No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 September 2014

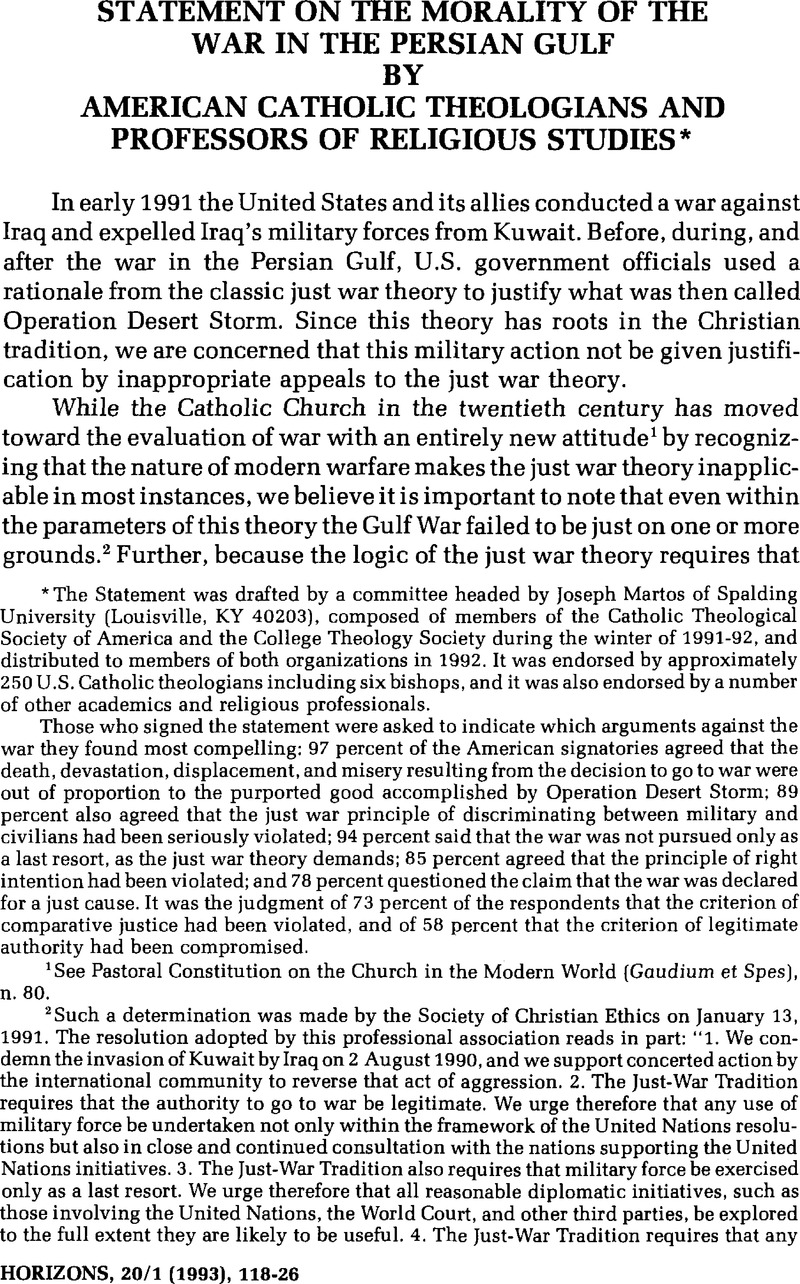

The Statement was drafted by a committee headed by Joseph Martos of Spalding University (Louisville, KY 40203), composed of members of the Catholic Theological Society of America and the College Theology Society during the winter of 1991-92, and distributed to members of both organizations in 1992. It was endorsed by approximately 250 U.S. Catholic theologians including six bishops, and it was also endorsed by a number of other academics and religious professionals.

Those who signed the statement were asked to indicate which arguments against the war they found most compelling: 97 percent of the American signatories agreed that the death, devastation, displacement, and misery resulting from the decision to go to war were out of proportion to the purported good accomplished by Operation Desert Storm; 89 percent also agreed that the just war principle of discriminating between military and civilians had been seriously violated; 94 percent said that the war was not pursued only as a last resort, as the just war theory demands; 85 percent agreed that the principle of right intention had been violated; and 78 percent questioned the claim that the war was declared for a just cause. It was the judgment of 73 percent of the respondents that the criterion of comparative justice had been violated, and of 58 percent that the criterion of legitimate authority had been compromised.

