Far-right parties have significantly increased their electoral support during the past decade (Mudde Reference Mudde2019). Although the rise of these parties has been underway in Western Europe since the early 1990s (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, De Lange and Rooduijn2016; Golder Reference Golder2016), it recently became a worldwide phenomenon. The economic crisis in 2008 acted as a catalyst and generally increased these parties’ performance further all over Europe (Algan et al. Reference Algan, Guriev, Papaioannou and Passari2017; Kriesi and Pappas Reference Kriesi and Pappas2015; Zagórski et al. Reference Zagórski, Rama and Cordero2019). This trend has been accompanied by the electoral decline of mainstream parties from both the left and right – social democrats and Christian democrats.

Consequently, party systems of several countries went through significant changes. The far right has moved from the margins to the mainstream and disrupted long-established patterns of party competition (Mudde Reference Mudde2019; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). At the same time, some mainstream conservatives have become far right themselves: prominent examples are Fidesz in Hungary and Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland, which initially gained electoral successes as conservative parties and then radicalized their rhetoric and policies (Bustikova Reference Bustikova and Rydgren2018; Stanley Reference Stanley, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017).

Moreover, scholars point out that the salience of the traditional socioeconomic left–right cleavage has faded over time, and the cultural divide between those who advocate open borders and those who defend border closure has become dominant (De Wilde et al. Reference De Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). Nonetheless, it is difficult to disentangle current economic and cultural debates. A good illustration is how economic problems are instrumentalized to advocate moral positions by Fidesz. Its leader Viktor Orbán proclaimed that the economic crisis demonstrated the ‘failure of liberal democracy’ (Gessler and Kyriazi Reference Gessler, Kyriazi, Hutter and Kriesi2019).

Admitting the challenges far-right parties pose to liberal democracy, many scholars have investigated the profile and motives of their supporters. The literature commonly distinguishes between grievances arising from economic change, cultural conflict and political disillusionment. Similarly, this article combines three explanatory approaches and focuses on socioeconomic deprivation, opposition to progressive values (such as cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism) and protest against political elites (Golder Reference Golder2016; Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019).Footnote 1

Prior research predominantly focused on Western Europe (for reviews, see Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren2018; Golder Reference Golder2016; Muis and Immerzeel Reference Muis and Immerzeel2017). It concludes that the main predictor of far-right voting is nativism, particularly anti-immigration views. Attitudes pertaining to economic issues have less explanatory power (Cavallaro and Zanetti Reference Cavallaro and Zanetti2020). Yet, we do not know whether this is equally true in Central and Eastern Europe (hereafter: CEE). Moreover, most previous studies made a simple dichotomy between far-right voters and all other voters (e.g. Eger and Valdez Reference Eger and Valdez2015; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2017; Werts et al. Reference Werts, Scheepers and Lubbers2012; Zagórski et al. Reference Zagórski, Rama and Cordero2019). The important question remains whether these conclusions hold if we do not lump all other voters together.

This article adopts an innovative approach to individual-level explanations for far-right support by making two novel comparisons. First, what distinguishes far-right voters from voters for other party families and abstainers? In their comparative study of nine Western European countries, Daniel Oesch and Line Rennwald (Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018) argue that three party blocs can be distinguished based on parties’ ideology: the left, the centre right and the far right. Accordingly, we compare far-right voters with traditional left-wing voters (including socialist and social democratic parties) and centre-right voters (including Christian democratic and conservative parties). By doing so, our results indicate more clearly which parties compete with far-right parties on which issues. Comparing far-right supporters with moderate-right voters is interesting because of the related conservative party ideology of centre-right parties (Immerzeel et al. Reference Immerzeel, Lubbers and Coffé2015). A comparison between far-right voters and traditional left-wing parties is equally interesting because the socioeconomic status of supporters of both types of parties is similar (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018).

We also include abstainers (see Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2014), because not all people respond to dissatisfaction with political radicalism (i.e. far-right voting). Another important option is to withdraw from political participation (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marien and Pauwels2011). Jens Rydgren (Reference Rydgren2011) defines that contrast as the choice between ‘voice’ and ‘exit’.Footnote 2

Our second contribution is that we compare mature and post-communist democracies. Are the above-mentioned three explanations for far-right voting equally valid for CEE? Our aim is thus to investigate whether the appeal of far-right parties in post-communist democracies can be explained by theories acquired from studies on mature democracies (see Allen Reference Allen2017b). Until recently, scholars have often ignored the post-communist region (Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2017; Pirro Reference Pirro2014a; Pytlas Reference Pytlas2016). Some studies included both Western and Eastern European countries (e.g. Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), but neither explain nor demonstrate whether far-right voting is driven by the same reasons in the two regions. This comparison is interesting because of the persisting political and socioeconomic differences between the two regions, primarily inflicted by the legacy of communist rule and traumatic post-communist transformation in CEE (Gaidytė Reference Gaidytė2015; Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2017).

Analysing attitudes and voting behaviour in 17 countries covered in the European Social Survey (ESS) in 2014 and 2016, we find that anti-immigration attitudes are most important in distinguishing far-right voters from all other groups in both mature and post-communist democracies. Yet, these differences are significantly smaller in CEE. Socioeconomic deprivation appears less important: far-right voters are not the so-called socioeconomic ‘losers of globalization’; this is only true when we compare them with centre-right voters. Concerning protest voting, we show that distrust of supranational governance particularly enhances far-right voting. Distrust of national politics is, however, not systematically related to electoral support for far-right parties.

Overall, we conclude that far-right voters generally resemble non-voters and voters of traditional left-wing parties in terms of socioeconomic deprivation, and resemble those of centre-right parties where authoritarian values are concerned. In sum, our study demonstrates that more fine-grained comparisons avoid making the misleading generalizations about ‘European far-right voters’ often presented in public debates.

Theoretical background: who votes for far-right parties?

Scholars use different labels for the same new right party family in Europe, such as ‘extreme right’ (Bale Reference Bale2003), ‘radical right’ (Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren2018) and ‘populist radical right’ (Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2017). In line with, among others, Cas Mudde (Reference Mudde2019), we use the label ‘far right’. The core focus of the European far-right family is nationalism and potential threats to national values and identity (Bar-On Reference Bar-On and Rydgren2018; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2017). In this regard, far-right parties are not promoting a fundamentally different ideology from many mainstream parties, but rather adopt a more radical version of it.

