Electoral quotas have become a popular tool for increasing the political presence of underrepresented groups. In new democracies, electoral engineering promises to legislate norms of inclusiveness and representative democracy (Dahlerup and Darhour Reference Dahlerup, Darhour, Dahlerup and Darhour2020). The extent to which this is achieved arguably depends on whether parties comply with the regulations and how they implement them (Bruhn Reference Bruhn2003; Kenny and Verge Reference Kenny and Verge2013). However, little is known about reasons for quota compliance varying: Why do some parties comply with quotas, while others do not?

This article addresses the above question by focusing on the case of Tunisia. The country is now considered one of the most democratic in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (V-Dem 2020), and the adoption of electoral quotas for several groups at different levels of government has been an integral part of the transition process (Belschner Reference Belschner2018; Gana Reference Gana2013). Tunisia's first local elections following the 2011 revolution were held in 2018. Four electoral quotas for women, youth and people with disabilities (PwD) regulated the composition of parties’ candidate lists. All quotas required comparatively high shares of candidates from underrepresented groups and were enforced by list rejection or deprivation of state funding in cases of non-compliance. The quotas were highly effective in securing group representation in Tunisian local councils: women, youth and PwD won 47%, 37% and 25% of council seats, respectively. However, these results were mainly driven by the ruling party, Ennahda. While this conservative Islamist party complied fully with all quotas on almost all of its lists, smaller secular and left-leaning parties lost up to 15% of their submitted lists due to non-fulfilment of the ‘horizontal’ gender parity quota and had to renounce around 50% of their campaign reimbursement for missing the PwD quota.Footnote 1 This is puzzling, considering that these parties submitted significantly fewer lists than Ennahda and given that previous literature found younger left-wing parties to be more willing to comply with quotas (Murray Reference Murray2007; Verge and Espírito-Santo Reference Verge and Espírito-Santo2016).

This article argues that parties must be not only willing to comply with quotas but also able to do so. It suggests that parties’ ability to comply with quotas is significantly constrained by their organizational strength – the number and territorial extension of their membership as well as their financial and human resources (Webb and Keith Reference Webb, Keith and Scarrow2017). The more numerous and complex the mandatory quotas, the more challenging implementation becomes for organizationally weak parties. This argument specifically applies to new democracies, where we tend to see greater variation in parties’ organizational strength than we do in established democracies.

In newly democratic contexts, parties with greater organizational strength – particularly current or former ruling parties (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2016a) – are usually better equipped to enact long-term electoral strategies that benefit the party as a whole. Specifically, organizationally strong parties profit from competitive advantages in candidate selection, candidate placement and the coordination of lists – that is, the processes through which quota implementation takes place.

The argument in this article is developed and substantiated based on an in-depth analysis of the 2018 Tunisian local elections. I first draw on electoral data to map quota compliance at the party level. I then suggest explanations for the emerging patterns, based on 25 in-depth interviews with candidates, policy experts and party selectors.

The article adds to the existing literature in three ways. First, it focuses on electoral engineering in the specific context of new democracies and, thereby, complements accounts of how parties deal with quotas in advanced democracies (Murray Reference Murray2004, Reference Murray2007; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2009) and electoral autocracies (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2016a; Bush and Gao Reference Bush and Gao2017; Muriaas and Wang Reference Muriaas and Wang2012). Second, it speaks to an emerging comparative literature on quotas and electoral engineering (Htun Reference Htun2004; Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2010). Analysing and comparing compliance strategies with quotas for women, youth and PwD, this study goes beyond the usual focus on gender. Third, the article contributes to the literature on Islamist parties in the MENA region, focusing on their electoral strategies rather than on ideological aspects (Wegner and Cavatorta Reference Wegner and Cavatorta2019).

The article also has potential policy implications. Islamist parties are often powerful, organizationally strong actors in MENA politics, and it is important to be aware of their competitive advantages when dealing with electoral quotas. While a narrow focus on ideology and willingness to support gender equality may suggest that such parties would be unwilling to comply with quotas, broadening the perspective to include parties’ capacities may change that impression. In general, the article sheds light on potential side effects of strong quota regulations in new democracies. Electoral engineering may enable stronger party organizations to submit more lists, win more seats and aggregate more resources than smaller opposition parties – and thus, in turn, have unintended side effects on party and party system consolidation.

Theory: parties’ compliance with electoral quotas

Electoral quotas come in a variety of types and designs, but all of them intend to increase the presence of underrepresented groups in politics. This article specifically focuses on legislated candidate quotas, which mandate shares and placement of candidates belonging to targeted groups on electoral lists.