1 See Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes), n. 80.

2 Such a determination was made by the Society of Christian Ethics on January 13, 1991. The resolution adopted by this professional association reads in part: “1. We condemn the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq on 2 August 1990, and we support concerted action by the international community to reverse that act of aggression. 2. The Just-War Tradition requires that the authority to go to war be legitimate. We urge therefore that any use of military force be undertaken not only within the framework of the United Nations resolutions but also in close and continued consultation with the nations supporting the United Nations initiatives. 3. The Just-War Tradition also requires that military force be exercised only as a last resort. We urge therefore that all reasonable diplomatic initiatives, such as those involving the United Nations, the World Court, and other third parties, be explored to the full extent they are likely to be useful. 4. The Just-War Tradition requires that any exercise of military force be proportionate. We urge that if war begins, the destruction of military targets be restricted to what is indispensable to the objectives outlined in the United Nations resolutions, and that reasonable account be taken of the dangers of escalation. 5. The Just-War Tradition requires the intention of creating a just peace. In the midst of this crisis, we must not forget the problems of collective security and the conditions making for injustice and instability in the region, such as the recurrent questions of self determination for all the peoples of the Middle East, the tragedy of Lebanon, and the disputes over the oil fields shared by Iraq and Kuwait.… Given the above considerations, a majority of those of us assembled, as we ourselves seek to apply the above criteria, conclude that it would be unjustifiable for the United States, even in concert with other forces, to take offensive military action in the Gulf at this time” (CSSR Bulletin 20/2 [04 1991]: 44).Google Scholar

3 See the letter of Archbishop John Roach, Chair of the United States Catholic Conference International Policy Committee, to U.S. Secretary of Defense Cheney, Richard, “After the Gulf War: Issues of Conscience” (10 23, 1991) in Origins 21/22 (11 7, 1991), 352–53.Google Scholar

4 See, e.g., Mahoney, Archbishop Roger, “Mahoney Letter on Just War Affirmed,” Origins 20/24 (11 20, 1990): 384–86.Google Scholar (The introduction to this letter explains that at their meeting on November 12 the U.S. bishops adopted this letter “as their own.”); Pilarczyk, Archbishop Daniel, “Letter to President Bush: The Persian Gulf Crisis,” Origins 20]25 (11 29, 1990); 398–400;Google ScholarRoach, Archbishop John, “Debate on the Persian Gulf: Essential Questions,” Origins 20/28 (12 20, 1990); 457–60;Google ScholarPaul, Pope John II, “War, A Decline for Humanity,” Origins 20/33 (01 24, 1991); 525–31Google Scholar, and “The Pope's Letters to Bush and Hussein,” ibid., 534-35; Quinn, Archbishop John, “Can There Be a Just War Today?” Origins 20/38 (02 28, 1991): 623–25;Google ScholarChristiansen, Drew, “The Ethics of U.S. Strategies in the Persian Gulf,” America 163/18 (12 8, 1990); 460–62;Google ScholarDrinan, Robert, “Persian Gulf War Fails to Qualify as Just,” National Catholic Reporter 27/15 (02 8, 1991): 2;Google Scholar and Fox, Tom, Iraq: Military Victory, Moral Defeat (Kansas City, MO: Sheed and Ward, 1991).Google Scholar

5 E.g., Message and Resolution from the Executive Coordinating Committee of the National Council of Churches (September 14, 1990); Message and Resolution from the General Board of the National Council of Churches (November 15,1990); “War Is Not the Answer: A Message to the American People” (December 21, 1990) signed by leaders of eighteen churches and interchurch organizations, including Episcopal, Orthodox, Baptist, Lutheran, Methodist, Presbyterian, UCC, Reformed, Brethren, NCC, WCC, and Church Women United; telegram sent to President Bush by thirty-two church leaders (January 15, 1991) from many of the above-mentioned denominations, and also Disciples of Christ, AME, community churches, evangelicals, Moravians, Friends and Swedenborgians;’ “A Call to the Churches” (February 12, 1991), signed by 142 church leaders at the Seventh Assembly of the World Council of Churches. Texts of these statements and others are provided in Johnson, James Turner and Weigel, George, Just War and the Gulf War (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1991).Google Scholar

