The current study uncovers two overlooked early formations of Buddhist social consciousness in India and China by analyzing three modern retellings of an ancient Buddhist love story between an outcasteFootnote 1 girl and the Buddha's assistant Ānanda: the 1856 draft of an unproduced opera Die Sieger by Richard Wagner, the 1933 dance drama Chandalika by Rabindranath Tagore, and the 1927 Peking opera Modengjia nü 摩登伽女 penned by the playwright Qingyi Jushi 清逸居士 and produced by the opera performer Shang Xiaoyun 尚小雲. I argue that the surprising modern popularity of this ancient love story lies in its forceful social critique. Throughout history, this ancient Buddhist romance has been retold many times in diverse forms and thus has accrued multiple meanings. However, in premodern settings, the meaning of this story hinged crucially on the Buddha's unparalleled salvific power. Only in modern times, at the margins of the colonial empire, did this love story metamorphosize into a quest for justice and simultaneously merge Buddhist spiritual inclusiveness with social equality. Consequently, two new formations of Buddhist social consciousness emerged during the Buddhist revivals in India and China. This article traces these theatrical afterlives of the Buddhist love story, unveils overlooked cultural exchanges, discloses diverse meanings of being Buddhist, and compels scholars to take seriously the Buddhism-inflected alternative modernities in both India and China.

This comparative study makes two interventions. The historical intervention is to showcase a shared socio-spiritual horizon in the Buddhist revivals in India and China. I argue that while the colonial condition was the backdrop for both nations' Buddhist revivals, the revivalists in both countries took advantage of the Buddhist spiritual quest for equality and freedom to advance their respective egalitarian agendas: anti-caste in India and anti-patriarchy in China. By examining two endogenous social visions side by side, this study draws scholarly attention to alternative future trajectories opened up by these cultural productions and analyzes alternative theorizations of an equitable society.

Methodologically, this study experiments with one strategy of dismantling the remnant productive power of colonial discourse: decoupling the putative binary of Western universals and Eastern particulars. More concretely, in this study, I examine how historical actors produced and employed cultural soft power such as plays and dramas to upcycle ancient quest for freedom and equality as tools to establish an egalitarian, modern society. In doing so, I foreground overlooked Chinese and Indian perspectives on universalism and cultural pluralism. Postcolonial scholars have long exposed colonial discourse as an apparatus by which to produce knowledge of the colonizer and the colonized. Such knowledge is subsequently employed by the colonial powers to police the constructed boundary.Footnote 2 However, as inheritors of colonial knowledge production, disciplinary gatekeepers and scholars trained under this colonial legacy are still struggling to overcome the remnant power differential and epistemic domination.

The current study suggests one way for scholars to disrupt an enduring mechanism for reproducing the colonial power differential; namely, the tendency to equate Western formulations of freedom and equality with universal values and to dismiss Eastern formulations of the same as local, particular responses. I suggest that to break free from this presumed binary, scholars take seriously the epistemic advantage of knowledge producers situated on the receiving end of the colonial discourse. In making this argument, I adopt the perspective of Asian artists who exposed the falsity of the colonizer's claims to universalism, who countered the colonizer's putative universals with their own claims to universal values, and whose cultural productions allowed them to reclaim the narrative and define freedom and liberty on their own terms.

More concretely, the first step is to recognize the remnant colonial power in existing studies of the modern afterlives of the outcaste girl Prakriti. Although Wagner, Tagore, and Shang Xiaoyun dramatized the same Buddhist story within a few decades of one another, scholars have not considered the retellings on equal footing. In the field of Buddhist studies, Wagner's unfinished opera scenario has received detailed scholarly treatment.Footnote 3 Tagore, however, has been mentioned only in passing.Footnote 4 Shang Xiaoyun's play remains unstudied in English-language scholarship to this day. In the field of literary studies, many scholars have examined Tagore's Buddhist-themed dramas from the angle of the New Woman, literary innovation, and the new spiritual discourse of universal love.Footnote 5 Similarly, Chinese scholars have analyzed Shang Xiaoyun's play in relation to its Buddhist past, the emergence of modern Chinese literature, and the formations of the Chinese New Woman.Footnote 6 To date, however, there is only one Chinese study that brings into conversation Tagore and Shang's theatrical recreations of the Buddhist outcaste girl through the lens of literary critique.Footnote 7 Scholars have yet to combine both literary analysis and Buddhist studies to fully unpack the significance of Tagore and Shang Xiaoyun's creative forces in popularizing alternative visions of equality and freedom.

The second step is to acknowledge that, to correct this scholarly oversight, scholars have a responsibility to go beyond the confines of the colonial structures of knowledge production and instead pay attention to Tagore's and Shang Xiaoyun's creativity and contributions to making Buddhism modern.Footnote 8 Historically, other than those interested in Chinese Buddhism and trained in Sinology, few Buddhist studies scholars have felt the need to master classical Chinese on top of Sanskrit, Pāli, and classical Tibetan. Similarly, literary scholars of modern Asia have tended to focus on the impact of Western modernity on Asian literary movements and thus overlook the complex roles of Buddhism in domesticating the imported concepts of liberty and equality. Generally speaking, scholars trained in both disciplines are required to learn several modern European languages while specializing in one of the following areas: East Asia, South Asia, or Southeast Asia. Consequently, scholars who wish to master the languages of two Asian cultures, such as Sanskrit and classical Chinese, must overcome additional academic obstacles. Thus, the existing disciplinary structures produce scholars who are ill-prepared to examine the role of Buddhism in intra-Asian cultural exchanges in modern times. Fortunately, despite these disciplinary constraints, scholars in the past decade have made great strides toward a deeper understanding of the Buddhist past by heeding to new intra-Asian dynamics.Footnote 9 Looking through the eyes of Asian artists, the current research provides one concrete means of provincializing Europe by highlighting the vibrant social imaginations circulating in Asian cultures outside the fold of Western political modernity.Footnote 10 Simultaneously, it joins the recent efforts to use the China–India comparison as a method to understand “the cultural history of modernity.”Footnote 11

My findings demonstrate how Tagore and Shang Xiaoyun nurtured the ancient Buddhist seeds of spiritual equality and universal salvation and gave birth to different forms of Buddhist social consciousness so as to stake out their own claims to univeralism. At the same time, my research delineates an ethics of persistence in these two Indian and Chinese cultural productions. On the one hand, Asian artists often had problematic associations with colonial structures of violence: the political domination of the British empire in India versus the economic domination of so-called “free trade” in China.Footnote 12 On the other hand, these artists took advantage of favorable modern conditions to realize the core values of equality and freedom in the Buddhist past and address pressing social issues. In doing so, they subverted Europe's self-presentation as the modernizer by presenting ancient Indian and Chinese cultures as already modern.

By centering the discourses of Asian knowledge producers, this comparative study illustrates the multi-layered powerplays that both constrained and were embedded in these public-facing attempts to reclaim the narrative about who is authentically modern. Consequently, this study captures how artists took up space and emphatically voiced their discontent despite their complicity in existing systems of oppression and their problematic participation in epistemic domination. Instead of dismissing these alternative visions as local imitations of the master narrative, this study takes seriously these alternatives, celebrates their creative upcycle of the ancient Buddhist quest for liberty and equality, and showcases Asian discourses of how to live with others without sacrificing differences and plurality and how to establish social bonds that ensure both individual and collective flourishing.

The structure of the paper is three-fold. In the first section, I introduce the colonial conditions surrounding the production and circulation of Buddhist knowledge about the ancient romance. I further situate Richard Wagner's opera scenario in this colonial circuit and show how Wagner's retelling dismisses the anti-caste consciousness found in the ancient story and instead incorporates misogynistic views to glorify an ideal modern individual implicitly modeled after a heroic male.

In the second and third sections, I showcase how the modern afterlives of this tale address the concerns and aspirations of the Indian and Chinese artists. By looking through their eyes, scholars are able to discover a shared socio-spiritual horizon that unsettles the conventional impressions of a spiritual India and a rational China. More specifically, in the second section, I analyze the anti-caste spirit in Rabindranath Tagore's dance drama Chandalika and contextualize it in relation to the Indian discovery of Buddhism in the modern era and concomitant struggle to overcome the caste system. I argue that the Buddhist social consciousness as embodied in Chandalika falls short of the playwright's own social goals because it uses Buddhist spirituality to reduce a complex socio-political issue into a psychological struggle.

