Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

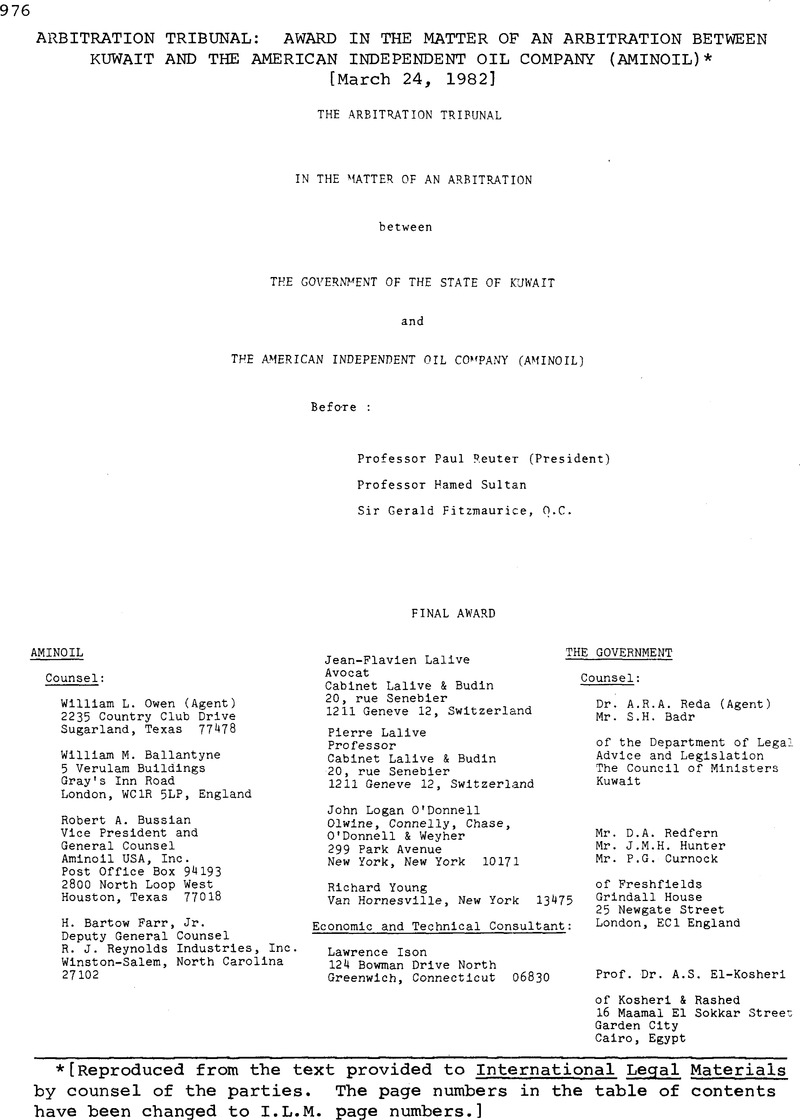

[Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by counsel of the parties. The page numbers in the table of contents have been changed to I.L.M. page numbers.]

1 See Information Department Press Release n° 10-74, Vienna, 13 December, 1974.

2 This is only an approximate description. As regards the group of Companies from which the State had acquired 601 of their issued capital, each Company was allocated 54 cents per barrel in respect of their own remaining 40% share, but nothing in respect of the 60% produced for the State. Thus the total of the mean benefit, i.e. 54x40/100 = 216/10 = 21.6 ” came to 22 cents per barrel to the nearest cent.

3 see Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. XVIII,n° 8, 13 December, 1974.

4 I.C.J. Reports 1969, p. 47

5. Reports of International Arbitral Awards (RIAA) VOl. XII. P.315.

6. RIAA, Vol. II, p. 928.

7. Administrative Tribunal case (ILO and UNESCO), Advisory Opinion of 23 October, 1956, I.C.J. Reports, p. 100.

8 As was recently stated by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in Banco Nacional de Cuba vs. Chase Manhattan Bank. (4 August, 1981), “It may well be the consensus of nations that full compensation need not be paid ‘in all circumstances' ... and that requiring an expropriating state to pay ‘appropriate compensation’ - even considering the lack of precise definition of that term, - would come closest to reflecting what international law requires. But the adoption of an 'appropriate compensation’ requirement would not exclude the possibility that in some cases full compensation would be appropriate”.

