The war veteran, man of letters, second-rank Bloomsburyite, prolific anti-fascist columnist, classical scholar, and crisis diarist F. L. (Peter) Lucas (1894–1967) captured a particular sense of bewilderment in the autumn of 1938: ‘The Crisis seems to have filled the world with nervous break-downs. Or perhaps the Crisis itself was only one more nervous break-down of a world driven by the killing pace of modern life and competition into ever acuter neurasthenia.’Footnote 1 How did it feel to live through the Munich Crisis and its fallout, and how did it feel to want to die because of the oppressive war fear, and spiralling levels of private and public anxiety? Private and individual experience mirrored the collective and public one, and as Virginia Woolf mused in mid-September 1938: ‘Odd this new public anxiety: how it compares with private: how it blinds.’Footnote 2 Her despondency deepening, the next day she confessed ‘it’s a hopeless war this – when we know winning means nothing. So we are committed, for the rest of our lives, to public misery. This will be slashed with private too.’Footnote 3 A couple of days later, Woolf diagnosed: ‘Just as in violent personal anxiety, the public lapses, into complete indifference. One can feel no more at the moment’, revealing the extent of her emotional exhaustion, and the conjuncture between a crisis of the self and nation.Footnote 4 In psychological terms, there was a universality of experience, and there was little that differentiated how the powerful and powerless endured the emotional cycle of the crisis, even if there was a stark polarity between the supporters and opponents of appeasement.

One of the dominant tropes to emerge in both the discursive framing and the lived experience of the international crisis was that this was a ‘war of nerves’, understood in psychological and physical, diplomatic and military, and metaphorical and imagistic terms. It was a fundamentally different kind of warfare. Never before

has there been a war of nerves such as this … Not bullets only, nor artillery, nor bayonets nor bombs dropping from the sky are the modern armoury; but threats of mysterious weapons, gigantic bluff, and a cat-and-mouse game intended to stampede the civilian population of this island into terror.Footnote 5

According to the practical psychologist H. Ernest Hunt, Hitler’s war of nerves was ‘like no other war that the world has yet seen, because it is being waged, as it were, simultaneously upon two battlefields, the mental and the physical’.Footnote 6 The leading British psychoanalyst and medical psychologist Edward Glover reflected on the extensive study of how his own psychiatric patients responded to the fear and fact of modern warfare, proceeding to project these diagnoses of individual pathologies onto British society as a whole. He ‘pointed out that the most serious cause of civil demoralization is not fear of real danger, which is sensible enough, but those vague panicky feelings that are due to “over-nervousness”’.Footnote 7Glover’s colleague W. H. Bion, a physician and psychiatrist associated with the Tavistock Clinic, emphasized that ‘the war of nerves’ ‘is nothing new as a fact of human experience; what is new is that its existence has been recognised under an almost medical title’.Footnote 8 Like Glover, Bion wrote for a wider readership, and he was one of the many popularizers of psychopathological analyses of the home front.Footnote 9

By reflecting on two bodies of evidence (and evidence of embodiment), this study contests and disrupts the traditional chorological markers of the accelerating international crisis and the descent into war in Britain, from the summer of 1938 to the spring of 1940. First, I listen to those voices who shared their personal experience of or displaced the overwhelming nervous strain of the crisis onto the nation as a whole, starting with F. L. Lucas, who was himself both witness and victim of the opening battles of the war of nerves. Second, based on a dataset of 185 cases, I consider compelling evidence of a war-fear-triggered suicide epidemic.Footnote 10 Indeed, the cultural impact of the crisis suicides was disproportionate to the number of people who took their lives in this way and under these circumstances. Therefore the method proposed here is qualitative, and it is to conduct a forensic psychological autopsy of the psychiatric causalities of the war of nerves.Footnote 11 Since Émile Durkheim, suicidologists have asserted that suicides and the rhetoric of suicide serve as a synecdoche for the interaction between private and social crisis, individual mental health and the condition of the body politic, and the psychological subject and society.Footnote 12 In exhuming these crisis suicides, I hope to confer dignity on those who ended their lives tragically under these conditions by acknowledging them as the casualties of this same war of nerves.Footnote 13 A wave of war-fear-triggered suicides was tangible evidence of the impact of the international crisis in the domestic sphere and on the home front.Footnote 14

I

Historians have consistently moved around the bookends of historical periods to offer fresh retellings of seemingly fixed national narratives.Footnote 15 The default chronological structure for the first half of the twentieth century is the two world wars, with the interwar years further subdivided by the Great Depression. In scholarship as in popular culture, the 1920s have been variously encapsulated as the ‘roaring twenties’, ‘the Jazz Age’, and the age of the flapper. The consequences of the Wall Street Crash undermined the alleged social optimism, cultural innovation, personal frivolity, and the promise of political and diplomatic post-war reconstruction. There was a sudden descent into the ‘hungry thirties’ (Paula Bartley), the ‘devil’s decade’ (Claude Cockburn), the ‘long weekend’ (Robert Graves and Alan Hodge), or even just ‘the thirties’ (Malcolm Muggeridge, Juliet Gardiner) that on its own has the power to evoke a state of socio-economic misery, perpetual crisis, and passionate political polarization.Footnote 16 With a dizzying mixture of nostalgia, disgust, and condescension, Muggeridge recognized how ‘men aim at projecting their own inward unease on to as large a screen as possible’. He opened his panoramic expedition through the decade by reminding readers how ‘one of the few constants in life … is a sense of crisis’, while admitting that ‘the decade just ended may legitimately be regarded as unusually eventful’.Footnote 17 As a unity, the years between the two world wars have been characterized as the ‘inter-war crisis’ (Overy), the ‘failure of political extremism’ (Thorpe), and the ‘morbid age’ (Overy), or, alternatively and as a reminder of the more mundane and quotidian alongside the socio-economic anguish of the Depression, as a period when ‘we danced all night’ (Pugh).Footnote 18 Likewise, Law has suggested that 1938 was the apex of ‘a modern society in development’, and Britons were far less obsessed by prophecies of war than has been suggested.Footnote 19

