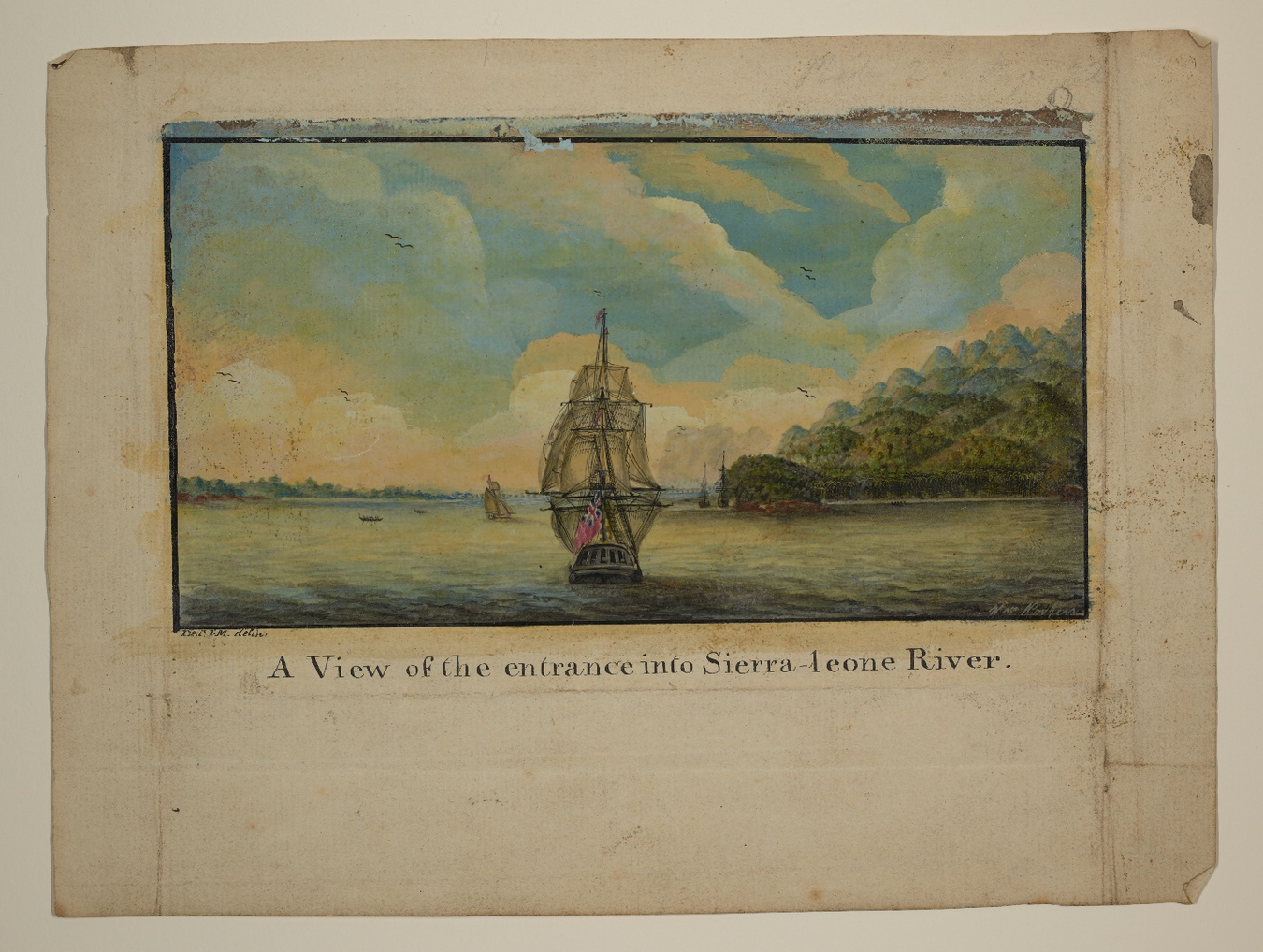

In 2017, the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections at the Firestone Memorial Library, Princeton University, acquired a collection of papers related to John Matthews that was previously unknown to historians.Footnote 1 Matthews was a British naval officer and enslaver in the late-eighteenth century with close ties to the region of greater Sierra Leone, which he defined as extending from roughly the Rio Nuñez in the present-day nation of Guinée-Conakry, to Cape St. Ann in the south of the present-day nation of Sierra Leone.Footnote 2 Kelly Bolding, a project archivist at Princeton, and Don Skemer, a manuscripts curator, have already summarized the broad contents of the “Captain John Matthews Papers” for potential researchers.Footnote 3 The following archives report will focus on two of the four logbooks included in the collection. These books cover Matthews’s employment as co-agent for a London-based slaving firm, named Samuel Hartley and Company, between April of 1785 and May of 1787.Footnote 4 Matthews’s operations were based out of a factory that was situated in “White Man’s Bay,” an inlet on the northern coast of the Sierra Leone Peninsula.Footnote 5 Matthews represented this coast himself in a series of watercolor images that he produced at the time of his residency (see Figure 1). More specifically, this report will suggest three topics for which these journals might be of value to scholars of early-modern West Africa. These topics are the local workings of the transatlantic slave trade in greater Sierra Leone; the production of European knowledge about Africa and Africans; and the history of the region in the years preceding the settlement of Freetown.

Figure 1. Original watercolor image of “A View of the entrance into Sierra-leone River,” Captain John Matthews Papers, Manuscripts Division, Special Collections, Firestone Memorial Library, Princeton University Libraries, C1575, Box 2, Folder 4. In the second edition of his travelogue, A Voyage to the River Sierra-Leone, Matthews published a series of black and white sketches that portrayed the region. The image shown here is one of four original watercolors that have survived in the Captain John Matthews Papers. It depicts the entrance to the Sierra Leone River from the deck of a ship offshore in the Atlantic Ocean. Courtesy of Princeton University Library.