It is important to stress that ‘far right’ does not necessarily imply ‘populist’. Populism is a political discourse which puts ‘the pure people’ against the allegedly corrupt establishment (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Who belongs to ‘the people’ is often only vaguely described. Whereas Jan-Werner Müller (Reference Müller2016: 3) argues that the definition of populism implies ‘an exclusionary form of identity politics’, other scholars distinguish exclusionary, right-wing populism from populist parties with an inclusionary, left-wing worldview (Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2017). In any case, it is ‘misleading’ to call contemporary far-right parties ‘populist parties’, since ‘populism is not the most pertinent feature of this party family’ (Rydgren Reference Rydgren2017: 486).

‘Cultural backlash’: threatened national identity and traditional values

The dominant approach for explaining far-right support focuses on what Piero Ignazi (Reference Ignazi1992) famously labelled a ‘silent counter-revolution’ against the rise of progressive values. Far-right parties appeal to certain segments of the population because they promote law and order, the restoration of traditional social values, ‘an aggressive nationalism’ and ‘xenophobic policies against immigrants’ (Ignazi Reference Ignazi1992: 21). Similarly, the ‘cultural backlash thesis’ interprets far-right support as a reaction against sociocultural changes, such as increasing multiculturalism and the rise of libertarian values (Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2017; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Many cultural approaches include similar arguments, but one element stands out: hostility towards immigration. Scholars sometimes adopt the broader term nativism, which can be summarized by the slogan ‘own people first’ (Bar-On Reference Bar-On and Rydgren2018). Originally developed to analyse anti-immigrant sentiments in the US and Canada, the term has been increasingly used to understand the fortunes of the far right elsewhere (Betz Reference Betz2019).

Anti-immigration attitudes can stem from both perceived symbolic threats and instrumental concerns (Lucassen and Lubbers Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), although citizens perhaps do not clearly distinguish between cultural and economic grievances (Golder Reference Golder2016). In any case, opposition to immigration is the core motivation for people to vote for far-right parties: many scholars have demonstrated that anti-immigration attitudes constitute the main explanation for electoral support for far-right parties in Western Europe (Iversflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2005, Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Oesch Reference Oesch2008). The dominance of this explanatory factor is underlined by the fact that some scholars prefer the label ‘anti-immigrant’ parties (Van der Brug and Fennema Reference Van der Brug and Fennema2007).

Tim Immerzeel and Mark Pickup (Reference Immerzeel and Pickup2015) argue that the supply of a nativist ideology has attracted support for the far right from people who would not otherwise turn out to vote. It can thus be assumed that abstainers feel less often that national identity is threatened than far-right voters. Empirical research on Western Europe indeed shows that anti-immigrant attitudes among far-right voters are significantly stronger than among abstainers (Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2014).

Are electoral successes of the far right in CEE also best understood through the lens of nativism? Ethnic diversity is a prominent societal fact in the West, compared with the generally more homogeneous societies in the East (despite some notable exceptions). Although ethnic nationalism is widespread, until recently immigration has not been an important issue (Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2017). Andrea Pirro (Reference Pirro2014b: 247) points out: ‘Appraising the electoral performance of these parties in terms of a native backlash against the immigrant population serves poorly as an explanation in countries where immigration does not represent a salient issue.’

However, Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes (Reference Krastev and Holmes2018: 126) point out that perceived fear of an influx of foreigners can be as ‘real’ as the actual experience of ethnic diversity in the West. They argue that ‘anti-immigrant hysteria’ in the face of a non-existent immigrant invasion is rooted in more realistic demographic anxieties related to the mass outmigration from the post-communist region, especially of skilled young people. Moreover, fear of ethnic diversity is created by pointing to the West as an example of how things can go wrong. To conclude, we expect that anti-immigration attitudes are most important in explaining far-right support in Europe, but that the differences between far-right voters and other citizens are greater in the West than in the East:

Hypothesis 1a: In both post-communist and mature democracies, far-right voters have stronger anti-immigration attitudes than centre-right voters, left-wing voters and abstainers.

Hypothesis 1b: In post-communist democracies, anti-immigration attitudes have a weaker effect on electoral support for far-right parties than in mature democracies.

We focus on authoritarianism as the other main manifestation of cultural grievances (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2011; Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2014). Mudde (Reference Mudde2007: 221) argued that authoritarianism is ‘the second most important attitudinal variable’ in explaining far-right voting that is related to the sociocultural dimension (after nativism). Adherence to authoritarian values reflects a belief in a strictly ordered society and protecting traditional values (Oesch Reference Oesch and Rydgren2012; Pirro Reference Pirro2014b). Far-right parties in both East and West promise to uphold and restore traditional sociocultural values (Golder Reference Golder2016; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2017). Strong political leaders are assumed to secure safety for ‘the people’ (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008).

Kris Dunn's (Reference Dunn2015) study of five Western European countries found, however, that authoritarianism is not significantly related to far-right support. This could be due to the fact that mainstream conservative right parties also promote law and order, national unity and culturally conservative views. They have adopted some of the sociocultural issues of the far right, for instance tough policies on crime (Bale Reference Bale2003; Immerzeel et al. Reference Immerzeel, Lubbers and Coffé2015). For this reason, Immerzeel et al. (Reference Immerzeel, Lubbers and Coffé2015) claim that centre-right parties are more likely to compete electorally with far-right parties than with left-wing parties. Consequently, we refine the cultural backlash thesis: we expect that authoritarianism does not significantly distinguish between voters of conservative parties and of far-right parties, but more specifically explains why people support the far right, rather than left-wing parties or abstain.

We likewise expect that there are hardly any differences in this respect in Eastern Europe between supporters for far-right and centre-right parties. People generally more strongly endorse traditional values and oppose cultural progressiveness than in Western Europe (Kochanowitcz Reference Kochanowicz and Markova2004; Krastev and Holmes Reference Krastev and Holmes2018). Given this, mainstream right-wing parties often rally around the same law-and-order issues and we therefore similarly expect that authoritarian citizens do not necessarily vote for far-right parties, since they could also opt for centre-right parties. Hence:

Hypothesis 2: In both post-communist and mature democracies, far-right voters more strongly support authoritarianism, but only in comparison with left-wing voters and abstainers.