Sequestering the pivotal events of the late 1930s, the most commonly used collective epitaphs are the international crisis – the climax of which was the September Crisis, the Munich Crisis, or the ‘four days of crisis’ (25–29 September 1938),Footnote 20 or succinctly ‘the Crisis’ – the age of appeasement; the countdown to war; the Phoney War or the Bore War; and, finally, the first battles of the ‘People’s War’. Titmuss referred to the period from September 1939 to May 1940 as ‘the Phase of Uncertainty’, measuring the material and psychological strains on civilian morale.Footnote 21 Recently, two monumental tomes, Todman’s Britain’s war: into the battle, 1937–1941 and Allport’s Britain at bay: the epic story of the Second World War, 1938–1941, have each made persuasive cases to think in terms of a long 1930s or collapsing the last years of the decade into the Second World War itself.Footnote 22 Indeed, even more recently there has been a vigorous scholarly debate about the ‘People’s War’ branding: its etymology, its authorship, its actual prevalence at the time, and the post-war ideological weaponization of the reality or myth of national and imperial unity across class lines.Footnote 23 Taking our cue from these alternative horizon points – and giving due weight to intimate, discursive, popular, and socio-medical sources – we should recognize, as contemporaries did, that the prelude to the Blitz was a war of nerves.

Likewise, this study proposes taking a significant turn in the ever-plenteous historiography of appeasement. Since the publication of ‘Cato’s’ Guilty men (July 1940), the spiralling debate between revisionists, counter-revisionists, and post-revisionists about the strategic and moral failures or good intentions of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and the architects of British foreign policy has lost little momentum.Footnote 24 This literature tends to take an unreflectively top-down perspective. The same is true for representations in popular culture, such as Robert Harris’s novel Munich (2017) and the Netflix adaptation for the screen as Munich: the edge of war (2022). However, it bears emphasizing that the dramatic unfolding of the Sudeten Crisis, and the signing of both the Four Powers Agreement and the Anglo-German Declaration in Munich on 30 September 1938, was all-engrossing, irrespective of class, generation, gender, region, ethnicity, or political influence. Every aspect of the crisis dominated the news disseminated by the press, radio, and newsreels, intruding into every facet of people’s lives and their consciousness. The newspapers published ‘fever charts’ that claimed to measure surges in public feeling.Footnote 25 National and provincial papers covered the foreign news extensively and in ways accessible to their receptive demographic of readers, while simultaneously disseminating vital public service information about the distribution of gas masks, preparations for evacuation, ARP drills, enlistment and voluntary work, and warnings about hoarding. The consistent message was that the public needed to stay calm, and should leave hysterical displays to foreigners. Launched in early 1937, the social research project Mass-Observation was out in force to capture the reaction of the ‘man on the street’, and Mass-Observation volunteers were busier than ever writing up their directive replies. All this evidence was published within months, as Harrisson and Madge’s Penguin special Britain by Mass-Observation in January 1939. Similarly, private diaries kept by well-known names and anonymous writers alike were saturated by feelings about the hyperactive news cycle, confessing relief or shame, admiration or rage, and hope or dejection, or a confusing blend of all the above.

Encouragingly, the different turns in historical scholarship – cultural, gender, transnational, material, and emotional – have directed us to new evidence and long-suppressed points of view.Footnote 26 Indeed, the close study of public opinion and appeasement pulled the scholarship out of the familiar rut of great man/guilty man thinking, leaving the way clear for enquiries about private opinion and intimate experience of the Munich Crisis.Footnote 27 There is a deep intimate history, an internal and internalized history, of international relations. As Bourke argues, ‘emotions have to be made “visible” if historians are to examine them’.Footnote 28 Building on a rich seam of scholarship unearthing the war inside, the ‘domestic angst on the home front’,Footnote 29 and the pathologizing of the public sphere, this study will considers the ‘crisis inside’, and the interior history of the arguably more tense, anxious, and unpredictable pre-war.

II

How can we access and record the tangible and material, the ethereal and emotional, and the psychological and visceral experience of the international crisis? In fact, Frank Laurence (Peter) Lucas anticipated the interest that historians of the future would or rather should have with the cognitive aspect of political crisis. His Journal under the terror, 1938, in which he undertook to keep a diary from 31 December 1937 to 31 December 1938, provided an answer to the question he wanted future historians to ask: ‘What can it have felt like to live in that strange, tormented and demented world?’Footnote 30 He was a recognized public intellectual, prolific political commentator, and vocal critic of appeasement, but his diary nonetheless offers an emotionally expressive and expansive personal narrative.Footnote 31 Deliberately and self-consciously amassed, it stands as an affective archive of the crisis, ripe for a close reading. A classical scholar himself, Lucas ‘dearly’ wished ‘that some Roman of the crumbling Empire of Honorius or Valentinian had done so much for me, while he too watched the tides of barbarism lap higher and higher against the dykes of the civilized world’.Footnote 32 Had such a source existed for the Roman world as he was generating for the modern one, it would ‘not replace Gibbon; but how it would supplement him!’Footnote 33 Throughout the contrived public-facing diary form, Lucas is acutely aware that he is writing a history from the point of view of his present, and – employing the current Freudian vocabulary in which he was well versed – ponders: ‘What will historians make of this England of 1938? That, grown old in Empire, we had a secret death-wish and longed unconsciously to perish? Since at least there is peace in the grave.’Footnote 34 A decade earlier, H. G. Wells had suggested that theirs would be ‘a century of applied psychology’, and Lucas was one more intellectual who contributed to the ‘psychologization’ of his time.Footnote 35

The dominant emotions he experienced during the course of this year of hastening terror were ‘impotent anger’, guilt, sleeplessness ‘with dismay and shame’, psychic disturbances, cynicism and fatalism, and the descent into circumstantially triggered mental illness. The title of the diary itself, Journal under the terror, 1938, speaks to that vicarious British experience of fascism, as Lucas and his compatriots were not the victims of terror in any corporeal terms as in Spain, Germany, Abyssinia, Austria, or Czechoslovakia. This terror was at one remove; it was imagined and internalized. At the beginning of September, Lucas tries to diagnose the visceral rhythm of the crisis. He remarks on the seemingly contradictory responses of dread and excitement: ‘It is partly, I think, that a sense of crisis must make one’s glands respond by pouring energisers like adrenalin into one’s blood. But partly, too, that one fears a peace fouler and more fatal even than war.’Footnote 36 A few days later, on 4 September, he ponders the curious ‘psychological effects of prolonged crisis’.Footnote 37 The political crisis in which ‘Europe lets itself be kept on tenterhooks by one neurotic’,Footnote 38 dominates both his conscious and subconscious thought, and he records that

