The debate over the definition, the operationalization and the measurement of ‘populism’ dates back to times when populism was only sporadically used by political scientists and sociologists (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016). Whatever the approach used to describe populism – a thin-centred ideology (Mudde Reference Mudde2004), a communication style (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016), a synonym for political illiberalism (Pappas Reference Pappas and Thompson2016a), an empty signifier (Laclau Reference Laclau2005), a political mobilization tool (Jansen Reference Jansen2011), a discursive tool (Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007) – the literature has now dealt with multiple aspects of the populist phenomenon. To name just a few topics, populist attitudes among voters (Castanho Silva et al. Reference Silva B2020), the presence of populism in party manifestos and leader discourses (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Kaltwasser2018; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, de Lange and van der Brug2014), populism in party organization (Vittori Reference Vittori2020), the mainstreaming of both left and right populism (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, De Lange and Rooduijn2016; Damiani Reference Damiani2020) and populist parties in opposition (Louwerse and Otjes Reference Louwerse and Otjes2019). One of the most debated issues is the relationship between populism and the so-called ‘qualities’ of (liberal) democracies (Morlino Reference Morlino2011). On the one hand, scholars depict populism as troublesome for liberal democracy (Rummens Reference Rummens, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017): populism is considered as inherently conflictual with crucial aspects of this regime, namely pluralism, a mediated form of political representation and the checks and balances between institutions (Abts and Rummens Reference Abts and Rummens2007; Pappas Reference Pappas2016b; Urbinati Reference Urbinati2013). Other scholars argue that while populism may be a threat, it may also be a corrective for democracy: its presence might foster inclusiveness and highlight legitimate issues neglected by the mainstream, while endangering other aspects of liberal democracies such as public contestation (Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Kaltwasser CR2012, Reference Kaltwasser CR2014; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012a). Finally, other scholars (Laclau Reference Laclau2005, Reference Laclau2006; Mouffe Reference Mouffe2018) hold a much more positive view of populism: in their interpretation, populism is seen as a liberating force for the masses, as it allows instances from below to fill the empty signifier of populism. In this debate, however, with few exceptions (Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf2016a, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b; Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart Reference Kaltwasser CR and Taggart2016; Spittler Reference Spittler, Kneip and Merkel2018), comparatively less has been said about the role of populist parties in government and their impact on the qualities of democracy. As populism is growing electorally and several populist parties have gained access to government (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, De Lange and Rooduijn2016), it is worth investigating their impact on the political regime in which they operate. The research questions that this article aims to answer are: (1) whether populism impacts (negatively or positively) the qualities of (liberal) democracy; (2) whether the impact changes depending on the role that populists have in government; and (3) whether a specific type of populism is more harmful than others. While the literature has already dealt with the first aspect, the second and the third aspect are less investigated by comparison (see below).

This article is structured as follows: the first part briefly outlines the distinction between the types of populism and their electoral trajectories in the past few decades. It goes on to review the literature on the relationship between populism and liberal democracy in order to set up three hypotheses related to the threat-or-corrective thesis. The following empirical section is divided into three parts, one for each hypothesis outlined in the previous section: using longitudinal data from the Global State of Democracy Index (GSoDI), it shows that populist parties in government significantly and negatively affect almost all qualities of democracy under analysis. Yet, the hypothesis that the more relevant the role of the party, the higher the impact is not confirmed in toto. Evidence also shows that, with some nuances, exclusionary populist parties in government impact more negatively than other forms of populism and non-populist governments.

Defining the types of populism in Europe, assessing their electoral strength and their participation in government

Scholars have always struggled to define the nature of populism; Isaiah Berlin (Reference Berlin1968) stated that defining populism is like biting a sour apple due to the difficulty of finding a way to conceal all kinds of manifestations related to populism. In this regard, one of the main features of populism is its ‘chameleonic’ (Taggart Reference Taggart2000) essence. More recently, the literature has identified four core populist features: (1) the central position of the people; (2) the homogeneity of the people; (3) anti-elitism; and (4) a sense of perceived political, economic and cultural crisis related to the exploitation of the people (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2013). Following the thin-centred ideology approach proposed by Cas Mudde (Reference Mudde2004), another important feature of populism is that it is frequently accompanied by a hosting ideology which complements those ideological aspects that populism does not include.

Focusing on the hosting ideology as the main classificatory characteristic, the literature has identified in the exclusionary and inclusionary traits (Font et al. Reference Font, Graziano and Tsakatika2019; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012b) the most relevant distinction between populist types. A less recurrent type in Europe is the so-called neoliberal populism (Pauwels Reference Pauwels2010; Weyland Reference Weyland1999). Exclusionary populists are usually associated with parties belonging to the radical right party family: as a nativist party family (Mudde Reference Mudde2007), populist radical right parties target the outgroups, such as immigrants and ‘other’ minorities who cannot belong to the ‘real’ people. Being excluded from the ‘people’ implies that these ‘outsiders’ cannot have the same political and economic rights as the ‘people’: the ‘in-group’ has strict boundaries, whose surveillance is left to the people of the ‘in-group’. On the other hand, for inclusionary populists, economic, financial and oftentimes political elites represent the outsiders, as they threaten the unity of the people, perpetuating a system of economic exploitation in which the majority of the people is excluded. Admittedly, this type of anti-elitism, albeit framed in a different way, is typical of exclusionary populists as well. However, contrary to exclusionary populists, inclusionary populists want to give a voice to disregarded groups, to highlight the ‘dignity’ of indigenous populations as well as expanding welfare programmes to include the poor (Font et al. Reference Font, Graziano and Tsakatika2019). For that reason, inclusionary populism is more frequently associated with radical left (Damiani Reference Damiani2020) and sometimes social democratic parties.

