of interpretation is a unity and that the provisions of the article form a single, closely integrated rule” (Yearbook of the ILC, 1966, Vol. II, pp. 219-220). See also, Sinclair, I., The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 2nd Edition, Manchester University Press, 1984, p. 116: “Every text, however clear on its face, requires to be scrutinised in its context and in the light of the object and purpose which it is designed to serve. The conclusion which may be reached after such a scrutiny is, in most instances, that the clear meaning which originally presented itself is the correct one, but this should not be used to disguise the fact that what is involved is a process of interpretation”.

639 Appellate Body report on Japan - Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages (“Japan - Alcoholic Beverages“), WTVDS8/AB/R, adopted 1 November 1996, pp. 11-12.

640 Article XVI:4 provides as follows: “Each Member shall ensure the conformity of its laws, regulations and administrative procedures with its obligations as provided in the annexed Agreements”.

641 The meaning of the term “laws” in Article XVI:4 of the WTO Agreement must accommodate the very broad diversity of legal systems of WTO Members. For present purposes, we are of the view that the term “laws” is wide enough to encapsulate as one single measure the multi-layered Sections 301-310. In the alternative - i.e. in case the term “laws” should be said to cover statutory language only - we would consider the non-statutory elements of Sections 301-310 that are of an institutional or administrative nature to fall under the terms “regulations and administrative procedures” also referred to in Article XVI:4. Under this alternative approach as well, we would view it necessary - given the special nature of the national law in question - to examine all elements under Sections 301-310 as one measure in order to correctly assess its overall conformity with WTO rules.

642 Similarly, the Appellate Body in US - Import Prohibition of Ceratin Shrimp and Shrimp Products (“US - Shrimp”, WT/DS58/AB/R, adopted 6 November 1998, at paras. 160 and 186) first examined the US measure itself and found that it was provisionally justified under Article XX(g) of GATT 1994. However, it then found that the application of that very same measure, pursuant to administrative guidelines and practice, constituted an abuse or misuse of the provisional justification made available by Article XX(g) in the light of the chapeau of Article XX. On these grounds it concluded that the US measure read in this sense was in violation of GATT 1994.

643 For purposes of this dispute, we assume that the 18 months time-limit is the earlier of the two time-limits mentioned in Section 304, i.e. falls before the lapse of “30 days after the date on which the dispute settlement procedure is concluded”.

644 The US agrees that it cannot postpone the making of this determination. In respect of Japan - Measures Affecting Agricultural Products (“Japan -Agricultural Products“), adopted 19 March 1999, WT/DS76/AB/R and India - Patents (US), for example, the US - answering Panel Question 24(a) (as reflected in para. 4.586 of this Report) - stated that “the United States did not make formal Section 304 determinations by the 18-month anniversary, but should have” (emphasis added).

645 Article 4.7 of the DSU, for example, provides for a minimum period of 60 days for consultations, unless there is agreement to the contrary or urgency in accordance with Article 4.8.

646 Article 12.8 refers to six months “as a general rule” for the timeframe between panel composition and issuance of the final report to the parties. Article 12.9 provides that “[i]n no case should the period from the establishment of the panel to the circulation of the report to the Members exceed nine months” (emphasis added). Article 17.5 states that “[a]s a general rule, the proceedings [of the Appellate Body] shall not exceed 60 days”. It adds, however, that “[i]n no case shall the proceedings exceed 90 days”. However, even this seemingly compulsory deadline has been passed in three cases so far (United States - Restrictions on Imports of Cotton and Man-Made Fibre Underwear, WT/DS24/AB/R, 91 days; European Communities - Measures Concerning Meat and Meat Products (Hormones) (“EC - Hormones“), WT/DS26/AB/R and DS48/AB/R, 114 days; and US - Shrimp, op. cit., 91 days). Finally, Article 20 refers to 9 months - 12 months in case of an appeal - “as a general rule” for the period between panel establishment and adoption of report(s) by the DSB.

647 When we refer hereafter to the exhaustion of DSU proceedings, we mean the date of adoption by the DSB of panel and, as the case may be, Appellate Body reports on the matter.

648 In 17 cases out of the 26 cases which so far led to DSB recommendations, more than 18 months lapsed between the request for consultations and the adoption of reports. Eleven of these 17 cases were brought by the US either as the sole complainant or a cocomplainant: European Communities - Regime for the Importation, Sale and Distribution of Bananas (“EC - Bananas III”, WT/DS27), EC - Hormones (op. cit.), Japan - Measures Affecting Consumer Photographic Film and Paper (WT/DS44), India - Patents (US) (op. cit.), European Communities/United Kingdom/Ireland - Customs Classification of Certain Computer Equipment (WT/DS62, 67 and 68), Indonesia - Certain Measures Affecting the Automobile Industry (WT/DS54, 55, 59 and 64), Japan - Agricultural Products (op. cit.), Korea - Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages (WT/DS75 and 84), Australia - Subsidies Provided to Producers and Exporters of Automobile Leather (WT/DS106), India - Quantitative Restrictions on Imports of Agricultural, Textile and Industrial Products (WT/DS90) and Canada - Measures Affecting the Importation of Milk and the Exportation of Dairy Products (WT/DS103, US complaint and WT/DS113, complaint by New Zealand). The six other cases were: US - Shrimp (op. cit.), Australia - Measures Affecting the Importation of Salmon (WT/DS18), Guatemala - Anti-Dumping Investigation Regarding Portland Cement from Mexico (WT/DS60), US-Anti-Dumping Duty on Dynamic Random Access Memory Semiconductors (DRAMS) of one Megabit or above from Korea (WT/DS99), Brazil - Export Financing Programme for Aircraft (WT/DS46) and Canada - Measures Affecting the Export of Civilian Aircraft (“Canada - Aircraft”, WT/DS70).

