No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

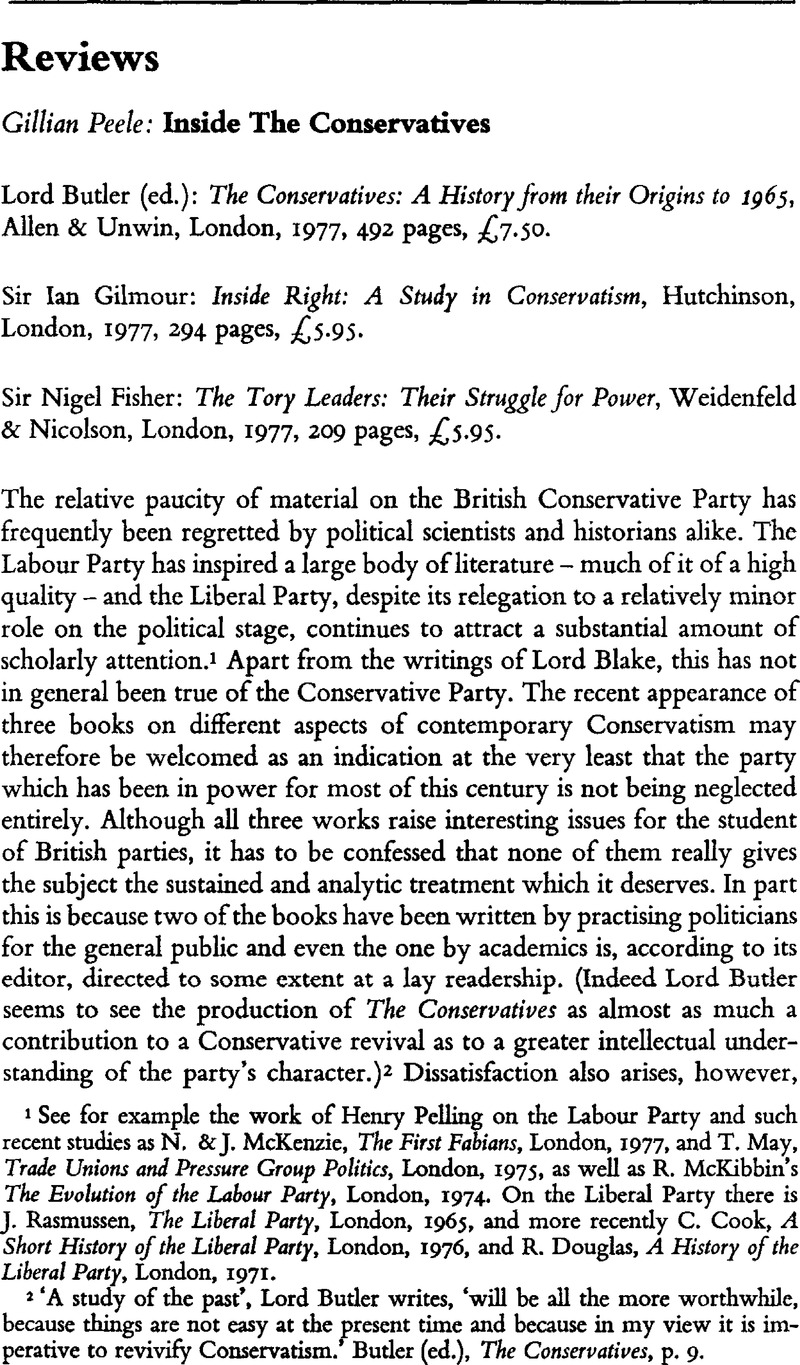

Inside The Conservatives - Lord Butler (ed.): The Conservatives: A History from their Origins to 1965 Allen & Unwin, London, 1977, 492 pages, £7.50. - Sir Ian Gilmour: Inside Right: A Study in Conservatism Hutchinson, London, 1977, 294 pages, £5.95. - Sir Nigel Fisher: The Tory Leaders: Their Struggle for Power Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1977, 209 pages, £5.95.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Government and Opposition Ltd 1978

References

1 See for example the work of Henry Pelling on the Labour Party and such recent studies as N. & J. McKenzie, The First Fabians, London, 1977, and T. May, Trade Unions and Pressure Group Politics, London, 1975, as well as R. McKibbin’s The Evolution of the Labour Party, London, 1974. On the Liberal Party there is J. Rasmussen, The Liberal Party, London, 1965, and more recently C. Cook, A Short History of the Liberal Party, London, 1976, and R. Douglas, A History of the Liberal Party, London, 1971.