In the morning, when physically fresh, I feel a robust fatalism. In the afternoon, reading my regular six newspapers, growing rage and gloom. In the small hours, I wake as oppressed as if I had a sack of concrete on my chest. Bed, indeed, is always bad for my morale; lying on one’s back one feels, mentally also, as helpless as an overturned tortoise.Footnote 39

It would be little wonder if readers hear echoes of Lucas’s nervous state, and detect emotional parallels between then and the present era of polycrisis and permacrisis.Footnote 40

At every turn in the gripping September Crisis, Lucas documents the psycho-medical effects: nausea, depression, sickening feeling evoked by fear of a war on civilians, listening to the radio on 30 September and feeling ‘physically sick’. In contrast, Neville Chamberlain is depicted as Dr Faustus, as a trout-fishing Pontius Pilate, and as ‘that elderly incubus’ who is ‘intoxicated with nervous reaction’.Footnote 41 In Lucas’s opinion, the prime minister is feasting on the approbation of the ‘hysterical mob of London’ and the ‘hysterical cheering of Cockney cads’.Footnote 42 Lucas does, however, experience unexpected symptoms, offering as a self-assessment that ‘the Crisis must have somehow stimulated my adrenal glands to pour extra adrenalin into my blood or something: for never have I felt fuller of energy and a desperate gaiety than through these gloomy weeks’.Footnote 43 This madness is collective, and Lucas speaks of a world ‘threatened with an epidemic of nervous breakdowns’ and the ‘general spread of neuroticism’.Footnote 44 Susan Kingsley Kent’s compelling alternative periodization in her study Aftershocks: politics and trauma in Britain, 1918–1931 (2009) could be extended easily to 1938–9. Lucas is very receptive to psycho-history as a means of answering the questions that Marxist economics cannot, thinking of ways in which to chart ‘more fundamental fluctuations in the general mentality, by epidemics of neurasthenia’.Footnote 45 He is engrossed in the contemplation of his own mortality and fully aware that, under the terror, suicide – deemed a morally and psychically legitimate way out – is on everyone’s mind:

Heaven knows modern Europe is no place to live without a safety-exit. I often think it not the least of the virtues of a car that the fumes of its exhaust will convey one so smoothly down to the shores of the Styx … Morbid? But this is what a good many of us were thinking in 1938.Footnote 46

To corroborate Overy’s sweeping overview of the period, this was a ‘morbid age’ indeed, and suicide – actual and ideational – was a particularly revealing individuated expression of and pathological response to the international crisis.

For Lucas, 1938 was also a personal annus horribilis. The collective descent into madness coincided with the mental breakdown of his second wife, Prudence née Wilkinson (1911–44). His diary records his steady immersion into fatalism and his feeling that ‘to talk of old age in 1938 is indeed meeting trouble half-way. Who knows if the world will last three years?’,Footnote 47 while he watches his wife suffer a serious breakdown, with the implication that external conditions have been a trigger. In fact, Prudence was unable to attend the opening night of his play The lovers of Gudrun at the Stockport Garrick Theatre, a play for which she designed the set and costumes, because she was hospitalized. Incidentally, the first night of the play was 10 November, Kristallnacht (the November Pogrom). Lucas notes, ‘The Crisis seems to have filled the world with nervous break-downs’, before revealing that ‘now it has happened at my own hearth. Nothing ghastlier than to see the person one has known best in the world for seven years turn into an unknown who no longer knows herself.’Footnote 48 He protects his wife’s privacy to some extent, never identifying her as more than ‘P’ in the text, offering no character description, and giving few details of her medical condition and its symptoms.

Instead, Lucas documents his own response to her declining mental health: he is ‘wretched, numbed, paralysed with depression’.Footnote 49 As he tries to care for her he now has a new understanding and insight into Shakespeare’s tragic heroines Ophelia and Lady Macbeth. Prudence’s breakdown would eventually lead to the breakdown of the marriage, foreshadowed in his diary entry of 14 November: ‘The horror of nervous break-downs is the way in which the person dearest hitherto becomes the most hateful to this new personality, this changeling, this sick usurper that has become dictator in the stricken brain.’Footnote 50 Her mental crisis inevitably sidetracked his diary project, as ‘the illness of someone one loves blots out the Universe’.Footnote 51

Lucas’s diary consists of repeated ruminations on his own war service and the formative experience of his missing generation, but he could not countenance pacifism. His is a militant anti-fascism, with near certainty that war is coming, and that it is justified and inevitable.Footnote 52 And yet, for a pregnant moment, he finds himself reassessing his firm anti-appeasement stance and activist anti-fascism because of his personal experience,Footnote 53 and thinking ‘God, if there’s a war, it’ll wreck her [Prudence’s] treatment. The Crisis of last September was nothing to this.’Footnote 54 His experience of living through and alongside mental illness was to change the way that Lucas understood historical forces. He turned to the work of the Austrian psychoanalyst Wilhelm Stekel (who, incidentally, as a refugee in Britain, committed suicide in 1940 and is one among the 185 cases in the dataset), concluding that ‘the fundamental evil of the world to-day does not lie in economic or political problems … the evil lies in the human brain. Not merely in its stupidity; still more in its neuroses – its sadism and masochism, its possessiveness and aggressiveness, its endless phobias.’Footnote 55

Lucas’s year-long diary project ends in a very different place from where it began. This was not merely because of the ever more acute political crisis – which he had foreseen in the very act of keeping this diary – but as the result of his personal unhappiness and the calamity of his wife’s mental illness: ‘for ten months of the year I was strangely happy, even under the shadow of imminent war. Then suddenly my own world burst like a bubble, for reasons neither king nor dictator could cause nor cure.’Footnote 56 And yet the Lucases’ troubles were only one example of the lives that had been disordered in those crisis months in the circle of Virginia Woolf. On 28 February 1939, Woolf recorded a luncheon conversation: ‘Much argument: communism defined … also gossip about Peter & Prudence [Lucas]; she mad.’Footnote 57

It has taken longer than Lucas might have expected for historians of appeasement to frame their inquiries in these terms, or to recognize the value of this kind of ‘supplementary’ material to nuance or perhaps even to start to destabilize the ‘official’ history. However, this is precisely what needs to be done. Lucas is one of the many narrators, hitherto almost forgotten by historians, of the ‘war of nerves’.

