1. Introduction

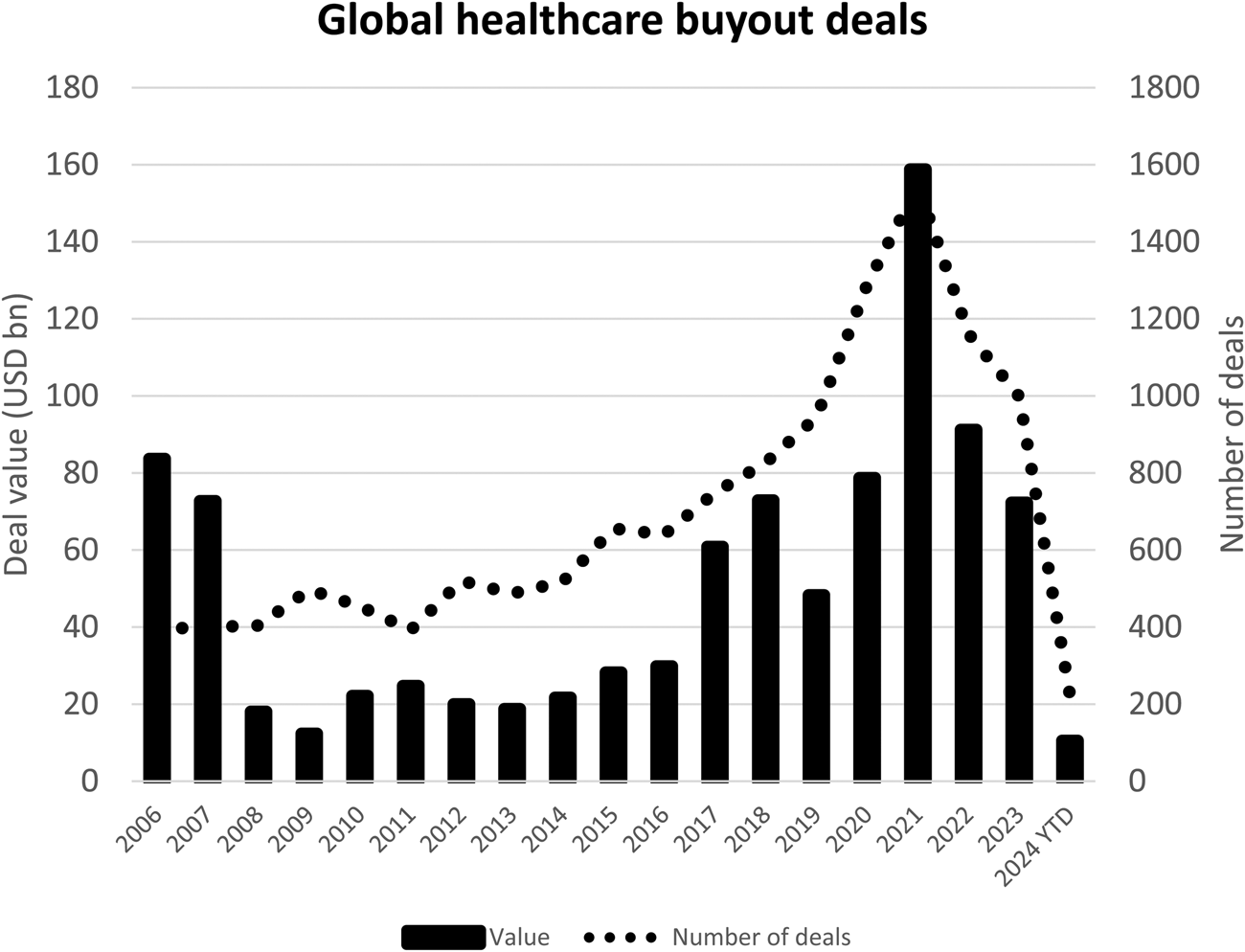

Private equity (PE) firms use capital from institutional investors like pension funds and wealthy individuals, often combined to a large amount of leverage (debt), to purchase companies, restructure and rationalise them, and sell them back within 3–5 years for significant returns (Appelbaum and Batt, Reference Appelbaum and Batt2020). PE firms play an increasingly important role in healthcare. Figure 1 shows the number of buyout deals by PE firms in the healthcare sector globally and their annual value. It can be seen that over the last two decades, PE involvement has increased, although there are fluctuations due to macroeconomic and geopolitical factors (Bain and Company, 2024). Global trends may also differ from movements in specific sectors (e.g. pharmaceuticals, providers, etc.) or geographical areas (e.g. North America is the leading region for PE activity).