2 ‘A study of the past’ , Lord Butler writes, ‘will be all the more worthwhile, because things are not easy at the present time and because in my view it is imperative to revivify Conservatism.’ Butler (ed.), The Conservatives, p. 9.

3 Very little use is made for example of the work of D. Butler and D. Stokes, Political Change in Britain, London, 1969, although Dr Ramsden does use material from the Nuffield General Flection Series.

4 The phrase ‘ catch-all party’ is generally associated with O. Kircheimer. See his essay in J. La Pdombara and M. Weiner (eds.), Political Parties and Political Development-Princeton, 1966. The best recent work on the analysis of political parties is G. Sartori, Parties and Party Systems, Cambridge, 1976.

5 See for example Patrick Seyd’s stimulating article on the role of the Monday Club in the Conservative Party in Government and Opposition, vol. 7, no. 4, 1972, where he argues that the formation and growth of the Club could be a ‘further sign’ of the changing nature of the Conservative Party.

6 Quoted in Fisher, The Tory Leaders, p. 155.

7 It is clear that the main beneficiary of the Houghton Committee’ s proposals will be the Labour Party and that the system of public subsidies there envisaged will, if implemented, transform all British parties into publicly accountable organizations. See Report of the Committee on Financial Aid to Political Parties. Cmd 6601, London, HMSO, 1976. It will probably not be implemented unless Labour wins the next election.

8 The thesis that internal developments in the majority party are soon reflected in minority parties has, of course, been put forward in relation specifically to American politics. See Samuel Lubell, The Future of American Politics, 2nd ed., New York, 1955. Also the comments by Everett Ladd, American Political Parties: Social Changes and Political Response, New York, 1970, and R. L. Rubin, Party Dynamics, New York, 1976.

9 See Michael Oakeshott's essays collected in Rationalism in Politics, London, 1962.

10 Professor Gash quotes Burke’s Fourth Letter on a Regicide Peace as evidence for the proposition that Burke ultimately came close to accepting the name of Tory. “Scarce’ wrote Burke, ‘had the Gallick harbinger of peace and light began to utter his lively notes, than all the cackling of us poor Tory geese to alarm the garrison of the Capitol was forgot.’ Butler (ed.), op. cit., p. 107. Burke’s comment is perhaps as easily interpreted ironically.

11 Ibid., pp. 76-77.

12 Ibid., pp. 76-77.

13 Dr Southgate does mention R. McKenzie and A. Silver’s, Angels in Marble, London, 1968, as being of ‘some interest’ but he does not develop the point. For a usefd review of some of the literature on working-class Conservatism see F. Parkin, Class Inequality and Political Order, London, 1972, and Bob Jessup, Traditionalism. Conservatism and British Political Culture, Cambridge, 1974.

14 See Parkin’s works for a persuasive statement of the view that it is not so much working-class Conservatism that needs to be explained as Labour voting. See especially ‘Working Class Conservatives’ in British Journal of Sociofogy, 1967, vol. XVIII, pp. 278-90.

15 Butler, (ed.), op. cit., p. 415.

16 Ibid., p. 420.

17 See the division lists reprinted in The Times, 16 December, 1977.

18 Gilmour, Inside Right, p. 167.

19 H. M. Drucker, The Political Uses of Ideology, London, 1974. For a rather different perspective on Conservative ideology see Robert Eccleshall, ‘English Conservatism as Ideology’ in Political Studies, vol. XXV, No. I, 1977. Eccleshall characterizes Conservatism as an ideology of dominant social and political groups and concludes these groups are likely to succeed 'in making practical adjustments to changing economic realities’. He sees the future of Conservatism as possibly containing a blend of ‘Mallock style defence of entrepreneurship’ with a form of populism.

20 Viscount Hailsham’s The Case for Conservatism was originally published in 1947. It was revised and published as The Conservative Case in 1959. H. M. Drucker makes the point that much of Oakeshott's political writing dates from the late 1940s-a period which he sees as especially significant for the development of intellectual opposition to ‘ ideology’. Drucker, op. cit., p. 118.

21 D. Butler and D. Stokes in the first edition of Political Change in Britain, 1969, discuss at some length the characteristics of the British electorate leading to a Labour advantage at the polls in the future. This is treated a little more sceptically in the second edition of 1974.

22 A. O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice and Loyalty, Cambridge, Mass., 1970. For the concept of adversary politics see S. E. Finer (ed.), Adversary Politics and Electoral Reform, London, 1975.

23 Fisher, op. cit., pp. 170-71 and the discussion in Appendix I.

24 Some discussion of candidate selection occurs in Lyndelle Fairlie ‘Candidate Selection Role Perceptions of Conservative and Labour Party Secretary/Agents‘, in Political Studies, vol. XXIV, No. 3, 1976.