Introduction

A swathe of recent studies has highlighted the complexity of attitudes toward, and the historical experience of, disability in antiquity. Deploying lenses from contemporary disability theory, numerous important works have critiqued portraits of sensory and physical impairments in early Jewish and Christian literature and problematized healing narratives.Footnote 1 Others demonstrate how postmortem ideals communicate attitudes to bodily infirmities and perfection.Footnote 2 Elsewhere, archaeologists have debunked earlier assumptions, such as that those with lifelong impairments would simply not have been raised from infancy or would have been incapable of economic participation in adulthood.Footnote 3 Increasingly, the picture emerging from this research is of mixed attitudes to impairment across antiquity’s diverse literature, geography, and communities.

This article illuminates further elements of this complexity with a case study: a healing story with a twist in expectations. My focus is a narrative encounter in which a character named Antipatros asks the apostle John to heal his twin sons, in a Greek fragment identified as the second-century Acts of John 56–57.Footnote 4 This passage, I suggest, turns on the criticism of a character with negative attitudes to his impaired sons. However, demonstrating the continued importance of intersectional factors, the text nonetheless remains focused on what this means for the flawed male, elite character of the father, with whom the audience is likely to identify, rather than the experience of the sons.

In the following discussion, after outlining the episode, I suggest that the narrative makes a two-layered critique that subverts expectations about the situation of the healed characters. First, it censures medical commerce, in a form familiar from other texts. Second, it exploits a series of ambiguities and negative characterizations found also in other literature to critique Antipatros himself and the request for his sons’ healing that he makes of John. I argue that the passage’s focus rests on this critique and, as the narrative undermines Antipatros for his attitude toward, and proposed strategies to address, his sons’ impairments, it indicates a nuanced approach to disability. While the sons are in some senses doubly endangered, John’s help is required to save the sons’ lives not primarily from their illness but from their father. And yet, other narrative features retain a mixed message. While the character of the apostle John ultimately comes to focus on the sons, the narrative itself silences the sons from any speaking part. This mixed message brings to life the complexity of portraits of disability in antiquity: even passages that embed critique of negative responses to impairment can remain focused on the characters thereby criticized rather than giving voice to the experience of characters with impairments. Such dynamics warrant close attention as we continue to fill out the picture of attitudes to disability in antiquity.

Antipatros, His Sons, and John

The fragment begins by narrating the apostle’s departure from Ephesus and arrival at Smyrna, at which point a large crowd gathers. Having heard that John is a miracle worker, Antipatros, a member of the Smyrna elite, approaches John with a proposition. He offers ten thousandFootnote 5 pieces of gold and then describes the condition of his sons:

I have twin sons who since birth have been possessed of a demon and who have suffered terribly: they are thirty-four years old. In one moment both may fall faint, sometimes in the baths, sometimes while walking, often while eating, and sometimes even at a public gathering in town. You will see for yourself that they are well-built men, but they are overcome by this malady that possesses them every day. (56.6–14)Footnote 6

Having set out the typical manifestations of his sons’ condition, Antipatros exhorts John for their healing; it is a request for assistance in his advanced age. There is a short interaction between John and Antipatros, in the presence of the sons. John dismisses the offer of money and requests instead that Antipatros give his soul in exchange. Ignoring John’s comments, Antipatros renews his request, noting the indiscriminate approach John has taken in healing all until now as a precedent for the request that John not neglect his sons. Having already alluded to his readiness to “take a deadly decision” (56.14–15),Footnote 7 Antipatros finally discloses that he has plans to take his sons’ lives: “With the agreement of my kinsfolk I was prepared to kill them with poison on account of the derision,Footnote 8 but you who have come as a faithful doctor invested by God, for their sake, enlighten them and help them” (56.24–27).Footnote 9 Once this plan is revealed, John moves immediately into a prayer and then a successful exorcism and healing, which leads to a baptism and dismissal as the episode closes.

In the manner of ancient fiction (commonly noted as important background for the Apocryphal Acts, though the genre is subverted in many ways), it seems that everything ends on a happy note.Footnote 10 John has acquiesced to Antipatros’s request, healed an illness that was a source of much derision, and righted an economic hardship for an aging man who would struggle to support well-built male adult children once he also became too frail to work. But I suggest there is more going on in this text: Antipatros is himself the focus of an important critique as the narrative unfolds.

A Critique of Medical Commerce

The first layer of critique in the text lies in Antipatros’s expectations of John as an entrepreneurial medical practitioner charging extortionate fees.Footnote 11 The description of the sons’ infirmity (56.6–14), as cited above, is set out in the terms in which the “falling sickness” was known; in some sources this condition is described (given its attribution to spiritual causes) as “the sacred disease.”Footnote 12 Earlier scholarship suggested this condition was epilepsy.Footnote 13 Though recent scholarship rightly demonstrates concerns about attributing modern diagnoses to ancient texts,Footnote 14 it is also worth noting that there was an ancient terminology for epilepsy (ἐπιληπτικός; cf., e.g., Plut. Lyc. 16.2). In a Greek treatise dated to the fifth century BCE and included in the Hippocratic corpus, The Sacred Disease, the anonymous author discusses the illness’s etiology while countering opposing practitioners who he says erroneously identify spiritual causes of the illness (Morb. sacr. 1.1–16). The treatise goes on to discuss the illness’s effect on patients of different ages, delineating various presentations (and thus prognoses) and suggesting that those who had experienced the symptoms since birth and beyond puberty, as in the case of Antipatros’s sons, were unlikely to improve (Morb. sacr. 11–15).Footnote 15 Indeed, Antipatros describes an escalation of his sons’ symptoms, claiming that their childhood experience of the disease was difficult but that they suffer terribly now as adults because “their demons have grown up too” (Acts of John 56.16–17). This likewise mimics the language of The Sacred Disease, where the author discusses the generally irreversible trajectory of the illness when it has “grown and been nourished with the body” since infancy (Morb. sacr. 14.1–2).