6 See Wallis, Jim, “The Forgotten Moral Issues,” The Progressive 55/3 (03 1991): 30–32;Google ScholarLackey, Douglas P., “Bush's Abuse of Just War Theory,” Concerned Philosophers for Peace Newsletter 11/1 (Spring 1991): 3–4;Google Scholar James P. Sterba, “War with Iraq: Just Another Unjust War,” ibid., 4-5; Lopez, George A., “The Gulf War: Not So Clean,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 47/7 (09 1991): 30–35;CrossRefGoogle ScholarRothberg, Donald, “Buddhist Perspectives on and Responses to the Persian Gulf War,” Religious Perspectives on the Conflict in the Persian Gulf (papers presented at the 1991 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Religion), 43–54;Google ScholarWalzer, Michael, “Justice and Injustice in the Gulf War” in DeCosse, David E., ed., But Was It Just? Reflections on the Morality of the Gulf War (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 1–17;Google Scholar Stanley Hauerwas, “Whose Just War? Which Peace?” in ibid., 83-105; and Geyer, Alan and Green, Barbara, Lines in the Sand (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox, 1992).Google Scholar

7 See St. Augustine, The City of God, Book I, ch. 21; Book IV, chs. 3-6, 14-15.

8 See “Modern War and the Christian Conscience,” translated from La Civiltà Cattolica (07 6,1991) by Shannon, William, Origins 21/28 (12 19, 1991): 452–53;Google Scholar also available (trans. Heinigg, Peter) in But Was It Just? 107–25.Google Scholar

9 See National Conference of Catholic Bishops, The Challenge of Peace: God's Promise and Our Response (05 3, 1983), nn. 80-110.Google Scholar Other explanations of the just war criteria can be found in, e.g., Phillips, Robert L., War and Justice (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984)Google Scholar, and Flynn, Eileen P., My Country Righ tor Wrong? (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1985).Google Scholar

10 For an extensive review of articles and statements on the application of just war criteria to the Gulf War, see Walters, Gregory J., “Just War Casuistry and the Gulf War: Disputed Questions” in Religious Perspectives on the Conflict in the Persian Gulf (papers presented at the 1991 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Religion), 18–42Google Scholar, available from the author, Department of Theology, St. Mary's University, San Antonio, TX 78228-8585.

11 A wide range of reasons for going to war was presented during the hearings of the Senate Armed Services Committee in November and December 1990 (see testimony by Kissinger, Henry, “How to Cut Iraq Down to Size,” 238–42Google Scholar, and Milhollen, Gary, “How Close Is Iraq to the Bomb?” 243–50Google Scholar in Sifry, Micah and Cerf, Christopher, eds., The Gulf War Reader: History, Documents, Opinions [New York: Times Books, Random House, 1991])Google Scholar and during the debate leading to the Joint Congressional Resolution of January 12, 1991 (see Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report, 49/2 [01 12, 1991]: 132–34).Google Scholar For documentation of the president's range of reasons, see “Persian Gulf Crisis Brings Forth a Variety of Rationales, Objectives,” Congressional Quarterly Almanac (Vol. XLVI) 1990 (Washington, DC, 1991), 744–45.Google Scholar See also the speeches of Bush, George reprinted in The Gulf War Reader (08 8, 1990): 197ff.;Google Scholar (November 8, 1990): 228f.; (January 16, 1991): 311ff.; and (February 27, 1991): 449ff.

12 It can be questioned whether the cause of defending Saudi Arabia could have justified an offensive military action since it is uncertain that Iraq ever intended to invade Saudi Arabia. Theodore Draper (“The True History of the Gulf War,” The New York Review of Books 29/3 [01 30, 1992]: 40–41)Google Scholar argues that the threat of an invasion was an interpretation of the administration which ran counter to information received from the CIA and the Defense Intelligence Agency: “As General Powell later admitted, Iraqi forces could have moved into Saudi Arabia virtually unopposed for three weeks after having taken over Kuwait.” See also “Public Doesn't Get Picture with Gulf Satellite Photos,” In These Times 15/14 (02 27–03 19, 1991): 7.Google Scholar The editors of the bimonthly Middle East Report conclude, “There is no evidence that Iraq planned to invade Saudi Arabia” (The Gulf War Reader, 38).

