When I first arrived in Svilengrad in June 2016, I found a Bulgarian border town of about 18,000 inhabitants. Its location near Kapitan Andreevo, one of the most crowded border posts of the European Union, seemed to be the town's major source of income and animation. Casinos, forex facilities, and other services aimed at day-trippers from neighboring Greece and Turkey obviously served as the mainstay of the town's economy. Abandoned and gutted silk factories, however, reminded me of the relatively recent economic conditions experienced by the town during the Cold War, when the nearby borders were blocked and when Svilengrad was about as far southeast in communist Bulgaria as a person could conceivably go (assuming you could obtain permission to enter the sensitive militarized border area). Yet other scattered and long-standing historical remnants testified to even earlier periods in history when, during the long Ottoman rule, the town served as the main gateway to nearby Edirne, the Ottoman second capital, now situated across the border in Turkey. Chief among these relics is the imposing 16th-century multi-arched stone bridge (cisr), stretching over 294 meters across the Meriç (Greek: Evros; Bulgarian: Maritsa) River. Built by Çoban Mustafa Paşa (d. 1529), then the governor of Rumeli, it bestowed upon the town its Ottoman name—Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa (the Bridge of Mustafa Paşa)—and its iconic symbol.Footnote 1 The identification of the town with the bridge reflected its location on a major crossroad linking the Ottoman capital with its Balkan provinces. In the words of Kapka Kassabova, who wrote about the contemporary Greek-Bulgarian-Turkish border triangle: “Mustafa Pasha was the name of the bridge and the town, because the town was the bridge.”Footnote 2 Scattered Bulgarian monuments and a modest exhibition in the small local municipal museum recount the town's liberation from the “Ottoman yoke” in the course of the Balkan Wars (Bulgarian rule was established twice over the town, in October 1912 and in October 1913) and commemorate the role of its airfield as the cornerstone of the Bulgarian military's air force.Footnote 3

Svilengrad's population today is completely Bulgarian and has been so since 1913. However, the Ottoman past is still remembered among its inhabitants, many of whom are Bulgarian descendants of refugees who fled to the town from Eastern Thrace following the Second Balkan War. Valentina Gareva-Raycheva, who studied the significance of the border separating Bulgaria from Turkey and its impact on the local populations, found that Edirne still evoked a sense of importance among Bulgarian residents of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa/Svilengrad, extending from the times before the Balkan Wars. For the locals, Edirne was the big market center situated “within hearing distance” of their own town.Footnote 4

The transformation of Ottoman Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa to Bulgarian Svilengrad (meaning Silk City, a reference to the tradition of sericulture in the region) was the outcome of a combination of local violence and state policy throughout the Balkan Wars (1912–13) and within the context of state-building efforts (in both Ottoman imperial and Bulgarian postimperial contexts).Footnote 5 During the First Balkan War (October 1912 to May 1913), a coalition of four Balkan kingdoms—Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro—attacked the Ottoman state, virtually chasing it out of the Balkan Peninsula. Dissatisfied with the division of the conquered territories, Bulgaria attacked its former allies during the much briefer Second Balkan War (July 1913). However, finding itself isolated and under attack by hitherto neutral Romania from the north, Bulgaria was forced to seek an armistice. The Ottoman army capitalized on the Bulgarian evacuation of Eastern Thrace to recapture the area, including Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. Following the conclusion of the peace agreement in September 1913, the Ottomans had to surrender Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa to Bulgaria.Footnote 6

The sequence of mass violence that culminated in the ethnic cleansing that took place during the Balkan Wars stands at the core of this article. The term ethnic cleansing entered into academic and everyday usage only in the 1990s against the background of the wars that afflicted some of the republics comprising Yugoslavia. The term still lacks legal definition. For the purposes of this article, I will use it to mean “a systematic policy designed by and pursued under the leadership of a nation or ethnic community or with its consent, with a view to removing, by means of force and/or intimidation, a population deemed ‘undesirable’ because of its ethnic, national or religious origin.” Footnote 7 Although the violent process of ethnic homogenization and violence against civilians before and during the Balkan Wars was certainly not unique to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, in this article I look for some local political and social distinctions that when combined probably contributed to the level of ethnic violence that engulfed the town and enforced ethnic homogenization. Throughout this period, Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa passed three times between Ottoman and Bulgarian rule. These frequent changes of regime and national agenda had terrible and opposing ramifications on those who were considered outside of the national community. Based on Ottoman, Jewish, international, and translated Bulgarian sources, my primary aim in this article is to present and discuss the everyday dynamics and events that took place in the town by placing them in the context of the macrohistorical transformations generated by the Balkan Wars.Footnote 8 Although the ethnic violence of the Balkan Wars is well documented, the case of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa stands out. For one thing, the town's burning down to the ground and the three violent changes of regime brought about total devastation among the different targeted local communities. The town had to be reestablished, but each regime approached this according to the new criteria of an exclusive national belonging. This required the fundamental reconstruction of the town for the Bulgarian population of locals and refugees by the Bulgarian regime, and the foundation of a new town that would absorb the Muslim refugees on the other side of the border by the Ottoman regime.

Furthermore, the case of the Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa also allows us to explore the role of the local people in determining the future of their town and communities. Each representing their own perceptions and interests, the local communities were the fundamental drivers in determining the future of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. Peter Sahlins's monograph on the creation of the French–Spanish borderland in the Pyrenees and its contribution to the consolidation of the respective national identities is pertinent to our discussion. For him, “state” and “local society” were abbreviations “for different configurations of social and political groups which, acting out of private or collective interests, constructed the boundaries of territory and identity.”Footnote 9 In a similar manner, the peace agreement concluded at the end of the Second Balkan War reestablished Bulgarian rule and provided international endorsement of the total homogenization of the town. At this later stage, I would argue, local perpetrators determined the process of homogenization by initiating violence against their neighbors, sometimes in defiance of formal decisions of the Bulgarian government in Sofia. This defiance may be explained by the social dynamics and realities of the borderland, reflecting the borderland communities' own particular circumstances rather than the policies promoted by the political center and its agents, as discussed by Michiel Baud and Willem van Schendel. According to them, local elites could to a certain degree retain independent power bases that enabled them to pursue their own agendas and oppose state policies. Although most modern borders were created and drawn in state capitals, their exact dynamics and everyday routines were sometimes determined by local communities.Footnote 10 Even after a border had been conceived and delimited, Sahlins underlines that the state's power in the borderland could remain restricted and unstable because of local leaders attempting to use state institutions for their own ends.Footnote 11

To expand upon this phenomenon, I take a close-up look at Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and turn to microhistorical analysis to study the violence perpetrated by local Bulgarians against their Jewish neighbors to deny their possible return to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. Although small Jewish communities were devastated by the Balkan armies during their advance into Ottoman Thrace and Macedonia, it seems that only the community of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa was violently denied its restoration following the reestablishment of peace in the aftermath of the Balkan Wars. Analysis of detailed reports, petitions, and desperate appeals for help that appeared in the local Ladino and international Jewish press enables the delineation of the everyday deeds of communal violence that brought about the community's demise. It equally allows me to discuss several major topics, such as the relations between majorities and minorities and between center and periphery as well as the policies of communal inclusion and exclusion. These sources also permit me to focus on the situation of the Jewish community in relation to the conflict. Although much of the literature on the mass violence and ethnic homogenization that characterized the Balkan Wars deals with the national groups identified with either one of the belligerent states, a discussion of the Jewish community of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa provides a different point of view: that of those minorities whose ethnic affiliation and future citizenship was questioned by both of the belligerent sides.Footnote 12

Finally, the offer of humanitarian aid to “deserving” victims and its denial to others provides another important aspect to defining inclusion versus exclusion. Therefore, I investigate the role of the state and its positioning vis-à-vis transnational and local assistance networks in offering aid to the victims in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. I explore the interplay between national- and local-level factors in both initiating mass violence and assisting its victims during the Balkan Wars.Footnote 13 After all, benefiting from state assistance versus relying on local networks is pertinent because members of the community tend to form their boundaries and define their solidarity by means of the provision or denial of assistance to those who are in need.Footnote 14

