1 Introduction

Intermediaries were first introduced by the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 (YJCEA) to facilitate communication between individuals with communication needs and the criminal justice system. As one of a range of special measures contained within the legislation, the role has effected a ‘culture change’ (Cooper and Norton, Reference Cooper and Norton2017, p. 364) in the treatment of vulnerable witnesses. The function of the intermediary is to communicate to the witness questions put to the witness, and to communicate the answers to the person asking the questions. The assistance provided by an intermediary is often the difference between a witness being able to give evidence or not (MoJ, 2020, p. 5). Intermediaries come from a diverse occupational background including speech and language therapy, occupational therapy, psychology, social work, teaching and nursing, and bring the skills and experience gained in these roles to their work as intermediaries (Plotnikoff and Woolfson, Reference Plotnikoff and Woolfson2015).

The nature of intermediary work involves interaction with numerous actors – many of whom fill established roles, including the police, lawyers and the judiciary. Despite the differences between these actors, in terms of responsibilities and status, they share one commonality: all are traditionally considered to be ‘professionals’. Definitions of what constitutes a professional vary widely but have tended to centre on traits such as high levels of skill, a recognised body of knowledge and existence of an organising body (Ackroyd, Reference Ackroyd and Dent2016, p. 15). Scholars have tended to view the professionalisation of the criminal justice system as an incremental process with various roles identified by government as requiring greater accountability, modernisation and improved efficiency (Brough, Brown and Biggs, Reference Brough2016, pp. 66–67). Individual criminal justice roles have taken steps towards professionalisation at different points and also to different degrees (Brough, Brown and Biggs, Reference Brough2016). For example, the push towards professionalisation of the police has been well documented (Mark, Reference Mark1977; Green and Gates, Reference Green and Gates2014) and lawyers are frequently depicted as one of the ‘traditional’ professions (Brooks, Reference Brooks1998, p. 149). Indeed, the ‘court workgroup’ articulated by Eisenstein and Jacob (Reference Eisenstein and Jacob1977) is a theoretical construct made up exclusively of legal professionals, namely lawyers and judges.

This article examines intermediary work in context and focuses on how the work relationships that intermediaries develop impact its role and status. It presents the findings of an empirical, socio-legal enquiry based on thirty-one interviews with practising intermediaries in England and Wales and Northern Ireland as well as members of the judiciary of Northern Ireland. While research into intermediaries is increasing, the question of the role’s professional status has been either neglected or else simply taken for granted. This article examines the work tasks of intermediaries and how control over their work is established and maintained. The substantive discussion focuses on two main theoretical constructs. The first is Abbott’s (1988) work on interprofessional jurisdictional disputes which details how professions operate in dynamic social settings which shape and define individual professional roles. Jurisdictional conflicts characterise social processes, but how these jurisdictional boundaries are created, maintained and shift can be examined using Gieryn’s (Reference Gieryn1983) conception of boundary work. Boundary work outlines how professionals demarcate the boundaries which represent status, autonomy and claims over professional resources. The article concludes by reflecting on the various conflicts which the intermediary faces in trying to secure and maintain jurisdiction. It asks if the role’s jurisdictional conflicts will result in a ‘jurisdictional settlement’ whereby intermediaries accept a more limited role with distribution of some of their work tasks among other criminal justice actors (Abbott Reference Abbott1986, 1988).

2 Background

In England and Wales, the intermediary was created by Section 29 of the YJCEA and first implemented by the Witness Intermediary Scheme (WIS) in 2004 through a pilot study. The WIS was eventually implemented nationally in 2008 and matches vulnerable witnesses with an intermediary based on their communication needs. These intermediaries are trained, registered and regulated by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and are known as ‘Registered Intermediaries’. Defendants, however, are excluded from the YCJEA’s special measures regime. As a result, any application for intermediary assistance for a vulnerable defendant must be dealt with under common law, applying the court’s inherent powers to ensure a fair trial. Although Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunal Service (HMCTS) launched the ‘Court Appointed Intermediary Service’ (HAIS) in April 2022, which includes intermediary provision for defendants, there is still no statutory basis for such appointments.Footnote 1 In other words, a two-tier intermediary provision has emerged (Henderson, Reference Henderson2015). Defendant intermediary appointments are decided on a case-by-case basis, but there exists a presumption against the use of an intermediary for a defendant at trial (Criminal Practice Directions (CPD), 2015, 3F.12). Registered Intermediaries in England and Wales routinely attend police stations, as well as other locations such as schools or homes, to assess vulnerable witnesses. They also work with police to plan interviews and can facilitate communication during interviews. Defendant intermediaries rarely assist suspects at the police station, though when they do, it is on an ad hoc basis. At court, Registered Intermediaries facilitate communication during oral testimony. While an intermediary may be appointed to assist a defendant throughout the duration of a trial, the Criminal Practice Directions (2015, para. 3F.14) note that this should be ‘extremely rare’. Most intermediaries on the MoJ register are speech and language therapists, however, there has been an increase in numbers from other backgrounds, such as teaching, nursing, social work, psychology and occupational therapy (Email correspondence from Ministry of Justice to author, 2021).

In 2013, the Department of Justice of Northern Ireland (DoJ) developed a model for the provision of intermediaries for vulnerable complainants and witnesses in the criminal justice system. This was based on the provisions of the Criminal Evidence (NI) Order 1999 (Arts 17 and 21BA), which mirror the provisions of Section 29 of the YJCEA. The function of these specialists would be to ‘facilitate communication during the police investigation and at trial between a person with significant communication deficits and others in the criminal justice process’ (DoJ, 2015, p. 5). Intermediaries in Northern Ireland are trained, registered, and regulated by the DoJ. As in England and Wales, the majority of those on the Registered Intermediary Scheme (RIS) register are speech and language therapists, with a number hailing from a social work background (Email correspondence from DoJ to author, 21 August 2020). The DoJ concluded that respect for the principle of equality of arms demanded that all vulnerable individuals – including defendants – should be eligible for intermediary assistance (DoJ, 2015). The RIS was subsequently established to allow end users – in other words, police, prosecutors and defence solicitors – to access intermediary services. Intermediaries can assist both witnesses and suspects at the police station, assist with the planning of interviews, and attend interviews to facilitate communication (DOJ, 2015, p. 3). Intermediaries in Northern Ireland are appointed on an ‘evidence-only’ basis; in other words, they are appointed to assist during the period of testimony only (LCJ Crown Court Practice Direction, 2019, A5.4).

In both jurisdictions, intermediaries are involved in pre-trial case management hearings known as ‘Ground Rules Hearings’ (GRH). The GRH affords the intermediary the opportunity to discuss with the advocates and the judge any adjustments to questioning and any other recommendations contained within the Court Report. The GRH should establish the rules relating to the manner and duration of questioning, how the intermediary may intervene if necessary and generally how the intermediary will assist the advocates and judge (MoJ, 2020, p. 22; DoJ, 2019, pp. 45–46). The judge may also order that the intermediary reviews the questions that the advocates plan to ask the witness and provide advice on their suitability in terms of the witness’s communication needs. The judge makes the necessary directions to set the parameters for fair treatment of the witness (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper2015, p. 431).

3 Methods

This article presents findings from thirty-one in-depth, semi-structured interviews with intermediaries and judges. All intermediaries had experience of working with both (i) witnesses and complainants and (ii) suspects/defendants. It was important that all interviewees could speak to their experiences of working with both categories of vulnerable individual. Of the twenty-seven intermediaries interviewed, twenty were based in England and Wales and seven in Northern Ireland.

Interviewees responded to a request sent on my behalf by ‘Intermediaries for Justice’, a registered charity promoting and supporting the work of intermediaries. Further requests were sent via the ‘Registered Intermediaries Online’ portal which is operated by the National Crime Agency (NCA). In Northern Ireland, interviews were arranged in collaboration with the Intermediaries Schemes Secretariat (ISS) who disseminated information to all Registered Intermediaries on my behalf. In Northern Ireland, four judges were interviewed (two District Judges who sit in the magistrates’ court and two Crown Court judges) through the Lord Chief Justice’s Office. These judges were selected based on their experiences of working with intermediaries in the criminal justice system.