In the third section, I examine the feminist quest in Shang Xiaoyun's modernist Peking opera Modengjia nü and unveil the cultural subtexts and the Chinese patriarchal anxiety of the early twentieth century. I argue that the success of the opera was partially because it successfully tamed the feminist quest of free love by the Buddhist spiritual awakening and thus soothed patriarchal anxiety about “unruly” female sexuality. Consequently, the Buddhist social consciousness as embodied in Shang's opera also lacks transformative potential. In fact, Shang retools Buddhist spirituality to suggest a “middle-way” compromise: On the one hand, his retelling affirms women's equal right to pursue free love; on the other hand, it quells “troublesome” female sexuality to appease contemporaneous patriarchal sensibilities.

Despite their different trajectories, both the Indian and Chinese theatrical afterlives of the ancient Buddhist story reveal a socio-spiritual horizon that sought to use the ancient Buddhist spiritual inclusiveness to wrestle with pressing social inequalities. In contrast to the Asian retellings that extend Buddhist soteriology for establishing social equality, Wagner's retelling reduces Buddhist soteriological quest into an individual's Bildungsroman and repackages Buddhist spirituality as a means of overcoming the angst caused by unrequited love. To gain a fuller understanding of the appeal of Buddhist spirituality in modern Asia and to appreciate the various ways the Buddhist past has been made relevant to social concerns, scholars need to conduct additional comparative studies of the Indian and Chinese Buddhist revivals. Thus, in the concluding section, I examine the promises and limits of cultural comparisons and point out future research directions.

One Buddhist romance, multiple transmissions

The story of the outcaste girl and Ānanda, Śārdūlakarṇa-avadāna (The Story of Śārdūlakarṇa), is a fascinating drama of love, anti-caste consciousness, and astrological maneuvers for worldly gains and spiritual awakening. In its earliest extant form, this story belongs to a compendium of Indian Buddhist narratives called Divyāvadāna (Divine Stories) that were probably compiled in the early centuries of the Common Era. Avadāna (story, legend; Ch: piyujing 譬喻經) is the genre of Buddhist moral education. For the purposes of this essay, it is important to note that many of the stories that fit this genre, including Śārdūlakarṇa-avadāna, originated from the Vinaya (monastic code) division of the Buddhist canon.Footnote 13 Such a story typically opens with an introduction of where and on what occasion the Buddha narrated the story of the past. At the close, the Buddha draws from the story the moral of his doctrine. Hence a regular avadāna consists of a story of the present, a story of the past, and a soteriological message at the end. The stories in Divyāvadāna were frequently used in the moral education of both monastics and the laity in premodern Asia. As these stories spread throughout Asia, they were recited and reworked. They were translated into multiple languages. They were also painted and sculpted in caves, murals, and scrolls.Footnote 14

Thanks to more than a century of Buddhological and philological analyses, we know that in premodern settings, the text of The Story of Śārdūlakarṇa existed in at least three versions: (1) a short version preserved in Pāli that became the basis for the first Chinese translations (T1300, T551, T552); (2) the complete Central Asian version preserved in the St. Petersburg collection that formed the basis of one Chinese translation (T1301) and a Tibetan translation; and (3) the complete Indian version that is preserved in a Nepalese manuscript.Footnote 15 In Buddhist studies, this text is well known for its inclusion of some of the earliest Indian astrological conceptions of constellations in the sky and their applications in healing, good governance, and wealth accumulation.Footnote 16

However, the story's modern afterlives in India and China remain understudied. In the following, I first recount the story in its premodern format as a foundation for understanding its modern variations. As a standard avadāna, it contains a story of the present (the forbidden love between the outcaste Chandala girl known as Prakriti and Ānanda), a story of the past (the debate between a brahmin and the king of the Chandala people on the meaning and validity of the caste system), and a moral message (the supremacy of the Buddha's teaching).Footnote 17 In the premodern versions, the basics of the present story about the Chandala girl and Ānanda goes as follows. One day, the Buddha's attendant Ānanda, born into a high caste and an ordained monk,Footnote 18 was out begging for alms. On his way back to his residence, he felt thirsty. Approaching a well, he found an untouchable girl named Prakriti (which means “Nature” in both Sanskrit and Bengali). He asked her to give him water. Simply by asking for water from an untouchable, Ānanda broke the caste rule that considers the touch of the outcaste as polluting to people of the higher castes. Prakriti fell in love with Ānanda. After she returned home, Prakriti begged her mother to cast a spell on Ānanda so that he would break his vow of celibacy and marry her. Prakriti's mother cast the spell; however, in the end, Ānanda was able to break the spell on him with the help of the Buddha. The lovestruck Prakriti followed Ānanda to the Saṅgha and pleaded with the Buddha to grant her wish to marry Ānanda. The Buddha, playing on the double meaning of “vow” as both a commitment to marriage and a commitment to ordination, admitted Prakriti into the Saṅgha. It is important to recognize that, in the premodern versions, while their acts transgressed the caste rule, neither Prakriti nor Ānanda directly challenged the caste system. Rather, the story explains their actions as indicative of the remnant attachment from their past lives as a married couple.

In the past story that explains the karmic inner-workings of this love lore, readers find extensive explanations of astrological strategies of healing, governance, worldly gains, and spiritual awakening wrapped in a metanarrative about the validity of the caste system. Because this part of the tale is missing in all its modern afterlives, I will not recount it in detail. However, the gist of the story is as follows. The king Prasenajit became furious when he learned that an outcaste was admitted to the Saṅgha and that high-caste individuals such as kṣatriyas and brahmins would need to show respect to a Chandala girl. To soothe the king's anger, the Buddha told him the past story. In one of his past lives, the Buddha was a king of the Chandala people, and Ānanda was his son, named Śārdūlakarṇa. Back then, Prakriti was the daughter of a learned brahmin. When the Chandala king asked the learned brahmin whether his daughter could marry the king's son Śārdūlakarṇa, the king and the brahmin began a lengthy debate on the true meaning of caste. In the end, the Chandala king won over the brahmin with his exhaustive astrological knowledge. He convinced the brahmin that knowledge and spiritual merit alone, not birth, should be the markers of a high caste. Because the debate was conducted by the Buddha in one of his previous lives, the moral message of the story is the triumph of the Buddha's superior knowledge. While this premodern story contains a strong anti-caste consciousness and sophisticated arguments against an unfair hierarchy, what has been highlighted again and again over its long history of transmission is the efficacy of Buddhist teaching in establishing worldly success and leading all toward salvation.

The exact reason why this past story is missing in all three of the modern afterlives of The Story of Śārdūlakarṇa is unknown. I will examine the transmission histories of the modern Indian and Chinese afterlives in the next two sections. The focus of the rest of this section is Wagner's encounter with this ancient story and its entanglement with the colonial production of Buddhological knowledge.

Wagner's reception of this story was interwoven with the empire of religion – the science of religion that was motivated by the imperial desire to classify and then subjugate and control colonized peoples.Footnote 19 In 1856, Wagner read a summary of the legend in Eugène Burnouf's Introduction a I'histoire du Buddhisme Indien (1844; henceforth: Introduction) and decided to write an opera scenario.Footnote 20 Burnouf had played a vital role in the founding of the scientific studies of Buddhism. Indeed, his Introduction is considered the most influential work on Buddhism written in the nineteenth century.Footnote 21 Burnouf wrote Introduction based on careful studies and selected translations of 147 Sanskrit manuscripts first found in Nepal and then dispatched to Paris. Introduction inaugurated Buddhism as a textual object of European philological studies.Footnote 22

Wagner's encounter with this story was intimately connected to the European study of Buddhism as a textual object. For Introduction, Burnouf penned a summary-cum-translation of The Story of Śārdūlakarṇa based on the Nepalese manuscript, accurately retelling the present story, the past story, and the moral message but omitting all details about astrology.Footnote 23 He also paid little attention to the love story. For Burnouf, the significance of this story lay in its anti-caste consciousness: The Buddha-cum-Chandala king attacked the caste system at its base and turned the system on its head.Footnote 24 At first sight, it is refreshing to see Burnouf celebrating the Buddha as a social reformer and a freedom fighter. However, scholars must take into account the cultural subtexts of Burnouf's retelling. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European colonizers liked to depict the Hindu caste system as frozen in time and the epitome of religious oppression, utterly in contradiction to the European Enlightenment ideals of equality and freedom.Footnote 25 The colonizers constructed Buddhism, which had already disappeared in colonial India, as the counter-image of Hinduism and compatible with the Enlightenment ideals. Viewed in terms of this colonial epistemic domination, it is difficult to judge whether Burnouf was appreciating Buddhism on its own merits or selectively amplifying the messages that appealed to him.

In Wagner's retelling, however, the anti-caste consciousness of the story completely disappears, and the central theme of his opera scenario becomes unrequited love. Several studies have illustrated how this Buddhist story reflects Wagner's personal love life, his reading of the European thinker Arthur Schopenhauer's pessimistic interpretation of Buddhism, and his encounter with Burnouf's Introduction and Buddhist studies in general.Footnote 26 These studies recount in detail how Wagner's encounter with this story was made possible by the colonial production of Buddhological knowledge, from manuscript discovery, collection, and circulation to scholarly summaries and editions, to philological analyses and academic publishing.