13 ”War is permissible only to confront ‘a real and certain danger,’ i.e., to protect innocent life, to present conditions necessary for decent human existence, and to secure basic human rights” (The Challenge of Peace, n. 86). Murray, John Courtney traces this development in Catholic teaching to Pope Pius XII in “Remarks on the Moral Problem of War,” Theological Studies 20/1 (1959): 45–47.CrossRefGoogle Scholar Pope John Paul II made 56 speeches during the Gulf Crisis, stating repeatedly, “War is an adventure with no return” (see Hebblethwaite, Peter, “Pope Expands Gulf War Debate Beyond ‘Just War’ Jousting,” National Catholic Reporter 28/13 [01 31, 1992]: 10–11).Google Scholar

14 Witness the lack of military response to China's annexation of Tibet, Indonesia's annexation of East Timor, Turkey's occupation of Cyprus, Syria's invasion of Lebanon, and Israel's occupation and annexation of various territories. For a thorough exposition of this argument see Parry, Richard D., “The Gulf War and the Just War Doctrine,” America 164/15 (04 20, 1991): 442–45.Google Scholar For most observers not concerned with the moral debate, the primary causes were economic and political, not humanitarian (see Aarts, Paul and Renner, Michael, “Oil and the Gulf War: Defining the Terms of Dominion,” Middle East Report 21/4 [07–08 1991]: 25–29;CrossRefGoogle Scholar also Friedman, Thomas L., “Confrontation in the Gulf: U.S. Gulf Policy—Vague ‘Vital Interest’,” The New York Times [08 12, 1990], A1).Google Scholar

15 Draper, (“True History of the Gulf War,” 38–45)Google Scholar, summarizes information from eight recently-released books about the war. On p. 41 he reports that Egypt received $13.7 billion in debt cancellations for supporting the war, and Syria was given $2.7 billion in grants and loans. “Turkey protected its $500 million a year in military aid,” whereas “Yemen was cut off from $70 million in foreign aid for voting the wrong way” in the United Nations. The U.S. rewarded China for its not vetoing the U.N. resolutions with a warming of diplomatic relations, which had been chilly since the Tiananmen Square massacre.

16 This dimension of the Persian Gulf Crisis is best documented in Smith, Jean Edward, George Bush's War (New York: Henry Holt, 1992).Google Scholar See also Schroth, Raymond A. (“Media Mirrors Mixed Up America after Gulf War,” National Catholic Reporter 28/13 [01 31, 1992]: 16)Google Scholar regarding the manipulation of communications media; Horgan, John, (“Up In Flames,” Scientific American 264/5 [05 1991]: 20)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, regarding the government prohibition on scientists discussing the war's environmental effects with reporters; Rowse, Arthur E. (“Flacking for the Emir,” The Progressive 55/5 [05 1991]: 20–22)Google Scholar regarding anti-Iraq propaganda; and articles by Schanberg, Sydney H., Fisk, Robert, and Cronkite, Walter in The Gulf War Reader, 368–84.Google Scholar

17 Draper, Theodore, “The Gulf War Reconsidered” (The New York Review of Books 39/1–2 [01 16, 1992]: 46ff.)Google Scholar summarizes and excerpts information from Kuwait and Iraq: Historical Claims and Territorial Disputes by Richard Schofield, Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar by Jill Crystal, and other recently published books documenting Iraqi and Kuwaiti disputes over territory and rights (see also Kalidi, Walid, “Iraq and Kuwait: Claims and Counterclaims,” The Gulf War Reader, 57–65).Google Scholar

18 Regarding human rights abuses during 1990 in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Syria, Turkey, and other members of the coalition, see Amnesty International Report, 1991 (countries listed alphabetically). On the other hand, abuses and even atrocities in Iraq before its invasion of Kuwait were diplomatically minimized by the U.S. government while it was supporting Saddam Hussein, which also reduces its claim to absolute justice; see Nordland, Rod (“Saddam's Secret War,” Newsweek 117/23 [06 10, 1991]: 28–30)Google Scholar which recounts the campaign against the Kurds from 1987 to 1990. On demonizing the enemy and other psycho-sociological dimensions of American war preparations, see Mack, John E. and Rubin, Jeffrey Z., “Is This Any Way to Wage Peace?” The Gulf War Reader, 317–19.Google Scholar

