In many democracies, electoral shifts since the turn of the 21st century have forced large mainstream political parties to choose between two evils if they want to govern: either reach across the aisle and form a grand coalition with a traditional arch-rival party or form a coalition with a populist, protest or niche party that has little or no governing experience. Germany has seen the first solution since 2005, with the Christian Democrats preferring to govern with the Social Democrats rather than govern with the right-wing Alternative for Germany. Similarly, following the Irish 2020 general election, traditional rivals Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael contemplated governing together to avoid either of them having to govern with Sinn Féin. Other countries have experienced the second solution, thus bringing into government, for example, the Freedom Party (2000) in Austria, SYRIZA in Greece (2015), the Five Star Movement in Italy (2018) and the Progress Party in Norway (2013). The political movements these populist parties represent have thus passed the final institutional hurdle ‘inwards toward the core of the political system’ (Rokkan Reference Rokkan2009: 79).

Political scientists have examined many aspects of the growing influence and new roles of populist parties (Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017). Some have studied why and when populist, protest and niche parties join government (Dumont and Bäck Reference Dumont and Bäck2006); others have looked at how governing affects these parties’ electoral gains and losses, ideological changes and intra-party developments (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016; Arter Reference Arter2010; Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2008; McDonnell and Newell Reference McDonnell and Newell2011). However, as emphasized by B. Guy Peters and Jon Pierre (Reference Peters and Pierre2019, Reference Peters and Pierre2020), Bert Rockman (Reference Rockman2019), and Gerry Stoker (Reference Stoker2019), practically no systematic knowledge exists about how including populist parties in government affects governance, and they call for such studies.

This article heeds the call and contributes by taking up the research question: how is government affected by the inclusion of populists? More precisely, we study effects on governance capabilities (e.g. the expertise of executive politicians), cabinet decision making (e.g. the emphasis placed on collegial bodies), political–administrative relationships (e.g. contact patterns and work relations) and communicative concerns (that is, executive politicians’ concerns about how their party, the government and the bureaucracy are portrayed in the media).

Theoretically, we approach the research question from two perspectives. In the normality perspective, the assumption is that governing has a normalizing/mainstreaming effect (Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2008; Muis and Immerzeel Reference Muis and Immerzeel2017; Tepe Reference Tepe and Thompson2019) and that executive politicians from a populist party therefore behave like those of any other party when in government. In the exceptionalism perspective, by contrast, populism does carry over to governing, and/or mainstreaming will not occur: a populist party maintains its exceptionalism, even in government, and will therefore be a different adversary for the political–administrative establishment. Whether the normality or the exceptionalism pattern dominates when populists are included in government therefore has important consequences for the functioning of government and public administration in democratic societies (Peters and Pierre Reference Peters and Pierre2019, Reference Peters and Pierre2020; Rockman Reference Rockman2019; Stoker Reference Stoker2019).

Empirically, this article uses survey data obtained from junior executive politicians (political advisers and state secretaries) from three long-lasting Norwegian governments covering the period 2001–20. In all, the 282 respondents represent seven political parties, one of them a populist party (the Progress Party). We compare the opinions, behaviour and experiences of politicians from populist and non-populist parties.

The results suggest that in Norway, ‘normality’ describes the effect of including populists in government more accurately than does ‘exceptionalism’. Populists in power nonetheless stand out by placing more emphasis on the party and less emphasis on the bureaucracy than non-populist politicians do. That populists in this research context belong to a relatively well-established party suggests that some degree of exceptionalism is a feature one should expect to find in practically all populist parties that attain power. We discuss the generalizability of the findings further in the conclusion section.

Populism and populist parties

The essence of populism is about society being divided into two antagonistic groups – the pure people and the corrupt elite – and populists believe politics should be an expression of the virtuous people (Mudde Reference Mudde2004). Although populism is a contested concept, most scholars seem to agree that people-centrism (virtuous people) and anti-elite orientation (corrupt elites) are defining characteristics (Müller Reference Müller2016). In addition, anti-pluralism is considered an essential feature: The people are morally good and their will is easy to identify but, crucially, that will can only be represented by the populist (Müller Reference Müller2016). The political and bureaucratic elites are corrupt and will therefore disrupt the will of the people.

Even though populists have anti-party sentiments, they are not against political parties, only the established parties (Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 546). Hence, populist parties – that is, political parties that adhere to and signal the thin ideology described above – have become important players in Western European party systems. The populist parties have received vast scholarly attention since the 1980s with emphasis placed on their electoral manifestos (Albertazzi and Mueller Reference Albertazzi and Mueller2013; Font et al. Reference Font, Graziano and Tsakatika2021), on explaining their electoral performances (Van Kessel Reference Van Kessel2013) and on analysing the populist voters (Brils et al. Reference Brils, Muis and Gaidytė2020; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Rovira and Andreadis2020; Voogd and Dassonneville Reference Voogd and Dassonneville2020).