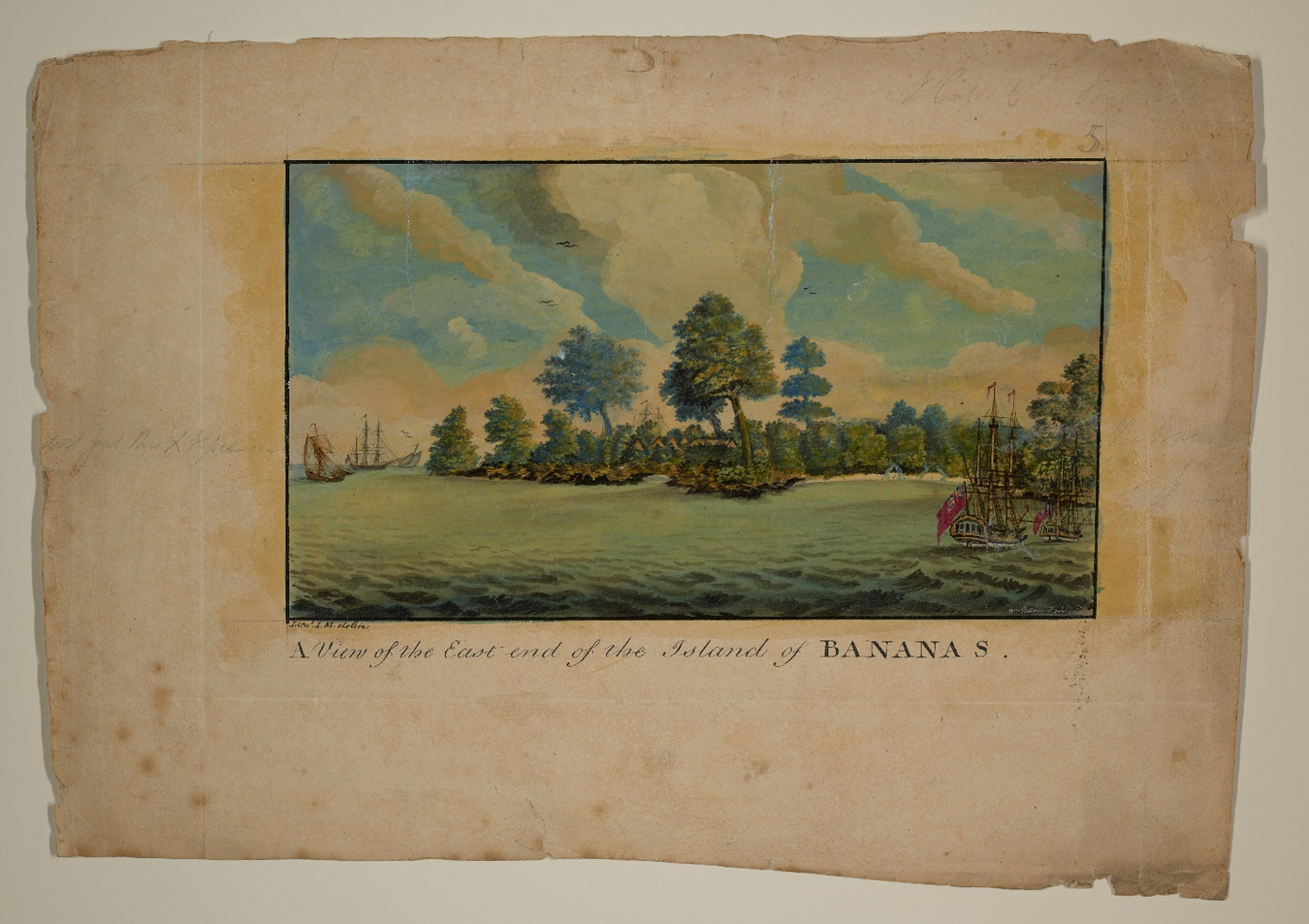

First, Matthews’s logbooks are valuable because they provide insight into the local workings of the transatlantic slave trade in a coastal region that was defined by neither the presence of a centralized African state or an official European firm. Scholars of the slave trade in precolonial West Africa have long recognized, in the words of the historian Toby Green, that “There was not one Atlantic slave trade, but [instead] many trades wreaking many different effects….”Footnote 6 In comparison to some other areas of the West African coast where European enslavers operated—like present-day Senegal, The Gambia, Ghana, Benín, and Congo-Angola—there were no large European forts and few chartered companies operating in the region of Sierra Leone. There were also no large African states or kingdoms in direct contact with European traders, even though the inland state of Fuuta Jalon did exercise a great influence over the coastal slave trade.Footnote 7 Also, unlike in southeastern Nigeria, white traders were allowed to maintain factories on the coast.Footnote 8 Like his contemporaries, Matthews negotiated with small host communities in a “landlord-stranger” relationship, in which he paid ground rent and customs duties for protected residency and permission to conduct trade by “boating” up and down the shore.Footnote 9 In the process, he drew upon shared traditions of Afro-European commerce that went back to the fifteenth century, and that were rooted in cultures of ancestry, marriage, language, migration, and credit.Footnote 10 He married a local woman as a “country wife” and had a son with her; he relied upon skilled and gendered Temne labor to run his business; and he engaged in long-tested customs of Afro-European commerce that were meant to secure trust and credit.Footnote 11 He also interacted with a diversity of sovereign local communities and a constellation of European and mixed-race residents who functioned as local leaders. He depicted the home of one of these leaders, the Anglo-African trader James Cleveland, in one of his drawings (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Original watercolor image of “A View of the East end of the Island of Bananas,” Captain John Matthews Papers, Manuscripts Division, Special Collections, Firestone Memorial Library, Princeton University Libraries, C1575, Box 2, Folder 1. This image is the second of four watercolor drawings of Sierra Leone included in the Captain John Matthews Papers. It depicts the Banana Islands off the southern shore of the Sierra Leone Peninsula. Matthews regularly sailed to the Banana Islands to conduct business with its resident, a mixed-race trader by the name of James Cleveland. Cleveland’s home is barely visible here amongst the cluster of trees in the middle of the picture. Matthews later described this home as being “furnished in the English stile, but built…in the country manner.” Courtesy of Princeton University Library.