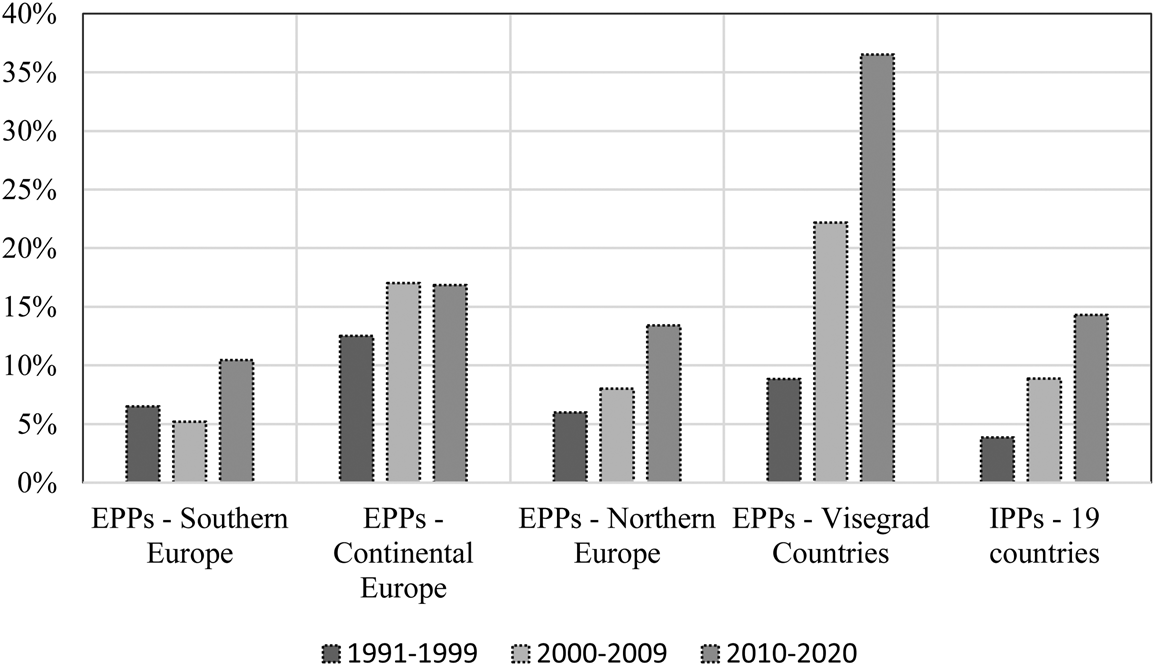

Indeed, populism in Europe has been more frequently associated with radical right parties, not only for their electoral success (van Kessel Reference Van Kessel2015), but also for the relative marginality of other types of populism (Font et al. Reference Font, Graziano and Tsakatika2019). Using the ParlGov data set (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2020) and the PopuList (Roodujin et al. Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel and Froio2019) (see Online Appendix, Table 1A for the full list), Figure 1 sums up the electoral results of exclusionary populist parties (EPPs) divided into geographic areasFootnote 1 and inclusionary populist parties (IPPs) in 19 European countriesFootnote 2 in the last three decades. Figure 1 shows that EPPs are more successful than IPPs. In particular, in Visegrad countries, EPPs are now the most relevant party family, while the area where EPPs underperformed is Southern Europe, where IPPs have recently accessed power (SYRIZA in Greece in 2015 and Podemos in Spain in 2019).

Figure 1. Electoral Results of Exclusionary (EPPs) and Inclusionary (IPPs) Populist Parties in 19 Countries

Source: Electoral results from Döring and Manow (Reference Döring and Manow2020); case selections from Roodujin et al. (Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel and Froio2019).

Note: See Online Appendix, Table 1A for the whole list.

For the purpose of this article, however, it is also necessary to analyse the presence of populist parties in government, whatever their hosting ideology. Table 2A in the Online Appendix provides a full list of all populist parties in government from 1991 to 2019, while Table 1 shows the frequency of the inclusion of populist parties in government over the last three decades. Table 1 reports the percentage of the years spent in government by populist parties from 1991 to 2019 and also shows the roles of the respective populist parties in governments.

Table 1. Participation of Populist Parties in Government as a Percentage of All Years: with respect to Figure 1

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Note: Each country has 29 years in government (551 in total). For each year in government (YG), I compute whether the government in office is either populist or non-populist. In the election years or in the cabinet reshuffle years, I assigned the YG to the government that was in government for the longer part of that year, e.g. if a populist party enters the government in May, succeeding a non-populist government, then the year is counted as if the populists were in government. If a populist party enters the government in October, succeeding a non-populist government, then the year is counted as if non-populists were in government.

Table 1 reveals that populists have been excluded from government (78.9% of the cases in the whole data set) most of the time. However, their presence in European governments became more frequent in the last decade (2010–19): from the first decade (1991–2000) to the last one (2010–19), the share increased by almost 30 percentage points. Populist parties were predominantly junior partners to non-populist parties: in all three decades under consideration this is the government typology which is more frequent. Yet, as of 2018, six countries were ruled by populist major partners (in three cases in coalition with populist junior partners) (see Online Appendix Table 2A).