Socioeconomic deprivation

The second approach focuses on economic grievances. Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019) explain far-right support through the rise of global markets, which increasingly divide the ‘winners’ from the ‘losers’. The latter experience low employment, have lower incomes and face more economic insecurity (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). Economic and cultural explanations are, however, hard to distinguish; often a combination of the two is used to explain far-right voting. This is manifested most clearly in ethnic competition theory. According to this theory, people adopt anti-immigrant views when they perceive that they are competing with immigrants for scarce resources (Golder Reference Golder2016; Lubbers et al. Reference Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers2002). This is closely related to ‘welfare chauvinism’, the notion that only natives should benefit from welfare programmes and that foreigners should be excluded (Oesch Reference Oesch2008).

Matt Golder (Reference Golder2016: 484) points out that ‘there is considerable evidence in support of the economic grievance story at the individual level’. Previous studies repeatedly showed that people who vote for far-right parties are more often from lower socioeconomic groups. They apparently feel less represented by established parties, which presumably convey the interests and preferences of the higher-educated ‘winners’ (Bovens and Wille Reference Bovens and Wille2017; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008).

However, most studies contrast far-right voters with all other voters. As already explained, we make a more detailed comparison and argue that economic deprivation accounts only explain why the electoral appeal for social democrats has declined. Kirill Zhirkov (Reference Zhirkov2014) showed that far-right voters have similar characteristics to voters for left-wing parties in terms of their socioeconomic status, but differ from centre-right parties. Consequently, left-wing parties are particularly vulnerable to losing voters to the far right (Oesch Reference Oesch2008; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018; Rydgren Reference Rydgren and Rydgren2013). Moreover, those who abstain from voting are also believed to have similarly lower levels of education and a lower socioeconomic status (Allen Reference Allen2017a). Hence, we expect that the widely used ‘losers of globalization’ argument is conditional: economic deprivation indeed demarcates far-right voters from centre-right voters, but fails to explain far-right voting if we compare far-right voters with traditional left-wing voters and abstainers.

We expect a similar pattern with regard to attitudes towards welfare policies. Herbert Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt1995) famously argued that combining free market liberalism with sociocultural authoritarianism is the ‘winning formula’ for far-right parties. However, scholars have argued and demonstrated that most Western European far-right parties have actually blurred positions on the socioeconomic dimension (Betz Reference Betz2004; Rydgren Reference Rydgren and Rydgren2013), despite the fact that some of them participated in centre-right coalitions.

There is scant evidence for the influence of attitudes on income redistribution on far-right voting. Maureen Eger and Sarah Valdez (Reference Eger and Valdez2015) found that support for income redistribution does not affect the odds of voting for far-right parties in Western Europe. Similarly, Trevor Allen (Reference Allen2017a) found no effect. Again, these non-findings might be due to the fact that far-right supporters were contrasted with all other voters. Since Western European far-right parties have turned into ‘a new type of working-class party’, according to Oesch (Reference Oesch and Rydgren2012: 48), we would only expect differences between far-right voters and centre-right voters.

We expect similar patterns in post-communist countries. Far-right parties in Eastern Europe are generally left-leaning on the economy, even more than in the West (Bustikova Reference Bustikova and Rydgren2018). In terms of the supply side, the post-communist far right is thought to capitalize successfully on economic grievances surrounding welfare retrenchment (Bustikova and Kitschelt Reference Bustikova and Kitschelt2009). In post-communist party systems, those who are less educated – sometimes labelled as ‘losers’ of the transition – still expect (despite the collapse of communism) the state to provide extensive social welfare (Allen Reference Allen2017b; Polyakova Reference Polyakova2015). We hence expect that in terms of socioeconomic background and attitudes to redistribution, we will observe a similar overlap between far-right voters and left-wing voters and abstainers as in Western Europe, and only pronounced differences between centre-right and far-right supporters. Therefore:

Hypothesis 3: In both mature and post-communist democracies, far-right voters belong to lower socioeconomic status groups, but only when compared with centre-right voters.

Hypothesis 4: In both mature and post-communist democracies, far-right voters are more strongly in favour of income redistribution, but only when compared with centre-right voters.

Political disillusionment: protest voting

Protest vote explanations imply that cynicism and discontent with politics motivate people to vote for far-right parties (Dalton and Weldon Reference Dalton and Weldon2005; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2017; Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2000). As Grigore Pop-Eleches (Reference Pop-Eleches2010: 223) puts it: ‘Protest voting is the practice of voting for a party not because of the actual content of its electoral message but in order to “punish” other parties.’ Empirical evidence from Western Europe shows that individuals who are dissatisfied with politics vote for far-right parties as a token of protest (Norris Reference Norris2005). Similarly, it is argued that low political trust facilitated populist parties in post-communist countries to attract substantial electoral support (Algan et al. Reference Algan, Guriev, Papaioannou and Passari2017). Distrust could have different underlying reasons. Conrad Ziller and Thomas Schübel (Reference Ziller and Schübel2015), for instance, find that exposure to corruption diminishes political trust, which in turn leads to a greater propensity to vote for far-right parties.

Declining political trust has not only been observed at the national level, but also at the supranational level (Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Van der Meer and De Vries2013; Hay Reference Hay2013). The latter is, for instance, conceptualized as trust in the United Nations and European Parliament, which has possibly different effects on far-right voting compared with trust in national institutions. Regarding the supply side, far-right parties indeed have eurosceptic attitudes; they are against European economic collaboration and cultural integration (Pirro Reference Pirro2014b; Werts et al. Reference Werts, Scheepers and Lubbers2012). Han Werts et al. (Reference Werts, Scheepers and Lubbers2012) show that euroscepticism is an important explanation for far-right voting, and, moreover, that the effect is comparable in East and West.

Furthermore, studies show mixed results when comparing the degree of political trust between far-right voters and abstainers. For example, Russell Dalton and Steven Weldon (Reference Dalton and Weldon2005) show that abstainers have lower levels of political trust than far-right voters, whereas other studies revealed no differences in levels of political trust between non-voters and far-right voters (Allen Reference Allen2017a; Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2014).