649 The US argued in its second submission that the USTR is precluded from making such a determination of inconsistency. To the extent this US argument is based on the statutory language of Section 304 alone, we reject the argument for the reasons given in this Report.

650 Section 304(a) refers to WTO “proceedings, if applicable” as a basis of the determination to be made. This statutory language is not sufficiently precise to construe it as curtailing the USTR's discretion to make a determination of inconsistency before the adoption of findings by the DSB. The reference to “proceedings” as a basis for the determination allows WTO proceedings to be taken into account but does not, in our view, preclude a determination of inconsistency before the final outcome of WTO proceedings, i.e. before the adoption of DSB recommendations. We note that whereas the first time-limit under Section 304(a)(2) explicitly refers to the conclusion of dispute settlement procedures (“30 days after the date on which the dispute settlement procedure is concluded“), the second time-limit does not refer to any proceedings, let alone to the completion of WTO proceedings (“18 months after the date on which the investigation is initiated“). Section 304(a)(2) mandates the making of a determination “the earlier of” these two timelimits. We note, finally, that the US itself had first argued that Section 304 does not “compel” the making of a determination of inconsistency which seems to imply that although not compelled, the USTR is permitted to make such a determination. Only in its second submission did the US argue that the USTR is actually “precluded” from making such determination.

651 See, for example, Panel Reports on United States Taxes on Petroleum and Certain Imported Substances (“US Superfund“), adopted 17 June 1987, BISD 34S/136, para. 5.2.2 (where the legislation imposing the tax discrimination only had to be applied by the tax authorities at the end of the year after the panel examined the matter) and United States Measures Affecting Alcoholic and Malt Beverages (“US Malt Beverages“), adopted 19 June 1992, BISD 39S/206, paras. 5.39, 5.57, 5.60 and 5.66 (where the legislation imposing the discrimination was, for example, not being enforced by the authorities). See also Panel Reports on EEC Regulation on Imports of Parts and Components (“EEC Parts and Components“), adopted 16 May 1990, BISD 37S/132, paras. 5.25-5.26, Thailand Restrictions on Importation of and Internal Taxes on Cigarettes (“Thai Cigarettes“), adopted 7 November 1990, BISD 37S/200, para. 84 and United States Measures Affecting the Importation, Internal Sale and Use of Tobacco (“US Tobacco“), adopted 4 October 1994, BISD 41S/131, para. 118.

652 Article XVI:4 goes a step further than Article 27 of the Vienna Convention. Article 27 of the Vienna Convention provides that” [a] party may not invoke the provisions of its internal law as justification for its failure to perform a treaty”. Article XVI:4, in contrast, not only precludes pleading conflicting internal law as a justification for WTO inconsistencies, but requires WTO Members actually to ensure the conformity of internal law with its WTO obligations.

653 Panel Reports on Argentina Measures Affecting Imports of Footwear, Textiles, Apparel and Other Items (“Argentina Textiles and Apparel (US)“), WT/DS56/R (complaint by US), adopted 22 April 1998, paras. 6.45-47 (see also Appellate Body Report, WT/DS56/AB/R, paras. 48-55); Canada Aircraft, op. cit., paras. 9.124 and 9.208, Turkey Restrictions on Imports of Textile and Clothing Products, WT/DS34/R, circulated to Members on 31 May 1999 (appealed on other grounds), para. 9.37.

654 Article 23.2(a), in contrast, prohibiting Members from making certain determinations, is not covered elsewhere in the DSU.

655 One could refer, for example, to the requirement to request consultations pursuant to Article 4 of the DSU before requesting a panel under Article 6.

656 Not notifying mutually agreed solutions to the DSB as required in Article 3.6 of the DSU or not abiding by the requirements for a request for consultations or a panel as elaborated in Articles 4 and 6 are some other examples of conduct that would be contrary to DSU rules and procedures but is not mentioned specifically in Article 23.2.

657 We consider that if the USTR were to exercise, in a specific dispute, the right reserved to him or her under the statutory language of Section 304 to make a determination of inconsistency before exhaustion of DSU procedures, the US conduct would meet the different elements required for a breach of Article 23.2(a) in a specific instance. This conclusion is of crucial importance since it shows that the statutory language of Section 304 reserves the right to the USTR to breach at least the first type of obligations in Article 23.2(a) in a specific instance. Four elements must be satisfied for a specific act in a particular dispute to breach Article 23.2(a):