III

The last crisis-ridden years and months of the peace were a war of nerves. Before the declaration of war, according to Ellis, ‘We have about a year therefore of the “war of nerves”, stimulated not simply by events abroad but, of course, by the domestic planning for war that was stepped up from March onwards.’ This phase can be ‘seen as having to some degree a unitary character in the peculiar emotions and responses resulting from the war of nerves, a period in which, in Orwell’s phrase, “the peace that is not a peace slumps into a war that is not a war”’.Footnote 58

As I argue, however, the opening battle of this war of nerves was the Munich Crisis, and its last throes were in the spring of 1940, with the German invasion of Holland and Belgium. This was a war of nerves on multiple levels – diplomatic, morale, private, and even commercial. We see both the recycling of the terminology of the First World War, and the repurposing of this language to reflect the greater sophistication and menace of Nazi psyops and the apocalyptic possibilities of cutting-edge war technologies. The strategizing, trickery, and behaviour under pressure of politicians, diplomats, and propaganda chiefs were likened to an agonizing waiting game, a high-stakes card game, and gambling with the fate of the peoples of Europe. Hitler’s and Goebbels’s modern techniques of psychological warfare, of wearing down the enemy by keeping them guessing about their next belligerent move, was termed the ‘war of nerves’. By the spring of 1939, this phrase was specifically applied to the Free City of Danzig as the Nazis demanded its incorporation into the Reich. The Daily Mail employed this terminology extensively, and always to stress British resolve and strength when confronted by the dictators’ brand of undiplomatic bullying. In Lord Rothermere’s characteristic rhetoric of nationalist bravado, the Mail reported on the failed German coup of Danzig, and noted the continuity between Nazi propaganda techniques from the Sudeten Crisis to the current one: ‘The provocations, the propaganda, the movements of troops, the storming of the citadel from within … But the British people are not easy targets for the snipers of Dr Goebbels. We should win in a war of guns. We shall certainly not be defeated in a war of nerves.’Footnote 59 Anthony Eden used the term in a letter to his constituents at the beginning of August 1939, as he braced them for war, while still holding out hope for peace by convincing ‘the rulers and peoples of Germany and Italy of the unshakable firmness of our determination’.Footnote 60 Winston Churchill both used the term ‘the war of nerves’ to describe the Nazi attempt to wear down the democracies, and also coined the phrase ‘this bloodless war’ to describe the limbo in the months before the declaration of war.Footnote 61

The British imagined themselves to have a nationally specific response to the war of nerves. On the one hand, the nation was better equipped to deal with the overblown emotionality of totalitarian propaganda due to stereotypical features of British reserve, keeping one’s nerve, and emotional economy.Footnote 62 This is well exemplified by the language used by Oliver Stanley, president of the Board of Trade, when he addressed his constituents in Westmorland in the summer of 1939 on what it meant to be living through a war of nerves:

Part of it is quite deliberate, and is intended to keep the world in a state of nervous tension, in the belief that it will sap the people of determination and destroy their courage, so that others will be able to profit from their spinelessness. It is up to the people of this country to show other countries that this war of nerves is going to have no effect upon us. … Let the old British calm go on, for in that calm we can have confidence in our own strength and confidence in our own cause.Footnote 63

There were just as many signs of the fraying of nerves, countless cases of the jitters, and concerns about the threat to British resolve posed by ‘jitterbugs’ (a sanitized and more comic diagnosis of anxiety). Advertisers and anti-appeasers alike found the analogy highly profitable. For instance, the ‘brain tonic’ and ‘nerve revitaliser’ Sanatogen came up with the slogan that imbibing their product was ‘How to win your “war of nerves”’, and ran a whole campaign with this banner from 1938 to 1940.Footnote 64 A similar product, Cheshire’s Adult Nerve Tonic, was advertised with the slogan ‘War nerves can be prevented … get a bottle today and build your nerves up to meet the strain’.Footnote 65 In another example of this exploitation of the commercial potential of the war of nerves, women were reported to be taking what we would today call retail therapy; in the week before war was declared, the sale of hats had increased, as ‘it is amazing just what a new hat does to a woman. While she is trying on some smart little model she forgets that such places as Danzig and the Polish Corridor exist.’Footnote 66 Similarly, Wrigley’s chewing gum was advertised with the slogan ‘Feeling nervy? Wrigley’s will sooth you’, and Steero Bouillon Cubes used the slogan ‘Invites rest – relaxes nerves’.Footnote 67 Franklyn’s Wild Tobacco promised smokers how ‘at moments of crisis a smoke soothes the nerves’.Footnote 68 Indeed, one could not ‘fail to notice the increase in nerve cure advertisements the war has brought out’.Footnote 69 While men too suffered from crisis-triggered anxiety, cures for nervous debilities predominantly targeted women consumers, consistent with the newly diagnosed condition of ‘suburban neurosis’ suffered by housewives. Even more specific to the war of nerves was the appearance of ‘crisis throat’.Footnote 70 All the remedies on the market to treat socially and environmentally caused conditions such as neurasthenia, stomach upset (acid reflux), and cases of the nerves offer a social aetiology of the war of nerves.

The emotionally transformative impact and indelible memory of the Munich Crisis was reinforced by the way it unfolded like a tragic-heroic drama, its theatricality and Shakespearian qualities scripted by the protagonists themselves. As he boarded the plane at Heston airport en route to Munich, Chamberlain quoted Hotspur in Henry V, ‘Out of this nettle, danger, we pluck this flower, safety.’ He explained the driving spirit behind his determined attempts to broker peace with his childhood mantra ‘If at first you don’t succeed, try, try, try again’. In a letter to his sister Hilda on 2 October, Chamberlain admitted that the last 48 hours had entailed ‘terrific physical and mental exertions’, due to the high drama and suspense of his negotiations with Hitler, especially when ‘the news of the deliverance should come to me in the very act of closing my speech in the House as a piece of drama that no work of fiction ever surpassed’.Footnote 71 Chamberlain’s own heart-racing experience of the build-up to the Munich Conference was experienced by millions in similarly emotive, visceral, and anxious terms. The international crisis was a trigger for countless emotional crises, and we have to make sure we use the term ‘crisis’ in a more expansive way and inclusive way – not merely in terms of a unique political emergency.