Antipatros’s description of his sons’ condition reveals an effect on life and social consequences that we might describe in the language of disability. Contemporary disability theories offer a variety of ways of conceiving of the relationship between an impairment or infirmity (a description of a person’s physiology, morphology, and so on), and “disability” (a context-dependent social construction).Footnote 16 But the key distinction to note is that disability indicates an additional attribution about a feature of a person that attracts stigma or special attention and is considered “disabling” in a given context. Although disability is often taken to be a contemporary construct, there are signs of an awareness of a similar category in ancient sources, as Rebecca Raphael convincingly argues of the frequent colocation of the “blind,” “deaf,” and “lame.”Footnote 17 Varied ancient texts confirm that stigma about the sacred disease was commonplace. The Sacred Disease 15.1–14 observes that adults hide away when they feel an episode coming on, being more experienced at reading the signs than children.Footnote 18 From this perspective, it is interesting that seizures in public gatherings are listed in Antipatros’s climatic final example of his sons’ symptoms (Acts of John 56.11–12). The whole description makes the reader aware that the sons suffer a terrible disease that brings daily shame upon the family.Footnote 19 It is clearly disabling in Antipatros’s account. And it is lifelong.

Ancient treatments for the falling sickness are varied, reflecting differing explanations of etiology. Anna Rebecca Solevåg delineates two broad frameworks through which the illness’s causes were understood in the ancient world: invasion (a spirit takes internal command of the sufferer) and imbalance (symptoms arise through a systemic imbalance within the sufferer).Footnote 20 Treatments might include changes to diet and lifestyle, or pharmacological therapies.Footnote 21 In keeping with the view that illness beginning in childhood and extending to adulthood makes recovery unlikely, as described above (cf. Morb. sacr. 11–14), ancient sources demonstrate general pessimism about the efficacy of treatment.

Such skepticism likewise reflects common ethical criticisms of certain medical practices. For the author of The Sacred Disease, other physicians’ misunderstandings of the causes of the illness are shown in a range of inappropriate remedies they prescribe, through which they may avoid any responsibility for the outcome. He claims: “These observances they impose because of the divine origin of the disease, claiming superior knowledge and alleging other causes, so that, should the patient recover, the reputation for cleverness may be theirs; but should the patient die, they may have a sure fund of excuses, with the defence that they are not at all to blame, but the gods” (Morb. sacr. 2.29–33).Footnote 22

Moreover, the considerable expense associated with any treatment was considered open to exploitation (a common strand of criticism that no doubt also reflects the interests and biases of those who wished to criticize other “freelance” medical practitioners).Footnote 23 In his treatise That the Best Physician Is Also a Philosopher, Galen criticizes “practitioners who are no physicians, but poisoners … lovers of money who abuse the Art for ends that are opposed to its nature.”Footnote 24 Guilia Ecca notes that “the charge of greed (φιλαργνρία), which reduces the goal of the medical practice to the physician’s μισθός, is typically attributed to physicians from the classical era onwards.”Footnote 25 And she discusses ancient writers who attempt to distinguish the proper practice of medicine from the behavior of those deserving of such a charge.

Antipatros’s opening gambit with the huge financial offer is a targeted criticism of those whose medical assistance would require this kind of capital, while also possibly flagging Antipatros’s desperation.Footnote 26 This dynamic is familiar from references in the canonical gospels, such as in the description of the woman with the flow of blood who has been made destitute by the charges of unscrupulous doctors (Mark 5:26). Just as Jesus heals the woman without payment, John’s first words to Antipatros in response are: “My healer” (he emphasizes that he is not the healer himself) “works without payment, and heals freely” (Acts of John 56.18). This is a common theme among ancient sources. In the pseudonymous “Hippocratic” Letter 11, Hippocrates likewise refuses payment and argues for the free practice of medicine.Footnote 27

But in the Acts of John, as the passage continues, John’s speech shows that there is an expectation of some kind of trade: “in exchange for illness he accepts the souls cured. What are you prepared to give, Antipatros, in exchange for your sons? Give your soul to God and you will find your sons in good health by the power of Christ” (56.19–22).

The narrative certainly critiques expensive and possibly exploitative medical practices. The amount of gold discussed is hyperbolic; the kind of exaggeration we might expect of texts in this genre.Footnote 28 The reader is able to see that this is a preposterous price. John’s proposed exchange is, however, also complex.Footnote 29 Are the sons—or, more precisely, removal of the additional burden that Antipatros claims they place on him as he ages—simply a bargaining chip in winning Antipatros to Christ?