The differing motives of parties and regimes in adopting electoral quotas have received substantial scholarly attention (Bush Reference Bush2011; Kang and Tripp Reference Kang and Tripp2018), and a successive body of literature has inquired about the reasons why parties’ compliance with such regulations may vary. Studies have shown, theoretically and empirically, that legislated candidate quotas are most effective in guaranteeing compliance when they include strong sanctioning mechanisms (Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2009). Finding that parties are more likely to implement quotas when sanctioned via the rejection of lists than when facing financial sanctions for non-compliance, scholars have concluded that parties’ willingness is a crucial mechanism for explaining (non)compliance (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes2019; Murray Reference Murray2007). Accordingly, several studies argue that younger and left-wing parties – which have less ‘sticky’ institutions and are ideologically more favourable to equality policies than older and conservative parties – are more likely to comply (Verge and Espírito-Santo Reference Verge and Espírito-Santo2016; Verge and Wiesehomeier Reference Verge and Wiesehomeier2019).

While such studies primarily focus on parties and quota implementation in established democracies, an emerging body of research has investigated parties’ compliance with quotas in electoral autocracies and hybrid regimes. Sarah Bush and Eleanor Gao (Reference Bush and Gao2017) argue that small conservative tribes in Jordan have a specific incentive to (over-)comply with gender quotas in that, by doing so, they will win more seats in total. Elin Bjarnegård and Pär Zetterberg (Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2016a) find that government parties in autocratic Tanzania are better placed than opposition parties to reconcile gender quota compliance with electoral strategies.

In new democracies, the electoral playing field should be less skewed than in autocratic systems, but dynamics may still differ considerably from those in established democracies. Indeed, in a cross-national study of parties’ compliance with electoral quotas in Latin America, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg (Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2016b) found that the bureaucratization of candidate selection procedures is the best predictor for parties’ compliance with legislated candidate quotas – as opposed to ideology, which appears insignificant.

The argument: party organizational strength and quota compliance

How, then, does the context of new democracies affect parties’ compliance with electoral quotas, and why does party ideology seem to be less important? Richard Matland and Donley Studlar argue that ‘to move in a specific direction in reaction to some external event requires … a willingness by the dominant coalition within the party to support a change, and the resources to implement the agreed-upon change’ (Matland and Studlar Reference Matland and Studlar1996: 712). Thus, compliance with new electoral rules will depend on both parties’ willingness and their capacities.

This article argues that the latter factor may be specifically relevant in new democracies, where electoral competition differs, structurally, from that found in established democracies. In general, party systems are still emerging and more fragmented (Randall Reference Randall, Katz and Crotty2006). Ellen Lust and David Waldner (Reference Lust, Waldner, Bermeo and Yashar2016) identify relic parties, movement parties and novice parties as the main types of parties competing in democratizing electoral systems. These types are differentiated based on their organizational strength – defined as the number and territorial spread of their membership – and their human and financial resources – that is, party staff and budget (Webb and Keith Reference Webb, Keith and Scarrow2017).

New democracies often feature a high number of weakly organized ‘novice’ parties, constructed around known personalities and generally lacking a broad membership base and human and financial resources (Randall and Svåsand Reference Randall and Svåsand2002). These compete with organizationally more powerful relic and movement parties. In the MENA region, most Islamist parties would fall into the latter category, translating wide and deep social support into political advantage (Lust and Waldner Reference Lust, Waldner, Bermeo and Yashar2016: 172). Depending on the specific context, they may be countered by so-called relic parties – successor organizations of former ruling parties. Thus, variation in the organizational strength of parties tends to be more pronounced in new democracies than in established democracies.