(a) the act is taken “in such cases” (chapeau of Article 23.2), i.e. in a situation where a Member “seek[s] the redress of a violation of obligations or other nullification or impairment of benefits under the covered agreements or an impediment to the attainment of any objective of the covered agreements”, as referred to in Article 23.1; (b) the act constitutes a “determination“; (c) the “determination” is one “to the effect that a violation has occurred, that benefits have been nullified or impaired or that the attainment of any objective of the covered agreements has been impeded“; (d) the “determination” is either not made “through recourse to dispute settlement in accordance with the rules and procedures of [the DSU]” or not made “consistent with the findings contained in the panel or Appellate Body report adopted by the DSB or an arbitration award rendered under [the DSU]”. The two elements of this requirement are cumulative in nature. Determinations are only allowed when made through recourse to the DSU and consistent with findings adopted by the DSB or an arbitration award under the DSU. Applying these four elements to the specific determination allowed under the statutory language of Section 304, namely a determination of inconsistency before exhaustion of DSU procedures we note, first, the parties’ agreement that all Section 304 determinations are made in cases where the US is seeking the redress of WTO inconsistencies, in the sense of the first element outlined above. We agree. Obviously, when pursuing a matter of US rights under the WTO through Section 302 investigations, WTO consultations and procedures, and making a decision on whether US rights under the WTO are being denied under Section 304, the US is seeking redress of what it considers to be WTO inconsistencies. Both parties also agree that determinations under Section 304 meet the second of the four elements, a determination in the sense of Article 23.2(a). We agree. Some of the relevant dictionary meanings of the word “determination” in the context of Article 23.2(a) are: “the settlement of a suit or controversy by the authoritative decision of a judge or arbiter; a settlement or decision so made, an authoritative opinion … the action of coming to a decision; the result of this; a fixed intention” (The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, Ed. Brown, L., Clarendon Press, Oxford, Vol. 1, p. 651). Without there being a need precisely to define what a “determination” in the sense of Article 23.2(a) is, we consider that given its ordinary meaning a “determination” implies a high degree of firmness or immutability, i.e. a more or less final decision by a Member in respect of the WTO consistency of a measure taken by another Member. Given that Article 23.2(a) only deals with “determinations” in case a Member is seeking redress of WTO inconsistencies, we are of the view that a “determination” can only occur subsequent to a Member having decided that, in its preliminary view, there may be a WTO inconsistency, i.e. only once that Member has decided to seek redress of such inconsistency. Mere opinions or views expressed before that stage is reached, are not intended to be covered by Article 23.2(a). However, once a Member does bring a case under the DSU, in particular once it requests the establishment of a panel, one can assume that this preliminary stage has been passed and the threshold of a “determination” met. Such reading of the term “determination” is confirmed by the exception provided for “determinations” made “through recourse to dispute settlement in accordance with” the DSU, an exception that explicitly allows for the “determination” implicit in pursuing a case before a panel. In any event, what is decisive under Article 23.2(a) is not so much whether an act constitutes a “determination” in our view, a more or less formal requirement that needs broad reading but whether it is consistent with DSU rules and procedures, the fourth element discussed below. On that basis, we find that USTR determinations under Section 304 made subsequent to internal investigations, WTO consultations and proceedings, if applicable; and, in the case of determinations of inconsistency, automatically and as a conditio sine qua non leading to a decision on action under Section 301 meet the threshold of firmness and immutability required for a “determination” under Article 23.2(a). The third element under Article 23.2(a) as applied to the specific determination under examination is also satisfied. We recall that this determination would be one finding that US rights under the WTO have been denied, i.e. a determination “to the effect that a violation has occurred, that benefits have been nullified or impaired or that the attainment of any objective of the covered agreements has been impeded”, thus meeting the third element under Article 23.2(a). The fourth element under Article 23.2(a) is likewise satisfied. We recall that the specific determination under examination here would be one made before DSB findings on the matter have been adopted. It would thus not be made “through recourse to dispute settlement in accordance with the rules and procedures of [the DSU]” nor made “consistent with the findings contained in the panel or Appellate Body report adopted by the DSB”. Indeed, such determination made before exhaustion of DSU procedures, would not be required, referred to or relevant for any of the steps or procedures in the DSU. On the contrary, it would be a determination that, at face value, prejudices and could even contradict the outcome of DSU procedures. Moreover, any such determination could not be consistent with DSB findings, since no such findings would, as yet, be adopted. In conclusion, if the USTR were to exercise, in a specific dispute, the right reserved for it in Section 304 to make a determination of inconsistency before exhaustion of DSU procedures, the US conduct would meet all four elements required for a breach of Article 23.2(a).

658 Imagine, for example, legislation providing that all imports, including those from WTO Members, would be subjected to a customs inspection and that the administration would enjoy the right, at its discretion, to impose on all such goods tariffs in excess of those allowed under the schedule of tariff concessions of the Member concerned. Would the fact that under such legislation the national administration would not be mandated to impose tariffs in excess of the WTO obligation, in and of itself exonerate the legislation in question? Would such a conclusion not depend on a careful examination of the obligations contained in specific WTO provisions, say, Article II of GATT and specific schedule of concessions?

659 See paras. 4.173 ff. and 7.51 of this Report.

660 We reject the notion that mis danger is removed by virtue of the international obligation alone. Even in the EC where EC norms may produce direct effect and thus give far greater assurance, an EC Member State is not absolved by this fact from its duty to bring national legislation into compliance with its transnational obligations under, say, an EC directive (Commission v. Belgium, Case 102/79, [1980] European Court Reports 1473 at para. 12 of the judgment).

661 We make this statement as a matter of fact, without implying any judgment on the issue. We note that whether there are circumstances where obligations in any of the WTO agreements addressed to Members would create rights for individuals which national courts must protect, remains an open question, in particular in respect of obligations following the exhaustion of DSU procedures in a specific dispute (see Eeckhout, P., The Domestic Legal Status of the WTO Agreement: Interconnecting Legal Systems, Common Market Law Review, 1997, p. 11; Berkey, J., The European Court of Justice and Direct Effect for the GATT: A Question Worth Revisiting, European Journal of International Law, 1998, p. 626). The fact that WTO institutions have not to date construed any obligations as producing direct effect does not necessarily preclude that in the legal system of any given Member, following internal constitutional principles, some obligations will be found to give rights to individuals. Our statement of fact does not prejudge any decisions by national courts on this issue.

662 See also similar language in the second preambles to GATT 1947 and GATS. The TRIPS Agreement addresses even more explicitly the interests of individual operators, obligating WTO Members to protect the intellectual property rights of nationals of all other WTO Members. Creating market conditions so that the activity of economic operators can flourish is also reflected in the object of many WTO agreements, for example, in the non-discrimination principles in GATT, GATS and TRIPS and the market access provisions in both GATT and GATS.