Through their concept of “narrative prosthesis,” David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder have offered an important framework for making sense of some uses of characters with disabilities.Footnote 30 They observe that narratives frequently rely on characters with disabilities, so that it is not that such characters are absent from literary sources (as we might find with some other marginalized identities in antique and modern sources), but rather they are both “pervasive” and employed in a “hypersymbolic” way. Mitchell and Snyder’s concept explains superficial use of characters who are not given full personalities, agencies, or backstories, but whose presence in the narrative is simply to support another narrative purpose, which in turn relies on a negative representation of disability in the broader social context. Here, the archetypal example might be a villain who is portrayed with a physical or sensory impairment—Peter Pan’s Captain Hook with his missing limb, or the frequent trope of facial disfigurements in villains in James Bond films. Negative attitudes toward the disability or disfigurement support the negative characterization.Footnote 31 As discussed further below, by keeping the sons silent, the Acts of John’s treatment of Antipatros’s sons retains a mixed message. Nonetheless, as the narrative focuses on Antipatros, the sons’ disability forms an integral part of the text’s critique of him. Unlike the features Mitchell and Snyder identify in narrative prosthesis, where a passage relies on negative representations of disability, however, here the text critiques the negative response to the sons’ disability, with Antipatros himself coming under further layers of marked criticism.

Antipatros: Concerned Father or Villain?

The narrative does more than reframe Antipatros’s understanding of appropriate medical assistance. I suggest it undermines Antipatros and his whole approach to his sons’ impairments. In what follows I argue that the narrative communicates this critique through his threat to take his sons’ lives, his financial position, and his name, as well as by the structure of the dialogue and its ambiguous ending.

A. Attitudes to Infanticide and Filicide

Antipatros’s plot to take his sons’ lives is central to his negative characterization. Rather than making him a sympathetic character, it constructs him with traits that various ancient texts, including early Christian sources, attribute to negative or more primitive “others,” in contrast to the groups with which the writer identifies. This warrants a brief survey of the ways in which such texts present fathers taking the lives of their children.

1. A father’s right to take the life of an adult son: There is a frequent assumption among discussions of Roman family structures that the patria potestas included within it a particular “right over life and death” (ius vitae ac necis), whereby the paterfamilias had a legislated right to determine whether the offspring over whom he held legal fatherhood would live or die.Footnote 32 In fact, this concept is dubious. In a thorough study of the legal and economic details of the patria potestas, Antti Arjava notes that the so-called right over life and death “seems always to have been mainly symbolic, and in Late Antiquity it was clearly considered obsolete,”Footnote 33 while Brent D. Shaw and Richard P. Saller each seek to offer a detailed survey of any relevant evidence of the “right” and conclude that it never existed.Footnote 34

There are some texts in which taking a son’s life is presented positively. These are not legal texts, but exempla, recorded by writers like Sallust and Livy in their first-century BCE Latin histories, or Valerius Maximus in his first-century CE Latin collection of exempla. Here, the presenting issue is one of disciplining delinquent or felonious sons; the exempla play on a tension between a father’s duty to the empire, frequently arising from a formal office such as senator or consul, and his paternal instincts. In a famous example, Brutus arrests, flogs, and beheads his sons because they tried to reinstate Tarquin against Brutus’s efforts. In the words of Valerius Maximus: “he put off the father to play the Consul, and preferred to live childless rather than fail to support public retribution” (5.8.1; cf. Livy 2.2–5). Similarly, writing about the Catiline conspiracy, Sallust describes “Fulvius, a senator’s son, who was brought back from his journey and put to death by order of his father” (Sall. Cat. 39.5; cf. V.M. 5.8.5). But, as Shaw asserts, the actions of such a father are praised not for exercising a right as a paterfamilias, but because he follows through with the obligations of his office despite a presumed paternal affection that might have predisposed him to mercy.Footnote 35 In other examples from rhetorical schools, in which historical cases mix with fictionalization, characters in dialogues assert a father’s right to take his son’s life. Seneca the Elder’s first-century CE Latin Controversies describes a certain Gallio, who “felt that the difference between a grandfather and a father was that the former could reprimand or discipline a grandson in order to protect him, whereas the father could kill his son” (Sen. Controv. 9.5.7). However, as the ensuing discussion addresses this topos for a debate, it results not in the affirmation of a legal right over life and death but in refuting Gallio’s claim.

Thus, not only are the examples of fathers taking adult sons’ lives embedded in texts about the dilemmas arising from a clash of political office and paternal feeling,Footnote 36 but even where a general right is considered (and refuted), the texts that explore the murder of adult children do not relate such a choice to infirmity. It seems that second-century readers of the Antipatros episode are unlikely to see here a reference to a father’s right to take the life of adult children.

2. Infanticide in Greek and Roman texts: A right over life and death is often also cited as legal backing for practices of infanticide and exposure. The 1980s and 1990s saw a particular interest in publications on these practices in antiquity, with discussion of both legal and literary sources leading to a variety of claims about the prevalence of, and attitudes toward, fathers (or midwives, mothers, or enslavers) causing the death of unwanted infants.Footnote 37 This important scholarship also suggested evidence of selective infanticide/exposure practices, identifying groups at particular risk: female infants, children conceived through infidelity, pregnancies reaching term after divorce or the death of the father, the children of slaves, and—most relevant to the story of Antipatros’s children—infants believed to display evidence of an infirmity or disfigurement.Footnote 38 In the latter case, references to infanticide have frequently been interpreted as reflecting a general attitude that children with disabilities were deemed “not worth rearing.”Footnote 39