The Munich Crisis was just that: a national crisis, a crisis of the nation and of citizens. In their 1939 publication Britain by Mass-Observation, Tom Harrisson and Charles Madge were trying to define what ‘crisis’ meant: its etymology as well as its psychological symptoms. Mass-Observation considered it their brief to ‘follow the contest’ of the ‘war of nerves’. They diagnosed an increasing occurrence of ‘crisis fatigue’, fatalism, and apathy in response to the ‘sense of continuous crisis’, as well as a surge in ‘suicide talk’ that they interpreted as ‘the last stage in the collapse of belief in any future’.Footnote 72

IV

The crisis was a national one, to be sure, but it also had very private and personal ramifications, and one of the very saddest patterns to detect is a rise in the rate, and certainly of the press coverage, of suicides.Footnote 73 Overall, the suicide rate dipped during both world wars, and the highest peak in suicides was during the Great Depression, when mass unemployment and socio-economic hardship were seen to account for an epidemic of politically triggered suicides.Footnote 74 However, there was a slight increase in the suicide rate again in 1938. The death rates for men in the upper age categories descended to a low point in 1924, peaked in 1932, and then reached a secondary peak in 1938, before falling during the Second World War.Footnote 75 The gross figure for 1938 was 5,201 (3,490 males and 1,720 females) who died by suicide, either felo de se (self-murder) or ‘other cases of suicide’.Footnote 76 The figures for succeeding years were 5,021 for 1939, 4,822 for 1940, and 4,123 for 1941.Footnote 77 While the number of suicides was higher in 1938, this figure is cumulative, and due to a wide range of putative causes, from physical and mental illness, romantic disappointment, financial worries, and so on.

Looking at suicide rates is one way of mapping deteriorating mental health, but my interest in these cases is qualitative and discursive (anecdotal). I focus on those cases I have termed the ‘crisis suicides’: namely cases where evidence presented at the coroner’s inquest, by relatives, friends, doctors, or police, cited the victim’s negative reaction to the international crisis and fear of war and, implicitly or more often explicitly, testified that it was a catalyst. What could be a more decisive resolution to the war of nerves than suicide, a self-willed final exit and release from the intolerable fear and the phobia of modern war? Further, these individual cases of suicide were understood as symptomatic of a mass frenzy and hysteria, caused by the projection of disordered minds onto the nation and onto the relationships between nations. Again and again, we come across analyses of dictators hell bent on projecting their insanity on the European scene, and recasting Europe in the image of their unbalanced minds.Footnote 78 Analysing the annual report of the Board of Control on Lunacy and Mental Deficiency, a Spectator reporter reckoned that: ‘At the present time, indeed, there is often a legitimate doubt whether some of the leading actors on the world’s political stage would not be more at home in some institution where their aberrations would receive sympathetic attention and to a world often described in terms of the madhouse.’ It was clear to the reporter that ‘in a period of immense political and social strain, of wars and revolutions, actual or threatened, it is natural to suppose that the number of mental breakdowns would increase. National Socialists always pointed to the number of suicides as a proof of the demoralisation of the Weimar Republic.’Footnote 79 Nor was it only the dictators who were believed to be mentally ill; Cockburn said of the ‘Chamberlain group in Cabinet’ that they ‘were suffering from some morbid, collective paranoia, seemingly nearly pathological in character’.Footnote 80 As we have seen, the terminologies, therapeutic practices, and diagnostic techniques of psychoanalysis were steadily seeping into political discourse, while psychoanalysts increasingly put forward their analyses of the public sphere.

Furthermore, the persecution of Jews and political dissidents in Germany from 1933, the Anschluss, the Nazi occupation of the Sudetenland, Kristallnacht, and the Nazi seizure of the rump of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 were each direct and incontrovertible causes of a suicide pandemic. Covered extensively in the British press, reports of prominent individuals and massed hundreds or even thousands who took their lives as the last resort of evading their Nazi persecutors no doubt raised both levels of awareness of the war to come and anxiety about its nature. Lucas was deeply moved by reports of 800 suicides a month in Vienna, and the systematic humiliation of Austrian Jews by the Nazis, while the Daily Mirror described Vienna as ‘Suicide City’.Footnote 81 Even the Daily Mail, with its well-earned reputation for defending the dictators, reported the chief rabbi’s melancholy observation for the Jewish New Year 5699 of ‘a further catastrophic decline in human values and an appalling disregard of civilised standards’, a typical instance being that ‘during the month of August 250 Jews were shot, flogged to death or hounded to suicide in one concentration camp alone’.Footnote 82 Reporters expressed only compassion for ‘these agonised self-releases’ by scores of Austrians on the German blacklist.Footnote 83 Arguably, readers would have identified with these tragic cases, and we can only infer what impact such news items had on those who were themselves of nervous disposition and susceptible to suicidal impulses. There is apparent proof of this in the case of thirty-year-old Albert Ward who died by suicide, as next to his body lay ‘a newspaper containing a list of suicides’.Footnote 84

A recurring detail in many of the narratives of the crisis suicides was how reading the papers or listening to the BBC news on the wireless directly precipitated their act.Footnote 85 This was not a concern unique to the war of nerves, and throughout the period there had been unease voiced about the reporting of domestic suicide cases, and the press was severely criticized for feeding and fuelling the public’s morbid curiosity with graphic suicide stories. In 1936, a Home Office departmental committee report made a series of recommendations about the role of coroners, including ‘Press reports of inquests on suicides should be severely curtailed and put on a footing with reports of divorce cases.’Footnote 86 It is not at all clear that the press acted on this recommendation. In his 1938 study of suicide, Henry Romilly Fedden observed how the popular press had sensationalized suicide so that ‘one’s sole approach is now via the gas ovens of the Sunday Press’.Footnote 87

There are many instances where the concept of suicide was used in political discourse and as an analogy and a metaphor, in the sense of political suicide, national suicide, or race suicide. However, what concerns us now is how the crisis made people feel suicidal, or at least ready to make threats to that effect.Footnote 88 The New Statesman editor Kingsley Martin issued such menaces between mouthfuls at lunch with the Woolfs at the end of August 1938. As Virginia Woolf recalled: ‘Anyhow he [Martin] doesn’t want a European war now … If theres [sic] a war, “my own solution is suicidal” [she quotes him as saying] – while he munches mutton chops, & sweeps up fragments, scraping his knife & fork round the way I hate.’Footnote 89 Arguably, Woolf’s own suicide is one of the most famous of the period, and it has been the subject of numerous psychological autopsies. There is consensus that she took her own life in the midst of a manic-depressive episode, although her despair and quite rational fears of an invasion – as the wife of a Jew, and as a feminist, pacifist, and anti-fascist – were contributing factors.Footnote 90 However, as she died by suicide on 28 March 1941, her case is just beyond the scope of the ‘crisis suicides’ considered here.