Despite having entered parliamentary politics several decades ago, populist parties have only relatively recently been included in governments. So far, studies of populist parties in government have focused on the electoral costs of governing and on intra-party developments (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016; Bolleyer et al. Reference Bolleyer, Van Spanje and Wilson2012; Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2008; Van Spanje Reference Van Spanje2011). Recently, some light has been shed on decision making in populist cabinets (Baldini and Giglioli Reference Baldini and Giglioli2021) and on populist leaders’ attempts to transform the bureaucracy (Bauer and Becker Reference Bauer and Becker2020). Populist parties as equal or junior coalition partners remain under-examined, though, and the present article thus fills a gap. Generally, investigating populists in government is an important contribution to the study of populist politics, as populism is too often considered an opposition phenomenon. As Jan-Werner Müller writes, ‘[t]he notion that populists in power are bound to fail is … an illusion. … [W]hile populist parties do indeed protest against elites, this does not mean that populism in government will become contradictory’ (Müller Reference Müller2016: 42). Next, we build on earlier work on populist parties and discuss in more detail populists’ relation to governing. We depart from two main theoretical perspectives on the inclusion of populist parties in government: normality and exceptionalism.

Populists entering government: normal or exceptional?

The normality perspective departs from the notion that including populist parties in government has a normalization effect on them (Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2008; Muis and Immerzeel Reference Muis and Immerzeel2017; Tepe Reference Tepe and Thompson2019). The reasoning is that in one key sense populist parties are like, for example, parties with ties to the environmental movement of the 1970s, the peace movement of the 1960s and the labour movement in the late 19th century: huge responsibilities and tight interactions with coalition partners and the permanent bureaucracy have sobering and socializing effects on the party and its representatives. Individuals who enter the cabinet soon cast off outsider and protest sentiments they held while in opposition (Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2008). First-timers will often want to portray themselves as credible and responsible in order to establish a reputation for competence in office (Elias and Tronconi Reference Elias and Tronconi2011; Heinisch Reference Heinisch2003; Howard Reference Howard2000), and the populists’ desire to govern might overcome their distaste for the career bureaucracy (Peters and Pierre Reference Peters and Pierre2019). Also, populist parties may not make the best use of their most vocal and visible politicians if they are in the executive branch of government. Experts in populist political communication can be more useful for a populist party in the parliament. There, politicians are more free from the constraints placed on government ministers and junior ministers by coalition partners and by the prime minister. From the normality perspective, we would therefore expect populists to govern like politicians from any other party. Although some scholars have focused on ideological changes in – and intraparty developments of – populist parties that enter government, few, if any, systematic investigations of the inclusion–normalization perspective exist (Muis and Immerzeel Reference Muis and Immerzeel2017: 919; Tepe Reference Tepe and Thompson2019).

A contrasting perspective is that populists remain exceptional even in government. For a party with a tradition of anti-system opposition, there is a strong incentive to continue the opposition role while in government in order to reassure its core voters that the party has not sold out to the establishment (Elias and Tronconi Reference Elias and Tronconi2011: 508). Below, we develop concrete expectations from the continued exceptionalism perspective in relation to governance capability, cabinet decision making, political–administrative relationships and what we call communicative concerns.

Governance capability

According to Peters and Pierre (Reference Peters and Pierre2019), populist parties lack the capability to convert big ideas and popular slogans into public policies and to consider the minutiae of policy implementation. Populist parties are often relatively new and centralized and therefore have weak local party branches compared with those of established mass parties. This weakness reduces their ability to identify, recruit and develop political talents; they have relatively shallow pools to draw candidates from, once they enter the government. Moreover, protest and niche parties rarely have roots in vocational organizations, professional groups, educational institutions, regional associations or other milieux associated with governance capabilities. In patronage systems, limited access to governance expertise can mean that populist parties lack candidates to fill political appointee posts in the bureaucracy. In stricter merit systems, with political appointments being limited to executive politicians at the apex of government ministries, we can expect populist parties to appoint executive politicians who have less professional and political experience than those from large mainstream parties have.

On the other hand, populist parties ‘will need to ensure that the members of their government team (and their support staff) are competent’ if they want to have any chance of ‘achiev[ing] the party's strategic goals’ (Luther Reference Luther2011: 454–455). Upon being included for the first time in the national executive government, populist parties can thus be incentivized to place their most experienced representatives in the government: ones, for example, with experience from advanced positions in the legislature or from executive government at lower levels of government. Popular favourites can, as mentioned above, be more useful to the party in positions other than in the executive government.