Despite the importance of this work, recent studies are more cautious in their conclusions, recognizing the scant sources before the fourth through sixth centuries CE that address legal and historical questions directly and the importance of contextualizing references in literary sources.Footnote 40 That there is evidence for the practice of exposing unwanted newborns is not disputed.Footnote 41 For instance, in an oft-cited letter found at Oxyrhynchus, a man exhorts his wife to expose a newborn if female: “I beg and entreat you, take care of the little one, and as soon as we receive our pay I will send it up to you. If by chance you bear a child, if it is a boy, let it be, if it is a girl, cast it out” (P. Oxy. 4.744.6–10).Footnote 42 How to determine the practice’s prevalence or emphases is more contested. In the case of this documentary evidence from Oxyrhynchus, though often cited as indicative of a general attitude, it is worth noting that this is a single example.Footnote 43 The content does parallel a joke in third-century BCE New Comedy,Footnote 44 which might indicate a wider awareness of historical selective exposure of females and/or disdain for the idea of such a practice.

Indeed, as far as they can be gleaned, the attitudes promoted in sources, particularly those that seem to present normative views, are most helpful in considering a reader’s expected response to Antipatros’s stated intention of killing his impaired sons. Similarly, it is important to separate material on practices of “abandonment,” which Ville Vuolanto argues were intended to spare the child as a foundling, from actions explicitly intended to take the child’s life.Footnote 45 With this in mind, the following briefly considers attitudes to infanticide in legal material, philosophical accounts of the state, and ethnographic treatments of other groups.

Legal support for infanticide in Greek and Roman antiquity is partial at best. Cicero includes a statement that attributes infanticide of offspring with deformities to the Twelve Tables. Cicero’s reference is not presented as a citation of the Twelve Tables specifically but is an illustrative aside that he attributes to Quintus’s comments on the powers of tribunes. Quintus claims that, though revived shortly afterwards, the tribune’s power had for a period been “quickly killed, as the Twelve Tables direct that terribly deformed infants shall be killed” (cito necatus tamquam ex duodecim tabulis insignis ad deformitatem puer).Footnote 46 This is the extent of the extant material about infanticide attributed to the Twelve Tables by authors from antiquity.Footnote 47 Notably, it does not link the infanticide to a specific “right over life and death” based on patria potestas.Footnote 48 Other sources explore legal questions arising from fathers wishing to take back children abandoned and then reared by others; though potentially complex in their own way, these do not relate to the legality or otherwise of taking the child’s life.Footnote 49

The sentiment Cicero attributes to the Twelve Tables bears a particular resemblance to idealized accounts of the state in Plato and Aristotle and then, later, in Dionysius of Halicarnassus’s summary of Romulus’s state. In the account of the idealized state in his Republic, Plato prioritizes children of elite parentage and stipulates that infants who are “born defective (ἀνάπηρον)” should be concealed in a remote place (ἐν ἀπορρήτῳ τε καὶ ἀδήλῳ) (460c). Plato provides eugenic reasons for these measures. Aristotle becomes more explicit, advocating for a law that “no deformed child (πεπηρωμένον) shall be reared” (Pol. 1335b). Here, Aristotle imagines a range of laws that he would like to see enforced, including exercise for pregnant women and prohibiting procreative sex when couples are either younger or older than an ideal age, to improve the quality of offspring. It is clear in the broader context of both Plato’s and Aristotle’s accounts that the texts are theorizing about the conditions of an ideal human community, but they are not describing any real legal framework. This still passes judgment upon children with deformities (as also on inactive pregnant women), though it is interesting that few later works take up their ideas.

One key, though much later, writer, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, offers mixed information about the treatment of unwanted children in his first-century BCE Greek historiography, Roman Antiquities. At 9.22.2, he claims that Romans since ancient times were obligated to raise all their children, without exception. But elsewhere he asserts that Romans of Romulus’s time were required to rear all sons and at least first-born daughters, with the further caveat that they may not “destroy any children under three years of age unless they were maimed or monstrous (ἀνάπηρον ἢ τέρας) from their very birth” (Ant. rom. 2.15.2).Footnote 50 In the event that children in these exceptional cases were to be killed (through exposure), Dionysius indicates that the five closest neighbors needed to consent. Dionysius’s historiography famously presents an interest in antiquated practices of the Roman past (as is common in literature of the imperial period). He focuses on reframing a romanticized past to which the present time is in some ways beholden but from which it has also developed. Dionysius is not, notably, suggesting that such infanticide continues to his present day but is providing a primeval legal framework that he attributes to the legendary Romulus (himself a foundling). Here, the archaic “past” is a kind of “other.”

A range of other sources on infanticide, including infanticide of children with infirmities, likewise situates the practice within a description of another group, from which the author and implied audience are importantly distinct. In particular, some ethnographic sources include infanticide as part of communicating a stereotype of others. For instance, looking back from his own first-century CE Roman position, Quintus Curtius describes Alexander’s progress through India. He attributes to “the barbarians” the belief that their group “excels in wisdom” and goes on to observe:

The children that are born they acknowledge and rear, not according to the discretion of their parents, but of those to whom the charge of the physical examination of children has been committed. If these have noted any who are conspicuous for defects or are crippled in some part of their limbs, they give orders to put them to death. (Quint. Curt. Alex. 9.1.24–25)Footnote 51