Populism in government: a threat to liberal democracy?

The literature has thus far produced several ‘normative’ or ‘ideal’ definitions of democracy – that is, definitions of democracy with adjectives, which by their nature cannot be realized in full, but whose actual implementation can be empirically tested (Dahl Reference Dahl1989; Sartori Reference Sartori1987a). For example, Leonardo Morlino (Reference Morlino2011) identifies eight ideal types, among which he includes liberal democracy, while Michael Coppedge et al. (Reference Coppedge2011) find six types. These ideal types expand the minimal (procedural) conceptions of democracy, like the ones identified by Joseph Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1942) or by Robert Dahl (Reference Dahl1971). Following Dahl (Reference Dahl1971), the liberal democratic ideal type is structured by eight institutional guarantees that are aimed at freely selecting candidates in order to realize majority rule through a fair procedure (electoral campaign), while at the same time protecting minority rights in order to avoid the tyranny of the majority.Footnote 3 Thus, liberal democratic systems combine liberty and equality, since ‘all equalities are not democratic acquisitions, just as all freedoms are not liberal conquests’ (Sartori Reference Sartori1987b: 384).

If the liberal democratic ideal type balances the majority rule – the most basic assumption for a democracy without adjectives is that all power goes to all people (Sartori Reference Sartori1987a: 45) – and equal and fair participation, pluralism (in the media and in political representation) and the protection of minorities are its main corollary. Since one of the defining features of populism, as highlighted above, is its people-centrism – that is, treating the polity as a non-conflictual and homogeneous body – one may wonder what the relation is between populism and a political regime that (ideally) recognizes and protects pluralism. The most straightforward answer to this question is that the two concepts are antonyms and indeed Takis Pappas (Reference Pappas and Thompson2016a) has defined populism as political illiberalism, precisely for the conflictual nature between the pluralist dimension of liberalism and the people-centrist monism of populism.

Yet, populism has been perceived as a corrective to how liberal democracy works in real life: as Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012a: 17) put it, ‘the ambivalence of the relationship is directly related to the internal contradiction of liberal democracy, that is, the tension between the democratic promise of majority rule and the reality of constitutional protection of minority rights’. Moreover, the inherent tension between populism and other qualities of the liberal democratic regime is well-known (Canovan Reference Canovan1999; Plattner Reference Plattner2010): as the increasing inclusion of the people within democratic institutions implies that the democratic process becomes less intelligible and transparent (Canovan Reference Canovan, Mény and Surel2002), populism finds a fertile ground for targeting several procedural and substantial aspects of the democratic decision-making architecture, their most fundamental criticism being of representative politics (Taggart Reference Taggart2004). The hostility towards representative politics derives from the populist conception of the ‘people’ as a homogeneous identity that the corrupt elites try to split for their own interests (Mudde Reference Mudde2004). For critics of populism, the idea of a homogeneous polity conflicts with the basic principle of pluralism as well (Abts and Rummens Reference Abts and Rummens2007; Pappas Reference Pappas and Thompson2016a; Rummens and Abts Reference Rummens and Abts2010; Urbinati Reference Urbinati2013). This is not to say that populism is non-democratic per se when it comes to political representation (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012a; Müller Reference Müller2016), since populist parties do participate in the elections and do not mean to overthrow the democratic institutions as such (Mény and Surel Reference Mény and Surel2002).

On the other hand, populism is also seen as a potential ‘corrective’ for democracy, especially when it comes to participation of the excluded groups, political mobilization of neglected issues (Laclau Reference Laclau2005) and the non-mediated involvement of the ‘people’ in decision-making (Vittori Reference Vittori2017): the unfulfilled promises that democratic institutions generate (Canovan Reference Canovan1999) may be delivered by a populist appeal to participation (Laclau Reference Laclau2005), as populism in this interpretation allows the ‘people’ to take back politics from below (Mouffe Reference Mouffe2018). Opponents of such a view claim that this type of populist mobilization hides an ultra-majoritarian view of society, in which minorities (in the case of EPPs) are excluded from the people (Plattner Reference Plattner2010).

To sum up, populism is expected to impact democratic institutions in four respects: the first concerns the concept of political representation of the ‘homogeneous people’, from which it derives a second aspect: either the lack of protection for minority groups in the case of EPPs or, conversely, their inclusion in the polity in the case of IPPs. The third concerns the concept of pluralism, since pluralism conflates with the homogeneity of the people principle (Pappas Reference Pappas and Thompson2016a), and the fourth concerns participation, as populists are believed potentially to mobilize disenfranchised sectors of society (Laclau Reference Laclau2005).

Besides the normative debate, the most comprehensive study on populists in government in Latin America found that ‘populist rule has had largely negative effects on the legal and institutional constraints’ and that ‘populist governments fail to enhance participation’ (Houle and Kenny Reference Houle and Kenny2018: 280–281). A similar conclusion is reached in another comprehensive work (Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b) on nine countries in Latin America: populism in government harms the democratic quality of a country. Yet, populism in opposition is found to have a positive effect. In the European case, recent analyses on the relationship between the quality of democracy and populism show that, contrary to Latin American populism, the presence of populism in government does not lead to a complete breakdown or the erosion of democracy (Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b, Reference Huber, Schimpf, Heinisch, Holtz-Bacha and Mazzoleni2017b). However, it was also found that right-wing populism in government has a much more negative effect on minority rights compared with left-wing populism, while the ‘mutual constraints’ quality, which measures the relevant counter-powers in a given political system, is not affected by left or right hosting ideology (Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf2016a; Spittler Reference Spittler, Kneip and Merkel2018). Moreover, the rule of law is not affected by right-wing populism in government while, when it comes to political participation, populists’ electoral strength actually boosts (electoral) participation (Spittler Reference Spittler, Kneip and Merkel2018). This latter finding shows how populism can be analysed as a ‘corrective’ to liberal democracy. However, Marcus Spittler (Reference Spittler, Kneip and Merkel2018) also found that right-wing populist parties are a ‘threat’ due to their negative influence on individual liberties.