In the normality perspective, that is, if ‘normality’ is the most accurate description of how populist parties tackle governing, we expect the same expertise among all parties in the cabinet. In the exceptionalism perspective, we expect less expertise among populist parties in the cabinet.

Cabinet decision making

According to Stoker (Reference Stoker2019: 14), ‘populism does not respect … core features of politics – the search for compromise between different interests [and] the need to understand another's position’. The art of reaching lasting compromises is of essential importance in multiparty governments, where different views exist between both policy sectors and political parties. Often, cabinet decisions cannot be reached by choosing either policy option A or B; one must instead find a compromise that contains some of policy A and some of policy B, after a period of sounding out – that is, consultations and negotiations that give several interested parties some influence over the final decision (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1983). In a cabinet, negotiations can be held and decisions reached in both informal consultations and formal arenas like cabinet meetings. Establishing effective mechanisms of intra-coalition decision making may prove crucial to solve conflicts in cabinets including populists (Luther Reference Luther2011: 454–455). As Kurt Richard Luther emphasizes, however, ‘the legacy of their anti-establishment rhetoric may make for strained relations, at least initially’, and since populists lack government experience they are ‘likely to be at a disadvantage vis-à-vis their coalition partners’ (Luther Reference Luther2011: 454–455). According to Stoker, populists lack the willingness and ability to search for compromise through ‘[g]overnance processes [that] are complex and tedious’ (Stoker Reference Stoker2019: 14).

In the normality perspective, we expect a similar emphasis amongst all parties on collegial bodies in the cabinet. In the exceptionalism perspective, we would expect that populists would put less emphasis on collegial bodies in the cabinet.

Political–administrative relationships

At the heart of the populist ideology lies the idea of the elite and the establishment as the antagonists to the virtuous people (Mudde Reference Mudde2004). For populists, civil servants are part of the elite, and many populist parties that enter government offices have a history of expressing highly sceptical views about the permanent civil service – a group with whom they must work closely while in government (Aucoin Reference Aucoin2012; Hart and Wille Reference Hart and Wille2006). The civil servants are seen as servants of the corrupt system and must therefore be sidelined and isolated as much as possible (Peters and Pierre Reference Peters and Pierre2019), thus detaching executive politicians from the bureaucracy (Drápalová and Wegrich Reference Drápalová and Wegrich2020). Also, political–administrative relationships are expected to become inherently distrustful, for example, with politicians having relatively little confidence in civil servants’ willingness and ability to give populist leaders what they need in terms of supporting evidence, arguments, and politically responsive advice (Eichbaum and Shaw Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2010).

In the normality perspective, we expect the same level of trust and contact between all politicians and the civil service. In the exceptionalism perspective, we would expect less trust and less contact between populists in the cabinet and the permanent civil service.

Communicative concerns

A strategy preferred by populist parties in government has been referred to as ‘one foot in, one foot out’; they have to influence policy on their core issues while maintaining their ‘outsider identity’ through ‘attention-grabbing statements’ and ‘spectacular actions’ (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2010: 1319–1329). By ‘continuing to voice concerns of disaffected voters from a position of public office’, populist parties in government may ‘continue to evoke political discontent among their supporters’ (Haugsgjerd Reference Haugsgjerd2019). This split strategy has been studied by looking at the external communication of populist parties (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2010). Participation in coalition cabinets involves making compromises, resulting in watered-down policies that can be difficult to sell to core voters. If they fear painful cabinet compromises and dissatisfied voters, populists in government will be more concerned about how their party is portrayed in the media and will care less about how the cabinet is described. As discussed above, populists are highly critical of the establishment, including the civil service. Populists will therefore be less concerned about how government apparatuses such as the ministry, subordinate agencies and the policy sector appear in the press.

In the normality perspective, we expect the same communicative concerns among populist and non-populist politicians. In the exceptionalism perspective, we expect populists to be more concerned about their party and less concerned about the civil service than the non-populists are.