Immediately following, other customs are mentioned. The differences between the priorities of marriage in Roman society and those of this Indian group as constructed by the text (such as marrying for beauty alone) are expounded, furthering the exotic but ultimately negative portrait of the society’s priorities and traditions.Footnote 52 Similarly, Caesar’s Gallic War criticizes the Gauls for their treatment of wives and children, including infanticide and, for instance, earlier funerary fires that burned the deceased’s “slaves and dependents” (Bell. gall. 6.19). This construction of the Gallic past serves to underscore Rome’s superiority for the reader.Footnote 53

In the same way, from his early second-century vantage point, Plutarch offers a detailed description of the Spartans in his Life of Lycurgus. Significantly, the archaizing treatment of the Spartans interacts with implications of more primitive habits in early Rome. So he can say:

The elders of the tribes officially examined the infant, and if it was well-built and sturdy, they ordered the father to rear it, and assigned it one of the nine thousand lots of land; but if it was ill-born and deformed (ἀγεννὲς καὶ ἄμορφον), they sent it to the so-called Apothetae, a chasm-like place at the foot of Mount Täygetus, in the conviction that the life of that which nature had not well equipped at the very beginning for health and strength, was of no advantage either to itself or the state. (Plut. Lyc. 16.1–2)

Plutarch also offers an account of diagnostic activities the women would engage in, bathing infants in wine, which would distinguish “epileptic and sickly infants” from “the healthy ones” (16.2).Footnote 54 The passage continues with Spartan customs in raising children, and the claim that Spartan nurses were sought after by Roman parents (16.3).

A key element in these descriptions lies in the affirmation that the Rome of the writer’s time has moved beyond these earlier traditions, whether of Romulus’s Rome or the Rome that admires the Spartans’ customs. It is a romantic construction of a possible past, rather than texts to give historical weight. In Plutarch’s account of the Spartans, infanticide contributes to polemic against the foreign other.Footnote 55 And in portraits of Rome like that of Dionysius’s, even when infanticide is mentioned, it is to set out some limitations on the situations in which it was permissible.Footnote 56

Recent archaeological studies indicate that children with various infirmities were raised, including those with conditions like cleft palate that would have been evident from birth.Footnote 57 Hippocratic sources describe treatments for limb abnormalities from birth.Footnote 58 Indeed, disability theory helps to illuminate the unhelpful (and unhistorical) binaries that lie behind an assumption that children with visible impairments or disfigurements were considered not worth raising; many infants, children, and adults in antiquity navigated life with some kind of impairment, whether congenital or acquired through accident or poor nutrition.Footnote 59 Neither Cicero’s implied requirement of infanticide of “deformed” newborns nor the prescriptions in Plato’s or Aristotle’s idealized states appear to have been enforced.

In addition to these references to infanticide, proponents of some philosophies are more outspoken in their criticism. Stoics express particularly strong disapproval (see especially first-century Roman Stoic Musonius Rufus, frag.15),Footnote 60 as do Jewish and Christian groups. Casting such practices as the negative habits of others is also a key feature of the references in early Christian texts and, I suggest, illuminates the polemic against Antipatros in the Acts of John episode.

3. Infanticide and othering in early Christian texts: Early Christian texts foster strong polemic about the immorality of infanticide, building on earlier Jewish and other opposition to such practices (cf. Wis 12:5; Philo Spec. 3.110–116; Jos. C. Ap. 2.202).Footnote 61 The Christian texts explicitly set themselves against other groups that they claim practice infanticide. In unpacking the features it claims make Christians superior to those of other local traditions, the second-centuryFootnote 62 Greek Epistle to Diognetus explains that Christians “marry like everyone else and have children, but they do not expose them once they are born” (5.6). Similarly, the Didache and the Epistle of Barnabas include the instruction “do not abort a fetus or kill a child that is already born” among a list of commandments for those on the path of light (Barn. 19.5; cf. Did. 2.2), which contrasts by implication with the practices of those on the alternate path.Footnote 63 In a detailed tour of the afterlife, the Ethiopic Apocalypse of Peter—dated to the first half of the second century and providing the earliest surviving Christian tour of hellFootnote 64—lists groups of people who had committed particular sins, including a section that details explicitly the punishment of parents who committed infanticide (Eth. Apoc. Pet. 8.8).Footnote 65

In this way, like other Greek and Roman texts that include infanticide among the traits of a foreign or otherwise different other, the Christian texts construct an opposing group using graphic language. The Christian rhetoric in these texts gives less attention to historical questions about the behavior of rival groups than it does to rendering another group as monstrous. These criticisms help to illuminate a second-century reader’s reaction to Antipatros’s plan.

4. Implications for the narrative about Antipatros and his sons: The texts surveyed in the previous sections suggest a number of implications for audience responses to Antipatros’s plan to take his sons’ lives. It seems unlikely that a second-century reader would simply accept a father’s right to kill his adult son. They may be aware of people practicing infanticide, though also of others who raise children with infirmities. But, for literary texts, by this time infanticide is associated with foreign communities rather than with (superior) contemporary Romans. Early Christian texts take this polemical use even further.

The examples closest to the scenario in the Acts of John might be those that describe the infanticide of newborns with various infirmities (including, in Plutarch’s account of the Spartans, epilepsy), and where a larger group is required to give permission. An understanding of such descriptions may lie behind Antipatros’s claim to have consulted his family (56.24–25).Footnote 66 However, given the extremely negative characterization of infanticide wherever it is mentioned in other early Christian texts, it is most likely that the Antipatros account presumes an audience that would not view the destruction of offspring sympathetically.Footnote 67 Moreover, Antipatros’s claim is about killing adult children, relevant examples of which relate to a clash of civic duties and paternal affection for erring sons. These are not about the murder of those with infirmities and related economic considerations.

