To the Editor—Since monkeypox was first identified in humans in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970, most human monkeypox cases have been reported in Central and West Africa, with the largest documented outbreak occurring in Nigeria in 2017.Reference Ogoina, Izibewule and Ogunleye1 Monkeypox, a rare viral zoonotic re-emerging disease caused by an orthopoxvirus, has similar clinical signs and symptoms as smallpox and a case-fatality rate of 11% in unvaccinated patients.Reference Ježek, Szczeniowski, Paluku and Mutombo2 It can be transmitted from person to person via direct contact with infected lesions, through respiratory secretions, or from contaminated objects and environments. Risk of infection for healthcare workers (HCWs) are high,Reference Petersen, Kabamba and McCollum3 and patient-to-HCW transmission of monkeypox has been reported in the Central African Republic and the United Kingdom, where staff used inadequate standard contact precautions.Reference Nakoune, Lampaert and Ndjapou4-Reference Senthilingam6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended standard and contact precautions for the management of human monkeypox.7

Singapore, an island city-state in Southeast Asia, is a major travel hub that received >5,000 visitors from Africa between January and May 2019.8 On May 8, 2019, the human monkeypox case was confirmed in Singapore in a 38-year-old Nigerian man who arrived in Singapore on April 28, 2019, to attend a workshop. Before his travel to Singapore, he had resided and worked in the Delta state in Nigeria and had attended a wedding on April 21 in a village in Ebonyi State, Nigeria, where he consumed bushmeat.9 He presented to the emergency department of Tan Tock Seng Hospital on May 7 with fever, muscle aches, and vesicular skin lesions. Due to his travel history, he was transferred from the ambulance directly to a negative air pressure (NEP) isolation room at the emergency department. After staying for 5 hours at the emergency department, he was admitted into an NEP in an isolation unit at the adjoining National Centre for Infectious Diseases for further clinical management on the same day, and laboratory confirmed as monkeypox infection the next day (May 8).

Contact tracing operations were carried out at the hospital to identify HCWs who were in contact with the patient before admission to the isolation unit. All staff identified as close contacts were assessed for types of personal protective equipment (PPE) used. Laboratory staff who processed the patient’s specimens on an open bench (ie, outside a biosafety cabinet) were also considered as having close contact and assessed. Each HCW identified as having possible exposure was contacted via phone call and interviewed by a designated staff to verify the type of contact with the patient and the PPE used.

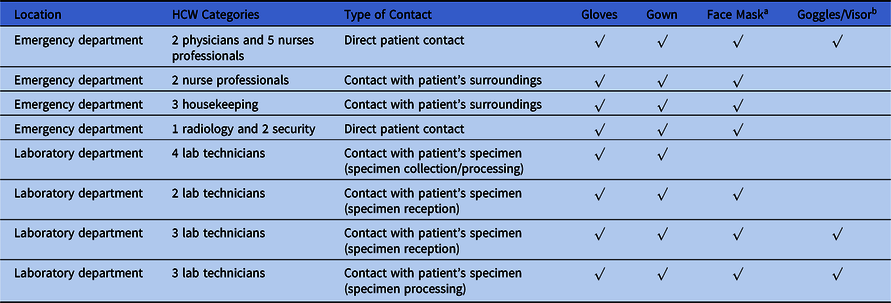

Following individual risk assessments, 27 HCWs were identified to have had close contact. Of these, 12 HCWs had had direct contact with the patient himself or the patient’s surrounding (defined as within 2 m of the patient) at the emergency department, 3 HCWs had handled the patient’s linen and cleaned the NEP room in the emergency department, and 12 were laboratory staff who had handled the patient’s specimens. All had protected exposure to the patient, with the appropriate and adequate use of PPE (Table 1).

Table 1. Categories of Healthcare Workers (HCWs) by Location, Type of Contact, and Type of Personal Protective Equipment

a N95 respirator for respiratory protection.

b Eye protection.

A designated group of public-health–trained staff implemented follow-up phone surveillance on all staff contacts. Phone calls were made to all nonphysician HCW contacts every other day from the day 1 to day 21 postexposure to monitor their health status. After the initial phone call, the 2 physicians were advised to monitor their own health. Symptoms monitored included fever, swollen lymph nodes, skin rash, headache, and myalgia. All exposed HCWs were also given the phone numbers of the surveillance team for immediate contact if they felt acutely ill. Unwell HCWs were immediately referred to the dedicated infectious disease clinic with appropriate precautions in place for review at the earliest available time. Because the risk of exposure was ascertained to be low for all staff contacts, they were allowed to continue with their routine activities during the surveillance period.

During the follow-up period of 21 days, 2 nursing staff reported respiratory symptoms. They were reviewed by infectious disease physicians and were clinically diagnosed with viral upper respiratory infections. They were treated symptomatically, were given medical leave to rest, and recovered uneventfully. At the end of the surveillance period, none of the 27 HCWs developed symptoms suggestive of monkeypox infection.

We have comprehensively and systematically documented the contact tracing processes and active surveillance activities in a tertiary-care hospital in response to a human monkeypox case importation. A well-developed protocol that enables the early detection of suspected cases of emerging infectious diseases ensured that patients are managed in appropriate isolation room facilities in the emergency department from the outset; this would greatly minimize exposure in a crowded emergency department. Furthermore, clear infection prevention guidelines on the appropriate PPE for different HCWs, based on patient care activities and the transmission risk, are crucial. All HCWs who had attended to the patient had complied with the hospital’s infection prevention guidelines. Finally, although the risk of transmission of monkeypox to the HCWs was deemed to be extremely low, we took additional measures to actively follow up on each HCW contact to provide assurance and health education to anxious staff who did not have a good understanding of monkeypox. Early detection of symptoms in close contacts through active phone surveillance may facilitate prompt medical review and diagnosis of new infections to prevent further transmission.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge all staff involved in contact tracing operations at the hospital.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.