The set of sometimes contradictory historical sources, such as those used in this article, suggests different narratives, interpretations, and justifications. Such ambivalent testimony is not an obstacle, however, as my aim is to examine how the different sources promote and legitimize new policies of inclusion and exclusion. Mixed narratives are beneficial because they highlight the points of view and claims raised by different parties in this conflict. Building my discussion on the growing literature that uses microhistorical analysis to explore the identities, motives, and narratives of those who stood behind acts of mass violence, I study the process of ethnic homogenization that took place in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa from both the top-down and bottom-up perspectives. First, I introduce the town and its populations on the eve of the Balkan Wars, as well as the major military and political events that had a direct impact on the town. I then move to analyze the impact of the First Balkan War and the ensuing Bulgarian occupation of the town on its demographic reconfiguration. The panicked flight of much of the Muslim population (but also of Greeks and Jews) and the atrocities committed by the Bulgarian army and local irregulars against the remaining Muslims dominated the Ottoman and the international coverage of the First Balkan War. The Second Balkan War and the temporary reinstatement of Ottoman rule over the town reversed the situation, as the Bulgarian civilians of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa (and elsewhere in Eastern Thrace) took their turn in enduring the rage of the Ottoman authorities. In this part of the article, I turn my focus onto Bulgarian and international accounts regarding the return of Ottoman rule, and I will present testimonies on Ottoman atrocities performed by the army with the support of local Muslims. The signing of the peace accords putting an end to the hostilities between Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire in September 1913 signified a new stage in the demographic engineering of the town's population, as it sanctioned and finalized the “organized,” state-sponsored exchange of populations. The ostensibly opposed discourses of assistance and reconstruction dominated the scene. For the Kingdom of Bulgaria, this meant the accommodation of Bulgarian refugees arriving in the city from the adjacent areas in Eastern Thrace. For the Ottoman Sultanate it entailed the construction of a new town: Yeni [New] Mustafa Paşa, to settle the refugees coming from the other side of the new borderline separating the Ottoman Empire from Bulgaria. Taking advantage of the still blurred boundaries separating Greeks from Bulgarians, local Greeks could still negotiate their position and choose between assimilation and emigration to Greece.

Yet, even at this stage, the prevention of Jewish citizens’ return to the town by their Bulgarian neighbors and the community's resulting demise highlight both the crucial role played by local actors, many of them members of the Internal Macedonian Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO), established in Salonica in 1893, and of the similar and newly established Macedonian Adrianople Volunteers, an independent military unit that was organized by the Bulgarian army at the beginning of the First Balkan War, in harassing their erstwhile neighbors and displacing them from their homes and properties.Footnote 15 Alp Yenen and Ramazan Hakkı Öztan describe the turn of the 20th century in the Ottoman Empire as “the Age of Rogues,” highlighting the role of parapolitical and paramilitary agents, such as members of IMARO, in initiating violence and aggression in many parts of the Ottoman borderlands. Harboring different political, social, or personal motives and interests, the aim of these “rogues” was to cause upheaval to the legitimate existing norms of politics and the formal institutions that hitherto defined Ottoman sovereignty. With the absorption of new types of ideologies, tools, and repertoires in the second half of the 19th century, such “rogues” emerged on the Ottoman frontiers “where the local struggles could become part of the global, and the global might connect with the local.”Footnote 16

The article, therefore, utilizes macrohistory and microhistory to analyze the demographic upheaval of Thrace during and after the Balkan Wars. In the context of this first major European war of the 20th century, the shift from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa to Svilengrad can enhance our understanding of intercommunal violence. Scholars of mass violence and ethnic cleansing in the late Ottoman Empire and under the young Turkish Republic are using this approach increasingly to discuss the roles of the state (both Ottoman and Bulgarian) and of local players in the process of “cleansing” Thrace during the early 20th century. Although it is evident that in both cases much of the violence was state-sponsored, or, at the least, tacitly accepted by the state, and reflected top-down planning, nonstate players also took part in the retribution against those they deemed alien to their national cause.Footnote 17 Shaping his argument around the growing literature on comparative genocide studies and theories of bottom-up approaches, Uğur Ümit Üngör highlights the role of local elites in the process of mass violence. According to him, “it is often the local elites who initiate the first phase of persecution and afterward a certain radicalization develops from the interplay of center and periphery.”Footnote 18 Analyzing the events that triggered the so-called Thrace 1934 pogroms, Berna Pekesen claims that macrostructural interpretations, such as nation-building, modernization, and structural violence, “run the risk of over-generalizing and thus supporting an idea of history as a one-way road. Ideally, they ought to be combined with a micro-structural approach that enables insights into local conditions, local actors, and situational factors.”Footnote 19

Accordingly, the study of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa/Svilengrad during the Balkan Wars can assist us in better understanding the state's and local actors’ roles in homogenizing the town's population.

The Location: Late Ottoman Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa

Being a transportation hub and a border town defined Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa at the turn of the 20th century. Prior to the Balkan Wars, it was the center of a subdistrict (kaza) under the jurisdiction of the Edirne Province (vilâyet) and district (sancak). The granting of autonomy to the Principality of Bulgaria following the Ottoman–Russian War of 1877–78 turned the multiethnic and multireligious Edirne Province, like some other parts of the remaining Ottoman provinces in the Balkans, into a borderline zone plagued with competing national and irredentist aspirations vying for influence and control. Subsequent to the de facto retracing of the Ottoman-Bulgarian border following the unilateral unification of the Principality of Bulgaria with the Ottoman autonomous province of Eastern Rumelia in 1885, Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa became a border town. The Ottoman authorities maintained a military and bureaucratic presence in the town. Furthermore, the newly created border between Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire did not represent merely an international crossing point between two countries. During the following decades and until the outbreak of the Balkan Wars, it witnessed the growing separatist and military activities of the IMARO organization and the communal tensions between local Turks, Bulgarians, and Greeks.Footnote 20

Being the first Ottoman railway stop for those traveling to Istanbul from Bulgaria (fully independent as a kingdom since 1908) and beyond, and its proximity to Edirne, the provincial center, rendered Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa a frequent stop for both Ottoman and international visitors. In 1910, Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria (r. 1908–18) arrived there by train at the beginning of his official visit to Istanbul. He and his entourage had to wait for several hours in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa before continuing their journey to the Ottoman capital. This was just a technical stop necessitated by the different railway systems. His first official reception took place in Edirne, where the Bulgarian anthem was played in honor of the Bulgarian royal delegation.Footnote 21

As a small town, late Ottoman Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa rarely appeared in the memoirs literature. One exception was the writing of one of its most (in)famous Muslim sons: the philosopher and poet Rıza Tevfik Bölükbaşı (1869–1949), who is chiefly remembered today in Turkey as one of the four Ottoman signatories of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920). In his memoirs, he referred to his town of birth in the following words: “Each time I recall that I was born in the government building of Cesir [sic] Mustafa Paşa, on the shore of the Meriç River, I find myself claiming: ‘O Man! . . . Could you not find another place to be born?’”Footnote 22

Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa was part of the province of Edirne, and the province's salnames (yearbooks) offer some demographic and administrative information about the town (kasaba). The provincial authorities in Edirne began publishing such yearbooks in 1870 in an attempt to better control and administer the province. According to the salname of 1317 (1901), there were 12,910 Bulgarians, 10,432 Muslims, 4,325 Greeks, 417 Jews, 35 Armenians, and 89 Catholics living in the subdistrict of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. Together, the subdistrict's population numbered 28,208 people.Footnote 23 Contemporary Bulgarian data, expressed in household units, suggest slightly different numbers. Prior to the Balkan Wars, the town was comprised of 6,053 families, of which 3,971 were Christians, 1,983 were Muslims, 80 were Jewish, 10 were Uniates, and 10 were Armenian.Footnote 24 The town's educational system provides some additional insights into the demographic composition of the town. The state schools that were attended mostly by Muslims recorded the following number of pupils: the secondary (rüşdiye) school had 25 students, and the primary (ibtidai) schools had 140 boys and 105 girls. The Greek school catered to 60 boys and 45 girls, whereas the Bulgarian school had 326 boys and 166 girls among its pupils. The Jewish school had 90 boys and 42 girls.Footnote 25 Although the non-Muslims comprised a clear majority in town, a certain Muslim named Ahmed Bey served as the mayor in 1901.Footnote 26

Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa boasted two Friday mosques, one newly constructed by Sultan Abdülhamid (r. 1876–1909); the other was much older. Haseki Sultan, the favored wife of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent and probably the most famous female benefactor of the Ottoman 16th century, had donated the funds for the construction of the old mosque. In addition, there were two neighborhood mosques. Administrative and military establishments included a recently built government building (konak), a military compound that could accommodate eight infantry battalions (tabor) and two cavalry regiments (alay). The town harbored a small military hospital, a telegraph post, a post office, a quarantine facility, a municipal building, a branch of the state-owned Ziraat (Agricultural) Bank, and a gendarmerie barracks. In the entire subdistrict, there were twenty-three churches and one synagogue. Other properties included five hundred thirty-six shops, three public baths, eighty-nine mills, thirty coffeehouses, fifty-five taverns, two hotels, and fourteen inns. Each village had its own mekteb (Muslim traditional school).Footnote 27 Ottoman archival sources from the turn of the 20th century often relate to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa's position as a border town. One example is provided by the correspondence regarding the construction of a quarantine building that was intended to receive travelers originating from Europe.Footnote 28 A short newspaper article reminded those travelers on the way to Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia that qualified translators worked in the registry office (nüfus idaresi) in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, who could provide them with a last-minute in situ translation of their travel documents into French.Footnote 29

According to the Ottoman salname, Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa was spread out, sparsely populated, and surrounded by vineyards and orchards benefiting from temperate weather and plentiful water.Footnote 30 This somehow docile description of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa clearly omits the growing ethnic and religious tensions and clashes that engulfed Ottoman Thrace and Macedonia in the decades that preceded the Balkan Wars. Although the Ottoman yearbooks are indispensable as a source for understanding the town's demography, administration, and infrastructure, they are of limited use for understanding the communal relations and conflicts in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. The local Bulgarian majority living in the town were not indifferent to the rising Bulgarian nationalism behind the adjacent border in Bulgaria, nor to its ramifications for their own identities and affiliations. Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, as other parts of Ottoman Macedonia and Thrace, became a “rebellious borderland,” where some of the local Bulgarian and Greek leaders and populations defied Ottoman rule while engaging in conflict with each other and with the Muslim population.Footnote 31 Many of the events took place in the major cities, such as Salonica and Edirne, where Bulgarian educational, ecclesial, and media infrastructure was gradually developing in sharp conflict with competing national ideologies. Military activities occurred mostly in the mountainous and less accessible areas of Macedonia. For its part, Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa played only a small role in these events, and therefore its local agents are scarcely mentioned in the academic and Bulgarian commemorative literature. Nevertheless, some leading figures of the Bulgarian national movement temporarily sojourned in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. One such example was the author Ivan Vazov (1850–1921), often referred to as “the patriarch of Bulgarian literature,” who taught in the local boys’ school in the autumn of 1873.Footnote 32 Consequently, the Bulgarian national cause gained local supporters. Among them, one family of three generations stands out: the Razboynikov family.

Born in Harmanli, Bulgaria, to a family from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, Anastas Razboynikov (1882–1967) is probably the family's best known member. He compiled the main local history of the town up to 1913 in Bulgarian. Although one scholar defined him as an “unknown” revolutionary, his book and other publications on local history, ethnology, and geography enable us to retrace the family's role to the Bulgarian cause in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa.Footnote 33 His grandfather, Anastas Stankov Razboynikov, was one of the founders of the Bulgarian ecclesial and educational infrastructure in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and served as a priest and then bishop at St. Troitsa (the Holy Trinity church constructed in 1834) in the town for almost fifty years. The first Bulgarian secular school was founded in 1847 next to the church building. Anastas Razboynikov's father, Spas, was engaged in beekeeping and silk farming, like most Bulgarian residents of the city at that time. More pertinent to our discussion is the father's nomination as the first Bulgarian mayor of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa following the Bulgarian takeover in 1912, a clear indication of his prominent position in the local community.Footnote 34

Bulgarian nationalism left an undeniable impact on Anastas Razboynikov's identity and activities. In 1902 he completed his secondary education at the Bulgarian Dr. Petar Beron high school located in nearby Edirne. This institution functioned as a major center for mobilizing Bulgarian youth to join the IMARO organization.Footnote 35 Young Anastas Razboynikov joined this paramilitary organization during his high school studies. His main activities during these years were the distribution of national literature, serving as a courier maintaining connections between different members of the IMARO in the Edirne region, and pursuing some basic military training. He was recommended by the IMARO revolutionary committee in the Edirne district, and the Bulgarian Exarchate nominated him as a head teacher in nearby Bunarhisar (nowadays Pınarhisar in Turkey), where he endeavored to promote the organization's activities. Facing imminent arrest, he fled in 1903 to the mountains and joined a military squad of Yasna Polyana inside Bulgaria. He turned his new shelter into a base from which he promoted his political and military activities in IMARO. Following the Ottoman oppression of the Ilinden (or St. Elijah's Day) Uprising in the summer of 1903, “the only episode of open rebellion in Ottoman Macedonia that featured the participation of around 20,000 armed rebels,” in which Razboynikov took part, and yet another short sojourn in Bulgaria, he returned to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa to assume teaching work again.Footnote 36 In the following years, he moved between the centers of Bulgarian activity in Ottoman territory, Edirne, and Salonica, engaging in educational work, academic research, and journalism. At the beginning of the First Balkan War, he was working as a teacher in the Bulgarian high school in Salonica and as one of the publishers of the Bulgarian newspaper Bulgarin.Footnote 37 The outbreak of war and possibly his father's nomination as mayor brought him back to Cisri-i Mustafa Paşa, where he witnessed some of the events that will be discussed later in this article.

What we can discern from the cultural, political, and paramilitary activities of the various members of the Razboynikov family follows. First, they closely represent each of the major phases of Bulgarian nationalism as they unfolded in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and the neighboring areas. Whereas his grandfather played a role in the local manifestations of the establishment of the Bulgarian national church, the Exarchate, Anastas Razboynikov was a local member of the IMARO organization. Taking advantage of his profession as a schoolteacher, he moved between different localities contributing to the organization's cause. The cross-border mobility of Anastas while a member of IMARO organization and his ability to cross the international border into the mountains in Bulgaria whenever he felt threatened underscores the border's porosity in the decade that preceded the Balkan Wars. It also suggests the existence of cross-border networks and webs of loyalty that benefited Bulgarian (and probably other) clandestine activists. The location of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa on the border facilitated such networks that reached across the international borderline.

Before the outbreak of the Balkan Wars, Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa was a mixed provincial town with a clear Bulgarian majority. Most of the inhabitants of the town and the surrounding villages were Bulgarians and Greeks. For Kâzım Karabekir, who served as a staff officer in the Ottoman 10th Division, responsible for defending one of the fortifications surrounding Edirne, this fact posed a constant threat. In his memoirs, written during his captivity in Bulgaria, he mentioned that prior to the outbreak of the Balkan Wars he had assumed that the Greeks and the Bulgarians in the town would assist the Bulgarian army in the case of war.Footnote 38

Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa during the First Balkan War: Turning the Town into a Bulgarian National Icon

In its military planning, the Bulgarian General Staff recognized the significance of the Edirne region to the outcome of any possible war against the Ottomans. Due to the region's proximity to the Ottoman capital, they assumed that such a war “would be won and lost in Thrace.”Footnote 39 Indeed, a French newspaper described Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa as the “key to Thrace.”Footnote 40 On October 18, 1912, the first day of its offensive, the Bulgarian army broke through the scattered Ottoman border forces and entered Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. It was the first Ottoman town to fall into Bulgarian hands. A report sent from Edirne to the headquarters of the Ottoman Eastern Army announced that the famous bridge on the Meriç River and all bakeries had been destroyed prior to the evacuation of the town. Actually, the 16th-century bridge appears to have been only marginally damaged, as a Bulgarian cavalry unit was able to cross it on their way into the town.Footnote 41 The Ottoman-Armenian historian, Aram Andonyan (1875–1951), left a detailed description of the first day of combat, during which Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa was taken by the Bulgarians. Taking advantage of the disordered Ottoman retreat from the border posts, the advancing Bulgarian Second Army captured the town. The Bulgarian booty included some old canons and 200 tons of wheat and rye. The Bulgarian army immediately continued its march toward Edirne.Footnote 42