Another Bloomsburyite, and a friend and fellow Cambridge Kingsman of Peter Lucas, E. M. Forster, in his essay ‘Post-Munich’, recognized the sharp rise in suicidal thinking and in actual acts of self-murder as incontrovertible evidence of the emotional fallout of the crisis. During the September Crisis, he noted how ‘exalted in contrary directions, some of us rose above ourselves, and others committed suicide’. Once Chamberlain’s policy had been proved bankrupt, politically impotent but thinking and feeling people found themselves in ‘mixed states [that] are terrible for nerves … Sensitive people are having a terrible time just now … If they could sell themselves, they would find peace; they could, on the other hand, go out hammer and tongs for National Service, pacifism, suicide etc.’Footnote 91 Indeed, the national and personal suicide impulse could be conflated, as in the Mass-Observer P. N. Herbert’s day survey:

The man in the street dread[s] [war], yet seems powerless to stop it. Women dread it even more, and many have told me that they will commit suicide rather than face another war, but they do nothing to prevent it … Yes; this recent crisis of ours has lowered our prestige abroad even more, and has enabled Western civilisation to take one more blind step on the path to suicide.Footnote 92

Miss Edith M. E. Oakley, a thirty-five-year-old foreign correspondent, gave this response to Mass-Observation’s question ‘What would you do in the event of war?’: ‘There is a common belief that the next war will involve attacks upon the civil population – air raids, gas, bombardments, etc. That would terrify me, and I should seek escape to the desolate regions of the Scottish Highlands, commit suicide or go mad.’Footnote 93 The suicidal impulse and a death wish spread like a contagion, according to the communist propagandist Claud Cockburn. He claimed it was the common belief at that time that ‘75 per cent of living beings, would be wiped out within six weeks, six days or six hours’ of the outbreak of a gas war. He noted that there were ‘pathologically suicidal types in whom the death-wish existed in the literal sense’, but even for the ‘normal people’ this death wish

lurked, consciously or unconsciously, as a form of relief: relief that all the botherations [sic] and uncertainties, the argument and strife, the worry, worry, worry of the past years in which those damned international politics had come barging into the living-room, the kitchen and the bedroom, would at least be abruptly ended and superseded by restful oblivion.Footnote 94

It is to these ‘pathologically suicidal types’ that we now turn, in an effort to recover the experience of a marginalized community, namely those suffering from mental illness, who are too often written out of history.

V

The correlation between mental illness, personal desperation, and national crisis was diagnosed and constructed by clinicians and coroners, by academics and artists, by politicians and pundits, by the media, and by suicides themselves. I have collected a dataset of 185 ‘crisis suicides’ that fit the following three criteria. First, the suicide had to have occurred between summer 1938 and spring 1940, during the war of nerves. Second, evidence by key witnesses, or in a suicide note, had to have testified to the pivotal role the international crisis had on the individual’s decision to take their own life. Third, the narration of the case – by witnesses, coroner, or the news media – had to have imposed a socio-political interpretation; emphasized the environmental triggers; read political meaning into the suicide method (for example, repurposing a gas mask to suffocate); and/or suggested that the case in question was one of a concatenation, and one of a group of victims of the rising temperature of the war of nerves.

The sensation value of binding crisis suicides together was not lost on newspaper editors, and headline writers used such phrases as ‘Three suicides from war fear’ or ‘Two “worry” suicides’.Footnote 95 The Daily Mirror’s columnist ‘Cassandra’ reported: ‘I’m told that ten people committed suicide because of the threat of war last week.’Footnote 96 Under the heart-wrenching headline ‘Peace came too late for these …’, the Birmingham Gazette told the story of three separate cases: one who took their life because they were ‘utterly down through war threat’, a second because the crisis was an ‘absolute nightmare’, and the third because they could not ‘face war again’.Footnote 97 Even more striking was that the Spanish press deemed the accumulation of suicides in Britain an epidemic, La Vanguardia reporting from London:

A symptom of the public’s grave distress, created by the artificial alarmism propagated by the radio and press, can be seen in the number of suicides which are committed daily by people terrorized at the thought of a war. … For foreign observers, these suicides in a country which rules over a third of the world, provoked at the mere suggestion of an eventual war, are a sign, which combined with current concerns amongst the British public over compulsory conscription, give cause for thought to the leaders of a country which declares itself the protector of all – Efe.Footnote 98

It was the type of story relished by foreign enemies, and was read as a sign of Britain’s effeminacy and decline. Indeed, Mussolini asserted that ‘The Fascist accepts life and loves it, knowing nothing of and despising suicide: he rather conceives of life as duty and struggle and conquest, life which should be high and full, lived for oneself but above all for others.’Footnote 99 It suited fascists to see suicide as symptomatic of the liberal and democratic cult of individualism.

In the main, these suicide cases were initially identified by research in newspapers – local, regional, national, and international; when possible, the leads were followed up in coroners’ archives (although the preservation of coroners’ records is very patchy). I have relied heavily on the mining of newspaper sources mainly because so few of the coroners’ inquest records for these cases have exist.Footnote 100 From the nineteenth century onwards, newspaper reports are usually the only surviving accounts of unexpected, sudden, or suspicious deaths.Footnote 101 There are some exceptions, and I have been able to locate a handful of relevant coroner inquest case files. What these fuller records provide is added detail – much of it procedural – but they do not tend to reveal otherwise hidden depths. For instance, in the inquest into the death of Irene Lizzie Howard, the deceased’s sister clarified the impact the crisis had had on her. Margaret Howard testified:

She seemed worried on Sunday the 30 October 1938 and was more quiet than usual … worried over the recent crisis and … that affected her. Her brother was killed during the last war and my mother died the same day … never known her to threaten to take her life.Footnote 102

The files on the case of Dame Helena Swanwick in the Berkshire Record Office reveals some doubt whether her death was suicide or from natural causes, with fine forensic detail about her physical condition, and inclusion of the letters she left to confirm her intent and settle her affairs.Footnote 103 The newspaper reports, on the other hand, impose the socio-cultural meaning of this notional epidemic of ‘crisis suicides’ in Britain.

