Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

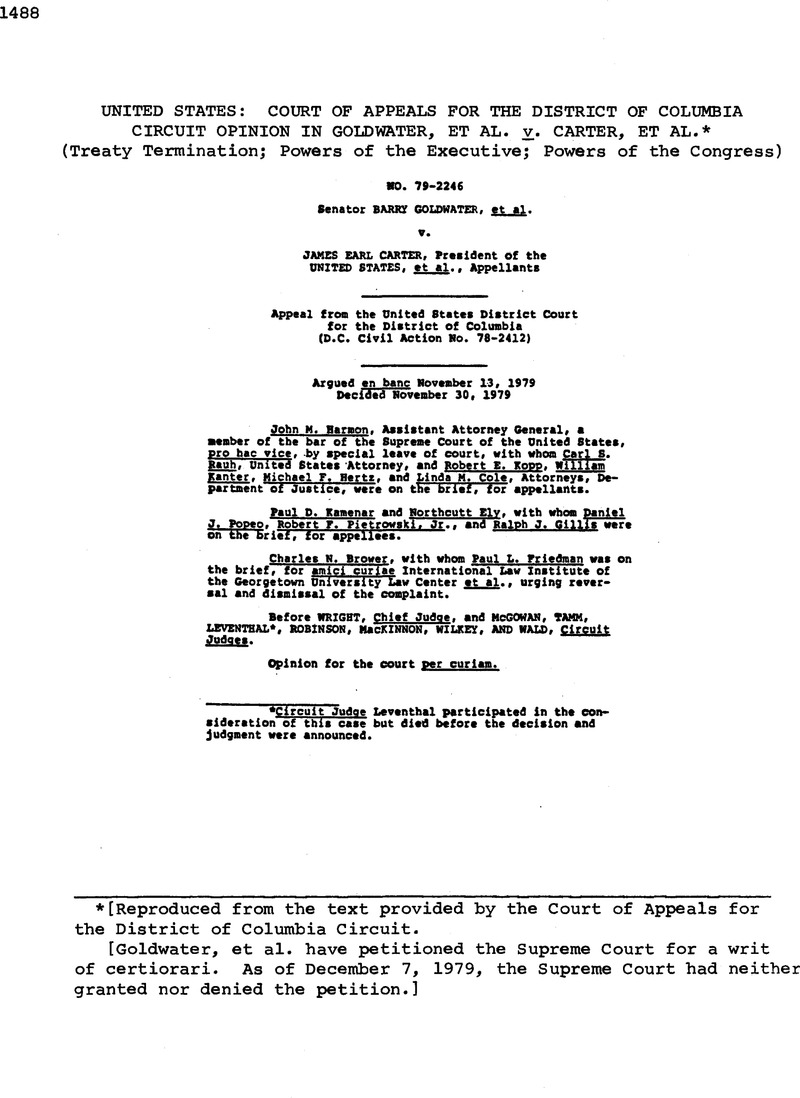

[Reproduced from the text provided by the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

[Goldwater, et al. have petitioned the Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari. As of December 7, 1979, the Supreme Court had neither granted nor denied the petition.]

page 1489 note 1/ In a separate concurring opinion. Judges Wright and Tamm have limited their consideration to the question of standing; and, finding that none exists, vote to reverse the District Court. There are no votes to reverse founded upon the political question doctrine.

page 1489 note 2/ Amici in this court cast their argument in terms of a mootness disposition which assertedly would make it unnecessary to decide whether the President could, without congressional participation, terminate the Treaty by giving notice in accordance with its terms. They Submit that the President's action in. recognizing the People's Republic of China and in withdrawing recognition of the Republic of China, arising out of changed circumstances, of its own force under international law brought an end to the MutualDefense Treaty between the latter and the United States. This end, so it is said, occurred automatically, and thus there is no necessity for the court to rule upon the validity of the notice of termination which in substance had no meaning or effect.