What this extant scholarship generally has overlooked is how Wagner reworked Buddhist karmic theory to suit his own views of responsibility and love. Avadāna, as a genre, explains how past actions (karma) lead to current events. In the premodern story, karma is used to explain how astrological knowledge and spiritual merits could bring desired outcomes and to redefine who counts as high or low caste. Moreover, the misfortune of this outcaste girl is simply attributed to attachment she formed during her past life as the wife of Ānanda.

Wagner rewrote the misfortune found in the ancient story as karmic retribution and reinterpreted karma as a mechanism of revenge. In Wagner's retelling, the outcaste girl committed a sin: In her past life, out of pride and arrogance (aus Stolz und Hochmut), she rejected the love of a young man. As punishment for her past sin, she was reborn as a Chandala girl who suffers the agony of hopeless love (die Qualen hoffnungsloser Liebe).Footnote 27 Wagner used his artistic license to rewrite the Brahminic caste hierarchy as an unethical internal psyche, one that is prideful and arrogant. He then attributed this inner psyche to this outcaste girl and thus fundamentally changed the moral message of the story.

Rather than serving as a platform for anti-caste consciousness, in Wagner's imagination, karma itself takes on a misogynist function: It warns prideful and arrogant maidens about the dire consequences of rejecting the romantic advances of men. While previous scholars have primarily interpreted this karmic function as Wagner's own psychological struggle with love and despair, I would suggest that a feminist critique helps illustrate the hidden social function of Wagner's play. In making this critique, I use Kate Manne's definition of misogyny: Misogyny is not a psychological attitude but the law-enforcement branch of a patriarchal order that targets girls or women for perceived or real violations of male-centered expectations.Footnote 28 In Wagner's mind, the unspoken male-centered expectation is that a young man's love should be reciprocated. If it is not, it must be the girl's fault: an unprovable psychological sin of pride and arrogance. Such a refusal to reciprocate is punishable by kind in later lives. Consequently, Wagner's new karmic retribution theory serves to instruct girls that if they do not accept love from young men, they will not only be deemed unethical but also suffer a similar fate in their future lives.

In short, Wagner's opera scenario reworks Buddhist karmic theory to fit a patriarchal social order in which girls and women are expected to care for and reciprocate the love of men. Like Burnouf, who singled out the anti-caste message that appealed to his European cultural sentiments, Wagner selectively amplified the universality of karmic theory to suit his own misogynist imagination. Both men used Buddhist social critique to confirm their own sensibilities and thus interwove this critique into existing systems of oppression, be it a civilizing mission or a patriarchal imagination. As I show in the next two sections, the Indian and Chinese authors also reimagined this romance to suit their own cultural sentiments. However, unlike Burnouf and Wagner, Tagore and Shang Xiaoyun retooled the ancient Buddhist universal quest for freedom and equality to challenge regimes of inequality: the caste system and patriarchy, respectively. Whether they achieved their goals of tangible social change is another story.

Chandalika, the Poona Act, and the birth of Buddhist social consciousness in India

In 1933, the renowned poet, the first Asian Nobel Laureate in Literature, Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), rewrote the ancient story into a play of two acts, Chandalika, to launch his social critique of the Indian caste system. The title Chandalika, with its feminine marker -ika, indicates that the protagonist is an outcaste woman. In this play, Tagore clearly makes the untouchable girl named Prakriti the heroine. Her chance encounter with Ānanda, an anti-caste hero himself who sees no reason why he cannot receive water from an untouchable, becomes the catalyst of her awakening to her universal humanity and a celebration of her dark skin, unsullied by the social construction of caste. She feels reborn and aspires to repay Ānanda's kindness by becoming his wife and serving him for the rest of her life. When Ānanda rejects her romantic advance, Prakriti persuades her mother to cast black magic to make Ānanda break his vow of celibacy. Eventually, Prakriti realizes her own mistake in forcing a monk to break his vow. When she begs her mother to break the black magic, her mother agrees to revoke the spell but dies from doing so. The play ends with Ānanda's paean to the Buddha's supreme power. Meanwhile, Prakriti's fate remains unknown.

Three essential features in Tagore's retelling warrant scholarly attention because they highlight a new formation of Buddhist social consciousness. First, Tagore rewrote the original debate about caste between the Buddha and the brahmin into an inner psychological journey of denial, struggle, and awakening experienced by the untouchable girl named Prakriti. In so doing, Tagore gave Indian untouchables a new subjectivity and a self-awareness of the oppression they were enduring. Both subjectivity and self-awareness were denied them in earlier versions of this story. Second, through Prakriti's psychological struggle, the ancient Buddhist soteriological goal of nirvāṇa as extinguishing suffering takes on two new meanings: unlearning the false self-identity inculcated by the Indian caste system and awakening to universal love. In this way, a new Buddhist social consciousness is born: Awakening to one's oppressed condition is key to achieving nirvāṇa. Third, Tagore ended the play with ambivalence: Only the high-caste Ānanda is saved by the supreme power of the Buddha; Prakriti's mother is beyond salvation, and Prakriti's own fate remains uncertain.

As I demonstrate in the following, when we contextualize these three features of Tagore's retelling within the politics of modern India and the colonial condition, it becomes clear that Tagore's rendition of Buddhist social consciousness can be seen as a socio-political commentary on Indian caste issues. However, in contrast to his countryman's Buddhist vision, that of the Dalit leader Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891–1956),Footnote 29 Tagore's commentary falls short of its transformative potential.

The most immediate context for appreciating Tagore's reformulation of Buddhist social consciousness is the 1932 Poona Act, an important landmark in understanding the complicated history of the caste system, the anti-caste struggle, and the emergence of the outcaste identity in India.Footnote 30 To make a convoluted story short, the Poona Act was a compromise made between the political leader of the Dalit (the untouchable or outcaste) community,Footnote 31 known as Ambedkar, and the civil activist and leader of the Indian Independence Movement, Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948). In the 1920s and 1930s, Ambedkar studied Buddhism seriously, but he had yet to perform the daring political act of leading the Dalit community to convert to Buddhism en masse (this would occur in 1956). As a political leader in the 1930s, inspired by the establishment of Muslims' separate electorates, Ambedkar fought for a separate electorate for the Dalit community.Footnote 32 However, Gandhi feared that a separate electorate for the Dalits would undermine the struggle for Indian independence and thus called upon Dalit subjects (Gandhi addressed them as “harijans,” children of god) to submit to the traditional Hindu ideal of functional solidarity.Footnote 33 Gandhi's defense of the Hindu subjugation of the Dalit community was diametrically opposed to Ambedkar's hope for the equal political rights of the Dalit people. The Poona Act that resulted from this clash was a form of affirmative action. Despite its failure to establish a separate electorate for the Dalit people, the Poona Act granted the Dalit community seventy-eight seats in the legislature and ensured the Dalits' right to select their own candidates and to participate in the general election. Even though Ambedkar failed to achieve his goals of socio-economic equality and political democracy, the struggle for a separate Dalit electorate nonetheless created a new Dalit political identity and subjectivity.

Viewed against this backdrop of the emerging Dalit political identity, the newfound subjectivity of Tagore's Prakriti can be interpreted as Tagore's commentary on the political controversy about the Dalits' rights in the emerging Indian nation-state. On the one hand, Tagore was sympathetic to the Dalit struggle for socio-political equality. At the opening of Act One, through the character of Prakriti, who has just gained a new birth (Bengali: natun janma) after hearing Ānanda's words, Tagore declares the caste moniker Chandala, which means “untouchable,” a false fiction (Bengali: mithyā kathā). In Prakriti's retelling of Ānanda's words, Chandala is merely a description of the dark clouds in the monsoon season. The blackness of the color does not change the clouds' birth/nature/caste (Bengali: jāta) as water. For audience members familiar with the political economy of the Indian caste system and the implications of the British census in solidifying the caste hierarchy in Indian society, Tagore's use of the Bengali word of jāta – replacing “jati” as an administrative idiom codified by British administrators – would have immediately registered as a comment on the intersection of British colonial rule, the pre-existing but fluid Indian conceptions of caste, and the quest for social equality launched by the Dalits.Footnote 34 By declaring that one's jāta has nothing to do with color and by likening jāta to the universal nature of water, Tagore affirms the universal humanity of the Dalit people and simultaneously rejects the concept of caste as a false fiction.