In terms of the representativeness of the sample, over one third of the total intermediary cohort in Northern Ireland was interviewed (DoJ, 2016). When interviews commenced in November 2018, there were 115 intermediaries on the MoJ register actively taking cases (email correspondence from Intermediaries for Justice to author, 26 April 2018). Based on anecdotal evidence from the field, it is estimated that less than half of those intermediaries would be in a position to comment on working with witnesses and defendants. Therefore, one can say with reasonable confidence that the twenty interviews conducted amounted to a significant percentage of the target population. Of the twenty-seven intermediaries interviewed, fifteen came from a speech and language therapy background, three from social work, three from nursing, two from occupational therapy, two from psychology, one from teaching and one worked with deaf people as a Sign Language interpreter.

All interviewees were provided with an information sheet prior to interview and signed a consent form agreeing to their participation. I anonymised each interviewee and have used the prefix ‘NI-’ to identify interviewees in Northern Ireland and ‘E&W-’ for those based in England and Wales. I used ‘CCJ-’ to denote Crown Court judges and ‘MCJ-’ to denote judges in the magistrates’ court. Ethical approval was obtained from the London School of Economics.

4 The question of ‘professional’ status

The professional status of the intermediary, and what that label may entail, is not clear. The terms ‘professional’ and ‘professionalism’ are used by both the DoJ (2015) and MoJ (2020) when describing the organisation of intermediaries and the standards expected of their work. Further, the penultimate chapter of Plotnikoff and Woolfson’s (Reference Plotnikoff and Woolfson2015, p. 281) seminal book on intermediaries is entitled ‘A new profession’ with the opening line noting that intermediaries ‘have emerged as a new professional identity’. Many, therefore, seem to take for granted that the intermediary is a professional role. A rich literature on the ‘sociology of the professions’ analyses professions as modes of social organisation and as the locus for other social processes and dynamics, allowing scope for an enquiry into the professional status of the intermediary. Nonetheless, while an understanding of professional identity is a key component of this body of work, this article focuses on mapping what intermediaries do rather than how they are categorised. In fact, seeking to define a ‘profession’ and analysing the intermediary against the resulting definition is potentially ‘unnecessary and dangerous’ (Abbott 1988, p. 58), since it distracts from the content of the role’s work and how intermediaries think about, act towards, and ultimately justify their work. As a result, it is accepted that the intermediary can be viewed as a professional without enquiring too deeply into what that means.

Relevant to the professional status of the intermediary is the variety of occupational backgrounds from which practitioners come (the varied occupational backgrounds of the intermediaries I interviewed are reflected in Table 1 below). Many of the intermediaries whom I interviewed spoke about their previous professional roles and the experience of bringing their existing skill set to a new work environment. How these diverse backgrounds may shape, or even hinder, the emergence of a new professional status is complicated by the fact that many carry out their role as an intermediary ‘on the side’, in addition to their main professional role. Indeed, several intermediaries spoke passionately about the importance of being recognised as professionals:

‘[Judges] have started to expect a psychologist or psychiatrist to recommend us. That’s another problem we have, they are wasting money on a psychological report because they want a “professional” to decide whether we’re needed or not. They’re not recognising us as professionals.’ [E&W-17] [emphasis added]

Table 1. Occupational background of intermediary interviewees

It does not seem that this view is widely held amongst judges, however. For instance, one magistrate I interviewed indicated that the intermediary’s status as a professional had been all but secured:

‘Now, everybody is clear they are professional experts who are providing an independent role within the trial.’ [MCJ-2]

While this article does not seek to question the intermediary’s status as a professional, it is concerned with whether intermediaries are engaged in what Abbott (1988) calls ‘professional work’. It is the conduct of this work which determines the parameters of inter-professional jurisdiction between the intermediary and the police, lawyers, judges and others (Abbott, 1988, p. 58). By drawing on the concepts of ‘jurisdiction’ and ‘boundary work’ we can examine the content and context of intermediary work, the expertise which underpins it and the interdependent nature of the network of actors in the criminal justice system. Could such an inquiry be a precursor to a full examination of the intermediary’s professional status? Quite possibly, yes. But merely labelling the intermediary a professional tells us little about how its practitioners are involved in a process of negotiation, conflict, and exchange with other criminal justice actors. As such, this article examines intermediary work within a dynamic social context rather than treating any intermediary ‘profession’ as a static entity or a fixed social structure (Suddaby and Muzio, Reference Suddaby, Muzio and Empson2015, p. 30).

The next section introduces the concepts of ‘jurisdictions’ and ‘boundaries’ as theorised by Abbott and Gieryn respectively.

5 Jurisdictions and boundaries

5.1 Jurisdictions

Abbott views professions as operating in a complex system of interdependence and he evaluates the link – which he terms ‘jurisdiction’ – between occupations and their work. The notion of jurisdiction relates to the control occupations assert over certain task areas. In the case of the intermediary, this concerns how practitioners assert control over tasks, such as assessment, interview planning, and formulation of recommendations in the court report. Later in the article, we will see how this control is effected through the components of ‘diagnosis’, ‘inference’ and ‘treatment’. The importance of the control or ‘jurisdiction’ claimed over work tasks is hard to overstate. If, when and how intermediaries may be said to carry out ‘professional work’ is defined by the jurisdiction they assert over this work (Abbott, 1988, pp. 2–9).

The focus on jurisdiction is conceptually useful as intermediaries operate in dynamic social settings in the criminal justice system with potential overlap between respective work tasks. For example, Jackson (Reference Jackson2004) highlights the expanding role of prosecutors into pre-trial investigatory functions and notes more generally how ‘quasi’ roles can emerge when jurisdictions overlap. With specific reference to the criminal court, Young (Reference Young2013) explains that jurisdictional boundaries of the court workgroup are closely guarded by its members as threats to its work tasks emerge. As a result, we may ask: Are the work tasks of the intermediary susceptible to encroachment and does the intermediary similarly engage in encroachment when staking claims to jurisdiction? This question is key to understanding the nature of the intermediary’s work and whether the role enjoys ‘jurisdiction’ or ‘control’ over it. Abbott’s systems model acts as a cogent framework for examination of how respective jurisdictions are both expanded and defended. Asserting that these jurisdictional boundaries are perpetually disputed, Abbott (1988) argues that this conflict occurs because professions are in constant competition for control over work tasks.

Two main reasons underpin the decision to focus on Abbott’s systems model. Firstly, it is concerned primarily with the content of the work carried out by occupational groups. This aspect of Abbott’s (1988, p. 187) model resonates with the rich data I gathered about the intermediary role and the ‘common work’ of its practitioners. Abbott’s theory is also relational at its core. My interview data tells a story of a new actor in the hierarchical, ritualistic criminal justice system and explores how resulting conflicts with other actors are constitutive of the role. Secondly, Abbott (1988, p. 317) explains that his model extends beyond analysis of the professions and ‘offers a way of thinking about divisions of labour in general’. This allows for an examination of intermediary work without the need to explore the role’s professional status. Abbott ignores addressing the issue of when groups can be said to have coalesced into professions and instead focuses on why new groups arise and how they disturb the system. (Tolbert, Reference Tolbert1990). The systems model therefore allows a focus on ‘the contents of professional activity [and] the larger situation in which that activity occurs’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 2).

5.2 Boundary work

If Abbott’s concept of jurisdictions explicates conflicts over interprofessional domains, then ‘boundary work’ is the activity performed in constructing and negotiating the boundaries that mediate interaction. Changes between professional work tasks (for example, prosecutors assuming some investigatory functions as explained above) tend to occur most often at the ‘edge of professional jurisdictions’ (Abbott, 1995, p. 857). Examining these boundaries, their edges and how they are crossed, aids understanding of inter-professional jurisdiction and how it is secured and maintained. Gieryn (Reference Gieryn1983, p. 781) explains how the concept of boundary work is widely applicable as boundary demarcation ‘is routinely accomplished in practical, everyday settings’. It has proven particularly useful when researching emerging groups seeking to ‘communicate their subject [and] establish their own credibility to talk authoritatively about their subject’ (Riesch, Reference Riesch2010, p. 454). This description fits well with the position of intermediaries as an occupational group. Building on this, we can examine how the intermediary uses boundary work as ‘strategic practical action’ to monopolise professional authority and expertise (Gieryn, Reference Gieryn1983, p. 23).