Unlike the following major Bulgarian offensives in Thrace, the capture of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa did not involve tremendous military activities. The defending Ottoman border forces were too few and dispersed to offer much resistance. Reporting from Sofia, the then military correspondent for a Russian-language newspaper, Leon Trotsky, reported on the indifference that many Bulgarians felt when hearing the news about the conquest of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. For them, this was merely a border skirmish.Footnote 43 However, their disregard quickly changed as Bulgarian propaganda crowned the town as the first piece of land to be liberated from the “Turkish yoke.” For a while, the town became a destination for official visits and a site for building plans. The Bulgarians celebrated their military achievement with an array of national ceremonies and the production of a range of memorabilia commemorating the event. As a token of its symbolic significance, the new Bulgarian administration renamed the town Ferdinandovo (Ferdinand's Place) in honor of the incumbent Bulgarian tsar.Footnote 44 Soon thereafter, the tsar paid tribute to the town with an official visit. An anonymous photographer captured the victorious image of Tsar Ferdinand marching in the main street of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa.Footnote 45 Accompanied by military officers, he strode behind senior priests holding religious regalia. Bulgarian tricolor flags adorned the surrounding buildings (Fig. 1).Footnote 46 The public humiliation of the enemy played a part in these theatrical manifestations. The intended audiences were both the Bulgarian public and the international community. The Parisian journal, Le Petit Journal, provided a picture on the back cover of its illustrated supplement showing the Bulgarian tsar stepping on Ottoman flags and standards lying on the ground. The title cynically read, A Curious Bulgarian Custom (Une curieuse coutume bulgare).Footnote 47 This triumphalist image also appeared on Bulgarian postcards.Footnote 48

Figure 1. King [of] Bulgaria entering Moustapha Pacha [1912?], Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain News Service Photograph Collection, LC-B2- 2483-3 (P&P), http://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/2515737727.

Bulgarian war propaganda used the town's image to herald the new horizons opened for the Bulgarian nation. It issued a postcard to memorialize the territorial gain. Entitled “Greetings from the Aegean Sea,” it displayed a map of the border areas between Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire presented as mountainous landscape bordered by the Black Sea in which a boat named Bulgaria was cruising forward with the rising sun in the background. A Bulgarian soldier is seen proudly standing with one foot treading on a circle representing Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, his gun leaning on the Bulgarian city of Plovdiv. The accompanying caption announces: “A souvenir from the first post of conquered Turkish territory (Fig. 2).”Footnote 49

Figure 2. “A souvenir from the first post of conquered Turkish territory.” Author's private collection.

Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa turned into a major site for official visits. Tsar Ferdinand's short visit with his general staff to the town encouraged the military authorities to clear the major streets of the ubiquitous mud and transport wagons. Standing on the town's famous bridge over the Meriç River, the tsar shared his thoughts about the beauty of the surrounding countryside, “perhaps one of the most beautiful views in the world,” as well as of the upheavals of history.Footnote 50 Indeed, Bulgaria had big plans for this area; it was determined to keep the Meriç River within its borders. It envisioned publicly that the river would become navigable along its full course and enable Bulgaria to connect with Dedeağaç (now Alexandroupoli), the only port on the Aegean Sea that Bulgaria was able to secure after the Balkan Wars (following its defeat in World War I, Bulgaria was forced to cede Dedeağaç as part of Western Thrace to Greece).Footnote 51 The new rulers of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa proudly displayed their plans to turn the town into a major Bulgarian economic and modernized urban center. The town's capture served to highlight their civil and military superiority over their humiliated Ottoman enemy. The claiming of the town during the First Balkan War as a major symbol of putative Bulgarian modernity and as a springboard for the coming Bulgarian territorial expansion, I would argue, provides us with an important clue to understanding the process of making Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa a homogeneous Bulgarian town.

The First Stage of Ethnic Homogenization: Atrocities and Panicked Flight

As Bulgarian propaganda celebrated the Bulgarian capture of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and highlighted its contribution to the fulfillment of the Bulgarian national vision, the local non-Bulgarian populations were completely ignored. Actually, these were among the first refugees of the Balkan Wars, as they panicked, trekking away in gloomy caravans in search of shelter. For those fleeing Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, shelter and sustenance often meant taking refuge in the nearest big city's military garrison, in Edirne. The bureaucrat, politician, and future mayor of Edirne (1918–20), Dağdevirenzâde Mustafa Şefket Bey (1863–1931), recounted in an entry in his memoirs dated 18 October 1912 that following the Bulgarian attack the Muslim inhabitants of Cisr-i Mustafa and the surrounding villages began fleeing toward Edirne. Marching on foot or using wagons they formed caravans of refugees.Footnote 52 Anastas Razboynikov related that, prior to the Bulgarian army's entry into the town, panic reigned among local non-Bulgarians. The military officers and their families departed first. Following them, local Turks, Jews, and some Greeks were seen fleeing to Edirne. He described the chaos and general confusion that prevailed in the local market when Muslims and Jews, including children, left town without even taking their belongings. The town emptied, except for the local Bulgarians, who stayed put and continued to operate their shops.Footnote 53

In the days following, as Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa was deserted by most of its non-Bulgarian inhabitants, Ottoman sources testify to cases of terrorization and harassment of those non-Bulgarians who remained in the city and looting of the property left behind. At this stage, when Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa was under Bulgarian rule, Ottoman accounts relied on information gathered in Istanbul, to where some refugees and soldiers had fled. The Edirne-born Mehmed Şeref (Aykut, 1874–1939) published a series of articles on the battles of still besieged Edirne in Tanin (The Echo), the organ serving as the mouthpiece of the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP; also known as the Young Turks). These articles, published in January and February 1913, testified to the horrors that befell the Muslims of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and its environs upon the town's evacuation by the Ottoman forces. The Bulgarian irregulars (komitacıs, as the Ottoman called them) were the first to arrive in the town. They did not spare the lives of women, children, or the elderly in the neighboring village of Çirmen (now Ormenio), torturing them to death in a manner “unknown even to Torquemada, the inventor of the Inquisition” before setting fire to the whole village.Footnote 54

In the book İntikam (Revenge), a certain Dr. Cemil provided some details of the brutalities that took place during the Bulgarian occupation. His descriptions only referred to those that targeted Muslims, such as the killing of more than 200 old men, women, and children and the bayoneting of sick and wounded POWs.Footnote 55 He constantly referred to photos and official reports, especially those issued by European journalists and witnesses, to increase the credibility of his claims.Footnote 56 The Jewish press reported on the deliberate burning of the deserted Jewish neighborhood by Bulgarian irregulars, as will be described.

