Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

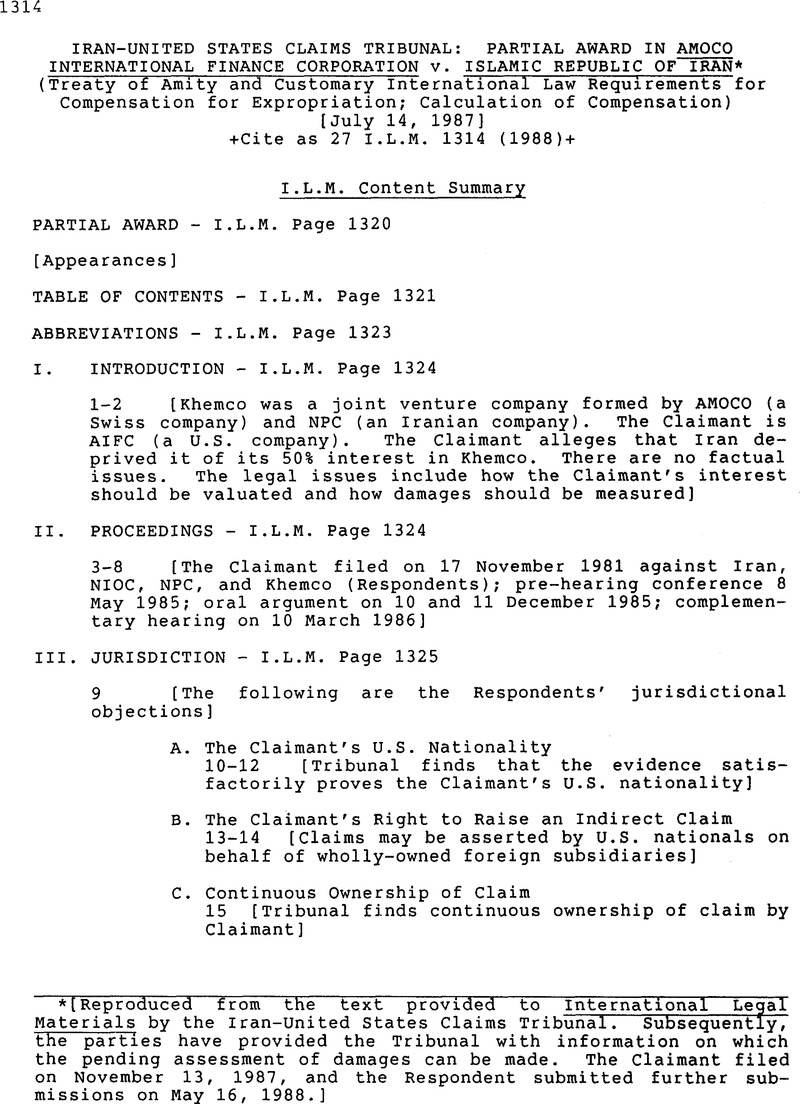

* [Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by the Iran–United States Claims Tribunal. Subsequently, the parties have provided the Tribunal with information on which the pending assessment of damages can be made. The Claimant filed on November 13, 1987, and the Respondent submitted further submissions on May 16, 1988.]

1 According to the Respondents, the phrase “shall be annulled” in the Single Article Act must be read to mean “are null and void ab initio.”

2 Reparation, as the Court sees it, would cover restitutio, or its monetary equivalent, plus any potential consequential damages, in order to “wipe out all the consequences of the illegal act.”

3 Note the use of the term of lucrum cessans by the Court in the part of the judgment” which confirms the interpretation of Question I.

4 This does not seem to have been questioned by any of the judges, although Judge Rabel, in “observations” appended to the judgment, expressed his regrets that this was not expressly said by the Court. The other judges dissenting on this point considered that the compensation should be limited to the value of the undertaking at the date of the taking without any right to an enhanced value.

5 see, e.g., Republic of Egypt, S.P.P.(Middle East)Limited, v. Arab (Bernini, Elghatit, Littman arbs., Award of 11 March 1983), reprinted in 22 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 752, 782-783 (1983); for a description of the practice of the U.S. Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, see R. B. Lillich, “The Valuation of Nationalized Property by the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission” in 1 The Valuation of Nationalized Property in InternationaI∼∼Law∼ 95-116 (W. ST Lillich ed. 1972).

6 See, e.g., U.S.R. Int T (Middle East) Arb\Awards307, Limited, v. Arab Republic of Egypt, Lillich. supra, at 95-116. Norwegian Shipowners Claims (Norway v. 33 T922) ;S.P.P.