Without intimating any view on the accuracy of the amici's premises, we do not pursue the mootness claim for the reason that the President did not purport to rely on international law as a possible defense against any future claim that the Treaty was a continuing obligation of the United States despite the events enumerated by the amici. Instead, the President elected to assert, on behalf of the United States, the privilege of terminating the Treaty by appropriate notice as provided by its own terms. A proper functioning of such a mutual termination clause is to permit a party to a treaty to respond to a change in circumstanceswithout becoming embroiled in disputes as to the reach of international law doctrines. As we bold hereinafter, this course of action was, on the facts in this record, within the constitutional authority of the President.

page 1491 note 3/ Taiwan Relations Act, Pub. L. No. 96-8, 93 Stat. 14, S 2(b)(1) (April 10, 1979). Relations between the United States Government and the authorities .on Taiwan are conducted through a nonprofit corporation, the American Institute in Taiwan. Id. $ 6.

page 1491 note 4/ Section 3 of the Act authorises the United States to provide defense material to Taiwan, and says that “[t]he President and the Congress shall determine the nature and quantity of such defense articles and services based solely upon their judgment of the needs of Taiwan.” It further directs the President to report to the Congress on “any threat to the security or the social or economic system of the people on Taiwan and any danger to the interests of the United States arising therefrom.” The President and theCongress then “shall determine *** appropriate action by the United States in response to any such danger.” Id. $ 3.

page 1492 note 5/ Only one of the resolutions, Senate Resolution 15, Introduced by Senator Barry Byrd, Jr., reached the floor of the Senate. See also 6. Res. 10, 125 Cong. Rec. 8209 (daily ed. Jan. 15, 1979) (introduced by Senator Dole) L.S. Con. Res. 22, id at 8219 (daily ed. Jan. 18, 1979) (introduced by Senator Goldwater).

page 1492 note 6/ Among other grounds, the Committee version would have recognised the right of the President to terminate treaties containing termination clauses like Article X of the 1954 Treaty.

page 1492 note 7/ After oral argument was beard in this court, the Senate debated the resolution, but again took no action. 125 Cong. Rec. S16683-S16692 (daily ed. Hov. 15, 1979)y As explained by Senate Parliamentarian Murray Sweben, no final action has been taken on Senate Resolution 15, and the Senate “may or may not return to its consideration in the future.” JA 659.

page 1493 note 8/ See Warth v. Seldin, 422 0.6. 490, 501 (1975).

page 1493 note 9/ fee Barrington v. Bush, 5S3.F..2d 190, 211-12 D.C. Cir. 1977); Kennedy v. Sampson,VS11 F.2d 430, 435-36 (D.C. Cir. 1974).

page 1493 note 10/ See Beuss v. Bailee, 584 F.2d 461, 467-68 & n.20 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied. 439 U.S. 997 (1978)j Metcalf v. Rational Petroleum Council, 553 P.2d 176, 1BB-B9 (D.C. Cir. 1977)| Harrington v. Bush, 553 P.2d 190, 199 n.41, 211-14 (D.C. Cir. 1977).

page 1494 note 11/ gee Harrington v. Bush, 553 P.2d 190, 212 (D.C. Cir. 1977).

page 1494 note 12/ In his concurrence, (pp. 4-5),Chief Judge Wright also attempts to limit congressional standing to nullification of past votes, citing Kennedy v. Sampson. 511 P.2d 430 (D.C. Cir. 1974). Nothing in Kennedy v. Sampson, nor in the logic of what constitutes injury in fact, justifies such a limitation. On the contrary, a claim of nullification of past vote alone— based, for instance, on the Executive's failure to obey a validly enacted statute—gives a legislator no better grounds for standing than any other citisen. Courts nave properly denied standing to legislators in such situations. “Once a bill has become law, however, their Interest -is indistinguishable from that of any other citisen.” Harrington v. Schlesinger, 528 P.2d 455, 459 (4th Cir. 1975). See Harrington v. Bush, 553 P.2d 190, 213-14 (D.C. Cir. 197777

page 1494 note 13/ At oral argument counsel for the appellants admitted this second point. He stated, in the words that follow that even if the Taiwan Relations Act applied to the Taiwan treaty, that would not override the President's constitutional power to break the Treatyi “Congress could not end that power by passing a law, and the President could not waive it by signing a law.”