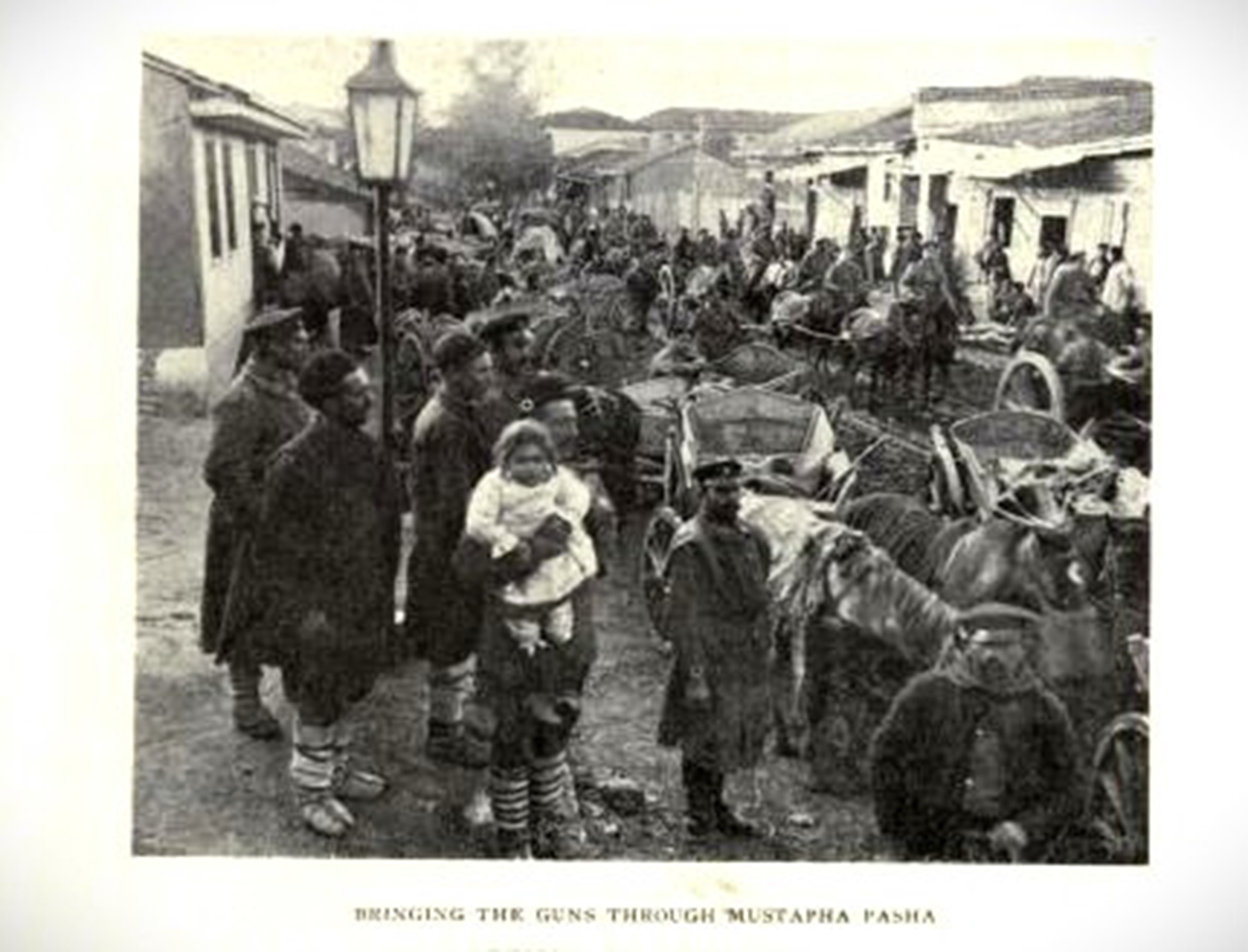

To retrieve the everyday events of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa during the first Bulgarian rule over the town, we need to turn to foreign sources. During the long Bulgarian siege of Edirne (October 1912 to March 1913), Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa remained an important transportation and military base, serving the Bulgarian army and its Serbian allies by reinforcing the blockade of Edirne (Fig. 3).Footnote 57 The concentration of military forces and the closeness of the military front offered unprecedented international exposure to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa as military correspondents representing major Western newspapers flocked into the town and made it their base. The British journalist, Philip Gibbs (1877–1962), working for The Graphic, a weekly illustrated newspaper, arrived in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa at the end of October 1912, several days after the town was captured by the Bulgarian army. When the Bulgarian censors expelled him from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa for violating their instructions, he was not alone. He shared the train ride back to Stara Zagora, inside the borders of old Bulgaria, with another thirty-one journalists.Footnote 58 For a while, the town served as a major international media center.

Figure 3. “Bringing the guns through Mustapha Pasha.” Bulgarian units marching through Mustafa Paşa on their way to besieged Edirne. Phillip Gibbs and Bernard Grant, The Balkan War: Adventures of War with Cross and Crescent (Boston: Small, Maynard, 1913), 18, https://archive.org/details/balkanwaradventu00gibbuoft/page/18/mode/2up.

Philip Gibbs arrived in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa to report on the Bulgarian preparations for the siege of Edirne. However, he did not ignore their looting and devastation of the town. Staying for several weeks in a deserted farmhouse, “barn as it was,” on the outskirts of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, he was able to report on the devastation that the war brought to the inhabitants of this “once prosperous little Turkish town” and that had become “little better than a mud-heap.”Footnote 59

It seemed deserted by all its former inhabitants. Many of the houses seemed to have been broken by some earthquake. Those still standing had been stripped bare. Little gardens, which once perhaps had been beautiful with flowers and trailing plants, had all been ruined and trampled down. Soldiers were camping on bare boards in the houses once belonging to Turkish notabilities, surrounded by their baggage. The Mosque, where many prayers had gone up to Allah, had been filled with sacks of flour and other stores.Footnote 60

Gibbs observed that Bulgarian soldiers occupied most of the houses abandoned by Turks. Others crowded around campfires outside the mosque.Footnote 61 He witnessed peasants, men and women, roaming between the deserted shops and muck heaps in constant search of loot. The Bulgarian military police, he noted, used force to chase them away. He was himself able to “capture” a Turkish flag and a dainty fez spangled with tin. This was his military bounty.Footnote 62 Walking in the town's main street, Gibbs was an eyewitness to the hanging of two Turks in the backyard of a deserted house. Someone in the small “cheerful” crowd informed him that these Turks were responsible for killing Bulgarian civilians and soldiers. One of the Bulgarian guards hacked down some of the boughs enabling the European journalists to take better pictures of the execution.Footnote 63 The execution turned into a public spectacle to be seen and documented.

Probably this same image capturing the execution of two Muslims in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa is the one referred to by Dr. Cemil when he described the Bulgarian atrocities that took place in the town. He mentioned that although he came across this photo in one of the publications distributed by the Association for the Benefit of Muslim Refugees from Rumelia, it had initially been taken by the foreign press. Reminding his readers that he had previously served in the local town administration, Dr. Cemil claimed that he knew these two men personally.Footnote 64 For Leon Trotsky, these same executions reflected the horror of the Bulgarian atrocities. In a polemical letter that he sent to the Bulgarian poet P(etko) Todorov (1879–1916), he bemoaned the “senseless, causeless ‘execution’ at Mustafa-Pasha.” For him, these were merely “a devils’ game by idle officers.”Footnote 65

With the Bulgarian occupation of Edirne in March 1913, Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa returned to its previous role of a stop on the way to Edirne. Louis Ronzevalle (1871–1918), a Jesuit monk and a professor of Arabic at the University of Saint-Joseph in Beirut, reported in Al-Machriq (The East), a Catholic monthly published in Arabic in Beirut, on his trip to Edirne under Bulgarian rule. Born in Edirne, he knew the town and its surroundings well. He mentioned only a short stop in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa's train station “where previously the Bulgarian Army was camping during the siege over Edirne.” He elaborated much more about his emotions as he approached the theater of war in Edirne.Footnote 66 Rabbi Dr. Mordechai (Marcus) Ehrenpreis (1869–1951), the Chief Rabbi of Bulgaria during the Balkan Wars, passed through Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa during his visit to Edirne. In his memoirs, he referred only in passing to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, mostly mentioning the cholera outbreak that raged in the town at the time. While waiting for a train that would take him back to Sofia, he did not dare to venture outside of the town's railway station. He and a fellow journalist spent the night on two field beds in a vacant room with the knowledge that approximately 300 cholera patients were being held in two buildings only 50 meters from the railway station, which did very little to alleviate his fears.Footnote 67

The Second Balkan War and the sudden and hasty Bulgarian retreat from Eastern Thrace (July 1913) enabled the Ottoman army to retake the area, including Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. It allowed the Ottoman press to unearth testimonies of the massacres that took place in the area during the First Balkan War and under the intervening Bulgarian rule. As in other parts of Eastern Thrace, military reports published in the Ottoman daily press provided details of Bulgarian atrocities toward Muslims and Greek civilians even in the final days of the Bulgarian occupation.Footnote 68 As part of a survey of the Bulgarian atrocities that took place in Eastern Thrace during the occupation, a report on Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa appeared in the Tanin edition of August 10, 1913. A reporter, who had arrived in the town about a week after the Ottoman entry into the town, described the situation in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and shared his findings with the readers. For him, the conclusion was clear: the difference between the Ottoman behavior in the town and the ferocious Bulgarian attitude toward its non-Bulgarian inhabitants could be characterized as being the same as that between benevolence (asalet) and barbarism (galatat).