Both concepts of jurisdiction and boundary work are complimented by ‘knowledge claims’: claims through which professionals control knowledge and skill which act as ‘important currencies of competition’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 102). Knowledge claims play a key role in achieving jurisdictional control and ‘represent an important vehicle through which professions can rhetorically play out their professional struggles’ (Hirschkorn, Reference Hirschkorn2006). Such knowledge claims, and how they are demonstrated, thread throughout the three components of professional work discussed below (diagnosis, inference and treatment). How intermediaries perform boundary work and how they assert knowledge claims is key to securing what Abbott terms ‘exclusive jurisdiction’ over their work. This sees occupational groups aspire to achieve full control over work tasks which they justify based on expertise and exclusive knowledge (Abbott, 1988, p. 192). Why is this concept of exclusive jurisdiction important? Firstly, the use of the word exclusive suggests legitimacy – i.e. that the intermediary has been able to achieve control of its tasks through successfully persuading other actors of its expertise (Abbott, 1988, p. 188). Further, since jurisdiction is exclusive, movement in the jurisdiction of one profession invariably affects those of others. Therefore, by securing exclusive jurisdiction over its work tasks, the intermediary causes disturbances in inter-professional jurisdictional relations. This ‘chain of effects’ is particularly important to understanding the nature of the jurisdictional settlement that the intermediary achieves with other criminal justice actors which is addressed later in the article. (Abbott, 1988, p. 192).

The next section considers how the existing boundaries of the criminal justice system have been disturbed by the introduction of the intermediary and how the network of actors has responded accordingly. This section focuses on the introduction of the intermediary into a new work setting causing disruption, upheaval and uncertainty. In the words of Abbott, jurisdictional boundaries are perpetually in dispute and the system must ‘absorb’ the disturbance(s) in seeking to regain balance (Abbott, 1988, p. 215).

5.3 Boundary disturbance

What impact has the introduction of the intermediary had on the pre-existing social structures of the criminal justice system? Abbott (1988, p. 33) contends that when a new actor enters such a field there is inevitably ‘jostling and readjustment’. Indeed, when a new actor such as the intermediary appears ‘requiring professional judgement or a new technique for old professional work’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 89), then the system must necessarily react. The conflict amongst competing jurisdictional claims requires a closer examination of boundary disturbance. The existence of boundaries in the criminal justice system helps regulate inter-professional relationships as well as allowing individuals to perform their roles within ‘procedurally correct boundaries’ (Bergman Blix and Wettergren, Reference Bergman Blix and Wettergren2018, p. 86). It is a complex social world where both physical and non-physical boundaries dictate who sits where, who speaks to whom, and how much involvement in proceedings individuals will have (Liu, Reference Liu2018, p. 47). But when changes are introduced which upset cultural norms, resistance from established criminal justice actors normally follows. Young (Reference Young2013, p. 218) describes how established actors ‘patrol and defend’ established boundaries. This mirrors Abbott’s notion of competitive struggles for jurisdiction and we can examine how the intermediary as an outsider acts to disrupt existing jurisdictional arrangements. These themes are germane to how intermediaries construct and maintain boundaries to demarcate their own ‘independent … self-contained area of knowledge’ and how they seek recognition in claiming jurisdiction over it (Fournier, Reference Fournier and Malin2000, p. 67).

As sites of contestation, boundaries demarcate distinctive bodies of knowledge and expertise (Liu, Reference Liu2018, p. 49). The stability of professional role boundaries within the criminal justice system (and particularly within the court) has been well rehearsed. Eisenstein and Jacob (Reference Eisenstein and Jacob1977, p. 10) describe the ‘common task environment’ of the ‘courtroom workgroup’ where specialised functions are orientated towards shared goals. Boundaries are collectively drawn which ensures that ‘everyone quickly fits into his accustomed place … Even novices readily fit into the work routine of a courtroom’ (Eisenstein and Jacob, Reference Eisenstein and Jacob1977, pp. 29–30). The pre-court environment, and in particular the evidence gathering procedures, is also carved up primarily between the police and prosecution in a way that McConville et al. (1991) argue amounts to the collaborative venture of ‘case construction’. Similarly, Sanders (Reference Sanders2002, p. 14) highlighted how the prosecution prepare cases ‘hand in glove’ with the police where boundaries inevitably overlap and intertwine. The boundaries demarcating the work of individual actors give rise to jurisdictional claims which, at least according to the workgroup, are mutually recognised in pursuance of collective goals.

For intermediaries to construct boundaries they must stake jurisdictional claims. Abbott (1988, p. 60) defines this as a claim for ‘the legitimate control of a particular type of work’ which entails ‘first and foremost a right to perform the work as professionals see fit’. However, several intermediaries discussed being unsure about where the role seemed to fit among the established practices and routines of the criminal justice system. Equally, the lack of understanding of the intermediary role and its function from other criminal justice actors has been a theme in the research carried out to date (Victims’ Commissioner, 2018; Plotnikoff and Woolfson, Reference Plotnikoff and Woolfson2011). It became clear in my interviews that this made identification and performance of intermediary work difficult:

‘It was awkward because the barristers I worked with didn’t have any idea what my role is. I was not totally convinced by my role, and similarly with police, you were requested but that officer might not think they need you.’ [E&W-6]

‘It was almost like I have landed in this box and nobody has a clue what to do. It was like someone had dropped me in … There was no lead from the prosecution or from the bench and I was standing there thinking: “how long will I be standing here …” and that was really bizarre … I came away thinking: “did they know what my role was and why I was there?”’ [E&W-20]

Interactions between legal practitioners and intermediaries in the early stages of both schemes in Northern Ireland and England and Wales reflected an even greater lack of understanding. Despite the RIS covering both witnesses and defendants from the outset in Northern Ireland, interviewees found that solicitors were sometimes completely unaware of what an intermediary was or what the role entailed:

‘I think there was a definite lack of awareness of what we do from solicitors. One solicitor didn’t know about RIS and asked me “What is it you do again?” He then said a few weeks later: “I definitely need a Registered Intermediary” so he made an application.’ [NI-6]

Defendant intermediaries in England and Wales found the boundaries of the role particularly difficult to gauge when dealing with solicitors. In the absence of any specific guidance on the point, many felt that solicitors struggled with how much information about the case the intermediary needs to know prior to an assessment. Initially, many defendant intermediaries were swamped with mountains of medical evidence with little idea of their relative ethical position or how much reliance they could place on the provided material:

‘I have had whole bundles arrive at the office for somebody in a trial in 3 weeks’ time and I have never met them, never said I can do it … And there is highly confidential information that just rocks up, so I think GDPR hasn’t reached the legal world … It’s unnecessary … some solicitors seem unable to distinguish or differentiate what I might need.’ [E&W-2]

These examples demonstrate how construction of boundaries posed a challenge as the content of the role had yet to be developed, shaped and tested through practice. As a ‘new player’ in the criminal justice world, the lack of precedent for the role provided scope for its parameters to be tested (Plotnikoff and Woolfson, Reference Plotnikoff and Woolfson2015, p. 3). Similar experiences have been found among interpreters, for example, who often encounter ‘attitudinal resistance’ (Hale, Reference Hale2011, p. 3) to their practices as well as challenges in managing expectations of their role (Colley and Guéry, Reference Colley and Guéry2015). The autonomous nature of Interpreting and lack of prior knowledge of the subject of their assignment also draws parallels with intermediary work (Colley and Guéry, Reference Colley and Guéry2015). At its heart, boundary construction is about distinguishing from other professionals, but intermediaries were initially constrained from doing so in an unfamiliar environment (Liu, Reference Liu2018). This contrasts sharply from the norms, attitudes and common understandings which accumulate and are inculcated in the courtroom workgroup over a long period of time (Young, Reference Young2013). But it was not just intermediaries who initially struggled with the parameters of the role’s professional boundaries. Other actors appeared unsure as to how the role may challenge their own jurisdictional domains. One Magistrate commented:

‘When it first came out, I can remember a complaint, or an issue being raised in the Crown Court where a Registered Intermediary had felt they had got a particularly hard time and there was clearly a lack of understanding of the role from everybody. Everybody had felt that when they looked at it there was a lack of understanding of the role.’ [MCJ-2]

E&W-6, E&W-20 and MCJ-2 were reflecting on the encroachment of a new actor into a system with well-defined work tasks and boundaries. As Rock (Reference Rock1993, p. 261) explains, there is an ‘abiding preoccupation with the conflict, danger and threat to confidentiality represented by outsiders’. As a member of the ‘courtroom workgroup’, MCJ-2’s remarks signal an appreciation of the ‘conflict, uncertainty, and inefficiency’ that the introduction of a new actor can engender (Young, Reference Young2013, p. 220). More generally, these comments point to concerns and anticipation as to how the introduction of the intermediary role may impact inter-jurisdictional competition over tasks. Timmermans terms this an instance of a ‘conflictual jurisdictional relationship’ when traditional actors are ‘confronted with the incursions of an emerging profession on its jurisdiction’ (Timmermans, Reference Timmermans2002, p. 570). Blok et al. (Reference Blok2019) offer a variant notion of the ‘proto-jurisdiction’ to explicate how professions navigate ‘emerging task arenas’ by renegotiating work routines among themselves.

