No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

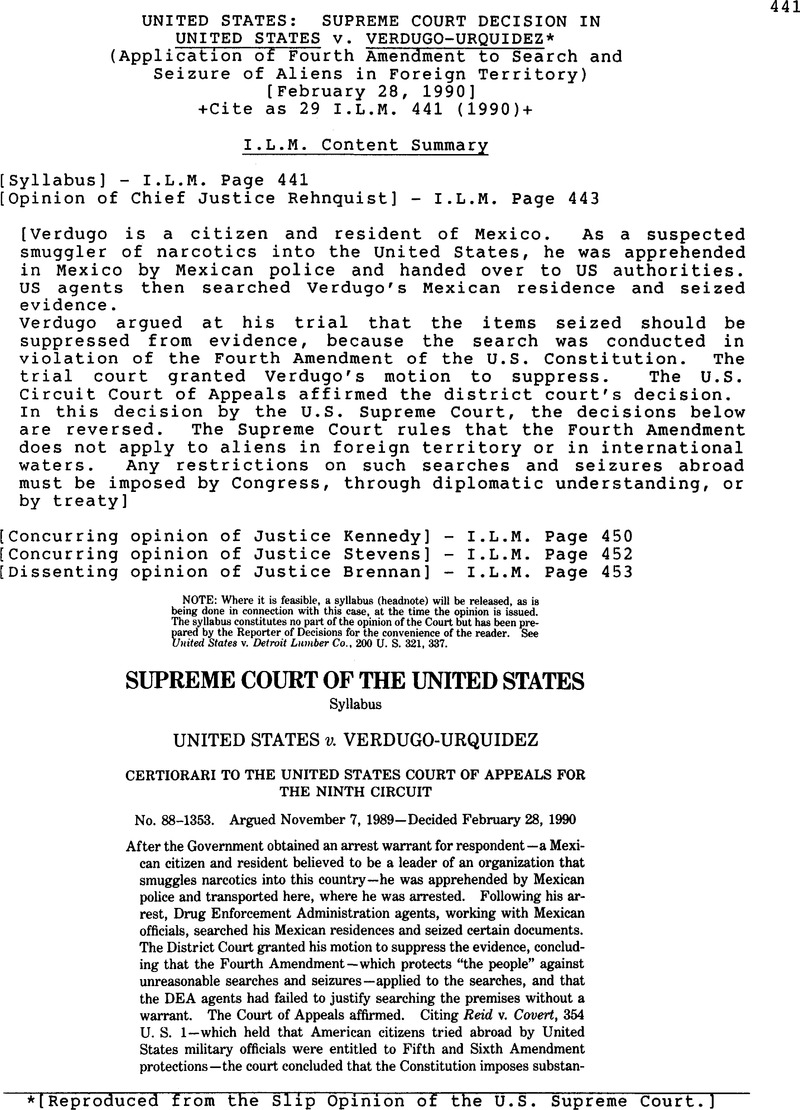

* Reproduced from the Slip Opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court.

* The Court's interesting historical discussion is simply irrelevant to the question whether an alien lawfully within the sovereign territory of the United States is entitled to the protection of our laws. Nor is comment on illegal aliens’ entitlement to the protections of the Fourth Amendment nec¬essary to resolve this case.

1 Federal drug enforcement statutes written broadly enough to permit extraterritorial application include laws proscribing the manufacture, dis¬tribution, or possession with intent to manufacture or distribute controlled substances on board vessels, see 46 U. S. C. App. §1903(h) (1982 ed.,Supp. V) (“This section is intended to reach acts … committed outside the territorial jurisdiction of the United States“), the possession, manufacture, or distribution of a controlled substance for purposes of unlawful importation, see 21 U. S. C. § 959(c) (same), and conspiracy to violate federal narcotics laws,see Chua Han Mow, v.United States, ,730 F. 2d 1308,1311-1312 (CA9 1984) (applying 21 U. S. C. §§ 846 and 963 to conduct by a Malaysian citizen in Malaysia), cert, denied, 470 U. S. 1031 (1985).