Second, Matthews’s logbooks are valuable because they offer an opportunity to examine the production of European knowledge about Africa and Africans. Scholars have found a number of logbooks by European enslavers who operated off the coast of greater Sierra Leone, and they have sometimes been able to see how white enslavers constructed public knowledge of West Africa in the early-modern period over a series of revised texts.Footnote 12 Nonetheless, it is rare to uncover logbooks by an enslaver who produced so much other contemporary written material about the area in which he operated.Footnote 13 Matthews was part of a generation of enslavers who produced proslavery work on Africa and Africans during the British government’s investigation into the economics and morality of the transatlantic slave trade. After returning from Sierra Leone in 1788, he worked as a delegate for the anti-abolitionist lobby.Footnote 14 He testified against the abolitionists before the Privy Council and the House of Commons; he protested abolition in private letters to the chair of the investigation; and, finally, he published a proslavery travel book about Sierra Leone, entitled A Voyage to the River Sierra-Leone. Footnote 15 Historians can now compare Matthews’s logbooks with his testimonies and his travel account in order to better see how Europeans produced public knowledge of a region like Sierra Leone across different textual genres and for a distinct political agenda.Footnote 16 They can study in a more particular way which aspects of life in West Africa enslavers chose to silence and which aspects they chose to emphasize for their own political purposes. To mention just one example here, Matthews represented Sierra Leone in both his testimony and his travelogue as a picturesque landscape of natural abundance and scientific curiosity. This representation can be seen in the instructive nature of the images that he produced (see Figure 3). By doing so, he downplayed the real threat that the climate posed for any potential migrants. It is only in Matthews’s unpublished logs that we learn just how sick the free and enslaved people at his factory became. Matthews himself almost died after he became “full ill” for two weeks in the summer of 1786.Footnote 17