Hypotheses

As explained in the previous section, the literature has highlighted the existence of three competing hypotheses about populism: (1) populism as a threat to democracy; (2) populism as a corrective to democracy; and (3) populism as a threat and a corrective to democracy.

As this article deals with populism in government and the evidence provided so far on the impact of populism on the qualities of democracy has been mixed (see above) – yet oriented towards privileging Hypotheses 1 and 3 – I will use the first hypothesis as a point of reference to test whether populism has a negative impact on the qualities of democracy. In particular, as recent works have shown, populism negatively affects the qualities of democracy, but without causing democratic breakdown per se (Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b, Reference Huber, Schimpf, Heinisch, Holtz-Bacha and Mazzoleni2017b). Thus, I expect that:

Hypothesis 1: Regardless of the hosting ideology, populists in government impact the qualities of democracy more negatively than non-populist governments do.

However, populist parties do not always have the same role when in government, as the earlier section has shown. Populist parties have been in opposition, for the most part, but they also provide external support to non-populist governments, they have been junior and major partners in coalition governments or have governed alone or with another populist party. Different roles should have different impacts, as providing external support to a government cannot have the same impact on policymaking as being a junior/major partner or governing in a single-party government. In particular, the literature has shown that radical right junior partners were not usually able markedly to influence policies related to immigration (Akkerman Reference Akkerman2012) and that junior partners are frequently less able to deliver and are thus punished in the elections following their entrance into government (Klüver and Spoon Reference Klüver and Spoon2020). The literature on populism has not explored this issue yet, so the main general expectation is that different roles in government affect the qualities of democracy in different ways. In order to discriminate between the roles played by populist parties in each polity, I thus expect that:

Hypothesis 2: The more relevant the status of the populist party in government, the higher the (negative) impact on the qualities of democracy.

Related to this hypothesis, another aspect worth investigating is the potentially different impact of the different kinds of populism. To test it, I follow the finding in the literature on the negative impact of radical right parties (Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf2016a; Spittler Reference Spittler, Kneip and Merkel2018), here labelled EPPs. As the earlier section has shown, EPPs are not the only parties which have gained access to government: more recently, IPPs and in some cases other types of populism have entered government, such as neoliberal populism (see above) or the niche techno-populism (Bickerton and Accetti Reference Bickerton and Accetti2018) represented by the Five Star Movement. Following the literature on the negative impact of EPPs on several qualities of democracy (Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf2016a, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b, Reference Huber and Schimpf2017a; Spittler Reference Spittler, Kneip and Merkel2018), I expect that:

Hypothesis 3: EPPs in government have a more detrimental impact on the qualities of democracy than IPPs (and other types of populism).