After political trust, political efficacy explains why people vote and which party they choose (Pateman Reference Pateman1970; Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). It defines how individuals perceive the responsiveness of politicians, and whether the political system provides a place for the individual to contribute (Niemi et al. Reference Niemi, Craig and Mattei1991; Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Otto, Alings and Schmitt2014). As with the influence of political distrust, voters for far-right parties have a stronger feeling that their voice is not heard and that political elites ignore ‘ordinary citizens’, compared with voters of other parties (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, Van der Brug and De Lange2016).Footnote 3

We expect similar associations between political trust and external efficacy and far-right voting in both the West and the East. People in post-communist societies inherited generally low levels of political trust from the communist past. Political trust was further undermined by the weakness of the institutions in shaping the transition to democracies (Howard Reference Howard2003; Szelenyi and Wilk Reference Szelenyi, Wilk, Morgan, Campbell, Crouch, Pedersen and Whitley2010). Similarly, the feeling that one can influence political outcomes – external efficacy – of post-communist citizens is also generally rather weak (Mierina Reference Mierina2011). Consequently, populist rhetoric has not been adopted exclusively by right-wing parties; left-wing and centre parties also frequently campaigned on anti-corruption issues and dissatisfaction with political elites (Hanley and Sikk Reference Hanley and Sikk2016). Nevertheless, since nativism is often bundled together with sentiments against the political elites ‘that sold national interests to outsiders, foreigners and ethnic minorities’ (Bustikova Reference Bustikova and Rydgren2018: 571), we expect that anti-elitism is predominantly associated with far-right voting. Thus, we formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5: In both mature and post-communist democracies, voters for far-right parties have less trust in national and supranational political institutions than centre-right and left-wing voters do. However, they do not differ from those who abstain.

Hypothesis 6: In both mature and post-communist democracies, voters for far-right parties have lower levels of external political efficacy than centre-right and left-wing voters. However, they do not differ from those who abstain.

To conclude, an overview of our hypotheses is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of our Hypotheses

Note: *Yes, and interaction effect: the differences are smaller in East than in West (H1b).

Research design

Data and case selection

This study uses ESS data for 2014 and 2016 (rounds 7 and 8). As already explained, we investigate whether Western European far-right electorates are similar to their counterparts in post-communist Europe, or whether electoral support for this party family requires a region-specific explanation.Footnote 4 The Western European democracies in our sample are: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany,Footnote 5 the Netherlands, Norway, the UK, Sweden and Switzerland. We include the following post-communist democracies: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Slovenia. Except for Denmark, all countries participated in both ESS waves. We decided to use only the two most recent waves of ESS data (i.e. 2014 and 2016) because we focus on contemporary Europe. Extending the period under study would add a temporal dimension and thus require an additional comparative perspective; the importance of the three explanations (economic deprivation, cultural conflict and political disillusionment) could have changed over time.

Dependent variable

Following Zhirkov (Reference Zhirkov2014), we distinguish four groups of respondents. First, respondents are grouped into those who participated in the last national elections and those who abstained. Respondents who were not eligible to vote are excluded from the analysis. Subsequently, voters are grouped into three categories: far right, centre right (including Christian democrats and conservatives, see online Appendix A), and traditional left-wing (including socialists and social democrats, see online Appendix B). Our operationalization of party families is based on Immerzeel et al. (Reference Immerzeel, Lubbers and Coffé2015).

Furthermore, we excluded respondents who voted for parties that were difficult to classify (see Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). We excluded the new left parties (such as Green parties) from the old left-wing party family, since they differ in some fundamental respects: they are exceptionally popular among sociocultural professionals and do not fare well among the working class, whereas social democratic parties are the most popular among production and service workers (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018).Footnote 6