The Tanin reporter saw Bulgarian atrocities everywhere. Already en route from Edirne to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, he saw the once fertile land nourished by the abundant waters of the Meriç turned into a desert with only patches of dried grass for covering. The gloomy vestiges of the war and the desperate faces of the villagers staring at the piles of stones that were once their homes and villages prepared him for his encounter with Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa itself. The Bulgarians had departed the town hastily; one could see their laundry abandoned at the hospital. The locals provided him with some further information: before the outbreak of the Balkan Wars, Greeks and Jews worked in commerce, whereas the Muslims and Bulgarians made their livelihoods from agriculture. All the Muslims fled at the beginning of the war, with no households remaining in the Muslim neighborhoods. The reporter found only ruins in the Muslim parts of the town. Therefore, the returning Muslims now had to sleep in the open air near the well-built Bulgarian neighborhood. Soldiers and gendarmes defended the Bulgarian neighborhood and provided its remaining inhabitants with security. The Bulgarians had also demolished and looted the homes and shops belonging to the Greeks. An old Greek recounted his misery during the Bulgarian occupation, enabling the reporter to understand the Greeks’ warm welcome of the returning Ottomans in Edirne. He saw a pile of stones next to the rüşdiye school; this wreckage, he was informed, used to be the Jewish synagogue and school, yet further proof that the Bulgarians had been determined to demolish every holy site belonging to other religions.Footnote 69

The Return of Ottoman Rule and the Targeting of the Bulgarian Civil Population

The Second Balkan War temporarily brought the Ottoman army back to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. Old routines slowly returned to the town. Some royal visits, this time of the Ottoman sultanic family, took place. The Ottoman press reported that the Ottoman crown prince, Yusuf Izzuddin Efendi, and Prince Ziaeddin, the incumbent sultan's eldest son, honoured Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa with a short visit as part of their festive tour of liberated Edirne.Footnote 70 Such a high-ranking visit underscored the Ottomans’ intention of keeping the town within their borders. The Ottoman Ministry of the Post, Telegraph and Telephone announced at the beginning of August 1913 that a local office had begun operating in the town, albeit with a limited scope.Footnote 71

Clearly, at this stage, the Ottoman narrative highlighted the shared suffering of all non-Bulgarians, and their unanimous wish to see their town remain under Ottoman sovereignty. At the beginning of September, an ostensibly spontaneous public gathering (miting) was held by the local leaders of the town's various Muslim, Greek, Jewish, and Bulgarian communities, to announce their deep attachment to the Ottoman state. As was done elsewhere in Eastern Thrace, the gathering concluded with a set of decisions that strongly protested any attempt to return their town to the “bloodthirsty” Bulgarian administration. Such a move, they claimed, would fly against the principles of the 20th century. The inhabitants of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa declared that they would strive to repel such a step “until the last breath.” Should they fail to achieve their goal, those who remained alive would all leave their place of birth and emigrate. However, they implored to be left under the aegis of the Ottoman government.Footnote 72

Even if this expression of loyalty were written only to conform to the expectations of the reinstated Ottoman administration, it could still reflect genuine concerns. The inclusion of the Bulgarian community in the declaration testifies that some Bulgarians remained in the town at this stage. Tanin quoted at the beginning of August the firm orders given by the governor of Edirne regarding the safety of those Bulgarian inhabitants who fled their town and might choose to return. As the governor was about to visit the town, he ordered that those Bulgarians who decided to return to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa be treated well and that their lives and property be secured.Footnote 73 Yet the atmosphere in the small town continued to be fragile and tense. The Istanbul Ladino-speaking journal El Tiempo reported on August 11 about a local incident that caused much panic. According to this report, a fire broke out in a house belonging to a Bulgarian and caused the explosion of seventy bombs. The anxious population was alarmed and some of them fled the town to Edirne. The Ottoman governor tried to calm the population down and assured them that there was no danger.Footnote 74

Nevertheless, the reinstituted Ottoman rule was only transitory. According to the peace agreement signed with Bulgaria in September 1913, the Ottoman army was required to retreat from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and allow the Bulgarian army to reinstall Bulgarian sovereignty over the town. Consequently, the Bulgarian army returned to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa at the beginning of October. According to Bulgarian sources, before its second and final retreat in September 1913, the Ottoman army executed a scorched earth policy. Stefan Kaimakov quotes Bulgarian sources claiming that due to its strategic location the Turkish army wanted to destroy the town and set it on fire. Windows, doors, and even bricks were looted and taken to Edirne and to Virantepe, the place where they began to build Yeni Mustafa Paşa (today Kapitan-Andreevo in Bulgaria). The Turks, Greeks, and Jews also moved to Edirne.Footnote 75 As part of its commission of inquiry, the Carnegie Endowment published a report written by a local Bulgarian, Alexander Kirov, claiming that the Ottomans carried out a massacre of the local male Bulgarian population.Footnote 76 In his testimony, he recounts that at the beginning of November 1913, the Ottomans’ return during the second war was signaled by the massacre of the entire remaining male population (eighteen persons). An old woman who survived that appalling day described how they were killed one by one amid the laughter and approving cries of the Muslim crowd.Footnote 77 Lina Gergova has studied the settlement of Bulgarian refugees from Eastern Thrace in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and the reconstruction of the town following the Second Balkan War and its annexation by Bulgaria. She found that, according to Bulgarian sources, it was the Ottoman army that burned the town to the ground. The town had to be reconstructed anew.Footnote 78

From Massacres to a Formal and A Posteriori Ratification and Endorsement: The Second Stage of Ethnic Homogenization

The population exchange between the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria following the Balkan Wars was the first case in which the Ottoman Empire internationally legitimized the forced emigration of some of its citizens to a foreign country. Erol Ülker claims that compulsory transfer, based on population exchange, was the first method implemented by the Ottoman government to evacuate the Christian population from the border and other sensitive areas. Formulated in the peace treaty that was signed between the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria after the Second Balkan War on September 29, 1913, the ostensibly voluntary population exchange resulted in the deportation of 48,570 Muslims from Bulgarian territory and 46,764 Bulgarians from the Ottoman Empire's Thrace region.Footnote 79

The case of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa/Svilengrad indicates that when the peace agreement was concluded, the exchange of populations was near a fait accompli. Both sides tried to finalize the new reality. For the Bulgarian side that meant the reconstruction of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, renamed Svilengrad in 1922 (one scholar found that the Ottoman name was “particularly offensive” to the Bulgarians).Footnote 80 Due to its location on the new Bulgarian-Ottoman border, it served as a “migration spot” for Bulgarian refugees leaving Eastern Thrace, many of whom settled in vacant plots from which the previous owners had fled.Footnote 81

For the Ottoman side, it meant construction of a new town aptly named Yeni (New) Mustafa Paşa. Its construction was part of an ambitious project of Hacı Adil Bey, the reinstated Ottoman governor of Edirne, aiming to repopulate the province with Muslim refugees who fled the lost Balkan provinces. The goal was to homogenize this sensitive border area by increasing its Muslim population and by forcing its Christian population to leave the area. Much of what we know about this town is gleaned from pertinent press reports and interviews and official correspondence. Its construction as a new Ottoman town remained very much on paper, as only two years later, in September 1915 and under German pressure, the Ottomans were required to transfer Yeni Mustafa Paşa, as well as some other adjacent territories, to Bulgaria to entice it to join the Central Powers.

The local government's Edirne newspaper announced in late January 1914 the imminent completion of the buildings to serve the state administration in town.Footnote 82 This was probably too optimistic, because five months later the Ottoman Ministry of Internal Affairs sent a memorandum about the need to confiscate private land to build the infrastructure of the new Yeni Mustafa Paşa, established on the other side of the separation line facing old Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, which remained “among those forsaken places.” The planned initial construction included a bridge, government offices, and a school.Footnote 83

The discussion about the new town provides us with some insights into the attempt to present it as a solution for those Ottomans who originally fled from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. Especially telling is the way the governor, Hacı Âdil Bey, defined those refugees in an interview given to Tanin at the beginning of October 1913. He chose to open with a reference to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and neighboring Ortaköy (now Ivalyovgrad in Bulgaria), which, according to the Istanbul peace agreement, had to be returned to Bulgaria. According to the plans, he assured the journal's readers that it had been decided to construct a new center for the kaza about twelve kilometers from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, and that the new locality would bear the same name. Therefore, he claimed, regarding Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa's previous function as the center of a kaza, nothing had been lost. As to the Muslim population of the town, he further declared, all of them had emigrated from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and had been resettled in the villages around Edirne.Footnote 84 It seems that from the governor's point of view that the agony of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and its Muslim population was over. That page in the history of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa could be turned.

It is pertinent to note that in his survey of solutions offered to the refugees who had to leave the town permanently, the governor referred only to the Muslim refugees. Once they were all resettled in new homes, the need to find solutions was over. The Jewish refugees from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa were still lingering in makeshift shelters in Edirne. Finding solutions for their suffering apparently lay beyond the Ottoman governor's concerns. This omission, I would like to argue, reflected the tendency of the CUP government and its officials to highlight the Muslim character of the Ottoman state—one of the major outcomes of their defeat in the Balkan Wars.Footnote 85

Consequent to the peace agreement, the final Bulgarian takeover of the town made Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa a Bulgarian town, in both geopolitical and demographic terms. It lost its Muslim and Greek populations, and Bulgarian refugees joined the local Bulgarian community in reshaping the ethnic character of the town. It seems that one question remained blurred: the future of the small Jewish community and its exact place on the new map that shaped the Balkans.