Figure 3. Original watercolor image of “A View of the South side of Sierra-leone River from… Leopards Island,” Captain John Matthews Papers, Manuscripts Division, Special Collections, Firestone Memorial Library, Princeton University Libraries, C1575, Box 2, Folder 2. The third of these four watercolor images depicts the Sierra Leone Peninsula from across the river. The late-eighteenth century was a period of growing European interest in Sierra Leone, due largely to the mission of British abolitionists to establish a colony there based upon free labor. In both his testimony and his travelogue, Matthews positioned himself as an expert on the region. The dark clouds at the top of this picture almost certainly depict the Harmattan, a seasonal wind in West Africa that Matthews described as a thick smoke. The deforested slope of the mountain in the foreground was meant to show tracts of land that had been previously cultivated or newly cleared for agriculture. Courtesy of Princeton University Library.

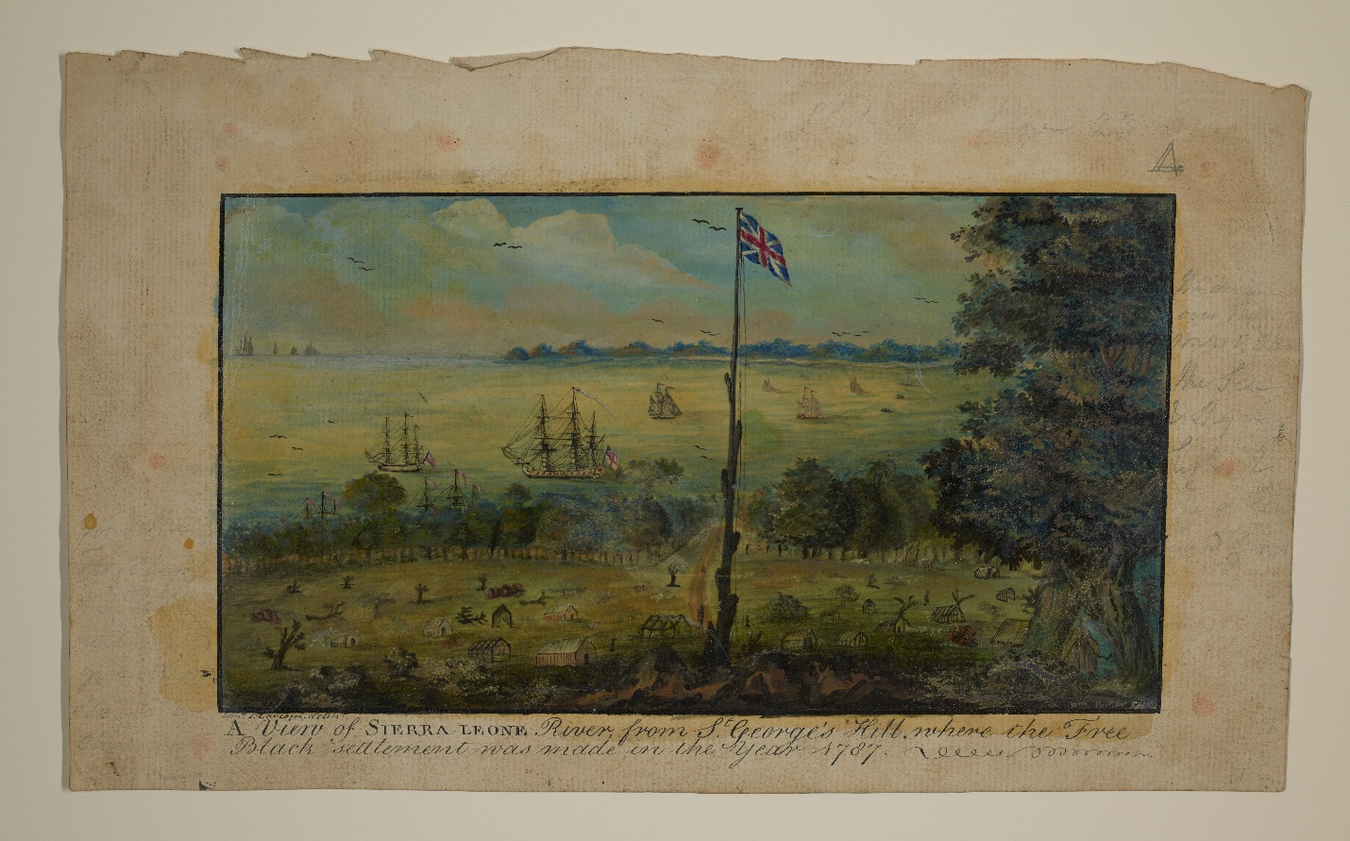

Finally, Matthews’s logbooks are valuable because they may comprise the most intimate look at life on the north coast of the Sierra Leone Peninsula immediately preceding the founding of the Sierra Leone colony. Britain established its first permanent settler colony in West Africa in 1787, when abolitionists resettled approximately 400 impoverished black residents of London on the eastern side of what is today Kroo Bay, Freetown.Footnote 18 This first cohort was followed up another five years later by a second settlement in the same location, this one comprised of roughly 1,000 black settlers from the British colony of Nova Scotia.Footnote 19 Matthews’s factory was situated only two miles to the west of this spot, and his journals cover the two years leading up to the first cohort’s arrival. This means that he was closer to Freetown, both temporally and geographically, than the other contemporary writers whom we know about, including Nicholas Owen, John Newton, and Henry Smeathman.Footnote 20 In fact, Matthews actually documented the landing of the settlers in the last entry of his log and included a black and white drawing of the event in the second edition of A Voyage. Footnote 21 The original watercolor of that drawing is included here (see Figure 4). To date, this drawing remains the only historical image that we have of the initial settlement. It portrays the black settlers erecting the colony’s first wood frame houses in an area of cleared land at the base of what is today Tower Hill.