Data and methods

Data

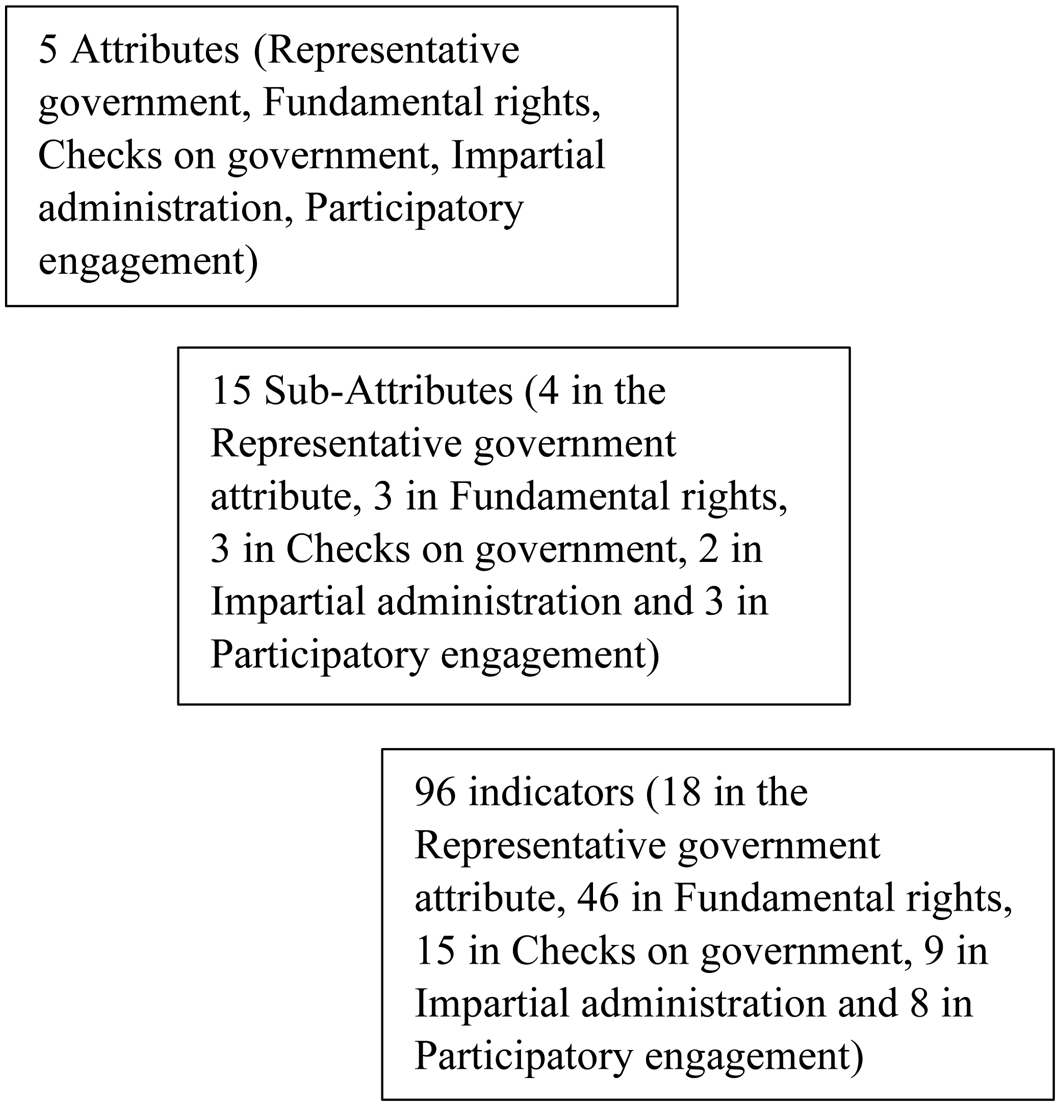

In order to assess the impact of populism on the qualities of democracy I use the GSoDI data set.Footnote 4 The GSoDI is composed of five main attributes (representative government, fundamental rights, checks on government, impartial administration and participatory engagement), 15 sub-attributes and 96 indicators. The attribute Fundamental Right has eight sub-components which in the ladder of abstraction are located between indicators and sub-attributes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hierarchy of the Source of GSoDI Data Set

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Rather than focusing solely on the five main dimensions, I select from dimensions, sub-dimensions and indicators those connected with the three main populist dimensions – that is, political representation, pluralism and participation – and those which help to distinguish the impact of EPPs and IPPs (fundamental rights). I include all the main attributes of the GSoDI, except for Impartial Administration, for which no theoretical expectations have been provided in the literature. The main attributes are composite indices, which provide a general overview of each of the four dimensions that constitute a democratic regime. Besides the four macro-dimensions of democracy, I add sub-dimensions and sub-attributes to investigate further the specific qualities on which populism in government might have a direct impact. The four main dimensions and the attributes will be divided in the empirical investigation into three broad macro-areas: political representation, pluralism and participation, and the protection of minority rights. The following paragraphs describe the indicators included in the three macro-areas.

Political representation

Along with the limited majority rule and elective procedures, the representational transmission of power is the backbone of modern (liberal) democracies (Sartori Reference Sartori1987a). Whether or not populists represent the ‘true’ people vis-à-vis the elites, the principle of (fair) representation is a conditio sine que non for the analysis of democratic qualities (Dahl Reference Dahl1971). For political representation the main proxy will be the Representative government GSoDI dimension. To this dimension, I add two indicators of the Fundamental rights attribute – Power distributed by social group and Representation of disadvantaged social groups – in order to check for the relationship between political representation and political representation of the minority groups, which in Hypothesis 3 should be negatively related to EPPs in government.

Pluralism and participation

In a liberal democratic system, there are two main aspects related to pluralism. The first is connected with the liberal concept of ‘checks and balances’, with which populism has an ambivalent relationship as it constrains in its essence the majority rule and, broadly speaking the ‘will of the people’ (Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Kaltwasser CR2014). The second is the (democratic) principle of freedom of expression, under which there should be no impediment for minorities to express their opinions (Dahl Reference Dahl1965). In this regard, the proxies used here are Checks on government and Freedom of expression (a sub-component of the Fundamental rights attribute). One positive aspect which is frequently associated with populism is the inclusion of the people in a more participatory political environment (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Huber and Schimpf2012a: 20–21). Rather than looking at the electoral turnout only, which is a proxy for political participation – but where the presence of populist parties in the political system might in itself be an incentive to participate in the election, regardless of the parties’ inclusion in government – I use the Civil society participation dimension (a sub-attribute of Participatory engagement).Footnote 5 Civil society participation measures the extent to which people are engaged in civil society activities: once in government, populist parties are expected to implement policies that foster participation within society, if populism works as a tool for the mobilization of people (and issues) (Laclau Reference Laclau2005).

Protection of minority rights

Finally, (exclusionary) populism is also believed to undermine not only political institutions but also the fundamental rights of minorities (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012a: 21–22). The protection of minority rights is the most relevant dimension that distinguishes EPPs from IPPs, as EPPs target minorities in order to limit their influence on the polity while IPPs target outgroups as the ‘people’ to be included in the in-group (Font et al. Reference Font, Graziano and Tsakatika2019; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012b).

As a proxy for the protection of minority rights, I use more than one dimension in order to check for the multifaceted aspect of this issue; a broad picture can be drawn using the Fundamental rights attribute, yet in order to be more specific about the minority rights, I add Civil liberties, which is a sub-attribute of the Fundamental rights attribute, Social group equality (a sub-component of Fundamental rights) and one indicator of the Social group equality, Social group equality with regard to civil liberties.