Most strikingly, the reports of coroners’ inquests demonstrated that all parties treated these suicide cases with understanding and sympathy. Before the passage of the Suicide Act 1961, suicide was a felonious act akin to murder. However, by the 1930s, the verdict of felo de se was rarely passed, and in all 185 cases under scrutiny here the coroner’s verdict was suicide ‘while the balance of mind was disturbed’, as this was not a felony. In contrast, a verdict of felo de se led to forfeiture of the victim’s life insurance policy and denied him or her a prayer book burial.Footnote 104 There is little sense of blaming or shaming these victims of their own hand. Compassion and empathy for the pressures imposed by the international emergency and the spectre of a gas and aerial war eclipsed moral, religious, or legal considerations and judgements. In many of these cases, we also see rigid constructions of war-willing masculinity disturbed, and equally inflexible expectations of feminine protective instinct and self-sacrifice challenged. These shifting attitudes were part of longer-term trends linked to clinical and popular understanding of shell shock, and the mainstreaming of medical psychology and psychoanalysis.Footnote 105 This is illustrated by an article in the Yorkshire Post that referred to the ‘emotional casualties’ of the Munich Crisis, and, although readers would no doubt have been breathing a ‘great sigh of relief’ that war had been averted at Munich, there was still need to ‘attend our casualties in this emotional upheaval’.Footnote 106 Further, trusting the prognosis of psychiatrists, the state was gearing up for a war on civilians, a war in which ‘psychiatric casualties might exceed physical casualties by three to one’.Footnote 107 In the final reckoning there was, in fact, ‘the absence of an increase in neurotic illness among the civilian population during the war’, because, as Titmuss has famously argued, war ‘brought useful work and an opportunity to play an active part within the community’.Footnote 108 Without the benefit of hindsight, however, in its coverage of the crisis suicides the press was mirroring and magnifying individual experiences of the war of nerves.Footnote 109

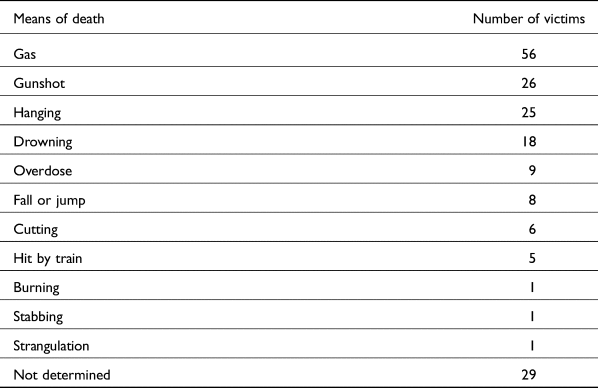

From A to Z, the ‘crisis suicides’ range over a wide geography, from Ambleside to York. In terms of occupation, they range from ARP volunteer to works director. Of the cohort, 75 are female and 110 male. In terms of marital status, 101 were married, 25 single, and 12 widowed; in the other cases marital status was not disclosed. We know that at least sixty of the cohort had children. The vast majority were British, but the total includes six Germans, two naturalized British, one South African, and four Austrians. Religion was rarely disclosed unless the suicide was not Christian, and in the group there were eight who were explicitly identified as or quite obviously Jewish. The method of death is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Means of death in the ‘crisis suicides’ of 1930–40

While the vast majority of this cohort are ordinary people and they would not have appeared in the public record but for the nature of their death, there are a few public figures in the group, including Col. Anthony Muirhead, MP for Wells (d. 29 October 1939), and the suffragist-internationalist writer Helena Swanwick (d. 16 November 1939). The Kent-based novelist and short-story writer Mrs Elizabeth Winch (penname Evelyn Winch), who was well known in her lifetime, took her life after ‘the September Crisis had upset her and she was also obsessed by an extraordinary fear that her little girl was going to be taken away from her’.Footnote 110 Winch’s story was one of the most widely reported, a compelling human-interest account that wove together the timely themes of nervous disorder, fear of war, and heightened maternal instinct. Perhaps it was morbid voyeurism that explains why Swanwick’s, Muirhead’s, and Winch’s stories were each reported in multiple newspapers, as, indeed, the majority of the 185 stories were syndicated across the national and provincial press. In fact, there were other celebrity crisis suicides that received publicity, such as those of Ernst Toller and Walter Benjamin, but they are not included because they occurred outside Britain.

The coroners’ inquests disclosed that many of these 185 people suffered from pre-existing mental illness, usually described as some form of nervous disorder or neurasthenia, while others made very reasoned and rational cases for their actions.Footnote 111 In many examples, we have a sense of their frame of mind from the note they left, while in others their motives can only be inferred from the testimony of witnesses and their loved ones.

The unifying characteristic of these suicide cases was fear of what was to come, and refusal to live through another war. For example, ‘Fear that there might soon be another European war was the reason given at a Hammersmith (London) inquest for the suicide of John James Macdonald, a 42 years old fitters’ engineer … who gassed himself at his home.’Footnote 112 He had served in the navy in ‘mystery’ ships during the Great War. Alice May Gibbons, age twenty-six, of South Harting, who had lived in Germany and was worried by the crisis, fell to her death from a hotel window soon after returning from a dance, with an open verdict returned.Footnote 113 A railwayman’s suicide was ‘blamed on the European crisis’.Footnote 114 Harriet Edge, aged sixty-three, was ‘depressed by the war and “what might be coming” in the way of air raids’, and she ‘put her head in the gas oven’. Edge’s husband, a sheet metal worker, told the coroner that ‘she has been under medical care for nervous debility’.Footnote 115 A Bournemouth doctor killed himself because he had ‘been depressed since the crisis’ and ‘his mind had been unbalanced owing to the possibility of war’.Footnote 116 Similarly, at another inquest in Bournemouth, ‘worry over his foreign investments’ was stated to have caused Dr Claude Burgoyne Pasley, age sixty-one, to take his life. Wearing only pyjamas, Dr Pasley was found drowned in the River Stour a few miles from his home. ‘He had been depressed since the crisis because of his fears of war.’Footnote 117 At the inquest into the death of Charles Orton, aged forty-nine, it was stated that he took his life because of fear that his two sons might ‘“have to go and fight” and as a result of the war-scare caused by the international situation’ – he used a razor blade.Footnote 118 The husband of Mrs Margaret Ann Wakefield of Croydon told the inquest into her death that she ‘has suffered with her nerves for several years, has fits of depression and slept badly. She was obsessed with fear of war and talked about it a great deal. She did not like the idea of gas masks.’Footnote 119 Mrs Wakefield put her head in the gas oven. A Cheltenham woman’s suicide was attributed to her ‘worry over the international situation’.Footnote 120