Figure 4. Original watercolor image of “A View of Sierra-Leone River, from St. George’s Hill, where the Free Black settlement was made in the year 1787,” Captain John Matthews Papers, Manuscripts Division, Special Collections, Firestone Memorial Library, Princeton University Libraries, C1575, Box 2, Folder 3. The final image in this series of four watercolors depicts the arrival of the free black setters in 1787. In the final entry of his journal, Matthews writes that he returned to his factory from the Bay of Sherbro at 3:00 p.m. on Tuesday, 15 May, and found the settlers’ transport ships laying at anchor. This drawing was probably not created by Matthews himself, although it was first published in the second edition of his travelogue. Unlike that black and white print, this color version represents a few of the black settlers. They can be seen walking amongst the buildings and on the road that leads to the shore. Courtesy of Princeton University Library.

To end with a specific example about the Sierra Leone colony, the Captain John Matthews Papers can help us better understand the upheaval that the first black settlers experienced. On the eve of colonization, black abolitionists in London, such as Ottobah Cugoano, recognized the danger that migration to Sierra Leone posed for these potential settlers. Cugoano questioned in his pamphlet, titled Thoughts and Sentiments, whether a “free colony” could really survive “nearly on the spot” where enslavers operated.Footnote 22 His words proved to be prescient, as the first settlement was burned to the ground by the local Temne leader, King Jimmy, just a couple of years later, in December of 1789. Matthews’s logbooks allow us to see the instability that prevailed in the years before these settlers arrived. For example, they show villagers abandoning their homes in the Bay of Sherbro during wartime; captives and pawns fleeing Matthews and his patrons at “White Man’s Bay” for fear of being transported; and locals plotting to murder Matthews just as one of his predecessors, a European slave trader named John Tittle, was killed by locals in the 1770s.Footnote 23 In these ways and more, the Captain John Matthews Papers at Princeton University can serve as a valuable resource for scholars working on the history of early-modern Sierra Leone and West Africa.