To the Editor—Central-line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) remain a significant problem for hospitalized children, particularly among hematology-oncology populations. Recognizing the unique challenges posed by neutropenia and impaired gut integrity, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Healthcare Safety Network introduced a revised surveillance protocol for CLABSIs in January 2013 that included a new classification for mucosal-barrier injury (MBI) laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infection. 1 – Reference See, Iwamoto, Allen-Bridson, Horan, Magill and Thompson 4 Many hypothesize that MBI CLABSIs are related to translocation of enteric microorganisms across a disrupted intestinal epithelium, suggesting that bundles focused on catheter insertion and maintenance would not impact infection rates.Reference Epstein, See, Edwards, Magill and Thompson 3 , Reference Metzger, Rucker and Callaghan 5 Through a retrospective, stratified analysis of in-house data, we describe changes in MBI and non-MBI CLABSIs in oncology patients at our institution.

METHODS

Study Design

A retrospective observational study was performed, comparing the monthly rate of MBI and non-MBI CLABSIs (per 1,000 central-line days) among oncology inpatients at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia from January 2013 to March 2016. This study utilized existing data reviewed for quality improvement purposes; therefore, it was deemed exempt from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board oversight.

Study Setting

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is a 546-bed quaternary-care pediatric hospital, which has 50 oncology and bone marrow transplant (BMT) beds and an average of 1,557 oncology admissions per year. The Department of Infection Prevention and Control includes 8 certified infection preventionists and a full-time medical director.

At the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, CLABSI prevention efforts are ongoing and have been conducted for many years. As such, pre-existing standard catheter insertion and maintenance bundles, based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines and in line with recommendations by the Solutions for Patient Safety Collaborative, underwent serial Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles to optimize the adoption of bundle elements. No new interventions were introduced.

Data Sources and Definitions

Data on CLABSIs and CLABSI rates were obtained by the Department of Infection Prevention and Control. The department conducts active surveillance, including review of microbiology laboratory results and the electronic medical record to identify CLABSIs in all inpatient units. Infections meeting the National Healthcare Safety Network definitions for MBI and non-MBI CLABSI were included in the study. 2

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilized to characterize oncology and BMT patients with CLABSIs, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, median, and interquartile range for continuous variables. To assess the longitudinal trends, a single Poisson regression model of monthly rates of MBI and non-MBI CLABSIs per 1,000 central-line days was fit with time as an independent variable. For these analyses, we used Stata version 14.2 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

During the study period, 114 CLABSIs were identified in 88 oncology (77%) and 26 BMT (23%) patients. Median age was 8 years (IQR, 3–16 years); 53 of 114 (46%) of patients were White and 25 of 114 (22%) were Black. The most common underlying diagnoses were acute myeloid leukemia (n=42, 39%), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=24, 22%), and history of BMT (n=24, 22%). Total catheter utilization for the study period was 857 per 1,000 patient days.

Of the 114 CLABSIs identified, 68 (60%) met MBI criteria, including 57 (84%) among oncology and 11 (16%) among BMT patients. The proportion of CLABSIs meeting MBI criteria was more common in oncology patients ( n=57 of 88, 65%) than BMT patients (n=11 of 26, 42%) (P=.02). Escherichia coli, Streptococcus mitis, Enterobacter cloacae complex and Klebsiella pneumoniae were the most common pathogens isolated among all MBI CLABSIs as well as among MBI CLABSIs identified in oncology patients. Among MBI CLABSIs identified in BMT patients, the most common isolates were K. pneumoniae and S. mitis.

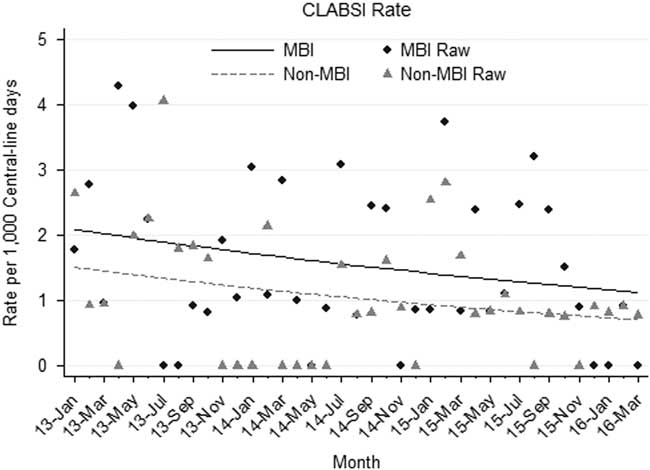

The median monthly rate of CLABSIs in oncology and BMT patients over the study period was 2.52 (IQR, 1.03–3.38) per 1,000 central-line days. Stratifying by MBI versus non-MBI CLABSIs, median monthly rates were 1.03 per 1,000 central-line days (IQR, 0.84–2.44) and 0.84 per 1,000 central-line days (IQR, 0–1.68), respectively. Similar rates were observed within both subpopulations of oncology and BMT patients. A nonsignificant downward trend was observed in both MBI and non-MBI CLABSIs over the study period (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in the rate of change between MBI and non-MBI infections (P=.873) during the study period.

FIGURE 1 Mucosal barrier injury (MBI) versus non-MBI central-line–associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) rates, January 2013 through March 2016.

DISCUSSION

Following efforts to improve central-line care bundles, prior reports separating CLABSI data by MBI vs non-MBI identified disparate trends in rates.Reference Epstein, See, Edwards, Magill and Thompson 3 , Reference Metzger, Rucker and Callaghan 5 Researchers concluded that standard CLABSI bundles were insufficient to impact MBI rates.Reference Metzger, Rucker and Callaghan 5 However, we observed a similar rate of change in our MBI and non-MBI CLABSIs in a period of ongoing efforts to prevent CLABSIs in this population.

The use of surveillance definitions subject to change is a potential limitation in our study. Since its inception, the MBI definition underwent a single modification in 2014, wherein the neutropenia screening window was increased from 4 days (day of positive culture plus the 3 preceding days) to 7 (day of positive culture plus the 3 preceding days and the 3 days following the culture). Broadening the eligibility window for neutropenia could potentially increase the number of infections that met criteria for MBI CLABSI; however, this should not impact the comparison of the rate of change between MBI and non-MBI CLABSIs.

Our data suggest that standard CLABSI prevention practices are likely to prevent both MBI and non-MBI CLABSIs. Our findings further indicate that the pathogenesis of some MBI CLABSI events might be related to breaches in the insertion and care of catheters. While novel efforts to prevent MBIs are needed, strategies should not preclude application of standard bundle practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support: This research was supported in part by a CDC Cooperative Agreement (FOA#CK11-001) with the Epicenters for the Prevention of Healthcare Associated Infections. A.M.V. received grant support from a National Institute of Health T32 institutional training grant.

Potential conflicts of interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.