Some variation of the above hypotheses of causation was articulated in nearly all of these 185 cases. However, what does stand out as unique to this epidemic is one of the recurrent suicide methods: suicide by gas poisoning and even by gas mask. On the one hand, suicide by gas poisoning had been steadily on the increase over the preceding three decades,Footnote 121 and, as such, we should not be surprised by the frequency of this suicide method, especially in the home and by women who put an end to it all by putting their heads in the oven, in what was, after all, that not so liberating room of their own, the kitchen. On the other hand, the greater access to gas appliances, and the publicity surrounding cases of suicide by gas poisoning, meant that this was coming to be the most employed suicide method by 1938.

Aside from the preponderance of cases in which gas, fear of gas war, or the spectre of the gas mask figured, even more poignant are the cases where the gas mask was repurposed as the tool to take one’s life. The instrumentalization of the gas mask as suicide method was the precise inversion of its intended function. It was tragically poetic that a mechanism to prevent death was transformed into the instrument of self-inflicted death. There is a real blurring of boundaries between end and means here, although it is never clear if the suicide himself – and, strikingly, most cases in this category are male – intended to make the point we might read into the event.

With deeply symbolic resonance that was clearly not lost on the press that reported the stories, the gas mask became the device of suicide in the case of the Surrey man Arthur Cruttenden, aged fifty-three and unemployed. He fixed some gas tubing he had inserted into his civilian gas mask, and then turned on the gas. He was found dead by his wife.Footnote 122 Suicide while the balance of his mind was temporarily disturbed was the verdict reached in the case of George Nicoll, a South African jockey ‘who was found dead at his house in Newmarket wearing a gas-mask. A rubber tube extended from inside the mask to a gas pipe near him.’Footnote 123 An unemployed stage and television actor, Patrick Montgomery Gower, aged thirty-four, gassed himself with the aid of a civilian gas mask in his flatlet in Notting Hill.Footnote 124 Mr Ronald Sinclair Watson, a Cheltenham-based dress reformer, aged sixty-three, took his own life by inhaling coal gas, making meticulous preparations that the ‘room in which he proposed to die would be gas proof, even to Air Raid Precautions sealing tape for the door and windows’.Footnote 125 In all these cases, material preparation for war – the arming of civilians with the tools and weapons of self-defence against gas attack – is subverted, and these objects of conflict become objects of inner conflict. They are the weapons and the arsenal of the war of nerves. In one sense, we can interpret these crisis-triggered suicides as acts of self-defence. Exercising free will, each person made the fateful choice to harness the destructive power of modern petrochemicals to commit an act of self-destruction, rather than await the uncertain timing but certain carnage of war from the air.

While these 185 individuals had little in common and no obvious connections with one another in life, they become a group in death, and specifically in the manner of their deaths. The work of excavating these cases is emotionally challenging, but also carries with it a sense of duty and urgency. By telling their stories we do not sensationalize their pain but can instead confer some form of dignity on the dead, recognize their suffering, and feel even more sympathy for them now as the forgotten casualties of the devastating war of nerves.

VI

In conclusion, the profound emotional impact, the psychological consequences (both personal and universal), and the repeated discursive markers of nervous disorder and national suicide are striking in the context of this period. Starting with the Munich Crisis, the long months of extreme apprehension and the longer months from crisis through to the close of the Phoney War were most vividly described as the ‘war of nerves’ and that ‘fear-haunted twilight zone between war and peace’.Footnote 126 While perhaps uniquely insightful and poetic in observing how the ‘Crisis seems to have filled the world with nervous break-downs’, F. L. Lucas and his wife Prudence’s internalization of the looming war was hardly an uncommon response. A collective state of suspenseful high anxiety was inevitably experienced as personal crisis too, evidenced by the rise in the occurrence of suicide motivated by war fear and the accompanying press coverage. The Munich Crisis even provided a new method for madness: the number of suicides committed with government-issued gas masks. Paradoxically, fear of the next world war was intensified by the cataclysmic potential of the new technologies of killing, especially aerial bombardment and gas attack, and yet the inhalation of household gas was the fastest growing suicide method.Footnote 127

Sociologists try to understand why suicides happen by conducting psychological autopsies and social autopsies of individual cases and groups of cases. As I have argued here, we can reflect on the evidence of the ‘war of nerves’ and the crisis suicides to provide some form of political autopsy of the period. Further, the focus on mental health and emotional crisis invites us to challenge existing periodization, shifting the signposts marking political and military events to the emotional repercussions of the peaks and troughs of war fear. Overall, rescuing the experiences of those most deeply affected by the war of nerves allows for the elucidation of the relationship between bodily and national crisis in the ‘morbid age’, enriching our understanding of the mental landscape and the impact of two world wars on society and the self in modern Britain.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Adrian Bingham, Caoimhe Nic Dháibhéid, Matthew Stibbe, and Richard Toye for their support and insightful feedback on earlier iterations of this article; the thoughtful critiques offered by the Historical Journal’s editors and anonymous reviewers; and the inspired research assistance of Stephanie Wright, Hannah Parker, and Ryosuke Yokoe.

Funding statement

The initial research for this study was conducted with the generous support of a Wellcome Seed Award (2018–19) on ‘Suicide, society and crisis’, award no. 205356/Z/16/Z.

Competing interests

The author declares none.