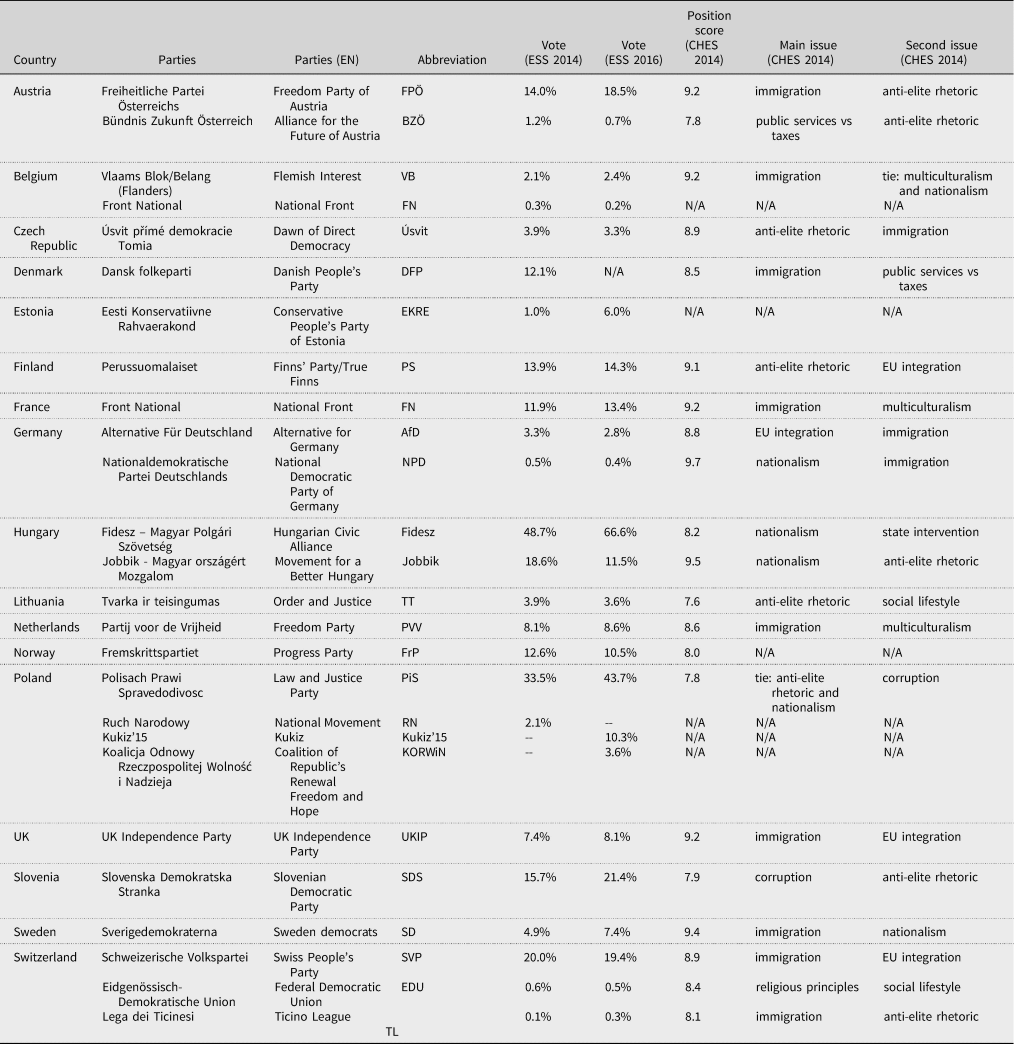

Table 2 shows the parties we denote as far right. This study updates the selection of Immerzeel et al. (Reference Immerzeel, Lubbers and Coffé2015). Most importantly, we include Law and Justice (PiS) and Fidesz. Although both parties were often considered to be conservative right-wing parties, scholars increasingly define them as ‘radicalized parties’ (Bustikova Reference Bustikova and Rydgren2018). For instance, Michael Minkenberg (Reference Minkenberg2017: 124) describes them as ‘right-wing populist with programmatic elements of radical right’. We similarly argue that they have transformed from conservative right to far right (see Gómez-Reino and Llamazares Reference Gómez-Reino and Llamazares2013; Stanley Reference Stanley, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017).

Table 2. Far-Right Parties of the 16 Investigated Countries

Source: ESS (2014 and 2016).

Note: N/A means the country or party is not available in ESS or in CHES.

We used the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) from 2014 (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2014) to cross-validate our far-right classification. Following Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019: 233), we constructed an authoritarian–libertarian scale consisting of seven items (galtan, nationalism, civlib_law and order, multiculturalism, social lifestyle, immigration policy, ethnic minorities) that indicate parties’ positions on sociocultural issues (Cronbach's α = 0.97; N parties = 267). These measures include whether parties favour traditional social values, promote nationalism and restrict immigration and are measured on a scale from 0 (libertarian-cosmopolitan) to 10 (authoritarian-nativist). Table 2 shows that all the far-right parties we included score 7.5 or higher on this scale.

Not all parties that score 7.5 or higher are included in our selection, because issue salience also matters. According to Tjitske Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, De Lange and Rooduijn2016), among others, the label ‘radical’ not only refers to an extreme position, but also implies salience. Hence, we examined the two most important issues of the party in question, according to the CHES (see Table 2). Issue salience clarifies why a few parties with a score of 7.5 or higher are nevertheless usually not considered as far-right parties, such as the orthodox Christian Political Reformed Party (8.6) in the Netherlands – its two main issues are ‘religious principles’ and ‘public services vs taxes’. For the same reason, parties such as the German Christian Democratic Union (7.4) and French Union for a Popular Movement (7.4) are distinguished from the far right, although they score relatively high on the sociocultural dimension: they neither stress authoritarian-nativist issues, nor anti-elitism. In contrast, Table 2 shows that all our selected parties have a strong authoritarian-nativist position (7.5 or higher) and deem anti-elitism and/or authoritarian-nativist issues to be important.Footnote 7

Finally, we should point out that only adopting anti-elite rhetoric is not sufficient for a party to be labelled ‘far right’. For instance, we did not include ANO (Action of Dissatisfied Citizens), established by the Czech businessman Andrej Babiš. The party is centrist anti-establishment/populist rather than far right (Hanley and Sikk Reference Hanley and Sikk2016; Van Kessel Reference Van Kessel2015). We therefore classify it as centre right (its authoritarian-nativist score is 4.8). Our collection of traditional left-wing parties also includes some ‘anti-establishment’ parties, such as Die Linke in Germany (Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2017).

Table 3 shows the distribution of the four groups. It shows that in post-communist countries, non-voters form the largest group (39.1%) of respondents, whereas voters for centre-right parties constitute the largest group in Western Europe (41.6%). In our sample, the share of far-right voters is substantially higher in CEE (15.7%) than in Western Europe (8.6%).

Table 3. Respondents’ Distribution per Group

Source: ESS (2014–16).

Explanatory variables

All details on the measurements of the variables, including question wordings and answer categories, are presented in online Appendix C. The descriptive statistics and reliability coefficients (Cronbach's α) are depicted in online Appendix D.

Cultural backlash

First, anti-immigration attitudes is a scale consisting of three questions. The questions ask if immigrants are ‘good or bad for the economy’, ‘undermining or enriching cultural life’ and ‘make the country a better or worse place to live in’. The answer categories run from 0 to 10. A higher score represents stronger anti-immigration attitudes. Following, among others, Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019) and Werts et al. (Reference Werts, Scheepers and Lubbers2012), citizens’ adherence to authoritarian values is operationalized by four questions about topics concerning law and order. Respondents were, for instance, asked to what extent the government needs to ensure safety against threats and whether traditions are important.

Socioeconomic status

Three variables are used. First, respondents’ perceived adequacy of income is asked, which measures the capacity to live with one's current income. Answers ranged from ‘very difficult’ (1) to ‘living very comfortable on present income’ (4). Unfortunately, although it would be preferable to have an indicator of objective financial deprivation in addition to subjective deprivation, the number of missing cases of the income variable is rather large. Both dimensions could indeed differently affect voting behaviour. Nevertheless, both in mature democracies and in post-communist democracies the income decile correlates with the perceived income (r = 0.47/0.49, p < 0.01). Second, educational level is measured using the International Standard Classification of Education, which ranges from 1 to 7. Third, unemployment is used as proxy of socioeconomic deprivation (Allen Reference Allen2017b; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995). Furthermore, respondents’ support for income redistribution is measured with the item ‘government should reduce differences in income’. The answer categories range from ‘disagree strongly’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5).

Protest voting

First, national political trust is operationalized by five questions regarding trust in national political institutions, such as the parliament and legal system. The scale ranges from 0 (‘no trust’) to 10 (‘complete trust’). Supranational political trust measures trust in the European Parliament and the United Nations (two questions). Next, the measurement of external political efficacy also consists of two items. An example of a question is: ‘How much would you say that politicians care what people like you think?’.Footnote 8 Finally, we included two sociodemographic factors as control variables, namely, age and gender.