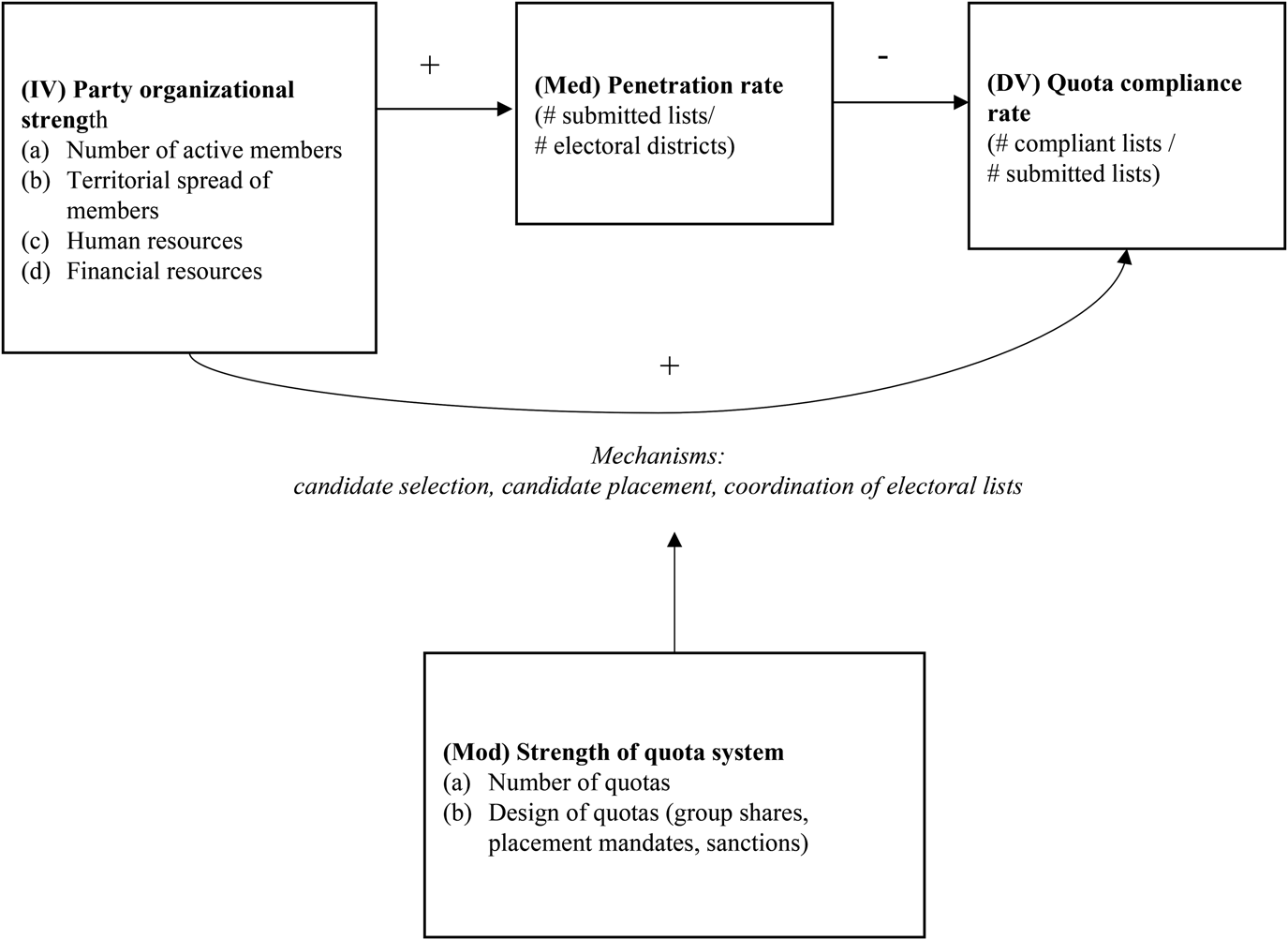

This article, based on the empirical evidence presented in the following sections, therefore suggests that, in the context of emerging democracies, party organizational strength positively influences quota compliance by conditioning parties’ strategic options in terms of candidate selection, candidate placement and the coordination of electoral lists. Specifically, I suggest that organizationally stronger parties with more members are able to identify more candidates belonging to groups targeted by the quota. Parties with greater financial resources may also be able to offer these candidates benefits for running. Furthermore, a greater territorial spread throughout the territory will allow organizationally strong parties to identify more relevant candidates throughout several electoral districts – that is, on a higher number of lists.

Second, organizationally stronger parties with more administrative staff and larger organizational structures on both the local and the national level will have advantages in controlling candidate placement on local lists as well as in coordinating local lists nationally. This is beneficial for quota compliance because (central) party organizations can thus make sure that quota-targeted candidates are placed on local lists according to the requirements (e.g. following a zipper principle or other placement rules). This is particularly important in cases where the interests of local lists (winning local seats) may conflict with those of the central party organization (e.g. securing long-term funding). Furthermore, quota designs like the Tunisian horizontal gender parity quota that put lists in an interdependent relationship to one another require the central control of all party lists at the national level. Parties with greater administrative bodies and more financial resources to invest in the electoral process may be able to decide centrally which lists will have to fulfil the quota, rather than leaving this decision up to each individual list.

I argue that the relationship between party organizational strength and quota compliance rate is mediated (Baron and Kenny Reference Baron and Kenny1986) by the penetration rate – that is, the ratio of submitted party lists to the number of electoral districts. Organizationally stronger parties could be expected to evince higher penetration rates – submit lists in a high share of all electoral districts. One could then expect a slightly negative relationship between the rates of penetration and quota compliance on the basis that it is more difficult for parties to ensure compliance if they submit many lists.

I then suggest the effect that party organizational strength has on quota compliance rates is moderated by the strength of the quota system. This means that the effect size should increase under stronger quota systems, defined by the number of quotas with which parties must comply in an election, as well as the type of quotas. Put differently, the impact of organizational strength on quota compliance should increase with the number of quotas in effect, the proportion of the requested groups’ shares and the strictness of placement mandates and sanctioning mechanisms. All identified mechanisms through which organizational strength impacts on quota compliance rate – candidate selection, candidate placement, and coordination of electoral lists – should thus be more difficult to complete (i.e. more dependent on party capacities) under strong quota systems. The effect of parties’ organizational strength on their quota compliance rates and how the quota system affects this relationship is the focus of this article and will be illustrated throughout the empirical analysis.

