‘Zrušte trafiky, volte profíky’ (‘get rid of barons, vote for professionals’), urged the candidate for the Akce nespokojených občanů (ANO, Action of Dissatisfied Citizens), Adriana Krnáčová, during her 2014 election campaign for mayor of Prague (Dolejší and Prchal Reference Dolejší and Prchal2016). Krnáčová promised to end the rule of political windbags and corrupt godfathers and recruit a group of experts to manage the city more effectively. In Italy, following a series of corruption scandals involving government officials and deteriorating city services, Virginia Raggi of the Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, Five Star Movement) became the first woman to serve as mayor of Rome. In line with party rhetoric, she promised to clean up the city (hall) by bringing in impartial experts and with them a new transparency in governance (Jack Reference Jack2016). She proclaimed that she would ‘work to introduce a new alphabet and words such as merit, transparency, legality and solidarity after years of darkness and abandonment’ (Perrone Reference Perrone2017).

This article suggests that these developments are not only examples of local colour but also exhibits of a possibly more prevalent and counterintuitive combination of two trends that are rarely connected conceptually. First, there is the long-standing push towards managerial and technocratic approaches to administrative governance, which has recently received additional tailwind from debates about big data, evidence-based policymaking and experimental policy design (James et al. Reference James, Jilke and Van Ryzin2017). At the local level, ‘smart city’ strategies, which employ information and communications technology (ICT) to open up new opportunities for addressing problems of urban governance, have spread across the globe (Grossi et al. Reference Grossi, Meijer and Sargiacomo2020). The value proposition of these approaches is that data-driven, ICT-based public sector innovations and governance approaches can be effective means to counterbalance the shortcomings of electoral politics, especially its short-termism and clientelism, as well as those of a traditional rule-based bureaucracy (Shim and Eom Reference Shim and Eom2008). While initially associated with liberal market economies, managerial reforms are continuing to spread across subnational governments, especially in areas with lower-quality governance (Meyer-Sahling Reference Meyer-Sahling2011).

The second trend is the rapid loss of ground of traditional political parties in national and local elections, especially in Eastern and Southern Europe, and the consistent rise of new leaders linked with populist parties and anti-establishment movements (Aberg and Ahlberger Reference Aberg and Ahlberger2015; Vampa Reference Vampa2016). This trend is especially visible at the municipal level. Local elections in Italy in 2016 brought the M5S to power in Rome and in 42 other large and small cities, including Turin and Livorno, while an independent candidate managed to throw traditional parties out of the race in Naples. Likewise, in Spain since the start of the financial crisis, new parties and electoral lists have won a significant portion of council seats in the 2011 and 2015 local elections. New political subjects governed directly in several cities, including Barcelona, Cádiz and Madrid (Drápalová and Vampa Reference Drápalová and Vampa2018). In 2015 and 2019, the populist party ANO won a landslide victory in local elections in Prague and celebrated success in other large cities in the Czech Republic, like Brno and Ostrava. In short, the populist waves swept through traditional party systems across all government levels and brought populist politicians into executive positions. What is especially interesting is that those local populist politicians frequently combine technocratic discourse with their populist stance.

This combination of populism and technocracy at the local level introduces a theoretical and an empirical puzzle. First, the two phenomena were, until recently, deemed radically opposed if not antagonist to each other in the literature. Second, the local level seems to be especially prone to this intersection between technocracy and populist ideology. We argue that the increasing significance of populist parties and politicians at the municipal level implies that administrative reform is becoming an arena for the application of populist political strategies. The rhetoric of technocratic governance is used to deploy elements from the populist playbook to executive politics. While populists are often dismissed as lacking competence and interest in actual governance, technocracy signals expertise to their audience.

While this could be dismissed as mere rhetoric, the actual impact of technocratic populism on executive governance might be substantive. We call this pattern ‘technocratic populism’. We draw primarily on two cases – Prague and Rome – to show that technocratic rhetoric can be part of populist electoral and political strategies at the subnational level. This strategy consists of varying combinations of populist and technocratic elements: (1) hostility to (party) politics as a foundation for urban governance and bureaucracy as part of self-serving establishments; (2) an emphasis on seemingly apolitical ‘what works’ management strategies, output effectiveness and new technologies; and (3) the detachment of the executive leader from the ‘traditional’ bureaucracy and the personalization of executive government, recruitment of leaders and executive coordination.

This article contributes to the literature in two ways. First, it contributes to the theoretical discussion on populism by exploring the intersection between populist discourse and technocratic administrative reform at the subnational level. While a select number of authors have pointed to the intersection of populism and technocracy (Bickerton and Accetti Reference Bickerton and Accetti2018; Buštíková and Guasti Reference Buštíková and Guasti2019; de la Torre Reference De la Torre2013 among others), their propositions remain rather generic. We aim to explore how the synergies and tensions between technocracy and populism are solved in the rhetoric and practice at the local level. Second, this article adopts an original and innovative subnational focus and explores technocratic populism as a political and governance strategy at the municipal level. It assesses how the interaction of populism and technocracy plays out empirically in relation to administration and public policies. Although populist parties and leaders are on the rise across Europe, the subnational level has been largely overlooked. The lack of attention to the local level is a significant limitation as – unlike their counterparts in national governments – populist leaders at the local level have governed many cities, reforming public administration (Rossi Reference Rossi2018). For example, despite worsening electoral results at the national level, following the Spanish 2019 local election results, Podemos would govern in 334 cities with an absolute majority. In the Czech Republic from 2015 to 2019, populist mayors governed in 12 of the largest cities including the country's capital, Prague. Similar results were also observed in Italy, where the M5S won elections in Rome, Turin and 41 smaller cities.