Thus, when the reader discovers that Antipatros was planning to kill his sons,Footnote 68 it seems the realization would not create sympathy, aligning the situation with an accepted, if tragic, practice made necessary by difficult circumstances. Rather, it would feed into these caricatures of the monstrous other, who could countenance murdering even their own children. In these ways, Antipatros’s masculinity is also drawn into the criticism. In the Roman world, masculinity is presented on a sliding scale; individuals may be identified with various forms or strata of unmanliness as they are shown to fall short of the ideal masculine type. Deeply tied to virtue, self-mastery is a central attribute for the performance of masculinity, and a feature that is likewise considered basic to the capacity to rule over others.Footnote 69 Thus, by aligning Antipatros with behavior so emphatically unvirtuous in early Christian literature, the text undermines the masculinity Antipatros might claim as a leading man of Smyrna (56.3), and removes the basis of his masculine right to rule over others. In these ways, the passage does not support Antipatros’s plan, or his performance of his role as father or disciple. Further features of the text confirm this negative portrayal.

B. Economics and Mercy

Antipatros’s economic interests are also a source of critique. When Antipatros seeks John’s assistance for himself, in his old age, he suggests his sons’ infirmities threaten his economic means. Such economic matters do feature in texts about parents and children with disabilities in antiquity. Later Christian material, while still denouncing the exposure of infants, shows an increased tendency to attend to the economic reasons that led parents to consider this option, as evident in the fourth-century Greek writings of Basil of Caesarea. In Basil’s Letters 217 to Amphilochius, he states:

Let the woman who neglected her new-born child on the road, if, though able to save it, she condemned it, either thinking thereby to conceal her sin or scheming in a manner altogether beastly and inhuman, be judged as for murder. But if she could not care for it, and it died both on account of the wilderness and the lack of necessities, the mother is to be pardoned. (217.52 [Deferrari, LCL])Footnote 70

In Stephen Friesen’s poverty scale, those with disabilities, given exclusion from employment, share a place in the lowest socioeconomic category, “below subsistence level,” with unattached widows, beggars, prisoners, and so on, making up, by his estimate, 28 percent of the urban population in the Roman Empire.Footnote 71 More recently, however, Emma-Jayne Graham has provided evidence of manual work fulfilled by people with physical impairments, challenging assumptions that people with disabilities did not participate economically.Footnote 72 Nonetheless, for Antipatros, old age is a reason to request mercy, first for himself, and only then for his sons (Acts of John 56.17), claiming, at least, the financial drain of his sons’ condition.

Further aspects of Antipatros’s portrait raise doubts about his financial excuse. The amount of gold he claims to have available to pay John might be hyperbolic (and possibly intended to indicate desperation), as noted above, but he was introduced as one of the elite (πρῶτος) of Smyrna. The audience is invited to wonder whether they should trust Antipatros and his claim of impending hardship.

Indeed, economic issues are a key concern in the Acts of John, in which generosity to the poor and voluntary poverty are hallmarks of true discipleship.Footnote 73 Preaching in Ephesus, John claims that he is “no merchant who buys or exchanges goods,” but through him Christ will lead the crowd away from their error of having been “sold into ignominious lusts” (33.5–9). He warns: “do not lay up for yourselves treasures upon earth,” and, particularly relevant, “Do not think, if you have children, to rest on them, and do not seek to rob and defraud on their account!” (34.4–7). Rather, the poor should not mourn, or the rich rejoice in their treasures, which can offer no consolation (36.1–4, 10–13). Indeed (suggesting a dependence upon Luke 16.19–31): “If you kept your treasures without helping the poor, having left this body and being in the flames of the fire, you will find no one who will have mercy on you when you are begging for mercy” (35.5–8).

In the final sentence of the pericope involving Antipatros, after the healing, John likewise exhorts Antipatros to voluntary poverty and generosity to the poor: “John besought Antipatros to give his money to those in need” (57.9–10). It is a hefty ask in light of the large sum initially mooted in the negotiation over the healing. Antipatros makes no response. He has been undermined from his opening speech by caring not about his sons directly but about a healing that would reverse their inability to provide for him and release him from the cost of supporting them. Despite other indications of Antipatros’s elite status, moreover, his failures here go to a weakness in his performance of masculinity as paterfamilias and perhaps even reveal a hope (as disparaged in the Acts of John 34.5–7) to rest on the contribution of his children. Indeed, his concern about economic hardship, when he occupies such a position of advantage, suggests a desire to maintain an economic position that is criticized in interactions about discipleship across the Acts of John.