As will be discussed further below, the ‘vacancy’ which was created for the intermediary through the YJCEA is contested by others who question the nature of the role’s jurisdictional claims. What must now be considered is how such claims emerge. Jurisdictional claims are staked only through the demonstration of an ‘independent and self-contained field of knowledge’ (Malin, Reference Malin1999, p. 69). This serves to legitimise the work and sustain the jurisdiction claimed (Abbott, 1988, pp. 52–57). Just as the judges and lawyers in Eisenstein and Jacob’s court workgroup identify specialist tasks to be executed, the intermediary role has sought to carve out control over certain tasks. An examination of how the intermediary claims or holds ‘jurisdiction’ over its tasks requires examination of the content of the role’s ‘professional work’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 59). The ‘problem’ which the intermediary was introduced to remedy, i.e. the criminal justice system’s failure to adequately accommodate the needs of the vulnerable, is shaped into coherent jurisdictions and resulting claims (Abbott, 1988, p. 35). These claims are underpinned by three acts of professional practice which frequently overlap and intermesh: diagnosis, inference and treatment (Abbott, 1988, p. 40). The next section will discuss each of these in turn.

6 Professional work

What is it that intermediaries ‘do’ as professionals and on what basis can they justify their control over it? We can refine this question by asking: how does intermediary work constitute a professional field of expertise which amounts to a legitimate area of knowledge? (Fournier, Reference Fournier and Malin2000, p. 69) Whether or not intermediaries operate autonomously in a field which is independent and self-contained is central to understanding how claims of jurisdiction can be made. The three ‘parts’ of professional tasks identified by Abbott are i) diagnosis, ii) inference and iii) treatment. Together, these embody the essential cultural logic of professional practice and constitute the tangible work in which professionals engage (Abbott, 1988, p. 40).

6.1 Diagnosis

Diagnosis is a ‘mediating act’ whereby information is taken into the professional knowledge system and assembled into a picture that can then be classified (Abbott, 1988, p. 40). For intermediaries, the act of diagnosis takes place at the assessment stage. The assessment has come to be described as what ‘underpins intermediary recommendations about adapting questioning techniques and procedures at the police station and at court’ (Plotnikoff and Woolfson, Reference Plotnikoff and Woolfson2015, p. 39). The first cohort of intermediaries selected and trained by the Home Office were shown how to compile a court report based on their individual assessment of the vulnerable person and their communication needs. However, a surprising discovery from my interviews was that Registered Intermediaries in both jurisdictions spoke of a complete lack of formal training from either the DoJ or MoJ on assessment techniques. The four official Registered Intermediary Surveys conducted by Cooper since 2009 detail the use of intermediaries in court, their interaction with lawyers, judges, and court staff, with almost no mention of what many intermediaries see as the focal point of their role. It seems that Registered Intermediary training initially focused more on preparing the intermediary for entrance into the legal world than the practical reality of assessment techniques (Cooper, Reference Cooper2014).

The scope of the intermediary’s diagnostic role is recognised in the official procedural guidance manuals. The relevant MoJ guidance (2020) requires Registered Intermediaries to identify whether their involvement is likely to ‘improve the completeness, coherence and accuracy of the witness’s evidence’. The DoJ (2015) in Northern Ireland adopts an almost identical requirement. This phraseology allows for a mix of individuals from different backgrounds to perform the role without having to make a formal medical diagnosis. For many, this contrasts sharply with the requirements of their other professional positions where such a diagnostic role is crucial. As has been noted above, the eligibility criteria are different for a defendant intermediary than a Registered Intermediary. For defendants, an appointment can be made to ensure that ‘every reasonable step is taken to facilitate the defendant’s participation’ in proceedings (CPD, 2015, para. 3F.21). In addition, the assessment practices of non-registered intermediaries have been free from official scrutiny notwithstanding the fact that individuals from a wide range of backgrounds execute the role. How the newly introduced HAIS scheme might change this position remains to be seen.

How then is diagnosis conducted? While intermediaries perform their own individual assessment, the ‘end user’ who has requested their services is often unsure of the nature of the individual’s vulnerability. The police officer or the instructing solicitor will have flagged a potential vulnerability - albeit based on limited professional knowledge or expertise of communicative disorder (Pearse, Reference Pearse1995; Dehaghani, Reference Dehaghani2019). Therefore, by the time a referral reaches an intermediary, an informal type of diagnosis has already taken place. It was concerning how little those intermediaries I interviewed knew about this process since their involvement officially begins when they are ‘matched’ to a case. Despite evidence of ad-hoc training organised by some regional police forces, there is no nationally co-ordinated effort to determine how intermediary training of police may improve effective screening of individuals with communication problems. A ‘triage’ system, whereby intermediaries provide telephone advice to police when screening, has been suggested by Pettitt et al. (Reference Pettitt2013), but has not been adopted by the MoJ or NCA. Unfortunately, even if an issue is flagged by police, there is often such poor understanding of the intermediary’s function among criminal justice professionals that vulnerable individuals are not given suitable support (Victim’s Commissioner, 2018, p. 26). One of the most problematic examples of this is police officers not knowing what the intermediary role involves and not requesting their services, even in cases involving very young children (Criminal Justice Joint Inspection, 2014; MoJ, 2014, p. 49). The MoJ Procedural Guidance Manual (2020, p. 13) recognises that no set procedure for assessments exists and that ‘the form and content … will depend on the witness’s communication needs and the Registered Intermediary’s skill set’. This guidance reflects the reality that intermediaries come from a wide variety of backgrounds and the differences in approach to ‘diagnosis’ were evident in my data:

‘It’s broader than most people initially think … it’s the conversations you have with the professionals who know that witness that will inform the needs they have and what strategies might help them outside the police interview and outside the courtroom, where they are at with their education … you’re looking at how they’re interacting with whoever has come with them, what means they are communicating by, how their body language appears, how anxious they are feeling.’ [E&W-15]

‘I have devised my own assessment which is very functional based. So, I start quite big and look at the environment that the person is communicating in now, how are they coping with distractions, what have they done to manage that environment … there’s a lot of fact finding at the beginning and I will use that information later in the assessment to test language and how they communicate and what kinds of questions or vocabulary, grammar might give them a problem.’ [E&W-2]

‘You can always read up on the nature of the person’s condition beforehand. Yesterday I was in a police station with an individual who was bipolar, had drug-induced schizophrenia and suffered from depression. Now, you could say “Where do you begin?” but really you begin by simply saying “look, will this person understand a question that is asked of them? Will they be able to process that and respond in a clear, logical and coherent manner?” The only way to know that is to ask them a question. Then you can add complexity to it until they reach a level where they can’t cope.’ [NI-2]