2 The Sherman Act defines “person” to include foreign corporations, 15 U. S. C. § 7, and has been applied to certain conduct beyond the territorial limits of the United States by foreign corporations and nationals for at least 45 years. See United States,v. Aluminum Co. of America, ,148 F. 2d 416, 443-444 (CA2 1945).

3 Foreign corporations may be liable under section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934,15 U. S. C. § 78j(b), for transactions that occur outside the United States if the transactions involve stock registered and listed on a national securities exchange and the alleged conduct is “detri¬mental to the interests of American investors.” Schoenbaum,v. First-brook, ,405 F. 2d 200,208 (CA2 1968), rev'd on rehearing on other grounds, 405 F. 2d 215 (CA2 1968) (en bane), cert, denied sub nom. Manley,v. Schoenbaum, ,395 U. S. 906 (1969).

4 See,e. g., , 18 U. S. C. §32(b) (violence against an individual aboard or destruction of any “civil aircraft registered in a country other than the United States while such aircraft is in flight“); § 111 (assaulting, resisting, or impeding certain officers or employees); § 115 (influencing, impeding, or retaliating against a federal official by threatening or injuring a family member); §§ 1114, 1117 (murder, attempted murder, and conspiracy to murder certain federal officers and employees); § 1201(a)(5) (kidnaping of federal officers and employees listed in § 1114); § 1201(e) (kidnaping of “an internationally protected person,” if the alleged offender is found in the United States, “irrespective of the place where the offense was committed or the nationality of the victim or the alleged offender“); § 1203 (hostage taking outside the United States, if the offender or the person seized is a United States national, if the offender is found in the United States, or if “the governmental organization sought to be compelled is the Government of the United States“); § 1546 (fraud and misuse of visas, permits, and other immigration documents); § 2331 (terrorist acts abroad against United States nationals); 49 U. S. C. App. § 1472(n) (1982 ed. and Supp. V) (aircraft piracy outside the special aircraft jurisdiction of the United States, if the offender is found in the United States). Foreign nationals may also be criminally liable for numerous federal crimes falling within the “special maritime and territorial jurisdiction of the United States,” which includes “[a]ny place outside the jurisdiction of any nation with respect to an offense by or against a national of the United States.” 18 U. S. C. §7(7). Fi¬nally, broad construction of federal conspiracy statutes may permit prosecution of foreign nationals who have had no direct contact with anyone or anything in the United States.See Ford,v. United States, ,273 U. S. 593, 619-620 (1927).

5 None of the cases cited by the majority, ante, ,at 10, require an alien's connections to the United States to be “voluntary” before the alien can claim the benefits of the Constitution. Indeed, Mathews, v. Diaz, 426 U. S. 67, 77 (1976), explicitly rejects the notion that an individual's connections to the United States must be voluntary or sustained to qualify for constitutional protection. Furthermore, even if a voluntariness require¬ment were sensible in cases guaranteeing certain governmental benefits to illegal aliens, e. g., Plyler, v. Doe, 457 U. S. 202 (1982) (holding that States cannot deny to illegal aliens the free public education they provide to citizens and legally documented aliens), it is not a sensible requirement when bur Government chooses to impose our criminal laws on others.

6 In this discussion, the Court implicitly suggests that the Fourth Amendment may not protect illegal aliens in the United States. Ante, ,at 11-12. Numerous lower courts, however, have held that illegal aliens in the United States are protected by the Fourth Amendment, and not a sin¬gle lower court has held to the contrary. See, e. g., Benitez-Mendez,v. INS, ,760 F. 2d 907 (CA9 1985); United States,v. Rodriguez, ,532 F. 2d 834, 838 (CA2 1976); Au Yi Lau v. INS, 144 U. S. App. D. C. 147, 156, 445 F. 2d 217,225, cert, denied, 404 U. S. 864 (1971); Yam Sang Kwai, v. INS, 133 U. S. App. D. C. 369, 372, 411 F. 2d 683, 686, cert, denied, 396 U. S. 877 (1969).