Research setting

The Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) was established in 1973 (as Anders Lange's Party for Strong Reduction of Taxes, renamed the Progress Party in 1977) and obtained parliamentary representation the same year. Most scholars consider it a right-wing populist party and distinguish it from far-right populist parties (Bjerkem Reference Bjerkem2016; Jungar and Jupskås Reference Jungar and Jupskås2014; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019). According to other typologies, the Progress Party also fits the complete populism category (Jupskås et al. Reference Jupskås, Ivarsflaten, Kalsnes, Aalberg, Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and de Vreese2016). Historically, the Progress Party built its electoral success on tax cuts, strict law and order, and anti-immigration policies. Over time, however, the party has developed a broad political profile and built a professional party organization. On immigration policies, the Progress Party has nurtured a respectable image and demonstrated a stronger commitment to liberal rights than have far-right populist parties in other countries (Akkerman and Hagelund Reference Akkerman and Hagelund2007: 200). Unlike the Front National in France and other right-wing populist parties, the Progress Party has stayed true to its conservative economic policies; the party has not, for example, advocated for higher tariffs and other limits to free trade (Jupskås Reference Jupskås, Kriesi and Pappas2015; Otjes et al. Reference Otjes, Ivaldi, Jupskås and Mazzoleni2018).

Due to the party's anti-establishment positions and long history of criticizing the civil service, including immediately before the accession of the Solberg government in 2013, political commentators called the Progress Party's introduction into government ‘the acid test for the civil service’ (Salvesen Reference Salvesen2013). After more than six years, the Progress Party left the Solberg government in January 2020. While in government, the Progress Party controlled the Ministry of Justice (highly relevant for the party's law-and-order and anti-immigration profiles), the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs and the Ministry of Children and Equality.

Norway is a parliamentary democracy with a multiparty system, consisting of well-functioning membership parties and frequent coalition cabinets (Allern et al. Reference Allern, Heidar and Karlsen2016). The central administration comprises 15 ministries and the Prime Minister's Office. Each ministry has four to six expert departments staffed by tenured civil servants. Since the late 1940s the ministries have had two types of executive politician positions in addition to the minister position: the political adviser position and the state secretary position. State secretaries are mentioned in the Constitution. They are not part of the cabinet but serve as ministers’ stand-ins and are generally important actors in executive government. Political advisers are formally appointed by the Prime Minister's Office and should be at the personal disposal of the minister; they tend to be relatively young and have limited or no executive powers (Askim et al. Reference Askim, Karlsen and Kolltveit2017, Reference Askim, Karlsen and Kolltveit2018). Since 2000, each ministry typically has had one political adviser and two state secretaries. We call both ministerial advisers (MAs).

Norwegian cabinets have long collegial traditions that include a great willingness to compromise. Cabinet decisions are formally made either within individual ministries or in the Council of State. In reality, however, the weekly cabinet meetings are the main arena for clarifying and settling disagreements between ministries or parties (Kolltveit Reference Kolltveit2013).

Data and methods

We draw on data from the three most recent Norwegian cabinets covering a 20-year period, 2001–20. More precisely, we rely on survey data of former MAs (state secretaries and political advisers) from three Norwegian cabinets. We compare the data obtained from executive politicians from the populist Progress Party with the data obtained from MAs from six other political parties: the Solberg government (2013–today) consisted of the Conservative Party (2013–), the Progress Party (2013–20), the Liberal Party (2018–) and the Christian Democratic Party (2019–). The Stoltenberg II government (2005–13) consisted of the Labour Party, the Socialist Left Party and the Centre Party. The Bondevik II government (2001–5) consisted of the Conservative Party, the Christian Democratic Party and the Liberal Party.

The initial list of respondents was drawn from the Political System Directory of the Norwegian Social Science Data Services. Email addresses were collected from the websites of respondents’ current employers or provided by the national secretariat of their political party. We used Questback to distribute the surveys and to collect the data. The field periods were 2015 for Bondevik II and Stoltenberg II, and 2018 and 2020 for the Solberg government. The response rate was higher among MAs in the Stoltenberg II cabinet (76%, n = 145) than in the Bondevik II cabinet (65%, n = 60) and the Solberg cabinet (54%, n = 77). No other indications of analytically important bias were found in the sample. The frequency of non-responses to individual questions was negligible. All respondents received the survey after they had left government. The duration between their leaving government and their answering the survey varied, though; the time lag was longest for respondents from the Bondevik II government and shortest for respondents from the Solberg government. All three legs of the survey contained questions about the MAs’ activities in government, such as the types of advice offered to ministers, the types of assignment, the levels of responsibility and whether respondents could make independent decisions in the ministry. We cannot exclude the possibility of self-aggrandizement but have no reason to expect that it would vary systematically across parties or cabinets.

We operationalize governance capabilities as the experience of the MAs. The background and expertise of these MAs are measured through survey items asking about positions held before entering government. We compute an additive index counting the number of relevant positions held before appointment, both inside and outside politics (see Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

We operationalize cabinet decision making through four survey items asking about the importance of different strategies for cabinet decision making. ‘Thinking of issues that were solved at cabinet level, how important were the following arenas to reach an agreement?’ (scale from 1, not important at all, to 5, very important). Alternatives were: cabinet meetings, cabinet committees, bilateral talks with the prime minister, bilateral talks between ministers. We compute two mean indexes, one measuring the importance of collegial arenas and one measuring the importance of bilateral decision making.