Modelling strategy

The first hypotheses will be tested in two steps. First, I use a time-series analysis for each indicator and for each country in order to account for the context-dependency of populism (Taggart Reference Taggart2000). The aim is to detect when structural breaks occur in the time span selected for each country. Relying on the Wilkinson–Rogers notation (Wilkinson and Rogers Reference Wilkinson and Rogers1973), Achim Zeileis et al. (Reference Zeileis2002a, Reference Zeileis2002b) created a software specification in R to test the cumulated sums of standard OLS residuals (OLS-based CUSUM test), a test first introduced by Werner Ploberger and Walter Krämer (Reference Ploberger and Krämer1992). Structural breaks occur when a time series abruptly changes at a point in time due to an event which the theory and shared knowledge need to identify. As the structural break indicates when a time series significantly changes its ‘normal’ path, in this specific case, the aim is to assess whether structural breaks occur when populist parties are in government. The coding procedure for associating structural breaks with governments in office can be found in the Online Appendix (see ‘Coding procedure for structural breaks’).

After detecting the structural breaks, I sum those which occurred during populist and non-populist governments and I derive the structural break/years in government (SB/YG) ratio. The SB/YG ratio divides the total structural breaks by the years in government (derived from the absolute values of Table 1) of populist and non-populist governments. The ratio gives the likelihood of a structural break in a temporal unit. The higher the ratio, the higher the possibility that a structural break occurs and vice versa.

The second step is focused on panel regression models, in which the dependent variable is represented by the scores of each country in each previously selected indicator. Thus, there are 10 dependent variables, whose values range from 0 to 1. The main independent variable is a dummy variable indicating whether populist parties are in government (= 0) or in opposition (= 1). To this, I add other controls. First, the GDP per capita and the unemployment rate (World Bank 2020) are intended to control for the economic performance of the countries; second, the effective number of electoral parties (ENEP) (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2019) to control for the fractionalization of the party system, which might reduce the possibility of a non-mainstream party entering government. The third control is the age of the democracy (Boix et al. Reference Boix, Miller and Rosato2013), as the consolidation of a democracy might temper the influence of populists in government. The fourth is the institutionalization of the party system (Casal Bértoa Reference Bértoa F2021) – ‘the process by which the patterns of interaction among political parties become routine, predictable and stable over time’ – as the deinstitutionalization of party systems negatively affects electoral accountability (Mainwaring and Torcal Reference Mainwaring, Torcal, Katz and Crotty2006).

To test the second and the third hypotheses, I again use panel regression models with the same dependent variables and the same controls. Unlike the second part of the first hypothesis, one independent variable is different for the second and third hypotheses: the dummy variable measuring the presence of populist parties in opposition or in government. In the second hypothesis, this variable has been replaced by the role of populist parties in government. It is a categorical variable distinguishing the role of the populist party in government: as external supporter, as junior partner(s) in a coalition government, as major partner in a coalition government.Footnote 6 In the third hypothesis, it has been replaced by the type of populist party in government. It is a categorical variable with four levels, ‘Exclusionary’ (reference category), ‘Inclusionary’, ‘Other populists’ and ‘None’ (indicating when populist parties were not included in government). For each model, I run a Hausman test to select the most appropriate model between random- and fixed-effects models.

Results and discussion

In the first step of the analysis for Hypothesis 1, I check the occurrence of structural breaks and populist parties in government. I focus specifically on negative structural breaks in order to evaluate the alleged negative impact of populism in government on the qualities of democracy. Structural breaks occur more often when populist parties are in government. In the whole period, 32 (43.8%) negative structural breaks occurred when populist parties were in government and 41 (56.1%) when non-populist parties were in government.Footnote 7

Using the data on structural breaks in Table 2 and Table 1 data on populists’ presence in government, it is possible to calculate the SB/YG ratio. Overall, the SB/YG ratio for negative structural breaks is 0.276 for populists in government and 0.009 for non-populists.

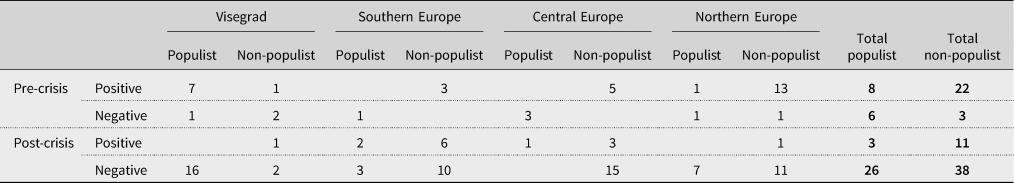

Table 2. Negative and Positive Structural Breaks for 10 Different Indicators of the Quality of Democracy

Source: Author's own elaboration from GSoDI data.

However, this figure must also be discussed dividing the pre-crisis and the post-crisis scenario (2010–18), as in the latter the percentage of populist parties in government grows substantially (Table 1). The difference is still positive, but the overall picture is less clear cut: the SB/YG ratio is 0.382 for populists and 0.311 for non-populists.