663 The importance of security and predictability as an object and purpose of the WTO has been recognized as well in many panel and Appellate Body reports. See the Appellate Body report on Japan Alcoholic Beverages, op. cit., p. 31 (“WTO rules are reliable, comprehensible and enforceable. WTO rules are not so rigid or so inflexible as not to leave room for reasoned judgements in confronting the endless and ever-changing ebb and flow of real facts in real cases in the real world. They will serve the multilateral trading system best if they are interpreted with that in mind. In that way, we will achieve the ‘security and predictability’ sought for the multilateral trading system by the Members of the WTO through the establishment of the dispute settlement system“). It has also been referred to under the TRIPS Agreement. In the Appellate Body Report on India Patents (US), op. cit., it was found, at para. 58, that “India is obliged, by Article 70.8(a), to provide a legal mechanism for the filing of mailbox applications that provides a sound legal basis to preserve both the novelty of the inventions and the priority of the applications as of the relevant filing and priority dates” (italics added). See also the WTO Panel Report on Argentina Textiles and Apparel (US), op. cit., para. 6.29 and the GATT Panel Reports on United States Manufacturing Clause, adopted 15/16 May 1984, BISD 31S/74, para. 39; Japan Measures on Imports of Leather (“Japan Leather“), adopted 15/16 May 1984, BISD 31S/94, para. 55; EEC Imports of Newsprint, adopted November 20 1984, BISD 31S/114, para. 52; Norway Restrictions on Imports of Apples and Pears, adopted 22 June 1989, BISD 36S/306, para. 5.6.

664 See Article 27 of the Vienna Convention.

665 A change in the relative competitive opportunities caused by a measure of general application as such, to the detriment of imported products and in favour of domestically produced products, is the decisive criterion.

666 In the Panel Report on US Superfund (op. cit., paras. 5.2.1 and 5.2.2) tax legislation as such was found to violate GATT obligations even though the legislation had not yet entered into effect. See also the Panel Report on US Malt Beverages (op. cit., paras. 5.39, 5.57, 5.60 and 5.69) where the legislation imposing the tax discrimination was, for example, not being enforced by the authorities.

667 See Panel Report on US Tobacco, op. cit., para. 96:

“The Panel noted that an internal regulation which merely exposed imported products to a risk of discrimination had previously been recognized by a GATT panel to constitute, by itself, a form of discrimination, and therefore less favourable treatment within the meaning of Article III. The Panel agreed with this analysis of risk of discrimination as enunciated by this earlier panel”. A footnote to this paragraph refers to the Panel Report on EEC Payments and Subsidies Paid to Processors and Producers of Oilseeds and Related Animal Feed Protein, adopted 25 January 1990, BISD 37S/86, para. 141, which reads as follows: “Having made this finding the Panel examined whether a purchase regulation which does not necessarily discriminate against imported products but is capable of doing so is consistent with Article 111:4. The Panel noted that the exposure of a particular imported product to a risk of discrimination constitutes, by itself, a form of discrimination. The Panel therefore concluded that purchase regulations creating such a risk must be considered to be according less favourable treatment within the meaning of Article 111:4. The Panel found for these reasons that the payments to processors of Community oilseeds are inconsistent with Article 111:4”.

668 Op. cit., paras. 6.45-6.47, in particular para. 6.46: “In the present dispute we consider that the competitive relationship of the parties was changed unilaterally by Argentina because its mandatory measure clearly has the potential to violate its bindings, thus undermining the security and the predictability of the WTO system” (emphasis added). This was confirmed by the Appellate Body (op. cit., para. 53): “In the light of this analysis, we may generalize that under the Argentine system, whether the amount of the DIEM [a regime of Minimum Specific Import Duties] is determined by applying 35 per cent, or a rate less than 35 per cent, to the representative international price, there will remain the possibility of a price that is sufficiently low to produce an ad valorem equivalent of the DIEM that is greater than 35 per cent. In other words, the structure and design of the Argentine system is such that for any DIEM, no matter what ad valorem rate is used as the multiplier of the representative international price, the possibility remains that there is a “break-even” price below which the ad valorem equivalent of the customs duty collected is in excess of the bound ad valorem rate of 35 per cent”. On that basis, the Appellate Body found that the application of a type of duty different from the type provided for in a Member's Schedule is inconsistent with Article II: 1(b), first sentence, of the GATT 1994. In this respect, see also the Panel Report on United States Standards for Reformulated and Conventional Gasoline, adopted 20 May 1996, WT/DS2/R, para. 6.10.

669 Op. cit., para. 5.2.2.

670 Panel Report on Japan Leather, op. cit., para. 55. In this respect, see also Panel Report on US Malt Beverages (op. cit., para. 5.60), where legislation was found to constitute a GATT violation even though it was not being enforced, for the following reason:

“Even if Massachusetts may not currently be using its police powers to enforce this mandatory legislation, the measure continues to be mandatory legislation which may influence the decisions of economic operators. Hence, a non-enforcement of a mandatory law in respect of imported products does not ensure that imported beer and wine are not treated less favourably than like domestic products to which the law does not apply” (emphasis added).

671 As a result, we do not consider that the general statements made in certain GATT panels are correct in respect of all WTO obligations and in all circumstances, for example, the statement in Panel Report on EEC Parts and Components (op. cit., para. 5.25) that “[u]nder the provisions of the [GATT] which Japan claims have been violated by the EEC contracting parties are to avoid certain measures; but these provisions do not establish the obligation to avoid legislation under which the executive authorities may possibly impose such measures” and in Panel Report on Thai Cigarettes (op. cit., para. 84), the statement that “legislation merely giving the executive the possibility to act inconsistently with Article 111:2 [of GATT] could not, by itself, constitute a violation of thai provision”. In respect of this ambivalence in GATT jurisprudence, see Chua, A., Precedent and Principles of WTO Panel Jurisprudence, Berkeley Journal of International Law, 1998, p. 171, in particular at p. 193.

