Article contents

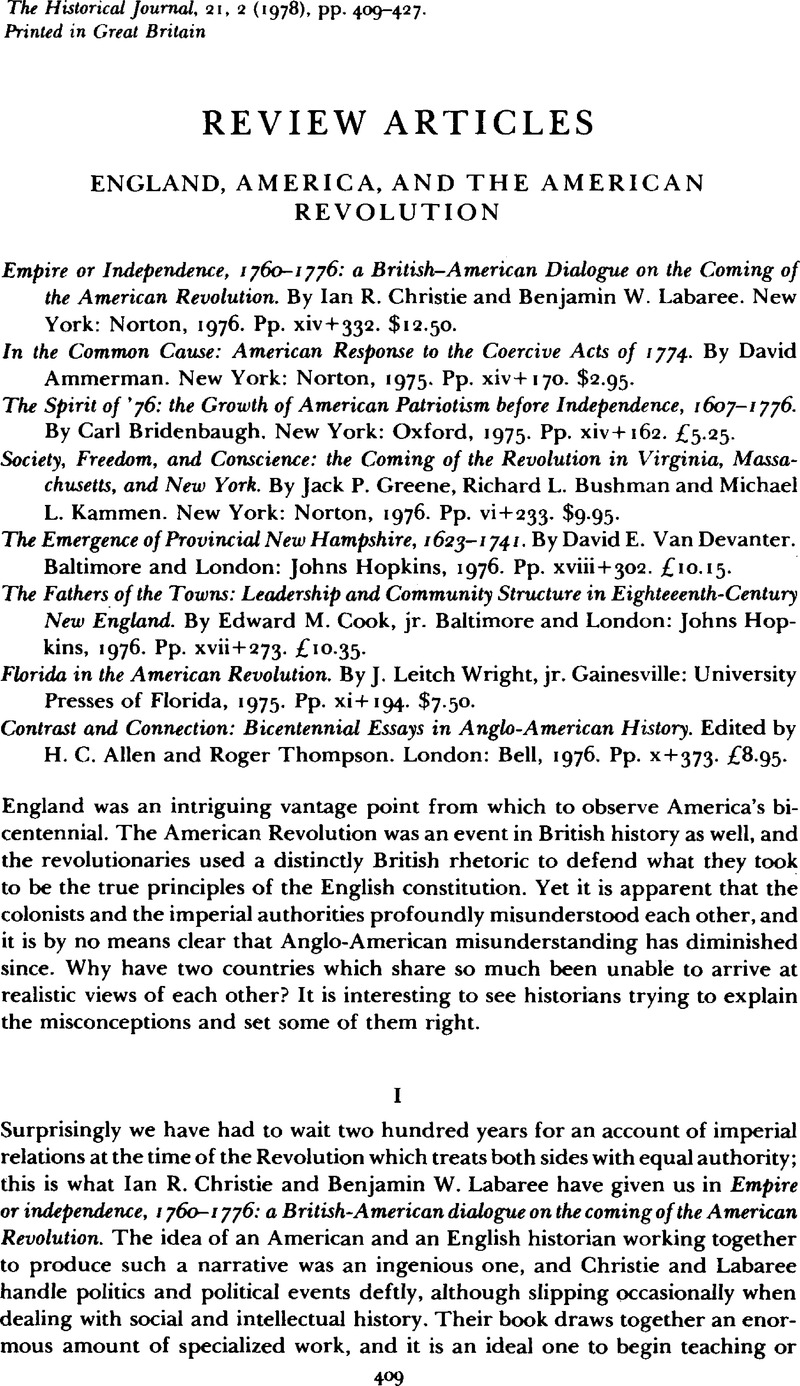

England, America, and the American Revolution

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1978

References

1 Greene, Jack P., ‘An uneasy connection: an analysis of the preconditions of the American Revolution’, in Kurtz, Stephen G. and Hutson, James H. (eds.), Essays on the American Revolution (Williamsburg, Va., 1973), pp. 65–7.Google Scholar

2 Brewer, John has made this argument in Party ideology and popular politics at the accession of George III (Cambridge, 1976), pp. 201–16.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

3 Bailyn, Bernard, ‘The central themes of the American Revolution: an interpretation’, in Kurtz, and Hutson, , Essays, p. 7.Google Scholar

4 Morgan, Edmund S., ‘The American Revolution: revisions in need of revising’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., XIV (1957), 12–13.Google Scholar

5 Such a development is in fact described in Kuroda, Tadahisa, ‘The county court system of Virginia from the Revolution to the Civil War’ (unpub. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 1970), pp. 21–4.Google Scholar

6 Wood, Gordon S., ‘Rhetoric and reality in the American Revolution’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., XXIII (1966), 27.Google Scholar

7 Isaac, Rhys, ‘Evangelical revolt: the nature of the Baptists' challenge to the traditional order in Virginia’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., XXXI (1974), 345–68.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

8 Greene, Jack P., ‘Political mimesis: a consideration of the historical and cultural roots of legislative behavior in the British colonies in the eighteenth century’, American Historical Review, LXXV (1969–1970), 344.Google Scholar

9 Ibid. p. 349.

10 Greene, , ‘Uneasy connection’, pp. 55–61.Google Scholar

11 Ibid. pp. 65–74.

12 The best summary of Bailyn's, position is his book The origins of American politics (New York, 1968)Google Scholar. The quotation is from pp. 159–60.