The loci of water and the well in this story further accentuate the modern relevance of the premodern anti-caste message when we take into consideration the 1927 Mahad Satyagraha (non-violent resistance; lit: holding onto truth) movement led by Ambedkar. On March 20, 1927, Ambedkar led a group of untouchables to use the water in a public tank in Mahad, a city in the state of Maharashtra. Traditionally, Dalits had been banned from using roads and bodies of water that were used by other Hindu castes. By 1924, the Mahad government had passed a resolution to give Dalit people the right to use public properties such as roads and water tanks built by the government. However, due to the protests launched by Mahad's high-caste individuals, the resolution was never implemented. The failed attempt to use political means to dismantle social inequality prompted Ambedkar's decision to lead the Mahad Satyagraha. This movement quickly led to many lawsuits. Both the legal battles and the social struggles lasted well into 1940 when Ambedkar declared March 20 as “Empowerment Day.” Today, March 20 is observed as Social Empowerment Day in India, but the Dalits' struggle to access water continues. Viewed in this light, Ānanda's ancient instructive lesson speaks directly to Indians' caste struggle: Water is water, no matter who touches it and who uses it. Like Prakriti, who realizes this simple truth and is reborn, the Dalits gained a new awareness of their own humanity in the wake of the Mahad Satyagraha.

When this new Dalit identity was born, the false self-identity inculcated by the Indian caste system was extinguished. Thus, in Tagore's retelling, the Buddhist goal of awakening (i.e., nirvāṇa as extinguishing suffering) takes on a social goal that is unlearning false social constructions. Tagore strengthens this social awareness through Prakriti's own voice and psychological transformation. According to Prakriti's retelling of her chance encounter with Ānanda at the well, Ānanda warned her not to humiliate herself as an untouchable and told her that self-humiliation (Bengali: ātmanindā) is a cardinal sin. Ānanda told Prakriti that the sin of self-humiliation is worse than suicide. For Prakriti, this warning becomes the catalyst for the death of her sense of Dalit inferiority and her rebirth as a human being.

In Tagore's modern rendition, Prakriti embodies the birth of a new Dalit social consciousness, a new quest for universal humanity, and a newfound self-confidence based on this quest for universal humanity. It seems that for Tagore, the realization of this universality is enough to overcome structural oppressions and to renew the egalitarian India preserved in the Buddhist tradition.

However, I argue that Tagore's anti-caste consciousness was limited by his imagination of a new India that was intimately connected to the Indian Buddhist revival and the Bengali Renaissance.Footnote 35 To a certain extent, both British archeological findings and the academic disciplines of Buddhology, philology, and Indology facilitated the increasing interest in Buddhism among the Indian educated elites. For many of these elites, Ashoka, the legendary Buddhist king, embodied the greatness of ancient Indian culture: a culture that had always been tolerant, adaptive, and open, and thus already modern.Footnote 36 Like many of his compatriots, Tagore valued Buddhism not because Buddhism cultivated a particular social consciousness but because Buddhism embodied the great values of the essential Indian culture and these great values, in turn, were the elements of universal humanity.

Tagore's understanding of Buddhism as a universal religion was intimately connected with British colonial knowledge production about Buddhism. Tagore first encountered the ancient story of Prakriti and Ānanda through his friend Rajendralal Mitra (1822–1891), whose position as the librarian-cum-assistant-secretary of the Asiatic Society allowed him access to many Buddhist manuscripts collected by colonial scholars. Mitra studied and then summarized many Sanskrit manuscripts of avadāna, including The Story of Śārdūlakarṇa, and published them in 1882.Footnote 37 Mitra is often lauded as the first modern Indologist of Indian origin, a historian, and a forebearer of the Bengali Renaissance.Footnote 38 As a philologist trained under the European education system, in his summary of this ancient romance, Mitra mirrored many of the choices made by Burnouf. These include an accurate recounting of the present story, the past story, and the moral message but the omission of all astrological knowledge that the king of the Chandala people employs to undermine the caste system and to prove his superiority.

Universal love is a common theme that is shared by Tagore and many Bengali Buddhist scholars. Tagore read Mitra's work extensively. Both Buddhism and the legendary Buddhist ruler Ashoka featured prominently in many of Tagore's literary masterpieces.Footnote 39 Similar to Mitra, Tagore was influenced by the colonial imagination of Buddhism as a universal and rational thought system and of Ashoka as a sage ruler. In a testament to Mitra's influence on his work, Tagore himself credited Mitra in the preface of the play Chandalika.Footnote 40

However, unlike Mitra, Tagore wielded his artistic license liberally in creating Chandalika and remade Prakriti's awakening as a psychological quest for universal love. Indeed, in Mitra's summary of the ancient story, Prakriti's love of Ānanda is attributed to his good looks, with which she is described as being “smitten.”Footnote 41 However, in Tagore's retelling, Prakriti's love for Ānanda is rewritten as motivated by devotion and the repayment of kindness because Ānanda awakened her to her own universal humanity and saved her from self-humiliation. In this sense, it is fair to say that Tagore's anti-caste consciousness hinged upon the hope that universal love alone could overcome the limitations of the world. In this sense, Chandalika embodies a new Buddhist social consciousness, where the ancient soteriological goal of nirvāṇa is imbued with a new meaning that is overcoming social injustice with universal love.

Nevertheless, the Buddhist social consciousness as embodied by Prakriti merely paid lip service to the equality of the Dalit people because it reduces a set of complex socio-politico-economic issues into a psychological awakening. In two key aspects, Tagore's reinvention of Buddhist social consciousness is similar to Gandhi's designation of the Dalits as harijans, a designation that affirms the Dalits' universal humanity in spiritual terms on the one hand yet subjugates the Dalits to the Hindu social hierarchy on the other hand. In the spiritual realm, Tagore granted the Chandalika universal humanity, which gave her a new birth. However, in this play, Tagore's vision was limited by his own ambivalence. In the play itself, Prakriti's mother's miserable death and Prakriti's ambiguous fate reveal to us Tagore's lack of trust in the Dalit people's capacity to become fully equal citizens of the great India. By reducing such a complex social issue to a matter of inner psychological struggle and proposing universal love as a panacea, Tagore's Prakriti failed to see that the political and social realities of inequality cannot be overcome by love alone.

Tagore's invocation of psychological awakening is in stark contrast with Ambedkar's political strategy. Ambedkar's strategy was to use the powerful state apparatus to give the Dalit people access to education, upward social mobility, and other necessary social conditions for their individual flourishing and collective well-being. Of course, there is nothing new about employing spiritual inclusiveness to justify regimes of inequality and to implement social control. Many Buddhist stories attest to the effectiveness of this spiritual strategy. Tagore's modern rendition of the Buddhist anti-caste consciousness merely represented a new iteration of this time-honored strategy.

What Tagore's Prakriti failed to realize is that universal love is what the ideology of caste precludes. Without socio-structural change, inner change does not matter. Twenty years later, when Ambedkar led the Dalit mass conversion to Buddhism in 1956, Ambedkar's new Buddhist social consciousness was supported by affirmative action in the constitution and a politico-social quest for structural compensation. Ambedkar's vision marked a new beginning for Buddhist social consciousness. Indeed, Surendran went as far as suggesting Ambedkar's Buddhism was a form of “liberation theology” that equated Buddhist spiritual equality with communist social equality.Footnote 42 While Ambedkar gave the Dalits a new socio-spiritual identity, Tagore offered the Dalits the opportunity to become more like the Bengali educated elite if only they were willing to have a change of heart. Instead of fighting against systemic oppression like Ambedkar, Tagore suggested that the Dalits should assimilate to the elite sensibility of affirming universal humanity and resisting materialism without offering any measurable social changes to achieve equity. In this sense, the Buddhist social consciousness embodied by Prakriti is akin to Anagārika Dharmapala's (1864–1933), who dreamed of a universal Buddhism grounded in an Indo-Aryan oneness. Instead of tearing down systemetic social oppressions such as race science, Dharmapāla envisioned an alternative hierarchy justified by a racial and spiritual superiority termed Aryaness.Footnote 43

In the end, although Tagore's retelling refashions nirvāṇa as extinguishing suffering into a social quest for overcoming the Indian caste system, it reproduces the dominant Brahminic ideology of the organic harmony of all castes by reducing the caste issue to a psychological and spiritual matter and thus lays the burden of liberation on the oppressed individuals. Once again, spiritual equality is used to provide psychological comfort to the Dalit people while keeping them in their “proper” place. Despite its lack of potential to lead to tangible social change, the Buddhist social consciousness in Chandalika merits scholarly attention. Unlike Wagner who appropriated Buddhist karmic theory to buttress his misogyny, Tagore gave new life to the ancient Buddhist anti-caste spirit. And yet, when compared with Ambedkar's Buddhist social consciousness, Prakrit's awakening looked pale: The former expanded the spiritual quest into the realm of concrete social reform, while the latter reduced a complex social issue to a spiritual awakening.