19 See Clare, Michael T., “Fueling the Fire: How We Armed the Middle East,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 47/1 (01–02 1991): 19–26.Google Scholar More recently, three articles by Frantz, Douglas and Waas, Murray in The Los Angeles Times, 02 23–25, 1992Google Scholar, and syndicated to other newspapers, e.g., The Morning Call (Allentown, PA): “Secret Effort by Bush Helped Iraq” (February 23), A1+, “Bush Pressured Bank to Help Iraq” (February 24), A1 +, and “U.S. Aid to Iraq Helped Saddam Prepare for War” (February 25), A3 summarize the evidence that billions of dollars in U.S. aid and credit were given to Iraq during the Reagan and Bush administrations.

20 See “The Glaspie Transcript: Saddam Meets the U.S. Ambassador (07 25, 1990)” in The Gulf War Reader, 122ff.Google Scholar, in which April Glaspie is reported to have said “…we have no opinion on Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait” (130). For the ambassador's explanation before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, see Watson, Russellet al., “Was Ambassador Glaspie Too Gentle with Saddam?” Newsweek 117/13 (04 1, 1991): 17.Google Scholar

21 Elliott, Kimberly, Hufbauer, Gary and Schott, Jeffrey, “The Big Squeeze: Why the Sanctions on Iraq Will Work,” The Washington Post (12 9, 1990)Google Scholar, reprinted in The Gulf War Reader, 255-59, argues from historical precedent to the effectiveness of economic sanctions. Newman, Peter C. (“Why Bush Should Have Delayed the War,” Maclean's 104/5 [02 4, 1991]: 48)Google Scholar points out that the president ignored CIA reports that the sanctions were effective and would probably succeed in time.

22 See Bierman, Johnet al., “At the Brink,” Maclean's 104/4 (01 14, 1991): 20–22Google Scholar regarding the last-minute negotiations; Cockburn, Alexander (“The Press and the ‘Just War’,” The Nation 252/6 [02 18, 1991]: 187)Google Scholar mentions some of the ways that the U.S. undermined the peace initiatives of other countries.

23 The U.S. intention to defend its access to oil in the Middle East has been called the “Carter Doctrine,” articulated by President Jimmy Carter in his 1980 State of the Union Address: “An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.” In accordance with this intention, military airfields and command bunkers were constructed in Saudi Arabia, on which logistical foundation operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm were initially mounted (see Historic Documents of 1980 [Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1981], 33;Google ScholarGerson, Joseph and Birchard, Bruce, eds., The Sun Never Sets: Confronting the Network of Foreign U.S. Military Bases [Boston: South End, 1991], 275–307).Google Scholar

24 Church, George (“Keeping Hands Off,” Time 137/14 [04 8, 1991]: 22–25)Google Scholar, reports on “the carnage inside Iraq” while the allies took no action. Viorst, Milton (“A Reporter at Large: After the Liberation,” The New Yorker 6/32 [09 30, 1991]: 58–60)Google Scholar recounts human rights abuses and political repression in Kuwait after the war, as does Alexander, Ian (“The Peace of Kuwait,” National Review 43/19 [10 21, 1991]: 20–21).Google Scholar

25 Duffy, Brian, “The Hundred Hour War,” U.S. News and World Report 110 (03 11, 1991): 11–22Google Scholar, notes on page 18 that many Iraqis never had a chance to surrender. Waller, Douglas and Barry, Johnet al. (“The Day We Stopped the War,” Newsweek 119/3 [01 20, 1992]: 16–25)Google Scholar describe the human devastation along Iraq's Highway 6, dubbed by journalists “The Highway of Death.”

26 Before the initiation of the land war, estimates of possible casualties among coalition forces ranged from 20,000 to 45,000 (see “The Costs of War,” The Nation 251/22 [12 24, 1990]: 792;Google Scholar“U.S. Invasion of Iraq: Appraising the Option,” The Defense Monitor 19/8 [1990]: 7).Google Scholar Various estimates have been made of the number of actual casualties. The Newsweek article cited in the preceding footnote gathers data on p. 18 from the U.S. Department of Defense, various intelligence agencies and Greenpeace USA in concluding that 549 allied military were killed in combat or in fatal accidents, 70,000-115,000 Iraqi military were killed in battle, 2,500-3,000 civilians were killed during the air war, and that 100,000-120,000 more civilians have died since then from civil unrest and war-related ailments.