Figure 1. Global healthcare buyout deals by PE firms, 2006–2024.

Notes: Sectors covered are medical, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals; chart includes buyouts and secondary buyouts but excludes exit deals.

Source: White and Case (2024).

Existing research on PE in healthcare is growing but remains limited. Indeed, existing studies largely focus on the United States and while nursing homes have been examined in some detail, other specialties have received less attention (Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023). Based on this limited geographic and sector coverage, a recent systematic review concluded that ‘no consistently beneficial impacts of PE ownership were identified’ (Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023) – indeed, the majority of the findings reviewed indicated negative impacts. For example, PE seems to be associated with higher costs to patients or payers and mixed to harmful impacts on quality (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Song, Polsky, Bruch and Zhu2022; Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023).

To stimulate further research on PE in healthcare, the following three key issues appear to be solid points of departure:

(1) PE's significance: What is the relative importance of PE in specific healthcare sectors compared to other types of ownership? What has been the rate of growth of PE involvement over time? What are the main PE actors involved?

(2) PE's strategies: What business models does PE use? Which actors and factors support or oppose PE involvement?

(3) PE's impacts: How does PE involvement affect healthcare operations (quality, costs, health outcomes, etc.), working conditions and the structure of key healthcare sectors?

Clarifying those issues should provide policy-makers with a better understanding of PE involvement in healthcare, as well as a basis to adequately regulate it to attenuate its harmful effects when they exist.

To illustrate, this paper focuses on European primary care, which has received scant attention (Rechel et al., Reference Rechel, Tille, Groenewegen, Timans, Fattore, Rohrer-Herold, Rajan and Lopes2023). It surveys Irish primary care as an example. The Irish healthcare system is mostly tax-funded and services are delivered by the public provider, the Health Service Executive (HSE). However, there has been creeping privatisation and marketisation in key parts of the system over the last several decades, including in the hospital sector (Mercille, Reference Mercille2018b), long-term care (Mercille, Reference Mercille2018a, Reference Mercille, Aulenbacher, Lutz, Palenga-Möllenbeck and Schwiter2024a, Reference Mercille2024b; Mercille and O'Neill, Reference Mercille and O'Neill2021, Reference Mercille and O'Neill2022; Mercille et al., Reference Mercille, Edwards and O'Neill2022; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Mercille and Edwards2023; Mercille and Lolich, Reference Mercille and Lolich2024) and primary care (Mercille, Reference Mercille2019). This has opened the door to global investors, for example, through acquisitions of private providers. In primary care, Ireland is unique among European countries in that it offers no universal coverage; indeed, about half the population must pay out-of-pocket to see a GP (general practitioner – family doctor), while others can benefit from free visits based on income or age (Department of Health, 2023; O'Regan, Reference O'Regan2024). Most GPs are self-employed private practitioners while other primary care professionals (e.g., public health nurses, community language therapists) are salaried public sector (HSE) employees (Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, Brick, O'Neill and O'Callaghan2022). What follows focuses on three key components of the primary care system: primary care centres (PCCs), GP practices and telemedicine.