Many populist parties govern at first at this level and can play an essential role in shaping local politics, public services and administrative reform. Local experiences with populism can serve as laboratories for small-scale experiments of this populist ideology. This article aims to fill the ‘sub-national gap’ by looking at the relationship between technocracy and populist discourse in the arena of urban governance in two local governments: Prague and Rome. To our knowledge, there have been very few attempts to explore empirically the role of populist politics in executive politics at the local level (Paxton Reference Paxton2019).

The article is structured as follows: The section that follows develops the concept of technocratic populism and argues why the subnational level is relevant. In the third section, the empirical cases of Prague and Rome are used to illustrate the significance of the concept of technocratic populism. However, we also show that cases vary concerning the combination of the elements deployed in practice. The concluding section points to the potential value and limitations of technocratic populism as a concept for studying the political dynamics of administrative reform at the subnational level.

Technocratic populism: marriage of convenience?

This article focuses on an unlikely but increasingly prevalent political agenda – the combination of technocracy and populism. It explores this conceptual alliance, the strategies for executive governance and administrative reform and probable tensions between the two in practice at the subnational level. While, until recently, the two concepts were considered to be incompatible or even antagonistic (Müller Reference Müller2016), a growing body of literature suggests that there is a considerable overlap between populist ideology and the technocratic idea of governance (see Bickerton and Accetti Reference Bickerton, Accetti, Kaltwasser C, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017a, Reference Bickerton and Accetti2018; Buštíková and Guasti Reference Buštíková and Guasti2019; Caramani Reference Caramani2017; de la Torre Reference De la Torre2013; Havlík Reference Havlík2019). Indeed, especially at the local level, we can observe a political strategy that combines populist ideology and rhetoric with the appeal to efficiency and effective management through the use of experts.

The standard definition refers to populism as a form of politics that considers ‘society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 543). Although scholars discuss whether populism is a distinct ideology or a strategy (Weyland Reference Weyland2001), most agree on certain minimal common denominators: an anti-elite orientation, anti-pluralism, people-centrism (Caramani Reference Caramani2017; Müller Reference Müller2016). If populism is understood as a strategy, its content changes depending on the establishment against which it is mobilizing. Populists react to the structure of power, and their anti-elitist stance may be responding in different ways to various ideological environments; this versatility contributes to populists’ chameleon-type nature (Taggart Reference Taggart2004).

As a ‘thin’ ideology, populism adheres to remarkably different ‘host’ ideologies like nationalism or technocracy (Stanley Reference Stanley2008). A host ideology ‘determines the nature of the antagonism between the people and the elite and helps to distinguish different types of populist parties’ (Huber and Ruth Reference Huber and Ruth2017: 467). On the left, social populism emphasizes substantial state involvement in the capitalist economy, strong redistribution to the working class and the exclusion of the political and economic elite (Ramiro and Gomez Reference Ramiro and Gomez2017). On the right, exclusionary or xenophobic populism focuses on security and the exclusion of immigrants as well as ethnic and religious minorities (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2014). Some populists, however, do not fit neatly onto a left–right scale. Sean Hanley and Allan Sikk (Reference Hanley and Sikk2016) and Vlastimil Havlík and Benjamin Stanley (Reference Havlík and Stanley2015) argue for a new category of centrist populism that builds its legitimacy on increasing government efficiency, anti-corruption and performance and relegates ideology to a secondary position. Managerial or centrist populism frequently builds on ideas directly borrowed from the private sphere (Buštíková and Guasti Reference Buštíková and Guasti2019). It is within this category of centrist populism that the relationship between technocracy and populism is more prominent.

At first glance, technocracy with the emphasis on rational solutions and long-term planning administered by experts and professionals seems to clash directly with ‘emotional’ and people-centred populism. The source of technocratic legitimacy is the expertise and output performance, not a direct representation of people (Fischer Reference Fischer2009). They believe that competence and expertise are primary sources of their power (Esmark Reference Esmark2017). The goal of technocracy ‘is a political system in which the determining influence belongs to the technicians of the administration and the economy’ (Bell Reference Bell1974: 348, cited in Esmark Reference Esmark2017: 503). Technocrats revolve around an emphasis on a logical, pragmatic, ‘what works’ problem-solving approach to meeting objectives. Robert Putnam (Reference Putnam1977) described technocracy as apolitical, based on the replacement of politics with ‘technics’ and scepticism towards politicians and institutions. ‘The technocracy replaces the democratic discussion by the administration of experts and transforms the debate between proposals in the imposition of legitimized models with the idea that they are scientific and therefore true’ (de la Torre Reference De la Torre2013: 30).

While its emphasis on expert decision-making places technocracy in opposition to the populist urge to give voice to ‘the people’, technocracy's problematization of pluralism and representative democracy and its inclination for fast and clear-cut solutions resonate well with populist rhetoric. Consequently, like populists, technocrats prefer the unmediated and centralized style of policymaking, where decisions are not based on competing political factions and interests, or on direct intervention by citizens, but are a result of quick and uncontested decisions (Fischer Reference Fischer1990). These tensions also extend to the bureaucratic sphere. Technocrats blame bureaucracy, especially in the digital age, as lacking expertise, efficiency and flexibility due to its strict rule-following logic (Esmark Reference Esmark2017).