Figure 1 presents a schematic illustration of the suggested relationships between the investigated variables.Footnote 2

Figure 1. Theoretical Model

The context: quotas and parties in post-revolution Tunisia

Both the Tunisian party system and the rules under which elections take place changed considerably in the wake of the 2011 revolution. It took three years to devise a new electoral code for national elections (2014) and three more years to agree on one for elections at the local level (2017). The local elections were initially set to take place in 2016 but were postponed several times. They eventually took place in May 2018. Tunisia had previously been a highly centralized state, and the local electoral system was created from scratch. In 350 municipalities, under a proportional representation (PR) system with closed electoral lists, the Tunisian citizens now elect between 12 and 60 members to local councils (7,212 councillors in total).

One central point of discussion when creating the electoral system was the design of electoral quotas. Supported by a campaign of domestic women's activists, the quota system became even more ambitious than the equivalent system operating on the national level. Not only must all lists contain 50% female and male candidates in alternating order (‘vertical’ parity gender quota), but half of the lists per party must also be headed by a female candidate (‘horizontal’ parity quota). A youth quota requires all lists to include at least one candidate under 35 years of age in one of the first three positions, and then among every block of six candidates. These gender and youth quotas are enforced by the rejection of non-compliant lists. Finally, if a list includes one PwD among its first 10 candidates, the state will refund its expenses for the election campaign. This corresponds with a 100% financial penalty in case of non-compliance.

The Tunisian party system is typical for a transitional democracy. In general, parties were not prominent vehicles of political power during Ben Ali's authoritarian rule (Hamid Reference Hamid and Kamrawa2014: 132), meaning that, with the exception of the ruling Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD), parties had weakly developed structures and political opposition was carried out either in civic associations or in the prohibited Islamist movement (Resta Reference Resta, Cavatorta and Storm2018). While it is true that parties gained political relevance after the revolution (Storm Reference Storm and Szmolka2017), they did not do so equally.

First, the Islamist party Ennahda re-emerged on the political scene. Ennahda fits the movement party type: it generates wide and deep social support via its long-term focus on education and social service provision (Hamid Reference Hamid and Kamrawa2014: 131). It is also the most organizationally powerful player in the Tunisian party system: Ennahda is the only party with local branches all over Tunisia and has the highest number of members (interview IE2, ISIE). It also has access to considerable financial and human resources. The party's official budget in 2017 was 5.8 million dinars (about 2.4 million euros), and it employs a permanent staff of about 120 people (interview IS8, Ennahda, member of executive office).

Second, the RCD itself was banned in 2011. However, formal and informal networks surrounding the former powerholders resulted in the formation of the (nominally) secular party of Nidâa Tounès in 2012 (Wolf Reference Wolf, Cavatorta and Storm2018: 51). According to Aytuğ Şaşmaz et al. (Reference Şaşmaz2018), around 26% of the candidates running for Nidâa Tounès in the 2018 local elections were former RCD members. This party is, thus, a weak form of a relic party. Ideologically, it is largely secular but has a somewhat nationalistic orientation (Aydogan Reference Aydogan2020). Thanks to its connections with businesspeople and former powerholders, Nidâa is also a resource-rich party, although to a lesser degree than Ennahda. In 2013, the party declared a budget of 2.1 million dinars, which was less than half of Ennahda's budget in 2017. Its organization and institutional structures, particularly in rural areas, are less developed than Ennahda's and, with some exceptions, concentrated in the urban littoral areas of the country (interview IS10, Nidâa Tounès, member of executive office).

Third, a multitude of ‘novice parties’ have emerged in the years since the revolution. Many of these small, organizationally weak parties originated in civil society or formed around prominent political or business figures (Yerkes and Yahmed Reference Yerkes and Yahmed2019). They tend to be in constant processes of dissolution and re-formation. A recent report estimated the total number of parties registered in Tunisia at around 215 (Yerkes and Yahmed Reference Yerkes and Yahmed2019: 15). Ideologically, most of these parties can be considered secular, with some tending more towards a left-wing political agenda (e.g. the Front Populaire) and others taking a more liberal (e.g. Afek Tounès) or right-wing direction (e.g. Courant Démocrate). Common characteristics of these parties are that they are resource weak, have few offices outside Tunis and are often closely identified with the party founder or current leader (Yerkes and Yahmed Reference Yerkes and Yahmed2019: 14).Footnote 3

Unsurprisingly, this fragmented party system left Ennahda in a dominant position, participating in all elected governments since the revolution and collecting the highest share of votes in the most recent national elections in 2019.