1 The Tribunal found no stabilization clause present and saw no other basis for invalidating the takin per see.

2 In Sedco the Tribunal found there had been an expropriation commencing with the appointment of “temporary” managers. The Tribunal noted: When … the seizure of control by appointment of “temporary” managers clearly ripens into an outright taking of title, the date of appointment presumptively should be regarded as the date of taking …. When, as in the instant case, it also is found that on the date of the government appointment of “temporary” managers there is no reasonable prospect of return of control, a taking should conclusively be found to have occurred as of that date. Sedco, Inc. and National Iranian Oil Company, Award No.ITL 55-129-3 at 41-42 (28 Oct. 1985).

3 “For every force there is an equal and opposite force or reaction.” Webster's Third New International Dictionary 280 (1976).

4 The fact, if true, that the parties continued after that date to discuss the possibility of an agreed transfer, which would have settled their differences, does not affect the character of Respondents’ acts as of that date.

5 As will be seen in Sections III and IV, infra, especially n. 30, the monetary award in the instant case most likely should be the same whether the taking of Claimant's property be regarded as lawful or unlawful, i.e., the full value of Claimants’ interest in the Khemco Agreement. To the extent the Award suggests a greater amount should be due in the latter event, however, it would be my view that it should be granted.

6 See Separate Opinion of Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice in Kuwait and American Independent Oil Company (AMINOIL), para. 23(4) (Award of 24 March 1982), reprinted in 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 1043, 1050 (1982).Of (Mahmassani Libyan Arab Republic, arb., Award of 12 April 1977, reprinted in 62 I.L.R. 139, 163-64 (1982).

7 The Libyan decrees in Topco and LIAMCO also provided specifically for “compensation” to ∼Ee assessed by a committee (although this never was implemented). Texaco Overseas Petroleum Company v. Libyan Arab Republic (“TOPCO“), para. 6 (Dupuy arb.. Award of 19 January 1979) , reprinted in 53 I.L.R. 389, 425-26 (1979); Libyan American Company (LIAMCO).

8 Experience subsequent to this date would be of evidentiary value to the extent consistent with earlier experience. In the absence of any indication in the record, however, that any experience under the Act was gained in the nearly full year intervening between promulgation of the Act on 8 January 1980 and 24 December 1980, the interpretive value of the experience cited is slight at best.

9 The same principle has repeatedly led international tribunals, including this one, to reject claims settlements as delineating in any degree the international law standard of compensation for expropriation. See Sedco, Inc. and Rational Iranian Oil Company, Award No. ITL 59-129-3 at 13 (27 March 1986) (collecting cases), reprinted in 25 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 629, 635 (1986); id., Separate Opinion o? Judge Brower at 10-11, reprinted “In 25 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 636, 641.

10 I agree that this taking appears to have been for a public purpose, and am also inclined to give Respondents the benefit of such doubt as may exist regarding whether or not it was discriminatory. that the international is limited to treaty that, however, there is a.

11 1 read the Award to say (1) law rule of pacta sunt servanda relations between States;(2) general principle of law, which itself has become a rule of international law, particularly as enshrined in the United Nations Resolution of 1962 on Permanent Sovereignty Over Natural Resources, G.A. Res. 1803 (XVII) (1962), reprinted in Basic Documents in International Law 141-43 (I. Brownlie 2“d” ed. 1972) , and consolidated by Article V of the Claims Settlement Declaration, “that a State has the duty to respect contracts freely entered into with a foreign party” (para. 177), subject always to the State's lawful (e.g., non-discriminatory) exercise of its sovereign power for a public purpose (e.g., nationalization); (3) that a State may make a binding legal commitment not to exercise such power; but (4) that such a commitment is not easily established, and certainly is not so where the sovereign is not itself a party to the overall contract with the foreign national and the period of asserted commitment is rather long. I comment only on the last of these propositions.

12 The accompanying “grant” of “facilities and privileges” by contrast refers inclusively to those accorded under specified enactments, including “any future amendments to such acts.” The latter phrase clearly is intended to extend to the enterprise any additional facilities and privileges created in the future, and not to permit any reduction in those initially granted. It thus i” consistent with the view that the Agreement does contain a stabilization clause and does not contradict it as the Award supposes.(Para. 167.)

13 The fact that Khemco is not mentioned in this provision either, from which the Award draws comfort on this point (para. 172), is likewise of no significance. It is true that Khemco is not bound by certain articles of the Khemco Agreement notwithstanding its having become a party to it. There was no reason to refer to it in Article 21(2) along with NPC and Amoco because it had no interest in preservation of the contractual status quo independent of the interests of its two equal shareholders.