We operationalize political–administrative relationships using survey items covering MAs’ opinions about the competence of the civil service and items covering MAs’ contact patterns. We measure opinions about the competence of the civil service with two items: ‘The civil service was able to take necessary political considerations into account in their professional recommendations’ and ‘Written material from the civil service provided a solid basis for political decisions’. We compute an index based on these two items (see Table 1). We measure contact patterns with several items based on the questions: ‘How often did you have direct contact with the following actors? Seldom/never, a few times a year, monthly, weekly or daily?’ We compute two indexes from these questions, one measuring political contact and one measuring contact with the bureaucracy (see Table 1).

We operationalize communicative concerns using survey items about how important it was for the respondents that various actors and organizations ‘appear in a good light in news stories about the ministry's policy area’. We compute two indexes based on these items, one measures political communicative concerns and the other bureaucratic communicative concerns (see Table 1).

Empirical analysis

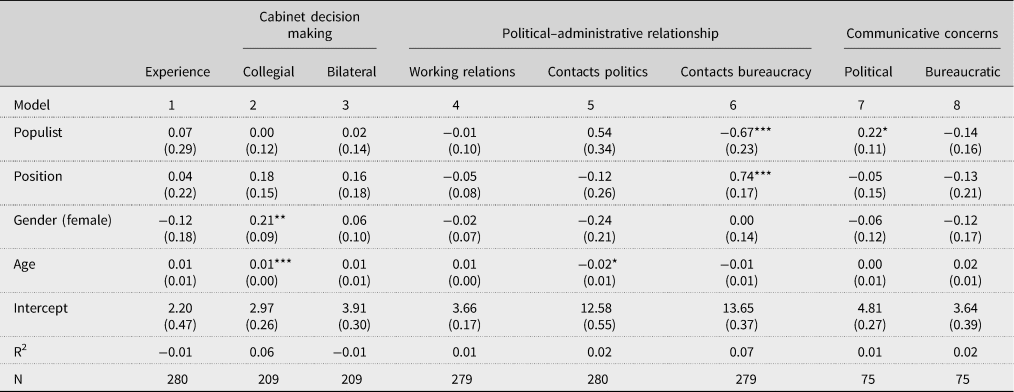

The empirical analysis is structured based on the analytical framework developed above. In Table 2 we investigate all four dimensions of that framework and report eight OLS analyses showing the overall picture of Progress Party MAs compared with MAs from other parties in the surveyed cabinets. We will comment on each dimension in turn, and when commenting we also include more detailed data analyses to give a more comprehensive picture of differences and similarities between populists and non-populists.

Table 2. Populist and Non-Populist MAs (OLS regression, B-coefficients)

Notes: Std dev. in parentheses. * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Governance capability

Model 1 in Table 2 showed that there was a significant difference in the work experience of populist and non-populist MAs. In Table 3 we scrutinize the work experience of the MAs.

Table 3. Professional Positions Held Before Being an MA (%)

Note: Answers not limited to the last position held before being MA. Many MAs had more than one position before being MA, so percentages sum to more than 100 per column.

Prior to entering their government positions, MAs from the Progress Party had elected positions as members of parliament, mayors and local politicians to a slightly greater extent than MAs from non-populist parties. However, Progress Party MAs had salaried non-elected (hired) positions in their political parties to a lesser extent than MAs from non-populist parties. The political experience of MAs is thus similar across the parties in the three cabinets, but Progress Party MAs tend to have comparatively more experience from elected political positions and comparatively less experience from salaried non-elected positions.

Progress Party MAs have considerable experience from leadership/management positions, on a par with non-populists in the Solberg cabinet and notably more so than MAs from the Stoltenberg and Bondevik cabinets have. It is particularly in management experience from the private sector that these populist MAs stand out. Finally, there are relatively only small differences between the populist and non-populist MAs when it comes to work experience from public relations, political communication and management consultancy. But again, populist MAs have more, rather than less, such experience than do non-populists.

Concerning formal education – a variable not included in the regression analysis – the survey data show that Norwegian MAs in general have high levels of formal education. However, fewer populist than non-populist MAs have completed a higher education degree. Seventy-three per cent of populist MAs had a master's degree, compared with 96% of non-populist MAs in the Solberg cabinet. In the Stoltenberg cabinet, 87% had a master's degree, and in the Bondevik cabinet, 97%.