This contrast between Tagore's and Ambedkar's visions raises a crucial point about the different strategies that religious actors used to overcome structural inequality: The ancient soteriological toolbox could easily be adapted to either justify or tear down the status quo. Therefore, scholars should attend to both old doctrines and new contexts while examining power differentials with a discerning eye. This lesson is accentuated by another modern retelling of this love lore in a completely different context: twentieth-century Chinese cosmopolitan centers.

The Chinese Retelling of Modengjia nü: from a prostitute to the Buddhist ‘modern girl’

Unlike Wagner's and Tagore's retellings that emerged from contact with colonial Buddhological circles, the rebirth of this ancient story in modern China was the fruit of traditional Chinese Buddhist seeds nurtured by the emerging urban bourgeoisie desire, a direct outcome of the colonial economic domination of China.Footnote 44 Because Chinese urban-dwellers experienced colonial domination primarily through the influx of Western goods and Western ideas, the Chinese afterlife of the Buddhist past also took on a different meaning. As I show, the lasting popularity of Shang's 1920s Buddhism-inflected modern girl is underpinned by three skillful powerplays. First, the portrayal allayed Chinese patriarchal anxiety about unruly female sexuality and thus made the Western discourse of “free love” more palatable. Second, it unmasked the bourgeois consumerist pretense of “free love” as the only legitimate path to freedom and equality. Third, it exposed the falsity of the Western master narrative that suggests individual choice is the hallmark of modernity.

In modern China, the Buddhist past has long been taken to be part and parcel of Chinese culture. As is well known, since its entry into the Chinese land around the first century C. E., Buddhism had been absorbed into Chinese culture and changed the Chinese way of life through multiple processes that are typically subsumed under the label Sinification.Footnote 45 Consequently, throughout the transmission and transformation of Buddhism in China, this ancient story had been retold in multiple forms, all of which directly addressed local Chinese anxieties and aspirations.

Unsurprisingly, in the modern era, in contrast to Tagore's focus on the anti-caste critique, this ancient tale plucked a different tune. It played a crucial role in forming a different kind of Buddhist social consciousness that spoke directly to Chinese audiences in the urban centers who were overwhelmed by imported Western ideas, Western goods, and translations of Western literature. This new Buddhist social consciousness not only stemmed from a different textual lineage but also revealed deep-rooted patriarchal anxiety about women's sexuality stirred up by the modern quest for “free love” and individualism.Footnote 46 The Chinese retelling, The Mātaṅga Maiden (Ch: Modengjia nü 摩登伽女; Skt: Mātaṅgī),Footnote 47 was a modernist opera that debuted in 1927 in Peking. The opera gained traction and remained popular in major Chinese cities such as Shanghai, Tianjing, and Peking well into the 1940s.

The Mātaṅga Maiden became an immediate hit for its integration of traditional tunes with modern costumes and Western-style dance and music. This modernist opera earned the opera performer Shang Xiaoyun (1900–1976) a place in ‘the top five famous opera performers,’ wuda ming ling 五大名伶 in the Shuntian Times's (Ch: Shuntian shibao 順天時報) on July 23, 1927, and secured his prominence in the Republican Chinese opera scene. In contemporary China, many of Shang's fans still cherish this opera. Nevertheless, scholars of Chinese theatre have often dismissed it as one of many failed attempts to modernize Peking opera. Probably because Shang's new opera straddled the Western and the traditional, the religious and the secular realms, two of the naturalized binary categories in recent history, its role in bringing forth a new formation of Buddhist social consciousness remains unstudied to this day.

Before delving into the transmission history and providing a textual analysis of the play, I offer a sketch of Shang Xiaoyun and Qingyi jushi's artistic symbiosis that facilitates a well-rounded appreciation of their collaborative innovations. In many aspects, Shang's stardom as a Peking opera performer was made possible by Qingyi jushi's mastery of playwriting. Throughout his career, Qingyi jushi penned 21 plays for Shang. These plays not only celebrate Shang's dance, acrobatic, and fighting skills but also breathe into life a new type of female character who is both formidable warrior and moral paragon.Footnote 48 On the one hand, this type of female-warrior-cum-moral-paragon has a long history in Chinese culture. It is typically named nüxia 女俠 or xianü 俠女, where the concept of xia can be loosely rendered as the soul of martial art.Footnote 49 On the other hand, as a leading dramatist of modern China, Qingyi jushi argued that new plays should unleash the moral force of traditional Chinese performance art to transform modern society, adapt to modern sense and sensibility, and transform Chinese opera into an art form on par with Western performance art.Footnote 50 Consequently, Qingyi jushi's female characters served as a unique embodiment of modern women that appealed to a wide range of audiences in China's cosmopolitan centers.Footnote 51

In the rest of this section, I use Shang Xiaoyun and Qingyi jushi's co-creation of the figure Modengjia nü to showcase how certain Buddhist ideas – ideas that were at once “traditional” and “modern,” “Eastern” and “Western,” “conservative” and “radical,” “Buddhist” and “secular,” compel us to think beyond these putative binaries and instead look into genuine alternatives. First, I recount how the ancient Buddhist anti-caste consciousness was retooled as both a critique of Chinese patriarchy and a purification of Western “free love” into a quest for spiritual union. Then, I show step by step how in China, the Mātaṅga maiden, whose given name is Prakriti (Ch: Bojidi 缽吉帝) and whose family name is Mātaṅga (Ch: Modengjia 摩登伽), metamorphosizes into the very embodiment of a ‘modern girl’, modeng nü 摩登女 – one who dares to transgress the patriarchal norm that allows marriage only between families of equal social status (Ch: mendang hudui 門當戶對). Yet at the end of the play, the Mātaṅga maiden's pursuit of free love becomes purified as a quest for spiritual awakening. Consequently, in this modern Chinese retelling, the Buddhist soteriological goal functions as a tool to tame unruly Western free love and to soothe Chinese patriarchal anxiety.

To understand the merging of the Mātaṅga maiden (Ch: modengjia nü) with modeng nü, it is necessary to trace both the Sino-Japanese transliteration of ‘modern’ and the long Chinese transmission of ancient Buddhist love lore. The first one, the Sino-Japanese transliteration of “modern,” is relatively straightforward and has been well studied. In the late nineteenth century, there were quite a few Chinese translations of this term, mostly borrowed from either Japanese translation or the transliteration of English, French, and German words. By the early 1920s, modeng and xiandai 現代 were the most widely accepted translations. In particular, the term modeng was a Japanese transliteration of the French word “moderne,” whose Kanji characters are modeng 摩登.Footnote 52 These two Kanji characters coincidentally correspond to the first two Chinese characters of the transliteration of Mātaṅga as Modengjia 摩登伽. With knowledge of this coincidence of translation, one piece of the puzzle in Modengjia nü's metamorphosis into a modern girl falls into place.

Another crucial backdrop for appreciating the birth of the Mātaṅga maiden as a Buddhism-inflected modern girl (modeng nü 摩登女) is the contested discourse of “free love” (ziyou lianai 自由戀愛). Fueled by the iconoclastic spirit of young revolutionaries who pinned their hopes of freedom, equality, and social transformation on romance and love, the early 1920s became the heyday of free love. However, in the late 1920s and 1930s, free love came under attack from multiple directions. The progressives and the radicals criticized its bourgeois limitations. The conservatives and the nationalists criticized its erosion of social morality and the social institutions of family and marriage.Footnote 53 One apt example is Lu Xun 魯迅 (1881–1936), the father of modern Chinese literature, who questioned “love's pretense to realize individual autonomy and freedom as such – without a concomitant transformation of the socioeconomic system.”Footnote 54 Even the less radical but relatively progressive philosopher, a central figure in the movement of New Confucianism (Xin rujia 新儒家) and a leader in the China Democratic League (Zhonguo minzhu tongmeng 中國民主同盟), Zhang Dongsun 張東蓀 (1886–1973), blamed the modern discourse of free love and the atomized individual for fueling the fire of egoism and called for a transformation of love and passion for the common good (huayu zhuyi 化慾主義).Footnote 55 As I subsequently explain, the Buddhism-inflected modern girl rode with this tide of seeking alternatives to Western free love and individualism and thereby offered a powerful alternative that could balance sensual desires with moral demands.