In the literature, this blend of populist elements and technocratic rhetoric as a governing strategy is called technocratic or techno-populism (Bickerton and Accetti Reference Bickerton and Accetti2017b; Buštíková and Guasti Reference Buštíková and Guasti2019; Havlík Reference Havlík2019; de la Torre Reference De la Torre2013). Christopher Bickerton and Carlo Invernizzi Accetti (Reference Bickerton and Accetti2018: 143–144) define techno-populists as ‘anti-pluralist parties with low coalition potential, that contrapose the corrupt elite and honest people and propose a technocratic conception of politics as problem-solving managerial problem orientation’. For Lenka Buštíková and Petra Guasti (Reference Buštíková and Guasti2019: 334), technocratic populism consists of the strategic use of ‘the appeal of technocratic competence and numbers to deliver a populist message. It combines the ideology of expertise with a populist political appeal to ordinary people’. This article builds on these initial reflections and focuses on technocratic populism as a strategy based on combining the opposition between the corrupt, incompetent elite and honest people, hostility to the administration (labelled as inefficient and corrupt), legitimacy based on output efficiency that leads to an exaltation of seemingly apolitical ‘what works’ management strategies and the focus on the administrative and management reform of governance implemented by ‘neutral’ experts. While technocratic populists dispense with the left–right ideological distinction, they embrace efficient management as their prism. The technocratic component presumes to deliver the efficiency of public institutions. Some of the most prominent examples of technocratic populists described are those in Italy (Bickerton and Accetti Reference Bickerton and Accetti2018), the Czech Republic (Havlík Reference Havlík2019) and Latin America (de la Torre Reference De la Torre2013).

Populism and technocracy, thus, complement each other on several fronts. Both populists and technocrats share ‘unitary, non-pluralist, unmediated, and unaccountable vision of society's general interest’ (Caramani Reference Caramani2017: 54). The anti-pluralism and bipolar division of society into two opposing camps between good people and elites, us and them, is a core component of populism. The technocratic populism frames, however, the bipolar division of society and conflict in a less nativist and more pragmatic fashion as hard-working people against incompetent and corrupt political elites. Technocratic rhetoric reinforces the nature of the antagonism between the people and the elite but bases its front line on the incompetency and incapacity of traditional politics to solve pressing social issues. In their discourse, technocratic populists target the state and the administration, which are considered corrupt, wasteful and rigid and thus responsible for poor economic and social situations (Bickerton and Accetti Reference Bickerton and Accetti2018).

While left- or right-wing populists pursue their ideological vision, technocratic populism relegates ideology to the background and instead prioritizes the efficiency, results and performance that the technocratic component claims to deliver. The pragmatic ‘what works’ becomes the new criterion for public policy. ICT tools, e-government innovations and performance management become useful tools in the hands of technocratic populists. Technocratic populism also symbolizes a different form of governance, one that would move beyond the old style of patronage, corruption, fragmentation and politicization (Paschoal and Wegrich Reference Paschoal and Wegrich2019). The intersection between populism and technocratic governance can be, thus, understood as a way to compensate for the populists’ ‘competency gap’ (Panizza et al. Reference Panizza, Peters and Ramos Larraburu2019). Populism is said to be impatient with decision-making procedures that reflect a plurality of views and are designed to forge compromises between diverse actors (Caramani Reference Caramani2017). Populists are frequently criticized for emotionality, their lack of experience, and empty rhetoric. The technocratic component fills the populist void and signals to voters the promise of expertise, competence and good management. In populist hands, technocracy becomes an excellent tool to ‘find’ the simple solutions that people need. Cas Mudde (Reference Mudde2004: 547) described this instrumental symbiosis between populism and technocracy as consisting of populists capturing people's needs and wishes, and technocrats finding solutions and implementing them effectively. Populism supplies popular legitimation to technocracy and provides the electoral channel to power.

As technocratic populists base their discourse on successful performance, they focus on the management aspect of governance. Technocracy supplies the mechanisms and tools for reforming executive governance. However, what appears to be a cold-hearted management technique within the framework of technocracy becomes part of a political mobilization strategy in the hands of populist politicians. For technocratic populists, the hierarchy, neutrality and rule-following logic of administrative action – characteristic of Weberian bureaucracy – are obstacles to quick problem-solving (Fischer Reference Fischer1990). They tend to centralize power and control and limit intermediary layers, checks and balances in the administration. The governance of these rational (technocratic) management tools is embedded in a network of personal loyalty relations as well as indirect and informal control mechanisms, which subverts the procedures of bureaucratic and wider political control (Paschoal and Wegrich Reference Paschoal and Wegrich2019). Hence, in the emerging empirical pattern of technocratic populism, argumentative justifications taken from the technocratic playbook are used to de-institutionalize administrative patterns and structures, in particular by changing public service bargains – the formal and informal institutions and understanding of roles shaping the relations between political executives and bureaucrats (Hood and Lodge Reference Hood and Lodge2006). They also impact on executive coordination by putting more emphasis on direct control and personal loyalty.

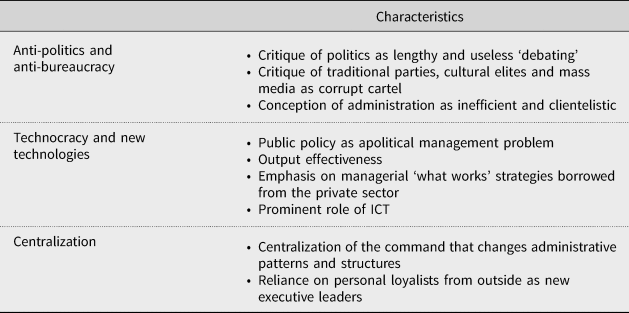

To sum up, we build the link between populism and technocracy on three levels, as shown in Table 1. The first level is the Manichaean division between corrupt elites and good people, which contains an anti-pluralism and anti-politics aspect. This aspect is framed as the opposition to cartelized political parties that are part of the self-serving establishment that must be curtailed. The second level is legitimacy based on output efficiency, which lends itself to technocratic ‘what works’ approaches and claims that management does not require politics or ideology. The third level is a focus on the administrative and management aspect of governance and the depoliticization of governance.