C. Calling a Spade a Spade

The narrative portrays Antipatros critically not only through his murderous plans and unsympathetic economic interests but through a persistent identity label; arguably, the most obvious thing about Antipatros is his name. In a study of the twenty-six character names used across the Acts of John, Boris Paschke identifies sixteen that he claims are “speaking names.”Footnote 74 He draws on studies of ancient comedies to illustrate this literary tradition of naming characters in ways that either confirm, or ironically counter (through antiphrasis), some key feature of their character, behavior, or context. The fifth- to fourth-century BCE playwright, Aristophanes, is a prominent user of this tradition. Similarly, Plautus, a playwright of Latin comedies in the third and second centuries BCE, portrays a character, who is a “moneylender and profiteer” and obsessed by money, called Misargyrides, a name based on the Greek μισαργνρία, “hatred or contempt of money.”Footnote 75

This same tradition is at play in the Acts of John. Callimachus (Καλλίμαχος), meaning beautiful or noble fighter, aggressively pursues Drusiana, even to the point of making arrangements to rape her corpse (Acts of John 62–71). He is certainly a fighter but is far from noble, as the narrative underscores, describing him as “a servant of Satan” (63.2).Footnote 76 Similarly, Fortunatus is the ironic embodiment of one touched by Fortuna, with her good fortune and capricious changes of fortune.Footnote 77 He first encounters wealth but, unluckily, dies from a snakebite; then, by apparently good fortune, he is raised, but he is later reported to have died from the venom still circulating in his body (70–86).

Antipatros’s name includes much of the same irony and humor.Footnote 78 The way he is introduced, as “a certain man by name Antipatros,” may also serve to draw attention to the significance of his name.Footnote 79 The prefix ἀντι– supplies numerous meanings in the Greek, including that “one person or thing is ‘instead of’ another,” or—perhaps surprisingly—“equivalent to” another.Footnote 80 In this way, the prefix can come to mean either a thing or its opposite. This is an ambivalence that, Paschke argues, the author exploits. But while the name creates ambiguity, I suggest the behavior ensures that—like Callimachus or Fortunatus—what emerges is irony. Antipatros is presented as the father, and named as ὁ πατήρ explicitly in 57.7, but through his actions he is cast as the opposite.Footnote 81

Indeed, Antipatros himself is the greatest threat his sons face. What he presents as an attempt to secure the sons’ welfare has, since the beginning of the passage, been framed as an effort to protect his own position. He initially exhorted John to “assist me in my old age” (56.14), and he closes by saying, “Take pity on me and on them” (56.17)—in that order. When he comes to focus, finally, on the needs of the sons (“for their sake, enlighten them and help them”; 56.26–27), his request is for John to intervene to save the sons from his own plan to take their lives. He is indeed the opposite of a good father.

Thus, as Callimachus is a fighter, but without the nobility implied by his name, and Fortunatus, although initially lucky, is ultimately a victim of a capricious change of fortune, Antipatros is both “like or equal to” a father and its opposite. He is the father of the sons but acts as their adversary.

D. A Disconnected Dialogue

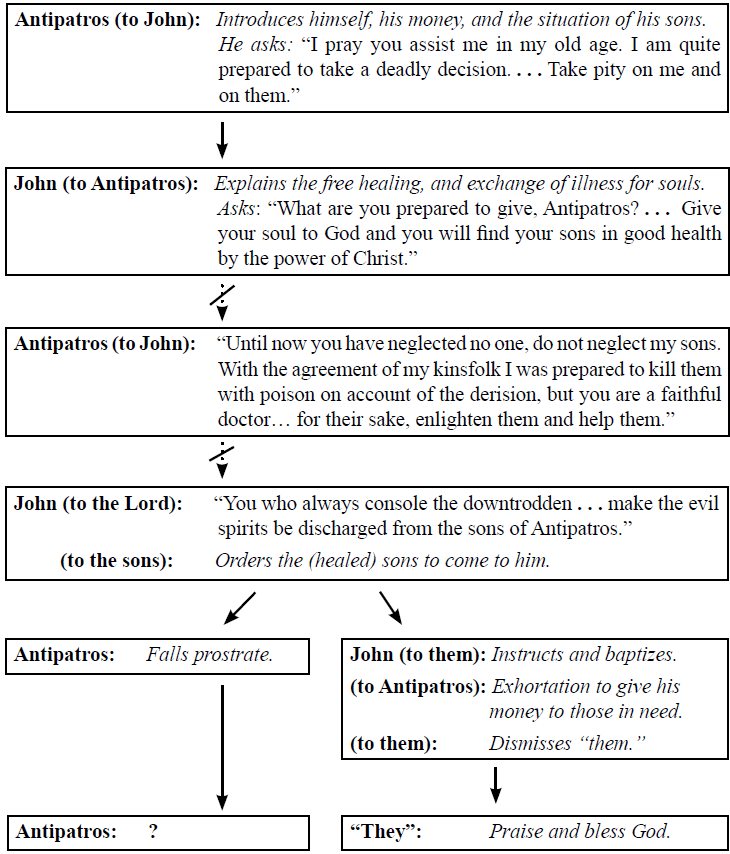

Disjointed moments in the dialogue between Antipatros and John, with the sons and the crowd all standing by silently, also contribute to the way the text undermines Antipatros. The following diagram shows the moments of disconnection, as Antipatros and John speak or act past each other.

After Antipatros’s initial speech and John’s response, Antipatros simply ignores John’s question, “What are you prepared to give?” (56.20). Rather than complying with the terms of John’s transaction, he objects that John has not neglected anyone else and he simply reiterates his request (focused on his own position in this potential healing). This time he clarifies his threat on the sons’ lives (56.24–25).

John is immediately moved to action. In an important shift of dynamic, rather than addressing Antipatros further, he turns to address the Lord in prayer. Antipatros’s final words were “for their sake, enlighten them and help them” (56.26–27), and the narration goes to the effort of an extra term to show the parallel in John’s response, describing his action as a result of “having been called upon” (57.1). John then prays: “You who always console the downtrodden and who called me to aid, you who have never waited to be called to console because you are present before we seek your assistance, make the evil spirits be discharged from the sons of Antipatros” (57.1–5).