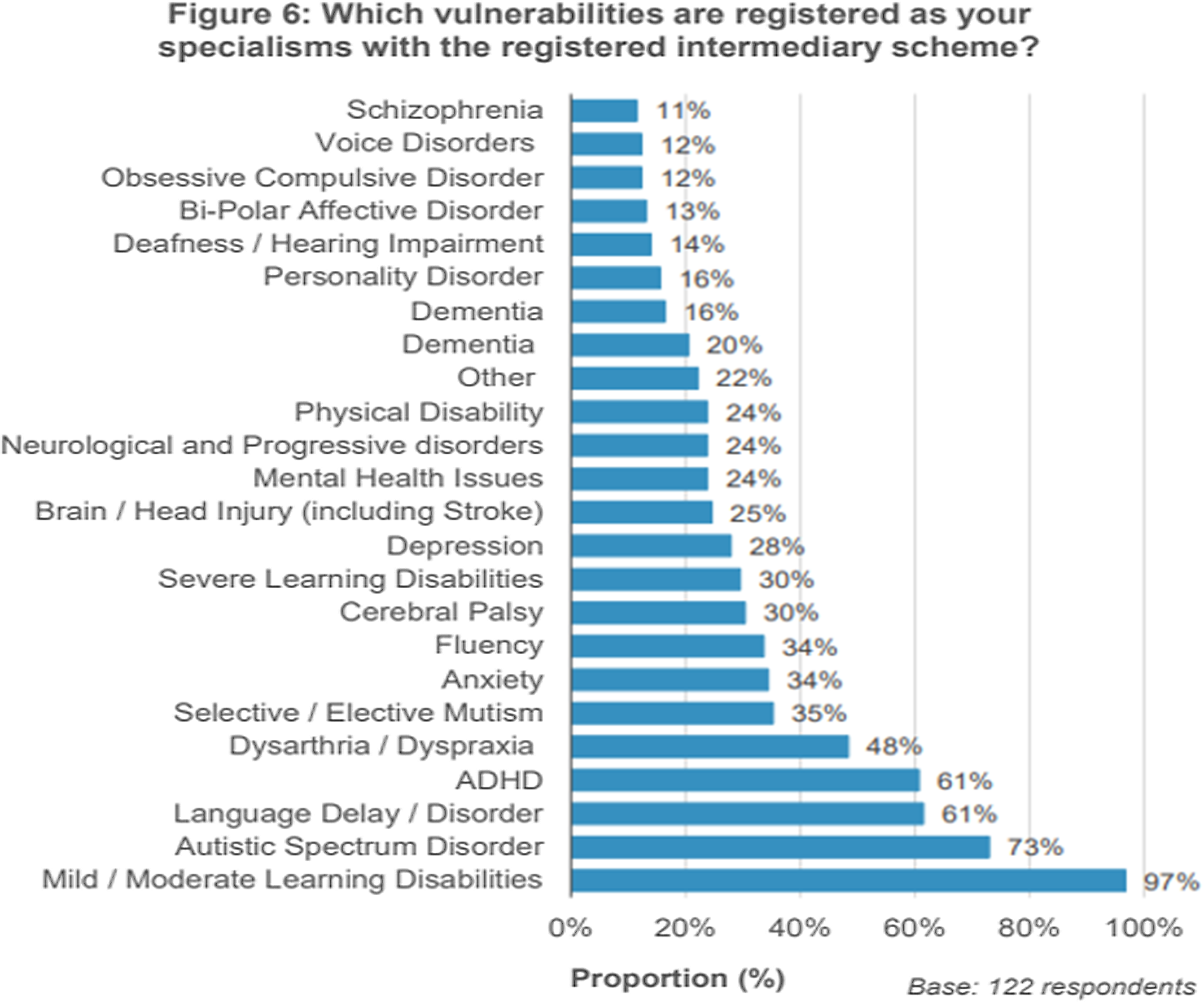

These three intermediaries hail from different professional backgrounds (social work, occupational therapy, and speech and language therapy) and demonstrate how the approach to diagnosing individual communication difficulties was inconsistent. This plurality of diagnostic techniques is not unusual per se, with Abbott recognising the ‘staggering complexity’ often involved with the task (Abbott, 1988, p. 41). Echoing this, Grimen (Reference Grimen, Molander and Terum2008, p. 71) identifies the theoretical foundations of professional knowledge as heterogenous rather than homogenous which rarely map onto one single academic discipline. That such a broad range of professional knowledge bases can be accommodated under the unifying role of ‘intermediary’ is, therefore, perhaps unsurprising. Indeed, the need for a heterogenous skillset among intermediaries is obvious based on how the NCA matching service operates. Cases are matched based on four categories of ‘vulnerability’: i) children; ii) mental illness; iii) learning disability; iv) physical disability (MoJ, 2020). The broad range of skillsets possessed by intermediaries is represented in Figure 1 below which outlines the individual specialisms. Despite the spectrum of specialisms, gaps in the intermediary knowledge base still exist. In 2020/2021, a total of seventy-six requests lodged with the NCA were ‘unmatched’ due to the unavailability of a suitably skilled intermediary (MoJ, Witness Intermediary Scheme: Annual Report 2018/2019).Footnote 2 E&W-11 explained how, despite their willingness to accept a broad range of cases, their theoretical knowledge of an applied behaviour analysis programme known as ‘The Picture Exchange Communication System’ or ‘Pic Exchange’ was insufficient:

‘I was quite comfortable working with mental health, with kids who were ASD, with autism. I had a range so I said from the beginning: “look I’m happy to take any age” [but] there would be things that I’ve had to pass back. There were two assessments that came through where there were children who used pics, like the “pic exchange”, and then I had to hand those cases back.’

Figure 1. Specialisms of Registered Intermediaries (referred to as Figure 6 in original source).

Source: Victims’ Commissioner, ‘A Voice for the Voiceless: The Victims’ Commissioner’s Review into the Provision of Registered Intermediaries for Children and Vulnerable Victims and Witnesses’ (January 2018) 35. © Copyright, Victims Commissioner 2023.

These comments reflect the multidisciplinary theoretical content that constitutes the intermediary role. In other words, the particular requirements of a given referral from the NCA dictate what theoretical resources are required for the intermediary to be able to initially make a diagnosis.

However, there are inherent risks in the diagnostic process. The way in which individual problems are classified may damage the professional expertise the intermediary seeks to project. This expertise is particularly vulnerable when diagnosis is performed weakly and/or not clearly conceptualised. This, in turn, creates fertile conditions for ‘inter-professional poaching’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 44) which occurs when intermediary work is defined by another professional using its own terms. Concerns relating to a lack of diagnosis uniformity were raised by intermediaries, police and judges. In particular, a number of intermediaries from a traditional Speech and Language Therapy (SLT) background identified issues about how non-SLT intermediaries were diagnosing and classifying the problems of vulnerable individuals:

‘A speech therapist writes a report not only as a diagnostic tool but also “what should be done to deal with this” … I know a social worker who has no background in assessing communication. They would often ring some of us and they were talking about a Down syndrome boy with a learning disability. They told me what was wrong with him and they have an innate sense of how to assess someone, but they just don’t know the terminology.’ [NI-7]

One intermediary with a background in occupational health was acutely aware that her own techniques did not match up with a typical SLT assessment:

‘[Speech and Language Therapists] are very language focused like “12 words in a sentence” whereas I don’t really bother with any of that … I usually read a little story and then ask them questions about it, so I get the chance to test all the language things. I test to see if I suggest something will they go along with it, I get some people to describe a family member to see if they can generate information … I’ve got an assessment of interaction skills which I use quite often which is an Occupational Therapist assessment and it’s like a score out of 4.’ [E&W-10]

Notwithstanding these comments, most intermediaries expressed real interest in knowing how their colleagues conducted assessments. But the solitary nature of the role and lack of peer review, particularly for defendant intermediaries, means that individualised practices appear common.

While defence solicitors must flag potential communicative issues in suspects and defendants, there was no obvious attempt by these legal practitioners to interfere with the intermediary assessment. The reasons for this may be numerous, but one that was cited by several intermediaries relates to the issue of neutrality, i.e. many defence solicitors view the engagement of an intermediary as a distinct benefit ‘because their client appears more vulnerable’. [NI-6]. There seems to be less desire to undermine the jurisdictional claim of intermediaries over assessment when the role is viewed as an ally or an asset. Colley and Guéry (Reference Colley and Guéry2015) found similar experiences among public service interpreters in their interactions with ‘service users’, such as police and prosecutors. These ‘service users’ were often indifferent to notions of impartiality and desired allegiance from interpreters whom they viewed as ‘tools’ (Colley and Guéry, Reference Colley and Guéry2015, p. 121) to assist their own work. My data suggests that being viewed instrumentally by defence solicitors in this way makes intermediaries feel that their expertise and theoretical knowledge is recognised. According to several intermediaries, reactions from police at the assessment stage were often starkly different. Police were more likely to view the intermediary as an encroachment on their ability to plan and structure the subsequent interview as they wished. Defence lawyers, conversely, appear primarily concerned with what is best for their client during interview.