27 The cost of the war to the countries that agreed to pay for it has been estimated at between $60 billion and $160 billion, depending on the amount of interest paid on loans taken out to pay for the war. The rehabilitation of Kuwait and Iraq has been estimated at $270 billion in 1991 dollars. These figures do not include billions of dollars of indirect losses suffered by third parties as a result of the war due to reductions in air travel and tourism to the Middle East, to agricultural damage in India and elsewhere because of air pollution from burning oil wells, etc. (see Walters, “Just War Casuistry,” 34).

28 “The ‘Spoils’ of War: Damaged Economies, Devastated Ecologies,” U.N. Chronicle 28/2 (06 1991): 16–18Google Scholar reports that twenty-one countries were severely affected by the war both economically and ecologically. An estimated four to six million barrels of oil were released into the Persian Gulf, and approximately five million barrels of oil were being consumed every day by the 500 wells ignited during the war, which generated more than a half million tons of aerial pollutants daily (see Canby, Thomas Y., “After the Storm,” National Geographic 180/2 [08 1991]: 2–32, esp. 10 and 16).Google Scholar

29 Deaths, Needless in the Gulf War: Civilian Casualties During the Air Campaign and Violations of the Laws of War by Middle East Watch (Washington, DC: Human Rights Watch, 1991)Google Scholar documents the extensive destruction of Iraq's infrastructure as well as the bombing of civilian targets that had little or no military significance. See also Lewis, Paul (“U.N. Survey Calls Iraq's War Damage Near-Apocalyptic,” The New York Times [03 22, 1991], Al+)Google Scholar which reports that “about 9,000 Iraqi homes were destroyed or damaged beyond repair during the war, including 2,500 in Baghdad and another 1,900 in Basra, and that about 72,000 people have been left homeless.”

30 See Moreau, Ron, “Saddam's Slaughter,” Newsweek 117/15 (04 15, 1991); 22–26;Google ScholarChua-Eoan, Howard G., “Defeat and Flight,” Time 137/15 (04 15, 1991): 18–23.Google Scholar

31 “The Gulf: 5 Million and Counting …,” U.N. Chronicle 28/3 (09 1991): 47–50Google Scholar, describes the plight of 1.5 million Kurds, 800,000 Shiites and 3 million “guest workers” in Kuwait and Iraq who were temporarily or permanently displaced by the war and its aftermath. See also Clifton, Tony, “Burying the Babies,” Newsweek 117/16 (04 22, 1991): 24–26.Google Scholar

32 See “The Fury of Desert Storm,” U.S. News and World Report 110/9 (03 11, 1991): 58–73, esp. 68.Google Scholar“Special Missions Assess War Damage,” U.N. Chronicle 28/2 (06 1991): 15Google Scholar, reports that Iraq had been relegated to “a pre-industrial age.” Gordon, Michael R. (“Pentagon Study Cites Problems with Gulf Effort,” The New York Times [02 23, 1992], A1 +)Google Scholar refers to a recent U.S. government report which admits that there was much more collateral damage during the war than originally reported.

33 Shortly after the war, “Air Force Chief of Staff General A. McPeak … revealed that of the 88,500 tons of bombs dropped on Iraq and occupied Kuwait, only 7 percent were precision guided bombs. Of the remaining nonprecision bombs, 70 percent missed their targets,” reports Wall, James M. (“Winning the War, Losing Our Souls,” The Christian Century 108/11 [04 3, 1991]: 356).Google Scholar

34 Bartholet, Jeffrey and Barry, John, “Inside Iraq, Devastation and Resignation,” Newsweek 117/23 (06 10, 1991): 30.Google Scholar “A Harvard team that visited Iraq in late April estimated that 170,000 children will die of gastrointestinal disease complicated by malnutrition as a result of the war,” reported Burleigh, Nina (“Watching Children Starve,” Time 137/23 [06 10, 1991]: 56–58).Google Scholar