7 The Fourth Amendment contains no express or implied territorial limi¬tations, and the majority does not hold that the Fourth Amendment is in¬applicable to searches outside the United States and its territories. It holds that respondent is not protected by the Fourth Amendment because he is not one of “the people.” Indeed, the majority's analysis implies that a foreign national who had “developed sufficient connection with this country to be considered part of [our] community” would be protected by the Fourth Amendment regardless of the location of the search. Certainly nothing in the Court's opinion questions the validity of the rule, accepted by every Court of Appeals to have considered the question, that the Fourth Amendment applies to searches conducted by the United States Government against United States citizens abroad. See, e. g., United States,v. Conroy, ,589 F. 2d 1258, 1264 (CA5), cert, denied, 444 U. S. 831 (1979); United States,v. Rose, ,570 F. 2d 1358, 1362 (CA9 1978). A war¬rantless, unreasonable search and seizure is no less a violation of the Fourth Amendment because it occurs in Mexicali, Mexico, rather than Calexico, California.

8 President John Adams traced the origins of our independence from England to James Otis’ impassioned argument in 1761 against the British writs of assistance, which allowed revenue officers to search American homes wherever and whenever they wanted. Otis argued that “[a] man's house is his castle,” 2 Works of John Adams 524 (C. Adams ed. 1850), and Adams declared that “[t]hen and there the child Independence was born.” 10 Works of John Adams 248 (C. Adams ed. 1856).

9 The majority places an unsupportable reliance on the fact that the drafters used “the people” in the Fourth Amendment while using “person” and “accused” in the Fifth and Sixth Amendments respectively, see ante, at 5. The drafters purposely did not use the term “accused.” As the majority recognizes, ante, ,at 4, the Fourth Amendment is violated at the time of an unreasonable governmental intrusion, even if the victim of unreasonable governmental action is never formally “accused” of any wrongdoing. The majority's suggestion that the drafters could have used “person” ignores the fact that the Fourth Amendment then would have begun quite awkwardly: “The right of persons to be secure in their persons ….“

10 The only historical evidence the majority sets forth in support of its restrictive interpretation of the Fourth Amendment involves the seizure of French vessels during an “undeclared war” with France in 1798 and 1799. Because opinions in two Supreme Court cases, Little, v. Barreme, 2 Cranch 170 (1804), and Talbot,v. Seeman, ,1 Cranch 1 (1801), “never suggested that the Fourth Amendment restrained the authority of Congress or of United States agents to conduct operations such as this,” ante, ,at 7, the majority deduces that those alive when the Fourth Amendment was adopted did not believe it protected foreign nationals. Relying on the absence,of any discussion of the Fourth Amendment in these decisions, however, runs directly contrary to the majority's admonition that the Court only truly de¬cides that which it “expressly addresstes].” Ante, ,at 11 (discussing INS,v. Lopez-Mendoza, ,468 U. S. 1032 (1984)). Moreover, the Court in Little,found that the American commander had violated the statute authorizing seizures, thus rendering any discussion of the constitutional question su¬perfluous. See, e. g., Ashivander,v. TV A, ,297 U. S. 288, 347 (1936) (Brandeis, J., concurring). And in Talbot, ,the vessel's owners opposed the seizure on purely factual grounds, claiming the vessel was not French. Furthermore, although neither Little,nor Talbot,expressly mentions the Fourth Amendment, both opinions adopt a “probable cause” standard, sug¬gesting that the Court may have either applied or been informed by the Fourth Amendment's standards of conduct. Little, supra, ,at 179; Talbot, supra, ,at 31-32 (declaring that “where there is probable cause to believe the vessel met with at sea is in the condition of one liable to capture, it is lawful to take her, and subject her to the examination and adjudication of the courts“).

11 The last of the Insular Cases cited by the majority, Dowries,v. Bid/well, ,182 U. S 244 (1901), is equally irrelevant. In Daumes, ,the Court held that Puerto Rico was not part of “the United States” with respect to the constitutional provision that “all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States,” U. S. Const., Art. I, § 8, cl. 1. 182 U. S., at 249. Unlike the uniform duties clause, the Fourth Amendment contains no express territorial limitations.See n. 7, supra.