672 In this respect, see the statements made by third parties to this dispute in Section V of our Report.

673 We realise that the possibility for a Member to breach its obligations under Article 23.2(a) will always remain. In that sense, guarantees can never be completely assured. However, remote possibilities that obligations may be breached, i.e. normal risks to be accepted in all trade relations, should be distinguished from explicit risks or threats created by statute, i.e. where a Member makes it known to all its trade partners that they may be subjected to an internal procedure under which the right to breach WTO obligations is reserved.

674 Since an examination of the elements referred to in Article 31 does not leave the meaning of Article 23.2(a) “ambiguous or obscure“ nor leads to a result which is “manifestly absurd or unreasonable” in the sense of Article 32 of the Vienna Convention, we do nol need to evaluate the supplementary means of interpretation referred to in Article 32.

675 We would like to emphasize again that this finding does not require the wholesale reversing of earlier GATT and WTO jurisprudence on mandatory and discretionary legislation. The classical test under previous jurisprudence was that only legislation mandating a WTO inconsistency or precluding WTO consistency, could, as such, violate WTO provisions (see paras. 4.173 ff. and 7.51 of this Report). The methodology we adopted was to examine first and with care the WTO provision in question and the obligation it imposed on Members. It could not be presumed, in our view, that the WTO would never prohibit legislation under which a national administration would enjoy certain discretionary powers. If it were found upon such examination that certain discretionary powers were in fact inconsistent with a WTO obligation, then legislation allowing such discretion would, on its face, fail the classical test: it would preclude WTO consistency.

676 See paras. 7.25-7.28 of this Report.

677 On this issue, the statutory language is, however, conclusive in that, as we found in para. 7.31(a), the USTR is obligated to make a determination within the 18 months time-frame under Section 304.

678 Appellate Body Report on India Patents (US), op. cit., paras. 69-71.

679 Section 304 states that the determination is to be based on “the investigation initiated under section 302 … and the consultations (and proceedings, if applicable) under section 303” (emphasis added). See, in this respect, footnote 649 above.

680 As the US noted in its answer to Panel Question 32(b), “[t]here is nothing in the text of Sections 301-310 which prevents [the USTR from making two determinations in one and the same case]… While the Trade Representative is required to make a determination within the time frames set forth in that section, nothing prevents her from making additional determinations after that time”. See para. 4.599 above.

681 We reach this conclusion not least because of the US constitutional principle of construing US domestic law, where possible, in a way that is consistent with US obligations under international law. We accept the US submissions that “[i]n U.S. law, it is an elementary principle of statutory construction that ‘an act of Congress ought never to be construed to violate the law of nations if any other possible construction remains'. Murray v. Schooner Charming Betsy, 6 U.S. (2 Cranch) 64,118 (1804). While international obligations cannot override inconsistent requirements of domestic law, ‘ambiguous statutory provisions … [should] be construed, where possible, to be consistent with international obligations of the United States'. Footwear Distributors and Retailers of America v. United States, 852 F. Supp. 1078, 1088 (CIT), appeal dismissed, 43 F.3d 1486 (Table) (Fed. Cir. 1994), citing DeBartolo Corp. v. Florida Gulf Coast Building and Trades Council, 485 U.S. 568 (1988)”.

682 The SAA, as is often the case in trade policy and trade law circles, uses “section 301” as a generic term referring to enforcement procedures under Sections 301-310 more generally. Thus, when referring to “section 301 determinations”, we understand this to mean any determination made under Sections 301-310.

683 The US, in its answer to Panel Question 25 (as reflected in paras. 4.121 and 4.534 of this Report), unambiguously confirmed this construction. It noted in particular that “[t]he SAA must, by law, be treated as the authoritative expression concerning the interpretation of the statute in any judicial proceedings” and that with reference to all elements under Section 304 “under U.S. law, it is required to base an affirmative determination that U.S. WTO agreement rights have been denied on adopted panel and Appellate Body findings. That is to say, U.S. law precludes such an affirmative determination not based on adopted panel or Appellate Body findings”.

684 Of course, it is easier to change administrative decisions than it is to change legislation. However, as noted in para. 7.133, in the event the US administration were to repeal its undertaking in respect of US domestic law, it would not only go against express expectations held by Congress set out in the SAA. The US would also expose itself to a finding of inconsistency with its WTO obligations.

685 SAA, p. 1.

686 SAA, pp. 365-366.

687 In this respect, the EC refers to Section 102(a) of the US Uruguay Round Agreements Act 1994, the Act by which the US Congress approved the WTO Agreement. Section 102(a) of this Act provides “(1) UNITED STATES LAW TO PREVAIL IN CONFLICT. No provision in any of the Uruguay Round Agreements, nor the application of any such provision to any person or circumstance, that is inconsistent with any law of the United States shall have effect. (2) CONSTRUCTION. - Nothing in this Act shall be construed … (B) to limit any authority conferred under any law of the United States, including section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 unless specifically provided for in this Act”. We note, however, that even if one were to hold that, pursuant to Section 102(a), the WTO agreements and the Uruguay Round Act itself could not, and did not, curtail the USTR's discretion under Section 304, in our view, the US Administration itself could do so, and did so, inter alia, in the SAA. It did so validly by means of exercising discretion granted to it under the statutory language of Section 304.