In sum, Tunisia is a case that represents multiple regional trends in terms of both electoral engineering and parties and party systems. First, the trend in electoral engineering goes towards extending provisions for women to other underrepresented groups and to employing different quota systems at different levels of government. In the MENA region, 18 out of 19 states use gender quotas. A third of those have also adopted electoral quotas for other groups and half employ distinctive quota systems at different levels of government (International IDEA n.d.; IPU 2018; Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2010). Second, the Tunisian party system is typical of the region and of new democracies in general: The primary dimension of party competition is the religious–secular divide (Aydogan Reference Aydogan2020); Islamist parties are powerful (Hamid Reference Hamid and Kamrawa2014), and left-wing parties tend to be weak and fragmented (Resta Reference Resta, Cavatorta and Storm2018). The party system is volatile and composed of one or two dominant (government) parties and a multitude of weakly institutionalized opposition parties.

The 2018 local elections were the first after the revolution. In principle, this context presents some favourable conditions for fair party competition and quota compliance: The former ruling party was disbanded and not allowed to participate in the elections. Thus, while some parties had existed for longer, almost all had started organizing on the ground for elections around the same time (beginning of 2018), with Ennahda being the only party that recruited candidates as early as summer 2017.

Data and sources

This article relies on both quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative data are official election data collected by the central electoral authority (Instance Supérieure Indépendante pour les Elections – ISIE) and is mostly unpublished.Footnote 4 I obtained these data via email requests and in an interview with a representative from ISIE. To interpret and explain variation in compliance between parties and quotas shown in these data, I draw on 25 interviews that I conducted with candidates, policy experts and party/list selectors. The candidates and selectors represented six different parties (Ennahda, Nidâa Tounès, Afek Tounès, Beni Watani, Courant Démocrate and Front Populaire) as well as two independent lists. In total, I collected interviews in eight different municipalities, which varied in terms of their urbanity/rurality and party dominance.Footnote 5 Please refer to the Online Appendix for detailed information about data collection and analysis.

Patterns of quota compliance in the 2018 Tunisian local elections

Table 1 provides an overview of the main parties and formations competing in the Tunisian elections. The first column groups them into independent groups, parties and coalitions. A peculiarity of the Tunisian system is that only about half of all lists were presented by political parties; 42% of the lists were independent – that is, only ran in one specific municipality – and 8% were coalition lists. Different political parties jointly compile these lists and run them under the name of the coalition.

Table 1. Overview of Competing Parties and Groupings in Tunisian Municipal Elections

Notes: aNumber of lists submitted/number of municipalities. b1 – number of rejected lists/number of submitted lists. cNumber of compliant lists/number of submitted lists. *Only available as an aggregated figure (parties are differentiated by ISIE as Ennahda, Nidâa Tounès, others).

The second column displays the penetration rate per grouping. It is calculated as the ratio of submitted lists to the total number of municipalities (350). For example, there were, on average, 2.5 independent lists competing in each municipality. Ennahda had the highest penetration rate among parties, with exactly one Ennahda list in each Tunisian municipality. The parties that I have grouped under the heading of ‘small secular parties’ are all novice parties and, as described above, characterized by a lack of organizational strength. In contrast to Ennahda and Nidâa Tounès, their penetration rates are very low, meaning that they did not compete in the majority of Tunisian municipalities.

The remaining columns display variation by party across the different types of quotas. To interpret the figures, it is important to remember that each submitted list had to comply with three quotas in order to avoid rejection: vertical gender parity (VGP), the youth quota (YQ) and horizontal gender parity (HGP, 50% of lists per party headed by a female top candidate). The central electoral authority ISIE examined all submitted lists and rejected those that did not comply with any one of these quotas. While this was relatively straightforward in the case of VGP and the YQ, the procedure for HGP was more complicated due to the design of this quota. Logically, it only applies to parties and coalitions – that is, to groups running lists in more than one municipality. The ISIE would determine the total number of lists submitted by a specific party and, if fewer than 50% were headed by a female candidate, reject as many of the respective party's lists as necessary to achieve horizontal parity, counting backwards from the time of submission (interview IE2, ISIE). In most small parties, lists were not collectively submitted to the ISIE by the national party organization, but by the respective top candidates of the local lists. However, HGP was controlled on the national level. Thus, while central party leaderships advised their local lists to make sure that half of all lists per governorate were headed by female candidates, failing to meet this goal resulted in the rejection of the party lists (with male top candidates) submitted latest – regardless which governorate they came from.

As can be seen in columns two and five, nearly all submitted lists have complied with the vertical gender parity quota (VGP, alternate placement of male and female candidates): only seven lists in total were rejected. Also, nearly all lists equally complied with the youth quota. In total, 21 lists were rejected because of non-compliance with this quota. In both cases, non-compliance with these quotas was concentrated in independent lists and small parties.