Overall, despite being a newcomer to government, the Progress Party's history of governing at the local level evidently gives them a large pool of potential candidates for service at the national level. Similar observations have been made about populist parties in several other European countries as well (Drápalová and Wegrich Reference Drápalová and Wegrich2020). The results also confirm findings in existing research that show that Norwegian MAs are comparatively well educated and experienced (Askim et al. Reference Askim, Karlsen and Kolltveit2020).

Cabinet decision making

Models 2 and 3 in Table 2 show no significant differences between populist and non-populist MAs when it comes to seeing collegial or bilateral decision making in the cabinet as important. Table 4, which gives a more detailed picture, also shows that populist MAs generally view decision-making processes in the same way as non-populists do. What stands out is rather that the prime ministers’ different ways of organizing decision-making processes in the cabinet are reflected in the answers. It is evident, for example, that prime ministers Stoltenberg and Bondevik used cabinet committees more actively than Prime Minister Solberg did. When compared with their colleagues from other parties in the Solberg government, populist MAs place somewhat greater weight on cabinet committees, but other than that difference, MAs across parties in the Solberg cabinet are in agreement about the importance of the arenas for reaching agreement in the cabinet. Moreover, the standard deviation scores indicate that populist MAs are more, rather than less, consistent in their opinions than are non-populist MAs.

Table 4. The Importance of Decision Arenas to Reaching Agreement in the Cabinet (%)

Note: Survey question: ‘Thinking of issues that were solved at cabinet level, how important were the following arenas to reaching an agreement?’ Five-point scale (1 = not important at all; 2 = less important; 3 = neither/nor; 4 = quite important; 5 = very important).

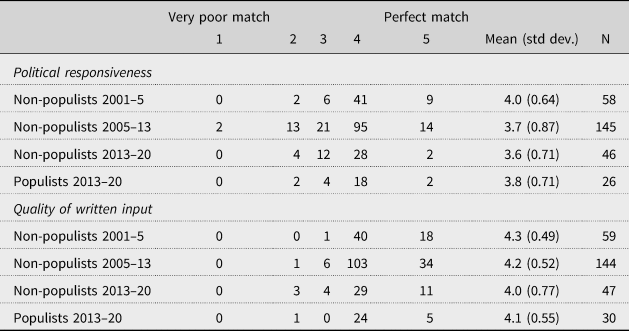

Political–administrative relationships

In Model 4 in Table 2, we saw no difference between populist MAs and others regarding political–administrative relationships. Table 5 shows in greater detail that MAs from all three cabinets agree that civil servants considered political matters when giving policy advice to the political leadership. Populist and non-populist MAs have the same views about such functional politicization. Likewise, populists and non-populists have the same views about the adequacy of the written input political leaders could obtain from civil servants. Non-populist MAs from the Bondevik government in the early 2000s expressed the most positive opinion on civil servants’ written input, but the differences are not noteworthy. The takeaway is that MAs from all three governments, populists included, expressed a positive opinion on their working relationships with civil servants.

Table 5. Political–Administrative Working Relations (%)

Note: Survey question: ‘How well do the following statements match your own experience from the political leadership in the ministry?’ Five-point Likert scale from 1: very poor match to 5: perfect match.

Models 5 and 6 in Table 2 show that populist MAs have less contact with the bureaucracy and to some extent more contact with party actors in parliament and in the party organization. Table 6 shows the proportion of MAs that had been in daily contact with various actors inside and outside the ministry. Here we see clear differences, not so much between governments as between populist and non-populist MAs. Compared with other MAs, populist MAs had less frequent contact with leaders and caseworkers in the civil service and more frequent contact with their own political party, particularly their party leadership and the party group in parliament.

Table 6. MAs with Daily Contact with Political and Bureaucratic Actors (%)

Note: Survey question: ‘How often did you have direct contact with the following actors? Seldom/never, a few times a year, monthly, weekly or daily?’

If we compare state secretaries only, and disregard political advisers, the differences between the populists and non-populists in the Solberg government increase. This increase is particularly evident in contacts with civil servants. For example, 74% of state secretaries from other parties in the Solberg government had been in daily contact with caseworkers compared with only 42% of state secretaries from the populist Progress Party.

Communicative concerns

Models 7 and 8 in Table 2 indicate that populist MAs are somewhat more concerned than other MAs are about how their own political party is portrayed in the media, while the two groups have similar concerns about how the government bureaucracy is portrayed. In Table 7, we investigate these relationships in more detail. Here we see that even though most populist MAs are similar to non-populist MAs, there are differences worth emphasizing. A few populists do not care about the cabinet's being framed positively in the media, and they also tend to care less about their policy area. However, almost all populists agree that it is very important that the minister (80%) and particularly the party (90%) appear in a good light in the media. Hence, although differences are small, the more detailed analysis shows there is a tendency for populist MAs to be more concerned about the party and less concerned about the bureaucracy than other MAs are.