To fully appreciate how this Buddhism-inflected modern girl brokered the seemingly conflicting demands of the traditional and the modern, one must look into the complicated transmission history of the Mātaṅga maiden. The complication arises from the fact that, since the introduction of Buddhism in China, the particular love lore not only had been translated, adapted, and incorporated into quite a few scriptures, Vinaya (monastic code) stories, and commentaries, but that since the sixteenth century, it had also been integrated into the broader Chinese culture as mediated by print culture and the rise of vernacular novels.Footnote 56 The Story of Śārdūlakarṇa was translated into Chinese at least four times between the second and the fourth centuries.Footnote 57 In these early translations, because China does not have the concept of caste (Skt: jāti), Mātaṅga 摩登伽 is interpreted as a ‘seed,’ zhong 種, without further explanation of what zhong means in its Indian context. However, these early translations have never been very influential outside of monastic-scholarly circles.

Instead, in premodern settings, this romance was mostly mediated through Vinaya and its commentaries and was widely referred to as “the story of Modengjia nü,” where the sense of zhong slowly shifted to denote family or clan. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the figure of Modengjia nü had penetrated literary circles more deeply thanks to the increasing popularity of an indigenous sutra, The Śūraṅgama Sūtra (Ch: Dafoding shoulengyan jing 大佛頂首楞嚴經; T945). To serve as the opening episode of this Chinese classic, the message of this ancient romance had to be repackaged to address a vexing issue facing male monastic practitioners: the need to keep one's vow of celibacy. Demeaning women thus became a discourse of ascetic misogyny. With the rise of vernacular novels, this fascinating drama caught the attention of many writers, and Modengjia nü quickly became a euphemism for prostitutes or licentious women with unruly sexuality.Footnote 58

Among the many intriguing twists and turns in these afterlives of Modengjia nü in premodern China are three themes that are essential to unpacking Shang's modern reinvention of the tale and its impact on the emergence of a new form of Buddhist social consciousness. The most prominent theme is the loss of the Indian meaning ascribed to the word ‘outcaste’ (Ch: jianzhong 賤種). Rather than signifying varṇa or jāti, in Buddhist commentaries and vernacular novels, “outcaste” is interpreted as a person in a contemptible profession, or modengjia, which served a euphemism for women who are reincarnated as prostitutes over many lifetimes (Ch: suwei yinnü 宿為淫女). This shift in the meaning of modengjia was primarily caused by The Śūraṅgama Sūtra and its commentaries that promoted ascetic misogyny.Footnote 59 The second theme is the interchangeable use of the terms modengjia and modeng to translate Mātaṅga throughout the translation history of this legend, with the former of the terms appearing somewhat more frequently.Footnote 60 By the sixteenth century, modengjia nü had become a euphemism for prostitutes, and modeng nü, the less-used term, came to have a similar meaning. The third theme is the stock use of the character Modengjia nü in early modern settings, whether Vinaya commentaries or vernacular novels. The character served as a prop to either showcase the supreme power of the Buddha or to prod male monastics to subdue their sexual desires.

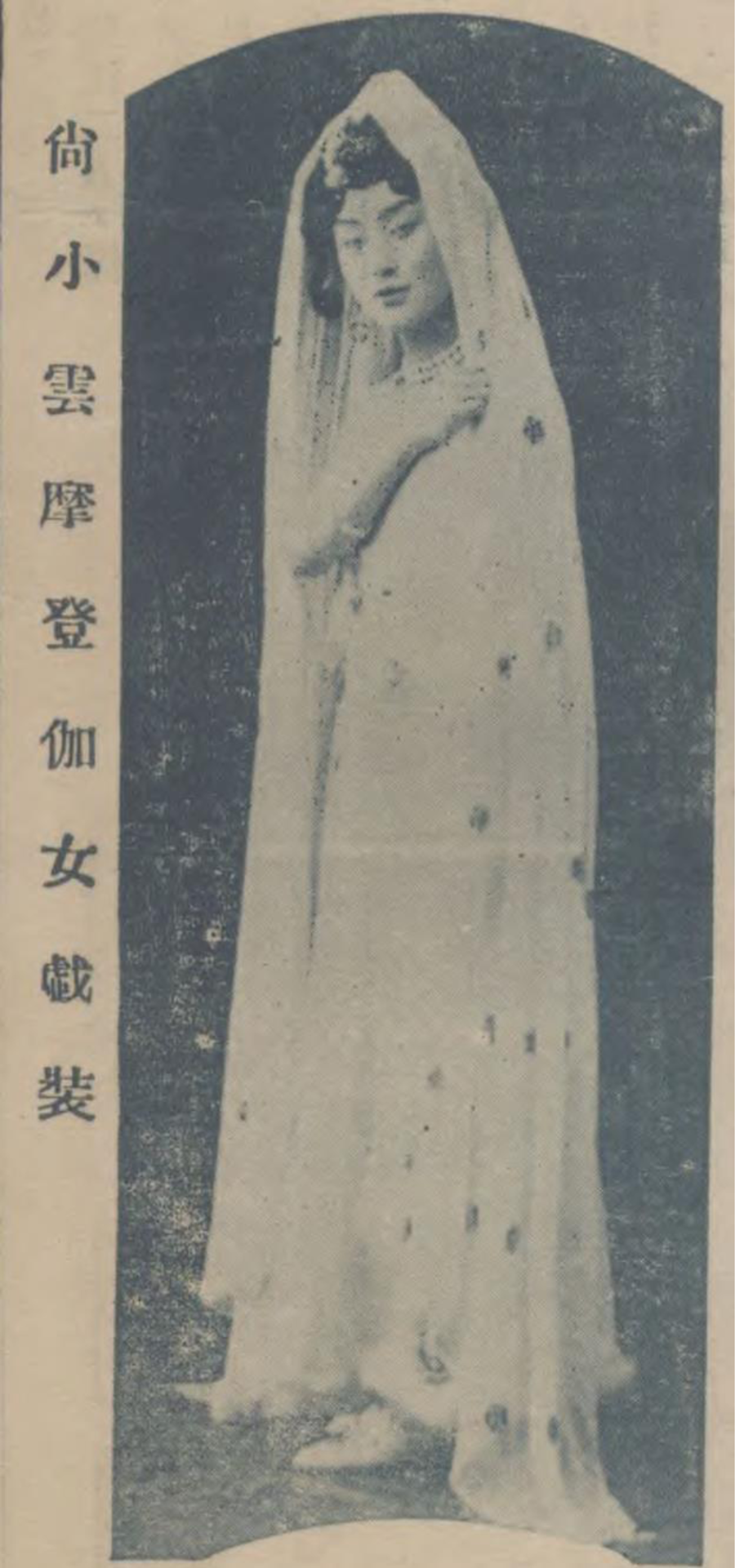

Despite recent Chinese scholarship examining the popularity of Shang's opera, the following questions remain unexplored: Why would a secular artist bring the Buddhist past to bear on an ostensibly new opera? What made it possible for Chinese audiences to welcome an opera adapted from an ancient Buddhist tale, whose central character was costumed in modern clothes and played by a ‘blue dress,’ qingyi 青衣 – a type of actor in the Peking opera who performed a female moral character – who swirled into the barn dance during the last scene accompanied by a violin and a piano playing British music (see Figs. 1 and 2)? Footnote 61

Figure 1. Still 1 (1929 Xijuyuekan).

Figure 2. Still 2 (1928 Hongmeigui huabao).

My central argument in this section is that Shang's play reflects a more widespread practice in the Republican cultural landscape: excavating Buddhist tropes to domesticate imported ideas and social norms, to stake out an intermediate position between total Westernization (quanpan xihua 全盤西化) and the school of national essence (guocui zhuyi 國粹主義), and to showcase the already-modern nature of Chinese culture. Broadly speaking, this modern afterlife of Modengjia nü reveals the rich dynamism of Chinese modernity. Theatrical innovations at the time thrived in the simultaneous encounter with both Western imports and the Buddhist past. This cultural crisscross facilitated the emergence of a new Buddhist social consciousness predicated on a spiritualized critique of both Chinese patriarchy and Western individualism.

In this following, I demonstrate how Shang's reinvention of Modengjia nü through music, dance, and costumes provided a vital visual trope for the Chinese audience to sublimate their anxieties about free love and the modern girl. As I demonstrate, the first two themes of modengjia nü and modeng nü as euphemisms for unruly women and prostitutes played a key role in repackaging premodern misogynistic discourses to soothe patriarchal ambivalence about the modern girl. The third theme of modeng nü as a prop served to showcase how Shang's theatrical innovation transformed this Buddhist figure into the embodiment of a modern girl, a protagonist who championed free love yet tamed the implications of unruly sexuality with Buddhist spirituality. My analyses of these three premodern themes reveal the missing pieces of the puzzle in understanding the birth of a new Buddhist social consciousness.

