To the Editor—Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) are an increasing problem worldwide.Reference Nordmann, Naas and Poirel 1 Because they are often resistant to almost all available antibiotics, treating infections caused by these bacteria is extremely difficult. Recently, concern has also been raised about hospital sewage as a potential source of CPE in the environment.Reference Picão, Cardoso and Campana 2 To investigate this possibility locally, we recently sampled sewage from 6 hospitals and a community institution (used as control) in Singapore.

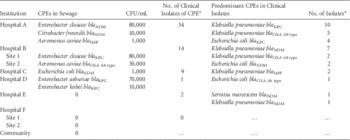

Unconcentrated sewage was streaked out using 1 µL and 10 µL loops onto ChromID CARBA plates (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). After incubation for up to 48 hours at 35°C in air, 3 predominant colony morphotypes resembling Enterobacteriaceae per sample were chosen for further investigation. Carbapenemase activity was determined by the Carba NP test and the modified Hodge test.Reference Nordmann, Poirel and Dortet 3 , 4 Identification of bacteria was done by MALDI-TOF (Bruker Daltonics Pte. Ltd., Singapore). The presence of carbapenemase genes was confirmed by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR).Reference Poirel, Walsh, Cuvillier and Nordmann 5 The results of our survey are shown in Table 1 together with the number of CPEs isolated from clinical specimens (not stool surveillance cultures) taken from patients in each hospital.

Table 1 Characteristics of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterbacteriaceae (CPE) in Sewage and Clinical Samples

a January 1, 2014–May 31, 2014.

CPEs were found in the sewage of 4 hospitals. The numbers of isolates of CPE in sewage generally corresponded with the frequency of isolation of clinical isolates in the hospitals. However, there was no direct correlation between sewage and clinical isolates with regard to bacterial species and carbapenemase genes. Clinical isolates were commonly Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli, whereas Enterobacter and Aeromonas species were more common in sewage. We are uncertain of the reasons for this discrepancy between sewage and clinical isolates; it could be a chance finding resulting from limited sampling. However, this finding does seem to be quite consistent across different hospitals. Another possibility is that it may reflect a difference between the species of CPE that cause disease (clinical isolates) and those that merely colonize the gut (found in sewage) without resulting in infection. This explanation is only partial. During the same period (January 1, 2014–May 31, 2014) in Hospital A, which has the most comprehensive surveillance program for CPE, K. pneumoniae (83 isolates) and E. coli (47 isolates) remained the most common species isolated from patient stools, with Enterobacter cloacae a distant third (27 isolates). No Aeromonas species were isolated from stool surveillance cultures. Finally, these results may be the result of an ecological dynamic occurring in the sewage system. Aeromonas species are able to survive and proliferate in water distribution systems and may acquire plasmids containing carbapenemase genes from the clinical isolates entering into the system.Reference Borrell, Figueras and Guarro 6

This study has several limitations. Data collection was performed at only 1 time point per sampling site, and the methods used for quantifying colony counts were very simple. Nevertheless, we were surprised at the ease with which large numbers of CPEs could be isolated from the unconcentrated sewage of some hospitals. All 6 hospitals that took part in this study already have a stool screening program for CPE in place, but the extent of the screening varies. Most hospitals screen patients who have been hospitalized in the past year. The hospitals with the largest clinical burden of CPE (hospitals A and B) additionally screen patients on at-risk wards like Hematology and Intensive Care. Finally, we did not exclude the possibility that the CPE came from staff because personnel are not routinely screened for CPE carriage.

The results of this study suggest that large numbers of CPEs in hospital sewage may strengthen the case for a screening program if none exists. The microbial ecology of resistant bacteria in the sewage system, the risk of environmental contamination, and the role of Enterobacter species and Aeromonas species in the dissemination of carbapenemase genes in the environment remain to be studied.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Delphine Cao, Peck Lay Tan, Janet Cheng, and Jeanette Teo for technical assistance. The authors gratefully acknowledge the help provided by the facilities and laboratory staff in our respective institutions.

Financial support. No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.