No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

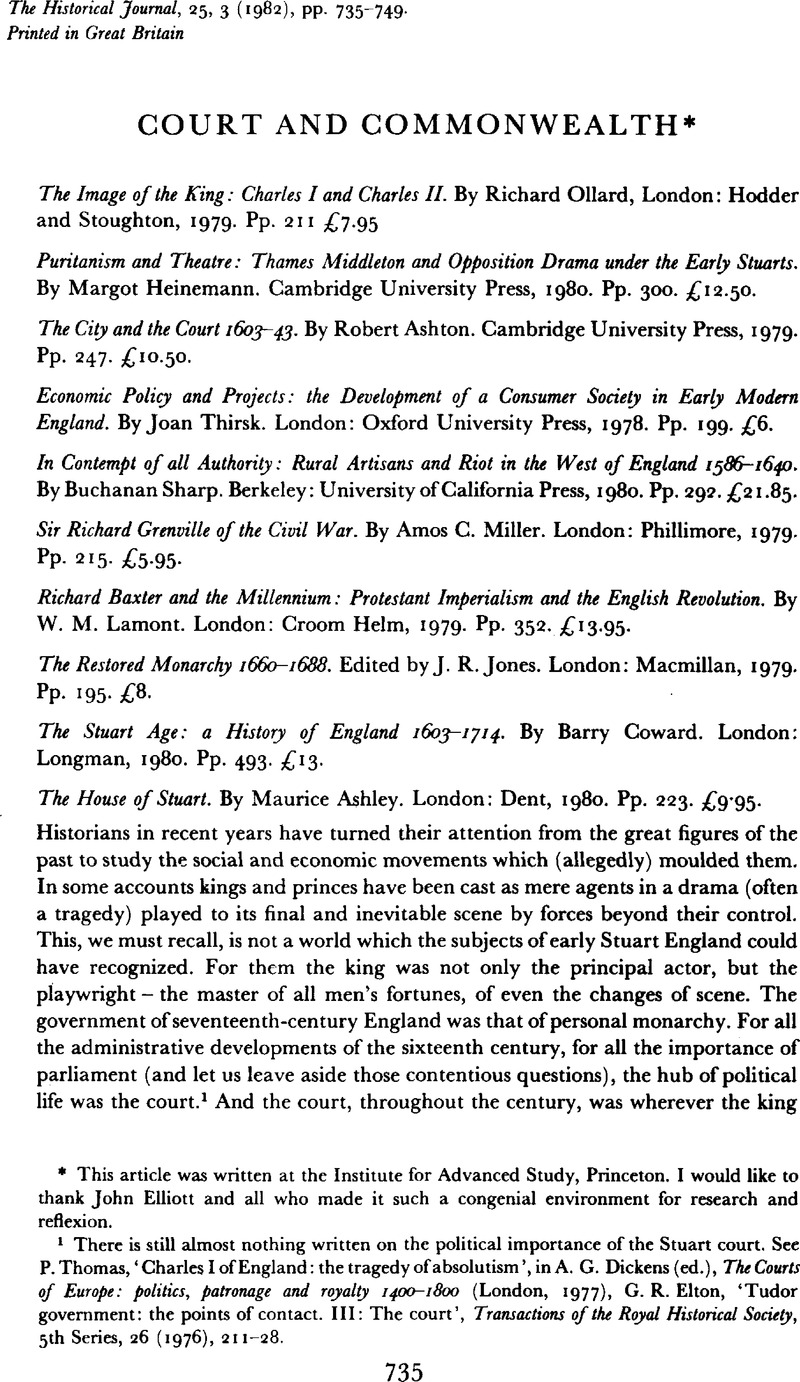

1 There is still almost nothing written on the political importance of the Stuart court. See Thomas, P., ‘Charles I of England: the tragedy of absolutism’, in Dickens, A. G. (ed.), The Courts of Europe: politics, patronage and royalty 1400–1800 (London, 1977)Google Scholar, Elton, G. R., ‘Tudor government: the points of contact. III The court’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th Series, 26 (1976), 211–28.Google Scholar

2 McElwce, W., The wisest fool in Christendom: the reign of James I and VI (London 1958)Google Scholar. For the beginnings of a more favourable evaluation see Munden, R., ‘James I and the “growth of mutual mistrust” ‘, in Sharpe, K. (ed.), Faction and parliament (Oxford, 1978), pp. 43–72.Google Scholar

3 The most recent attempt, Bowie's, JohnCharles I: a biography (London 1975)Google Scholar, was unsatisfactory. For penetrating insights into the character and ideals of Charles see the brilliant essay by Strong, Roy, Van Dyck: Charles I on horse back (London, 1970).Google Scholar

4 Richard Ollard, The image of the king.

5 See my ‘Archbishop Laud and the university of Oxford’, in Jones, Hugh Lloyd, Pearl, Valerie and Worden, Blair (eds.) History and imagination (London, 1981), pp. 146–64.Google Scholar

6 E.g. in July 1625 Chateauneuf reported that the king was devoted to his wife, ‘mais ne lui donne ni lui laisse prendre aucune part dans les affaires’. He later described her as ‘ timide et craintifre’, P.R.O. (Baschet transcripts) 31/3/66 fos. I21v, 213.