This historical metamorphosis of Modengjia nü into a modern girl happened in two steps: in Qingyi Jushi's rewriting and then in Shang's performance. First, the late Qing playwright Qingyi Jushi remade the Indian seductress into a Buddhism-inflected New Woman who dares to take charge of her own love life.Footnote 62 Second, Shang enacted Prakriti as a Modeng nü on stage, a girl who permed her hair, dressed in Western clothing exposing some of her body, kept her natural feet but put on sandals, and after her spiritual awakening, swirled into the barn dance accompanied by the violin (see Fig. 1).

Equally important, the success of Shang and Qingyi Jushi's cocreation benefited from the broader cultural emergence of new theatres and movies that reinterpreted Western values and practices using a Buddhist lens. Twentieth-century China experienced a “revolution of the heart” in which both cultural enlightenment and political revolution became cemented onto the quest of free love. Furthermore, emotion itself became a legitimate basis for a new social order.Footnote 63 In the eyes of many Chinese inhabitants of cosmopolitan centers like Shanghai and Peking, this sea change in values and moral norms was underscored by a tsunami of newspapers, magazines, newfangled theatres, movies, nude painting, jazz, dancing halls, and popular songs. Uprooted from the Confucian moral system, floating in the sea of new media, and bombarded daily with messages about free love and individual liberty, many found this new world disorienting. To help the Chinese make sense of these drastic cultural changes, in the 1920s and 1930s, a niche market of Buddhist-themed movies and theatres quickly grew up. This market was often termed zongjiao xi/pian 宗教戲/片, ‘religious play/movie,’ or more derogatorily, shengguai xi/pian 神怪戲/片, ‘play/movie of spirits and monsters.’ Although religious theatrical performances in this era are still understudied, a brief examination of this new genre demonstrates that many movies were based on Buddhist stories related to the goddess of compassion, Guanyin 觀音; the Living Buddha, Jigong 濟公活佛; and the funeral performance of ‘Maudgalyāyana Saving his Mother,’ Mulian jiumu 目連救母.Footnote 64 Qingyi Jushi's retelling reflected a much broader cultural trend in the Republican era that reworked Buddhist themes to indigenize Western values. Indeed, Modengjia nü became a Buddhism-inflected modern girl whose Buddhist spirituality provided an anchor for the audience to reimagine individual freedom without having to uncritically accept sensual pleasure.

In essence, this Buddhism-inflected modern femininity both affirmed the human desire for dignity and individuality and undermined the power of free love and emotion to establish new moral norms by taming these desires with a soteriological awakening. To understand this new formation of Buddhist femininity, we need to examine Qingyi Jushi's plot and its deviation from premodern retellings.Footnote 65

Four elements of Qingyi Jushi's retelling warrant particular scholarly attention. First of all, Prakriti is the protagonist, while Ānanda and the Buddha only play supporting roles. Second, Prakriti is portrayed consistently as the one who actively pursues love. In the scene during which Ānanda asks for water, Prakriti, shocked by Ānanda's rejection of caste discrimination, which would have required that she keep her love for Ānanda a secret, boldly expresses her love and admiration for him. Close to the end of the play, after Ānanda is saved by the supernatural power of the Buddha and bodhisattva Mañjuśrī, Prakriti chases Ānanda to the Saṅgha and entreats the Buddha to grant her wish to be with Ānanda forever. Third, Prakriti's spiritual awakening is depicted in detail. In the final scene, in contrast to premodern retellings' cursory treatment of Prakriti's enlightenment, Qingyi Jushi explicitly uses the foulness of Ānanda's body and the impermanence of sensual love as triggers for Prakriti's liberation. Last but not least, after Prakriti lets go of her sexual desires, she dances for the Buddha to thank him for ordaining her into a spiritual community.

These four differences are the primary sites of Qingyi Jushi's artistic intervention. By relegating Ānanda to a supporting role, Qingyi Jushi puts Prakriti's humanity and subjectivity at center stage, echoing the inchoate themes of feminist liberation. This feminist theme of affirming women's humanity and subjectivity is accentuated by the second site of intervention. When Prakriti hesitates to give Ānanda water because of her low social status as a Chandala, Ānanda simply answers, “I asked for water. Whether you are a Chandala or not is not relevant.” Upon hearing this, Prakriti realizes that Buddhists treat all human being as equals and do not discriminate against the Chandalas. She then boldly expresses her admiration and love for Ānanda and asks for his hand in marriage.Footnote 66 It is important to note that in this Chinese retelling, Modengjia is domesticated as a family name, shared by both Prakriti – most frequently addressed by her last name as Modengjia nü (lit: the maiden whose last name is Modengjia) and her mother – Mrs. Modeng (Modeng furen 摩登夫人). In this sense, although Prakriti embodies a modern feminist awakening of free love, she and her mother remain within the patriarchal power structures that label women as property of their family. Thanks to the long process of Sinification that was taking place at the time of Qingyi Jushi's retelling, the Indian caste consciousness of the tale was lost entirely. Instead, the tale's anti-caste spirit was repackaged as both the pursuit of individual freedom and love grounded in equal humanity and a critique of patriarchy.

Modengjia nü's boldness in expressing her love is the main site for her transition into a modern girl (modeng nü) because the modern girl in Republican China was marked by her active pursuit of love. This active pursuit of love may have been too much for Chinese patriarchal sensibilities, which considered humility and deference to be womanly virtues and robbed even female fertility goddesses such as the White-Robed Guanyin of their sexuality. While the increasing popularity of Modeng nü might have stirred up Chinese patriarchal anxiety about female sexuality, Prakriti's low social status and the domestication of Mātaṅga as a marker for prostitution served to ameliorate this anxiety: After all, for a girl who was born into a family of prostitutes, taking an active role in love seems expected rather than transgressive. Taking advantage of this cultural stereotype, Qingyi Jushi was able to safely refashion Prakriti's boldness as a virtue. In earlier scenes, Qingyi Jushi purposefully highlights Prakriti's self-respect and her refusal to join the traditional family trade of seducing rich young men.Footnote 67 This depiction is in stark contrast to the Buddhist scriptural depiction of her as burning with sexual desire. Instead, at the well, when Prakriti first meets Ānanda, Qingyi Jushi indicates that Prakriti's love springs from her spiritual affinity with Ānanda and her conviction that her virtuous lifestyle thus far makes her a worthy partner of this respectable and handsome monk.Footnote 68 Close to the end, after her spell is broken by the Buddha's power, Prakriti begs the Buddha to affirm her union with Ānanda and promises to practice Buddhism as a laywoman.Footnote 69 Throughout this opera, the appeal of Buddhism as an egalitarian ideology consistently functions as a justification for Prakriti's pursuit of love despite her social status. In this sense, in Qingyi Jushi's retelling, the ancient Buddhist anti-caste consciousness metamorphosizes into a powerful tool to dismantle the patriarchal custom of marriage between two individuals of equal social status. Simultaneously, it offers a different kind of love grounded in the Buddhist egalitarian ideal.

However, it would be a mistake to read Qingyi Jushi's retelling as advancing a bourgeois feminist agenda sanctifying individual choice. The third difference, found in Qingyi Jushi's depiction of Prakriti's spiritual awakening, reveals to us that ancient Buddhist spiritual exercises were employed by the playwright to curtail female sexuality and thus tame the Western style of free love and individual choice so that it fit with Chinese patriarchal sensibilities. Right after Prakriti appeals to the Buddha to allow her union with Ānanda, the Buddha uses his supernormal power to show Prakriti the aging Ānanda and the skeleton of his dead body. This meditation on the foulness of Ānanda's body extinguishes Prakriti's burning desire and leads her to realize the foundational Buddhist doctrine of impermanence. Awakened by the direct experience of impermanence, she decides to join a monastic order just like Ānanda. In so doing, she not only purifies her sensual desire into a spiritual quest but also redefines free love as spiritual union.

Despite its taming of Western free love and lack of feminist consciousness, Qingyi Jushi's retelling, and in particular its drawing on the foulness of the body, brought forth a new formation of Buddhist social consciousness because it fundamentally reverted the male gaze common to traditional Buddhist practices. As is well known, in Indian Buddhist narratives, the foulness of the body commonly appears as the corporal decay of women's bodies for the edification of monks.Footnote 70 In contrast, Qingyi Jushi uses Ānanda's aging body and skeleton as heuristic tools to assist in the formation of Prakriti's spiritual subjectivity. Together with this dramatic reversal of the male gaze, a new form of Buddhist social consciousness is born.

However, this new Buddhist social consciousness remains ambiguous because it must negotiate two competing kinds of the male gaze. On the one hand, the Chinese patriarchal gaze sought to control female fertility while erasing public display of female sexuality. On the other hand, Western free love came together with the capitalist commodification of female bodies for male bourgeoisie consumption and thus promoted women's public displays of sexuality.Footnote 71 When Prakriti decides to become a nun, the traditional trope of “taking refuge in the Saṅgha” is reborn as a path out of the penetrating gazes of both patriarchy and bourgeoisie consumerism. I argue that the brilliance of this ending lies in its rejection of both kinds of the male gaze, and in turn, its powerful exposure of the empty promises made by both systems of oppression.