As we explained earlier, it is difficult to draw strict distinctions between cultural, economic and political grievances. The correlation matrix (see online Appendix E) shows how they are related. As one would expect based on existing studies (Mayda Reference Mayda2006), cultural backlash is associated with socioeconomic deprivation. People with lower perceived incomes have stronger anti-immigration attitudes, in both mature (r = −0.20) and post-communist democracies (r = −0.17). Education level has a similar negative relationship.

Furthermore, we find a negative relationship between socioeconomic status and political disillusionment: the higher one's perceived income and education level, the more favourable one's opinions about politics. Finally, the strongest associations exist between the indicators of political and cultural grievances, especially in Western Europe. For instance, the more negative one's attitudes towards immigrants, the less trust one has in national and supranational politics (mature democracies: r = −0.43/−0.40; post-communist democracies: r = −0.17/−0.25).

Findings

We conducted multilevel multinomial logistic regressions, with the four different groups as the dependent variable: far-right voters, traditional left-wing voters, centre-right voters and abstainers.Footnote 9 The results are presented in Table 4 (mature democracies) and Table 5 (post-communist democracies).Footnote 10 We show both the estimates and changes in predicted probabilities. Far-right voters are the reference category. A negative estimate thus indicates a higher score on the respective variable: the more likely it is that one votes for the far right, rather than respectively for a centre-right party, a traditional left-wing party, or abstains from voting. The change in the predicted probability is calculated when the respective independent variable changes from the lowest to the highest value (min/max).Footnote 11 For instance, Western Europeans who live very comfortably on their present income have a 10 percentage points higher likelihood of voting for the centre right than for the far right than people who find it very difficult to live on their current income.

Table 4. Multilevel Multinomial Logistic Regression: Mature Democracies

Note: Far-right voters are the reference category. Coefficients in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05, two-tailed).

Table 5. Multilevel Multinomial Logistic Regression: Post-Communist Democracies

Note: Far-right voters are the reference category. Coefficients in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05, two-tailed).

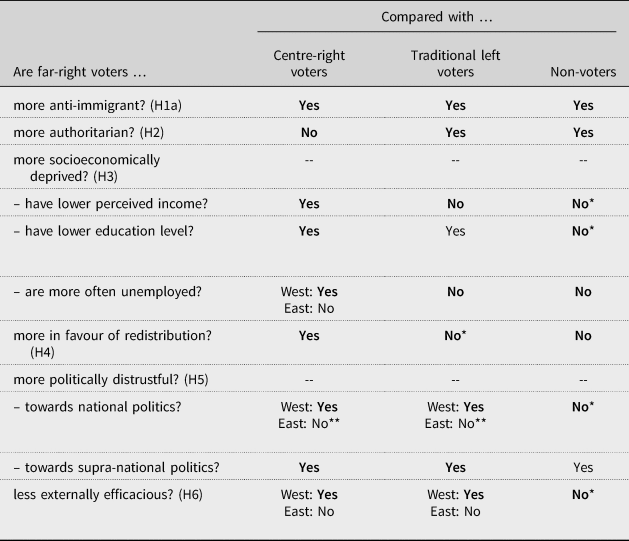

Our results are summarized in Table 6. The first finding stands out: as expected, anti-immigration attitudes are consistently related to electoral support for the far right (support for H1a), unlike other explanatory factors. They most importantly account for differences between far-right voters and the other three groups of citizens. In Western Europe, the likelihood differences range from 48 percentage points (compared with centre-right voters) to 68 percentage points (compared with left-wing voters).

Table 6. Summary of our Findings

Notes: Bold means in line with our hypothesis.

* There is a significant effect in the opposite direction (we expected ‘No’).

** There is a significant effect in the opposite direction than expected (we expected ‘Yes’).

The impact of anti-immigration attitudes is less pronounced in post-communist democracies (tentative support for H1b). If we contrast people with the most positive and most negative attitudes towards immigration, the predicted probability of far-right voting decreases by 22 percentage points (compared with abstaining), 34 percentage points (compared with voting for left-wing parties) and 37 percentage points (compared with voting for the centre right), which are weaker effects than we observed in mature democracies. We will return to a formal test of the moderation effect of region (H1b) later.

Our authoritarian hypothesis (H2) is also supported for both mature and post-communist democracies, due to the observed similarities between far-right voters and centre-right voters in their adherence to authoritarian values. In contrast, far-right voters are indeed significantly more authoritarian when we compare them with abstainers and left-wing voters. These results confirm Dunn's (Reference Dunn2015) conclusion that authoritarianism is not a consistent predictor of far-right support.

Next, the socioeconomic deprivation hypothesis (H3) is largely confirmed. In Western Europe, far-right voters have a lower perceived income, are more often unemployed and are lower educated than the centre-right voters. In post-communist democracies far-right voters are likewise less educated and have lower perceived incomes than centre-right voters. Unemployment is not linked with far-right voting in Eastern European democracies.

As we expected, our results demonstrate that in both mature and post-communist democracies far-right voters are not socioeconomic ‘losers’ if we compare them with traditional left-wing voters and abstainers. In both country-sets, perceived income ranks the far-right voters with the left-wing voters, in line with Oesch (Reference Oesch2008). Furthermore, far-right voters are not more often unemployed than abstainers and left-wing voters. The only minor deviation from our socioeconomic deprivation hypothesis is that far-right voters are lower educated than left-wing voters.

If any group stands out as the socioeconomic underclass, it is the abstainers. In both regions, they are less educated and have lower perceived incomes than far-right voters. The likelihood of voting for the far right (rather than abstain) is about 13 (Western Europe) and 4 (CEE) percentage points higher for people who report they are able to live comfortably on their current income compared with those who consider this very difficult.

Next, in line with our income redistribution hypothesis (H4), far-right voters in both regions more strongly support income redistribution than centre-right voters. Moreover, as we expected, abstainers do not differ significantly from far-right voters, which contradicts Allen's (Reference Allen2017a) findings (he studied mature democracies). In contrast to our expectation, far-right voters in both regions differ significantly from left-wing voters: they oppose income redistribution more strongly. Thus, overall, far-right voters are neither economically right nor left.