688 SAA, pp. 366-367:

“There is no basis for concern that the Uruguay Round agreements in general, or the DSU in particular, will make future Administrations more reluctant to apply section 301 sanctions that may be inconsistent with U.S. trade obligations because such sanctions could engender DSU-aufhorized counter-retaliation. Although in specific cases the United States has expressed its intention to address an unfair foreign practice by taking action under section 301 that has not been authorized by the GATT, the United States has done so infrequently. In certain cases, the United States has taken such action because a foreign government has blocked adoption of a GATT panel report against it. Just as the United States may now choose to take section 301 actions that are not GATT authorized, governments that are the subject of such actions may choose to respond in kind. That situation will not change under the Uruguay Round agreements. The risk of counter-retaliation under the GATT has not prevented the United States from taking action in connection with such matters as semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, beer, and hormone-treated beef. It may be possible to construe these two paragraphs in the SAA as in fact indicating that the conditions which explain an abusive use of Section 301 in the past in particular, the blocking of adoption of a panel report no longer prevail under the WTO see US Answer to Panel Question 38 reflected in paras. 4.134-4.140 of this Report). We decided to put the worst possible construction on these paragraphs in the SAA concluding that there is a tension between these paragraphs and the undertakings in the bullet points. As indicated in the body of the Report, this tension ought to be resolved following US constitutional law principles in favour of a construction which upholds compliance with international legal obligations. We were brought to that solution also when considering, in addition, the solemn undertakings of the US to the Panel confirming the Administration's view set out in the bullet points that in the light of the SAA the USTR is precluded from applying Sections 301-310 in a manner inconsistent with WTO obligations.

689 As noted earlier, the SAA is explicitly said to represent an authoritative expression “both for purposes of U.S. international obligations and domestic law”, see para. 7.110 of this Report.

690 SAA, p. 366.

691 See also footnote 683 above.

692 In the Nuclear Test case (Australia v. France), the ICJ held that France was legally bound by publicly given undertakings, made on behalf of the French Government, to cease the conduct of atmospheric nuclear tests. The criteria of obligation were: the intention of the state making the declaration that it should be bound according to its terms; and that the undertaking be given publicly: “It is well recognized that declarations made by way of unilateral acts, concerning legal or factual situations, may have the effect of creating legal obligations. Declarations of this kind may be, and often are, very specific. When it is the intention of the State making the declaration that it should become bound according to its terms, that intention confers on the declaration the character of a legal undertaking, the State being henceforth legally required to follow a course of conduct consistent with the declaration. An undertaking of this kind, if given publicly, and with an intent to be bound, even though not made within the context of international negotiations, is binding”. (ICJ Reports (1974), p. 253 at pp. 267-271, quoted above from para. 43; see also Nuclear Test case (New Zealand v. France), ICJ Reports (1974), p. 457, at pp. 472-475; Legal Status of Eastern Greenland case, PCIJ Reports, Series A/B, No. 53, where a statement was found to have legal effects even though it was not made publicly but in the course of conversations with the Norwegian Foreign Minister; Nicaragua case (Merits), ICJ Reports (1986), p. 14, at p. 132; Case Concerning the Frontier Dispute, ICJ Reports (1986), p. 554, at pp. 573-574 ). In this case, the legal effect of the US statements does not go as far as creating a new legal obligation. Nonetheless we have applied to them the same, and perhaps even more, stringent conditions. Subsequent to the Nuclear Test case, some authors criticised giving legal effect to declarations not directed to a specific State or States but expressed erga omnes ﹛see Rubin, A., The International Legal Effects of Unilateral Declarations, American Journal of International Law, 1977, p. 1 and Franck, T., Word Made Law: The Decision of the ICJ in the Nuclear Test Cases, American Journal of International Law, 1975, p. 612). In this case the US statements had explicit recipients and were made in the context of a specific dispute settlement procedure.

693 See paras. 7.110 and 7.114 of this Report.

694 In its first submission the US argued forcefully that Section 304 did not ever require the USTR to make a determination of inconsistency before exhaustion of DSU proceedings ﹛see paras. 4.527-4.530 of this Report). In its second submission the US went further and argued that the correct interpretation of Section 304 is that the USTR is legally precluded from making such determination ﹛see paras. 4.536-4.537 of this Report).

695 Below we also canvass another hypothesis, see para. 7.133 of this Report. In that alternative hypothesis the effect of the undertaking is actually to discharge State responsibility that the statutory language may have given rise to.

696 US oral statement, second meeting, para. 16 ﹛see para. 4.990).

697 This dispute is explained in paras. 5.273-274 of this Report. As a result of the US action in this respect, see also United States Imposition of Duties on Automobiles from Japan under Section 301 and 304 of the Trade Act of 1974 ﹛“Japan Auto Parts“), WT/DS6 (complaint by Japan), settlement notified to the DSB.

698 See documents under WT/DS165.

699 In Japan Auto Parts the US was not seeking redress of inconsistencies under the WTO, it was examining, inter alia, whether Japanese acts or policies in this respect were “unreasonable” under Section 301(b). We consider that even if conduct inconsistent with Article 23.2(a) occurred a matter on which we express no opinion the kind of inconsistency implicated would be outside our terms of reference since it covers issues not raised in the EC claims before us. Whether the US violated Article 23 in the Bananas III case is one of the claims subject to separate panel proceedings. Even if the US conduct in response to the alleged implementation of DSB findings by the EC was inconsistent with Article 23.2(a), we note that any determinations made by the US in this respect were made under Section 306 i.e. were determinations on whether implementation of DSB findings took place not under Section 304 at issue here, i.e. determinations on whether US rights are being denied prior to the issue of implementation arising. The fact that determinations under Section 306 have to be considered, for purposes of, e.g. publication and subsequent action under Section 301, as determinations under Section 304, pursuant to Section 306(b)(1), does not alter our conclusion. We deal with the EC claim of inconsistency of Section 306 in Section VII.D below. Finally, in Argentina Textiles and Apparel (US), the USTR determination was published subsequently to both the lapse of the 18 months time-period referred to in Section 304 and the adoption of DSB findings on the matter. The determination explicitly states that it is based on the findings of the DSB on the matter. We do not consider the fact that the determination was retroactively dated back to 3 April 1998, i.e. the day before the lapse of the 18 months time-period and thereby also a date prior to the adoption of DSB findings on the matter (22 April 1998), to be relevant on the international plane. In our view, when it comes to examining Article 23.2(a), the actual date of the determination and, especially, the basis of the determination's finding are the critical elements. In terms of US obligations to other WTO Members, this case shows that the US waited until the end of DSU procedures before it publicly announced its determination and that the USTR effectively based her findings on the result of the DSU process. The outcome of the DSU process conditioned the content of the USTR determination.