The fourth column in Table 1 shows that the two big parties – Ennahda and Nidâa Tounès – managed a high rate of compliance with the requirement of horizontal parity. Independent lists were not subject to this quota as each only ran in one municipality. On average, only 3% of the top candidates from independent lists were female. In contrast, HGP was compulsory for the small secular parties, which had, on average, lower compliance rates than the two big parties. Those parties who submitted more lists – for example, Machrouu Tounès, Echâab and the Courant Démocrate – appear to have had the biggest problems complying with HGP. Others, like Afek Tounès and Beni Watani, submitted fewer lists and got no rejections. This seems logical, given that submitting more lists requires more effort in terms of central coordination to make sure that – when aggregated on the national level – HGP is met. The average compliance rates with the HGP quota were lowest for coalition formations. For instance, the Front Populaire had 20 of 132 submitted lists (15%) rejected due to non-compliance with horizontal parity.

Finally, as shown in the sixth column, there was most variation in the compliance rates between parties when it came to the PwD quota. The lower average level of compliance with this quota can be largely attributed to the sanctioning mechanism, which differs from that of the three other quotas. While failure to comply with VGP, the YQ or HGP led to the rejection of lists, lists that either did not have a candidate with disabilities or did not place him or her among the first 10 candidates ‘only’ had to renounce the reimbursement of their campaign expenditure.

When it comes to variation between parties’ (non-)compliance with the PwD quota, we see the same rank order of compliance as with HGP. Ennahda complied on 290 of 350 lists – on 83%. Nidâa Tounès and the small secular parties all had lower compliance rates.Footnote 6 Again, coalition lists perform worst, with only a quarter complying with the PwD quota.

Those patterns are puzzling in several regards. While quota compliance rates of 80–90% may seem reasonable, note that this variable only accounts for compliance on the lists that were actually submitted. This means that parties that already ran a low number of lists lost up to an additional 15% of those lists that they had compiled and submitted (and invested their limited time and money in) because they did not have gender balance among the top candidates. This is surprising, considering that most lists complied with VGP and that fulfilment of HGP would simply have involved changing the order of candidates before submitting the lists. Furthermore, the small parties are resource weak and would have particularly benefited from campaign reimbursement. Instead, and contrary to previous findings on quotas with financial sanctions (Achin et al. Reference Achin and Muriaas2020), the resource-rich Ennahda was the biggest complier. Finally, these patterns do not seem to relate to party ideology, where one would expect left-wing and secular parties to support equality policies and, thus, comply more readily than the centrist and Islamist parties.

Analysis: parties’ quota compliance strategies

To explain these patterns of (non-)compliance, the article draws on findings from the qualitative interviews. It suggests that there were three types of quota compliance strategies – minimal, partial and full compliance. My core argument here is that parties’ organizational strength limited the types of compliance strategies available to them – on both the central and the local level.

Minimal compliance: independent lists and coalitions

Groupings pursuing a minimal compliance strategy concentrated on the implementation of VGP and the YQ found ways to circumvent HGP and opted out of the PwD quota. Most independent and coalition lists followed this strategy.

The interview findings illustrate that selectors ranked the different quotas by the difficulty of compliance. The youth quota was considered easiest to comply with. Interviewees referred to the high proportion of youth among civil society activists and high youth unemployment (which, ironically, leads to youth being able to invest time in political activity) as positive factors for their recruitment on candidate lists. The great majority of all lists also complied with vertical gender parity – that is, the alternating placement of male and female candidates. So why did specifically coalition lists fail to implement horizontal parity?

The interviewees highlighted two challenges. The first is an electoral one: In general, many selectors considered it more difficult to get a list elected if it had a female top candidate, especially in rural areas and the south of Tunisia. This connects to a second challenge inherent in the design of HGP, which is the necessity of coordinating lists across different municipalities (Şaşmaz et al. Reference Şaşmaz2018). Consider this statement from a female candidate from the Front Populaire running on a coalition list. It illustrates the dilemmas that quota compliance presented to a party with a left-wing ideology, as well as the coordination challenges at several levels:

In our governorate, we present five lists … I am the second candidate on our list in [a big city]. The other municipalities are villages. We have one female top candidate [in the city], but we need at least one more. The party leadership said, ‘This is the law. If you don't present female top candidates, we will be rejected.’ … The local lists did not want to. … I witnessed tumultuous party meetings, where the leaders said, ‘but we are a left-wing party, we are progressive …’ And one list selector said, ‘Yes, I am progressive, but how do you want me to win in my village? Put a female top candidate on the urban list!’ Finally, they selected another village to have a woman top candidate, so now we have two women and three men. Then, we have to work on several levels; we must find another governorate where there are five municipalities with three female and two male top candidates. (IC9, candidate, Front Populaire)

Some small parties deliberately chose not to file some of their lists under the name of the party, but instead as independent lists, in order to circumvent the challenges related to horizontal gender parity – this is a phenomenon also described by Şaşmaz et al. (Reference Şaşmaz2018).