It is not clear whether assistance was previously necessary, though it is notable that John did not initially reject Antipatros’s claims about the need for healing. Rather, he refuted the particular kind of financial (rather than spiritual) exchange Antipatros proposed. But the dialogue clarifies that this healing help now is required urgently to save the sons’ lives, not from the illness, but from their father. The illness could cause social exclusion and other distressing experiences, including the potential risk to life through the possibility of a seizure while bathing (56.10), but the condition does not generally pose an imminent risk of death. By contrast, the father is an immediate and genuine danger.

After the successful exorcism, John calls not Antipatros but the sons to him. The interaction is not so much a “dialogue” as Antipatros failing to acknowledge John, and John turning instead to prayer and then to address the sons.

E. The Ambiguous Ending

Having undermined Antipatros’s character in these various ways, uncertainty remains at the end of the narrative. The narrative does not describe a visual element to the exorcism or explain how it is known that the frequently invisible ailment is gone; there is thus apparently need to clarify: “the father saw them in good health” (57.6–7). While John focuses on the sons (their “falling sickness” cured), now it is Antipatros who falls over at the sight of their recovery. But Antipatros falls and lies prostrate (ἔπεσεν καὶ προσεκύνησεν) before John (57.7). The προσκννέω terminology suggests worship, and perhaps this is a response of conversion and piety. Or perhaps it is another case of Antipatros’s missing the mark, worshiping John instead of understanding John’s point that he himself is not the healer.Footnote 82

The reader is then told that John baptizes “them”Footnote 83 and exhorts Antipatros “to give his money to those in need” (57.10). Finally, John dismisses “them” and “they” praise and bless God. Throughout the narrative, a firm distinction has been made between Antipatros and his sons. It is a distinction Antipatros himself underscores, such as in his call for mercy upon “me and them”—there is no “us.” Each reference to αὐτοί in the pericope until now refers to the sons only, and that is the main way to which they are (namelessly) referred. Perhaps part of the healing here has been to draw the family together under the one pronoun, praising and blessing God. Or perhaps all of these αὐτοί references still simply refer to the sons. They have been called to John. They have responded. They have been baptized—with a trinitarian formula that may yet suggest some tension between the πατήρ of the formula and the Antipatros of their reality. They have been dismissed and leave with faithful responses; the plural pronoun means it must be at least the sons who have this response.

But the question is: Is Antipatros among them? All the reader may be sure of is that initially Antipatros did not seem open to the exchange of his soul for his sons’ health, though he is astonished at or grateful for the healing, and that he (like other would-be disciples) has been exhorted to give away his money. Will he respond to the final request to give away his gold pieces, and will he be a better disciple than he has been a father? Or is this yet another disconnect in Antipatros’s engagement with John? The episode ends without resolving these questions.

Conclusion

The story of Antipatros and his sons offers a case study that fills out the picture of attitudes to disability in early Christian literature. The treatment is, unsurprisingly, not simple. Within the comedic and dramatic elements of the narrative, clear criticism of Antipatros and his proposed strategy to address the problems arising (in his own life) from his sons’ impairments shines through. By way of Antipatros’s initial offer of a huge payment for healing, the passage ties its criticism into a wider denigration of extortionate medical practices. Antipatros then comes under sustained criticism as both father and inquiring disciple through his threat of murder, economic circumstances, and name. The structure of the narrative supports the negative portrait, while leaving his ultimate choices ambiguous. In the end, the sons are healed, an act that will, according to Antipatros, remove derision and improve his economic prospects. But, significantly, the healing is prompted not by the initial description of the sons’ symptoms but by Antipatros’s declaration of his intent to kill his sons. He is the most urgent threat to their safety, prompting John to act swiftly.

While the passage critiques Antipatros’ failures, however, it still makes the story about him. The text leaves the sons silent and unnamed. There is no attempt to delve into their own account of their experiences—for instance, as their father explains (to a stranger) his intention to take their lives, as he sets out the daily manifestations of their infirmity and its cost (to him), or as the stranger turns to them in prayer, healing, and baptism. There is a final account of their praise following their baptism, but not the particular words of which it might be comprised. Like other episodes in the Acts of John, the flawed and (potentially, eventually) redeemed elite, male characters like Andronicus and Callimachus (Acts of John 62–86), and here Antipatros, are the focus as cautionary characters, while the characters presented wholly positively, like Drusiana (Acts of John 62–86), or Antipatros’s unnamed sons, are idealized, and often silent. Here, the text leverages the sons’ silence in order to “move the narrative forward”Footnote 84 with respect to the plot-points in which it is interested: the errors of Antipatros and a pedagogical threat of the consequences of such failures. And in this regard, it uses the sons and their silence as a crutch.

But, contrary to Mitchell and Snyder’s description of narrative prosthesis, the narrative dynamic here does not rely ultimately on negative attitudes to disability. Quite the reverse: it relies on negative attitudes in the wider context of early Christianity toward infanticide as a response to infirmity and to disciples who cling to economic and social advantage. In the story of Antipatros, we encounter a second-century text’s critique of a character whose attitudes lead him to contemplate destruction of those with infirmities. In response, the apostle turns to invoke divine consolation of those whose presence in the story is, and to a large degree remains, obscured.