Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 August 2011

1 According to Pseudo-Clementine Horn, i.8 seq., Christianity was first preached in the streets of Alexandria by Barnabas. This tradition is of very doubtful historical value.

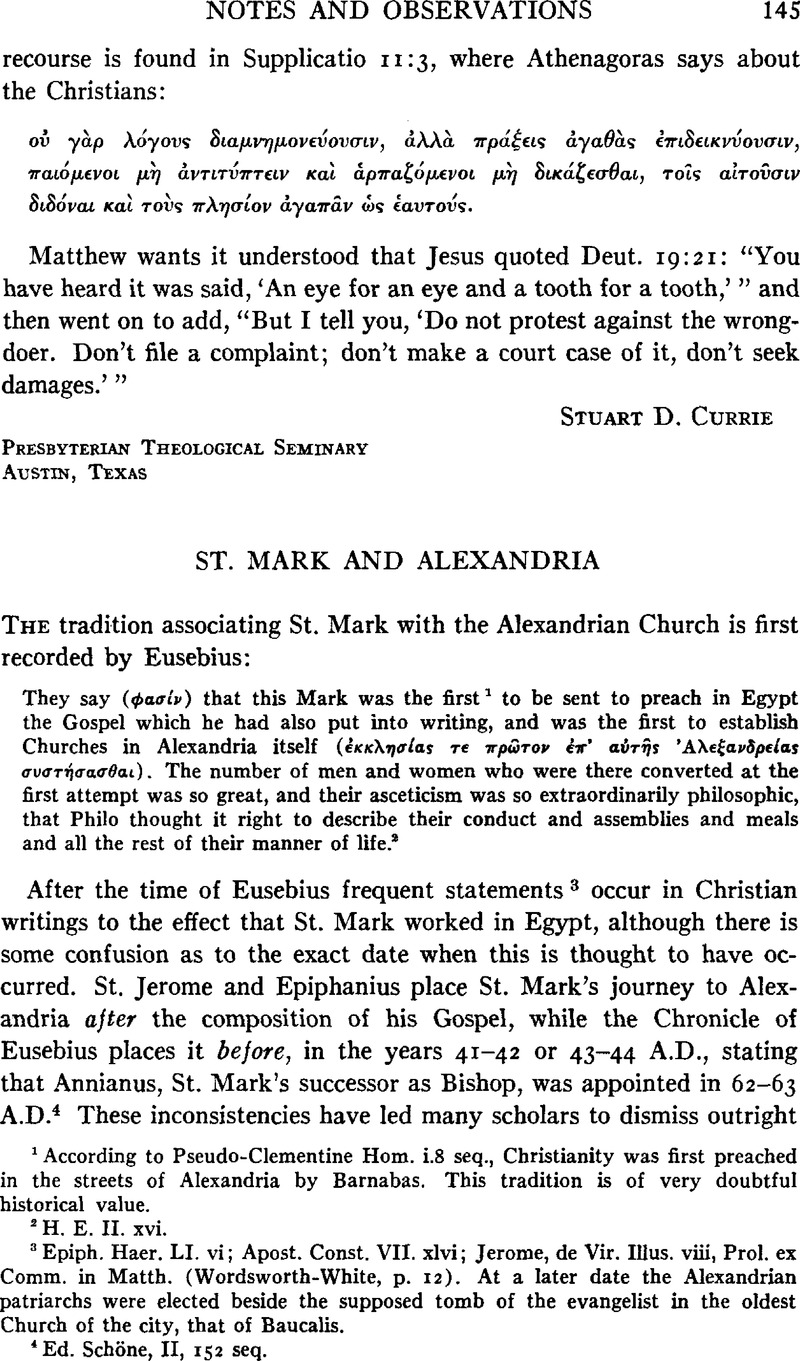

2 H. E. II. xvi.

3 Epiph. Haer. LI. vi; Apost. Const. VII. xlvi; Jerome, de Vir. Illus. viii, Prol. ex Comm. in Matth. (Wordsworth-White, p. 12). At a later date the Alexandrian patriarchs were elected beside the supposed tomb of the evangelist in the oldest Church of the city, that of Baucalis.

4 Ed. Schöne, II, 152 seq.

5 The tradition is also absent from the earliest Latin Gospel prologues — see Dom de Bruyne, Revue Bénédictine 40 (1928), 196 seq. Cf. also the lack of knowledge of Dionysius, Bishop of Alexandria in the third century, in Eus. H.E. VII. xxv. On the Alexandrian succession of Bishops see A. Harnack, Chronologie, I, 124 and 202 seq.

6 Papias ap. Eus. H.E. III. xxxix; Iren. III.i.1., x.6; Tert. adv. Marc. IV.v; Clem. Alex. ap. Eus. H.E. VI. xiv; Origen ap. Eus. H.E. VI. xxv.

7 Archbishop Carrington, The Early Christian Church, I, 202, however, suggests that the reference to “Mark my son” in 1 Pet. 5: 13 implies the recognition of a successor in the Rabbinic tradition of teaching which would give Mark enhanced authority in the Church.

8 JTS 50 (1949), 155–168.

9 P. Katz, JTS 46 (1945), 63–5, thinks that the change to codices was a result of the early Church's differentiating itself sharply from Judaism, which was essentially a religion of the sacred roll.

10 Note the words of C. C. McCown, HTR 34 (1941), 234: “From whatever directions Christianity came to Egypt, it must have come chiefly from a place where the codex was already well established in Christian usage, or it could not have made its way against Egyptian immemorial custom. It is natural, but not necessary, to assume that Italy is the source.” McCown believes that the early Christians used codices from the first (p. 235). One of the first scholars to uphold this view was the eminent German philologist Wilhelm Schubart, Das Buch bei den Griechen und Römern (2nd ed., 1921), pp. 119–23.

11 Dr. Morton Smith of Columbia University is shortly to publish an unknown piece which he thinks is by Clement of Alexandria, dealing with the secret parts of the Gospel of Mark. If this identification is proved correct, it would strengthen the connection between this Gospel and Alexandria. (I owe this information to the kindness of Prof. K. Stendahl.)

12 If there was ever any break, it is likely to have occurred at the time of the Jewish revolt against Trajan, when Alexandria was devastated. Yet even if this occurred (and we have no knowledge that it did), Christianity was soon a force again.

13 CAH, XI.

14 Athan. Apol. Contra Arian. ii. 35.

15 L. E. Elliott-Binns, The Beginnings of Western Christendom (1948), p. 126.

16 The Emperor Domitian had the public libraries of Rome, which had been devastated by fires in previous reigns, liberally restocked with fresh manuscripts from Alexandria (Suet. Dom. xx).

17 The excellence of this service was also due to Egypt's being the corn granary of Rome, which had a small corn harvest in proportion to its vast population. The Emperors knew that a scarcity of corn in Rome would bring in its train discontent among the populace, and so the maintenance of a steady supply from Egypt was an imperial concern for which a special department of the administration was responsible. The Emperors managed Egypt as a parent company today will manage its smaller associates overseas. Indeed, so close was the imperial supervision that Roman nobles were not allowed to set foot in Egypt without permission.