2. Primary care centres

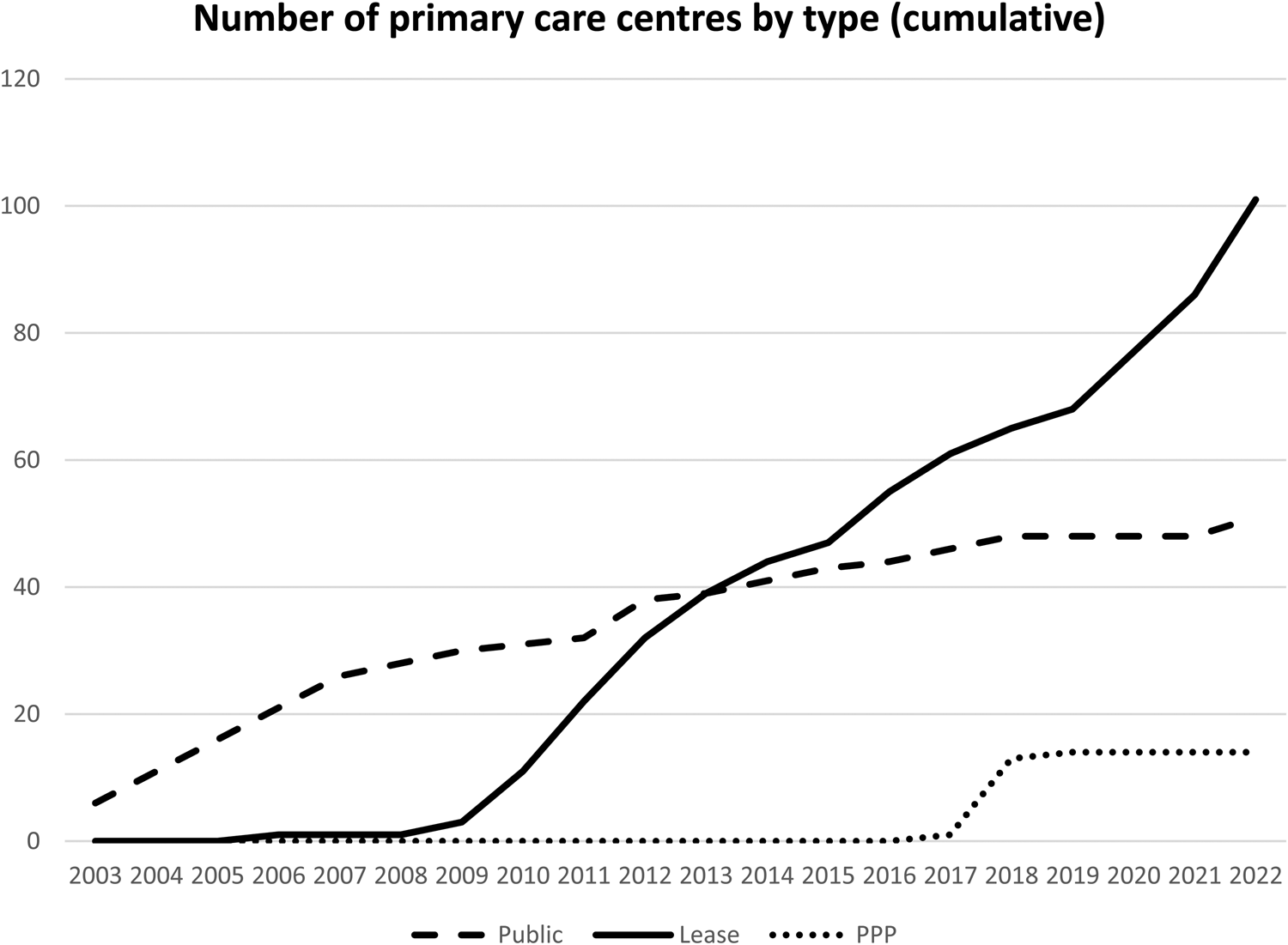

PCCs are buildings in which primary care teams operate, including GPs and other health professionals. A total of 166 PCCs have been established over the last two decades (Figure 2). There are two main types of PCCs: public PCCs are owned, operated and managed by the HSE; operational lease PCCs are owned by a private landlord from whom both the HSE and private companies rent space, typically through a 25-year lease. (A third category is a small number of PCCs developed through public–private partnership.)

Figure 2. Growth of PCCs by type (cumulative).

Note: ‘Public’ = public PCCs; ‘Lease’ = operational lease PCCs; ‘PPP’ = public–private partnership PCCs.

Source: HSE Estates (2023b).

Crucially, in recent years, the government has developed the PCC network largely through operational lease arrangements, of which there are 102 today (Mercille, Reference Mercille2019; HSE Estates, 2023a). This is convenient for the government because it does not require large capital expenditures because it only rents the premises from private landlords. Therefore, a large network of private PCCs is available for institutional investors to acquire, including PE. Currently, KKR (PE firm) and PHP (real estate investment trust – REIT) are the two dominant landlords, each owning about 20 PCCs, some of which have yet to become operational. (REITs pool investors who earn dividends from investments in real estate.) They bought their first PCCs in 2016 (PHP) and 2017 (Valley Healthcare, now owned by KKR). The remaining PCCs belong to small landlords usually owning one PCC, which may eventually be acquired by large investors.