14 But see LIAMCO, supra, 62 I.L.R. at 217 (ruling on unelaborated grounds that the breach of clauses identical to those in TOPCO was “not unlawful as such, and constituted] not a tort but a source of liability to compensate“). I see no material distinction necessarily resulting from the fact that Libya itself was a party to the complete agreement containing these clauses, whereas Iran was not a party as •uch to the Khemco Agreement. In either case the adjudicative task is to determine on the basis of the entire record whether the sovereign undertook a binding legal obligation.

15 Similar provisions were considered by the tribunal in AMINOIL under the rubric of stabilization: Save as aforesaid this Agreement shall not be terminated before the expiration of the period specified in Article 1 thereof except by surrender as provided in Article 12 or if the Company shall be in default under the arbitration provisions of Article 18.The Shaikh shall not by general or special legis-lation or by administrative measures or by any other act whatever annul this Agreement except as provided in Article 11. No alteration shall be made in the terms of this Agreement by either the Shaikh or the Company except in the event of the Shaikh and the Company jointly agreeing that it is desirable in the interest of both parties to make certain alterations, deletions or additions to this Agreement.Kuwait and American Independent Oil Company (AMINOIL), paras, xxxill” 88 (Reuter, Sultan & Fitzmaurice arbs., Award Of 24 March 1982), reprinted in 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 976, 992, 1020 (1982). The tribunal in that case (with Judge Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice disagreeing) declined to give these articles effect as stabilization clauses because it felt a more explicit committment to self-restraint should be required where a 60-year concession was considered..Id., para. 95, 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 1023. (The instant case involves a contract for a minimum of 35 years.) In addition, the tribunal found these articles “no longer possessed of their former absolute character” due to “a metamorphosis in the whole character of the Concession” over a period of nearly thirty years since 1948. Id., paras. 97, 100, 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 1023-24.

16 The Company will pay N1oc and Paniktoil, and NIOC and Panintoil will each receive, two cents (US $0.02) per 1000 SCF (approximately equivalent to seventy and sixty two one hundredths cents - U.S. $0.7062 - per 1000 Standard Cubic Meters) for their respective separate one-half quantity of the gas sold to the Company, delivered at the appropriate location on Kharg Island. Such price will remain fixed for fifteen (15) years from the date of commencement of commercial production of the plants. After the expiration of this tif teen-year period, the price to be paid for the Natural Gas to be purchased during each subsequent five-year period may be adjusted by an amount agreed upon between the Company and NIOC and PANINTOILT provided that no such adjustment will reduce the ratio of the Company's average f.o.b. unit sales price of each of its products to its average unit cost for each such product (including selling cost) during the applicable subsequent five-year period below that which existed during the preceding five-year period, provided further, that such adjustment will never result in reducing the price of gas below two cents (US $0.02) per 1000 SCF, and also provided that the price for such gas will not exceed the price charged to other petrochemical and chemical consumers of such gases in Iran (companies wholly owned by NPC and NIOC, manufacturing products for internal consumption in Iran not included). Article23 readsas Article8.1.a(emphasisadded), follows: This Agreement shall remain in force for so long as the aforementioned Joint Structure Agreement between NIOC and Panintoil continues in effect or for a period of thirty-five (35) years from the Effective Date, whichever is the longer period, and may be extended at the request of NPC or AMOCO for additional periods each of fifteen (15) years on basis and terms to be agreed. For the implementation of this Article, both parties shall begin negotiations upon the matter not less than five(5)years before the expiration of the then (Footnote Continued)- 14 -The absence of such a provision suggests that a stabilization was intended in Articles 21(2) and 30(2).14. If, as I believe, the expropriation here was contrary to an undertaking by Iran to stabilize the Khemco Agreement, then it was for this reason as well an unlawful act. See AGIP v. Popular Republic of the Congo, paras. 86-88 (Trolle, Dupuy t Rouhani arbs., ICSID Award of 30 Nov. 1979), reprinted in 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 726, 735-36 (1982); TOPCO, supra, para. 71, 53 I.L.R. at 477; BP Exploration Company (Libya Ltd.) v. Government of the Libyan Arab Republic (Lagergren arb., Award of 1 Aug. 1974), reprinted in 53 I.L.R. 297, 329 (1979); Separate Opinion of Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice in AMINOIL, supra, 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 1043. (Footnote Continued)current period of the Agreement.Article 23 (emphasis added).