page 1495 note 14/ The President's powers are there stated in site following terms:

Be shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concure and be shall nominate and by and with tbe Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls....

page 1496 note 15/ This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of tbe Land} and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in tbe Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

page 1497 note 16/ L. Benkln, Foreign Affairs and the Constitution 169 (1972).

page 1497 note 17/ Contrastingly, Article I, Section 1, provides: “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States....”(emphasis supplied).

page 1499 note 18/ Since the first treaty to which the United States was a party was terminated in 1798 by an act of Congress, a variety of means have been used to terminate treaties: by statute directing the President to deliver notice of termination; by the President acting pursuant to a joint resolution of Congress or otherwise acting with the concurrence of both houses of Congress; by the President acting with senatorial consent} and by the President acting alone.

Goldwater v. Carter, So. 78-2412, slip op. at 18-19 (D.D.C. Oct. 17, 1979) (footnotes omitted).

page 1499 note 19/ The Senate Committee on Foreign Relations after careful consideration of the matter came to the conclusion that there were 14 different bases on which the President could terminate a treaty in the course of his executive function. The grounds identified are the following:

(1) in conformity with the provisions of the treaty;

(2) by consent of all the parties after consultation with the other contracting states;

(3) where it is established that the parties intended to admit the possibility of denunciation or withdrawal;

(4) where a right of denunciation or withdrawal may be implied by the nature of the treaty;

(5) where it appears from a later treaty concluded with the same party and relating to the same subject matter that the matter.should be governed by that treaty; —

(6) where the provisions of the later treaty are so far incompatible with those of the earlier one that the two treaties are not capable of being applied at the same time;

(7) where there has been a material breach by another party;

(8) where the treaty has become impossible to perform;

(9) where there has been a fundamental change of circumstances;

(10) where there has been a severance of diplomatic or consular relations and such relations are indispensable for the application of the treaty;

(11) where a new peremptory norm of international law emerges which is In conflict with the treaty;

(12) where an error was made regarding a fact or situation which was assumed by .that state to exist at the time when the treaty was concludedand formed an essential basis -of its consent to-be bound;

(13) where a state has been Induced to conclude a treaty by the fraudulent conduct of another state; and

(14) where a state's consent to be bound has been procured by the corruption or coercion of its representatives or by the threat or use of force.

S. Rep. No. 119, 96th Cong., 1st Bess. 10 (1979).

page 1500 note 20/ United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., 299 U.S. 304, 320 (1936) (Sutherland, J.).

page 1501 note 21/ The United States declared: “The United States acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that-Taiwan- is a part of China. The United States Government does not challenge that position.” 66 Dep't State-Bull. 435 (1972).

page 1501 note 22/ “The United States of America recognises the Government of the People's Republic of China as the sole legal Government of China. Within this context, the people of the United States will maintain cultural, commercial, and other unofficial relations with the people of Taiwan.” 14 Weekly Comp. of Pres. Doc. 2264 (Dec. 18, 1978).

page 1501 note 23/ Taiwan Relations Act, Pub. L. 96-8, 93 Stat. 14 (April 10, 1979).

page 1502 note 24/ fee United States v. Pink, 315 U.S. 203, 229-230 (1942); United States v. Belmont, 301 U.S. 324, 330 (1937); U.S. Const, art. XI, S 3 (the President “shall receive ambassadors and other public Ministers”).

page 1502 note 25/ Appellees urge that the Treaty had continuing validity because of the de facto existence of Taiwan. What government—de facto or de jure—is representative of a foreign state is a question to be determined by the political department, and thus is beyond the ambit of judicial review. United States v. Pink, 315 U.S. 203, 229 (1942)} Jones v. United States, 137 U.S. 202, 212-14 (1890).

page 1503 note 26/ We note that Judge MacKinnon's position also requires a reversal of the District Court. Judge Gascb's judgment forbids further action to terminate the treaty without either consent of the Senate by a two-thirds vote or. a vote by a majority of both Bouses of Congress. Judge MacKinnon clearly would require action by both Bouses; henceJudge Casch's approval of Senate advice and consent as sufficient is reversed without dissent.