700 When we refer to the “US Government” in this Report we mean to include legislature, executive and judiciary.

701 See Section VII.B.6.

702 In this respect, see para. 7.20 and footnote 657 above.

703 Recalling the four elements required for there to be a breach of Article 23.2(a) in respect of specific acts taken in a given dispute, outlined above in footnote 657, we thus find that “considerations” under Section 306 are “determinations” in the sense of the second element under Article 23.2(a). We also find that determinations under Section 306 meet the first element under Article 23.2(a). The US is obviously seeking redress of WTO inconsistencies when it monitors the implementation of DSB findings under Section 306. The third element concerns the question as to whether the determination under Section 306 is one “to the effect that a violation has occurred … ”. Examining specifically the determination at issue here, the one statutorily reserved in Section 306, i.e. the determination that implementation did not take place, in other words, that implementing measures are not consistent with WTO rules even though Article 21.5 procedures have not yet been completed, we hold the view that such determination is one of inconsistency meeting the third element under Article 23.2(a).

704 See footnote 657 above.

705 See para. 7.50 and footnote 657.

706 As outlined in footnote 698, the determination statutorily reserved in Section 306 meets the first three elements for there to be a breach of Article 23.2(a) in a given dispute. The crucial question to be dealt with here remains, however, whether such determination also meets the fourth element under Article 23.2(a). In this respect see footnote 657.

707 As noted in the EC response to Panel question 23, “the EC has not requested this Panel to ‘make a decision on the relationship between Article 21.5 and 22’ of the DSU. Rather, the EC has requested the DSB and obtained the establishment of this Panel in order to make ‘such findings as will assist the DSB in making the recommendations or giving the rulings provided for in’ the provisions of the agreements cited in the WTO document WT/DS152/11 of 2 February 1999” (see para. 4.901 of this Report). We note that the EC added to its response that “the WTO consistency of Sections 301-310 must be assessed against all the provisions quoted in the Panel's terms of reference, including Article 21.5 of the DSU on its own” and that “[fjhe interpretation of Article 22 of the DSU is logically and legally a distinct issue to be addressed by the Panel separately, if necessary”. However, nowhere did the EC substantiate any specific claim of violation of Article 21.5 or Article 22. These provisions are only relevant in this case as elements for an assessment of the EC claims under Article 23. If such assessment does not require a decision on the relationship between Articles 21.5 and 22, we do not consider it necessary the word referred to by the EC nor within our mandate as set out in Section VILA of this Report, to solve this controversy.

708 See para. 7.151 of this Report.

709 In this respect, we note that in another dispute, Australia Subsidies Provided to Producers and Exporters of Automotive Leather (“Australia Leather”, WT/DS126/R, adopted 16 June 1999, not appealed), the US invoked Article 21.5 but agreed with the defending party, Australia, to await completion of Article 21.5 proceedings before requesting authorization to suspend concessions. With reference to footnote 6 to Article 4 of the SCM Agreement both parties agreed “that the deadline for DSB action under the firstsentence of Article 22.6 of the DSU shall be 60 days after the circulation of the review panel report under Article 21.5 of the DSU. and that the deadline specified in the third sentence of Article 22.6 of the DSU for completion of arbitration shall be 45 days after the matter is referred to arbitration” (WT/DS126/8, p. 2).

710 See Section VII.C.3 and 4.

711 See Section VII.C.6.

712 See para. 7.112, second bullet point, paras. 7.114 ff. as well as footnotes 680 and 681.

713 In this respect, we recall that we found earlier that the statutory language of Section 306 allows the USTR to await the completion of DSU procedures, including Article 21.5 procedures, before making a determination of inconsistency under Section 306 (see para. 7.146 above). As to the lawfulness of taking account of result of Article 21.5 proceedings, Section 306 determinations have to be made “on the basis of the monitoring carried out” under Section 306(a). Such monitoring may include reference to Article 21.5 proceedings.

714 We note that at least one other WTO Member recently acted in a similar way. In Australia Salmon, Canada as well requested DSB authorization to suspend concessions within the 30 days framework even though there was disagreement as to whether Australia had implemented DSB recommendations and a panel under Article 21.5 is now examining this disagreement. In Australia Salmon. Canada took an approach similar to that of the US in order to preserve its rights under Article 22. At the DSB meeting of 28 July 1999, Canada stated the following: “in the context of the DSU review, both Australia and Canada had taken the same position on the interpretation of Articles 21.5 and 22: i.e. where there was a disagreement about implementation, a multilateral determination of inconsistency should precede the authorization to suspend concessions. Canada had tabled a detailed proposal to amend the DSU provisions with a view to ensuring such sequence. Since no agreement had yet been reached on this issue, Canada had to pursue its rights in accordance with the existing provisions of the DSU. At this stage, it was not possible for Canada to proceed with the Article 21.5 panel proceedings only, because such proceedings would be concluded after the expiry of the 30-day period provided for in Article 22, within which Canada had the right to request suspension of concessions by negative consensus” (WT/DSB/M/66, pp. 4-5). On the other hand, see the sequence and procedures agreed upon in Australia Leather, set out in footnote 709.