7 Ollard, Image of the king, p. 30.

8 Ibid.. p. 80.

9 Ibid.. p. 33.

10 For what can be learned, see Orgel, Stephen, The illusion of power: political theatre in the English Renaissance (Berkeley, 1975)Google Scholar; Orgel, Stephen and Strong, Roy, Inigo Jones 1573–1652: the theatre of the Stuart court (Berkeley, 2 vols., 1973)Google Scholar; Hariss, John, Orgel, Stephen and Strong, Roy, The King's Acadia: Inigo Jones and the Stuart court (London, 1973)Google Scholar; Strong, Roy (ed.), Splendour at court: Renaissance spectacle and illusion (London, 1973); idem, Charles I on horseback.Google Scholar

11 M. Heinemann, Puritanism and theatre.

12 Ibid.. p. 132. My italics.

13 Ibid.. p. 3.

14 Ibid.. p. 106.

15 On the divided nature of the court in 1623 see Ruigh, Robert E., The parliament 0f 1624; politics and foreign policy (Cambridge, Mass., 1971).Google Scholar

16 Fine examples of the kind of investigation that is needed are Ann Barton, ‘Harking back to Elizabeth: Ben Johnson and Caroline nostalgia’, English literary history (forthcoming) and Randall, Dale B., Jonson's gypsies unmasked: background and theme of the gypsies metamorphos d (London, 1974).Google Scholar

17 Robert Ashton, The City and the court 1603–43.

18 Pearl, Valerie, London and the outbreak of the puritan revolution: City government and national politics 1625–43 (London, 1961).Google Scholar

19 Ashton, City and the court, p. 3.

20 This obsession lay behind the commission for buildings, the repair of St Paul's, plans for improved sewerage, regulations governing the use of private carriages (and the incorporation of Hackney coachmen), checks on lodgers in the City, concern for ordering the suburbs and proposals to confine the gold and silver trade to Lombard St. ‘ for the greater ornament and lustre of the City’ (P.R.O. Privy Council Register PC 2/45/404). I shall be developing this theme in a book on the personal rule of Charles I.

21 Ashton, City and the court, p. 129.

22 Ibid.. p. 177.

23 Morrill, J. S., The revolt of the provinces: conservatives and radicals in the English Civil War 1630–50 (London, 1976).Google Scholar

24 Joan Thirsk, Economic policy and projects.

25 Ibid.. p. 75.

26 Ibid.. p. 8.

27 Buchanan Sharp, In contempt of all authority.

28 On the Book of Orders, see Slack, P., ‘Books of Orders: The making of English social policy, 1577 1631’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th Series, 30 (1980), 1–22CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Quintrell, B. W., ‘ The making of Charles 1's Book of Orders ‘ English Historical Review, xcv(1980), 553–72.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

29 Buchanan Sharp, In contempt of all authority, p. 250. See for example Underdown, D. E., ‘Community and class: theories of local politics in the English Revolution’, in Malament, B. C. (ed.), After the Reformation (Princeton, 1980), pp. 147–66Google Scholar; and the remarks of Holmes, Clive, ‘The county community in Stuart historiography’, Journal of British Studies, xix (1980) 54–73.Google Scholar

31 Manchester to Montagu, 28 Oct. 1630; Historical Manuscripts Commisssion, Buccleuch- Whitehall, 1, 270.

32 Buchanan Sharp, In contempt of all authority.

33 Amos C. Miller, Sir Richard Grenville.

34 J S. Morrill, Revolt of the provinces, section 2.

35 W. L. Lamont, Richard Baxter and the Millennium.

36 Ibid.. p. 24.

37 Reliquiae Baxterianae: or Mr. Richard Baxter's narrative of the most memorable passages of his life and times, faithfully publish’d from his own original manuscript by Matthew Sylvester (London 1696). Lamont demonstrates authoritatively that, far from faithful to his subject, Sylvester suppressed Baxter's interests in the millennium.Google Scholar

38 Lamont, Baxter, p. 92.

39 J. R. Jones (ed.), The restored monarchy 1660–1688.

40 John Miller, ‘ The later Stuart monarchy’ in Jones (ed.), The restored monarchy, pp. 30–47; quotation on pp. 32–3.

41 . Jennifer Carter, ‘Law, courts and constitution’, Ibid.. pp. 71—93.

42 The absence of local studies perforce artificially focuses the history of Restoration England narrowly on Westminster politics. A fuller understanding of the later seventeenth century awaits the county histories and perspectives from the provinces which have so valuably illuminated the early Stuart period.

43 J. R.Jones, ‘Parties and parliament’ in Jones (ed.), The restored monarchy pp. 48–70; quotation on p. 57.

44 Howard Tomlinson, ‘Financial and administrative developments in England 1660–80’, Ibid.. pp. 94–117.

45 Dickson, P. G. M., The financial revolution in England: a study in the development of public credit 1688–1756 (London, 1967)Google Scholar. See also Chandaman, C. D., The English public revenue 1660–1688 (Oxford, 1975).Google Scholar

46 Michael Hunter, ‘ The debate over science’, Jones (ed.), The restored monarchy, pp. 176–95.

47 Barry Coward, The Stuart age.

48 Solt, L. F., Saints in arms: purilanism and democracy in Cromwell's army (Stanford, 1959)Google Scholar. Coward follows Kishlansky, Mark, The rise of the New Model Army (Cambridge, 1980).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

49 Coward, The Stuart age, p. 162.

50 Ibid.. p. 46.

51 Ashley, Maurice, The Stuart age (London, 1980).Google Scholar

52 Ibid.. pp. 148–9.

53 Ibid.. p. 202.

54 Hugh Trevor-Roper, ‘History: professional and lay’, delivered at Oxford on 12 November 1957, printed in History and imagination, pp. 1–14.