Ordinarily, an intermediary will assess a suspect/defendant alone with the instructed lawyers present, and so the risk of external interference is minimised. This contrasts from other criminal justice settings, particularly the courtroom, where a process termed ‘workplace assimilation’ occurs. This involves a form of knowledge transfer where other subordinate professionals, non-professionals and members of related professionals ‘learn on the job a craft version of [a] profession’s knowledge systems’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 67). This concept is important for all intermediaries (whether working with witnesses or defendants) and a key question emerges: are other criminal justice actors able to acquire aspects of intermediary work so as to undermine the role’s exclusive jurisdiction? This is a significant question for the future development of both roles. For example, if defendant intermediaries can retain more jurisdictional control over work tasks than Registered Intermediaries, what might this mean for the sustainability of both roles in the criminal justice system? The section below entitled ‘jurisdictional settlement’ probes this question further.

One final point about diagnosis deserves attention, and it is of potentially existential importance for intermediary claims to exclusive jurisdiction. It relates to the systems put in place by the MoJ to ensure that Registered Intermediaries are sufficiently trained prior to being matched in a case. A senior intermediary, who is also a registered trainer, was critical of the MoJ recruitment process for new recruits, claiming that many lacked the basic assessment skills:

‘… as a training team we wondered why we had people on our course who didn’t seem to have some of the basics and we looked at the interviewing, why were some people being put forward for interview? So, we don’t do the sifting, the MoJ do it and they don’t know what they are doing and so we then went even further back and looked at the wording of the interview and that’s when we spotted they have taken out the necessity of having a degree and being a professional.’ [E&W-7]

E&W-7 accepted that non-SLT Registered Intermediaries would be ‘up in arms’ about their comments. But their view indicates a fear which many intermediaries share: that the credibility and legitimacy of the intermediary role would suffer should it not be recognised as a profession with consistent standards. As noted in the introduction to the chapter, many intermediaries echoed this desire to attain professional recognition. The call for training to be standardised in the way E&W-7 suggests mirrors Abbott’s argument that ‘the more strongly organised a profession is, the more effective its claim to jurisdiction’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 82). Inconsistency, or indeed incompetence, in diagnostic methods not only threatens the role’s relative standing but it also damages the ability to isolate assessment/diagnosis as the intermediary’s ‘exclusive area of jurisdiction and expertise [and] a legitimate area of knowledge’ (Fournier, Reference Fournier and Malin2000, p. 69). The fact that defendant intermediaries lack a standardised training scheme means that assessment technique is much less likely to be consistent and this was evidenced by the responses in interview. In fact, it was a surprise when one intermediary with considerable experience working with both witnesses and defendants described the latter work as ‘the Wild West’:

‘The “Wild West” analogy is quite a good one. I love it, absolutely love it. Given the choice if I had to pick defendants or witnesses I would pick defendants because it suits my personality better. I don’t like being told what to do and you are much more your own boss.’ [E&W-13]

E&W-13 was one of four intermediaries who explained that they preferred defendant work over witness work. Yet practitioner satisfaction does not necessarily equal strong jurisdictional claims over work. Based on Abbott’s argument that claims to jurisdiction are more effective when a profession is well organised, it follows that defendant intermediaries are less able to compete for legitimacy. While E&W-7 identified deficiencies in Registered Intermediary assessment capabilities, training has at least been updated to ensure basic assessment competencies are met. For defendant intermediaries, there is no equivalent organisation to centrally organise such training. Through an inability to control its members and collectively respond to any threats to its jurisdiction, defendant intermediaries seem to lack the ‘cultural machinery for jurisdiction’ (Abbott, 1988, pp. 82–83). An example of the distinction in organisation between the two groups is the ‘Registered Intermediary Procedural Guidance’ which is published and updated by the MoJ. While affording discretion in terms of assessment format, this document nonetheless acts as a reference point for the diagnostic elements of the intermediary role. The lack of similar guidance for defendant intermediaries exacerbates the lack of confidence many feel performing the role. Despite the recent establishment of HAIS, there is still no equivalent procedural guidance for defendant intermediaries.

As this section has revealed, intermediaries execute their diagnostic function primarily through assessment of the vulnerable individual’s communication needs. The assessment ‘assembles’ these needs into a picture so the intermediary can place the individual into the proper diagnostic category (Abbott, 1988, p. 41). The next section examines the second aspect of professional work, namely ‘inference’.

6.2 Inference

The second element of Abbott’s tripartite professional work model is ‘inference’. Abbott (1988, p. 40) considers inference to be the principal component of professional work which ‘takes the information from diagnosis and indicates a range of treatments with their predicted outcomes’. In other words, inference links diagnosis and treatment through application of expert, theoretical knowledge (Burris, Reference Burris1993, p. 119). In the case of the intermediary, the overlaps between inference and treatment are obvious. During the assessment, the intermediary is required to utilise their professional knowledge to diagnose any communication problems and decide whether the involvement of an intermediary is appropriate. While the presentation of the recommendations to the police or the court will follow, the act of inference take place at the assessment stage.

The action of inference raises a number of issues related to the intermediary’s professional jurisdiction. Unlike a solicitor who may meet a client at a consultation, the intermediary relies exclusively on other actors for the initial details of a vulnerable individual. In the case of a witness, the matching process overseen by the NCA will pair the Registered Intermediary with the person based on their experience and expertise. Contact will then be made with the relevant police officer in the case who will often provide further details and clarify that the Registered Intermediary has the necessary skill-set. For suspects or defendants, intermediaries are almost exclusively contacted by the instructing solicitor (MoJ (2021) Court Appointed Intermediary Services, Market Engagement).Footnote 3 Yet, even if a suspect/defendant has received a prior diagnosis, the solicitor may not be aware of this and the opportunity to engage an intermediary at first instance may be missed. The recommendation to engage an intermediary for a defendant may often arise out of the defence commissioning a psychological report (Plotnikoff and Woolfson, Reference Plotnikoff and Woolfson2015, p. 257). The failure of police, lawyers and others to identify vulnerability early on means that the intermediary may often never become involved in a case where they are needed (Gudjonsson et al., Reference Gudjonsson1993; Dehaghani, Reference Dehaghani2017). For both witnesses and defendants, the intermediary is required to make a judgement call, not about the appropriate ‘treatment’, but whether they are sufficiently skilled individually for the task based on the initial diagnosis of another. This creates a problem for the intermediary as E&W-20 explained:

‘Recently I had a case allocated to me on the basis of mental health and I made some initial enquiries of the officer and I formed the opinion that the difficulties that were going to be the barrier to communication were not the mental health issues which I thought were more suited to SLT and I recommended that the case be re-matched. I spoke to the officer about my thoughts and said … I think it would be better matched to someone [with] a different skill set. So, I handed it back to the matching service.’ (E&W-20)

In fact, this example gives an insight into the diagnosis, inference and treatment components of the intermediary role. A police officer had presented a vague case of mental health problems to the intermediary who sought further information in a bid to diagnose with more certainty. Concurrently, a self-diagnosis was taking place where the intermediary had to decide if they were competent to assess the individual. The intricacies of this latter process are understandably complex and rely on the subjective value judgements of individuals. Focal to this self-assessment is what E&W-20 termed ‘being absolutely boundaried’ as to one’s competencies. As Riesch (Reference Riesch2010, p. 454) notes, construction of boundaries essentially amounts to professions seeking to ‘communicate their subject [and] establish their own credibility to talk authoritatively about their subject’. By only accepting referrals which match their skill-set, E&W-20 strengthens rather than weakens their authority and credibility over their work. Further, this form of boundary work encourages intermediaries to be reflective about their own knowledge claims and resist spreading their jurisdictional net so wide to make it a target for criticism.

While E&W-20 commendably returned the referral, it seems that intermediaries find themselves in a veritable ‘Catch 22’ situation. On the one hand, those who accept complex referrals (for which they may potentially be underqualified) and make recommendations accordingly may conduct ‘too little inference’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 51). This involves a seamless movement from diagnosis to treatment. The problem with this approach is that it becomes an obvious target for poaching by other professions. If there is a routine, ineluctable link between diagnosis and treatment then why do we need intermediaries at all? The task could be conducted by existing members of the criminal justice system and the activity would arguably not warrant specific professional status (Burris, Reference Burris1993). On the other hand, too much ‘formal inference’ involving intermediaries applying their professional knowledge to the presented diagnosis in more obscure cases, is dangerous. This is because of the risk that the overall activity is perceived as a ‘mass of personal judgements, well informed, but ultimately idiosyncratic’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 52). Further, a profession that frames itself in purely abstract terms faces difficulty in demonstrating what Abbott terms ‘cultural legitimacy’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 54).