1 The Company longed for a stability it was never to receive over payments to the Government. The signature - and solemn ratification by the Kuwait Parliament of the July 1973 Agreement - a very detailed and comprehensive instrument arrived at after painful negotiations - would have given some assurancem of this, though of course no real guarantee of it. Moreover, the July Agreement provided for the introduction by legislation or legislative decree of a regular Kuwait Tax Law. This was important for the Company because, under United States law, it was only on the basis of a legislative obligation to pay Kuwait tax that, by way of immunity from double taxation, exemption could be claimedfrom US tax on the Company's profits. Such legislation was never passed or even presented to Parliament.

2 Except on grounds specifically provided for in the contract itself, it does not lie within the legal entitlement of either party to a contract to terminate it unilaterally, since allegations of fundamental breach or failure of consideration can never - initially and in principle - be more than allegations, because, as a matter of law, it can never lie within the power of one party, acting alone, to make a final determination of such a matter. In short, a party cannot cause a fundamental breach or failure of consideration to occur merely by stating that in its view such is the case. The upshot is that to have even a preliminary effect, such an allegation must be the subject of a notice given to the other party purporting to terminate the contract on grounds stated. Such a notice often has the result of bringing the contract to an end de facto, - but not de jure unless the other party accepts the notice. Failing that, there is a dispute as to whether the grounds given are sufficient, and whether the termination is justified - a dispute that ultimately can only be settled by the decision of a competent tribunal of some kind.

3 With regret, because in my view Aminoil were sufferers from a situation that was not of their making and over which they had no real control. They had few bargaining counters except temporary ones of diminishing value, while all the trump cards were actually or potentially in Government hands. The Parties were never even on that minimum of comparable footing that can alone lead to freely negotiated satisfactory agreements.

4 Article 11(A), whether in its 1948 or 1961 form, was never invoked, and it was not suggested on either side in the course of the proceedings that the cases it specifies have the slightest relevance in the present concession.

5 By which I mean broadly, for present purposes, a nationalisation that is not arbitrary, capricious, basically punitive, or otherwise discriminatory.

6 In my opinion, compensation in this context implies adequacy, or it is not compensation. Strictly, there should be no need to specify that it must be adequate. This still leaves plenty of room for controversy as to what is adequate.

7 By what historical process did provisions such as Article 17 come to be inserted in agreements between States and foreign commercial or industrial entities ? In contracts between private parties they would have been thought quite superfluous. If the contract provided that it was made for a certain period, then it would follow automatically that it could not be terminated unilaterally by either party during, or before the end of, that period, except for reasons specifically provided for elsewhere in the contract. To “spell-out” all this at length would have been thought exaggerated and really somewhat invidious. Again, even in contracts between States and foreign corporate entities, the same view would normally have been taken at any time up to about the date of the first world war. But between the two Wars things began to change. Particularly in Latin-America, there were increasing , cases in which the local government, having granted a concession to a foreign corporate entity for the construction and running of railways, tramways etc., or to extract and process mineral products, would wait until the undertaking had got past its “teething” troubles and had become a “going concern”, and would then step in and take it over. The appellation of “nationalisation” was not then much in vogue, but the effect was the same, namely that the State compulsorily acquired the undertaking, either itself to operate it, or to hand it over to a corporation of local nationality. It was specifically in the light of those occur-, rences that stabilization clauses began to be introduced into concessionary contracts, particularly by American Companies in view of their Latin-American exDeriences, and for the express purpose of ensuring that Concessions would run their full term, except where the case was one for which the Concession itself gave a right of earlier termination.

8 In addition, in the present case, a clearly discriminatory elementv enters in, inasmuch as the parallel nationalisation of the Kuwait Oil Company (KOC) was carried out in agreement with that Company, on terms consented to by it - see Award, Section II, paragraph (li). No such option was offered to Aminoil.