For the second step of the analysis, Table 3 reports the results of the panel regression models for each of the dimensions under analysis. The findings clearly indicate that having populists in government or in opposition matters when it comes to democratic qualities. First, all main GSoDI dimensions are significant and positive (Representative government, Checks on government, Civil society participation and Fundamental rights). Sub-attributes are significant as well: only in one case (third model, Representation of the disadvantaged social groups) is the difference not significant; when it comes to Social group equality with regard to civil liberties the significance is only at the p < 0.05 level. Whichever main dimension is under analysis, populism affects the qualities of democracy. Admittedly, the effect is lower than other control variables, such as the institutionalization of the party system. As for party institutionalization, the pattern is almost invariably stable, that is, a higher institutionalization improves the quality of the democracy. Again, the only exception is Representation of the disadvantaged social groups, where the variable is significant, but in the opposite direction. In three other cases, Power distributed by social group, Fundamental rights and Social group equality, the variable is not significant. Overall, the results of the two-step analysis support Hypothesis 1, that populist parties are more harmful to the qualities of democracy than non-populist parties.

Table 3. Panel Regression Models for 10 Democratic Qualities, Hausman tests to determine whether to use random or fixed effects for each model

Note: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1.

For the second hypothesis, Figure 3 shows the different impact of the role of populist parties in government, compared with when they were not included in the government (full model specification can be found in the Online Appendix, Table 4A). The results are mixed: in the political representation and protection of minority rights macro-areas evidence is weaker than in the pluralism macro-area. Specifically, in two cases (Representative government and Power distributed by social group) of the political representation macro-area there are non-statistically significant differences between external supporters and when populists are not included in the government, while in the third dimension (Representation of disadvantaged social groups), external supporters are the only group which differ statistically (p < 0.1). As for the protection of minority rights, on the other hand, only Civil liberties has a monotonical direction in which the more relevant the role the higher the (negative) impact. In the case of Fundamental rights, the effect of junior and major categories is almost the same. The two qualities related to Social group equality show a different pattern and, in both cases, the major partner category does not differ at the 0.001 level with respect to the reference category.

Figure 3. Effects of the Categorical Variable Populists’ Role in Government in Panel Regression Models for 10 Democratic Qualities

Note: Full model specifications are available in the Online Appendix (Table 4A).

In the four models of the minority rights protection macro-area there is no statistical difference between external supporters and the reference category. Nonetheless, the pattern is clearer for the pluralism macro-area, especially in the Checks on government and Freedom of expression dimensions. Civil society participation is, in this regard, deviant as junior partners have a larger negative effect than major partners do. In these three cases, again, there are no differences between external supporters and the reference category. Overall, the evidence points to partially confirming Hypothesis 2, even though the results are not univocal: the main dimensions of the GSoDI data set (Representative government, Checks on government, Civil society participation and Fundamental rights) indicate a clear-cut distinction between external supporters and other forms of involvement, yet the difference between being a major or a junior partner is less evident. The sub-dimensions, on the other hand, have no clear-cut pattern.