The mutually conflicting scenario described above was well understood by every professional group interviewed. There was a palpable sense of unease among many intermediaries who saw opportunities for other actors, particularly members of the court workgroup, to undermine the role’s credibility and legitimacy. One particular quote encapsulates this:

‘I feel that all those dichotomies going on and there is “divide and conquer” and that is how judges and barristers are going to get you in the end.’ [NI-7]

This language illustrates the unease with which many intermediaries regard their role and its susceptibility to attack. It also aligns with Abbott’s conception of jurisdiction as competition with malleable jurisdictional boundaries waiting to be capitalised upon by other predatory professions. The professional activities of individual actors in any system of work cannot be unilaterally defined and determined but are rather subject to the dynamics of interdependent relationships (Timmermans, Reference Timmermans2002). Yet, the above quotes from E&W-20 and NI-7 suggest a cognisance of this threat and a willingness to react. In particular, E&W-20 places the responsibility on intermediaries to engage in introspection, not just to ensure more appropriate matching, but to protect the role’s professional jurisdiction within the ‘ecology’ of the criminal justice system (Abbott, 1988, p. 33). E&W-20’s clarion call can be viewed as a response to the threat of workplace assimilation which Abbott (1988, p. 66) notes ‘reaches its maximum in publicly funded worksites specializing in pariah clients - mental hospitals, jails, criminal courts’. This assimilation may involve the police, lawyers, and judges appropriating intermediary tasks based on perceptions of incompetence. Backen (Reference Backen2017, p. 63) identifies another catalyst for this assimilation: intermediary reports which do not recommend intermediary involvement at all are never seen by judges or lawyers in a case. As a result, there exists a skewed view of how the intermediary performs its core professional tasks and, crucially, how they recommend their involvement. Without seeing reports in which intermediaries justify their non-involvement, how can judges understand the theoretical knowledge and expertise underpinning diagnosis, inference, and treatment? Many intermediaries interviewed echoed this point and felt that lawyers and judges were oblivious to their ‘backstage’ role during assessment. Citing previous research conducted by Communicourt (2020), E&W-17 claimed that 24 percent of all intermediary assessments conclude with a recommendation of no intermediary involvement. E&W-17 also lamented the judicial perception of the intermediary as primarily self-serving and ‘on the make’:

‘They don’t want to know if we recommend [intermediary involvement] because we’re “self-serving” aren’t we? We’re appointing ourselves! We’re “desperately looking for work”. I could be in three other courts today. There’s no shortage of work! But they think we are looking for work for ourselves!’ [E&W-17]

The above analysis suggests that intermediaries are conscious of ongoing jurisdictional conflicts and are often prepared to confront them. But beyond individual practitioners voicing their views, can jurisdictional conflicts be resolved systemically? Abbott (1988, p. 83) notes that in inter-professional jurisdictional contests ‘the profession with more extensive organisation usually wins’. It is axiomatic that a strong, co-ordinated response to jurisdiction threats requires an organised professional body or, at the very least, a figurehead. As noted above, no group of intermediaries currently has such a body or lead individual. It is difficult to see how the intermediary, already an outsider, can compete with established members of court workgroup in such conditions. Further, the newly established HAIS scheme effectively bifurcates the intermediary community into ‘Registered Intermediaries’ and ‘Defendant Intermediaries’. Such division of roles does little to foster a united front and surely weakens intermediaries as a collective occupational group (Taggart, Reference Taggart2022).Footnote 4

The act of inference is, according to Abbott (1988, p. 40), a ‘purely professional act’. As we have seen in this section, for intermediaries, the act of inference is the link between the diagnosis of communication issues and relevant treatment and is closely tied to how jurisdictional claims are made and defended. The next act constituting professional work is treatment.

6.3 Treatment

The third component of professional practice is ‘treatment’. Abbott’s conception of treatment is self-evident and refers to methods to remedy problems or complications made apparent from the diagnosis. Like diagnosis, it is organised around a ‘classification and brokering process’ which gives a result rather than taking information (Abbott, 1988, p. 44). Unlike some professions, the intermediary advises the most appropriate treatment rather than administering directly. The treatment suggested by the intermediary is embodied in the reports compiled for police prior to interview (if involved at that stage) and then later for the court, if required (MoJ, 2020). This latter, and more substantial report, should include the witness’s background, the ‘diagnosis’ from the assessment and ABE interview, the witness’s communication abilities and specific needs together with practical suggestions about how the witness can best be questioned at court (MoJ, 2020, p. 16). These essentially amount to instructions, or ‘practical precepts’ (Sciulli, Reference Sciulli2009, p. 350) which are premised on academic work and theoretical principles.

Outlining recommendations in the form of ‘treatment’ is a potentially hazardous area for the intermediary with a risk of ‘outside interloping’ into its professional jurisdiction (Abbott, 1988, p. 45). In other words, the efficacy of treatment, as judged by external actors such as police, lawyers and judges, is critical to how the intermediary role is perceived and how it gains legitimacy. The quality of recommendations, whether given directly to the police orally or in written form to the court, was a contentious topic in my interviews. Whether taking responsibility for another intermediary’s case or being asked to provide advice on another Court Report, some intermediaries were concerned about the quality of recommendations. For example, when reviewing another Registered Intermediary’s preliminary report, NI-7 was shocked to find ‘32 points for the police’ to follow in a suspect interview. This was, in her view, overly complicated and ran the risk of damaging the image and reputation of intermediaries in general.

A similar concern, voiced by some judges in Northern Ireland, lamented the generic nature of the court reports:

‘Sometimes, some of the reports I have had I have thought: “I could have worked that out myself” and that might sound arrogant and I don’t mean that. But those are strategies that I think we already have.’ [MCJ-2]

‘They were kind of generic I have to say which detracts from them to some extent because you feel that it’s a “tick-box exercise”. I would like to see something a bit more individual and I think it gives it more weight.’ [CCJ-1]

Another judge responded almost identically:

‘The reports that I have been getting, quite often I find myself apologising as I say to the defence: “That all seems to me to be common sense” and then I always have to apologise because I know there is expertise and all the rest of it, but most of us can see when a child is getting stressed and needs a break.’ [MCJ-1]

CCJ-2 conveyed a less critical judicial tone about intermediaries’ recommendations but remarked that they are ‘usually fairly pedestrian [and] rarely differ’. Yet, the tone of these responses signals a potentially serious credibility issue concerning the confidence that other key criminal justice actors have in the recommendations of intermediaries. There were, of course, many intermediaries who had not experienced any adverse comments or attitudes from police, lawyers, or judges regarding their recommendations. Further, some intermediaries were surprised when the above judicial perspective was presented, with a number becoming noticeably defensive. One wonders whether a much more serious discord exists between intermediaries, the police, and judges about the appropriateness of recommendations. A practice that appears to aggravate the situation is the failure to allow intermediaries to explain their recommendations to the court in a GRH. The requirement to hold a GRH is contained within the relevant Criminal Practice Directions 2015 (para. 3E.2), Criminal Procedure Rules (rules 3.9(6) and (7)) and in the Judicial College guidance (2022). Plotnikoff and Woolfson (2019, p. 81) found that only 30 percent of Registered Intermediaries were almost always asked to discuss their recommendations at a GRH, whereas 95 percent of judges said they almost always invited intermediaries to discuss key recommendations. This discrepancy is not easily explained but is nonetheless evidence of a disharmony between judges and intermediaries. Most intermediaries had at least one experience of no GRH taking place in a case, but when it did the minimisation of their role was evident:

‘You don’t as a Registered Intermediary ever get asked for any knowledge, half of the time you don’t get to open your mouth in a GRH. The longest GRH I had was 20 minutes. The shortest was about 30 seconds and I didn’t even get in the box. It varies very much from judge to judge.’ [E&W-13]

‘An effective GRH only needs to be 15mins or something. But I do think I need to be given an opportunity to speak. But when the judge says “Yes we have read your report and will follow your advice” and that’s it, that leaves you no room for questioning anything because the assumption is you are going to move on to the next thing to discuss.’ [E&W-8]