There are several reasons why investors have entered the PCC market (PHP, 2023; Savills, 2023). First, the income stream (rent) associated with the real estate is backed by a state entity and tied to 25-year leases, making PCCs a safe investment. Second, rents are inflation-linked, protecting the value of the cashflows. Third, PCCs are a stated objective of the Irish government, supporting investments in and demand for those services. Fourth, more broadly, those investments correspond to the recent interest in infrastructure assets among asset managers (Plimmer and Wiggins, Reference Plimmer and Wiggins2021; Davies, Reference Davies2022). Infrastructure assets are perceived as less risky and thus offer more stable, progressive returns to investors. The view from investors is that challenges like decarbonisation and digitalisation of the economy will necessarily involve large government investments in infrastructure, creating significant demand for private sector involvement (Davies, Reference Davies2022).

Business strategies consist in buying the real estate but not the operational health companies or services – which is reminiscent of the OpCo/PropCo (operating company/property company) model used by REITs. Health operations are left entirely to the tenants in the PCCs (HSE, pharmacies, GPs, private medical consultants). The owners of the real estate play a role in managing the buildings, but their involvement largely stops there. Collecting the rent is their key source of revenue. Investors buy already existing PCCs or develop new ones. For example, in 2023, PHP acquired the Irish property development and management business Axis Technical Services and signed a long-term agreement with it to develop future primary care projects (PHP, 2023). On its part, in 2021, KKR bought infrastructure investor and asset manager John Laing. The following year, John Laing acquired Valley Healthcare, which owned a portfolio of 20 PCCs. KKR thus acquired sole control of the PCCs through John Laing (Competition and Consumer Protection Commission, 2023).

Because PE involvement in PCCs is restricted to owning real estate and collecting the rent, its influence over healthcare operations and patients is relatively limited. For example, if KKR or PHP decided to sell all their PCCs to other investors, this would not affect the healthcare operations taking place in PCCs because the rents are set through 25-year covenants that would not change. Rent would simply be collected by a different landlord.

Nevertheless, potential risks can be outlined. First, a split between real estate and healthcare operations may be detrimental to the latter as buildings may not be built or designed as adequately as they could be for operational needs. Indeed, some private PCCs were not purpose built and the government has less input on building design and specifications (in contrast, the government has a relatively large degree of control over the design of public PCCs) (Mrowka, Reference Mrowka2014). Second, PE involvement tends to drive consolidation because large investors seek substantial purchases that match their large financial resources. If the trend continues, a large number of PCCs could be owned by a small number of landlords. This could create a power imbalance vis-à-vis the government, which could become increasingly dependent on one or two large financial actors to house its healthcare activities. Therefore, when rents and other matters are negotiated, the government could have less leverage to obtain favourable terms. Put another way, consolidation can lead to anti-competitive behaviour (Batt et al., Reference Batt, Appelbaum and Katz2022).

3. GP practices

There are about 2500 GPs in Ireland (Health Service Executive, 2024). Most are private practitioners and the majority provide services on behalf of the HSE. There has been relatively little consolidation of GP practices. Nevertheless, one company, Centric, has been leading the consolidation of a number of practices over the last two decades (there are very few other consolidators and they are insignificant compared to Centric). Centric was founded in 2004 and today its portfolio has 76 GP practices employing nearly 300 GPs (not all of whom are full time) (Locumotion, 2024). Centric has consolidated, at most, 10 per cent of the sector.

Some of the reasons why PE has penetrated primary care are related to the needs and wishes of existing GP practices. Namely, capital can be scarce and PE is sometimes a source of needed funds, especially within a context of public funding constraints (Ikram et al., Reference Ikram, Aung and Song2021). Also, GPs operating as partners may wish to sell their practices to a consolidator and become salaried to reduce the administrative burden that practice ownership involves (BMJ, 2022).

Accordingly, in 2018, the PE arm of the bank Rothschild & Co made a majority investment in Centric (Rothschild and Co, 2019). Centric's owners recognised that Rothschild could bring capital and expertise to support further growth and geographic expansion (Mercille, Reference Mercille2023). Indeed, since the 2008 financial crisis, traditional banks have been more cautious in their lending, incentivising companies to seek alternative sources of capital like PE investors. Rothschild subsequently obtained a long-term funding line of €50 million for Centric from a consortium of lenders (Haugh, Reference Haugh2020). Moreover, Rothschild has expertise about new markets, which has helped Centric expand in Germany and the Netherlands.