17 See, for examples of such a clause, Supplemental Agreement to the 1960 ‘LAMCO’ Agreement between the Republic of Liberia, the Liberian American-Swedish Minerals Co. and Liberia Bethlehem Iron Mines Co. of 1974, para. 24 (“In case of profound change in the circumstances existing at December 31, 1973, the parties, at the request of any one of them, will consult together for the purpose of considering such changes in or clarifications of this Mining Concession Agreement as the parties deem to be appropriate“) (quoted in W. Peter, Arbitration and Renegotiation of International Investment Agreements;FI4,S3.2.1,at ITS(1986)); xxxiv, 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 992 AMINOIL, supra, para. (“If, as a result of changes in the terms of concessions now in existence or as a result of the terms of concessions granted hereafter, an increase in benefits to Governments in the Middle East should come generally to be received by them, the Company shall consult with the Ruler whether in the light of all relevant circumstances, including the conditions in which operations are carried out, and taking into account all payments made, any alterations in the terms of the agreements between the Ruler and the Company would be equitable to the parties’).

18 The Award's statement (para. 189) that the issue of “lawfulness or unlawfulness” of the taking “must be decided by reference to customary international law” is correct as a fundamental proposition. As the Treaty of Amity establishes applicable law regarding the requisites for expropriation, however, breach of the Treaty rules constitutes an unlawful act. Furthermore, the Treaty requirement that an expropriated party be provided the “full equivalent of the property taken” must be respected when a taking violates the Treaty, i.e., no less could be granted regardless of what customary law might otherwise provide.

19 The Award does not explain why or how it comes to treat the expropriation (through repudiation or “nullification“) of the Khemco Agreement-as the expropriation of an enterprise (implicitly without a contractually fixed life span). One suspects that this unexplained and, in my view, unjustified transformation has influenced the Award to view the question of compensation somewhat differently than it should.

20 I of course agree that the Treaty of Amity covers Claimant's “interests in property” held through its wholly owned Swiss subsidiary. Sedco, Inc. and National Iranian Oil Company, Award No. 309-129-3 at 22-23 n∼. 5 (7 July 1987).

21 The Court itself nowhere uses the term damnum emergens. I therefore fail to see that its use of lucrum cessans necessarily confirms the Award's reading of Chorzów Factory.(Para. 204, n. 3.)

22 At various places the judgment in Chorzow Factory, if read literally, appears to require that an unlawfully expropriated party be awarded the value of the undertaking as it appears at the time of judgment, even if this be less than the value assessed as of the date of taking. See, e.g., references to “its value at the time of the indemnification,” 1928 P.C.I.J. Ser. A, No. 17 at 48; “the value which the undertaking … would have had at present,” id. at 50; and “the present value of the undertakingT“” id. at 59. Such a result would be in keeping with the principle of restitutio in integrum, the object of which is “to restore the undertaking,” id. at 48. It would have the anomolous result, however, of rewarding the expropriating State for its unlawful conduct: Absent any consequential damages, which the Court in Chorz6w Factory would award, or consideration of punitive damages, which the Award here flatly rejects (para. 197, but see Separate Opinion of Judge Brower in Sedco, Inc. and National Iranian Oil Company, supra, at 24-25, nn. T4-35, 25 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 648-49), the host State would pocket the difference between the lower value the undertaking was shown by post-taking experience to have had and the higher value it objectively enjoyed at the moment of taking. As no system of law sensibly can be understood as intended to reward unlawful conduct, Chorz6w Factory must be read as I have suggested, a reading supported by other portions of the judgment (see, e.g., the statement at page 50 that “the value of the undertaking at the moment of dispossesion does not necessarily indicate the criteria for the fixing of compensation“) and the Observations of Judge M. Rabel: … [T]he principles resulting from the unlawful nature of the expropriation … are applicable in practice whenever the damage caused appears greater than the compensation which would be due if expropriation had been lawful …. It is in fact obvious that the expropriator's responsibility must be increased by the fact that his action is unlawful …. [I]t is …

23 Although the Court's language here appears in the context of discussions as to whether separate damage awards are to be made as to each of two industrial plants or a single collective amount is to be given, I believe it is broadly reflective of the Court's views regarding the “value of the undertaking.”

24 It is noteworthy that the tribunal in AMINOIL referred to “the value … of the undertaking. ‘ * the exact phrase of Chorzόw Factory — “as a source of profit.” AMINOIL, supra, para. 164, 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 1038.

25 This passage as a whole confirms the suggestion above (para. 23(2)) that to read “the value of the undertaking” in Question I as including prospective profits should not necessitate their double counting.