The Unwanted: The Local Jewish Community

The case of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa can serve to explore another dimension of the tragedy that befell its civilian population—the fate of those who were deemed unwanted on the basis of their different ethnicity or religion. The small Jewish community of about five hundred members found itself squeezed between the two belligerent sides. Consequently, many of them found themselves trapped for weeks and months in the new border area and in makeshift accommodations in Edirne. Denied the ability to return to their previous homes in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa and forsaken by the two states that claimed sovereignty over the town, they had to negotiate their destiny by relying on their own individual efforts, the assistance and charity of the Jewish communities within the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria, and the help of transnational Jewish organizations.

As the Jewish community of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa is rarely mentioned in the academic literature, we must turn once more to the Ottoman salname to retrieve some information about it. Compared to the local Bulgarian and Greek communities, the size of the Jewish community was modest. The community was represented by a council (musevi cemaat meclisi), headed in 1901 by Yehuda Avram Efendi with two other council members belonging to the Razon family. Yehuda Efendi also served as a member of the subdistrict's education council, which conferred upon him the right to be addressed as an Ottoman official with the title of efendi. Together with Avram Ağa “the Tall”, who served in the municipality, they were the only Jews who played a role in the local administration. The community had its own school, which was affiliated with the French Jewish Alliance Israélite Universelle (established in Paris in 1860 and active in many parts of the Ottoman Empire), although it remained an independent institution.Footnote 86 There was one synagogue in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa.Footnote 87

The outbreak of the First Balkan War brought turmoil to the local Jewish community, as most local Jews fled from their homes in anticipation of an imminent Bulgarian conquest. Unlike many other small Jewish communities living prior to the war in Eastern Thrace who fled to Istanbul, the Jews of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa looked for temporary shelter in neighboring Edirne, only to find themselves trapped, as were the city's other inhabitants, in a protracted siege. Why did the Jews of Eastern Thrace choose to leave their homes hastily? An explanation may be found in a book written by Erol Haker, né Adato, who was born in 1930 in Istanbul to a Jewish family originating from Kırk Kilise (now Kırklareli), in the Edirne Province. His late father vividly remembered, even in old age, the confusion and agitation that engulfed his family and the family's hurried decision to leave everything behind and to flee, in the pouring rain, hoping to reach Istanbul. The family's memories from the previous Russian and Bulgarian conquest of the town during the war of 1878 left them with no illusions regarding their future under Bulgarian occupation. Therefore, they decided to leave their town in search of temporary shelter in Istanbul.Footnote 88

A report published in a Jewish journal in Sofia in May 1913, after Edirne's capitulation, referred to the plight of the Jews who had fled from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa during the First Balkan War. All 130 Jewish families of the town, it reported, fled their homes; most of them to Edirne and some to various cities in “old Bulgaria,” the term used by the Bulgarian press when referring to Bulgaria's borders prior to the Balkan Wars.Footnote 89 In a similar manner, the American Jewish Yearbook, dedicated to major events that took place in the Jewish world during the year 5674 (October 1913 to September 1914), mentioned the events in the Balkans during the war. A summary of the events noted that the town of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa was occupied by the Bulgarian army already on October 18, 1912. It claimed that most of the Jewish homes were destroyed during the battle for the town. Following this, more than one-half of the Jewish population fled to Edirne.Footnote 90

The capitulation of the Ottoman garrison in Edirne and the establishment of Bulgarian rule over the city during the final stages of the First Balkan War seemed to enable the Jewish refugees to return to their homes in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. Indeed, in early May, Rabbi Haim Bejerano, the Chief Rabbi of Edirne, declared that the “miserable sons of Mustafa Pasha,” who had lost everything, had commenced returning to their town.Footnote 91 Toward the end of April 1913, La Luz reported that the repatriation of the Jews to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa had begun in small groups under the direction of the Jewish-Bulgarian Association of Aid that opened a branch in Edirne, now under Bulgarian rule. Already at that time twenty-five families had been installed in their own homes or in rented facilities. The journal likewise reported that thanks to ownership documents, they could reclaim their property without facing any objection, either from the local authorities or their neighbors, and that no one harassed them. The journal further declared happily that the military authorities had adopted strong measures against anti-Jewish demonstrations on the part of some local Bulgarians and especially against the fires that had been set in some Jewish homes. Even more to the point, General Vladimir Vezov, the governor of Macedonia, issued a notification to the population of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa to stay away from any agitation or disorder against the Jews, threatening that any maltreatment of the Jews would be severely punished. The journal hoped that such a strong reaction by the civilian and military authorities would enable the Jews to return peacefully to their homes.Footnote 92

However, this was not the case, as local Bulgarians were determined to prevent such a return. Reading between the lines of the above report, we can assume that rights over abandoned property probably were the main motive of those Bulgarians who resisted the Jews’ return. Indeed, the American Yearbook claimed that the series of fires in May as well as the hostility of the population, insufficiently checked by the Bulgarian authorities, had added to the hardships of the wars.Footnote 93 La Luz provided more details. It reported that the Jewish population of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa had decided to return to their town and therefore they had approached the military commander in Edirne who, indeed, had authorized their return. However, when several families were about to leave Edirne, they were ordered to stay put, as it was reported that the community's communal assets had been set ablaze. Apparently, arson had been committed by some locals determined to prevent the Jewish families from returning to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa. Therefore, their repatriation became more complex, and they had to remain in Edirne.Footnote 94 According to another report, several conflagrations took place in the town, destroying the synagogue and several houses that had been occupied by Jews. The Bulgarian authorities held an inquiry; the existence of a criminal gang was asserted, by whom the outrages had been perpetrated, but the authorities were unable to discover the identities of the guilty persons.Footnote 95

Attempting to find a solution, the dispossessed Jews of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa turned to the community of Sofia for help. For centuries, smaller Jewish communities had appealed to the larger communities in the Ottoman Empire for assistance and guidance when in need. Adjusting themselves to the new political circumstances, they hoped that the Sofia community would be able to assist them as the Edirne community had previously done. Indeed, as Bulgarian sovereignty over much of Eastern Thrace seemed to stabilize, the plight of the Jews of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa gradually shifted from the pages of the Ladino press in Istanbul toward the Jewish press in Sofia. Toward the end of June, a delegation representing the Jewish refugees from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa who were still lingering in Edirne arrived in Sofia. They pleaded “with tears in their eyes” that these refugees be relocated to different cities in “old Bulgaria.” The refugees’ situation was desperate, reported the journal, and they could not remain in such conditions anymore in Edirne, where there was no work for them nor any possible assistance.Footnote 96 Before his departure for Western Europe, Dr. Ehrenpreis, Chief Rabbi of Bulgaria, had an interview with Ivan Geshov, the prime minister, who promised to do his utmost to prevent the recurrence of what he defined as “the regrettable incidents” and to facilitate the repatriation of all Jewish refugees.Footnote 97

The deteriorating situation of the Jewish refugees attracted the attention of leading Jewish newspapers of the diaspora. The Jewish Chronicle of London reported through its correspondent in Istanbul that the entire Jewish population of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, numbering about 530, had fled the town, most of them taking refuge in Edirne, while others were scattered in the interior of Bulgaria. Until the end of May, the Jewish community of Edirne had taken care of their needs by means of subsidies allocated for this purpose from the Jewish Relief Committee in Istanbul. The families who took refuge in Bulgaria attempted to return to the town, but they met with considerable hostility from “certain elements of the population.” Thanks to the intervention of the chief rabbi of Bulgaria with the government, some “very severe measures” were taken enabling them to return. Yet upon their arrival, they found that their homes and shops had been looted and that they could not make a fresh start.Footnote 98

Bereft of any state assistance and due to the temporary return of Ottoman rule, in July 1913 the Jews of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa looked again for help from the Jewish community in Istanbul. They sent an “Appeal for Help” signed by the Jewish community of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa to El Tiempo, which was published in September 1913. The poignant appeal was written in biblical Hebrew, invoking the language of grief of previous generations and traditional elegies. It begged for assistance for the Jewish community “that stands on the border separating Bulgaria and Turkey, overwhelmed in the agony of poverty and hardship. [This misery] is a consequence of the Balkan War—the cause of all the terrible devastations and awful abominations and the source of all the terrifying and aggravating misfortunes to which we were subject.” The applicants bemoaned their situation, as they remained totally ruined and without means to sustain themselves.Footnote 99