Table 1. Summary of the Principal Dimensions of Technocratic Populism

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Technocratic populism at the local level

Technocratic populism is not new in local politics. The progressive movement and consequent instalment of city managers in US cities is a clear example of the logic of technocratic populism (Lapuente Reference Lapuente2010). Populist and neo-populist leaders have run cities and countries in Latin America for decades. In Latin America, they aimed to depoliticize their societies by calling for ‘efficient’, market-friendly measures to allow full dedication to the private sphere (de la Torre Reference De la Torre2013; Kaltwasser Reference Kaltwasser2014; Weyland Reference Weyland2001). Clear examples of such leaders are the former mayor of Rio de Janeiro, Eduardo Paes (Paschoal and Wegrich Reference Paschoal and Wegrich2019), the former mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg (Brash Reference Brash2011), and even Boris Johnson (Barber Reference Barber2014), formerly mayor of London, UK.

Technocratic populism is particularly fitting for the local level, for two reasons: First, the nature of political representation at the municipal level is much more direct, personalized and unmediated. At the local level, political representatives are in much closer and direct contact with citizens. Mayors especially are at the forefront of public life; they attend many public meetings and events and they personally claim the benefits of particular policies. This exposure makes local politics much more personalized. Public exposure is exceptionally high in the case of strong and directly elected mayors. Even in more collective forms of local government, the mayor is a prominent political figure and representative. This unmediated political style at city level fits populist leaders exceptionally well. Indeed, many renowned populist politicians are or have been mayors. Moreover, urban governance is increasingly less party-dominated. Traditional mass parties are losing ground, especially in medium-sized cities in Europe, a broader trend that is particularly prevalent in Eastern and Southern European local governments. It manifests in a large share of independent candidates (the Czech Republic), local movements and neighbourhood groups (Spain and Italy) that build specifically on their direct connection with the local population.

Although the unmediated nature of local politics is an opportunity for populist politicians, cities are also the place where delivery and performance matter most. At the local level, politicians have to implement policies and deliver services, and thus mayors have to be able to show a certain level of expertise. The local level is often perceived as the realm of administration, rather than the realm of politics, where technocratic solutions to policymaking find fertile ground. Cities represent the level of government that delivers the majority of public services and implements public policies decided at higher levels. According to Benjamin Barber, the local, pragmatic problem-solving character of the office of mayor seems to override differences in the political landscape, ideological intensity and the formal method of governing. He suggests that cities have essential features that trump the usual political and ideological factors which otherwise shape and constrain politicians (Barber Reference Barber2014: 109–110).

Municipal governments engage less with re-distributive policies that are inherently political and deal more with the effective distribution of resources previously decided at higher levels. The emphasis on implementation creates additional pressure on local politicians’ competence. At the local level, pressure to deliver and implement the agenda is much higher. Citizens perceive a more direct link between politicians and local government performance. Hence, the mayor's competence is a relevant factor that voters pay attention to during elections. Populist politicians try to overcome this challenge by using apolitical and technocratic expertise that should mobilize all their means to deliver.

Urban governance also provides favourable contextual conditions for populism to develop. Many current political, economic and social conflicts and crises (refugee or environmental crises) materialize here and local administrations are first and foremost dealing with those ‘wicked’ problems. Populist politicians can use these conflicts to their benefit – for example, in concerns over the provision of public goods for refugees or migrants. Indeed, more authors now point to the territorial roots of populism (Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2017) and subnational political and economic divergence. For all these reasons mentioned, more research is needed on how technocracy and populism are playing out at the local level.

Empirical illustrations of technocratic populism

This article compares populist governments in two European cities, namely Prague in the Czech Republic and Rome in Italy. Both Prague and Rome are, or were, governed by mayors from populist parties; ANO governed in Prague and the M5S in Rome. We focus on large capital cities, as they tend to share many relevant characteristics despite being located in different countries (Sassen Reference Sassen2000). They also serve as illustrative examples of trends already present in these countries, allowing for a comparison between different countries and administrative systems. Our case selection was informed by several criteria that have been identified in the literature as factors associated with populism: institutional setting (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser C2017), party system competition, past government performance (Agerberg Reference Agerberg2017) and economic situation (Taggart Reference Taggart2004). These factors were taken into account in the case selection of Prague and Rome.

Both cities share very similar characteristics (capital cities, local party system collapse, previous poor management, female leaders); at the same time, they are examples of different local government institutional organizations. The dynamics of party politics and past government performance play a role in the success of populist political candidates. Previous poor management and corruption scandals certainly play into the hands of populist leaders (Agerberg Reference Agerberg2017). Prague and Rome are clear examples of this trend. In both cities the rise of populist leaders is associated with previous political parties’ corruption scandals, a difficult economic situation and wasteful mismanagement of public utilities. In both cases, the local leaders are female, with limited previous experience in politics. Regarding the institutional setting, the literature argues that presidential systems strengthen personalized leadership while parliamentary systems incentivize the existence of political parties (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser C2017). Adapted to the local level, it is unlikely that there is much space for populist leaders in places with more collective forms of local government (such as Swedish municipalities). We thus selected our cases from Eastern and Southern Europe, where political leadership tends to be personalized. Our cases represent two variations of local government setting: a committee form of government, in which mayors are indirectly elected (Prague), and a directly elected strong type of mayor (Rome) (Mouritzen and Svara Reference Mouritzen and Svara2012).