We finally evaluate the third approach – protest voting – to explain far-right support. Our expectations are corroborated in Western European democracies: far-right voters have less trust in national political institutions (H5) and perceive less external efficacy (H6) compared with centre-right and left-wing voters. Moreover, abstainers have low levels of political trust similar to far-right voters. This finding resembles Zhirkov's (Reference Zhirkov2014) results, but contradicts Dalton and Weldon (Reference Dalton and Weldon2005). Likewise, far-right supporters and non-voters in Western Europe think that politicians are unresponsive to the demands of citizens to the same degree. This corresponds with findings of Eefje Steenvoorden and Eelco Harteveld (Reference Steenvoorden and Harteveld2018).

As we expected, distrust of politics is likewise important at the supranational level. Indeed, Western European far-right voters have less trust in supranational institutions (Werts et al. Reference Werts, Scheepers and Lubbers2012), not only compared with centre-right voters and left-wing voters, but also in comparison with the abstainers.

Shifting our focus to post-communist democracies, we surprisingly find that far-right voters have more trust in national politics when compared with all other groups (rejecting H5). We will come back to this remarkable finding later. Far-right voters in CEE also perceive significantly higher levels of external efficacy than abstainers and left-wing voters (rejecting H6). In fact, some effects seem rather strong. The likelihood of voting for the far right, rather than for left-wing parties, is about 50 percentage points higher for those who have most trust in national politics than for those who are most distrustful; compared with centre-right voters, this difference is 38 percentage points.

To sum up, our results show that discontent with politics in post-communist democracies is not only, and not predominantly, rooted in far-right voters, but is also rooted in other voters and particularly the abstainers. Interestingly, however, we observe the opposite pattern when considering trust in supranational governance: like their counterparts in Western Europe, CEE far-right voters are more distrustful of the EU and UN, compared with all other groups. The findings supports Lenka Bustikova's (Reference Bustikova and Rydgren2018) claim that eurosceptic attitudes bridge East–West differences among the far right.

Finally, let us return to the only variable that – together with distrust in supranational government – consistently relates to far-right voting: anti-immigrant attitudes. We ran an additional regression model with all countries pooled together in which we included an interaction term in addition to all independent variables (results are shown in online Appendix F). The results show that the effects of anti-immigrant attitudes on far-right voting are indeed significantly stronger in the West than in the East, thus supporting H1b. This finding confirms Allen (Reference Allen2017b).

To assess whether particular countries drive these results, we show the country-by-country results in Figure 1. They reassert that the effects of anti-immigration attitudes are generally weaker in the post-communist countries. A notable exception is Estonia, where anti-immigration feelings are relatively strong determinants of support for the EKRE (but see Trumm Reference Trumm2018). At the other end, the case of Lithuania reveals insignificant effects – apparently, it is rather hard to predict support for Order and Justice (TT), since most other predictors are also irrelevant. These findings indeed relate to the supply-side issue of party classification: one would expect weaker effects in countries where far-right parties do not have an openly nativist agenda and where mainstream parties are less reluctant to adopt far-right themes and are tough on immigration (Bale Reference Bale2003). Finally, it is important to note that our conclusion of weaker effects does not imply that the level of anti-immigration attitudes is lower in the East than in the West – in fact, the opposite is true (see online Appendix D).

Figure 1. Country-by-Country Analysis of the Effect of Anti-Immigrant Attitudes: Far-right voters are the reference category

Finally, Figure 2 summarizes the different impacts of anti-immigrant attitudes on far-right voting in Western and Eastern Europe. It shows that among those who have the most positive attitudes towards immigrants, hardly anyone in Western Europe votes for the far right; by contrast, the predicted probability in post-communist countries is about 17%. For people with the strongest anti-immigrant attitudes, the predicted probability of voting for the far right is about 35% (Western Europe) and 26% (Eastern Europe). The contrast is thus much more pronounced in Western Europe.

Figure 2. Predicted Probabilities of Belonging to Each of the Four Groups (Far-Right Voters, Centre-Right Voters, Left-Wing Voters, Non-Voters), for Each Level of Anti-Immigrant Attitude

It is interesting to note that in Western Europe the probability that one votes for a left-wing party dramatically decreases if anti-immigrant sentiments increase, whereas in post-communist democracies the probability of voting for left-wing parties hardly changes. In contrast, if we consider centre-right parties, our results show that anti-immigrant attitudes substantially reduce the likelihood of voting for these parties in CEE. In Western Europe, however, there is barely any difference in the probability of voting for a centre-right party if we compare people with the strongest and weakest anti-immigration attitudes.

Robustness checks

To assess the robustness of our findings, we have conducted several robustness checks. These checks can be found in online Appendix G. Here, we briefly outline the main outcomes.

First, we assessed how the results would differ if we used the standard technique of comparing far-right voters with the rest of the electorate. This reveals that the important nuances we highlighted are obfuscated in a conventional design. For instance, it shows that far-right voters have significantly stronger authoritarian sentiments, whereas our analysis revealed that this is not true if we compare them with centre-right voters. Another example is that the conventional design shows that far-right voters are less educated than the rest of the electorate, whereas we concluded that this is incorrect if we compare them with non-voters.

Second, to what extent are results influenced by the classification of parties and the inclusion or exclusion of countries? Since they are popular among a large portion of the population, PiS (Poland) and Fidesz (Hungary) are particularly important cases to consider. If we classify both parties as centre right, instead of far right, this leads to substantially different results with regard to the effect of trust in national politics: we find that in post-communist democracies far-right voters have less trust in national politics when compared with centre-right voters and left-wing voters (in line with H5). They are still more trustful than non-voters, although this difference becomes much smaller.

Our falsification of H5 for post-communist countries – far-right voters in CEE were more trustful – thus depends on the fact that we classified PiS and Fidesz as part of the far-right family. It is important to note that three parties we classified as far right were in power at the time of the surveys, namely PiS in Poland (since 2015), Fidesz in Hungary (since 2014) and Order and Justice in Lithuania (2012–16). Appendix G includes a country-by-country analysis of the effect of trust in national politics. Our robustness check suggests that the ‘protest voting’ explanation is context-dependent: when far-right parties are in government, their supporters are not politically dissatisfied, or at least not more so than voters of other parties. Two underlying mechanisms could be at work here: far-right voters become more trustful when a far-right party is in power, and other voters become less trustful.