715 We realize that as a result it is still unclear whether the USTR is now (1) as the US argues, required to make determinations of inconsistency under Section 306 even pending Article 21.5 procedures in order to preserve US rights under Article 22 or (2) as the EC argues, prohibited under Article 23.2(a) to make such determinations until the completion of Article 21.5 procedures. We stress, however, that our task was to examine the compatibility of US law as such and not its application in a specific dispute, i.e. nol whether in a given dispute the USTR is allowed to make this or that determination. Under either hypothesis the US or the EC approach we found that Section 306 is not inconsistent with Article 23.2(a). This is now clearly established. Only the way Section 306 should be applied in a specific dispute an issue not falling within our mandate is left open.

716 See paras. 7.131-7.136 above.

717 See paras. 7.142-7.143 above.

718 We note that in addition to the discretion granted to the USTR under the first phase of Section 306 allowing it to delay a determination of non-implementation the USTR has also been granted a certain discretion under the second phase of Section 306, as well as under Section 301, allowing it not to determine what action to take until the completion of Article 21.5 procedures. The determination mandated in Section 306 on what action to take refers to “mandatory action” under Section 301(a). Section 301(a) itself provides for several exceptions where the USTR is not required to take action. Under this provision, action is not required, inter alia, if the DSB has adopted a report or ruling finding that US rights have not been denied; if the Member concerned is taking satisfactory measures to grant the US rights at issue under the WTO Agreement, including an expression of intention to comply with DSB recommendations; or if, in extraordinary cases, action would have a disproportionate adverse impact on the US economy or cause serious harm to the national security of the US. An additional discretionary element allowing the USTR to determine that no action is to be taken is that action under Section 301(a) is subject to “the specific direction, if any, of the President regarding any such action”. Even if the existence of the discretion under both phases of Section 306 and under Section 301 were to constitute a prima facie violation, the undertakings given by the US would remove these.

719 See paras. 7.131-7.136 above.

720 In respect of Article 21.5 procedures, see para. 7.145 above. Since Article 21.5 procedures may seemingly start on or about the date of expiry of the reasonable period of time and, as a general rule, take 90 days, it is likely that such procedures would not be completed within the 60 day deadline of Section 305. In respect of Article 22.6 arbitration procedures, we note that Article 22.6 provides that the arbitration has to be completed within 60 days after the expiry of the reasonable period of time, i.e. the time-limit in Section 305. However, even if the arbitration is completed by then, it may take some more time for the DSB to actually authorize the suspension of concessions consistent with the arbitration report. Considering footnote 7 in the Bananas III arbitration report (WT/DS27/ARB), even the completion of arbitration procedures within 60 days is not a certainty: “On the face of it, the 60-day period specified in Article 22.6 does not limit or define the jurisdiction of the Arbitrators ratione temporis. It imposes a procedural obligation on the Arbitrators in respect of the conduct of their work, not a substantive obligation in respect of the validity thereof. In our view, if the time-periods of Article 17.5 and Article 22.6 of the DSU were to cause the lapse of the authority of the Appellate Body or the Arbitrators, the DSU would have explicitly provided so. Such lapse of jurisdiction is explicitly foreseen, e.g. in Article 12.12 of the DSU which provides that ‘if the work of the panel has been suspended for more than 12 months, the authority for establishment of the panel shall lapse'”.

721 Thus, even if the US view on the relationship between Articles 21.5 and 22 were correct, the USTR could after having made determinations on WTO consistency and Section 301 action before the completion of Article 21.5 procedures as required, or at least authorized, under its reading of Article 22 still delay the implementation of any such action it may have determined to take until it has obtained DSB authorization to implement such action consistently with Article 23.2(c).

722 We note also that activation of Section 305 is dependent on a determination of action under Section 306 (second phase) and that the determination of action under Section 306 (second phase) is dependent on a “consideration” that implementation has not taken place under Section 306 (first phase). Since the initial trigger of determining that implementation has not taken place would following the EC view on the relationship between Articles 21.5 and 22 be removed the consequent implementation of action would also be delayed at least until completion of Article 21.5 procedures.

723 SAA, p. 366, fourth bullet point.

724 We agree with the US that if the maximum delay were imposed, the total of 240 days subsequent to the lapse of the reasonable period of time the original 60 day time-frame combined with the 180 days delay should be sufficient for the USTR to await in all cases the completion of both Article 21.5 and Article 22.6 procedures as well as DSB authorization to suspend concessions.

725 By so finding, we explicitly leave open the question of how DSB authorization to suspend concessions is to be applied ratione temporis, a question that is subject to another panel proceeding.

726 See paras. 7.131-7.136 above.

727 The EC seems to agree with this when it states, in para. 11 of its rebuttal submission, that “Section 301-310, on their face, mandate unilateral action by the US authorities in breach of Article 23 of the DSU ﹛and consequently of Articles I, II, III, VIII and XI of the GATT 1994)” (emphasised added).

728 In this respect we note, in addition, that action under Section 301 can also be consistent with GATT provisions even when it is not explicitly allowed under the DSU. This could be the case, for example, when the action consists of a rise in applied tariffs to a level within the bound rate, implemented on an MFN basis.

729 In its rebuttal submission, at p. 22, the EC only stated the following on this claim: “Given that Sections 304(a)(2)(A) and 306(b), as amended, require the United States to resort to retaliatory trade action within certain time limits irrespective of the result of WTO dispute settlement procedures, the actions taken in the area of trade in goods and not authorised pursuant to Article 3.7 and 22 of the DSU will necessarily be in violation of US obligations under one or more of the following GATT obligations: the Most-Favoured Nation clause (Article I GATT 1994), the tariff bindings undertaken by the United States (Article II GATT 1994), the National Treatment clause (Article III GATT 1994), the obligation not to collect excessive charges (Article VIII GATT 1994) and the prohibition of quantitative restrictions (Article XI GATT 1994)”. See para. 4.1013 of this Report.