In late September, with the town again under Ottoman rule, the Jewish Chronicle declared, “The small Jewish community [of] Mustapha Pasha is truly worthy of pity.” It summarized the effects of the Bulgarian evacuation of the town during the Second Balkan War and the reinstitution of Ottoman rule. According to the journal's reporter in Istanbul, the Bulgarians turned the synagogue and Jewish school into stables, and upon their departure from the town destroyed both altogether. Following the reconquest of the town by the Turks, some Jewish families from the town appealed for help from the communities of Edirne, Rodoso (today Tekirdağ), and other communities in Thrace, but those communities all found themselves in a similar plight and were unable to help. The journal ominously predicted, “unless help is promptly forthcoming, the Jewish inhabitants of Mustafa Pasha say that they will be obliged to go into exile.”Footnote 100

It appears that the final setback befell the Jewish refugees from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa only after the situation had stabilized with the return of Bulgarian rule. Although both Muslim and Bulgarian refugees were resettled by their respective state authorities, the Jews apparently remained for a while in limbo. The leadership of the Jewish community in Edirne provided some statistics. In early October 1913, it was reported that as Bulgaria regained control over the town, those Jewish families who had resettled in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa during the brief Ottoman rule over the town chose to emigrate once more to Edirne. The Jews of Edirne somehow managed to absorb them in buildings belonging to the community. About ninety families settled in Edirne, and about a dozen preferred to move to Istanbul. The Edirne community complained about the burden of assisting all of those “poor despondent individuals, such as widows and orphans and to take care of the education of their children.”Footnote 101 A report published in La Boz de la Verdad in Edirne in March 1914 provides some details regarding the refugees’ situation in Edirne after the conclusion of peace between the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria:

More than sixty families, among them 15–20 widows, are temporarily sojourning in Edirne. Apart from several of them who can somehow live in miserable conditions, the others are literally dying of hunger. Some of them still have some property in Mustafa Paşa and want to make use of it; however, they cannot do so as they do not have the resources necessary to go to their city and apply to the Bulgarian authorities. Some of them wish to reclaim at least their landed properties but are not able to do so because they do not have the required resources to travel to Mustafa Paşa and to seek their rights before the Bulgarian authorities. They have to choose between staying in Edirne and returning to their place of origin. However, both options are difficult, as if they choose to stay in Edirne, they cannot support their families; if they choose to return empty-handed to Mustafa Paşa—they will not be able to sustain themselves. We were informed that the Bulgarians began to construct barracks that could serve as houses and shops. Our brothers can only watch these constructions from afar and cannot use their own properties to gain bread for their children.

The reporter claimed that only Bulgaria could put an end to this despair by reconstructing the community in its place and returning the Jews’ properties to their rightful owners.Footnote 102

It seems that the pressure on the Jewish refugees from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa continued to increase, as the local Ottoman officials’ tolerance of their presence diminished and they began to initiate steps to expel them. In early July 1914, the Ottoman Department of General Communication at the Ministry of Internal Affairs sent a telegram to the vilâyet of Edirne requiring them to check claims that Jews who settled in nearby Uzun Köprü were being threatened and forced (tazyik ve icbar) to relocate (nakl-ı hane) to Yeni Mustafa Paşa.Footnote 103 Was the governor's order part of an attempt to find a permanent solution for the Jewish refugees from Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa? Even if this were the case, apparently the Jews perceived this administrative step as an attempt to deport them from their place of refuge. The phrasing of the Ottoman correspondence mentioned above seems to support this perception of the Jews.

A report in a Jewish journal provided more details. It disclosed that the governor (kaymakam) of Uzun Köprü had to leave the town under an order received from his superiors. It was noted that the kaymakam had ordered those Jews of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa who settled in Uzun Köprü to leave, giving them twenty-four hours to depart from the town and move back to Yeni Mustafa Paşa. Following an appeal by the representatives of the Jewish community, the governor opened an investigation and informed them that this decision came from the ministry. It is clear from the Jewish journal report that the central government authorities intended to uphold their obligation to prevent injustices by petty officials; they apparently deemed the banishing of Jews from their temporary refuge in Uzun Köprü to be an insubordinate and antipatriotic measure.Footnote 104 The final reference to the Jews of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa was dated June 1914. A report published in La Luz in Sofia referred to the request of Bulgarian Jewish leaders who pleaded in Sofia for those refugees from the remaining “new Bulgarian provinces,” most probably referring to Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa, to be relocated to different communities in “old Bulgaria,” as no assistance could be secured for them in Edirne.Footnote 105 There is no reference to a Jewish community in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa/Svilengrad after this date. Probably most of the refugees were able to find permanent accommodation in Bulgaria or among other Jewish communities of the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 106 For them, personal connections and family affiliations rather than the state offered solutions.

The plight of the Jewish community of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa suggests a grey area in which identity and citizenship became blurred and great latitude was left for local actors, whether by marginalizing the former Jewish inhabitants or by offering them assistance. What stands out in this case is the local Jews’ inability to find their proper place after the Balkan Wars. Deemed unwanted by both local Bulgarians and Ottomans, they found themselves in limbo, abandoned to their suffering. Their case also demonstrates the ability of local Bulgarians to enforce their will to deny the Jews’ return. Different testimonies make it clear that the Bulgarian political and military leadership accepted the right of local Jews to remain in their town. This should not surprise us, because the first constitution adopted by the Principality of Bulgaria in 1879 as well as subsequent citizenship legislation (until 1940) had already acknowledged the right of all those living on Bulgarian territory to benefit from Bulgarian citizenship without distinctions relating to religion or ethnicity. The principle of jus soli bestowed equal citizenship on Jews, Greeks, Muslims, and other nonethnic Bulgarians living in Bulgaria.Footnote 107

Nevertheless, local actors decided differently. Sometimes defined merely as “gangs,” these local actors were nevertheless able to take advantage of the Jews’ temporary exodus from the town to loot their properties and set fire to their houses and communal institutions. These arson attacks led to the demise of the Jewish community in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa/Svilengrad. The hesitant attempts of individuals to return and claim their property was quickly curtailed. Focusing on the significance of this story from the Ottoman authorities’ perspective, the displaced Jews of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa were not regarded as fellow citizens entitled to the state's assistance and compassion. Unlike Muslim refugees fleeing the lost provinces in the Balkans, the Jews of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa were left to fend for themselves. Sometimes their presence was not accepted, and local officials initiated their expulsion. On other occasions, their presence was tolerated, but no state assistance was offered to them. To survive in their places of refuge, they had to rely on the charity of local and transnational Jewish associations and networks.

Conclusions

The case of the small town of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa depicts the formation of an “ethnic cleansing area,” in which old patterns of cohabitation collapsed under the turmoil and the stresses of nationalist exclusion and war, and were transformed into a sensitive border situation in which harassment, displacement, and exclusion became the norm. The general context comprises the rise of nationalist ideologies, the impact of war, and the shift from a multiethnic and multireligious empire to a nation–state. Against the devastating outcomes of the Balkan Wars, the case of Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa stands out not only because of the terrible suffering of its civilian population; many other Ottoman towns and villages endured similar atrocities. Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa is unique due to the consequences of three regime changes, each one of them targeting different sections of the civilian population. Additionally, as it changed rulers and populations, it always remained near the military front or adjacent to the borderline, be it the Bulgarian or the Ottoman. The geopolitical position combined with shifting borders likely exacerbated feelings of uncertainty, suspicion, and menace. The perennial proximity of a threatened border probably strengthened feelings of both belonging and exclusion among the different local populations.

The unfolding of events and the identity of the perpetrators and helpers in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa/Svilengrad suggest that state agents, irregulars, and former neighbors all took part in the destruction of property and lives and in forcing those deemed unwanted out of their town. Although there are contradicting claims and testimonies about the identity of those who committed the arson attacks that devastated much of the town, first Bulgarians and later Ottomans targeted civilians in Cisr-i Mustafa Paşa/Svilengrad during and after the two Balkan Wars. Juxtaposing the Bulgarian and Ottoman narratives demonstrates how each group was straightforward in exposing the other's crimes, but silent when it came to its own side.