Next, we have estimated our regression models for different subsets of the sample: we dropped countries one at a time to assess how sensitive the results are for outlying cases. These results show that our main findings are robust.

Finally, we have empirically assessed the contribution of each of the three explanatory approaches by evaluating the model fit of separate analyses (see Figure G2 in the online appendix). The results show that the full model, including all three approaches, has a significantly better model fit than any of the three separate models. This indicates that the three explanatory approaches complement each other, rather than substitute each other.

Conclusion and discussion

This article dissected citizens’ support for far-right parties by assessing three explanatory approaches – ‘cultural backlash’, ‘socioeconomic deprivation’ and ‘protest vote’. This three-fold distinction is common in the scholarship (Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren2018; Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Golder Reference Golder2016). Whereas previous research on the far right predominantly focused on explaining electoral support in Western Europe, we examine to what extent these explanations hold in both new and old democracies in Europe. The article's second main contribution is that it compared the far-right constituency with three other groups of citizens, including non-voters, rather than simply contrasting them with voters for all other parties.

We conclude that explanations for far-right support have parallels in mature and post-communist democracies. The far-right's constituency is particularly distinct from other citizens in terms of its anti-immigrant attitudes and political distrust of supranational governance. Nativist explanations clearly triumph. This confirms earlier studies showing that anti-immigration attitudes are one of the strongest factors for explaining electoral far-right support in Western Europe (Allen Reference Allen2017b; Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2017).

At the same time, our article adds to the existing literature by revealing important differences between post-communist and mature democracies when it comes to who chooses for the far right. Considering the ‘cultural backlash’ perspective, our findings show that in post-communist democracies, hostility towards immigration accounts to a lesser degree for electoral support for the far right. Its effects on far-right voting are considerably smaller (cf. Allen Reference Allen2017b; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2017).

Equally important, this article nuanced the paradigm of far-right supporters as people who are socioeconomically deprived (see Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2017). We conclude that they are not evidently the so-called ‘losers of globalization’ (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). This characterization only holds true when we compare far-right voters with centre-right voters. Regarding unemployment and perceived income, we conclude that the electorate of the far right does not differ from people who vote for traditional left-wing parties, in mature or post-communist democracies. Moreover, when compared with non-voters, far-right voters are more educated and have significantly higher perceived incomes (in both Western Europe and CEE).

To conclude, our more fine-grained distinction between groups paid off. This article has refined the debate about what characterizes far-right voters in Europe (Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2017). We followed the plea for more comparative research between Western and Central Eastern Europe (Bar-On Reference Bar-On and Rydgren2018) and illustrated the importance of specific group comparisons in relation to testing theories on electoral support for the far right. All voters for parties other than the far right are too often simply lumped together, while the abstainers are dropped from the research population (Allen Reference Allen2017a). Our analysis avoided generalizing in respect of mainstream voters by separating centre-right supporters from the left-wing voters. Our dissection furthermore underlines that it is remarkable that non-voters have hitherto been largely ignored in the extensive scholarship on the far right. Threatened socioeconomic status theories, which feature prominently in the literature, seem more appropriate to describe those who abstain from voting (cf. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018).

A possible avenue for future research is to achieve more in-depth understanding of the diverse groups of far-right voters. As Ivarsflaten (Reference Ivarsflaten2008) emphasized, for instance, uniformity in party identification and labelling is essential for comparative research. Especially when considering post-communist democracies, the lack of uniformity in far-right party selection is problematic. Categorization is time- and context-dependent because some mainstream parties radicalized (Bustikova Reference Bustikova and Rydgren2018; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2017) and similar parties can be treated differently. For example, Mudde (Reference Mudde and Mudde2017: 6) excluded UKIP and Alternative for Germany (as well as Fidesz and PiS) from the populist radical right family ‘because nativism is not a core feature of their party ideology’, whereas others included them. Future studies could investigate to what extent the electorates of such ‘borderline’ cases deviate from ‘genuine’ far-right parties. A limitation of our study is that we have not elaborated such dissections. In any case, what is considered ‘radical’ depends on the sociopolitical climate and differs by region (Bustikova Reference Bustikova and Minkenberg2015; Pirro Reference Pirro and Minkenberg2015).

A further limitation of our study is that the analytical distinctions drawn between the cultural backlash thesis, socioeconomic model and protest voting may be somewhat artificial. Labour-market concerns are related to attitudes towards immigrants; the higher one's socioeconomic status, the more favourable one's opinions about foreigners (Mayda Reference Mayda2006). Likewise, certain policy positions might enhance political distrust. Indeed, whether the theoretical framework includes distrust in supranational political institutions in the protest voting approach or in the ‘cultural backlash’ approach influences the explanatory power of each theoretical approach. We can assume that euroscepticism per se does not predispose voters to support the far right, but that it is linked to nativist beliefs (Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren2018) and irritation at the EU's promotion of minority rights and sociocultural liberalism (Stanley Reference Stanley, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017).

Finally, we focused on the socioeconomic background and attitudes of the European public, the so-called demand side of far-right parties. This study did not tell us much about the supply side. Most importantly, our study leaves open the important question of why far-right parties are more successful in some countries than in others. Or, for that matter, how parties are organized and how they succeed in advertising their agendas (Pytlas Reference Pytlas2016). The differences we revealed between far-right supporters and other segments of the European populations in both new and old democracies provide an important yet partial insight into the nature and electoral success of the far right.

Supplementary material

To view the supplementary material for this article please go to: https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.17.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this study were presented at the 2018 ECPR General Conference, the 2018 Dag van de Sociologie (annual conference of the Dutch and Flemish sociological associations) and at research meetings of the SILC and SCC research groups (VU Amsterdam). We would like to thank all participants for their helpful comments and suggestions. We particularly would like to thank Matthias Dilling, Harry Ganzeboom, Aat Liefbroer, Arieke Rijken and Sofia Lovegrove for their much-valued insights, feedback and proofreading. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers of Government and Opposition, whose feedback has improved this article considerably.