While most intermediaries spoke of an improving judicial attitude to GRHs, E&W-2 recounted a shocking judicial response to her attempt to explain her recommendations:

‘the law has changed and we have to have you here now, but I am not impressed. I have seen your report, you’re trying to tie counsel’s hands behind their back and if you intervene I will hold you in contempt of court.’ (E&W-2)

This quote reveals conflict between intermediaries and the court workgroup over treatment. Recommendations in the court report can be viewed by lawyers and judges as no different to what has been practiced for years, with the intermediary role merely committing age-old techniques to a paper report. This differs from the experience of other therapeutic agents, such as probation officers, who have become embedded into the institutional arrangements of judicial institutions such as problem-solving courts (Young, Reference Young2013; Konecni and Ebbesen, Reference Konecni and Ebbesen1982). For example, research into American drug courts found that probation officers often wielded a ‘substantially superior level of power when compared to other court team members’ which in turn substantially influenced case outcomes (Rudes and Portillo, Reference Rudes and Portillo2012; Castellano, Reference Castellano2009). My data suggest that the court workgroup is often reticent to acknowledge treatment recommended by the intermediary. This seems, at least partially, to be based on a lack of understanding of the theoretical basis of recommendations and a belief that the court workgroup can facilitate communication without intermediary assistance. These conclusions support the above suggestion that a discord exists between intermediaries and the court workgroup in terms of how the treatment function of the intermediary role is conceptualised and indeed approached in practice.

7 Jurisdictional settlement

As discussed above, intermediaries are conscious of incursions into their jurisdiction and often struggle with how they can sustain control. Yet it is possible that by being part of a ‘culture change’ towards the improved treatment of vulnerable witnesses and defendants, intermediaries are hindering their integration into the established cohort of criminal justice actors. This notion was first suggested to me by an intermediary in Northern Ireland who argued that the profession should be ‘working ourselves out of a job’ (NI-2). They explained how in five or ten years’ time lawyers and judges should have learned sufficiently from the practice of intermediaries that the role should be minimised. Many intermediaries whom I subsequently interviewed were appalled by this suggestion and argued that it betrayed a lack of understanding of the role. However, there is an alternative analysis of this view. While ostensibly advocating a narrower, more nuanced role for the intermediary, NI-2’s comments reflect an attempt to protect the role’s jurisdiction in the long-term. This implicitly involves a form of boundary work in which, rather than seeking ‘expansion or authority’ into a domain claimed by another professional, the intermediary’s goal is ‘protection of autonomy’ (Gieryn, Reference Gieryn1983, p. 792). Unlike E&W-17 and E&W-7, who advocated for increased intermediary involvement at all stages, NI-2’s comments are suggestive of what Abbott (1988, p. 575) terms a ‘jurisdictional settlement’ between intermediaries and other actors in the criminal justice system. While Abbott details five distinct types of jurisdictional settlement, NI-2 appears to suggest an ‘advisory jurisdiction’ for intermediaries. This involves intermediaries accepting a ‘weaker form of control’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 75) which sees other actors eventually claiming aspects of the intermediary’s current jurisdiction. The amendments to the Criminal Practice Directions (2015) and the subsequent case of R v. Rashid ([2017] EWCA Crim 2) signalled a restriction to the availability of defendant intermediaries. These developments could be viewed as evidence of an advisory jurisdiction in practice as judges are expected to ‘adapt the trial process to address a defendant’s communication needs’ ([2017] EWCA Crim 2 [73]). Further, the court emphasised the ‘training and experience’ of the defence advocates who should be expected to carry out the ‘basic tasks’ of asking questions is clear and simple way ([2017] EWCA Crim 2 [80]).

Abbott (1988, p. 75) notes that advisory jurisdiction involves a profession seeking a legitimate right to ‘interpret, buffer or partially modify actions another takes within its own full jurisdiction’. In practice, this could arguably involve intermediaries providing more general recommendations about how to facilitate communication without the sort of ‘hands on’ involvement the role often currently involves. For example, a written report about the vulnerable individual, which the court could use as it wishes, may amount to an advisory jurisdiction. The intermediary may not even be physically present at any stage save for the assessment at the outset. Paradoxically, NI-2 views this diminution of the intermediary’s jurisdiction as inevitable but ultimately necessary for the role’s survival. However, the judges interviewed were largely cautious about the idea. While some judges acknowledged that the intermediary had forced the judiciary to be ‘more alert and aware of the issues that defendants and witnesses may have’ (MCJ-2), this did not mean that the role should be phased out:

‘The intermediary is bespoke to that particular client’s needs so whilst I, as the lay person, think I am terribly clever and know a lot about autism and don’t need the expert because I have a handle on this, when you get the particular individual it’s how that condition manifests itself with that particular person in the particular circumstances and the stress you are going to put them under. For those reasons you will still need intermediary expertise.’ [MCJ-2]

‘It could well be that we get to a point where, if everyone is on the same page, then there is less need for an intermediary because the questioning is appropriate and the judges are more informed … If we are doing it properly, their role ought to diminish and they should be self-limiting to a large degree … But I would be worried about a degree of complacency where we say: “oh that’s not needed at all now, we know everything about this”.’ [CCJ-1]

Professional competition over jurisdiction can produce various outcomes since not every profession aiming for full jurisdiction will obtain it. If advisory jurisdiction is indeed the outcome of the intermediary’s jurisdictional disputes, a salient question is whether this amounts to the ‘leading edge of invasion [or] the trailing edge of defeat’ for intermediary work (Abbott, 1988, p. 76). At such an early stage in the role’s development this is a difficult question to answer conclusively. However, crucial to the outcome will be the intermediary’s ability to communicate its exclusive authority over its workplace tasks and the acceptability of the role’s professional boundaries to other criminal justice actors. This reality is reflected in the comments of judges included in this article. The generally sanguine judicial perception of intermediaries and their work appears a good augury for the role’s future. Notwithstanding positive signals from some judges and lawyers and the fact that many recent recruits appear to have settled on the role as a full-time profession, the role’s parameters and claims to jurisdiction have been shown to be far from settled. Questions remain about how willing key criminal justice actors are to accommodate the ‘professional work’ of the intermediary and how disputes over jurisdictions and boundaries will be settled.

8 Conclusion

Henderson (Reference Henderson2015, p. 155) has described the intermediary as the ‘first new, active role to be introduced into the criminal trial in two centuries’. This article has explored how this newcomer interacts with the professional world of the criminal process and how this impacts the nature and scope of its work. Drawing on the work of Abbott and Gieryn, we have seen how intermediaries tussle for control over the role’s work tasks with other criminal justice actors. Through diagnosis, inference and treatment, the intermediary performs professional work which is relational at its core. Interaction with other criminal justice actors shapes the role’s content in several ways. It enables the intermediary to demonstrate its theoretical knowledge and expertise to persuade audiences of its jurisdictional claims. Equally, other professionals scope out the role and often question its legitimacy. My data reveal the resistance of the court workgroup to threats challenging its cultural norms and how intermediaries often tread a thin line between gaining acceptance and seeing their jurisdiction vulnerable to encroachment. Fundamental to understanding the nature of these inter-jurisdictional conflicts are boundaries. Boundaries act to mediate inter-professional interaction and delineate the intermediary’s tasks, which is key to understanding how the role is located within the criminal justice system. Although the scope of the intermediary role was initially untested and often unclear, individual practices have seen the construction of boundaries which are continually negotiated between actors.

While this article has given a snapshot of the intermediary’s professional work, the question of where these interjurisdictional disputes will lead remains. In other words, what will be the resulting ‘outcome’ or ‘settlement’ of these jurisdictional conflicts? It is through interaction with the court workgroup that the intermediary claims jurisdiction and seeks legitimacy and so any eventual settlement will depend on the acceptance of the claims (Abbott, 1988). If the objective is for the intermediary role to retain control over its workplace tasks, then much will depend on how inter-professional jurisdictional disputes are settled and how associated boundaries are negotiated. Ultimately, whether the role becomes further integrated into the criminal process or, conversely, will see its scope and function reduced, is firmly tied to securing exclusive jurisdiction through knowledge claims and the corresponding perception of its ‘professional work’ among the court workgroup.