We analysed local and national newspapers and city government documents in the original language as well as secondary literature such as academic publications and speeches as reported in the media. A review of local newspapers was carried out from July 2014 until the end of 2019. For both cases, we were also able to conduct our research in the local language. We have focused on both party leaders’ public discourse, formal policy statements by the leaders and legislative behaviour. For each case, we outline the local populist party's and the local government's main characteristics; we then trace the discourse and changes made since the populist mayor was in power. Following the argument and theoretical framework, we explore our cases further by focusing on the varying combinations of the following elements: (1) the anti-establishment and anti-pluralism rhetoric of local leaders; (2) the focus on output efficiency and apolitical ‘what works’ strategy; and (3) the executive leader's detachment from the ‘traditional bureaucracy’, the centralization and personalization of executive government and the recruitment of ‘experts’.

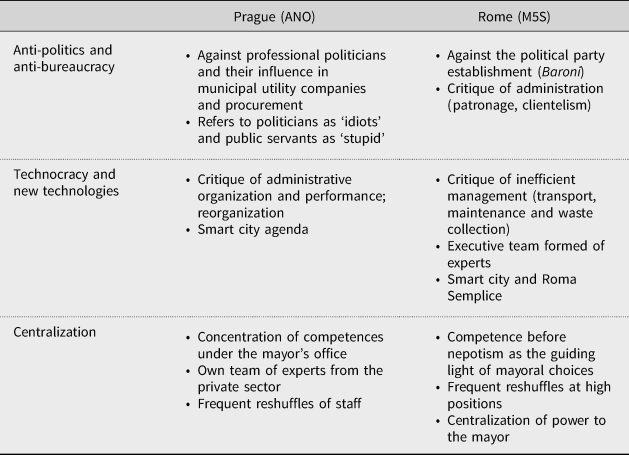

It is necessary to mention that we do not aim for the representativeness of our sample, nor do we test causal claims; however, we use the cases of Prague and Rome as examples and illustrations of our argument. We selected the cases both as instances of tendencies that are present in both countries and to provide broader insights into the phenomenon of populism. We opted for the study of large cities for pragmatic reasons, as it is more challenging to collect information from media and academic sources for smaller, less visible cities. Therefore, we do not claim that a similar phenomenon is not present in small cities. Indeed, previous analysis of populist parties in Italy shows that the M5S thrived more in smaller cities in the south (Vampa Reference Vampa2016). Our two cases thus help us to illustrate patterns in contemporary populism across as well as within European states. Table 2 summarizes the cases selected in terms of the three principal dimensions of technocratic populism.

Table 2. Prague (ANO) and Rome (M5S) Along the Principal Dimensions of Technocratic Populism

Prague: ANO and Adriana Krnáčová

In the 2014 local elections, the populist party ANO repeated the electoral success it had at the national level and swept across the country, winning the three largest cities of the Czech Republic: Prague, Brno and Ostrava. In Prague, ANO formed a quite heterogeneous coalition with the Triple Coalition (the Green Party, STAN, and the Christian and Democratic Union) and the Social Democratic Party, ending the long rule of liberal parties in the Czech capital. The decline of traditional political parties and the rise of ANO in Prague was mostly due to numerous corruption scandals involving allegations of bribery and business–government collusion in public utility contracts and procurement that led to massive debts and unfinished investment projects. ANO nominated the former Transparency International executive director, Adriana Krnáčová, as the mayoral candidate. Originally from Slovakia, she became the first female mayor of Prague. In her policy programme (not announced until after the election) she promised to focus on transparency and anti-corruption as well as the simplification of Prague's public administration: ‘I will bring together a team of experts who are able and willing to manage the city efficiently, economically, transparently so that the citizens of Prague do not have to be ashamed of their municipality and be proud that their city is flourishing, vital and that the Wenceslas Square is clean’ (Šeliga Reference Šeliga2018).

The flagships of the ‘new style of governance’ were the promises to implement smart city technology and the use of experts to economize and speed up administrative processes.Footnote 1 Krnáčová proposed that municipal companies should be run by managers from the private sector, and not by politicians as they had been previously. The campaign slogan of ‘Get rid of barons, vote for professionals’ directly alluded to the need to replace politicians and politicized bureaucrats with competent private sector managers (Dolejší and Prchal Reference Dolejší and Prchal2016).

ANO is currently the largest populist party in the Czech Republic and its leader, Andrej Babiš, is the prime minister. The party is classified as centrist in its specific brand of populism (Císař and Štětka Reference Císař, Štětka, Aalberg, Reinemann, Esser, Stromback and De Vreese2016). Founded in 2011 by Andrej Babiš, the second wealthiest Czech entrepreneur, ANO repeatedly refers to the ‘hard-working people’ and attacks the ‘lazy’ political elite. According to Buštíková and Guasti (Reference Buštíková and Guasti2019), ANO's political discourse fits into the technocratic-populist category. Its leadership is entirely concentrated in Babiš. ANO's discourse pits an ineffective and corrupt political elite against the industrious people. Its campaign slogans illustrate this distinction: ‘We are a movement of people against political elites! Vote for us, we are one of you!’, ‘We are not like politicians. We work hard.’ In line with the technocratic strategy, Babiš presents himself not as a politician but as a successful entrepreneurial CEO able to select good managers. Moreover, ANO's conception of government consists of substituting politics and deliberation with the rational management of the firm.

Local populists: us against them

Following the party line, Krnáčová has adopted ANO's strong anti-party rhetoric framed as the opposition between lazy politicians and hard-working people. The conception of Prague's local politicians as incompetent and corrupt, and ANO as competent, management-oriented and as representing ‘the people’ was captured in the campaign slogans: ‘Prague is run by idiots! We will get rid of the godfathers! A functioning team at the City Hall, we'll just build it! Better life in Prague? ANO will deliver it!’Footnote 2 From the beginning, Krnáčová presented herself as a successful CEO and distanced herself from professional politicians, which she described in interviews as lazy, incompetent and too emotional. ‘I am not an experienced politician, but a manager who presents results once policies are implemented’, declared Krnáčová to the media on numerous occasions (Prokeš Reference Prokeš2018).