In contrast to the case of PCCs above, Rothschild's PE arm bought an actual healthcare company and as owner, it has more control over its operations than if it only owned real estate to collect the rent. (Interestingly, when Centric buys a practice, it sometimes relocates its GPs to a PCC. Therefore, it is possible for a PCC to be owned by a REIT structure while its GP operations are linked to a PE firm.) PE strategies to maximise revenue and reduce costs (Appelbaum and Batt, Reference Appelbaum and Batt2020; Christophers, Reference Christophers2023) can lead to negative effects that should be investigated further. These could include lower quality of care (Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023) and higher costs due to overtreatment, upcoding or overreliance on services like diagnostics (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Song, Polsky, Bruch and Zhu2022), in addition to disruptions to continuity of care. Those potential risks should be assessed against PE firms' claims that the additional capital and expertise they bring can result in cost savings and better care provision, for example, through investment in innovative technologies.

4. Telemedicine

Accessing GP services through telemedicine has become significantly more popular during the Covid-19 pandemic. Since 2020, there have been over 400,000 video-enabled consultations with patients in Ireland (Health Service Executive, 2023). In 2023, 21 per cent of adults consulted a GP through telemedicine, compared to 2 per cent in 2020 (Irish Medical Council, 2023). PE and venture capital have entered the sector decisively. A key strategy has been to offer telemedicine services through private insurance companies. In Ireland, about 47 per cent of the population has private health insurance (The Health Insurance Authority, 2023), largely provided by three insurers. All offer plans including online GP consultations provided through private companies backed or controlled by PE/venture capital: (1) Irish Life provides the services through Centric, which is owned by Rothschild's PE arm (see above); (2) VHI provides the services through HealthHero, which has significant financial support from PE firm Marcol; (3) Laya Healthcare offers online GP consultations through WebDoctor, which is backed by PE firm VentureWave.

The growth of telemedicine has been driven by a number of factors. To begin with, it can offer benefits to patients and doctors, creating a demand for the service, which was especially the case during the Covid-19 pandemic. For example, telemedicine can improve access for patients in remote locations (as in rural areas) and certain groups of patients are satisfied with it (CPME, 2021). Its growth potential has generated interest from PE. The case of HealthHero illustrates how PE may enter the sector. HealthHero's website claims it has become a leading telemedicine provider in Europe, with operations in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Germany and France while having provided 4 million consultations by 4200 clinicians with 30 million patients (HealthHero, 2024). Its growth was made possible by PE investments in the company (Billing, Reference Billing2020). Those investments financed the acquisition of rival digital health companies in Europe and enabled HealthHero to grow its offerings and expand geographically.

There are several potential risks with online GP consultations through corporate telemedicine providers (CPME, 2021). For example, the United Kingdom's Care Quality Commission (CQC) found that 43 per cent of the online primary care providers it surveyed were not providing safe care according to regulations (Care Quality Commission, 2018). Issues included inappropriate prescribing of opioid-based medicines and antibiotics, while patient data may also be exposed in digital platforms. Perhaps most important, continuity of care (seeing the same GP), which is fundamental to ensuring quality of care, can be disrupted by online consultations that assign patients to available doctors, who may not always contact the patient's regular GP, as noted by primary care organisations in Ireland (Walley, Reference Walley2018). Those important issues should be investigated further in the case of telemedicine in Ireland.

5. Conclusion

This paper has outlined a research agenda to better understand PE in healthcare by focusing on its significance, the reasons for its recent involvement, its strategies and potential impacts on health operations and outcomes. In turn, this research should guide policy-makers, regulators and academics in exploring the regulation of PE in health. This applies to several areas. First, systematic data collection is needed to better understand PE in healthcare and its impacts on health outcomes. This is a challenging task given the opacity of PE funds' operations and structures, but regulations calling for more transparency would help. Second, regulations on PE financial arrangements should be explored, including limits on ownership concentration, market share and leverage. Third, regulations on health operations to prevent adverse impacts are important, including health staffing requirements, billing and health professionals' control over clinical operations. Fourth, regulations establishing minimum quality standards and patient satisfaction should be explored. Fifth, regulations to protect and improve working conditions for healthcare workers would help attenuate potential negative impacts of PE ownership (e.g., cost cutting). Sixth, from a broader perspective, attention should be paid to the factors that give rise to PE involvement in healthcare. Addressing those causes would reduce reliance on PE. For example, if the administrative burden faced by GPs was reduced, they would be less inclined to sell their practice to corporate owners; and if public funding was increased, healthcare providers would be less likely to seek capital from PE firms.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

None.