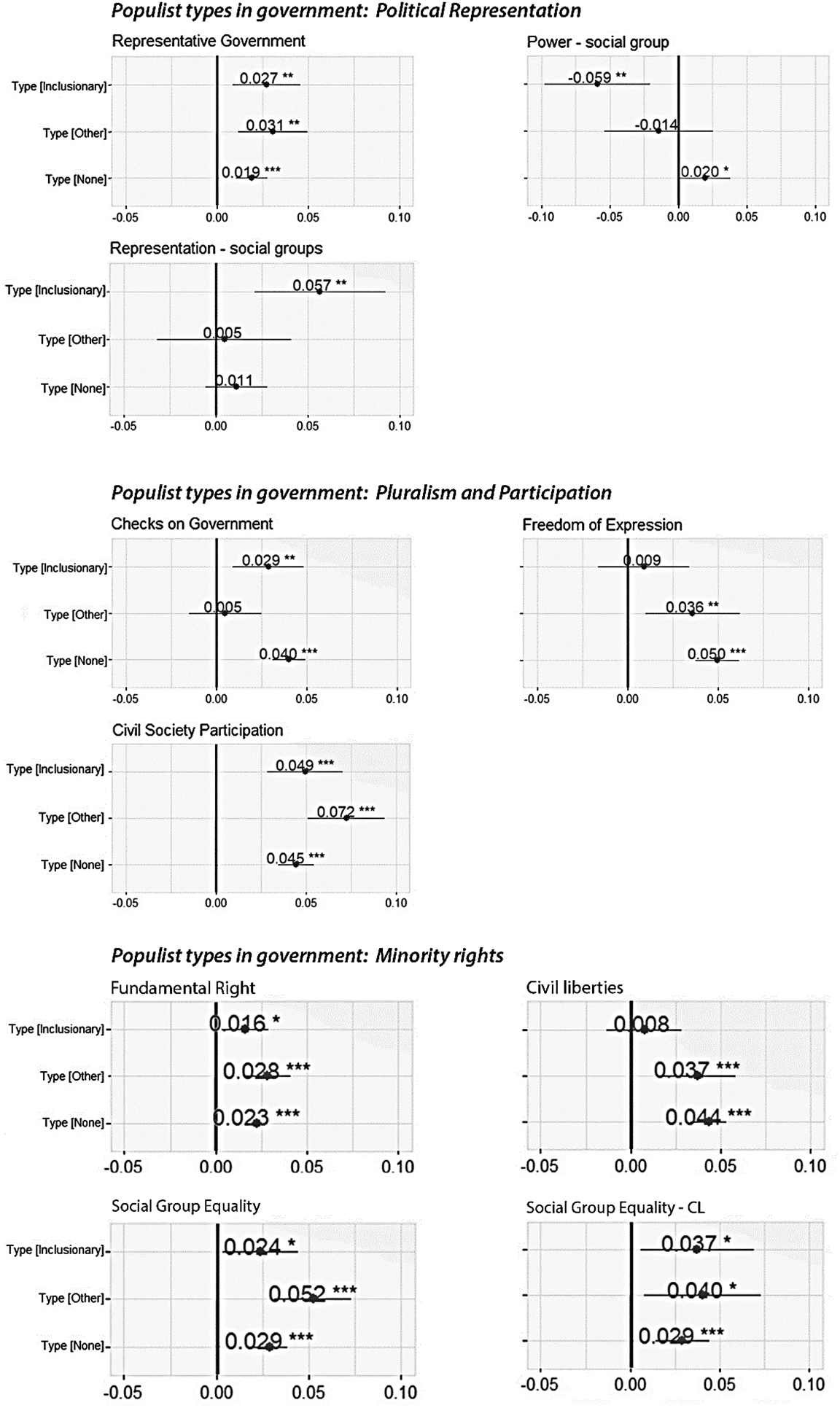

Finally, the evidence supporting Hypothesis 3 is robust, yet not univocal (Figure 4, full model specifications can be found in the Online Appendix, Table 5A). Following the empirical results for Hypothesis 1, it emerges that populist parties have a negative impact on the qualities of democracies, compared with governments with no populists. When restricting the focus to a comparison between EPPs and the ‘None’ category – that is, when populists are not included in the government – the difference is robust. Only the Representation of disadvantaged social groups category is non-significant; all other qualities are positive and significant at either the p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 levels, meaning that having EPPs excluded from government increases the qualities of democracy. A similar, yet non-identical, pattern can be found when comparing EPPs with other populist parties in government: in this case, however, the two indicators in the political representation dimension and, more importantly, the Checks on government, are not significant. Overall, populist parties in the ‘Other’ category perform far better when it comes to the minority rights protection macro-area. The main issue under investigation in Hypothesis 3 is the comparison between EPPs and IPPs: in this regard, the main dimensions of the GSoDI (Representative government, Checks on government, Civil society participation and Fundamental rights) in the three macro-areas are significant and positive. As for the other sub-dimensions, in one case the difference is significant, but negative (Power distributed by social group), in two cases EPPs and IPPs do not diverge statistically (Freedom of expression and Civil liberties) and in two others the difference is positive and significant at p < 0.05 level (the two Social group equality indicators). In conclusion, while IPPs have a more positive impact on the most relevant dimensions of democracies compared with EPPs, the empirical findings are not as strong as the ones identified in Hypothesis 1.

Figure 4. Effects of the Categorical Variable Populist Types in Panel Regression Models for 10 Democratic Qualities

Note: Full model specifications are available in the Online Appendix (Table 5A).

Conclusions

The debate about the impact of populism on liberal democracy is long-standing. In the literature, populism has been regarded as a threat, a corrective, and a threat and corrective to democracy. Starting from the most recent comparative literature on the topic, this article has addressed the question of whether populist parties affect (negatively or positively) the qualities of liberal democracy when in government, whether their role in government matters and whether specific types of populist parties, namely EPPs, have a more negative impact than other types. In order to answer these questions, I first provided a new descriptive analysis of the inclusion of populist parties in government, showing that populist parties’ electoral success in the last decade coincided with the increasing inclusion in (coalition) government of these parties. Second, using the GSoDI data set, I found strong empirical confirmation of the fact that populists in government impact liberal democratic qualities more negatively than non-populists do. Additionally, I tested the impact of populism depending on the role of populist parties in government.

The results show that role matters only to a limited extent: if populist parties are external supporters, their impact on the quality of democracy is the same as if they were not included in government. It is less clear whether being a major or a junior partner makes a difference, when compared with being in opposition: in some cases, the difference is not relevant, yet in other important democratic dimensions such as Checks on government, Freedom of expression, Fundamental rights and Civil liberties the pattern indicates that major partners impact more negatively than junior partners. Finally, I show that, while EPPs have a more negative impact on the qualities of democracies than populists in opposition and other (residual) types of populism, the evidence supporting the thesis that EPPs have a different impact from IPPs is less robust, albeit present. Overall, IPPs’ footprint on the qualities of democracy is less negative than EPPs, especially when looking at the most relevant dimensions under analysis. However, in at least three dimensions this is not the case.

These findings have important implications for the study of populism: first, among the various interpretations of the relationship between populism and liberal democracy, the ‘threat’ argument has the most solid empirical ground. This, however, might also mean that populist parties are capable of delivering, if their aim is to reverse or transform liberal democracy in Europe. Needless to say, populism is not against liberal democratic values tout court, but if the goal of populist parties is to antagonize some values of the liberal democracy, then this article shows that they have been fulfilling their aim so far. More specifically and in line with the previous literature (Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf2016a, Reference Huber and Schimpf2017a; Spittler Reference Spittler, Kneip and Merkel2018), the results show that EPPs in particular have a bigger impact than the other cases: even though EPPs are increasingly involved in government and the break of the so-called cordon sanitaire to impede these parties’ access to power is no longer taboo, their inclusion means a deterioration in the qualities of liberal democracy. This might be proof that EPPs and populists in general are the only actors in Europe capable of reversing specific aspects of liberal democracy, as more and more voters have apparently been demanding for several decades now. It might also mean that their presence in government ends up being a threat to the very essence of liberal democracy.

Supplementary material

To view the supplementary material for this article, please go to: https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.21.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme for the project ‘CURE OR CURSE?’ (grant number 772695).