Technocracy and output efficiency

ANO's programme, in general, is based on the promise to substitute management for politics, to ‘manage the state as a firm’, as party leader Babiš has repeatedly stressed. Krnáčová affirms this view of politics as a management problem: ‘I do not have time for politics, I'm a manager’ (Čapková and Otto Reference Čapková and Otto2015). As a suitable political solution to economic, social and political problems is apparently nowhere to be found, what is needed is a rational managerial approach: a technocratic formula that will streamline the functioning of public administration (Císař and Štětka Reference Císař, Štětka, Aalberg, Reinemann, Esser, Stromback and De Vreese2016). According to Krnáčová, with her own comparison:

If you take the [party electoral] programme as a recipe for a sirloin [svíčková] or cabbage soup [kapustnice], it always depends on who cooks it. You can have a great recipe and excellent raw materials, but when a stupid chef cooks, the result can be disgusting. But if you have a good chef, he or she can cook a delicious meal. We [ANO] bring good chefs, so that people in the restaurant enjoy a good meal and feel good. (Oppelt Reference Oppelt2014)

Despite Krnáčová's accentuation on competency and effective delivery, during her term in office, visible results were limited. The debt of the capital decreased from 32.67 to 20 billion Czech crowns. She opened a large complex of road tunnels in Prague; its construction was repeatedly delayed. Prague regained ownership control of strategic semi-public municipal companies such as Prague's services, water supply and the sewage system, and the company that deals with Prague's street lighting (Bereň Reference Bereň2018). An important component of Krnáčová's agenda was the technological upgrade of the city administration, especially e-government and the smart city agenda (Smart Prague), intended to simplify administration and improve communication with citizens. In Krnáčová's own words, ‘We will put a great deal of emphasis on the field of ICT … The system and the procedure for internal audits should also be changed’ (ČTK 2015). Referring to the need for a data platform that focuses on city management and planning, Krnáčová explained: ‘We live in the 21st century, and I find it totally absurd that people have to still do everything personally in an office’ (iDNES.cz 2016). In 2018, Prague's government launched the city data platform which should centralize data for the better management of municipal services. Other pressing issues like infrastructure projects, Metro line D and public transport were not settled.

Redrawing the city hall

Shortly after assuming office, Krnáčová declared that she would aim to increase the accountability of civil servants so that the administration would become professional and efficient, providing a user-friendly service to the citizens and visitors to Prague. She remarked, ‘The current administrative structure of the city hall is inappropriate. The administrative reorganisation eats up a third of my time because no one was taking care of the poor thing [the municipal administrative structure]’ (Aktuálně.cz 2015). As mayor, Krnáčová initiated the reorganization of executive boards of most of the city's companies, merged several city hall directorates and agencies, and made numerous management-level personnel changes in the city hall administration.

On the one hand, Krnáčová has proposed the rotation of municipal staff and implementation of the ‘four-eye’ principle – that signatures of more than one member of staff are needed on essential documents – and that the boards of municipal companies are staffed with managers who have no links to political parties. On the other hand, Krnáčová aimed to gain more direct political control, adding under her direction several large agendas such as the legislative and IT departments as well as the commission controlling public procurement (Oppelt Reference Oppelt2017). Despite her promises, municipal companies were filled with ANO and coalition parties’ political appointees (Lidové noviny 2015). In 2015 Krnáčová announced additional shake-ups to the administration. These included the creation of a new directorate dealing with public relations and the merging of local agencies; she transferred core competencies into a single directorate and reorganized the city's information technology department, and an employee audit. Under her direction, the new municipal government merged and redistributed sections, abolished one control level and modified the system of audits (Pražský deník 2015).

Krnáčová also initiated some controversial personnel changes on a broader scale, such as dismissing the leadership of the Prague Institute for Planning and Development (IPR), which is responsible for spatial planning and urban strategy. According to the mayor, the IPR had seized crucial competencies and frequently blocked the decisions of the municipal government. Having reclaimed these competencies for the city council, Krnáčová effectively disabled the IPR from blocking and fighting with the city hall. She also dismissed the director of the Prague Public Transport Company, something for which she had ferociously criticized her predecessors (ČTK 2016). A city councillor from the Pirate Party complained in an interview:

She dismissed the head of the transport company and appointed her own man without a proper open tender as if Prague was another branch of Babiš's private company … Among her other failures are: She assigns her personal loyalists and political allies to important positions … suspicious public procurement without a proper tendering process (accounting system, Christmas markets and waste collection …). (Oppelt Reference Oppelt2016)

Ultimately, the gap between the discourse and the lack of real results, personnel and internal conflicts made ANO lose the following election. In 2018 Krnáčová announced that she would not stand again as the ANO's candidate. In the 2019 local elections, ANO lost despite the new candidate building his campaign on the excellent management skills and direct (telephone) contact to Babiš. The Pirate Party governed Prague from 2019.

Rome: Virginia Raggi and the M5S

Italy's capital and most populated city, Rome, has a troubled history of poor management and corruption. The city is burdened by high debt, and its infrastructure suffers from chronic under-investment. Rome's dangerous road conditions, fleet of obsolete public buses and inefficient waste management have all made it to the front pages of international newspapers. Gianni Alemanno, mayor from 2008 to 2013, was allegedly involved in the Mafia Capitale scandal. His successor, Ignazio Marino, was forced to resign after an alleged personal finance scandal (Povoledo Reference Povoledo2016). Thus, it was no surprise when the M5S member Virginia Raggi, then a 38-year-old lawyer for the M5S, running as the anti-establishment candidate denouncing corruption, won in 2016 with almost 70% at the run-off, the largest margin in the city's history.