Horizontal parity is a strong constraint. For example, we have party lists and independent lists because we had a problem with horizontal gender parity. Because if not, we would have needed to change all the lists, all the top candidates, the whole machinery. So, for the lists where we had vertical parity, but not horizontal parity, we submitted them as independent lists. (IS1-5, party selector, Afek Tounès)

Note that it is not possible to identify such ‘disguised’ independent lists post hoc. A party selector from Afek Tounès estimated the number at ‘between 40 and 50’ (IS1-5, party selector, Afek Tounès). Thus, the party Afek Tounès could potentially have run with twice the number of lists. Instead, the electoral gains made in those disguised lists do not count towards the party's aggregated number of seats. Furthermore, campaign reimbursement will in such cases be channelled through the local lists (and the respective top candidates) instead of being distributed through the national party organization.

The reasons for non-compliance with the PwD quota are somewhat different. Interviewees mainly point to the form of the financial penalty tied to the quota. First, many independent lists did not expect to win enough seats to be entitled to reimbursement anyway (3% of votes per municipality).Footnote 7 Second, the campaign budget used by those lists was much lower than the budget of parties. Thus, few independent lists considered reimbursement and, hence, the identification and compliant placement of PwD candidates a priority.

We have a handicapped candidate, but not because he is handicapped. He is a real activist … This is why we chose him. (IC10, candidate, independent list)

Partial compliance: small parties and Nidâa Tounès

A second strategy corresponded to partial compliance with the quotas and aimed to implement all compulsory quotas (youth, vertical and horizontal parity) while leaving the implementation of the optional PwD quota up to the discretion of each individual list. This strategy was followed by some small parties and coalitions on their party lists and, most importantly, by Nidâa Tounès.

The small parties tried to act as strategically as possible to ensure the implementation of all compulsory quotas and avoid the rejection of any lists, of which they already had few. For example, a selector from the newly founded party Beni Watani reported that the leadership took advice where necessary, mainly making sure that, within the same governorate, HGP was fulfilled to avoid list rejection (IS6, selector, Beni Watani). Afek Tounès employed a more sophisticated system of candidate selection:

On average, we had to identify 30 candidates per list … so round about 3,000 in total. … To be honest, about half of the candidates we needed were party members but, afterwards, we discussed with independent people who agreed to be with us on the list. … However, the members and activists got the top positions. (IS1-5, party selector, Afek Tounès)

Another example of a small secular party is the Courant Démocrate. As in the above-mentioned examples, party selectors identified and recruited candidates on an ad hoc basis, reaching out not only to party members but also to their ‘contacts and acquaintances’. Again, selectors mentioned the quotas as the most important condition in candidate selection and placement, emphasizing that the main administrative task for the regional offices was to ensure horizontal parity by coordinating the party lists per governorate (IS7, selector, Courant Démocrate).

Concerning the PwD quota, representatives of small parties report that, even if the quota was fulfilled, there was a lot of bureaucracy involved in getting their campaign expenses reimbursed. This placed a significant burden on their administrative bodies. As the campaign relied mainly on the material and immaterial contributions of voluntary activists, ensuring reimbursement via quota compliance was not given priority. Therefore, little effort was made to seek out and strategically place candidates with disabilities.

The last party that often followed a partial compliance strategy was Nidâa Tounès. Reversing the small parties’ strategy of filing ‘independent’ lists, in many municipalities Nidâa offered resources to existing independent lists to persuade them to run under its party label.

In the beginning, our list was independent. One day, … the president of our list got a call from Nidâa Tounès and they asked him if he wanted to join the list to Nidâa Tounès and to receive the party support for the campaign. (IC11, candidate, Nidâa Tounès)

These existing lists already complied with the YQ and VGP. Nidâa's central party leadership would then change the order of candidates to ensure fulfilment of HGP (IS10, selector, Nidâa Tounès). This strategy explains Nidâa's comparatively high penetration rate as well as its high compliance rate with HGP. It also illustrates that even the second-largest party of Tunisia had difficulties strategically compiling lists. As a selector from Nidâa Tounès conceded, ‘we had neither the time nor the team to mount 350 lists from nothing’ (IS10, selector, Nidâa Tounès). Mirroring the ‘disguised independent list strategy’ of some small parties described above, Nidâa's strategy allowed the party to aggregate increased electoral gains and state funding under the party label.

Full compliance: Ennahda

Ennahda is the only party that followed a strategy of full compliance on almost all of its lists. In contrast to all other parties, the supply of candidates for Ennahda exceeded demand. The party reached out actively to non-party members, asking them to stand on its lists, and did this in good time before the election. While the task of identifying approximately 7,200 candidates seems challenging, party representatives said that they had received about 12,000 applications from potential candidates offering to stand for election. Ennahda was the only party to hold primaries in the summer of 2017. A party selector described the candidate selection process as highly inclusive and centralized.