Table 7. Communicative Concerns of MAs (%)

Note: Survey question: ‘Regarding media stories that deal with your organization's policy areas, how important do you think it is that [the actors/institutions in first column] appear in a good light?’ Five-point scale (1 = not important at all; 2 = less important; 3 = neither/nor; 4 = quite important; 5 = very important).

Discussion

Unlike most research on populist politics, ours has not focused on electoral gains and losses, ideological changes or intra-party developments. We contribute instead to a so-far thinner stream of research, one focused on consequences for government of including populist parties. If the normality pattern dominates, the machinery of executive government will be unaffected by the entry of populists – in terms of the functioning of the machinery of government. (To be sure, normality does not mean public policy is not affected by populist inclusion; public policy is outside the scope of this article.) In an exceptionalism scenario, populist parties crash government with, for example, low-calibre personnel, distrust in the permanent bureaucracy, a disregard for cross-party compromises and little concern about how the government and the bureaucracy are perceived by the outside world, as long as the party's electoral support grows. At stake are therefore important aspects of governance and public administration (Stoker Reference Stoker2019). In the Norwegian context, given the results summarized above, normality is a more accurate description than exceptionalism to describe what occurred when a populist party entered government for the first time.

Empirically, we used survey data from 282 ministerial advisers from one populist political party and six non-populist political parties and three government cabinets in Norway. Material from inside executive politics is clearly of great value to research. Still, a potential downside of relying on insider material is that politicians, when asked about their own roles, can portray themselves in a positive light or be secretive, and that populists may want to appear house-trained. We reduced vulnerability to such pitfalls by ensuring anonymity for the respondents, by collecting the data after respondents had left office and by giving respondents no clues to suspect that the exceptionalism of populists was a topic of interest. Surveying cabinet ministers rather than the junior executive politicians could also, potentially, yield different results. Cabinet ministers are, however, a group from whom it is notoriously difficult to obtain data.

Furthermore, the study is limited to selected phenomena that could be affected by the inclusion of populists in government. That the results vary across these selected phenomena suggests that conclusions one can draw from a study such as this are vulnerable to the choice of outcome variables. Achieving robust knowledge about the normality and exceptionalism associated with populists attaining power requires studies covering more variables and other empirical contexts.

Also, we cannot on current evidence distinguish clearly between normalization and just plain normal. The former refers to governing changing people and parties; the latter refers to populists having had their rough edges worn off by prior experience – for example, from parliamentary politics and governing at the subnational level – and to populism simply being unrelated to governing. Without additional data such as interviews with politicians and top civil servants, the two explanations for populists governing ‘normally’ cannot be distinguished. On outcome variables like the ones used in this study, the behavioural expectations of the two explanations are largely the same. Future research into the causes of ‘normality’ is therefore encouraged.

Moreover, if we assume ‘normalization’ explains ‘normal’ behaviour, any traits developed while in office might wane. Future research should therefore strive to investigate the processes of normalization and exceptionalism in a longitudinal perspective to investigate the durability of normalizing effects of government inclusion. If normalization washes off, populist parties will return to government with refreshed exceptionalism after a period of self-rediscovery in opposition – their hitherto natural habitat. Alternatively, normalization is more permanent, either by choice, based on the expectation that shedding populist ways brings a ‘respectability bonus’ (McDonnell and Werner Reference McDonnell and Werner2018: 760), by habit, in that being in government was a formative experience for a cohort of leading party representatives, or by personal ambition, in that the same cohort suddenly find life in opposition boring and want to find a way back into the government offices. Also, as observed by David Art, being in power can be a comprehensive and exclusive training course that upgrades the party's representatives’ human capital, vets candidates for future executive duty and professionalizes the party organization (Art Reference Art2011: 58).

Moreover, a party, not only its senior political figures, can switch from voter seeking to office seeking. We can speculate that the dynamics of possible reversion to exceptionalism are contingent upon, for example, the political profile of the government, with greater political distance between the government and the populist party shortening the half-life of normalization. Also, normalization likely washes off more quickly if the populist party experiences increased competition for votes from other populist parties, including single-issue parties.

The reverting-to-exceptionalism dynamics are likely also contingent on time. Any normalization should occur first and foremost among the party's leading representatives, that is, the individuals who experienced the inside of the machine of executive government, and it will take time for normalization to trickle down through the party. Therefore, if the party is only briefly in government, the party base will come out the other side relatively unaffected. Relatedly, if the populist party next spends a long period in opposition, the more the natural turnover of leading personnel will have peeled off the most ‘normalized’ layer of personnel, thus exposing the fresh wood of candidates with their populist exceptionalism intact.