Since its founding in 2009, the M5S has been seen as a ‘post-ideological’ protest and populist party that gives voice to disaffected Italians who are attracted to its vehement opposition to corruption and crony capitalism (Bordignon and Ceccarini Reference Bordignon and Ceccarini2013). It started as local movements running in local elections first, and achieving a major electoral breakthrough at the national level in 2013. The M5S built its agenda on two propositions. The first is a sharp critique of Italian political parties and politicians who are blamed for Italy's poor economic performance, corruption and crisis. The M5S thus claims that competence rather than ideology should rule Italy. The second quite innovative proposition is that ‘government should take advantage of the internet and embrace technology and e-democracy as universal remedies to current democratic malady’ (Borghese Reference Borghese2017). The M5S maintains that by digitizing government, Italy will be able to tackle the problems of tax evasion, corruption and slow procurement and would increase efficiency in the public sector (Lanzone and Woods Reference Lanzone and Woods2015). These two propositions were also at the core of the party's programme for the 2016 municipal election in Rome.Footnote 3

Anti-party and populist stance

From day one of her mayoral campaign and following the general party line, Virginia Raggi adopted a highly denunciatory stance towards political parties, criticizing them for their ineptitude, corruption and self-interest. Raggi appeared very critical of both professional politicians and the media, calling them ‘casta’ (political slang for a class or elite group that intends on retaining privilege and power):

I was struck on the first day of my mandate when I saw the various politicians in the council, chatting with and greeting each other. It was a bit like when classmates meet again after the summer holidays. Right, left, centre … in fact, they have always had a tacit agreement among them. … They are part of a single system. … I prefer the pact with the citizens. (Spena Russo Reference Russo G2016)

She frequently highlighted her political inexperience and her likeness to the ordinary citizens and inhabitants of Rome. Raggi and the M5S in Rome avoided all ideological labels. Instead, they pointed to pragmatism and emphasized competent technocratic management. She claimed to prefer competence to nepotism as the guiding light of her choices building the team of city councillors (Povoledo Reference Povoledo2016).

Technocratic competency and expertise

In her inaugural speech Raggi declared: ‘This is a new era and we are in charge! We will work to restore legality and transparency in the institutions’ (Santarpia Reference Santarpia2016). Compared with the national-level strategy of the M5S, which aimed to bring ordinary citizens into parliament, Raggi followed a radically different tactic in Rome. Raggi did not select her executive team based on political affiliation but on expertise. The M5S was represented only by the mayor and deputy mayor, while specialists and technocrats held the remaining positions in the local government as well as all leading administrative positions (Bordignon Reference Bordignon2016). Some of these individuals were specialists who had been active in the city for years, whereas others were national experts in specific policy areas. Many had been visible figures in various public organizations and the private sector or academia, or were judges (Sina Reference Sina2016b). Their expertise was to ensure that problems would get fixed, and their lack of political affiliation reinforced their independence. They should, in theory, have been able to act with unprecedented freedom from political parties, or citizens, and been accountable directly to the mayor. Nevertheless, several of these experts and independent academics left as quickly as they came due to tensions with the M5S leadership; some were engulfed in corruption scandals.

The second pillar that should help Rome to achieve efficiency, transparency and financial sustainability was technological innovation and e-government. Perhaps more faithful to the M5S proposal to leverage the potential of ICT, in Rome the government put a strong emphasis on the use of ICT for improving public services and communication with citizens. Raggi created a new directorate called Roma Semplice (Simple Rome), in charge of simplifying and opening the capital's administration via e-government. Early on, the councillor responsible for Roma Semplice (Flavia Marzano) announced an ambitious plan including not only the introduction of an online public identity system and online access to services, but also the creation of a ‘single operations centre’ for day-to-day and emergency management of the city and the development of a single communication interface between private and public administration (Sina Reference Sina2016a).

In 2019, the progress of the ambitious digital plan that aimed to transform Rome into a ‘European laboratory of Innovation’ was timid. By the end of 2019, 66 municipal services were accessible online with a personal digital identifier, and several were added to the national system for online payment (PagoPA). The city made some progress in data publication and in connectivity of IT systems within municipal administration. In 2019, the municipality launched its first participative budget scheme allocating over €20 million for projects related to urban aesthetics proposed by citizens. According to municipal information, fewer than 17,000 citizens voted in the final stage and the most voted-for project received just over 3,500 votes.

Focus on management: centralization of command

‘Rome's administrative machine was stuck or worked under a flawed logic known to everyone,’ Ms Raggi said, explaining that her staff were trying – almost from scratch – to restore a law-based system for public bids and other municipal services (Pianigiani Reference Pianigiani2017). Raggi also aimed to re-engineer and reorganize the administrative machine to make it cleaner, faster, cheaper and more efficient. She announced after four months in office her plan to reform the administrative machinery and the city's macrostructure: ‘[It will be] a reorganisation of operations of the city's structures in the name of merit, transparency, [and] productivity, producing innovation and savings’ (Sina Reference Sina2016c). She declared to the media:

There is medium-term work to be done to simplify and standardize procedures [in the city]. We must … digitize procedures and eliminate paperwork … [and] increase the transparency not only of accounts but also of contracts, which must be accessible to everyone. We will make unique, centralized physical and telematic administrative access points, managed directly by the municipality and not by cooperatives and companies … The bureaucratic machine must be reorganized: there are offices with 800 people and others with four. We will start a staff reallocation, with closures and unifications. (Metro News 2016)