12 The District Court found no exigent circumstances that would justify a warrantless search. After respondent's arrest in Mexico, he was trans¬ported to the United States and held in custody in southern California. Only after respondent was in custody in the United States did the Drug Enforcement Administration (DE A) begin preparations for a search of his Mexican residences. On the night respondent was arrested, DEA Agent Terry Bowen contacted DEA Special Agent Walter White in Mexico to seek his assistance in conducting the search. Special Agent White con¬tacted Mexican officials the next morning and at 1 p.m. authorized Agent Bowen to conduct the search. A team of DEA agents then drove to Mex¬ico, met with Mexican officials, and arrived at the first of respondent's two residences after dark. 856 P. 2d 1214, 1226 (CA9 1988). The search did not begin until approximately 10 p.m. the day after respondent was taken into custody. App. to Pet. for Cert. 101a. In all that time, particularly when respondent and Agent Bowen were both in the United States and Agent Bowen was awaiting further communications from Special Agent White, DEA agents could easily have sought a warrant from a United States Magistrate.

13 Justice Stevens concurs in the judgment because he believes that the search in this case “was not ‘unreasonable’ as that term is used in the first clause of the Amendment.” Ante, at. I do not understand why Justice Stevens reaches the reasonableness question in the first instance rather than remanding that issue to the Court of Appeals. The Dis¬trict Court found that, even if a warrant were not required for this search,the search was nevertheless unreasonable. The court found that the search was unconstitutionally general in its scope, as the agents were not limited by any precise written or oral descriptions of the type of documentary evidence sought. App. to Pet. for Cert. 102a. Furthermore, the Government demonstrated no specific exigent circumstances that would justify the increased intrusiveness of searching respondent's residences between 10p.m. and 4 a.m., rather than during the day. Id., at 101a. Finally, the DEA agents who conducted the search did not prepare contemporaneous inventories of the items seized or leave receipts to inform the residents of the search and the items seized. Id., at 102a. Because the Court of Appeals found that the search violated the Warrant Clause, it never reviewed the District Court's alternative holding that the search was unreasonable even if no warrant were required. Thus, even if I agreed with Justice Stevens that the Warrant Clause did not apply in this case, I would remand to the Court of Appeals for consideration of whether the search was unreasonable. Barring a detailed review of the record, I think it is inappropriate to draw any conclusion about the reasonableness of the Government's conduct, particularly when the conclusion reached contra¬dicts the specific findings of the District Court. Justice Kennedy rejects application of the Warrant Clause not be¬cause of the identity of the individual seeking protection, but because of the location of the search. See ante, at 4 (Kennedy, J., concurring) (“[T]he Fourth Amendment's warrant requirement should not apply in Mexico as it does in this country“). Justice Kennedy,however, never explains why the reasonableness clause, as opposed to the Warrant Clause, would not apply to searches abroad.

14 The United States Government has already recognized the importance of these constitutional requirements by adopting a warrant requirement for certain foreign searches. Department of the Army regulations state that the Army must seek a “judicial warrant” from a United States court whenever the Army seeks to intercept the wire or oral communications of a person not subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice outside of the United States and its territories. Army Regulation 190-53 12-2(b) (1986). Any request for a judicial warrant must be supported by sufficient facts to meet the probable cause standard applied to interceptions of wire or oral communications in the United States, 18 U. S. C. § 2518(3). Army Regulation 190-53 1 2-2(b). If the foreign country in which the interception will occur has certain requirements that must be met before other nations can intercept wire or oral communications, an American judicial warrant will not alone authorize the interception under international law. Nevertheless, the Army has recognized that an order from a United States court is necessary under domestic law. By its own regulations, the United States Government has conceded that although an American warrant might be a “dead letter” in a foreign country, a warrant procedure in an American court plays a vital and indispensable role in circumscribing the discretion of agents of the Federal Government.