By investigating how a populist party behaves when in government for the first time, we contribute to scholarship on the growing influence and the new roles of populist parties in democratic societies (e.g. Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017). One interpretation of our results is that achieving government inclusion – that is, crossing the final threshold a political movement or party must cross to become an integrated part of the political system – grinds populists’ hard edges down and turns populist parties into mainstream parties (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016; Allern Reference Allern2013).

Note, however, that our research design is double-edged. Surveying senior populist political figures who have recently quit government does bring a ‘fresh insider perspective’ advantage which is rarely seen in the literature. However, this data-collection strategy also comes with the risk of overestimating the normality of the party at large. As discussed just above, these senior figures and their insider entourages probably represent the most likely layer of the party in which to find ‘normality’, possibly individuals prepared and willing to fit in from the start. Scholarship on populist political parties has obviously gone beyond this layer to cover also the grassroots activists, who in the short term may be unaffected by any transformation among the party's senior political figures.

Moreover, we have not covered the behaviour of the party leadership. Some populist leaders are expert political communicators who have the ability to maintain a populist profile irrespective of what the party actually does in government, thus maintaining the support of the grassroots and the electorate. In short, insights about governance are not necessarily generalizable to other dimensions of ‘populists in power’, just as insights about, for example, the outward appearance of party leaders does not necessarily tell us the whole story of how the populist party actually handles executive power.

Populist parties differ across and also within countries, and that brings us to another note of caution related to generalization. Our results are to some extent shaped by our focus on a single populist party, Norway's Progress Party. Although new to governing at the national level, and ‘populist’ per established categorizations, the Progress Party has characteristics many will not associate with the notion of a populist party: almost 50 years of continuous parliamentary representation, substantial experience from governing at the subnational level and a party organization moulded on the mass-party model. Generalizing to political parties in other contexts – for example, parties with limited parliamentary experience – should therefore be done with great caution. Other populists could behave differently if included in government, and any normalizing effect of governing might be weaker than in the present context.

More research is needed, ideally comparative studies with several populist parties, to get a fuller understanding of why populist parties behave in a certain way in executive government. This goes back to the normalized or just ‘normal’ distinction. Populist parties might generally be less exceptional than many think, at least as far as governance is concerned – that is, the sometimes mundane work that goes on at a level beneath the boisterous populist rhetoric. Also, it might be useful to explore in future research whether there are different types of populist political parties, differentiated, for example, by the level of professionalism, moderation and concern about their wider reputation. Norway's Progress Party is in many ways comparable to populist right-wing parties in Denmark and Sweden – parties that for the past 20 years have chosen to be in faction with relatively mainstream conservative parties in the European Parliament rather than with Austria's Freedom Party and other more far-right populist parties (McDonnell and Werner Reference McDonnell and Werner2018). By implication, it might not have taken much transformation for a party such as Norway's Progress Party to become ‘normalized’. However, following this line of thought, one could consider the Progress Party a critical test for the notion of exceptionalism: that we do find elements of exceptionalism, even here, suggests that such elements should be more likely in other contexts when other more extreme populist parties come to power. Again, only future empirical studies can help identify the importance of party characteristics, also of ones at levels below possibly too crude characteristics like ‘populist’.

Conclusion

In this article, we asked if and how government is affected by including populists; the answer, given the Norwegian experience, is mixed. We found that, compared with non-populist parties, the populists appointed personnel with ample professional experience to office, adhered to collegial decision making and thought the bureaucracy delivered quality and were politically responsive. Populist executive politicians remained somewhat exceptional, though, in that they had more frequent contacts with party heavyweights and less frequent contacts with top bureaucrats than non-populist colleagues had. Populists were concerned about the media coverage of the coalition government and of the bureaucracy. However, compared with non-populist colleagues, populists were relatively more concerned for their own party and relatively less concerned for the government and the bureaucracy.

The results from this study accentuate the importance of investigating the consequences of populist inclusion in government along not one, but several dimensions. While populist executive politicians can be similar to other executive politicians along some dimensions, on others they can differ to a greater extent. We have shown that populists, when in power, think and behave much as other executive politicians from traditional political parties do, but we have also shown that as a group they remain somewhat different, if not exceptional.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for comments from three anonymous reviewers for Government and Opposition, Dag Ingvar Jacobsen and participants at the panel on ‘Democracy and Bureaucracy’ during the ECPR General Conference, 24–28 August 2020. The study received funding from the Research Council of Norway (grant number 258956).