Under Raggi's plan, civil servants should rotate, and new departments would emerge that would be under the direction and expertise of managers. To prevent corruption, departmental leaders and employees would be re-selected. More specifically, and for the same purpose, the rules for hiring managers for the central and territorial structures of the municipal administration would be modified as required by the law (Sina Reference Sina2016b). In 2019, Raggi declared the reorganization of administration was concluded, and proceeded with large-scale hiring of civil servants. Most importantly, in the same year, Raggi announced a major reshuffle of her executive team. Four ‘technocrats’ left Rome's executive to make room for councillors with a clear political profile and loyal to the mayor. She justified this change:

Thanks to the work of ‘technical’ assessors, in these three years we have put in order the accounts of Rome, which we had found to be in a disastrous condition. We have set up a working method based on transparent awarding of contracts, thanks to which citizens can be sure that the best company on the market will win. At this stage we want politics to take the reins of the government of our city. The contribution of the ‘technical’ assessors was important; now we need a political snap. (Fatto Quotidiano 2019)

Raggi reinforced her grip on power by naming personally loyal people. Already in 2016 Raggi was criticized by the media for filling top posts with collaborators who had been associated with the administration of a previous mayor, Alemanno (Bordignon Reference Bordignon2016). Among those recently dismissed was the councillor for Roma Semplice, the architect of Digital Agenda for Rome, Flavia Marzano. Raggi assumed her agenda directly (D'Albergo Reference D'Albergo2019). That same year Raggi requested the central government to change the law and increase her competencies and executive powers with a governmental decree. This accumulation of power and leadership replacement (assessori), reaching 19 in total within three years (2016–19), shows, as in the case of Prague, tensions between the technocratic and populist components and seriously questions the long-term viability of this populist strategy.

Conclusions

This article has explored the combination of populist rhetoric and technocracy in the governments of two European cities. It argues that the increasing presence of populist politicians at the municipal level implies that administrative reform is becoming an arena for the application of populist political strategies. The technocratic rhetoric and expertise cover and implement the populist elements applied to executive politics. We call this pattern technocratic populism and draw on two cases to show that technocratic administrative reform can be part of a populist electoral and political strategy. We identify the following as the core elements of this strategy: (1) anti-politics and pluralism; (2) an emphasis on seemingly apolitical ‘what works’ management strategies, output effectiveness and new technologies; and (3) the detachment of the executive leader from the ‘traditional’ bureaucracy and the personalization of executive government, recruitment of leaders and executive coordination.

We consider the concept of technocratic populism a useful conceptual tool to analyse the political strategies of urban leaders and thereby re-introduce politics into the analysis of urban governance. It brings to the forefront the political dimensions of what at first glance might appear to be purely technical and administrative changes that accompany public sector innovations being implemented in a city. The technocratic component might be an excellent smokescreen as it is supposed to increase efficiency and implement a style of governance different from the previous corrupt and politicized governments (Paschoal and Wegrich Reference Paschoal and Wegrich2019). This management style, depicted as an apolitical approach to delivering public services, brings business-inspired tools and procedures into city halls. These political leaders describe themselves as municipal managers or CEOs. In Prague, consultants and managers of private companies became leading actors in the administration, local public agencies and companies. They were given enough space and personal support from the mayor to implement the desired reforms. Likewise, Rome followed suit, despite the national party rhetoric, the technocratic trend staffing the executive team with experts. In 2019, after severe implementation problems, Raggi shifted her strategy, opting for more political and loyal people and advisers.

Technocratic populism is distinct from other local phenomena like local lists (Drápalová and Vampa Reference Drápalová and Vampa2018) as well as from the radical left- and right-wing populist parties (Ivaldi Reference Ivaldi2018; Ramiro and Gomez Reference Ramiro and Gomez2017). In contrast to local lists, technocratic populists do not limit themselves to only one local sphere. Technocratic populism builds its distinctiveness from left and right populism by an absence of ideological anchor, and apolitical and pragmatic solutions to current problems and output legitimacy. Technocratic populism claims its own policy space and policymaking style. As this populist strategy engages closely with the administration, its effect is potentially significant. Nonetheless, we have also discovered, through our cases, that this strategy runs into deep tensions between the technocratic and populist elements. In the two cases assessed, technocratic populism eventually gave way to a variation of patronage and personal loyalty. In Prague, ANO lost power and in Rome the M5S radically changed strategy. Future research should delve deeper into how tensions between the two are resolved in practice.

We do not claim generalizability of the findings or representativeness of the two cases. Instead, we are using Prague and Rome as illustrations of technocratic populism. In this sense, the two cities are rather heterogeneous cases to compare: one in Eastern and the other in Southern Europe, one with an indirectly elected mayor and the other directly elected. On the other hand, the two cases have many similarities: both capitals have experienced corruption scandals and poor fiscal performance, and both are presided over by women and relatively politically inexperienced leaders from populist parties. Moreover, large cities are also barometers of the general situation in the country, and global cities tend to face similar challenges. Although we focused on the local level, the recent evolution in Italian and Czech national politics – where technocratic prime ministers lead populist governments – shows that technocratic populism is widespread.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank participants of the workshop ‘Democratic Backsliding and Public Administration’ hosted by RSCAS (European University Institute, Florence) for the very helpful discussion of our paper. Many thanks also to the three anonymous reviewers who provided productive feedback, comments and suggestions. Kai wishes to thank Simone Dudziak for superb editing and Kutsal Yesilkagit for support and encouragement. This article is the result of a common undertaking; both authors jointly developed theoretical framework and conducted empirical research.