26 The Award's stance in respect of lost profits is further contradicted by AMINOIL and LIAMCO; both awarded an amount representing lost profits. AMINOIL, supra, para. 176 (2), 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 1041; LIAMCO, supra, 62 I.L.R. at 217-T81 Indeed, the AMINOIL tribunaTTs refusal to enforce a stabilization clause was expressly conditioned: Kuwait's “take-over’ of Aminoil's enterprise was not … inconsistent with the contract of concession, provided always that the nationalisation did not possess any confiscatory character.” AMINOIL, supra, para. 102, 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 1024 (emphasis added). Thus while a finding that an expropriation was not unlawful by reason of inconsistency with a stabilization clause may lead some to award less by way of lost profits than would in fact have been projected for the full contract term, even in such cases an award of material profits has resulted.

27 Hence the Award's concerns that the Tribunal is asked to do an 18-year projection (as opposed to 39 in AMINOIL) (para. 236), that there is an inherent risk in sales price forecasts (para. 237), and that there is a “subjective” element in expert opinions on the discount rate to be applied (para. 244) are factors which, while they require great care to be exercised in applying the DCF method, in no way suggest that DCF is “not fitted” to the Tribunal's task here. It likewise would be incorrect to suppose that the DCF method was wholly rejected in LIAMCO; as to Petroleum Concession 20, a developed field“! the sole arbitrator awarded $66,000,000 (of 5186,270,000 claimed) “for loss of concession rights” in addition to a separate “indemnification for loss of physical plant and equipment.” LIAMCO, supra, 62 I.L.R. at 212-14, 218. Earlier practice of the United States Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, cited in the Award (para. 230, n. 4), must be understood in light of the fact that the Commission has applied rules municipally legislated by Congress in the special context of lump sum settlements: Any standard, so long as it is uniformly applied to all claimants competing for a “piece of the pie,” will produce just results, comparatively speaking, among them; a standard producing a generally lower rather than a higher absolute entitlement, however, produces a higher percentage of recovery for all from the common fund, a result not without its political satisfactions.

In any event, as Lillich points out, as of 1972, the Commission more recently had been “developing sophisticated evaluation techniques” and, for example, had “adopted the practice of valuing many enterprises at a figure 10 times their average annual net profits after taxes.” 1 The Valuation of Nationalized Property in International Taw 116 (R.B. Lillich ed. 1972). Likewise the Award's reliance (para. 230, n.5) on S.P.P. (Middle East) Limited v. Arab Republic of Egypt, paras. 62-65 (Bernini, Elghatit, Littman arbs.. Award of 16 Feb. 1983), reprinted in 22 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 752, 782-83, is misplaced. The tribunal there awarded “damages (including ‘damnum emergens’ as well as ‘lucrum cessans’).” In doing so it stated its “opinion that an approach to the quantification of damages by means of a discounted cash flow calculation should in this particular case be rejected” because, inter alia “Ibjy the date of cancellation the great majority of the work had still to be done.” (Emphasis added.) In the instant Case, to the contrary, commercial production had long since been achieved.

28 As the Tribunal stated in AMINOIL: [Certain] large transnational groups may have preferred compensation that had no relation to the value of their undertaking, if it was coupled with the preservation of good relations with the public authorities of the nationalizing State with, presumably, resulting prospects for the future giving promise of greater worth than the compensation foregone. AMINOIL, supra, para. 156, 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 1036.

29 The calculation of compensation thus must exclude the possibility of deviation by Iran from the applicable legal norm, whether to accomplish an unlawful expropriation or to act lawfully while failing to grant just compensation. The Award is similarly defective to the extent it would favor the discount rate estimating a higher currency risk based on conduct violating the Khemco Agreement or the Treaty of Amity (paras. 248-249). See Dissenting Opinion of Richard M. Mosk in Hood Corporation and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 142-100-3 (13 July 1984), reprinted in 7 Iran-U.S. C.T.R. 48 (Iranian exchange control legislaTion violated Treaty of Amity); Dissenting Opinion of Richard M. Mosk in Schering Corporation and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 122-38-3 (16 April 1984), reprinted in∼∼5 Iran-U.S. C.T.R. 374 (same).

30 I refrain from discussion of any award of damages additional to the prospective grant of full compensation for the value of the undertaking because (1) the Award excludes the possibility of an unlawful taking; (2) the Claimant does not ask for actual restitution of or any value of its rights beyond what it was as of 31 July 1979; (3) the Khemco facilities on Kharg Island appear to have been destroyed by war, hindering an evaluation of probable post-July 1979 experience; and (4) Claimant has not urged an award of any consequential or punitive damages.