To the Editor—Despite profession-specific competencies Reference Carrico, Rebmann, English, Mackey and Cronin1 and evidence that infection prevention and control (IPC) training reduces infection risk, Reference Koo, McNamara and Lansing2–Reference Sahiledengle, Gebresilassie, Getahun and Hiko5 most IPC training targets physicians and nurses, with relatively little material focused on other healthcare professionals (HCPs). In 2020, the Nebraska Infection Control Assessment and Promotion (ICAP) program collaborated with the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services (NE DHHS) through a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to deliver IPC training to frontline HCPs. Our program emphasized training for groups not frequently targeted by traditional IPC curricula. We performed a learning needs assessment to assist with curricula planning by asking participants what they perceived as barriers to IPC training, how and from whom they preferred to receive IPC training, and in which IPC topics they most perceived the need for additional training. Here, we report our findings among nursing assistants and dental professionals, 2 populations whose IPC training needs are relatively unstudied.

We distributed an online survey to Nebraska’s frontline HCPs via local professional societies and ICAP e-mail listservs, ICAP webinars, ICAP social media platforms, and the NE DHHS weekly newsletter. The survey asked respondents to identify their professional role, preferred sources and formats of training, and perceived need for additional training across multiple IPC topics. Survey responses from nursing assistants and dental professionals were analyzed using descriptive statistics, and response ratios were compared using the χ2 test.

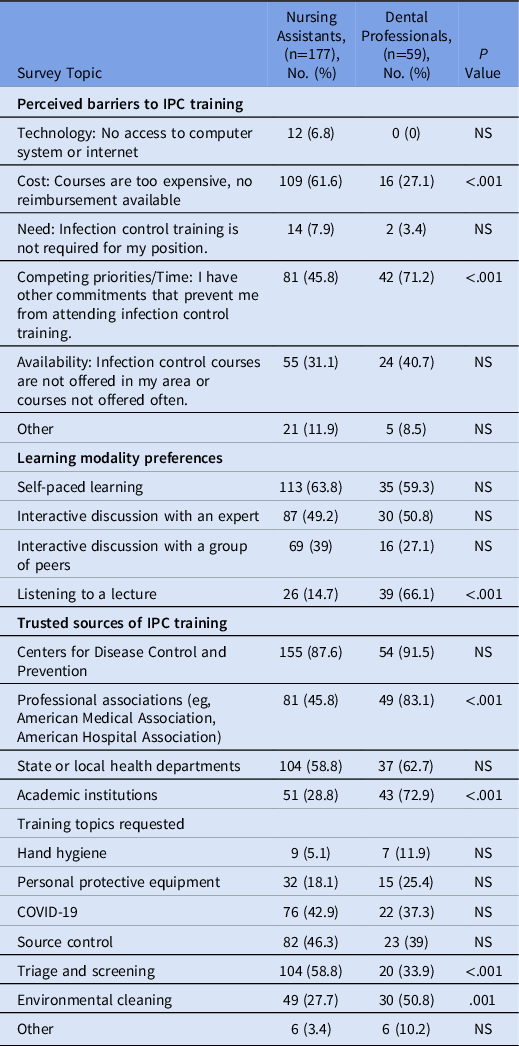

In total, 177 nursing assistants and 59 dental professionals completed our survey; slightly less than half of each group (48% and 49%) reported practicing in a rural setting. The survey responses by nursing assistants and dental professionals are summarized in Table 1. We identified several important differences. First, although nursing assistants and dental professionals identified the same top 3 barriers to participating in IPC training, nursing assistants were more often concerned about cost and dental professionals were more often concerned about the time commitment. Second, although majorities in both groups preferred self-paced training, nursing assistants were far less interested in attending a traditional lecture format than were dental professionals. Third, although trust in all sources of IPC training was lower among nursing assistants versus dental professionals, this was particularly true for academic institutions and professional associations, whereas both groups had high confidence in the CDC. Finally, we noted greater interest in training on triage and screening among nursing assistants and greater interest in training on environmental cleaning among dental professionals. These data suggest that effective IPC training programs for frontline HCPs should be tailored to their individual audiences, both in format and content.

Table 1. Responses to an IPC Learning Needs Assessment Survey

Note. IPC, infection prevention and control; NS, not significant.

Based on these survey data, we suggest that IPC trainings for these audiences focus on digital modalities (eg, prerecorded online learning modules and short-format live webinar series) to mitigate the respondent’s main highlighted barriers of cost, regional access to training, and busy schedules. We believe modular IPC curriculum, with material that can be presented in multiple modalities and rapidly adapted to meet specific audience needs, may be particularly effective. For example, a lecture on an IPC topic might be written with 20- and 60-minute variants that go into more or less detail and provide optional points to stop for question-and-answer sessions: These same materials could then be easily presented at both a 30-minute live “lunch and learn” webinar session for nursing assistants or delivered as an on-demand, prerecorded, 60-minute didactic lecture for dental professionals, meeting each group’s unique preferences.

Our survey results suggest that IPC training that is vetted and approved by widely trusted authorities such as the CDC may get more audience buy-in versus programs produced solely by local institutions for some HCP groups. Our data also suggest that IPC training curricula should be optimized for different professionals. Dental professionals requested training in environmental cleaning, reflecting their work setting and instruments used, which differs from other HCPs. Nursing assistants most requested source control as a training topic, which reflects job duties that often include interacting with a large volume of patients in settings such as hospitals or long-term care facilities. Providing IPC curricula tailored to unique HCP roles is likely to improve both the perceived and actual value of training for those audiences.

Our survey provided novel insight into training modality preferences, topics of interest, and perceived barriers to training among 2 understudied professional groups in healthcare. Small sample size, a regional survey population, and unknown survey response rate are important limitations of our findings. These data can be utilized to design customized IPC training curricula that maximize engagement in specific fields. Further research may focus on correlating these survey results to the preferences of other HCPs, allowing for potential training overlap and cost reduction. Additional studies should also examine the effectiveness of customized training curricula with the use of before-and-after surveys on IPC competence.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This work was supported by the CDC 2020 ELC Firstline IPC Training Supplement grant to the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article. M.S.A. has received investigator-initiated research grant support from Merck & Co. for unrelated work.