In July 2017, the party leader called for candidate applications … We fixed dates for primary elections in each municipality. We invited all members of the respective local branches, but also independent citizens who were interested to stand as candidates on our lists. The local members selected a list with party members and a list with independents. In a municipality with 18 seats, they would choose nine members and nine independents. Then, there was a meeting in each local branch, with the party leadership and the local party members. We put together the list according to all requirements of the law, which is gender parity, the youth quota, and people with disabilities. … When the list was ready, we sent it to the regional party branch, which controlled it and made suggestions for change. The list was then transferred to the national executive office, who made final changes. Eventually, there were meetings with the local branches again, where all candidates on the list accredited the changes made. The top candidate signed the list and transferred it to the ISIE. (IS9, party selector, Ennahda)

This candidate selection process not only enabled Ennahda to comply with all quotas but was also by far the most internally democratic and transparent process.

Discussion and conclusion

The empirical evidence presented above provides two important insights that complement previous accounts on why parties do (not) comply with electoral quotas, while focusing on the electoral context of a new democracy. First, party ideology and willingness to comply did not seem to play an important role. While the quotas were designed in a way that effectively ensured that parties were willing to implement them – assuming that list rejection is the worst that can happen in an election – some parties were, apparently, unable to do so.

Second, as argued in the theoretical section of this article, parties’ organizational strength – the number and territorial spread of their members, as well as their human and financial resources – appears to be an important factor explaining variation in parties’ ability to comply with quotas (their compliance rates). As demonstrated, organizationally stronger parties had competitive advantages in candidate selection, candidate placement and the coordination of lists. This secured them a higher number of lists running, lower shares of rejection and greater state reimbursement.

The comparison of compliance rates not only between parties but also between quotas supports the theoretical suggestion that the strength of the quota system (i.e. the number of quotas and the strictness of their design) has a moderating function on the relationship between parties’ organizational strength and compliance rates. The high number of quotas operative in the Tunisian elections increased the general importance of organizational strength for aggregate compliance with (all) quotas, as weaker parties had to make decisions on which quota(s) they wanted to prioritize. They mostly chose those with a strict but ‘simple’ design (VGP, YQ), opting out of the most ambitious (HGP) and the less strictly designed (PwD). Conversely, we might expect that parties’ ability to comply is less important in the case of weaker quota systems (i.e. with fewer quotas and weaker sanctions), where willingness could again be hypothesized to be the decisive mechanism. However, this claim is tentative and would need further data in order to be tested.

The argument was developed based on an analysis of the 2018 Tunisian local elections. This certainly limits the generalizability of results. While Tunisia can be considered a typical case for a new democracy, the inductively generated results and hypotheses should be tested statistically and, ideally, cross-nationally. Furthermore, an important scope condition for the argument is a certain variation in parties’ organizational strength that we would not expect to encounter in established democracies. Here, most parties should be expected to be able to comply with most quota regulations, leaving willingness as the more important factor to look at.

Contributing to theory-building, this article has three main implications for the study of parties and quotas in new democracies in general and in the MENA region in particular. First, it contributes to the comparative research on electoral quotas. Regarding variation in quota compliance across parties, the article's results fit with previous empirical findings on parties’ compliance with electoral quotas in transitional democracies (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2016b) and electoral autocracies (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2016a) by focusing on the specific electoral context of new democracies.

Second, the article contributes to the scholarship on parties and party systems in the MENA region. While previous studies have primarily focused on ideological aspects of political competition in the region, this article offers a complementary perspective on their electoral strategies (Storm Reference Storm and Szmolka2017; Wegner and Cavatorta Reference Wegner and Cavatorta2019).

Third, the article reminds us that electoral engineering in the context of newly democratizing states is a powerful tool that will have effects beyond descriptive group representation (Dahlerup and Darhour Reference Dahlerup, Darhour, Dahlerup and Darhour2020). In particular, the findings should encourage policymakers to consider party system dynamics when engaging in electoral engineering. While quota designs need to be strict and ambitious to ensure both compliance and substantive gains in group representation, such designs also hold the potential to decrease political competition. Furthermore, financial sanctions for non-compliance may negatively affect novice parties’ further institutionalization. Dominant parties may benefit disproportionately from strict and complex quota systems, submitting more lists, winning more seats and aggregating more resources than smaller (opposition) parties. One potential solution to alleviate side effects on party and party system consolidation could be incremental quota designs that increase in strictness over time and leave parties more time to learn and adapt.

Supplementary material

To view the supplementary material for this article, please go to https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.34.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful for all comments received on previous versions of this article. Particular thanks go to the anonymous reviewers, as well as to all who have provided comments on conferences and workshops: among others Diana Z. O'Brien, Vibeke Wang, Ragnhild Muriaas and Raimondas Ibenskas. I also owe special thanks to my Tunisian friends and partners, Rim Kalai-Jemai and Bahia Bejar-Ghadhab. The research was conducted with support from the Norwegian Research Council under Grant No. 250669/F10.