13 Brown, Richard D., Revolutionary politics in Massachusetts: the Boston committee of correspondence and the towns, 1772–1774 (Cambridge, Mass., 1970).Google Scholar

14 Breen, Timothy H., The character of the good ruler: a study of Puritan political ideas in New England, 1630–1730 (New Haven, 1970).Google Scholar

15 Pocock, J. G. A., The Machiavellian moment: Florentine political thought and the Atlantic republican tradition (Princeton, 1975), pp. 423–505.Google Scholar

16 Greene, , ‘Uneasy connection’, p. 71Google Scholar. For a detailed analysis of New Hampshire politics under the Wentworths see Daniell, Jere K., Experiment in republicanism: New Hampshire politics and the American Revolution, 1741–1794 (Cambridge, Mass., 1970), pp. 3–34.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

17 Murrin, John M., ‘Review article’, History and Theory, XI (1972), 243–4, 253–6, 260–7Google Scholar, and MacWade, Kevin J., ‘Worcester County, 1750–1774: a study of a provincial patronage elite’ (unpub. Ph.D. dissertation, Boston University, 1974), p. 63.Google Scholar

18 On Shirley's career see Schulz, John A., William Shirley, king's governor of Massachusetts (Chapel Hill, 1961).Google Scholar

19 Bailyn, , Origins, pp. 116–17.Google Scholar

20 Murrin, John M., ‘Anglicizing an American colony: the transformation of provincial Massachusetts’ (unpub. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale, 1966), pp. 262, 274.Google Scholar

21 Murrin, John M., ‘The myths of colonial democracy and royal decline in eighteenth-century America: a review essay’, Cithara, V (1965), 65.Google Scholar

22 Murrin, , ‘Anglicizing an American colony’, p. 262.Google Scholar

23 Waterhouse, Richard, ‘South Carolina's colonial elite: a study in the social structure and political culture of a southern colony, 1690–1760’ (unpub. Ph.D. dissertation, Johns Hopkins, 1973), pp. 51–121.Google Scholar

24 Morgan, Edmund S., American slavery, American freedom: the ordeal of colonial Virginia (New York, 1975), pp. 295–363.Google Scholar

25 Weir, Robert M., ‘“The Harmony We Were Famous For”: an interpretation of pre-revolutionary South Carolina polities’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., XXVI (1969), 487–96.Google Scholar

26 Isaac, Rhys, ‘Dramatizing the ideology of revolution: popular mobilization in Virginia, 1774–1776’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., XXXIII (1976), 368.Google Scholar

27 On Virginia see Beeman, Richard R., The old dominion and the new nation, 1768–1801 (Lexington, Ky., 1972), pp. 28–55Google Scholar; on South Carolina see Hoffman, Ronald, ‘The “disaffected” in the revolutionary South’, in Young, Alfred F. (ed.), The American Revolution: explorations in the history of American radicalism (DeKalb, Ill., 1976), pp. 293–5.Google Scholar

28 Plumb, J. H., Sir Robert Walpole, the king's minister (London, 1960)Google Scholar, passim, and Owen, John B., The rise of the Pelhams (London, 1957), pp. 1–86.Google Scholar

29 Brewer, , Party ideologyGoogle Scholar, passim.

30 Plumb, J. H., The growth of political stability in England, 1675–1725 (London, 1967), pp. 22, 25, 34, 103, 161–3CrossRefGoogle Scholar. The quotation is from p. 34.

31 Namier, Lewis, The structure of politics at the accession of George III (London, 1963 edn), pp. 150–7.Google Scholar

32 Bailyn, Bernard, ‘Comment’, American Historical Review, LXXV (1969–1970), 361–3.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

33 See, for example, the comments of Governor James Glen of South Carolina that the powers of the royal governor ought to be strengthened but only if there was some way to make sure that the governor was himself virtuous; quoted in Carroll, B. R., Historical collections of South Carolina… (New York, 1836), 11, 220.Google Scholar

34 Weir, Robert M., ‘Who should rule at home: the American Revolution as a crisis of legitimacy for the colonial elite’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, VI (1975–1976), 679–700.Google Scholar

35 The best introduction to popular radicalism is the collection of essays in Young (ed.), American Revolution. The threat to the internal social order should not, however, be exaggerated; instead popular radicalism might more profitably be considered as a clue to the extraordinarily broad popular mobilization of Americans to fight the Revolution – a mobilization, nevertheless, under elite leadership.

36 There is an extensive literature on the distribution of wealth in the colonies. For recent pieces which cite the earlier works see Gary B. Nash, ‘Urban wealth and poverty in pre-revolutionary America’, G. B. Warden, ‘Inequality and instability in eighteenth-century Boston: a reappraisal’, and Ball, Duane E., ‘Dynamics of population and wealth in eighteenth-century Chester County, Pennsylvania’, all in Journal of Interdisciplinary History, VI (1975–1976), 545–644.Google Scholar

37 Daniell, , Experiment, pp. 48–51.Google Scholar

38 Martin, James K., Men in rebellion: higher governmental leaders and the coming of the American Revolution (New Brunswick, N.J., 1973).Google Scholar

39 On the development of American political thought see Wood, Gordon S., The creation of the American republic, 1776–1787 (Chapel Hill, 1969)Google Scholar and Hofstadter, Richard, The idea of a party system: the rise of legitimate opposition in the United States, 1780–1840 (Berkeley, 1969)Google Scholar. On the withdrawal of the economic elite from politics see Mills, C. Wright, ‘The American business elite: a collective portrait’, Journal of Economic History, V (1945), supplement, pp. 36–8Google Scholar and Fischer, David H., The revolution of American conservatism: the Federalist party in the era of Jeffersonian democracy (New York, 1965), pp. 25–32.Google Scholar

- 2

- Cited by