Modengjia nü's dramatic metamorphosis into Miss Modern/Modeng could not have happened without Qingyi Jushi's fourth intervention. The fourth difference, which is represented by Qingyi Jushi's portrayal of Modengjia nü swirling into the barn dance accompanied by the violin, opened up possibilities for Shang's theatrical innovations.Footnote 72 While it is common in Buddhist tradition to see heavenly maidens dancing for the Buddha as a form of dāna (donation as a way to accumulate spiritual merits), Prakriti's barn dance proves crucial to the birth of the Buddhism-inflected modern girl. The barn dance was a popular genre in the dancing halls of cosmopolitan Chinese centers, and images of dancing girls often overlapped with those of prostitutes in twentieth-century Shanghai.Footnote 73 Yet Prakriti's decision to offer her dance of thanksgiving to the Buddha not only affirms her as bold and active but also purifies the seductive dance itself into a spiritual exercise. As such, Prakriti, the dancing girl, is reborn as a Buddhist modern girl who asserts her individuality but transcends her worldly desires (see Figs. 2 and 3).Footnote 74

Figure 3. Still 3 (1934 Xiju yu dianying).

When Shang enacted this Buddhism-inflected Modeng girl on stage, he provided Chinese audiences with a visual repertoire with which to imagine a modern girl. Shang's theatrical innovations were rooted in conscious and attentive cultural re-mixing on multiple levels. To sculpt this image of a Buddhist modern girl, Shang relied on costumes that seamlessly integrated cultural memories of traditional beauties, saintly figures, and the modern girl. In Figure 1, one of the frequently reproduced stills from Shang's performance, the girl's shoes closely resemble the embroidered shoes made for natural feet (Ch: fangjiao xie 放腳鞋), signaling her progressive leaning. The fur trim and gold embroidery of the girl's long skirt readily remind audience members of the luxury lifestyle of the dancing girl. The close-fitted waist, the short sleeves, and the low cut of the dress invoke the visual imagination of a modern girl. Yet the girl's long hair is tied up into a retro style. Her double-layer pearl necklace signifies feminine beauty, purity, and the preciousness of her innate humanity. In another still, Shang, as Prakriti, is seen wearing an embroidered chiffon shawl on top of this modern dress, evoking the image of a traditional beauty or White-robed Guanyin (Fig. 4).Footnote 75 In contrast, in her dancing scene, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, Prakriti is wearing sandals that reveal most of her feet and a shorter dress that is decorated with a lot of fur trim. The pearl necklace remains, but her hair is now permed with curls that bring to mind both the Buddha's topknot and a modern girl's permed hair. Shang's theatrical innovations in both dance and costumes thus signaled Modengjia nü's full metamorphosis into Miss Modeng (Ch: modeng xiaojie 摩登小姐).

Figure 4. Still 4 (1928 Shijie huabao).

In sum, the playwright Qingyi Jushi and the Peking opera performer Shang Xiaoyun worked in tandem to bring to life a Buddhist modern girl, Prakriti. She not only bravely pursued free love, thus embodying the modern ethos of individualism and gender equality, but also transformed her sensual desire into a spiritual quest, thus allaying patriarchal anxiety about unruly female sexuality and denying the liberatory potential of Western individualism. On the one hand, the Buddhist quest for spiritual liberty functioned to both tame the transgressive power of the modern girl in tearing down the Chinese patriarchal value system and reject the bourgeois consumerist presentation of free love and individual choice as the only viable path toward equality and liberty. On the other hand, this distant past functioned as a generative force to free the girl's imagination and artistic expression and offered the audience a Chinese modern woman outside of Western individualism. While in premodern China, Sinification had made Buddhism an indigenous culture, in modern times, this indigenized Buddhist universal spirituality proved a powerful platform to absorb Western values into the existing Chinese ethos and thus allow Chinese performers and audiences to imagine a Chinese culture that was already modern.

Admittedly, contemporary readers would have hardly found Modengjai nü's choice a satisfactory solution to the problem of gender inequality. However, the goal of this study is not to offer a solution to a social problem but to explain why and how this outcaste prostitute enthralled a wide range of Chinese audiences in cosmopolitan centers. The central argument of this section is that the outcome of this Buddhist encounter with Western free love was a new formation of Buddhist social consciousness, one that repackaged Buddhist spiritual equality as a critique of both patriarchal constraints and unruly individualism.

The promises and limits of cultural comparisons

The current study has examined how the Buddhist seeds of equality and liberty blossomed into tools for imagining a more egalitarian society. The findings reveal both the promises and limits of cultural comparisons. Cultural comparisons open up new ways of identifying strategies and tactics in overcoming colonial domination outside of the two poles of coercive political power and the inescapable economic imperative.

The current comparison of two theatrical afterlives of a Buddhist romance in India and China reveals a shared socio-spiritual horizon that sought to nurture the dormant Buddhist seed of spiritual inclusiveness to establish new, more equitable socio-moral norms. Consequently, two new formations of Buddhist social consciousness emerged. Buddhist spirituality was central to cultural imaginings of an equitable global order in both India and China. It thus exposed the limitations of “rational China” and “spiritual India,” images that had resulted from comparative studies based on political regimes: namely, Indian democracy and Chinese socialism. Joining forces with recent methodological reflections on China–India studies and Hansen Sen's suggestions to go beyond “the geopolitical framework,”Footnote 76 the current study demonstrates the importance of examining the cultural history of modernity through the lens of modern afterlives of the Buddhist past. Historically, Buddhism has devised many skillful practices to ameliorate worldly suffering and offered many perspectives on spiritual equality. Tagore's and Qingyi Jushi's retellings reveal a critical stage in the formation of alternative visions of social justice based on Buddhist spirituality. They also uncloak a much broader trend of improvising the Buddhist past for theorizing social consciousness that defies neat binaries of the traditional and the modern, the conservative and the progressive, the partriarchal and the feminist. In their acts of weaving together whatever threads available at hand and in their commitments to telling a different story of becoming modern, scholars identify artistic vitalities of undercutting the single story of Western modernity and Eastern response that had been propagated for too long.

Another promise of studying the cultural history of modernity in India and China lies in its potential for the scholars educated within the disciplinary structures set up by colonialism to break free from the legacy of Eurocentrism. The vital productive power of Eurocentrism lies not in the fact that scholars are fixated on things Western. As many scholars have incisively argued, Eurocentrism keeps reproducing itself thanks to an unreflective use of the binaristic paradigm that equates the West with the universal and the East with the local or the particular. As such, what is at stake is not merely a balance of scholarly attention to Western and Eastern sources but the very claim to universalism grounded in moral sources in the Global South.

As my analysis has demonstrated, in contrast to Wagner, who appropriated the universal Buddhist karmic theory to shore up the persuasive power of his misogynist ideas, both Tagore and Shang nutured the Buddhist seeds of anti-caste consciousness to reclaim the narrative of who is universal and modern. Looking through the eyes of these artists situated on the receiving end of the colonial oppression raises pressing and heretofore unexamined questions related to alternative visions of global modernity: What attracted historical actors in China and India to the Buddhist past in this modern era? What were their visions of global modernity as encoded in their reinventions of this Buddhist love lore? Why and how did the Buddhist egalitarian spiritual message find global resonance in an era of globalized inequality?

However, cultural comparisons are also limited by source materials. In modern theatre and literature, psychology and subjectivity are the prevailing winds. Therefore, it is not surprising that all three modern authors amplified the psychological aspects of the Buddhist past, even as they used the inner psyche as a site to voice their discontent with perceived or real unjust social norms. In particular, Tagore's retelling reduces a complex social issue into a psychological awakening and thus significantly impairs the power of Buddhist spirituality as a social critique. Qingyi Jushi's retelling tames the feminist quest for free love with Buddhist soteriological and psychological exercises. In order to dismantle existing regimes of inequality, both authors used Buddhist psycho-spirituality as a panacea for complex social issues. Consequently, they undermined the persuasive power of their respective articulations of social consciousness and reproduced colonial epistemic domination by reducing systemic oppressions into a matter of individual psychological struggle.

Ultimately, to gain a well-rounded picture of this Buddhist socio-spiritual horizon, its complicated origins, uneven developments, and broader impact, scholars need to look for different kinds of evidence. Cultural comparisons complement political and economic histories by uncovering overlooked techniques of storytelling that have been used in an attempt to change social norms. Such comparisons thereby offer a different window by which to appreciate the fears and aspirations of historical actors themselves.